7 The Crucial Role and Responsibilities of the Mentoring Program Coordinator

Michael A. Christiansen and Don Busenbark

Abstract

Mentoring is a crucial part of personal and professional development in practically any environment, including higher education, industry, and private institutions, though the nature and methods of such mentoring may vary as much as the organizations themselves. Because institutions differ so much in their structures and needs, it is important that a dedicated program coordinator be assigned to define mentoring and spearhead the construction, implementation, assessment, and evaluation of any institutional mentoring program. This program coordinator should have enthusiasm for mentoring, effectively communicate program goals, and provide the training and resources necessary to implement an efficient mentoring model. Coordinators should also direct the assessment and evaluation process and make changes, as needed, to promote quality results. This chapter will explain this process in detail, outlining the characteristics and duties of the ideal mentoring program coordinator and some ideas for evaluating and supporting that individual. We will also detail the six phases of designing, executing, evaluating, funding, and sustaining a successful program, followed by suggestions for future research and ultimate conclusions.

Correspondence and questions about this chapter should be sent to the first author – M.christiansen@usu.edu

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank USU’s administration for all their mentoring support; in particular, Drs. Rich Etchberger, David Law, and James Taylor. We also thank all the supportive USU faculty and staff for their tireless dedication to mentoring and serving our students.

Introduction

Mentoring usually involves a mentor (a person who is providing direction) and a mentee (a protégé who is learning from the mentor). For the purposes of clarity, this chapter will focus on the mentoring of undergraduates, graduates, faculty, staff, employees, and other stakeholders across a wide spectrum of academic and nonacademic institutions or organizations. Thus, the term “mentoring program” may refer to any structure whose purpose is to guide and help such individuals along in their lives, responsibilities, or careers. As integral as the mentor/mentee relationship is to any mentoring program, a third component of mentoring will be specifically addressed in this chapter: the mentorship program’s organizational structure (Lunsford, 2016). In particular, this chapter’s narrative will focus on the central role of the mentoring program coordinator.

Foremost, it is important to address the characteristics and qualities of an ideal program coordinator. Enthusiasm, curiosity, effective listening, communication skills, and so on are some of the traits that adept program coordinators need. These attributes provide a catalyst for implementing a successful mentoring model. The main responsibility of the program coordinator, then, is to execute and maintain the mentoring program and resolve any issues that may arise while working with program stakeholders. For a detailed sample job description enumerating the ideal coordinator’s skills and characteristics, please see the Appendix to this chapter.

In this chapter, we will explain the role of the program coordinator in creating and shepherding a mentoring program. In particular, the sections that follow detail two processes that are critical for creating and maintaining a successful mentoring program: The Program Coordinator and The Six Phases of the Mentoring Program. We then follow with Future Research Considerations and Conclusions.

The Program Coordinator

In this section, we provide an overview of the program coordinator’s characteristics and duties and suggestions for the evaluation and support of the coordinator. (For a detailed sample job description enumerating the ideal coordinator’s skills and traits, please see the Appendix to this chapter.) In particular, this section covers the following: (a) The Characteristics and Qualities of an Ideal Mentoring Program Coordinator, (b) An Overview of the Program Coordinator’s Responsibilities, (c) Evaluating the Program Coordinator, and (d) Supporting the Program Coordinator.

The Characteristics and Qualities of an Ideal Mentoring Program Coordinator

In a paper on mentoring, Farah et al. (2020) listed various qualities of good mentors, such as energy and enthusiasm, scientific curiosity, effective listening, a mastery of one’s field, and frequent electronic or in-person communication with mentees. Though somewhat older, a separate mentoring book by a US tri-academy committee on science, engineering and public policy complementarily and succinctly affirmed that “good mentors . . . are good listeners, good observers, and good problem-solvers,” while also acknowledging that “there is no single formula for good mentoring” (Griffiths et al., 1997).

Mentoring may be difficult to perfectly define simply because it looks as infinitely varied and diverse as those who do it. We accordingly expect the sizes, makeups, needs, and goals of mentoring programs to be similarly varied, aligned to their settings and circumstances. Whatever the case, mentoring coordinators function primarily as the leaders of their programs. To the extent that good leaders should model the qualities and behaviors expected of those they lead, effective mentoring program coordinators should also be effective mentors themselves.

This does not necessarily mean that coordinators should actively mentor while supervising their programs. In fact, if coordinators’ concomitant duties preclude it, they might choose to opt out of mentoring while serving as coordinators (Donovan, 2010). Nevertheless, good coordinators will have past experience in both mentoring and leadership, thereby enabling them to guide and shepherd the mentors they supervise, as well as their program and its participants as a whole. It should follow that any descriptors in the literature of effective mentors and mentorship administrators might aptly apply to good program coordinators.

Coordinators’ education, training, and experience levels may be similarly varied but should equal or surpass those they supervise in their programs. Congruent with the aforementioned assertions of Farah et al. (2020), the personal and professional qualities of the ideal program coordinator would include energy and enthusiasm for mentoring, scientific curiosity, good listening abilities, strong written and oral communication skills, and a proficiency in using current electronic communication tools such as email, texting, and the direction of virtual meetings. Additionally, wherever one’s mentoring program includes goals of self-assessment and evaluation, the coordinator would also need an understanding of statistical analysis.

An Overview of the Program Coordinator’s Responsibilities

Mentoring program coordinators have several duties, the ultimate purpose of which is to guide their programs through six key phases, to be discussed later on in this chapter. At the broadest level, these duties include establishing or maintaining the mentoring program structure, training its participants, and working with them to refine, improve, and carry out program goals. Duties also include assessing and evaluating the program’s effectiveness, making necessary adjustments, and then reassessing and reevaluating the program in a continual reiterative feedback loop to help refine and improve the program.

For organizations that lack a well-structured mentoring program, the coordinator creates and works with a mentoring committee to formalize mentoring definitions, parameters, rules, and procedures, including a process for matching or assigning mentors to mentees. In settings where a defined structure already exists, the program coordinator works with committee members to ensure that procedures are followed and, as needed, helps to update and adjust those procedures.

To accomplish this, program coordinators should meet regularly with their mentoring committee, whose team members may include mentoring supervisors, mentors, and possibly even some mentees. According to the company, organization, or institution’s mentoring needs and size, the number and committee makeup understandably vary.

In academic settings where participant survey data (i.e., mentor and/or mentee feedback) are gathered in order to assess and evaluate a program’s effectiveness—especially if there exists an intent to eventually publish their findings—coordinators take the lead in authoring and submitting an institutional review board (IRB) proposal, before implementing the program. (For more information on this, please see Chapter 14, “The Mentoring Program as a Research Project.”) In nonacademic settings, this process might instead involve human resource specialists. In either case, the coordinator may choose to include committee members in this proposal-authoring process. Once approved, the coordinator then ensures that committee members and mentors are trained in following its authorized procedures.

Wherever an organization is large enough to require additional mentoring administrators, such as managers who oversee the activities of individual mentors, the program coordinator would supervise those managers and meet regularly with them to train mentors and assess and evaluate their performance, answer questions, and adapt program specifications to fit their particular needs. The program coordinator must work closely with institutional and organizational leaders to secure continual program support, to ensure that the program successfully meets its goals, and to recalibrate the program as determined through assessment and evaluation. (For greater detail on working with institutional leaders, please refer to Chapter 6, “The Mentoring Context: Securing Institutional Support and Organizational Alignment.”)

As mentioned, depending on program size and specifications, the coordinator also helps to assess and evaluate the program as participants’ surveys and other data are collected. If sufficient resources are available, a separate team or committee member may be hired or assigned to gather, collate, analyze, and track these data. The coordinator would then work with that individual or team in the assessment and evaluation process.

Program coordinators might also work as mentors themselves, thereby leading other mentors by example. However, if their duties are too numerous to make this workable, coordinators may opt out of serving as mentors (Donovan, 2010). Additionally, wherever an organization or institution has higher managers or administrators who supervise the program, the coordinators would also serve as a communication relay hub between upper administration and the program managers, committee members, and mentors.

Evaluating the Program Coordinator

That we are aware, there are no literature or research reports that specifically address the evaluation of mentoring program coordinators. However, because evaluation is a key component of any program’s success, it is expected that the coordinator should also be evaluated. In fact, Zwikael and Meredith (2019) argue that merely evaluating the program is somewhat limiting, as it does not provide a complete picture of the program’s actual success or failure. Thus, it is essential that the coordinator should also be evaluated, along with the program.

How will the coordinator’s supervisor know if the coordinator is successful? Before the coordinator starts implementing the program, expectations should be clearly defined by the administration. These expectations should provide the coordinator with precise goals and directions, which in turn will clearly define what will be evaluated. The program coordinator should accordingly understand these goals, the job requirements, the project timeline, and available funding prior to carrying out program duties.

Institutional administration or management should also indicate whom the coordinator will report to and how often. In addition, this report should include information regarding the status of the program’s implementation, how many participants are involved, the trainings administered, which issues have been identified and resolved, which data have been collected, and funding needs. These data and reports will allow the program coordinator to adjust the program as needed and enable stakeholders to better understand the impact of mentoring on organizational culture.

Understandably, the success or failure of the mentoring program depends greatly on the program coordinator. The metrics by which this success is determined should accordingly be defined by the stakeholders and upper management. Questions to be considered in determining program success should mirror the institution’s objectives for the program. Such questions might include: Has the program met its designated goals? Has the coordinator met the established timeline? How many students, faculty, or employees are involved in the program? Are there concrete goals for program growth? Has the program coordinator met these goals? Has the coordinator stayed within budget? How has the program been perceived?

Zwikael and Meredith (2019) suggest that any evaluation of a program should be multidimensional, with many facets being used to determine its level of success. They further state that “project success can be different from the successful performance of its leaders” (p. 1747). Thus, a program’s inability to reach its objectives does not always indicate that a coordinator has failed. However, ultimately, the coordinator is the one who bears the responsibility of collecting enough data to provide administrators with the information needed to fairly and accurately assess the coordinator’s performance.

As the literature is limited in its scope with respect to mentoring programs, we recommend that more research into mentoring programs be conducted, with specific consideration of the role, responsibilities, and evaluation of the mentoring program coordinator.

Supporting the Program Coordinator

Ultimately, the program must have support from top administration. As one source explains, “It is difficult for a midlevel administrator to drive a program if the staff members are aware that he or she is not supported at the most senior levels (Ehrich et al., 2004, p. 535). Ideally, a successful mentoring program will be spearheaded or supported by top administrators, who hire or assign coordinators and committee members under their purview. If the program itself germinates from the organization’s midlevel management or staff, then it will have to be successfully pitched to upper administrators to obtain sufficient buy-in. Otherwise, the program may fail before or shortly after launch.

Support structures are not limited solely to buy-in from top managers and may vary according to institutional resources, program objectives, and the extent of administrative backing. Such structures may include the number of support personnel (i.e., staff or assistants), the degree to which the program is marketed, the amount of equipment available (office space, computers, and other materials), training and public recognition, and budget. Of note, depending on program specifics, the budget may need to cover things like financial compensation of mentors, travel costs, and reimbursement for conference attendance and presentations. As necessary, program coordinators may seek out additional funding, such as grants or institutional and foundation backing.

One separate piece of mentoring success that often gets overlooked is the institutional recognition of mentors and other program participants. Such recognition can range from something as simple as listing a “mentor of the month” on a company newsletter or bulletin to creating mentoring awards or certificates, badge programs, or even financial incentives for outstanding mentors. Whatever the case, this area should be considered. In fact, one source on mentoring programs for KL2 scholars affirms that “creating a culture that publicly expresses gratitude for mentoring is also seen as a means of providing mentor support” (Silet et al., 2010). The fact is, most people love being recognized for their hard work and dedicated contributions.

As one more consideration, Putsche et al. (2008) affirm that the program coordinator should contemplate institutionalizing the program in order to ensure its long-term success, which we will discuss in detail later on. As with any structure, the stronger the program’s foundation, the better its results will be, and positive results can contribute significantly toward enhancing program support. It is imperative, then, that from the program’s inception, the coordinator and mentoring team properly design the program, along with its objectives, means of assessment and evaluation, and marketing strategies. These aspects will be addressed later under Phase 3: Designing the Program.

The Six Phases of the Mentoring Program

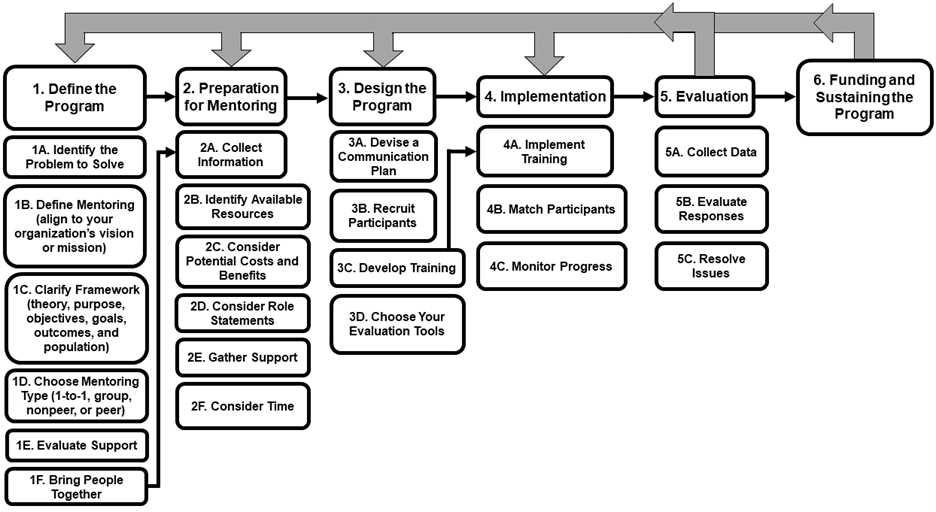

Koczka (2017) and Lunsford (2016) separately but complementarily affirm that the program coordinator’s role is to organize and manage different phases in the mentoring program’s development and execution. We have based Figure 7.1 below on Lunsford’s work but have also adapted it in several ways, including the addition of a sixth phase (Funding and Sustaining the Program) beyond Lunsford’s original five. These phases, boxed from left to right in Figure 7.1 and explored hereafter in detail, are as follows:

- Phase 1: Define the Program

- Phase 2: Preparation for Mentoring

- Phase 3: Design the Program

- Phase 4: Implementation

- Phase 5: Evaluation

- Phase 6: Funding and Sustaining the Program

Phases 5 and 6 (upper-right boxes in Figure 7.1)—the Evaluation and Funding and Sustaining the Program phases—should be considered and integrated throughout the development and execution process for every previous phase, from start to finish and everywhere in-between. This explains why Phases 5 and 6 are connected by arrows flowing back into each of the preceding phases in Figure 7.1. In other words, the implementation of Phases 5 and 6 is not a linear process because evaluation, funding, and sustainability impact each of the prior phases.

Figure 7.1

The Six Phases of Mentoring Program Design, Execution, Evaluation, Funding, and Sustainment

For example, if the type of mentoring chosen during Phase 1 were one-on-one mentoring, how would this impact the type of data needed during the formative and summative evaluations obliged by Phase 5? Another example may be, how might the type of data collected vary if the program focused on second-year staff members? Junior management? Midcareer faculty? Again, Phases 5 and 6 should be considered throughout the entire program design and implementation process, from beginning to end.

Continuing to Phase 6, the life length, sustainability, and longevity of any mentoring program depend greatly upon the resources supporting it, which in addition to funding, also include any available infrastructure, personnel, physical space, equipment, and invested time required for implementation. Thus, in order for a program to last, its design must consider each of these variables from its outset by scrutinizing the funding, infrastructure, and personnel availabilities that actually exist. A coordinator might otherwise design a program that looks perfect on paper but fails in practice due to a lack of resources needed to carry it out. It is hopefully apparent, then, why the ubiquity and feedback loop of Phases 5 and 6 are essential in the evolution of each preceding phase. We now examine these phases in detail.

Phase 1: Define the Program

Before starting Phase 1, coordinators should become familiar with peer-reviewed research on mentoring and with their specific institutional needs and resources (Benabou & Benabou, 2000). They can then begin assembling a group of people who will constitute the previously mentioned mentoring committee. This committee will help to prepare, design, implement, and evaluate the mentoring program. Allen et al. (2006) indicate that commitment is a key factor in the effectiveness of any mentoring program. Thus, this team should include people who are sufficiently experienced and invested in the program’s success because they will be instrumental in supporting the coordinator and in helping to maintain the program’s fidelity. Naturally, this group’s roster will vary over time as needs and personnel availabilities change.

Once chosen, this group moves on to Phase 1 together, working to define the program itself (Figure 7.1, upper-leftmost box). This process begins by identifying the problem or problems (Figure 7.1, Box 1A) that the program will address. The problems chosen may vary considerably, depending on the institution or organization’s circumstance. For example, in academic settings, program goals might include increasing student retention or graduation rates, improving morale among graduate students, augmenting the number of peer-reviewed papers written by faculty, or expanding the rate of junior faculty who obtain tenure. In other settings, goals might include decreasing staff turnover, increasing employee promotion rates, or enhancing staff or employee proficiency. Whatever the case, the specifics of the problem to be addressed by the program must be identified during Phase 1. In other words, the committee should begin by answering the question, “What problem are we trying to solve, or what needs are we trying to address with this program?”

During Phase 1, the term “mentoring” (Box 1B) must also be defined in a way that is actionable and aligns with the vision, mission, and values of the institution or organization. This is sometimes harder than one might presume. For instance, in one review by Jacobi (1991), 19 different definitions of mentoring were found. Some years later, Crisp and Cruz (2009) increased that number to more than 50 definitions. Whatever ambiguity may exist, for the sake of program functionality, an operational definition should be researched and chosen by the coordinator and committee members in a way that corresponds to the institution or organization’s goals and needs. As Koczka explains, “In this initial phase, the program coordinator will define the mentoring within the context of the organization and identify how it is different from any other types of personal development” (Koczka, 2017, p. 249). For more information on creating an operational definition, please see Chapter 1, “Mentoring Origins and Evolution.”

The coordinator and committee now move forward with clarifying the program’s framework (Box 1C). This begins by choosing a mentoring theory that will help frame thinking about the program (Lunsford, 2016). Dawson (2014) proposes that doing so can “clarify communications about mentoring” for those involved in the program and can “reveal implicit assumptions or omissions in the design of mentoring models” (p. 138). All who work as coordinators or mentors should understand how this theory will impact them and what it will look like in the context of their organization. Naturally, the theory chosen to underpin the program should complement the institution or organization’s vision, mission, culture, and values. For more on this, please see Chapter 2, “Articulating a Theoretical Framework of Mentoring.”

The establishment of a mentoring theory constitutes one part of the “Clarify Framework” step seen in Box 1C of Figure 7.1. However, this step also includes defining the program’s purpose, objectives, goals, and outcomes. Of this, Crockett and Smink (1991) explain, “Every program must have an overall purpose or a set of predetermined goals in order to achieve desired results” (p. 23). According to Sanchez (2018), these goals should be clearly articulated because clear outlines and objectives contribute to an effective program and provide opportunities for later assessments and adjustments. Thus, program goals and objectives should be determined early in development to help drive decisions that will impact the eventual outcome. For further details, please see Chapter 8, “Outlining the Goals, Objectives, and Outcomes of the Mentoring Program.”

In addition to setting purpose, objectives, goals, and outcomes, the framework clarification stage (Box 1C) also includes identifying the program’s target population, this population’s needs, and how to structure the program to best address those needs (Crocket & Smink, 1991). This “needs assessment” step should help identify the mentee population of focus for the problem and should include information to be used to identify faculty, staff, employees, or others to potentially recruit as mentors. This process feeds synergistically backward to further refine and develop the program’s purpose, objectives, and goals. In practice, for instance, one might ask, “Based on the problem chosen in Box 1A, what population is this program designed to help?” This question’s answer can reshape program goals and objectives, which ultimately direct each subsequent stage of its design and execution. In effect, then, Phase 1 helps cement the foundation upon which the entire program will rest, so it must be done with painstaking care. For more on this subject, please see Chapter 5, “Needs Assessment and Data Analytics: Understanding your Constituencies.”

Now in Box 1D, the coordinator and mentoring committee choose the type (or types) of mentoring their program requires (Koczka, 2017). For instance, are the problems addressed by the program (Box 1A), its mentoring definition (Box 1B), and its framework (Box 1C) best solved through one-on-one mentoring or mentoring in a group? Do the program’s needs call for peer-to-peer mentoring (i.e., a more experienced coworker mentoring a less experienced one at a similar level)? Or does it call for nonpeer mentoring, such as a professor mentoring a student? As one might imagine, the steps shown in Boxes 1A through 1D are quite interconnected and might be developed cyclically together, despite being depicted linearly in Figure 7.1. For more information on mentoring types, please consult Chapter 3, “Mentoring Relationships Typology,” and Chapter 27, “Developmental Networks.”

According to Ehrich et al. (2004), adequate support and appropriate alignment to goals are needed to ensure the success of any mentoring program. This advances our journey to the next stage of Phase 1, which is to evaluate support (Box 1E) by listing and quantifying the organizational resources available. These include tangibles such as funding, infrastructure, personnel, physical space, and equipment, as well as more abstract (but still crucial) things like administrative support and enthusiasm, time requirements for participants (mentors, mentees, committee members, and administrators), and community interest, both within and outside the organization (that is, of both internal and external stakeholders). This appeal to available support and resources is a recurring theme throughout Figure 7.1, reappearing in various forms within Boxes 2B and 2D and Phase 6, feeding back into each preceding phase and step. Thus, while carrying out this “evaluating support” process or implementing the program later on, the mentoring committee might determine that its program design and goals need readjusting in order to fit within the real-world limits of its available resources.

Phase 1 nears completion as the coordinator and committee move to Box 1F: bringing people together. This step involves gathering additional stakeholders who are not on the mentoring committee, such as other administrators, faculty, staff, employees, and student representatives. This gathering, which may occur in-person or virtually and over one or possibly multiple meetings, dovetails naturally into Phase 2, as indicated by the arrow connecting Box 1F to Box 2A in Figure 7.1.

Phase 2: Preparation for Mentoring

The assembly of stakeholders from outside the mentoring committee initiates Phase 2: Preparation for Mentoring (Figure 7.1, upper-left box). According to Koczka (2017), to begin preparing any mentoring program, the coordinator needs to collect information (Figure 7.1, Box 2A) on the readiness of the institution, company, or organization, the benefits of mentoring, and any barriers to implementation. Although much of this is done during Phase 1 by the coordinator and mentoring committee, Phase 2 begins the collection of information from people who are outside the committee, who then give feedback that might include identifying additional resources (Box 2B) that were previously unknown by the committee and its members. Other discussion questions may be asked, such as: Who are the participants? Where will we find mentors? Who are our mentees? Feedback obtained during Phase 2, which may occur over multiple meetings and additional communications, will almost invariably prompt a need to readjust the developing program design from Phase 1.

Broadly speaking, in assessing the resources needed for the implementation of any mentoring program, the coordinator needs to include a cost/benefit analysis (Box 2C), which might be more accurately done based on information gathered during this larger meeting of people from inside and outside the mentoring committee. Koczka (2017) suggests that both “costs and returns” should be determined. For instance, how much will the program cost on the front end? What will be the potential returns on the back end? In performing this assessment, the cost of materials and activities for recruiting mentees, and possibly mentors, should be weighed against the potential benefits of achieving the program’s goals.

As Box 2D indicates, in academic settings, interested faculty might worry about how to balance their potential work as mentors with other responsibilities in their role statements or professional contracts. In fact, potential mentors at any organization might have similar or analogous concerns. Above all, mentoring should not be compulsory (Allen et al., 2006). Instead, role statements and employment agreements for the program coordinator, mentors, mentees, and anyone else involved, should be clearly defined (Dawson, 2014; Sanchez, 2018), which requires effective communication of the organizational values and culture that are being cultivated within the program (Benabou & Benabou, 2000). These concerns should be discussed during this key meeting with stakeholders from inside and outside the mentoring committee, using genuine empathy and consideration for role statement responsibilities and time limitations.

The meeting, meetings, or other communications carried out during Phase 2 also provide a great opportunity to gather support (Box 2E) from the administration, faculty, resource staff, or other personnel because doing so is essential for program longevity and success (Sanchez, 2018). The program coordinator should accordingly use this time to communicate the benefits of mentoring to stakeholders, recruit additional mentors, and advocate for administrative and personnel support. Additionally, the discussions should also convey why the target population was chosen for help and how the mentoring program will achieve that goal. For greater detail on working with institutional leaders, please refer to Chapter 6, “The Mentoring Context: Securing Institutional Support and Organizational Alignment.”

Lastly, program coordinators need to consider the time required (Box 2F) to implement mentoring so that the program will progress and encounter fewer problems (Crockett & Smink, 1991). Time is needed for training faculty in the mentoring program, for effectively managing it, for evaluating the program, and addressing issues or concerns. In academic settings, program coordinators manage time and should be “cognizant of the need to strike a balance among teaching, research, and service responsibilities for each faculty colleague” (Hackmann & Wanat, 2008). Program coordinators should be realistic in their goals and understand that implementation usually takes more time than initially allotted (Crockett & Smink, 1991; Sanchez, 2018).

In summary, Phases 1 and 2 are a cyclical process of designing the mentoring program, gathering information and feedback, and then recalibrating the original design. Phase 1 focuses primarily on input from the mentoring committee, while Phase 2 focuses on input from stakeholders outside that committee. Understandably, Phases 1 and 2 have more written steps than the later phases because they form the foundation upon which the rest of the program is built.

Phase 3: Design the Program

In Phase 3, the committee operates under the coordinator’s direction to design their mentoring program, built on the results obtained through the refining process of Phases 1 and 2. For those at colleges and universities utilizing faculty or staff, it is recommended that the coordinator select a formal or semiformal mentoring program that is decentralized. Such programs allow for matching and monitoring while also providing a means for record-keeping and evaluation. A decentralized program provides for decision-making by the various stakeholders and enables individual variations based on institutional resources and needs (Benabou & Benabou, 2000). In one paper, Allen et al. (2006) suggest that formal mentoring programs that mimic a more informal mentoring relationship might help to improve the program’s effectiveness.

For Phase 3, the first recommended step in program design is to develop a communication plan (Figure 7.1, Box 3A): a strategy for how to effectively market and convey information about the program to the community and population being recruited. If that group is properly identified during Phase 1 (Box 1C) and Phase 2 (Box 2E), then constructing an effective communication plan becomes much easier. Specifics will vary according to organization and need. For example, if the entire program were intraorganizational, then its target population would be completely in-house. Thus, the communication plan might be something as simple as setting up a workgroup email, online discussion board, recurring meeting (either in-person or virtual), regular newsletter, company blog, institutional website, bulletin board with flyers, or other electronic or hardcopy means of spreading news about the program.

Contrastingly, if the target population and community lie beyond the physical or virtual walls of the institution or organization, then farther-reaching communication methods are likely necessary. Such methods might include social media marketing, the dissemination of electronic or hardcopy flyers, individualized texts or phone calls, booths at community events, or other advertisements in key geographic areas. If the institution has a marketing specialist (identified as a resource in steps 1E and 2E), then it might be appropriate to ask that specialist for assistance. Whatever the case, the purpose of devising a communication plan is ultimately twofold: first, to effectively market the program, and second, to devise a seamless way for all participants (managers, mentors, and mentees) to communicate with each other once the program is implemented.

This dovetails seamlessly into the next step of Phase 3: recruiting participants (Box 3B). This recruitment extends to two groups: potential mentees (the target beneficiaries of the program) and potential mentors. At this stage, mentee recruitment involves simply enacting the now-established marketing component of the communication plan. For recruiting mentors—who will all be employees, faculty, staff, or volunteers from within the organization itself—groundwork laid during steps 1E and 2E should have helped identify supportive individuals who are both willing and qualified. Thus, at this stage, the program coordinator reaches out to those potential mentors, either in a group setting (such as a staff, faculty, or team meeting) or one-on-one, according to appropriateness and need.

During this process, the coordinator should actively seek accomplished faculty, senior staff, administrators, or other employees who have the appropriate characteristics and qualities needed to contribute to an effective mentoring program (McCann et al., 2010). Thus, program coordinators should look for and recruit individuals to the program in order to establish a pool of mentors in advance prior to implementation (Ganser, 1995). It is not enough to just recruit mentors to participate. In academic settings, for instance, program coordinators, supervisors, and administrators “must understand all faculty members’ strengths and weaknesses, working with them to ‘maximize their contributions to the department’” (Hackmann & Wanat, 2008). For programs that are carried out across multiple locations, this may involve having a different supervisor at each site in order to help the program coordinator and upper administration better understand the individual mentors, as well as how to most effectively utilize those mentors within the program.

Although recruiting qualified mentors is indispensable, Allen et al. (2006) suggest that programs allowing for voluntary participation had greater success than those that mandated participation. Thus, mentoring should not be compulsory. Instead, the program coordinator might consider working with upper administrators to devise awards, recognitions, or other forms of positive incentives to honor participants. If possible (see Box 2D), the addition of a mentoring component to role statements, employee agreements, or staff contracts might also be considered. As mentioned earlier, “Creating a culture that publicly expresses gratitude for mentoring is also seen as a means of providing mentor support” (Silet et al., 2010).

Once mentors are recruited, program development shifts to the next step: developing training (Box 3C). Training development is imperative and gets spearheaded by the program coordinator during dedicated mentoring committee meetings. In these sessions, the committee designs a repository of step-by-step protocols to guide mentors and mentees so they can succeed in their respective roles and duties. For example, the committee might consider writing an individual mentor guidebook and mentee guidebook, which program participants could readily access and use. These guidebooks would provide clear expectations and answers to common questions, such as: How often should mentors and mentees meet? What is the expected duration of these meetings? What help should the mentor provide? What should the mentor avoid? What questions or subjects should the mentors and mentees discuss during their meetings?

Training materials or sessions should also contain a guide or list of available resources for the mentor to share with mentees. These would include explanations or lists of accessible human resources, counseling, or other supportive materials that might be useful or pertinent to mentees. Creating such lists or guides before implementing the program will help mentors to better understand their role. Allen et al. (2006) contend that program understanding is a key variable for its effectiveness. Additionally, if web design expertise is available, a dedicated company or institutional website on mentoring can be made, serving as a readily accessible repository for these training materials. The training program might also include the creation of an oral training presentation (discussed later on) to be carried out by the program coordinator or another committee member during the training process. For additional information, please consult Chapter 10, “Preparing the Effective Mentor,” and Chapter 11, “Preparing the Effective Mentee.”

With a training program and materials developed, the coordinator and committee should recognize the need to evaluate the program’s effectiveness and address any issues that may arise during its implementation. This naturally requires finding or designing evaluation tools (Box 3D), which should be based on the ease of collecting the type of information needed, all built on the framework established during Box 1C of Phase 1.

Of note, without a system of assessment and evaluation, one can never know if the mentoring program is achieving its goals. This process, therefore, requires obtaining data (i.e., mentor and/or mentee feedback) to gauge the perceptions of mentors and mentees. According to Allen et al. (2006), “Perceptions of program effectiveness likely play a large role in determining whether or not individuals will continue in the program, if others will sign up for the program, and ultimately whether or not the program will continue” (p. 126). For any concerned about the process, Chapter 13 of this book (“Monitoring and Supporting the Mentoring Program and Mentoring Relationship Through Formative and Summative Evaluation”) encouragingly explains that the evaluation process does not have to be complicated but does require obtaining information about program participants and their sense of the mentoring procedure and results. Additionally, assessments and evaluations should include both formative and summative tools and may require comparing participants with nonparticipant control groups.

Of note, there is a technical difference between assessment and evaluation. In a mentoring context, Chapter 13 explains assessment as involving direct, self-reported feedback from mentoring participants about their experiences, while evaluation requires a judgment about whether or not the program is accomplishing its goals. Thus, the obtaining of data is assessment, while analyzing and judging those data to determine the program’s effectiveness is evaluation.

The specific assessment tools used would naturally depend on program goals. For more easily measured outcomes, such as increasing the number of peer-reviewed papers written by faculty, the assessment could simply involve comparing the publication numbers of those who were mentored with those who were not; or comparing the publication numbers before and after being mentored.

Separately, obtaining data about participants’ perception of the mentoring process, outcomes, and their self-reported experiences would invariably require some type of survey instrument, which could be administered electronically online or on paper. Anonymity might be necessary to ensure unbiased feedback, but the choice of tools, metrics, and questions ultimately hinges on program goals and objectives. It is understandably crucial to collaboratively establish and design the program goals and assessment tools during Phase 1, prior to implementation.

Congruently, the program coordinator should monitor the mentoring program feedback and relationships to ensure faithful implementation, as well as to intervene when needed (Sanchez, 2018). For example, in one mentoring program with which the authors are quite familiar, each mentor and mentee is asked to fill out a short monthly survey online and report experiences with the program from the past month. The program coordinator and one other committee member then read the survey results and look for any concerning feedback, such as reports of mentors and mentees not meeting, feelings of dissatisfaction with the program, or potentially questionable behavior. If any issues arise, the coordinator reaches out individually to those involved or affected to help resolve these problems. If more significant issues occur, such as unethical conduct, then the coordinator reaches out to higher administration. The evaluation process will be discussed more deeply in our later coverage of Phase 5.

Phase 4: Implementation

As Box 4A indicates, Phase 4 launches by the implementation of the training developed during Phase 3. This training includes at least two components: the guidebooks or other written materials discussed earlier and an oral presentation for mentors given by the program coordinator or designated committee member. This presentation can be done in a group setting (such as a faculty, staff, or team meeting) or through dedicated sessions with specific participants. Ideally, it should be video-recorded and made accessible online for all mentors.

The next step is for the coordinator and committee to create a list of mentor-mentee assignments; in effect, to match and assign mentors with mentees (Box 4B). Ganser (1995) indicates that various factors—such as mentor and mentee needs, degree or vocational interests, physical locations, personalities, aptitudes, and dispositions—should all be considered when matching mentors with mentees to reduce problems that might occur later. Once the committee has made their matching list, the coordinator should reach out individually to the mentors to inform them of their mentee assignments and ask if any changes need to be made. If mentors object to any of their assigned mentees, then the coordinator and committee can discuss (perhaps through a quick group email) changing the assignment. Once the mentor-mentee matching list is finalized, the coordinator reaches out to give the mentors a list of each of their mentees, pertinent information such as mentees’ full names and contact info, and basic instructions on what the mentors are supposed to do next. This communication might best be done with a boilerplate email template, whose details can be adjusted to fit each mentor’s assignments. Specifics on what the mentors are supposed to do next, which should most especially include setting up their first meetings with mentees, should complement the knowledge presented during the earlier training presentation (Box 4A).

At last, the mentoring program begins its implementation, as mentors meet with mentees and carry out the types of activities covered in their training. As this implementation unfolds, the program coordinator and possibly other committee members monitor the program’s progress (Box 4C) by regularly reading feedback obtained through the evaluation tools (monthly surveys or other reporting instruments) that were developed and discussed under Box 3D above. Logically, the mentoring program is not static but is instead a dynamic, evolving entity that gets readjusted by the analysis of these evaluations. In this sense, every participant helps to shape the program’s current and future mentoring practices (Crockett & Smink, 1991; Bell & Treleaven, 2011).

Phase 5: Evaluation

Evaluation—both formative and summative—of any program is critical, not just to determine its effectiveness but also to identify areas that need improvement (McCann et al., 2010, p. 95). As suggested earlier, evaluations should be provided in the form of surveys, reflections, and interviews. Surveys conducted monthly will help to ensure the fidelity of the program and allow for solving issues in a timely manner. Reflections and interviews can provide information on anecdotal experiences to inform change. Clear outlines and objectives foster an effective program and give opportunities for assessments and adjustments (Sanchez, 2018).

Although mentoring should ideally be a positive experience, it does involve people working with people. Thus, negative issues sometimes arise and should be addressed by the program coordinator (Bell & Treleaven, 2011). Concerns such as personality clashes, unresponsive students, inadequate mentors, and loss of interest are issues that the program coordinator must work out. A successful program deals with these issues through cooperation and collaboration between all participants involved in mentoring (Klinge, 2015). Mentoring can be difficult for some participants, so a procedure for ending a mentoring relationship should be included in the program design (Dawson, 2014). In fact, McCann et al. (2010) recommend that a process be in place to alert the program coordinator when a mentoring relationship is not functioning effectively.

Phase 6: Funding and Sustaining the Program

As mentioned earlier, Putsche et al. (2008) affirm that the program coordinator should consider institutionalizing the program in order to facilitate and ensure its long-term success. In other words, funding and sustainability (Phase 6, shown in the upper-rightmost box of Figure 7.1) are critical for the ongoing existence of all prior phases—and hence, for the mentoring program itself. This is why Phase 6 feeds back into all the other phases in Figure 7.1. Hence, in order to ensure the program’s continued existence, coordinators and committee members should consider the program’s longevity from the outset of Phase 1. This will likely involve the coordinator and committee preparing a budget, securing organizational buy-in, and obtaining other financial support, such as grants or institutional or foundational backing.

Future Research Considerations

Although program coordinators are integral to implementing an effective mentoring program, there exists very little research on program coordinators specifically. Instead, most research literature focuses on the experiences of the mentee and, to some extent, of the mentor, but little on the coordinator, program director, or comparable administrators. Koczka (2017) recommends that more research is needed on the reflections and observations of program coordinators. Such research would provide insight into how to develop and improve a mentoring program from the perspective of program coordinators/directors, as well as how to identify best practices in operating a successful mentoring program. Investigations on the role, responsibilities, and metrics for evaluating the coordinator are also warranted. Additional research into details of each of the six phases of the program is needed. Other particulars of carrying out and sustaining a successful mentoring program, as outlined in other chapters of this book, could also be considered for research.

Conclusions

Mentoring is crucial to individuals’ personal and professional development in nearly any work setting. Understandably, the specifics of any formalized mentoring program will vary according to organizational vision, mission, culture, and values. Regardless of these differences, in order to be functional, a mentoring program must have a dedicated program director/coordinator to spearhead the development of the program’s characterization, framework, design, implementation, assessment, evaluation, and refinement.

In this chapter, we accordingly list the characteristics and duties of high-quality mentoring program coordinators and give suggestions for how to evaluate and support them. We also detail six phases of mentoring program creation, execution, evaluation, and sustainability. These are: defining the program, preparing for mentorship, designing the program, implementation, program evaluation, and funding and sustaining the program. These key phases are indispensable to the success of both the program and its coordinator.

Optimally, coordinators are supported by a mentoring committee and should have enthusiasm for mentoring, as well as strong communication, listening, and leadership skills. Because mentoring programs are dynamic, complex systems (Koczka, 2017, p. 259), a program coordinator who is both knowledgeable and passionate can help stakeholders navigate the mentoring process.

Coordinators and their committees are tasked with spearheading the research, design, implementation, evaluation, and improvement of the mentoring model used; this process requires them to evaluate the type of program that best fits their institution and to clearly define the roles of the stakeholders in that program. They then gauge the program’s effectiveness through coordinator-led assessments and evaluations, which allow for the continued, iterative improvement and possible expansion or contraction of the program. Additionally, coordinators and their committees should also develop and provide the administrator, mentor, and mentee with the training and resource materials needed to implement an effective mentoring model. This dynamic process understandably requires that individuals be adaptable to the needs of the organization and of those involved.

References

Allen, T. D., Eby, L. T., & Lentz, E. (2006). The relationship between formal mentoring program characteristics and perceived program effectiveness. Personnel Psychology, 59(1), 125–153.

Bell, A., & Treleaven, L. (2011). Looking for professor right: Mentee selection of mentors in a formal mentoring program. Higher Education, 61, 545–561.

Benabou, C., & Benabou, R. (2000). Establishing a formal mentoring program for organizational success. National Productivity Review: The Journal of Organizational Excellence, 19(4), 1–8.

Crisp, G., & Cruz, I. (2009). Mentoring college students: A critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Research in Higher Education, 50(6), 525–545.

Crockett, L., & Smink, J. (1991). The mentoring guidebook: A practical manual for designing and managing a mentoring program. National Dropout Prevention Center.

Dawson, P. (2014). Beyond a definition: Toward a framework for designing and specifying mentoring models. Educational Researcher, 43(3), 137–145.

Donovan, A. (2010). Views of radiology program directors on the role of mentorship in the training of radiology residents. American Journal of Roentgenology, 194, 704–708.

Ehrich, L. C., Hansford, B., & Tennent, L. (2004). Formal mentoring programs in education and other professions: A review of the literature. Educational Administration Quarterly, 40(4), 518–540.

Farah, R. S., Goldfarb, N., Tomczik, J., Karels, S., & Hordinsky, M. K. (2020). Making the most of your mentorship: Viewpoints from a mentor and mentee. International Journal of Women’s Dermatology, 6, 63–67.

Ganser, T. (1995, April 29). A road map for designing quality mentoring programs for beginning teachers [Paper presentation]. Wisconsin Association for Middle Level Education Annual Conference, Stevens Point, WI, United States.

Griffiths, P. A., Alberts, B. M., Brinkman, W. F., Cowling, E. B., Dinneen, G. P., Dresselhaus, M., Fox, M. A., Gomory, R. E., Greenwood, M. R. C., Hearn, R. P., Koshland, M., Larson, T. D., Majerus, P. W., McFadden, D. L., Shine, K. I., Tanenbaum, M., Wilson, W. J., & Wulf, W. A. (1997). What is a mentor? In National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, & Institute of Medicine, Adviser, teacher, role model, friend: On being a mentor to students in science and engineering (pp. 2–3). National Academy Press.

Hackmann, D., & Wanat, C. L. (2008). The role of the educational leadership program coordinator: A distributed leadership perspective. International Journal of Educational Reform, 17(1), 64–88.

Jacobi, M. (1991). Mentoring and undergraduate academic success: A literature review. Review of Educational Research, 61(4), 505–532.

Klinge, C. M. (2015). A conceptual framework for mentoring in a learning organization. Adult Learning, 26(4), 160–166.

Koczka, T. (2017). The role of the mentoring programme coordinator. In D. A. Clutterbuck, F. K Kochan, Lunsford, L. Dominguez, N. &Haddock-Millar, J. (Eds) (2017). The SAGE handbook of Mentoring. Sage.

Lunsford, L. G. (2016). A handbook for managing mentoring programs: Starting, supporting, and sustaining effective mentoring. Routledge.

McCann, T. M., Johannessen, L. R., & Liebenberg, E. (2010). Mentoring matters. The English Journal, 99(6), 86–88.

Putsche, L., Storrs, D., Lewis, A. E., & Haylett, J. (2008). The development of a mentoring program for university undergraduate women. Cambridge Journal of Education, 38(4), 513–528.

Sanchez, L. L. (2018). Creating a sustainable mentoring program [Master’s thesis, Eastern Washington University]. EWU Masters Thesis Collection. https://dc.ewu.edu/theses/531

Silet, K. A., Asquith, P., & Fleming, M. F. (2010). A national survey of mentoring programs for KL2 scholars. Clinical and Translational Science, 3(6), 299–304.

Zwikael, O., & Meredith, J. (2019). Evaluating the success of a project and the performance of its leaders. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 68(6), 1745–1757.

Appendix

Mentoring Program Coordinator Position

Overview

State/University located at the central campus invites applications for a position as Mentoring Program Coordinator. This position is 12 months, full-time, and benefited. The anticipated start date is the beginning of the fall semester. The Mentoring Program Coordinator plans and oversees the design, implementation, and evaluation of the mentoring program as well as coordinates the operational activities pertaining to resources, support, recruiting, education, and events that promote and provide a welcoming campus for all students. The position will also provide leadership, guidance, continuity, and direction for the Mentoring Program.

Responsibilities

Reporting and Supervisory Responsibilities:

The Program Coordinator reports to the Office of the Provost. This position will supervise the design and implementation of the Mentoring Program and train faculty and staff.

Duties and Responsibilities:

- Works with key stakeholders to conduct a needs assessment to determine if and whom the mentoring program will help.

- Works with key stakeholders to determine the program’s organizational structure.

- Works with key stakeholders to determine the model for how programmatic decisions are made and by whom. For example, are programmatic decisions made solely by the program coordinator, executive team, or steering committee? Regardless, the program coordinator oversees this process.

- Works closely with their supervisor regarding funding.

- Oversees the development of an operational definition of mentoring to guide the program.

- Oversees the development of a theoretical framework to guide the development of the program.

- Oversees the development of the program’s goals, objectives, and outcomes.

- Oversees the type of mentoring to be employed (e.g., peer or hierarchical).

- Oversees the program’s scope; who will and will not be included? How many mentees can the program support? How many mentors are needed to support the program?

- Develops a proposal of the program to be shared with stakeholders.

a. If the proposal has a research component, the mentoring program coordinator must have the skillset to receive Institutional Review Board approval.

b. The communication plan is made explicit within this proposal, which describes how the program coordinator will keep all stakeholders informed of the program, including evaluation of the program.

c. This proposal includes the details of what data will be collected, how this data will be collected, and how it will be analyzed for the summative evaluation. - Oversees the program’s procedures and policies and how these are communicated and executed.

- Clarifies the roles and responsibilities of mentors, mentees, executive or steering committee, and support staff.

- Develops and implements a marketing plan.

- Recruits, selects, and trains mentors and mentees. Collects evaluation data on training.

- Oversees the matching of mentors and mentees based on mentoring typology.

- Creates a plan to monitor and encourage the development of mentoring relationships.

- Creates a quality-assurance plan to address dissatisfied mentoring relationships.

- Provides formative evaluation throughout the program.

- Provides summative evaluation of the program.

- Performs miscellaneous job-related duties as assigned.

Qualifications

Minimum Qualifications:

- Master’s degree in a related field or higher

- A high degree of self-motivation

- Demonstrated strong written and oral communication skills

- Proficient ability to use current electronic communication tools, such as virtual meetings, email, texting, etc.

- Education or comparable experience level that equals or surpasses those the coordinator supervises

- Demonstrated energy and enthusiasm for mentoring

- Strong interpersonal skills and ability to interact with a wide variety of individuals

- Ability to teach, manage, and engage people

Preferred Qualifications:

- Experience in mentoring

- Experience in management

- Experience working with Institutional Review Boards

- Experience in proposal development

- Experience in conducting a needs assessment

- Experience in data management

- Experience in statistical analysis

- Experience with formative and summative program evaluation

Evaluation

The Mentoring Program Coordinator will be expected to be evaluated annually by the Office of the Provost. The Program Coordinator will be expected to present on the design, implementation, and results of the previous year, as well as recommendations for the program moving forward.

Support

The Office of the Provost will provide resources, budget, and training for the Program Coordinator to assist them in the implementation of the Mentoring Program. An office, computer and peripheral equipment, office phone, and other required resources will be provided. An assistant to help with data collection and analysis will be provided. A budget will be provided for the Program Coordinator in discussion with the Office of the Provost. It is expected that the Program Coordinator will attend at least one Mentoring Conference each year, and a budget will be provided to facilitate attendance. The Program Coordinator is encouraged to present the design and results of the mentoring program. Funds needed for presenting at conferences will need to be discussed with the Office of the Provost.

Required Documents

Along with the online application, please attach:

- Resume

- Cover letter

- Letters of recommendation

Salary

Commensurate with experience

ADA

Employees work indoors and are protected from weather and/or contaminants, but not necessarily occasional temperature changes. The employee is regularly required to sit and often uses repetitive hand motions.

University Highlights

To be determined by the University or College

Notice of Nondiscrimination

In its programs and activities, including in admissions and employment, the University does not discriminate or tolerate discrimination, including harassment, based on race, color, religion, sex, national origin, age, genetic information, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, disability, status as a protected veteran, or any other status protected by University policy, Title IX, or any other federal, state, or local law.