11 Preparing the Effective Mentee

Dionne Clabaugh

Abstract

The purpose of this chapter is to help the mentoring program director create, implement, and evaluate academic mentoring programs after identifying structures that can effectively prepare their mentors and mentees for a successful mentoring experience. Some of the considerations explored are mentor program structures that are relationally based, goal-oriented, and grounded in autonomy supportive strategies. This chapter opens with the author’s lens in order to describe a human development approach to mentoring and then how to prepare mentees to be self-directed. The third section portrays mentoring program structures that promote self-directed mentees. This chapter concludes with generalizable findings and recommendations based on key lessons learned. It is the author’s belief that mentees and mentors are learners who benefit most when they (a) have a clear understanding about the mentoring program’s purpose and objectives, (b) understand the rationale for and benefits of participating in a mentoring relationship, and (c) hold accurate schema for what is expected of them regarding program tasks and activities.

Correspondence and questions about this chapter should be sent to the author: dionne.clabaugh@gmail.com

Acknowledgments

This chapter is dedicated to faculty mentors and mentees who want to grow themselves and others as strong facilitators of learning. I am ever grateful to Dr. David Law for his writing guidance and support—he is a gem! I very much appreciate the ongoing leadership of Dr. Betty Jones, Judy Magee, MA., and Dr. Nora Dominguez. Their mentorship inspires me to move toward excellence as an effective educator and learner, mentor and mentee.

For over 40 years in education, I have been encouraged daily by all learners. They benefit across their lifespan when their educators teach in ways that reach them, mentor them through and for positive impact, and engage them in contextualized experiences that transform their approach to growing whole learners at all ages and stages.

Introduction

Mentor, know thyself. Mentor, know thy mentee! The frame of reference for this chapter is toward developing mentees who are very successful because of their mentor’s guidance and modeling of autonomy supportive (Jang et al., 2010) strategies, which inherently activate engagement and self-directedness. In other words, the better a mentor knows the full context of their mentee’s approach to learning, living, and communicating, the better their mentee’s outcomes will be.

You may think that knowing your dissertation student well does not matter much. However, if you perceive your dissertation mentee as a future colleague, then your investment now benefits you, them, and your field of study from today forward. You may think investing this much in your junior faculty mentee will take too much time away from your other responsibilities and projects; however, if one values the funds of knowledge you both bring to the table, you have an opportunity to be enlivened after each conversation. These are the frames of reference that I apply to my practice of mentoring—we are engaged in human development across the lifespan.

This chapter provides the reader with an overview of the contextual spaces in which an impactful mentoring relationship lives and offers theoretical strategies you can incorporate into your practice of, and engagement in, your own mentor-mentee relationships. The chapter is divided into the following four sections: (a) The Author’s Lens, which provides background for this human development approach to mentoring; (b) Preparing Mentees to be Self-Directed, because intrinsically motivated mentors and mentees apply volition for their growth; (c) Mentoring Program Structure to Promote Self-Directed Mentees, to illustrate how and why all program practices promoted mentor-mentee engagement; and (d) Findings and Recommendations, to summarize lessons learned from a human development perspective.

The Author’s Lens

I began my doctoral program asking: What makes learning—learning—happen? I was interested in the interplay between the content, content delivery within the learning environment, the facilitator’s context for teaching and the learner’s context for learning. As a learner and practitioner in three spaces, I learned “what makes people tick” and “why people do what they do” from therapeutic, developmental, and organizational lenses. This learning prompting my human development approach to mentoring based on my bachelor’s degree and practicum in music therapy, a community college certificate program in lifespan development, and my master’s degree in organization development. In all three spaces, learning was applied to real-life situations through projects that we designed, implemented, assessed, and presented. In the music therapy program, I learned how and why the structures of music are utilized to design, implement, and assess treatment plans to increase a client’s functioning. In the lifespan development program, I learned about emergent curriculum and making learning visible (Ritchhart & Church, 2020). In my organization development degree program, I learned how to identify and select relevant assessment tools to evaluate organizational health based on the effectiveness of its structures and attention to human factors before designing an intervention to increase functioning and productivity. Knowing what and whom one is working with is central to promoting meaningful and sustainable change.

In my music therapy degree, from 1973–1983, I learned that individual change and increased functionality are primary goals. Change was described as progress over time and was assessed by comparing baseline functionality to end-of-treatment functioning in any developmental area: physical (cerebral palsy, multiple sclerosis, spina bifida), cognitive (Down’s Syndrome, stroke, speech delays, sensory processing differences), and mental (depression, schizophrenia, guilty by reason of insanity). Treatment plans were developed to promote observable, incremental steps toward what was considered socially acceptable functioning while ensuring the highest quality of life possible for every individual.

Across 40+ years teaching in preschool, elementary, and college environments, I see change as developmental, individualized, and situated in social groupings. The quality of a learner’s growth and development relies on skill-building across developmental domains. One critical outcome is for people to develop social and emotional skills to interact and express themselves in socially appropriate ways throughout their life, initially learned in their family and cultural contexts, then expanded in school learning environments. Growth, development, and learning are promoted through developmentally appropriate practices (Bredekamp & Copple, 2009) coupled with the learner’s volitional (i.e., self-selected) exploration of their environment and materials and participation in skill- and knowledge-building activities across developmental domains (California Department of Education, 2021). These domains are typically categorized as social-emotional; physical; cognitive; language; and health, arts, sciences, and social sciences in preschool through high school and categorized as professional or vocational skill sets in higher education.

In my organization development degree and ongoing consulting practice, from 1989 to present, I came to believe that change is based on increased individual functionality and increased team or workgroup productivity. Work group quality is assessed through a systems lens—what are the processes and procedures used to get work done? How well do employees know what is expected of them? To what extent do employees engage with civility and respect? How strong is their customer service and what risks and wastes impact market share and profit? The answer, of course, is that the quality of an individual’s contribution impacts overall effectiveness.

I apply this integrated lens to address the purpose of mentoring: to grow humans into better versions of themselves, regardless of their work environment. People use volition and agency to change themselves. Thus, the mentor’s role is to integrate their mentee’s context into the mentoring relationship. The mentor then constructs informed and reasonable expectations for their mentee’s readiness, willingness, and ability to learn and grow.

Why so much about my background? Most people do not have degrees and work experience in therapeutic, business, and education environments. It seems important that readers understand how my mentoring practice integrates these lenses and why I want to increase an individual’s quality of life—by engaging them in their own development. Mentoring is a learning partnership that begins with interest and commitment and moves through the stages of negotiation, cultivation, and ending (Clabaugh & Dominguez, 2022).

Knowing this context offers mentors my frame of reference to make decisions about applying these practices and advice to mentoring. Just as each mentor has agency and volition to grow into a well-prepared mentor, their mentees use agency and volition to become well-prepared mentees.

Preparing Mentees to be Self-Directed

Many mentees are ready, willing, and able to be mentored and enter the program prepared and ready to set goals, indicate willingness to engage in program activities, and demonstrate their ability to apply guidance. These mentees are self-directed because they have internal resources (readiness, willingness, and ability) to follow through and succeed. Other mentees are unprepared for mentoring, which can frustrate well-intentioned mentors with thoughtful preparation. However, what is actually happening? Mentees need resources, modeling, and opportunities to understand what it means to be a mentee, especially to form accurate perceptions and expectations for being mentored.

Mentors are human developers. Mentors need to know how to respond to self-directed and non-self-directed mentees by applying strategies that develop mentee agency for learning and development. One’s volition is a motivator, and every mentee’s motivational context is individualized. This second section describes (a) what it means to be self-directed; (b) what dispositions self-directed mentees bring to the mentoring relationship; (c) suggestions to activate mentee dispositions of readiness, willingness, and ability; and (d) mentee motivational resources and self-determination.

What Does it Mean to Be Self-Directed?

Self-directed means taking responsibility, initiating interactions, seeking help, resources, or guidance, and following through. Self-directed learners are self-aware, know their limitations and interests, and willingly apply effort to meet goals. Self-directed goal setting means choosing meaningful, achievable goals that lead to greater accomplishments (Clabaugh & Dominguez, 2022).

Self-directed mentees take charge of their learning within the mentoring relationship. They use agency to set and act on goals, use volition to seek help, and ask for information and tools to promote their learning, growth, and success. Self-directed mentees use emotional intelligence to communicate effectively; they recognize their impact on others and others’ impact on them (Clabaugh & Dominguez, 2022). For example, active listening skills are used to clarify and ensure they understand what is suggested or conveyed.

The self-directed mentee communicates their desire and intention to improve their performance and effectiveness and motivate themselves for action. Mentees respond to their mentor’s help toward success and recognize their mentor’s efforts toward making themselves available. The mentee can then engage with the mentor to increase their skills and knowledge (Dominguez, 2017).

Self-directed mentees realize that goals are achieved over time. The mentee applies a growth mindset (Dweck, 2007) by keeping an open mind and believing they can learn new strategies and meet challenges. In practice, mentees with a growth mindset adopt a “not yet” attitude in response to making mistakes. This attitude indicates that mentees see errors as learning moments rather than evidence that they cannot learn, when applying their mentor’s suggestions. The self-directed mentee accepts and learns from these mistakes and missteps. The mentee recognizes their progress and asks questions (Miller, 2018) for guidance, reassurance, and feedback. They are accountable and follow through because they want to reach their goals.

A self-directed mentee acknowledges their shortcomings and is accountable. For example, if mentees do not listen well or tend to procrastinate, they could open a conversation to discuss these tendencies with their mentor. The pair could then explore options for new skills, such as active listening or using productivity tools. A skilled mentor then models listening and planning skills into mentoring conversations, and the self-directed mentee may notice this. A self-directed mentee works hard to follow through and be successful. They may also initiate check-in conversations to describe progress and hear additional suggestions or insights.

What Dispositions Do Self-Directed Mentees Bring to the Mentoring Relationship?

Successful mentoring relationships are built on effective mentor-mentee interaction and engagement. Mentee dispositions center on their readiness, willingness, and ability to engage in mentoring activities. Giving mentees opportunities to deepen dispositions in five specific areas builds effective mentoring relationships where mentees can be self-directed. These five specific dispositions discussed next are (a) being ready, willing, and able to engage and connect; (b) being willing to try new skills and strategies; (c) being willing to co-construct new knowledge; (d) being able to develop efficacy for learning; and (e) being able to set and work toward goals. Each of these five dispositions will be described, then a section of suggestions to leverage dispositions to build strong mentoring relationships will follow.

Being Ready, Willing, and Able to Engage and Connect

Learning is a social-emotional-cultural interaction that requires being introduced to something new, interacting with the information, integrating it into one’s ways of thinking and working, and then trying and practicing new skills. In the mentoring relationship, a mentee learns from the mentor directly, not necessarily from a book or resource. Effective mentoring is a healthy relationship based on respectful, observant, positive interactions that are rooted in self-awareness. To begin this relationship, the mentee must be ready, willing, and able to engage and connect—to show up and be present—with their mentor. Mentees must feel they can reach out to their mentor for help and guidance because they are in pain of some sort, that is, under-resourced, frustrated, or inexperienced. A self-directed mentee knows they need additional information and skills to make desired improvements.

A mentee in a formal hierarchical mentoring relationship (see Chapter 3 on diverse form of mentoring relationships) may subordinate themselves and believe they should not ask questions or push back on their mentor, even when the tool or approach suggested does not fit or work for the mentee. In a formal pairing the mentor is highly skilled and the mentee is a novice, which sets up a power differential in which mentees may incorrectly assume they made a mistake, feel guilty, and then disengage from the mentor. In effective mentor-mentee relationships, discords are addressed even when it is difficult to discuss. A self-directed mentee uses reflection to understand and then describe their experience. The effective mentor makes themself available to listen and then promotes a cooperative conversation to identify more viable suggestions or strategies.

Being Willing to Try New Skills and Strategies

A prepared mentee knows they are missing key skills, resources, or strategies to be successful and/or meet professional, career-oriented, academic, intrapersonal, or psychosocial goals. A self-directed mentee identifies and respects their mentor’s skills that help the mentee advance. The mentee asks interesting and courageous questions, listens carefully, and then applies the strategies and advice provided (Clabaugh & Dominguez, 2022).

As many readers know, Bandura conducted experiments on the impact of “expert models” of behavior, such as a parent, teacher, or businessperson, to understand the impact of the expert’s modeling on the decisions made by the novice, or lesser-experienced person in similar situations. Some readers may recall his studies on aggressive behavior modeling with the Bo-bo doll, which concluded that children will imitate behavior observed in trusted adults, even if it is aggressive or hurtful in some way. Similarly, the mentee sees their mentor as a guide and copies the observed behaviors. Mentors can leverage this disposition by providing opportunities for the mentee to observe mentor behaviors or can create opportunities for the mentee to practice skills under protective guidance within the mentor’s setting. The self-directed mentee is eager to work alongside their mentor, agrees to the mentor’s suggestions, and practices the strategies modeled by their mentor.

Being Willing to Co-Construct New Knowledge

The self-directed mentee wants to participate in a mentor-mentee relationship to co-construct success. Mentees ask questions about what their mentor knows and advises. Mentees use resources suggested by their mentor and open conversations about this content and information. Mentees often feel bad if they skip a meeting and appreciate the mentor’s investment in their success and growth. These relationships are reciprocally rewarding, sustaining engagement and follow-through, building trust, and allowing each person to be fully themself in the relationship.

Self-directed mentees open conversations to share their thinking and make their learning visible. Mentees ask for specific feedback and accept it gracefully, knowing that the mentor’s intention is to develop them and help them succeed. Feedback conversations are often perceived as scaffolds for improvement, and the self-directed mentee applies this feedback faithfully.

As the mentee becomes more successful, their efficacy and confidence grow. Success then provides direct experiential evidence of increased skills, which leads to mentee efficacy for taking new risks and applying new strategies. Soon, the mentee applies these new skills and continues seeking feedback while acting independently to achieve new goals.

Being Able to Develop Efficacy for Learning

If the goal is to solve a problem, then the mentor helps the mentee organize, reflect, learn new approaches, and identify solutions. The mentee is observed by the mentor, then feedback is used to encourage the mentee’s confidence and competence. “The link between personal agency and a teacher’s [mentor’s] efficacy beliefs lie in personal experience and [their] ability to reflect on that experience and make decisions about future courses of action” (Bray-Clark & Bates, 2003, p. 14).

Thus, when the mentee and mentor use cooperative problem solving, the mentee feels efficacious, willingly shares their funds of knowledge, and stays open to new ideas. A self-directed mentee tracks their efficacy levels in various situations and seeks input to increase success. Efficacious mentees believe they can learn and make progress.

Being Able to Set and Work Toward Goals

A prepared mentee is goal-oriented and uses self-directedness to accomplish their goals (Clabaugh & Dominguez, 2022). They perceive the mentor as a resource and may have several mentors for different goals, such as in situational mentoring (Clutterbuck & Lane, 2004) or developmental mentoring (Murphy & Kram, 2014) relationships. Being goal-oriented means having the desire and intent to make progress, then creating and following a plan of action to accomplish something important (Ryan & Deci, 2009).

Mentees have high hopes for their progress and set short- and long-term goals and are prepared for conversations and work sessions to achieve their goals. Goal-oriented mentees are committed to their own learning and use various communication strategies to manage these goals (Clutterbuck & Lane, 2004). For example, a graduate student mentee wants to publish, so asks their mentor to suggest journal articles and books as exemplars for scholarly writing. The mentor and mentee discuss elements of publishable manuscripts, which directly engages the mentee in the writing and publishing processes. In addition to receiving suggestions and resources, the mentee may be invited to contribute to their mentor’s current work and might be included as a co-author.

This concludes the focus on the five dispositions to be self-directed. The third section of preparing mentees to be self-directed gives suggestions on how to activate the mentee’s dispositions of readiness, willingness, and ability.

Suggestions to Activate Mentee Dispositions of Readiness, Willingness, and Ability

To approach each mentoring conversation with a human development lens, mentors must ask themselves the following questions: What can I do and say to help this mentee improve the quality of their work, life, or self? Developmentally, where is this mentee’s motivation (more externally focused vs. more internally focused)? In what ways do they regulate themselves and their work, and how effective is this regulation? How might I describe their emotional maturity? How well do they follow through? What do they not recognize about themself and their approach to their own development?

Consider asking your mentee these same questions after reflecting on the various ways they might respond. These answers help you identify your mentee’s capacity to learn from you and help you gauge how much interest they have in doing so. The desired outcome is increased capacity for learning. Capacity for learning increases when a human development approach is used to engage authentically. Mentor stories and suggestions are meaningful and help mentees trace changes over time, which mentees can then overlay for themselves: “I see how my mentor approached this, and I can apply their strategies to myself.”

Developmental conversations are in direct contrast with transactional interactions. In transactional interactions, mentors tell mentees what to do or direct them to use specific skills or resources to make progress. In this transaction, the mentee is objectified, and the conversation focus is primarily on the task, goal, skill, or outcome. Transactional interactions can be dehumanizing at worst and are often demotivating because the mentee’s locus of control is external—the mentee is encouraged to rely on an expert source outside of themself, which thwarts self-directedness.

The mentoring relationship may begin transactionally, where the mentee asks for guidance or suggestions from their mentor. However, the relationship is most effective and rewarding when mentor-mentee pairs discuss their thinking, brainstorm ideas together, and cooperatively identify desired outcomes. In this way, the mentee has multiple opportunities to use self-directedness, rather than dependence on someone else, to meet their goals. The mentor guides while being a sounding board, brainstorming partner, and reflective listener.

Importantly, mentees recognize the multidimensionality of their mentoring relationship. Developmental conversations bloom into trusted relationships that last for years, traversing life and work stages, simply because the mentor listened thoughtfully, invited the mentee to articulate their perspectives, feelings, and questions, and actively heard mentee experiences. Self-directed mentees are then able to co-construct strategies to replace concerns about competence; workflow worries are smoothed through courageous conversations and reflective practice. Efficacy develops when using effective and sustainable ways of working.

Developmental conversations invite mentees to be the agent of their work, tasks, and goals, appealing to their internal locus of control. When mentors ask, “From here, how do you want to move forward? What steps will you take toward your intended outcomes?” Mentors relate first to the mentee, then to the tasks, strategies, and outcomes. Developmental approaches build self-efficacy, the belief in one’s capacity to accomplish what one sets out to do (Bandura, 1997). Mentees must become aware of and encouraged to increase their self-efficacy to be self-directed.

According to Bandura (1997), self-efficacy is when a person feels confident in their abilities and then controls their motivation, environment, and behaviors to ensure ongoing efficacy. Self-efficacious mentees evaluate their progress, adjust their goals and approach, and have high energy for goal attainment—they are effectively self-efficacious and know they can succeed. Then they seek more help because they recognize their need for additional guidance, tools, strategies, and perspectives.

Help-seeking is necessary for self-regulated learning (Shunk & Zimmerman, 1998). Self-regulated learners are aware of their actions, identify the outcomes of those actions, and assess the next steps for success. Help-seeking is critical for impacting one’s success. Recall the dispositions described above: self-directed mentees are ready, willing, and able to engage and connect and know they need help to make desired improvements. It is one thing to know help is needed and another to actively seek that help.

The most important aspect of successful mentoring is that mentees accept and apply the help they are offered. Self-directed mentees are self-determined (Clabaugh & Dominguez, 2022) when they seek and accept help. Mentees’ intrinsic motivation for growth and development is activated, so they become more engaged and successful (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Help-seeking, applying intrinsic motivation, and being engaged are characteristics of the self-directed mentee. However, many mentors do not know how to assess their mentee’s motivation level, which can positively or negatively impact the mentee’s self-directedness. Understanding motivation through the lens of self-determination theory gives mentors a valuable tool for promoting self-directedness within the mentor-mentee relationship. Assessing the mentee’s motivation level is the final section for preparing the mentee to be self-directed.

Mentee Motivational Resources and Self-Determination

In self-determination theory, “to be motivated means to be moved to do something. A person who feels no impetus or inspiration to act is thus characterized as unmotivated, whereas someone who is energized or activated toward an end is considered motivated” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 54). To be self-determined is to use one’s decision-making capacity and then apply motivation and effort to follow through (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

There are three levels of motivation: amotivation, extrinsic motivation, and intrinsic motivation, as described in the self-determination theory’s motivation continuum (Deci et al., 1991). Motivational resources come from both one’s external environment and one’s internal environment. The external environment consists of the learning or working environment (structures, procedures, policies, ways of working, interactions with people), and the internal environment includes one’s characteristics and internal processes (temperament, habits of mind, levels of efficacy, volition, regulation, and agency as well as how they perceive their success and failure). According to self-determination theory, external motivators include earning rewards or recognition and avoiding negative consequences, and internal motivators include pride, goal attainment, and joy (Ryan & Deci, 2002).

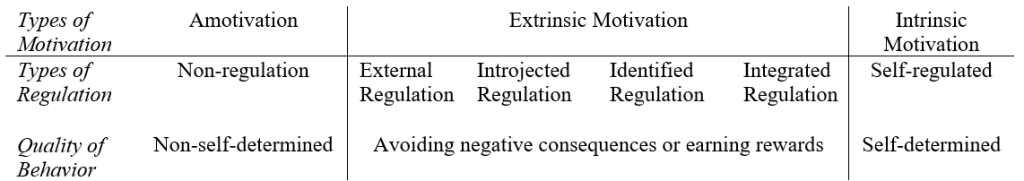

Ryan and Deci’s motivation continuum (Figure 11.1) is a model of six motivation strategies, types of self-regulation associated with each motivation strategy, and the quality of behavior moving from less determined (extrinsically motivated) to more determined (intrinsically motivated).

Figure 11.1

Self- Determination Continuum With Types of Motivation and Regulation

Note. From “An Overview of Self-Determination Theory,” by R. M. Ryan and E. L. Deci, in E. L. Deci, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), 2002, Handbook of Self-Determination Research, pp. 3–33, University of Rochester Press.

Looking at the left column, people who are amotivated present as not interested. They are “checked out,” disengaged; they do not join in or participate. At the other end of the continuum, intrinsically motivated people demonstrate self-determination, engage volitionally, and use self-regulation for personally meaningful reasons such as joy, pleasure, or aspiration. The center section shows four levels of extrinsic motivation, in which people rely on the various elements of the external environment to activate their regulation and engagement.

People activated by external regulation are motivated by avoiding negative consequences or earning rewards for participation and engagement, regardless of interest, goals, or needs. People use introjected regulation when feeling controlled by guilt or shame, so they either avoid these feelings or increase their sense of self-worth, especially when they believe the task is not important, useful, or interesting. Identified regulation means placing importance on goals or outcomes, such as working diligently toward a goal because recognition is valued. Integrated regulation is autonomous, yet there is reliance on external motivators to engage or follow through. In this case, the goal or task is interesting or important to one’s identity and future prospects, such as advancement or promotion (Clabaugh, 2013).

In mentoring relationships, it is valuable to know whether there is unresolved trauma. Traumatic experiences can lead to withdrawing from challenges, seeking perfection, resisting help or resources, or lashing out when frustrated, indicating lower emotional regulation. People who were criticized for not “measuring up” or who were praised for being compliant may enter a mentor-mentee relationship with expectations of punishment and praise or resist relationship-building. Mentees with trauma may be more comfortable with transactional relationships because the relational expectations are lower. However, this threatens opportunities for true change and development.

Although self-determination theory has not been broadly studied in mentoring relationships, it has been studied extensively in other learning relationships: teacher-student, manager-employee, coach-athlete, doctor-patient, and parent-child (see https://selfdeterminationtheory.org/). In all cases, findings indicate that learners have increased engagement and success based on the activation of their intrinsic motivation.

I use self-determination theory to develop mentoring programs. I have observed self-determined dynamics in mentor-mentee pairs and mentoring cohort groups for nearly 10 years. In most cases, I can confidently say that intentionally responding to the dynamics of self-determination, motivation, and engagement positively impacts mentor-mentee relationships by encouraging growth-oriented professional interactions with strong engagement and program outcomes.

To ensure successful mentoring programs, program directors and mentors are advised to observe mentee behavior to assess motivation levels, regulation types, and identify motivational sources and regulators. Program directors thus assess the cohort’s overall motivation, and mentors assess their mentee’s motivation. Then, program directors can respond collectively and mentors respond individually to attain the critical goal of developing self-directedness in the mentees. Such intentional responses increase mentee motivation and regulation by promoting their self-determination and self-directedness.

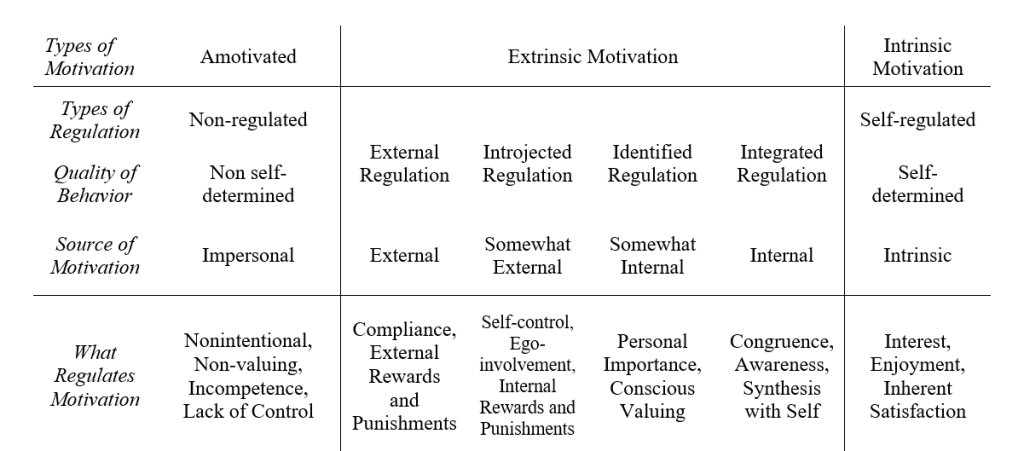

Figure 11.2 labels the types of motivation (top row) related to their regulation (second row), behavior (third row), and sources of motivation (fourth row). The fifth row describes a person’s internal processing that regulates their motivation at each level along this continuum. During the first part of an initial conversation program director-mentee applicant, such as a conversational intake interview, careful observation and reflection form a baseline assessment of each applicant’s motivation and regulation types. In the second part of the initial conversation, the program director can confirm their assessment by asking situated questions that elicit nuanced evidence of the applicant’s types and sources of motivation and regulation.

Figure 11.2

Self-determination Motivation Continuum with Motivation Sources and Regulators

Note. From “An Overview of Self-Determination Theory,” by R. M. Ryan and E. L. Deci, in E. L. Deci, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), 2002, Handbook of Self-Determination Research, pp. 3–33, University of Rochester Press.

Looking first at the left column, a person who is amotivated (uninterested, does not involve themselves, disengaged) does not take any action, so there is no reason to regulate I. They do not have goals, so there is no need to be self-determined or self-directed. Their motivational source is impersonal, so there is no reason to activate agency or volition. Thus, what regulates one’s motivation (i.e., what sustains their lack of motivation) are perceptions of no value, incompetence (theirs or other’s), and a lack of personal control.

Understanding how amotivated people behave (by interpreting the meaning of observed behaviors) helps mentors and program directors effectively assess mentees who appear disengaged and informs intentional decisions about how to respond. There are two approaches: do not accept amotivated mentees into the program or invest a predetermined amount of time and effort to turn amotivation into motivation. The latter choice might work for mentees with low efficacy and high competence, identified as impostor syndrome (Vian, 2021). The effort and time required in the latter case must be acknowledged because mentee success takes longer and is not guaranteed.

Most people are extrinsically motivated by structures or policies outside themselves. Having a variety of responses to use during conversations is essential so that each mentee feels understood and included, building trust and engagement. Different responses address different motivation levels while ensuring engagement.

To assess motivational levels in an intake conversation, label the type of motivation based on their response. For example, an applicant says they thrive in environments where they “can shine” and “make a strong impact” is assessed as either introjected regulation (ego-involvement) or identified regulation (personal importance). To determine which level is more accurate, situate a follow-up question relating to past accomplishments (introjected regulation), inquire about what they value and ways they act on these values (identified regulation). The responses that are accompanied with energized body language confirm their level of extrinsic motivation.

Always respond as inclusively as possible. To someone regulated by compliance, one can say, “Our policies say that every mentee must participate in orientation before signing into the mentoring program.” Those motivated by external rewards could be told, “After completing orientation, you will receive a certificate of completion that enters you into the mentoring program.” A small number of people are motivated by avoiding punishment, so an effective response would be, “People who do not complete the program orientation will be placed on a wait list for upcoming orientations, which are held in August each summer.” Note that these responses incorporate two strategies that support autonomy (described in a later section): positive phrasing and providing information.

Fewer people are motivated intrinsically for workplace activities than extrinsically. Intrinsic motivation characteristics are self-regulated and self-determined, and volition is used to engage and succeed based on interest, enjoyment, and inherent satisfaction. These mentees typically ask questions, seek help, and take initiative; they do not need reinforcers or external structures to get started. Intrinsically motivated people may work longer hours for lower salaries. They derive deep personal pleasure in their work and often experience flow (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990), meaning their sense of time dissipates, and they work at the top of their capacity on meaningful goals or projects.

Intrinsic motivation is often assessable based on people’s hobbies and “side gigs”—doing things they value and love for sheer pleasure and joy. Quite a lot of people’s time and money are spent on their hobbies, and great satisfaction is derived from them. During intake conversations or program orientation introductions, ask people to describe their hobbies so intrinsic motivators can be assessed and relationships can be built around commonalities, leading to cohesion and unity.

You may have heard people say, “If you paid me, it wouldn’t be a hobby anymore.” This sentiment indicates that for intrinsically motivated people, external motivators diminish experiences of happiness and fun. It is interesting that managers believe they need to offer rewards or punishments no matter what. However, the person motivated at higher levels does not benefit from extrinsic motivators. Research in self-determination theory describes this dynamic (Ryan & Deci, 2002) and suggests that when motivators below one’s actual level of motivation are applied, the person disengages.

Overall, mentoring program directors and mentors can pay close attention to their mentee’s demonstrations of motivation from the very beginning of the relationship. Program directors can identify how each mentee responds in various situations and can guide mentors to (a) match various motivators to various situations and (b) to promote the mentee’s use of more intrinsic levels of motivation more frequently. The mentor must observe their mentee’s responses to various situations: What does the mentee need in order to accomplish a boring or undesirable task? What choices does the mentee make to approach success and take initiative? What are the mentee’s hobbies?

The mentor can then make intentional suggestions that fit the type of motivation best suited to succeed in any situation. Contextually, if the mentee views their future self as a presenter or public speaker, then fame and recognition are viable motivators, and ToastMasters® may be a perfect suggestion. Alternatively, if the mentee’s context is to advance career skills or increase employability and they enjoy being in the community, then a service-learning opportunity or volunteer role might be appealing to them. If the mentee wants to spend most of their energy on composing and playing gigs yet needs to pay the rent, then a job with reasonable pay, benefits, and little to no take-home responsibly would fit well for them. In this second context, the job is the mentee’s means to an end, and the duties are not important.

In summary, the mentee who is ready, willing, and able has the disposition to participate in the mentoring relationship to learn by applying guidance offered to them. These dispositions are fundamental internal resources that are the context for their learning and development within the mentor-mentee relationship. These internal resources, coupled with emotional intelligence and self-awareness, equip the mentee with social-emotional skills to initiate and sustain mentoring relationships, to solve problems with efficacy (Bandura, 1997), and to hold a growth mindset (Dweck, 2007).

The mentee who self-regulates their motivation and actions (Shunk & Zimmerman, 1998) sets goals, works to attain those goals, incorporates feedback along the way, and makes adjustments for goal attainment. The third section of this chapter describes how to structure mentoring programs to promote self-directed mentees.

Mentoring Program Structure to Promote Self-Directed Mentees

The mentoring program structure can promote or thwart a mentee’s self-directedness. Program structures include the policies, procedures, expectations, cycles of activity, and relationship-building strategies. Specifically, the mentoring program structure should provide to mentees: (a) the program’s purpose and objectives, (b) the rationale for and benefits of engaging in the mentoring relationship, (c) program and mentor expectations, and (d) examples of self-directed behaviors.

But how can mentor program directors incorporate the above provisions into the mentoring program? They can ground all aspects of program structure and delivery in autonomy-supportive instruction (ASI) (Jang et al., 2010). ASI is a set of six strategies that builds relationships, promotes autonomy, and develops competence. ASI is well-researched and empirically validates that learner engagement is promoted when intrinsic motivational resources are supported.

In autonomy-supportive mentoring programs, program structures and relational practices intentionally encourage mentee intrinsic motivation, help mentees set and reach goals, and support self-regulated and self-determined behavior, all of which ultimately develop self-directedness. In developmental mentoring relationships, mentees see themselves as learners. As previously described in Figure 11.2, intrinsically motivated actions are based on awareness, interests, and inherent satisfaction. In short, self-directed mentees want to learn and grow and they apply effort to activate their motivation for success.

The first subsection in this portion of the chapter, Using ASI in Mentoring Programs and Practices, explains ways to use ASI in mentoring programs and practices; includes a table of ASI strategies and their operationalized mentor behaviors; and describes how to use ASI to promote engagement in mentoring program activities, build mentee initiative, and respond to mentee emerging competence. The second subsection, Program Expectations Aligned to Self-Directed Learning Activities, aligns ASI strategies with program expectations and self-directed learning activities. The third subsection, Promote Self-Directedness with ASI Mentoring Program Structures, describes how ASI mentoring program structures promote self-directedness. And the fourth subsection, Using ASI to Develop Mentor Program Assessment Strategies, provides suggestions for how to use ASI to develop program assessment strategies that are aligned to an ASI-based mentoring program’s structures for building relationships and competence, and it includes a table of suggested quantitative and qualitative measures.

Using ASI in Mentoring Programs and Practices

In this subsection, I will first explain the six ASI strategies and how they were operationalized for mentoring programs; second, describe training environments that are highly interactive; third, describe developing the mentee’s efficacy for success; and I conclude with suggestions to intentionally activate mentee self-directedness.

The Six ASI Strategies

ASI is comprised of three relational strategies and three competence-building strategies that have been shown to positively impact learner engagement in many learning environments, for example, in K–12 education, higher education, language learning, sports, health management, nursing training, and business or corporate environments (Center for Self-Determination Theory, 2022).

To date, it appears that I have been the only person to apply ASI to mentoring programs, and I have found effective outcomes thus far (Clabaugh, 2013, 2020). These publications describe how ASI strategies were enacted within program structure, training, and mentor-mentee pairings, which advances our understanding of the impact of ASI beyond teacher-student, coach-athlete, manager-employee, health provider-patient, and parent-child pairings.

Each ASI strategy on the left of Table 11.1 promotes either belonging or competence and is operationalized as a set of behaviors (Reeve & Jang, 2006). ASI strategies can be successfully trained (Reeve & Halusic, 2009), practiced, and assessed. In one of my ASI-based mentoring programs, one assessment outcome was an ASI vernacular specific to the mentoring program. This vernacular was used to operationalize ASI strategies within the mentor-mentee relationship.

Table 11.1

Autonomy Supportive Instruction (ASI) Strategies and Operationalized Behaviors

| ASI strategy | Operationalized mentor behaviors |

|---|---|

| Mentor nurtures the mentee’s inner motivational resources (belonging) |

Shows interest in and enjoyment of mentee response and work

Identifies and supports mentee needs, interests, and preferences

Provides time to work on program tasks and act on requests

Provides encouragement that boosts program engagement

Provides challenge by asking mentoring program questions Provides opportunities to take initiative for using tools, resources, strategies, and skills to meet mentor goals

|

| Mentor uses supportive and informational language (belonging) |

Provide information that connects mentee context goals and content

Affirms mentee competence and success

Explains why mentee is doing well and making progress

Promotes value by providing rationale for task usefulness

Promotes importance of mentoring program activities

|

| Mentor acknowledges and accepts mentee’s positive and negative learner affect (belonging) |

Responds affirmingly to mentee perspectives and ideas

Treats mentee complaints as a valid reaction

Treats mentee resistance as a valid reaction

|

| Mentor provides clear and detailed instructions (competence) |

Mentee clearly knows what to do

Instructions are well organized

Information frames upcoming mentoring program activities

|

| Mentor provides strong guidance (competence |

Demonstrates leadership in the mentoring relationship

Offers a clear action plan to meet mentee goals

Gives hints and tips for mentee success

Mentee goals and responsibilities are clearly and positively stated

|

| Mentor provides informational feedback (competence) |

Suggests skill-building actions, tools, or strategies

Gives instructive statements to increase mentee knowledge

Gives statements using positive and affirming phrases

Statements promote mentee understanding and competence

|

To apply ASI during mentoring programs, the structure must provide opportunities for mentors and mentees to apply initiative during program activities. The rationale for this is that mentors directly experience ASI as a learner and then use competence and efficacy to model and intentionally apply ASI with mentees. Before the program begins, mentors need to be trained, observed, and assessed in ways that apply ASI strategies to their learning and practicing of ASI strategies. Thus, mentors are learners who experience the relational elements of ASI situated in a mentoring relationship. This contextual learning environment helps mentors develop efficacy for applying ASI strategies with mentees.

Program directors also need training and mentoring to learn why and how to use ASI and are then assessed to demonstrate their capacity to effectively and confidently model and apply ASI with mentors during training and orientation, with program communication and documents, and during program assessment. In this way, the program manager becomes a meta-mentor for mentors; mentors who are mentored and assessed by the meta-mentor will be prepared to efficaciously model and apply ASI with their mentees. The program manager as meta-mentor must be able to describe the value and relevance of ASI to the mentors and model ASI strategies as intentional exemplars.

Therefore, all aspects of the mentoring program are grounded in ASI strategies: training and orientation, invitations and communication, program structure and delivery; mentoring program activities, policies, and procedures; mentee assessment and feedback; program assessment items and assessment protocols; and recommendations for program improvement. For example, to promote intrinsic motivation, engagement, and self-directedness when providing program overviews, invitations to participate, and describing program activities, program directors apply the strategies of using supportive and informational language and providing clear and detailed instructions.

A mentor uses ASI to promote their mentee’s intrinsic motivation for taking initiative during program activities by applying the strategies of nurturing inner motivational recourses and acknowledging and accepting positive and negative affect. How a mentor responds to their mentee’s level of success can develop competence when they apply the strategies of providing strong guidance and providing informational feedback. The next section unpacks each of these examples by describing how and why each ASI strategy can be applied.

How to Use ASI to Promote Engagement With Mentoring Program Activities

The program director introduces mentors and mentees to ASI and mentoring program components in a training (mentors) and an orientation (mentees) that is delivered using ASI strategies. The ASI strategy of using supportive and informational language promotes belonging, so use this strategy intentionally when writing program invitations, when designing the training agenda, and when facilitating orientation and initial mentor trainings.

ASI phrasing is inclusive, welcoming, and clearly stated without being threatening. The second phrasing is controlling and transactional, and it assumes that people need to be directed or they will not comply. For example, the orientation email uses ASI phrasing such as, “We are looking forward to your attendance at this important orientation. Remember, mentees who attend will be able to . . .” instead of saying, “You must attend this mandatory orientation. Mentees who don’t attend will not be able to . . . .” This second phrase also presents a punishment (“if you don’t attend you won’t get to . . .”), which appeals to lower levels of extrinsic motivation. Trying to motivate people at lower levels than they naturally have for the program can create feelings of condescension and low trust.

During mentor training, describe mentor and mentee roles and mentee expectations, and walk through the program calendar and activities using the strategy of providing clear and detailed instructions to build mentor competence for knowing what is expected of them. Present the information in a logical sequence, from broad to more specific. Clearly identify the tasks mentors and mentees need to do and when to do them, for example, “First, complete this application, then fill out this intake form before your first meeting so that there is time to review your information and formulate your first meeting agenda.” After providing clear directions, mentors and mentees know what to do, why, and what the benefit is to them. After this explanation, walk through the actual application and forms.

The goal is to provide clear instructions that are well organized and are provided in the same sequence as the set of tasks to complete. Importantly, this protocol gives participants (mentors in a training, mentees in an orientation) immediate ASI strategy exemplars that can be discussed later between mentors and offers incidental learning opportunities about how ASI can be used in multiple circumstances. Administering a short interactive summative assessment next would provide feedback to the participants and program director on how well they are grasping the information while providing opportunities for participants to build relationships with each other.

A training environment that is highly interactive includes multiple opportunities for relationship building and contextual sharing. Each interaction sets the stage for participants to build relationships, engage in the program, and build competence for their roles and the roles of others in the program. For example, there could be a 4-minute partner recap, where each partner in a pair of participants has 30 seconds to state their name and a hobby and describe the paperwork, due dates, and benefits of following through.

How to Use ASI in Mentor Responses to Build Mentee Initiative During Program Activities

During program activities, using the strategy of nurturing inner motivational recourses to promote participant belonging, initiative, goal setting, and follow-through. Mentors find opportunities to show interest in what their mentees are doing by asking open-ended questions in a conversational tone: “How did that conference go last week?” Mentors listen to mentee responses so they can identify their mentee’s needs and preferences, and then connect those needs and preferences to upcoming program activities. For example, if the mentee enjoyed the conference, ask them for examples about what they enjoyed, then identify topics of interest to them. The mentor can then provide information on the topics the mentee found interesting, link them to upcoming opportunities for taking initiative, and then comment on the mentee’s ongoing engagement.

Sometimes things do not go well; mentors and mentees need trust to build confidence in the program staff, activities, and outcomes. There should be enough trust for mentors to confide in program directors and for mentees to confide in mentors so they feel comfortable sharing stressors and negative impacts on their progress. In these situations, apply the ASI strategy of acknowledging and accepting positive and negative affect to develop belonging and efficacy for building knowledge and skills over time. Self-directed mentees use volition to set meaningful goals, so the mentor takes an affirming approach in response to mentee frustration. The mentor listens thoughtfully and becomes trusted and respected. A mentee’s frustrations and difficulties are heard as valid and important to the mentor, and the mentee develops awareness of their own process and progress (Bray-Clark & Bates, 2003), which can reduce negative self-talk.

The intention here is to develop the mentee’s efficacy for success even when things seem to go wrong and be reminded that learning happens when taking risks to try new things. In times when the mentee seems to resist a suggestion, the mentor not only knows what interests the mentee has but also knows what motivates them. Coupling interests and motivators is a way to break through resistance and demonstrates that the mentor is “in their corner” and sees the mentee as capable. The mentee uses internal motivation when there is congruence between their identity as a learner, in the absence of negative consequences for not yet succeeding. Ultimately, mentees activate intrinsic motivation because they are interested in meeting their goals in partnership with their mentor.

How to Use ASI in Response to a Mentee’s Emerging Competence

Self-directed mentees want to impact their professional development by meeting their goals, applying more successful tools and strategies, and finding new approaches to make progress. The mentor can provide strong guidance to build mentee competence by modeling decision-making and problem-solving strategies and by sharing their own stories of success over time. Mentors who describe their developmental processes give the mentee vicarious learning experiences that includes clear action plans, hints, and tips.

For example, if the mentee has a publication goal for next semester, the mentor can recount their process for developing their first successful manuscript and then help the mentee develop a clear action plan. The mentor provides hints and tips from their experiences, couched as “if I knew then what I know now” scenarios, which helps the mentor identify realistic goals and responsibilities for themselves. The mentor also uses positive phrasing such as, “Remember to . . .” rather than “You better not forget to . . .” and “You can expect a few set-backs, and you have some strategies to use when these happen” instead of “It never works out like you planned, but oh well, get used to that.”

Not all people relate to feedback in the same way. Some mentees need more time and practice to process and then implement feedback because they have had experiences with controlling, condemning, or ineffective feedback. Informational feedback can be used with the intention to develop rather than correct, and it provides resources for success rather than highlighting skill deficits that should be “turned around.” Providing informational feedback develops competence, efficacy, resilience, and a growth mindset (“not yet” thinking), which leads to self-determined behavior changes.

For example, if a mentee writes their draft manuscript for publication, and when reviewing it, the mentor notices several organizational issues. The mentor identifies what is and is not working with the manuscript organization (where the draft flows and where it gets off track, where the voice is consistent, and where it changes). Rather than focus on what is not working, the ASI mentor leverages what is working to illustrate where the draft falls short.

This feedback can be worded as “The first two sections flow well because they are organized chronologically, and a reader can easily identify change in the historical significance over time. I suggest you write the third and fourth sections chronologically too, so that they flow just as smoothly.” This suggests a skill-building strategy, is instructive, and is stated in an affirming way. There is room for the self-directed mentee to ask clarifying questions, brainstorm some suggested revisions, or try a brief revision to determine whether they are getting the hoped-for result.

Useful feedback is actionable and acknowledges effort while promoting progress and success. However, informational feedback goes further—it is delivered with intention to promote the mentee’s understanding and competence while practicing new skills. Mentors want their self-directed mentees to have a clear idea of what to do next, to know what tools and resources they can apply, and to set feasible goals for themselves. The bottom line here is that a self-directed mentee will want to use volition and initiative to follow their mentor’s suggestions to develop new skills or apply new tools and strategies.

This section has described mentoring programs that, when delivered via ASI strategies, promote the development of self-directed mentees who are ready, willing, and able to apply intrinsic motivation, determination, and regulation to engage in mentoring program activities to meet their goals. There is an exciting opportunity to improve mentoring as a field by increasing the quality of mentoring programs and mentor-mentee relationships that lead to improved mentee outcomes. Additionally, there is a gap in the ASI literature for describing how ASI contributes to the use and benefits of mentoring success so that program directors and mentors can begin to form schema for using ASI to promote relationships with their mentees in ways that develop self-directedness and engagement for mentee success.

As an additional take-away, I used ASI strategies to write this chapter in order to promote reader engagement with this information, and to encourage readers to use intrinsic motivation to develop mentoring programs that incorporate ASI. For example, clear and informative phrasing conveys how mentoring program directors can apply ASI to create a mentoring program that develops self-directed mentees. Also, I phrased information positively, and used details to offer my rationale for using ASI to promote mentor-mentee developmental relationships. Writing the chapter in this way “walks the ASI talk and talks the ASI walk” for readers to model ASI in action. Just as this content is meant to encourage and expect your self-directedness as a reader, ASI mentoring program expectations include intentional development of self-directed mentees by embedding specific learning activities into the mentoring program.

Program Expectations Aligned to Self-Directed Learning Activities

Mentoring program directors can use ASI themselves to ensure the mentors know and apply ASI in mentoring relationships. Program directors can intentionally design the program and promote the same expectations of their mentors that mentors are expected to have for their mentees. In this way, the program structure invites both mentors and mentees to be self-directed.

This section outlines a series of mentoring program expectations and describes how each can be presented as self-directed opportunities, followed by suggestions for relevant learning activities that the mentor can facilitate using ASI strategies. Structurally, the mentoring program needs to match its audience’s context. For example, a faculty-mentoring program may have a late-summer orientation, fall semester and spring semester activities, and a closing evening scheduled near commencement. In contrast, a staff or administrator mentoring program does not need to be tied to the academic calendar.

In general, an ASI-based mentor program has three phases: program development, mentor development, and mentor-mentee orientation, followed by a series of mentor-mentee program activities. The program-development phase is used to consider the program’s needs and purpose, determine the desired mentor and mentee outcomes, and explore ways to select and train mentors in ASI and orient mentees to the program. Then the program is developed and marketed, and all program materials are created and produced.

During the mentor development phase, the mentors are selected, trained in ASI and relational mentoring strategies, and given structured opportunities to practice and then reflect on their role and use of ASI as mentors. Then, mentors who continue in the program are oriented to program expectations, procedures, and relevant aspects of the specific mentoring program. If several mentoring programs are being developed, the development and mentor training phases can be conducted as a whole; then, mentors can separate into departments or cohorts based on their specific areas of mentoring.

The mentor-mentee orientation and program activities are grounded in ASI to develop self-directed participants. As described earlier, mentors experience ASI in their training and program development phases so they have direct experience from which to apply ASI as a mentor. The orientation typically starts with a welcome and introductions that include personal and professional information and apply the ASI strategies that promote belonging. The program purpose and expectations are clearly presented, and time is provided for mentees to ask questions for clarification and understanding, which activate mentee initiative and help-seeking.

Program materials and activities are first overviewed and then discussed in smaller groups to facilitate relationship-building, efficacy, and competence with the program content and resources. Facilitating interactive activities during the orientation models and validates the benefits of relationship-building between the mentees as a cohort, and between mentor-mentee pairs. Mentees appreciate knowing who their mentor is toward the end of the orientation, after they have had opportunities to interact with mentors as a group. Regardless of how mentor-mentee pairs are matched, providing some time during the orientation for each mentor-mentee pair to get acquainted is important. This can be semistructured or a free-flowing conversation. The orientation ends in an upbeat, positive way and with a sense of optimism and excitement for the program and mentor and mentee growth.

The program sequence of mentor-mentee activities advances the mentor-mentee relationship over time and promotes the mentee’s progress toward their goals. Mentors are expected to help develop this sequence because they are content experts and have insights and experiences for best practices. One size does not fit all, so mentors must use an emergent curriculum (Jones & Nimmo, 1994) approach during program activities in response to fluctuations in their mentee’s engagement, learning pace, and success. Emergent curriculum is described as learning activities that are modified and shaped to meet learner needs in ways that integrate learner interests into the learning environment.

Mentor curricular decisions are responsive and tailored to their mentee’s learning style and individual needs. In combination with ASI, emergent curricular approaches give mentors two powerful tools to ensure mentee engagement and success. During mentoring activities, mentors use ASI to explore how their mentee’s past experiences impact their current role and learning. Mentors view the mentee as a self-directed and autonomous learner and respond in ways that assume competence and engagement. Each mentee enters the program with their own funds of knowledge, which requires an individualized mentee curricula. The mentee makes progress based on the mentor’s observations and suggestions as well as the mentee’s dispositions for learning and overall engagement.

When the mentee appears to want reassurance or specific direction, this may indicate they have lower experience, efficacy, and/or confidence than anticipated and may need more structure and guidance. The mentor intentionally applies ASI strategies to be responsive and supportive. They share their own experiences and learning as one approach to provide options and choices for the mentee. Mentors may invite the mentee to talk about past learning and goal attainment from other settings. Mentors may suggest the mentee talk with other people or coworkers as resources for ideas and strategies to meet their goals. These responses are examples of three ASI strategies: Providing strong guidance, providing informational feedback, and nurturing inner motivational resources.

Sometimes mentees demonstrate resistance, which indicates they may not have confidence in themselves or goal attainment. The mentor may consult with the program director first to broaden their perspective before meeting with the mentee to understand the mentee’s context and perspectives. The mentor uses active listening techniques and applies the ASI strategies of accepting negative affect by concurring with the mentee’s perspective and nurturing inner motivational resources by asking clarifying questions for deeper understanding that shows interest in the mentee’s past experiences and how those experiences inform their perspective.

After mentoring program directors have determined their program expectations and mentee self-directed learning activities, the program director aligns these expectations and activities to the mentoring program structure. As mentioned earlier in this chapter, autonomy is thwarted in controlling situations because choices are not encouraged or relationships are more transactional. Likewise, the program procedures, policies, and practices need to be developed so that they promote self-directedness. The next section provides a mentoring program blueprint for developing mentee self-directedness within the mentoring program structure.

Promote Self-Directedness With ASI Mentoring Program Structures

The mentor can use reflective practice (Kolb, 1984) or critical reflection (Fook, 2015) to explore the mentee’s context and needs, discuss possible approaches, and collaboratively determine next steps. The mentor may have an opportunity to provide informational feedback when the mentee seems ready to accept the mentor’s suggestions and perspective, which may differ from the mentee’s.

This subsection describes how the mentoring program structure promotes self-directed mentees knowing that transactional conversations thwart motivation and self-regulation, while autonomy-supportive conversations activate intrinsic motivation, self-regulation, and self-determination—all of which promote self-directedness. ASI strategies promote engagement at higher motivational levels, which activates the mentee’s interest and competence in becoming self-directed. The six ASI strategies and their operationalized behaviors (see Table 11.1) are intentionally employed to set a mentee’s stage for their engagement, relationship, and self-motivated learning when the program structure is grounded in ASI strategies.

Additionally, mentors take an emergent approach to developing curricula for their mentees and building trust and respect through intentional relational exchanges. Mentors show interest in their mentee, mentors develop the competence of their mentee, and mentors promote their mentee’s goal attainment. When developing the program training, orientation, and materials, ASI strategies are used during facilitation, mentor training, and mentor-mentee interactions. Program managers and mentors need to be well-prepared to use ASI so that mentees can successfully be self-directed to meet their goals and succeed.

To determine how well your program structure promotes self-directedness and to engage in ongoing program improvement, assessment strategies must be developed during the program-development phase. The process for designing assessment, as well as the types of and specific assessment items, and the assessment cycle can be grounded in self-determination theory and ASI. In the next subsection, I explain the value of aligning program assessment strategies with ASI. Grounding program assessment in ASI’s principles of autonomy, belonging, and competence ensures that the mentoring program’s expectations and practices uphold an autonomy-supportive culture overall.

Using ASI to Develop Mentor Program Assessment Strategies

Program assessment strategies that use various tools and measures to collect different data types can be validated to ensure reliability within an authentic assessment protocol. The assessment strategy was developed and administered using ASI strategies, which increased participants’ sense of congruence across mentoring program activities that were inclusive and relational. Authentic assessment results described individual success, mentor-mentee pair success, cohort success, and overall program success to inform continuous improvement.

Program assessment included quantitative and qualitative measures collected from individuals and a focus group each semester. Quantitative measures included Likert scale items for mentors and mentees on student evaluation forms that rated mentor effectiveness, mentee engagement, and mentee self-directedness, as well as overall instructional satisfaction. Qualitative measures were ASI observations made by the program director and mentors, open-ended items for individual and group perspectives and examples of ASI that were collected from program directors and mentors, mentor evaluations of mentee success, and mentee evaluations of mentor and program success. Items collected in focus groups assessed mentor and mentee perspectives, testimonials, and suggestions for improvement.

These data were analyzed to describe program effectiveness, identify mentors’, mentees’, and students’ satisfaction and success, and to identify relational elements of mentoring, levels of engagement and self-directedness, and suggestions for improvement. These data were analyzed across subgroups of mentors compared to mentees, in mentor-mentee pairs compared to past pairs, and by program cohorts compared over time. Results informed program improvement in structure, training, and materials. The purpose of the quantitative items was to collect role-specific program ratings and the purpose of the qualitative items was to collect spontaneous perspectives and suggestions for improvement. Table 11.2 provides suggestions for program assessment items to measure in both categories.

Table 11.2

Suggested Quantitative and Qualitative Assessment Measures

| Suggested quantitative measures | Suggested qualitative measures |

|---|---|

|

|

Focus groups invite the cohort of mentors and mentees to meet with the program director at the mid-point and end of the program to share program experiences and suggestions. Mentors and mentees were asked to describe how they used ASI and about the impact of ASI strategies on mentee motivation, engagement, and directedness. Mentees heard other mentees’ impressions about participating in the program. Mentors heard how other mentee-mentor pairs experienced being in a mentoring relationship.

Focus groups facilitated using ASI strategies elicit honest and candid conversations through the strategies of accepting negative affect and nurturing inner motivational resources because each of these strategies builds relationships, trust, and respect. Mentors and mentees can also engage in reflective conversations about the impact of ASI strategies across mentor-mentee pairs. There are multiple ways to implement ASI, and each mentee has differing needs, so these were often lively conversations yielding insights into ASI’s contribution to program success.

Focus group data informs what needs were and were not met for mentors and mentees and helps the program director understand mentor competence with ASI and mentee efficacy for goal attainment. Focus group data combined with individual qualitative and quantitative results can be analyzed for themes, trends, and program improvement suggestions. Results are used to identify and describe evidence of program effectiveness and inform upcoming training and related materials. For grant-funded mentoring programs, a comprehensive and integrated assessment protocol provides evidence and levels of mentee success, supports claims of program effectiveness, and verifies of continued improvement over time.

Findings and Recommendations

In this fourth and closing section, I present findings generalized from my 8 years of facilitating ASI-based mentoring program. Overall, when ASI was used over time and became a valuable element in the mentoring program structure and culture, there were benefits to mentors and mentees. Following these findings are a set of recommendations to consider for your own program’s success. These findings and recommendations are designed to inspire you and get you thinking about learning how to develop and implement an ASI-based mentoring program.

Generalized Findings

Mentors indicated that their mentees became more self-directed over time, based on how and when they engaged and took the initiative to meet their goals. Mentees reported that they experienced and understood how and why the mentoring relationship with embedded ASI strategies promoted their engagement and self-directedness. Mentees also said they wanted to learn about and apply ASI strategies in their teaching and professional interactions.

A major theme across several mentor program cohorts was that being involved in an ASI-based mentoring program was an integrated experience of personal and professional significance. Mentees’ intrinsic motivation was activated more frequently, and they took increasing levels of initiative for their learning and goal attainment. They stepped up to the plate and became more ready, willing, and able to exceed program expectations, and thus made more progress and had more success.

Recommendations

The value of using ASI as a foundation for mentoring within a mentoring program to model and promote autonomous self-directed mentees relies on the mentors being self-directed and on program structures that model and promote self-directedness. Future research on mentoring programs that are not successful or cannot be sustained could assess mentor-mentee engagement levels, implement ASI strategies for 2 years, and then remeasure engagement levels.

Suppose mentors and mentees are struggling to engage. In that case, I recommend assessing the levels of controlling behavior versus autonomy supportiveness within the mentoring program structure and the mentor-mentee relationships. Next, I recommend incorporating ASI to revitalize the program structure by training program directors and mentors and then helping them develop their new program with clear outcomes, expectations, structures, and supports.

Looking at current research on the environments in which ASI is applied, it seems that no college faculty mentoring programs are represented. This may be because no one else is using ASI in higher education mentoring or because mentoring programs embedded with ASI are happening but information about them is not being published. Given the ASI literature’s focus on K–12 education, management, sports, and health care, I recommend that many more ASI-based mentoring programs be developed, enjoyed, assessed, then described in the ASI and the mentoring literature.

After all, a well-structured mentoring program that integrates ASI as a method and an expected outcome can transparently “walk its talk and talk its walk” while promoting mentees’ self-directedness and opportunities to use volition and agency to sustain their engagement and self-regulation. Mentees learn more effectively through intrinsically motivated participation because their needs for belonging, autonomy, and competence are satisfied. Mentees used self-directedness and self-determination to engage fully and deeply across the program’s activities and, ultimately, meet their goals for advancement and growth.

Overall, I suggest that mentors and program directors observe, assess, confirm, and track mentee demonstrations of motivation and regulation levels across program activities. I suggest that program directors intentionally create opportunities to assess a person’s motivation level for a task early in the program. Over time, opportunities for mentees to develop and demonstrate self-directedness should be promoted through written, spoken, and interactive communication. When a mentee is more self-directed, they are more intrinsically motivated, prepared to engage, and more likely to succeed. Mentors can then intentionally promote their mentee’s self-directedness, creating a mentoring relationship with a personalized context for mentee learning and development.

References

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Freeman.

Bray-Clark, N., & Bates, R. (2003). Self-efficacy beliefs and teacher effectiveness: Implications for professional development. The Professional Educator, 26(1), 14–22.

Bredekamp, S., & Copple, C. (2009). Developmentally appropriate practice. National Association for the Education of Young Children.