This module examines what cognitive development is, major theories about how it occurs, the roles of nature and nurture, whether it is continuous or discontinuous, and how research in the area is being used to improve education.

Learning Objectives

- Be able to identify and describe the main areas of cognitive development.

- Be able to describe major theories of cognitive development and what distinguishes them.

- Understand how nature and nurture work together to produce cognitive development.

- Understand why cognitive development is sometimes viewed as discontinuous and sometimes as continuous.

- Know some ways in which research on cognitive development is being used to improve education.

Introduction

By the time you reach adulthood you have learned a few things about how the world works. You know, for instance, that you can’t walk through walls or leap into the tops of trees. You know that although you cannot see your car keys they’ve got to be around here someplace. What’s more, you know that if you want to communicate complex ideas like ordering a triple-shot soy vanilla latte with chocolate sprinkles it’s better to use words with meanings attached to them rather than simply gesturing and grunting. People accumulate all this useful knowledge through the process of cognitive development, which involves a multitude of factors, both inherent and learned.

Cognitive development refers to the development of thinking across the lifespan. Defining thinking can be problematic, because no clear boundaries separate thinking from other mental activities. Thinking obviously involves the higher mental processes: problem solving, reasoning, creating, conceptualizing, categorizing, remembering, planning, and so on. However, thinking also involves other mental processes that seem more basic and at which even toddlers are skilled—such as perceiving objects and events in the environment, acting skillfully on objects to obtain goals, and understanding and producing language. Yet other areas of human development that involve thinking are not usually associated with cognitive development, because thinking isn’t a prominent feature of them—such as personality and temperament.

As the name suggests, cognitive development is about change. Children’s thinking changes in dramatic and surprising ways. Consider DeVries’s (1969) study of whether young children understand the difference between appearance and reality. To find out, she brought an unusually even-tempered cat named Maynard to a psychology laboratory and allowed the 3- to 6-year-old participants in the study to pet and play with him. DeVries then put a mask of a fierce dog on Maynard’s head, and asked the children what Maynard was. Despite all of the children having identified Maynard previously as a cat, now most 3-year-olds said that he was a dog and claimed that he had a dog’s bones and a dog’s stomach. In contrast, the 6-year-olds weren’t fooled; they had no doubt that Maynard remained a cat. Understanding how children’s thinking changes so dramatically in just a few years is one of the fascinating challenges in studying cognitive development.

There are several main types of theories of child development. Stage theories, such as Piaget’s stage theory, focus on whether children progress through qualitatively different stages of development. Sociocultural theories, such as that of Lev Vygotsky, emphasize how other people and the attitudes, values, and beliefs of the surrounding culture, influence children’s development. Information processing theories, such as that of David Klahr, examine the mental processes that produce thinking at any one time and the transition processes that lead to growth in that thinking.

At the heart of all of these theories, and indeed of all research on cognitive development, are two main questions: (1) How do nature and nurture interact to produce cognitive development? (2) Does cognitive development progress through qualitatively distinct stages? In the remainder of this module, we examine the answers that are emerging regarding these questions, as well as ways in which cognitive developmental research is being used to improve education.

Nature and Nurture

The most basic question about child development is how nature and nurture together shape development. Nature refers to our biological endowment, the genes we receive from our parents. Nurture refers to the environments, social as well as physical, that influence our development, everything from the womb in which we develop before birth to the homes in which we grow up, the schools we attend, and the many people with whom we interact.

The nature-nurture issue is often presented as an either-or question: Is our intelligence (for example) due to our genes or to the environments in which we live? In fact, however, every aspect of development is produced by the interaction of genes and environment. At the most basic level, without genes, there would be no child, and without an environment to provide nurture, there also would be no child.

The way in which nature and nurture work together can be seen in findings on visual development. Many people view vision as something that people either are born with or that is purely a matter of biological maturation, but it also depends on the right kind of experience at the right time. For example, development of depth perception, the ability to actively perceive the distance from oneself to objects in the environment, depends on seeing patterned light and having normal brain activity in response to the patterned light, in infancy (Held, 1993). If no patterned light is received, for example when a baby has severe cataracts or blindness that is not surgically corrected until later in development, depth perception remains abnormal even after the surgery.

Adding to the complexity of the nature-nurture interaction, children’s genes lead to their eliciting different treatment from other people, which influences their cognitive development. For example, infants’ physical attractiveness and temperament are influenced considerably by their genetic inheritance, but it is also the case that parents provide more sensitive and affectionate care to easygoing and attractive infants than to difficult and less attractive ones, which can contribute to the infants’ later cognitive development (Langlois et al., 1995; van den Boom & Hoeksma, 1994).

Also contributing to the complex interplay of nature and nurture is the role of children in shaping their own cognitive development. From the first days out of the womb, children actively choose to attend more to some things and less to others. For example, even 1-month-olds choose to look at their mother’s face more than at the faces of other women of the same age and general level of attractiveness (Bartrip, Morton, & de Schonen, 2001). Children’s contributions to their own cognitive development grow larger as they grow older (Scarr & McCartney, 1983). When children are young, their parents largely determine their experiences: whether they will attend day care, the children with whom they will have play dates, the books to which they have access, and so on. In contrast, older children and adolescents choose their environments to a larger degree. Their parents’ preferences largely determine how 5-year-olds spend time, but 15-year-olds’ own preferences largely determine when, if ever, they set foot in a library. Children’s choices often have large consequences. To cite one example, the more that children choose to read, the more that their reading improves in future years (Baker, Dreher, & Guthrie, 2000). Thus, the issue is not whether cognitive development is a product of nature or nurture; rather, the issue is how nature and nurture work together to produce cognitive development.

Does Cognitive Development Progress Through Distinct Stages?

Some aspects of the development of living organisms, such as the growth of the width of a pine tree, involve quantitative changes, with the tree getting a little wider each year. Other changes, such as the life cycle of a ladybug, involve qualitative changes, with the creature becoming a totally different type of entity after a transition than before (Figure 1). The existence of both gradual, quantitative changes and relatively sudden, qualitative changes in the world has led researchers who study cognitive development to ask whether changes in children’s thinking are gradual and continuous or sudden and discontinuous.

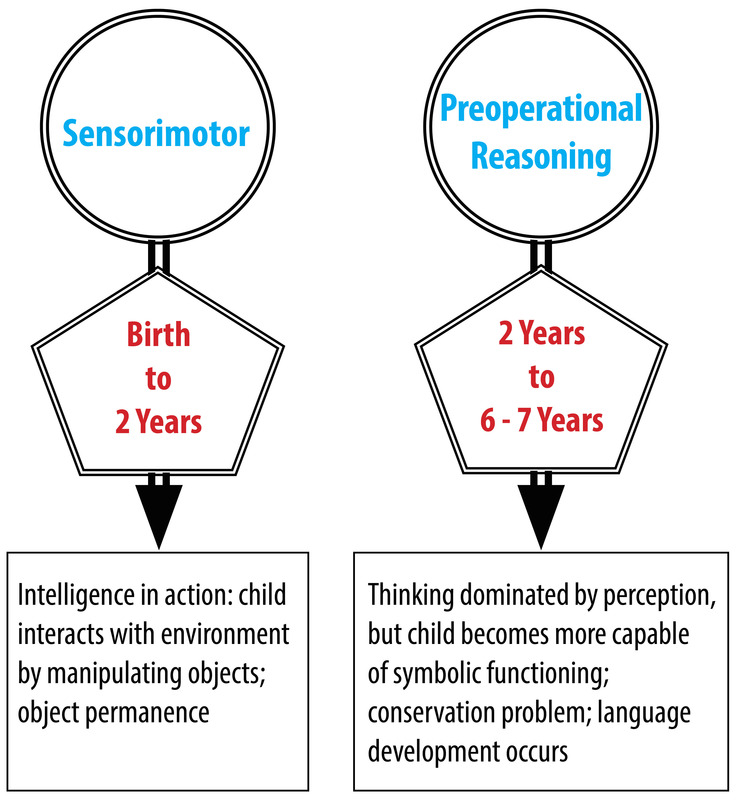

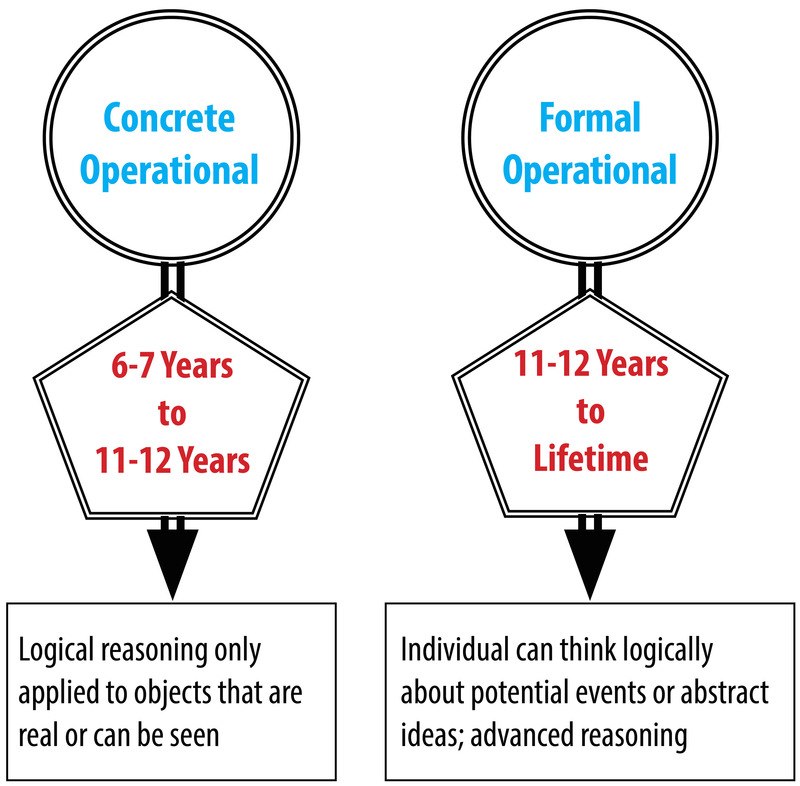

The great Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget proposed that children’s thinking progresses through a series of four discrete stages. By “stages,” he meant periods during which children reasoned similarly about many superficially different problems, with the stages occurring in a fixed order and the thinking within different stages differing in fundamental ways. The four stages that Piaget hypothesized were the sensorimotor stage (birth to 2 years), the preoperational reasoning stage (2 to 6 or 7 years), the concrete operational reasoning stage (6 or 7 to 11 or 12 years), and the formal operational reasoning stage (11 or 12 years and throughout the rest of life).

During the sensorimotor stage, children’s thinking is largely realized through their perceptions of the world and their physical interactions with it. Their mental representations are very limited. Consider Piaget’s object permanence task, which is one of his most famous problems. If an infant younger than 9 months of age is playing with a favorite toy, and another person removes the toy from view, for example by putting it under an opaque cover and not letting the infant immediately reach for it, the infant is very likely to make no effort to retrieve it and to show no emotional distress (Piaget, 1954). This is not due to their being uninterested in the toy or unable to reach for it; if the same toy is put under a clear cover, infants below 9 months readily retrieve it (Munakata, McClelland, Johnson, & Siegler, 1997). Instead, Piaget claimed that infants less than 9 months do not understand that objects continue to exist even when out of sight.

During the preoperational stage, according to Piaget, children can solve not only this simple problem (which they actually can solve after 9 months) but show a wide variety of other symbolic-representation capabilities, such as those involved in drawing and using language. However, such 2- to 7-year-olds tend to focus on a single dimension, even when solving problems would require them to consider multiple dimensions. This is evident in Piaget’s (1952) conservation problems. For example, if a glass of water is poured into a taller, thinner glass, children below age 7 generally say that there now is more water than before. Similarly, if a clay ball is reshaped into a long, thin sausage, they claim that there is now more clay, and if a row of coins is spread out, they claim that there are now more coins. In all cases, the children are focusing on one dimension, while ignoring the changes in other dimensions (for example, the greater width of the glass and the clay ball).

Children overcome this tendency to focus on a single dimension during the concrete operations stage, and think logically in most situations. However, according to Piaget, they still cannot think in systematic scientific ways, even when such thinking would be useful. Thus, if asked to find out which variables influence the period that a pendulum takes to complete its arc, and given weights that they can attach to strings in order to do experiments with the pendulum to find out, most children younger than age 12, perform biased experiments from which no conclusion can be drawn, and then conclude that whatever they originally believed is correct. For example, if a boy believed that weight was the only variable that mattered, he might put the heaviest weight on the shortest string and push it the hardest, and then conclude that just as he thought, weight is the only variable that matters (Inhelder & Piaget, 1958).

Finally, in the formal operations period, children attain the reasoning power of mature adults, which allows them to solve the pendulum problem and a wide range of other problems. However, this formal operations stage tends not to occur without exposure to formal education in scientific reasoning, and appears to be largely or completely absent from some societies that do not provide this type of education.

Although Piaget’s theory has been very influential, it has not gone unchallenged. Many more recent researchers have obtained findings indicating that cognitive development is considerably more continuous than Piaget claimed. For example, Diamond (1985) found that on the object permanence task described above, infants show earlier knowledge if the waiting period is shorter. At age 6 months, they retrieve the hidden object if the wait is no longer than 2 seconds; at 7 months, they retrieve it if the wait is no longer than 4 seconds; and so on. Even earlier, at 3 or 4 months, infants show surprise in the form of longer looking times if objects suddenly appear to vanish with no obvious cause (Baillargeon, 1987). Similarly, children’s specific experiences can greatly influence when developmental changes occur. Children of pottery makers in Mexican villages, for example, know that reshaping clay does not change the amount of clay at much younger ages than children who do not have similar experiences (Price-Williams, Gordon, & Ramirez, 1969).

So, is cognitive development fundamentally continuous or fundamentally discontinuous? A reasonable answer seems to be, “It depends on how you look at it and how often you look.” For example, under relatively facilitative circumstances, infants show early forms of object permanence by 3 or 4 months, and they gradually extend the range of times for which they can remember hidden objects as they grow older. However, on Piaget’s original object permanence task, infants do quite quickly change toward the end of their first year from not reaching for hidden toys to reaching for them, even after they’ve experienced a substantial delay before being allowed to reach. Thus, the debate between those who emphasize discontinuous, stage-like changes in cognitive development and those who emphasize gradual continuous changes remains a lively one.

Applications to Education

Understanding how children think and learn has proven useful for improving education. One example comes from the area of reading. Cognitive developmental research has shown that phonemic awareness—that is, awareness of the component sounds within words—is a crucial skill in learning to read. To measure awareness of the component sounds within words, researchers ask children to decide whether two words rhyme, to decide whether the words start with the same sound, to identify the component sounds within words, and to indicate what would be left if a given sound were removed from a word. Kindergartners’ performance on these tasks is the strongest predictor of reading achievement in third and fourth grade, even stronger than IQ or social class background (Nation, 2008). Moreover, teaching these skills to randomly chosen 4- and 5-year-olds results in their being better readers years later (National Reading Panel, 2000).

Another educational application of cognitive developmental research involves the area of mathematics. Even before they enter kindergarten, the mathematical knowledge of children from low-income backgrounds lags far behind that of children from more affluent backgrounds. Ramani and Siegler (2008) hypothesized that this difference is due to the children in middle- and upper-income families engaging more frequently in numerical activities, for example playing numerical board games such as Chutes and Ladders. Chutes and Ladders is a game with a number in each square; children start at the number one and spin a spinner or throw a dice to determine how far to move their token. Playing this game seemed likely to teach children about numbers, because in it, larger numbers are associated with greater values on a variety of dimensions. In particular, the higher the number that a child’s token reaches, the greater the distance the token will have traveled from the starting point, the greater the number of physical movements the child will have made in moving the token from one square to another, the greater the number of number-words the child will have said and heard, and the more time will have passed since the beginning of the game. These spatial, kinesthetic, verbal, and time-based cues provide a broad-based, multisensory foundation for knowledge of numerical magnitudes (the sizes of numbers), a type of knowledge that is closely related to mathematics achievement test scores (Booth & Siegler, 2006).

Playing this numerical board game for roughly 1 hour, distributed over a 2-week period, improved low-income children’s knowledge of numerical magnitudes, ability to read printed numbers, and skill at learning novel arithmetic problems. The gains lasted for months after the game-playing experience (Ramani & Siegler, 2008; Siegler & Ramani, 2009). An advantage of this type of educational intervention is that it has minimal if any cost—a parent could just draw a game on a piece of paper.

Understanding of cognitive development is advancing on many different fronts. One exciting area is linking changes in brain activity to changes in children’s thinking (Nelson et al., 2006). Although many people believe that brain maturation is something that occurs before birth, the brain actually continues to change in large ways for many years thereafter. For example, a part of the brain called the prefrontal cortex, which is located at the front of the brain and is particularly involved with planning and flexible problem solving, continues to develop throughout adolescence (Blakemore & Choudhury, 2006). Such new research domains, as well as enduring issues such as nature and nurture, continuity and discontinuity, and how to apply cognitive development research to education, insure that cognitive development will continue to be an exciting area of research in the coming years.

Conclusion

Research into cognitive development has shown us that minds don’t just form according to a uniform blueprint or innate intellect, but through a combination of influencing factors. For instance, if we want our kids to have a strong grasp of language we could concentrate on phonemic awareness early on. If we want them to be good at math and science we could engage them in numerical games and activities early on. Perhaps most importantly, we no longer think of brains as empty vessels waiting to be filled up with knowledge but as adaptable organs that develop all the way through early adulthood.

Discussion Questions

- Why are there different theories of cognitive development? Why don’t researchers agree on which theory is the right one?

- Do children’s natures differ, or do differences among children only reflect differences in their experiences?

- Do you see development as more continuous or more discontinuous?

- Can you think of ways other than those described in the module in which research on cognitive development could be used to improve education?

References

- Baillargeon, R. (1987). Object permanence in 3 1/2- and 4 1/2-month-old infants. Developmental Psychology, 23, 655–664.

- Baker, L., Dreher, M. J., & Guthrie, J. T., (Eds.). (2000). Engaging young readers: Promoting achievement and motivation. New York: Guilford.

- Bartrip, J., Morton, J., & De Schonen, S. (2001). Responses to mother’s face in 3-week to 5-month old infants. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 19, 219–232

- Blakemore, S.-J., & Choudhury, S. (2006). Development of the adolescent brain: Implications for executive function and social cognition. Journal of Child Psychiatry and Psychology, 47, 296–312.

- Booth, J. L., & Siegler, R. S. (2006). Developmental and individual differences in pure numerical estimation. Developmental Psychology, 41, 189–201.

- DeVries, R. (1969). Constancy of genetic identity in the years three to six. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 34, 127.

- Diamond, A. (1985). Development of the ability to use recall to guide action, as indicated by infants’ performance on AB. Child Development, 56, 868–883.

- Held, R. (1993). What can rates of development tell us about underlying mechanisms? In C. E. Granrud (Ed.), Visual perception and cognition in infancy (pp. 75–90). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

- Inhelder, B., & Piaget, J. (1958). The growth of logical thinking from childhood to adolescence. New York: Basic Books.

- Langlois, J. H., Ritter, J. M., Casey, R. J., & Sawin, D. B. (1995). Infant attractiveness predicts maternal behaviors and attitudes. Developmental Psychology, 31, 464–472.

- Munakata, Y., McClelland, J. L., Johnson, M. H., & Siegler, R. S. (1997). Rethinking infant knowledge: Toward an adaptive process account of successes and failures in object permanence tasks. Psychological Review, 104, 686 713.

- Nation, K. (2008). Learning to read words. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 61, 1121 1133.

- National Reading Panel (2000). Teaching children to read: An evidence-based assessment of the scientific research literature on reading and its implications for reading instruction. Washington, DC: National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

- Nelson, C. A., Thomas, K. M., & de Haan, M. (2006). Neural bases of cognitive development. In W. Damon & R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.) & D. Kuhn & R. S. Siegler (Vol. Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Volume 2: Cognition, perception, and language (6th ed., pp. 3–57). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Piaget, J. (1954). The construction of reality in the child. New York: BasicBooks.

- Piaget, J. (1952). The child’s concept of number. New York: W. W. Norton.

- Price-Williams, D. R., Gordon, W., & Ramirez, M. (1969). Skill and conservation: A study of pottery making children. Developmental Psychology, 1, 769.

- Ramani, G. B., & Siegler, R. S. (2008). Promoting broad and stable improvements in low-income children’s numerical knowledge through playing number board games. Child Development, 79, 375–394.

- Scarr, S., & McCartney, K. (1983). How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype-environment effects. Child Development, 54, 424–435.

- Siegler, R. S., & Ramani, G. B. (2009). Playing linear number board games—but not circular ones—improves low-income preschoolers’ numerical understanding. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101, 545–560.

- van den Boom, D. C., & Hoeksma, J. B. (1994). The effect of infant irritability on mother-infant interaction: A growth curve analysis. Developmental Psychology, 30, 581–590.

attribution

Cognitive Development in Childhood by Robert Siegler is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.