8 Outlining the Goals, Objectives, and Outcomes of the Mentoring Program

Lisa Z. Fain and Jamie Crites

Abstract

Even when institutions already have a mentoring culture, a mentoring program is not an end in itself. Rather, mentoring is a tool to achieve a broader outcome, be it at the institutional, department, or individual level. While these outcomes may vary, it is critical that a mentoring program is carefully crafted in service of the outcomes. It must meet the needs and objectives of not only the mentees and mentors but also the institutions and the field. In this chapter, authors Lisa Fain and Jamie Crites will use a case study to discuss how to craft goals, and objectives that are aligned to meet desired outcomes. We will explain how consideration of seven design elements will determine and reach the goals, objectives, and outcomes of programs. Lastly, utilizing a logic model we will guide you through how to employ this framework to appeal to multiple key stakeholders at your institutions.

Correspondence and questions about this chapter should be sent to the first author – lfain@centerformentoring.com

Acknowledgements

With gratitude to: Michelle Hancock for her assistance with graphic design, Lois Zachary for her guidance and thought leadership, and our clients at Center for Mentoring Excellence, for helping us learn the lesson that “the main thing is keeping the main thing as the main thing.”

Introduction

Tayshia has been a program coordinator for the business school at her university for 5 years. The majority of the students who enter the graduate program are first-generation graduate students. Over the years, she has noticed a lack of meaningful connections between the advisors and graduate students. Also, the students complain that they receive no guidance for navigating the processes and procedures at the school. For example, graduate students frequently ask how to write grant proposals, what it takes to become a professor, what other schools do, and why they should stay in their current program. While Tayshia has a list of resources she can pass along, she suspects that students would benefit more from the connection and learning that a mentor could provide. She reaches out to her supervisor and asks if they would consider implementing some sort of initiative to better support the graduate students. Her supervisor says, “Yes, that sounds great! Present your proposal to us at our next budget meeting.”

Tayshia begins her task by conducting a needs assessment—discussed in Chapter 5—to determine if the issues she is noticing are truly problematic to the success of the graduate program. Upon completing the needs assessment, she notices that the business school is struggling to retain graduate students, and students perceive that the program lacks a commitment to teaching them about education systems like the internal review board process, grant writing, and effective student teaching. To address this problem, Tayshia has decided to propose a mentoring initiative.

As practitioners in the mentoring space, we often see organizations launch a mentoring initiative without taking the time to think through outcomes, goals, and objectives. When this happens, even if the mentoring pairs are highly satisfied and the program is well regarded by participants, the programs have limited longevity because there is no integration beyond its participants and coordinators, and no institutional (see Chapter 6) investment in its success. Therefore, to design an effective program, it is critical at the outset to identify desired outcomes, articulate goals that align with the outcome, and objectives that align with the goals.

Tayshia’s success rests foremost on her ability to achieve her desired outcome of supporting graduate students and on her ability to achieve her goal of creating a mentoring initiative. Using Tayshia’s story, we explore how to determine and align the goals, objectives, and outcomes of a mentoring program. Next, we will demonstrate how to align goals, objectives, and outcomes through the utilization of a logic model. We will then provide seven key design elements to consider while designing a mentoring initiative. We conclude this chapter by demonstrating how these design elements can fit into a logic model that you can use to inform your stakeholders of the goals, objectives, and outcomes of your program.

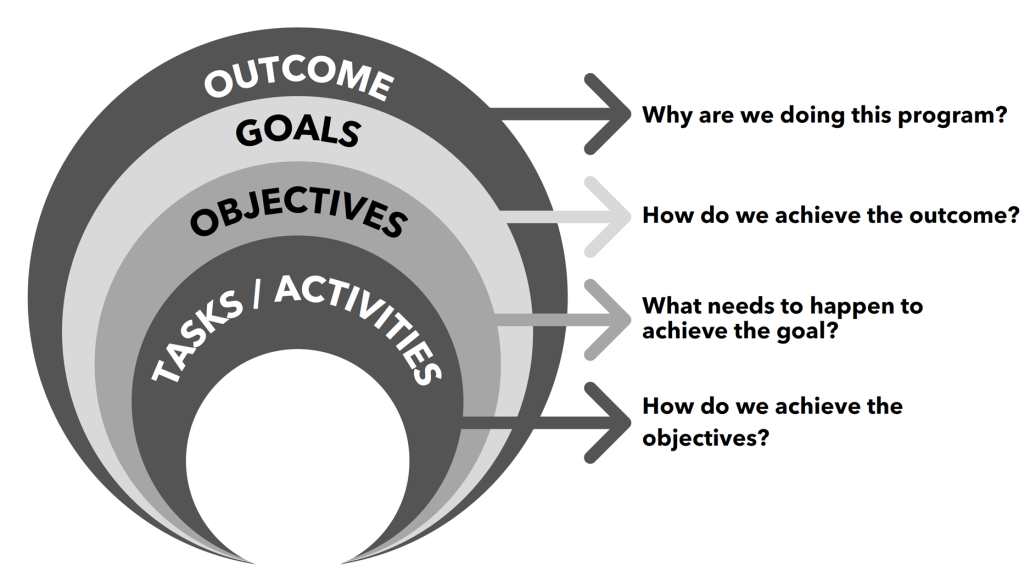

Figure 8.1

Model of Outcomes, Goals, Objectives, and Activities

Outcomes An outcome is an overall change you seek to achieve as a result of your efforts. It answers the question, “Why are we doing this?” and likely will derive from a needs assessment. The outcomes of the program or initiative are also used in the development of a logic model to illustrate the flow from resources to outcomes and will discuss in future sections. The outcome should be something that advances a core mission, vision, or value of the organization. While the positive impacts of mentoring are well-established (see Chapter 4), mentoring itself is not an outcome. The outcome is what you hope to achieve by implementing a mentoring program. Some examples of demonstrated outcomes from mentoring programs are more program satisfaction, greater networking skills, enhanced connection to the institution, and greater job satisfaction (Allen et al., 2004).An outcome may be short-term, intermediate, or long-term and is demonstrated by changes in knowledge, beliefs, or behavior (Israel, 2001). A short-term outcome is likely the easiest outcome to develop. These outcomes should be noticeable at the completion of the first cohort of mentees and mentors and should be demonstrable by changes in knowledge, skills, abilities, or attitudes. For example, Tayshia may choose to make a short-term goal like, “By the end of the mentoring period, mentees will have an increase in self-efficacy regarding education systems.” Short-term outcomes can also be relatively simple: number of participants, program satisfaction, and number of meetings. Having short-term outcomes like these can aid in the evaluation and revision of the program (Hatry, 1999).

An intermediate outcome should center around adoption of the mentoring program. This may take months or years, depending on the length of the program. For Tayshia’s program, the department or graduate program has recognized the value of the initiative and is energized about the contribution it adds for the students. Thus, she may have an intermediate outcome such as, “The mentoring program is a point of attraction for incoming students, as measured by the incoming students survey item, ‘what attracted you to the program?’”

Long-term outcomes are also referred to as impacts. These may be measurable well into the future and should represent a significant social or cultural change in the program or institution as a result of the mentoring program. For instance, the long-term outcome for Tayshia’s program could be, “The university’s administration will adopt the mentoring program to be implemented across all graduate programs at the university” or “The business school has embraced a mentoring culture.”

Goals Unlike the individual goals we often ask our mentoring partners to establish, program goals are broad, overarching statements that propose a program, project, or initiative. The goals are a necessary step that connects to the mission and vision of the broader program or institution. More than one goal may emerge. These goals need not be identical; they merely need to be congruent and should answer the question, “how will we achieve the outcome?” The goal statement you craft for the program must align with that vision to ensure that the program is a sustainable initiative that will survive beyond the creation of the program. The goal should be specific and measurable and will likely have several objectives within the goal statement. For example, Tayshia’s goal could be, “Create a mentoring initiative for graduate students in their second year,” “Utilize peer mentoring circles for first-year students,” or it could be a goal unrelated to mentoring altogether, such as, “Provide counseling for graduate students in the program.”

Objectives and Activities Next, we add another level of detail and establish the program objectives. The objective answers the question, “What needs to happen to achieve the goal?” At this stage, we begin to determine the metrics by which we will judge a program’s success. A program objective is a concrete, performance-based statement that you will use to measure the success of the program. When developing the objectives, decide upon a timeframe and list any available resources that are available for the mentoring initiative (e.g., learning platforms, video conferencing, literature, matching tools, etc.). After establishing the timeframe and resources, map out specific mentoring program results that fit within the goal. When considering the specificity of the objectives, be mindful of how they will be measured. Measuring an objective can take many different forms, ranging from a quantitative survey to several conversations with participants. For example, if our goal was to provide our graduate students with a competitive advantage over their peers at other institutions, our program objectives could be measured by GPA, class attendance, an objective prementoring and postmentoring assessment, or retention rates.

For each objective, there will be one or more activities. These are tasks you will need to accomplish to reach your objective. Together, these activities will populate a project list or to-do list. Tracking activities can be useful for accountability and momentum. Assuredly, incorporate activities and tasks that will ultimately align with the program goals and objectives.

Crafting the Mentoring Initiative Outcomes Let us consider the story of Tayshia at the beginning of the chapter. Tayshia started developing her proposal by considering the goals and desired outcomes of the program. She starts by checking in with the literature.

Articulating Outcomes and Goals

Mentoring can serve many purposes, and there is ample research to support a myriad of benefits. While most mentoring research has evaluated outcomes of mentoring for mentees, there is also evidence to support that both mentors and mentees benefit from mentoring (Allen, 2003). For both mentees and mentors, there are subjective and objective outcomes that positively correlate with mentoring (Underhill, 2006). The following sections are examples of benefits for mentees, mentors, and organizations. These benefits are not exhaustive and the relevance of each will vary depending on the intended outcomes of your specific mentoring program.

Benefits for Mentees

Generally, mentees have experienced outcomes like an increase in income, the number of promotions, and career advancement opportunities (Underhill, 2006; Allen et al., 2004). More specifically, in a study from Harvard Business Review, 84% of CEOs reported that as a result of mentoring, they were better able to avoid costly mistakes and become proficient in their roles at a quicker pace, and 68% of CEOs made better decisions (De Janasz & Peiperl, 2015). Moreover, a 5-year study of 1,000 employees revealed that 25% of employees who participated in a formal mentoring program gained a salary-grade change and were promoted five times more often than those without a mentor (Gartner Research, 2006).

Mentees experience an increase in job and career satisfaction, career commitment, as well as a stronger intention to stay, career commitment, and more perceived promotion opportunities (Allen et al., 2004; Underhill, 2006). We can tie these outcomes to the development of a mentor program. For example, if the purpose of the mentoring program is to retain students or first-year professors, then consider constructs like employee satisfaction, employee engagement, or retention. In one study, 9 in 10 people who have a mentor said that they are satisfied in their current job (Wronski & Cohen, 2019). Of those people, 57% indicated that they were “very satisfied” with their job. Specifically related to new hires, mentees reported that they were more successfully socializing with other employees in the organization after being involved in a formal peer mentoring program (Allen et al., 1999).

Benefits for Mentors

Mentees are not alone in benefitting from mentoring programs. Mentoring is an important developmental component that is heavily emphasized in career and life developmental stages (Kram, 1985; Erickson, 1962). Acting as a mentor allows for reevaluating one’s career and life accomplishments (Levinson et al., 1978). Mentoring also offers the opportunity to celebrate one’s accomplishments and may provide intrinsic satisfaction (Levinson et al., 1978). What is more, mentors tend to have an increase in salary and promotions (Allen et al., 2006), and may experience a boost in subjective career success (Allen et al., 2006).

Organizational Benefits

The institutional benefits of mentoring are also noteworthy. Mentoring programs combat turnover and boost retention. Four in ten employees without a mentor have considered quitting within the past 3 months (Wronski & Cohen, 2019). Moreover, 40% of new managers fail within the first 18 months (Douglas, 2017). However, retention rates for mentees and mentors are about 20% more than for non-mentored employees (Gartner Research, 2006). According to the Association for Talent Development (2012), managers involved in mentoring experience a 64% boost in productivity compared to those who simply train without mentoring.

Diversity, equity, and inclusion are common catalysts for a mentoring program. When comparing mentoring to standard corporate diversity practices (like mandatory diversity training or formal grievance systems), minority representation among managers in the workplace increased between 9% and 24% (Kalev et al., 2006). The same study found that mentoring programs also dramatically improved promotion and retention rates for minorities and women—15% to 38% as compared to non-mentored employees. Regarding generational diversity, millennials who stay in an organization longer than 5 years are twice as likely to have a mentor (Knowledge at Wharton, 2007). Importantly, 60% of college and graduate students list mentoring as a necessity when selecting an employer after graduation (Weiss, 2014). For more on diversity, equity, and inclusion, please see Chapter 12.

Let us return to Tayshia as she seeks to identify her desired outcome. She knows that she wants to see an increase in graduation rates for students from underrepresented populations. Tayshia also considers the research above, and she thinks that given that mentoring programs increase retention rates for new hires and millennials at other organizations, a mentoring program could indeed improve graduation rates for first-generation students at her school as well.

Tayshia considers the desired outcomes as well as the empirical mentoring research. She has narrowed her focus to outcomes for a specific population (first-generation students) to address the long-term outcomes of the larger program (increase graduation rates for students with a minority identity). By operating with this outcome in mind, she can develop a mentoring initiative that is aligned with the desired outcomes of other key stakeholders. Considering outcomes first helps her craft goals and objectives that are relevant, aligned, and effective. If she were to determine the desired outcome after looking at the goals and objectives, she may find herself creating a solution to a problem that does not exist.

Since many of the students who attend the business school are first-generation graduate students, Tayshia has already decided that the long-term outcome she hopes to address is to increase the number of first-generation graduates. Now she must develop an appropriate goal. She considers various initiatives that could lead to more students graduating. Again, Tayshia returns to the research. She investigates what other institutions are doing to support first-generation students, consults the literature, and meets with advisors. She decides to go with a formal traditional mentoring program that will be provided to students during their second year of instruction. At this point, Tayshia has identified outcomes and goals—two of the four components in Figure 8.1. She has added another layer of specificity to her goals by targeting the specific population and initiative that she will use to address her outcome of “increasing the number of first-generation graduate students.”

Extracting Objectives From the Program Goals Next, Tayshia has to identify her program’s objectives. Table 8.1 helps this concept come to life by showing some specific examples of outcomes, goals, objectives, and activities. You can see that the same outcome could have different goals, and the same goals might have different objectives. Tayshia has decided that her desired outcome is to increase graduation rates of first-generation students. After looking at the research and the results of the needs assessment she conducted, she has identified the goal of creating a mentoring initiative for second-year graduate students. Now she examines what objectives she will need to meet to achieve that goal, and she recognizes that she will need to assure alignment and garner support from key stakeholders. She names this as one objective. First, she will need to identify the key stakeholders and meet with them. To measure this objective, she could measure her progress by meeting with a specific number of stakeholders. Once Tayshia has garnered support and her mentoring initiative has been approved, it is time for her to finalize the design of the program and implement the initiative.

Table 8.1

Differentiating and Articulating Outcomes, Goals, Objectives, and Activities

| Outcomes | Goals | Objectives | Activities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Associated question | Why are we doing this? | How do we achieve the outcome? | What needs to happen to achieve the goal? | How do we achieve the objective? |

| Characteristics | Broad statement about what you hope to achieve | Observable and measurable end result, broad in scope, has one or more objective | Steps to achieving the goal-specific results within timeframe and available resources. More specific, easier to measure |

Tasks necessary to achieve the objective |

| Example 1 | Increase graduation rate of first-generation students | Create a mentoring initiative for graduate students in their second year. | Garner support from key stakeholders | Identify the key stakeholders Meet with stakeholders to discuss the proposed mentoring initiative Secure approval |

| Example 2 | Increase graduation rate of first-generation students | Create a mentoring initiative for graduate students in their second year | Recruit mentors | Determine criteria for a good mentor, send out communication to prospective mentors |

| Example 3 | Increase graduation rate of first-generation students | Create a mentoring initiative for graduate students in their second year | Provide mentoring pairs with tools for maintaining a developmental mentoring relationship | Provide a framework for mentoring pairs to use while in their pairing |

| Example 4 | Increase graduation rate of first-generation students | Utilize peer mentoring circles for first-year students | Develop facilitation skills for mentors | Create facilitation skills curriculum |

| Example 5 | Increase graduation rate of first-generation students | Provide counseling (unrelated to mentoring, for example only) | Ensure qualified counselors | Develop and adhere to a list of required qualifications for potential counselors |

Note that when you move from the design phase to implementation, you go from having the mentoring program be the independent variable to the mentee or mentor being the independent variable. For example, remember that Tayshia’s desired outcome is to increase first-generation graduation rates through the mentoring program. To monitor the effectiveness of the program, an objective may be “to increase mentees’ GPA by the end of the year” or “by the end of the mentoring initiative (e.g., 12 months), there will be 100% retention of the students that had a mentor.”

Aligning Outcomes and Goals

A successful mentoring program will align the desired outcomes and goals with the interests of multiple stakeholders in an organization. In launching any initiative, it is helpful to identify who else in the organization might benefit from your desired outcomes; this is likely information you will have garnered from your needs assessment (see Chapter 5). For more on alignment with stakeholders, please refer to Chapter 6.

Once you have learned about the long-term interests of various stakeholders, you can identify outcomes of shared interest and craft a mentoring initiative (the goal) that might help achieve those outcomes. Before you launch the mentoring program, and while still in the design phase, it is critical to meet with other stakeholders to gain alignment, address any objections, and enlist support.[1]

Tools to Align Outcomes and Goals

One of the primary purposes of doing so much work up front is to clarify the line between the goals you have set and the outcomes you seek to achieve. A well-intentioned goal without a connection to the broader strategy of the institution can lead to a program failing or addressing the wrong problem. Using a logic model will help prevent these mistakes. By considering seven key design elements, you will have a holistic approach with adequate variables to map into your model.

Logic Models A logic model can be helpful to ensure that your plans for the mentoring program produce the desired impact. Using logic models can connect resources to both short-term and long-term results while offering a clear visualization of the path or expectations that can be made about a program (Rush & Ogborne, 1996). The development of a logic model creates a roadmap for how the program will be evaluated. It also aids the communication of your plan, goals, and evaluation of the program to the stakeholders who are less interested in theory (Kekahio et al., 2014). Logic models will vary depending on the contextual factors, institutions, program, available resources, staffing, and other factors. Forming a logic model is also an iterative process, where the flow and content of the logic model will shift as more information is revealed throughout the development phase. As such, there is not one specific archetype for a mentoring program logic model. As programs become more complex, so does the model; however, generally, there are four main components to a logic model: inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes. These must be delineated sequentially as they are interdependent.

Figure 8.2

Inputs. The first components of a logic model are the inputs for the program. Inputs are the materials or resources that are available to implement the activities for the mentoring program. Inputs can be tangible resources like budget, learning platforms, or tools, and also include nonmaterial resources like program support, coaching skills, time, or mentoring knowledge. Understanding the scope of inputs will be invaluable when developing the program or communicating the program to stakeholders or new staff members.

Activities. Activities are actions, processes, or events that aid in the achievement of the planned program outcomes. Activities may also be thought of as steps necessary to implement the mentoring program. For instance, mentoring activities could include the matching process, implementation of formal training, utilization of roundtables, e-mail communication, and support or conducting mid-point interviews. Training, matching, and support are three elements of program design that fall into this category.

Outputs. As noted above, activities must be designed to achieve the desired outcomes. To create this link, a logic model utilizes outputs, which are specific measurements that will support the theory of change. Outputs are typically expressed numerically, which may be collected through surveys, research, or aggregated qualitative results. For example, outputs for a mentoring program could be the average number of times mentoring pairs meet, a self-efficacy assessment, or a program satisfaction measure. Outputs align with the measurement consideration above.

Outcomes. The last component of a logic model is the outcomes of the mentoring initiative. Outcomes are discussed at length above. Note that outcomes can be divided into three categories: short-term, intermediate, and impacts (e.g., long-term outcomes). See Figure 8.1 for examples of outcomes in a mentoring initiative.

For a mentoring program, there is an added complexity that should be considered when developing outcomes. For example, there may be disparate sets of outcomes for mentors, mentees, and the program itself. Using logic models can best demonstrate these intricacies because impact will be seen at the individual, programmatic, and institutional levels, requiring program administrators to align and track three distinctly different outcomes.

Theory of Change. As Tayshia develops the logic model, she needs to create a pathway for it to come to life. She does this by creating a theory of change. A successful mentoring program requires holistic planning and strategic thinking. In this regard, it is useful to articulate a theory of change. A theory of change is an explanation of how and why an initiative should work (Weiss, 1995).To do this, Tayshia should consider her outcomes with respect to seven considerations and integrate these factors into the logic model. These elements are (see Table 8.2):

1. Audience. Identifying the population of mentors, mentees, and key stakeholders.

2. Mode. Setting the framework for mentoring.

3. Measurement. Determining the variables you will use to measure effectiveness.

4. Matching. Creating mentor and mentee connections that lead to sustainable and effective relationships.

5. Training. Building capacity in mentors, mentees, and program administrators.

6. Support. Sustaining momentum among mentors and mentees and providing resources.

7. Communication. Providing transparency, broadcasting success, managing expectations.

See Table 8.2 for an explanation of the interrelationship between the logic model and the seven design elements, the significance of each element, and some questions to answer to decide how to apply this framework.

Table 8.2

Seven Design Elements of a Mentoring Initiative

| Element | Logic Model | Purpose | Question(s) to answer | If this is missing or done poorly, then . . . | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Audience | Input | To ensure you are addressing the right population and understand who key stakeholders are. |

What is the population for mentors?

What is the population of mentees?

Who are our other stakeholders?

|

You are not serving the population you intended, don’t garner the support of all who are interested, don’t properly address objections, or identify where you might have resistance. |

What level of experience, tenure, etc., should your mentors have?

At what stage do you provide mentoring to mentees? (pre-admittance, after beginning semester, etc.)

Who else has an interest in mentoring (advisors, dept. heads, admissions dept, etc.)?

|

| Mode | Input |

To ensure that the mentoring initiative achieves desired goal and outcome.

To accommodate imbalances in size of mentor/mentee populations.

|

What framework is most appropriate? |

If you have the wrong mode, you may not achieve the desired outcome.

You may have a mentoring initiative that limits ability to provide mentoring to all who meet the criteria.

|

One-on-one, group, peer, “complementary” (reverse), mentoring triads, mentoring mosaic. |

| Measurement | Output *Note that while this is an output, it should be considered at the beginning of the program. |

Provide quantitative or qualitative indicators of progress or success.

To understand effectiveness.

To choose where and how to adjust the program to meet the desired outcomes.

|

How will we measure success? | You won’t know when/how/whether you have been successful You won’t be able to report outcomes to your stakeholders You won’t be able to course-correct. |

What will we measure?

In your institution, will stakeholders respond better to quantitative data, qualitative data, or anecdotal information?

When, how, and how often will we collect data?

How will we use the data we collect?

How will we ensure responsiveness of the mentors and mentees to our requests for data?

|

| Matching | Activity | Create pairs or groups that are most likely to achieve learning goals and programmatic desired outcomes. | How will we match/pair for optimal learning? |

Attrition of mentoring pairs/groups.

Lack of growth.

Lack of satisfaction or engagement with the program.

Inability or unwillingness of one or more participants in a pair/group to establish trust.

|

To achieve our desired outcome(s), what criteria should we use for matching?

What level of experience will we require as a qualification to become a mentor?

Do we match within or across demographics?

|

| Training | Activity | To ensure mentors and mentees have a shared understanding of expectations of the mentoring process and an opportunity to practice and develop necessary skills. | How do we build capability for effective mentoring? | Mentors and mentees may have misaligned expectations and may not understand the characteristics of effective mentoring. There may be a lack of agency among mentoring pairs for cocreating or repairing relationships. |

For training content:

Do mentors and mentees understand the expectations for participation?

Do mentors and mentees understand the hallmarks of effective mentoring?

Do mentors and mentees understand their respective roles in mentoring success?

Training implementation: Is there a budget for training?

Will training be mandatory?

Will we conduct training in a live, live-virtual, or asynchronous format?

How will we measure if training is successful?

|

| Support | Activity |

To provide resources to mentoring pairs for learning and for mentoring effectiveness.

To ensure continuity and sustained engagement.

To help mentors and mentees navigate unanticipated roadblocks in their relationships.

To create a mentoring community and culture within your organization.

|

How do we ensure momentum, effectiveness, and sustainability? |

Mentoring pairs do not have the tools they need to support their learning.

Mentoring pairs are unable to leverage the best practices and experiences of colleagues in the mentoring cohorts.

Mentor or mentees will abandon relationships that may otherwise have been salvageable.

|

Link to existing leadership development resources.

Coaching capacity within the institution.

How can/will we convene mentors/mentees in a way that they can learn from each other and share best practices.

|

| Communication | Activity |

Recruit mentors and mentees.

To gain support for the program.

To understand the goals and objectives of various stakeholders.

To create champions.

To sustain momentum.

|

How do we communicate with all stakeholders? |

Mentors and mentees may miss key milestones and may not stay on track with learning goals.

Mentoring program will be misaligned with or siloed from other initiatives.

Key stakeholders may lose interest in or lack awareness of achievements within the mentoring program.

|

How often will we communicate about mentoring milestones, achievements, and best practices, and to whom?

What is the preferred method and mode of communication?

How will we seek feedback on the effectiveness of our communication and our mentoring efforts?

Do our mentors and mentees know whom they go to for questions and concerns about the program?

How will we use technology?

How will we gather and share testimonials about the program and mentoring stories to provide motivation and inspiration?

|

Audience. Audience refers both to participants in the mentoring program and to key stakeholders. Creating intentionality around the audience helps ensure that you are including the right population for mentors and mentors. It also helps you identify your key stakeholders so that you can communicate with all interested parties.

Determining the Right Participants. Often, when recruiting participants, program coordinators begin with a broad announcement of an upcoming mentoring initiative with an invitation to apply and select participants from the pool of applicants. While this may garner ample participants, it can also be helpful to intentionally seek out mentors and mentees who will provide feedback and help you generate buzz about your program as it evolves. When you do not take the time to choose the participants carefully, you may end up not serving the population you intended. For Tayshia, whose desired outcome is to increase the graduation rate of first-generation students, the first criteria are obvious—she will want to identify and recruit first-generation students. Similarly, she may want to ensure that she has some mentors in the program with cultural competency and a commitment to that stated outcome. She may also want to seek out some bilingual mentors or mentors in the departments with particularly high numbers of first-generation students.

Questions to consider:

- What level of experience, tenure, etc., should your mentors have?

- Where will find mentees?

- At what stage do you provide mentoring (pre-admittance to develop pipeline), before beginning the program, after the beginning of the semester, etc.)?

Identifying Key Stakeholders. In a mentoring program, the audience is not limited to mentors and mentees. It is important to look at your institution and determine who else has a stake in the success of your initiative; this includes the supervisor, advisor, or dean who directed you to start the program. It also includes anyone else who, by role or interest, could benefit from successfully achieving your desired outcomes. For Tayshia, this includes the Office of Admissions and the Office of Alumni Relations, which could use the success of a mentoring initiative to attract prospective students or donors respectively. You will use this information to guide your communications, determine appropriate objectives and support, and help broadcast successes. If you need assistance with recruiting participants, these key stakeholders could be instrumental.

Questions to consider:

- Who else has an interest in mentoring (advisors, department heads, admissions department, etc.)?

- Who else has an interest in the achievement of our desired outcomes?

- How can we enlist the help and support of these key stakeholders at the beginning and throughout the program?

Mode. There are many different structures for effective mentoring, many of which are discussed in greater detail in Chapter 3. Most institutions default to traditional one-on-one mentoring, in which a more senior person mentors someone more junior. Other modes include:

- Group mentoring: A more senior mentor to more than one mentee in a group setting. This could include mentoring triads or larger groups.

- Peer mentoring: Mutual mentoring or one-way mentoring where there is a common level of experience between mentor and mentee. This could be one-on-one or in a group format.

- Mentoring Mosaic: A diverse group of individuals of different ranks, ages, genders, races, skills, and experiences form a nonhierarchical community (Jackson & Arnold, 2010).

- Complementary Mentoring: Coined by coauthor Lisa Fain and Dr. Lois J. Zachary to refer to what has been known as “reverse” mentoring and renamed to reflect the mutuality of the relationship (see Chapter 3), refers to a structure where a more junior mentor mentors a more senior mentee, usually to provide exposure for the mentor and special knowledge (such as technology, diversity, etc.) for the mentee (Zachary & Fain, 2022).

The mode, too, should be chosen to align with the desired outcome. For example, if Tayshia were to learn that first-generation students perceive a higher degree of psychological safety and community when in groups with other first-generation students, she may want to recommend a group or mosaic model. Likewise, if the goal is to reach as many first-generation students as possible in the first year of the program, but there is a dearth of mentors, a group mode may be preferable. If, however, there is data showing that accountability for outcomes is higher with individual matching, then a traditional or complementary approach may be preferable.

The mode should be selected with intention and purpose and should be consistent with the cultural, psychological, and organizational needs of the participants. If organizations blindly choose the traditional model, or if a mode incompatible with desired outcomes is chosen, results may fall flat.

Questions to consider:

- What mode will best meet the goals of the program?

- What mode will best meet the needs of our participants?

- What mode will best suit the size of our mentoring population?

Tayshia considered a group mentoring model, which she initially thought would make sense because she had a limited pool of qualified mentors and wanted to create community among the students. Ultimately, she chose to implement traditional one-on-one mentoring. She knew the accountability that mentors and mentees would have to one another would help ensure engagement and accountability and thought that this might also serve to boost the connection and involvement of alumni.

Measurement. In the end, an outcome, goal, or objective is only meaningful if you know when you achieve it. Finding qualitative and quantitative indicators of progress or success will help you understand the effectiveness of your efforts and determine where and how to adjust the program to meet desired outcomes. If you do not carefully choose measurements that are linked to outcomes, and you do not periodically check in on progress, you will not know whether you have been successful. You will not be able to course-correct, and you will not be able to report outcomes to your stakeholders.

Consider measurements that address impact at various levels—impact on the mentee and the mentor, effectiveness of program management, impact of mentoring on the department/division, and impact on the institution.

Questions to consider:

- What will we measure?

- In our institution, will stakeholders respond better to quantitative data, qualitative data, or anecdotal information?

- When, how, and how often will we collect data?

- How will we use the data we collect?

- How will we ensure responsiveness of mentors and mentees to our request for data?

As Tayshia looked to decide which measurements would be meaningful, she reviewed her notes from her conversations with key stakeholders. One of the administrators was interested in the overall engagement of the mentors by examining their annual performance reviews before and after being a mentor. Some of the advisors that had a hand in the development of the program wanted to measure academic knowledge by comparing mentored versus nonmentored student performances on final exams. After much consideration, she rejected both of these as measurements because they did not tie closely enough with the overall retention outcome of first-generation students. She knew a fundamentally important measurement would be the graduation rates of first-year students but understood that this would be a lagging indicator that could take several years to measure. She considered measurements at various levels and settled on these factors as measurements in the first 3 years:

- Increased mentee satisfaction with graduate program

- Mentor/mentee satisfaction with program

- Mentee goal achievement

- Willing to recommend/repeat participation in next cohort

Matching. There is both an art and a science to making effective matches. As with each element, matching should be approached with the desired goals and outcomes in mind. Because matching is one of the very first things participants experience about the program, matching effectively is an important way to build trust in and generate commitment to the mentoring program. An ineffective match can forestall trust-building between mentoring partners or undermine participants’ willingness to invest time and energy. As mentoring is a learning relationship, consider how to match mentors and mentees for optimal learning. If matching is done without intention, you risk attrition of mentoring participants, suboptimal results from pairs, and a lack of satisfaction or engagement with the program. There is more on matching in Chapter 9. To match effectively, you need not match for similarity. Indeed, there is beneficial learning, growth, and exposure when matching occurs across differences as well (Fain & Zachary, 2020).

Questions to consider:

- To achieve our desired outcome(s), what criteria should we use for matching?

- What level of experience and what skills will we require as a qualification to become a mentor?

- Do we match within or across demographics?

- What assistance/structure should we set up for mentoring? Will we need a committee to assist?

- If we are implementing a group or peer mentoring model, how do we match across or within groups?

Tayshia decided to create and enlist a committee made up of people from across the business school to help her with matching. She knew she could incorporate different perspectives in the matching and thought it would be an added bonus to help create alignment in various departments if there were other stakeholders who had an investment of time in creating effective pairings.

Training. Too often, mentoring programs fail to achieve their goals because they do not build capability in the mentors and mentees and do not provide adequate resources for their program administrators to prepare participants. To avoid the phenomenon of “pair and pray” (in which mentors and mentees are matched and left on their own to discover what mentoring is and how to do it), it is critical to ensure participants are committed to creating your desired outcomes, have a shared understanding of expectations and an opportunity to practice and develop necessary skills. Training also helps create a sense of agency among all members of a pair or group for cocreating and repairing their relationships. Without training, you will find that mentors and mentees have misaligned expectations about their roles and inaccurate conceptions of effective mentoring. It is nearly impossible to harness the power of mentoring without educating mentors and mentees about the role of a mentor and the best practices of a mentoring relationship.

Questions to consider about training content:

- Do mentors and mentees understand the expectations for participation? Do mentors and mentees understand the hallmarks of effective mentoring?

- Do mentors and mentees understand their respective roles in mentoring success?

Questions to consider about training implementation:

- Is there a budget for training?

- Will training be mandatory?

- Will we conduct training in a live, live virtual, or asynchronous format?

- How will we measure that training is successful?

Tayshia did have a budget for training the mentors and mentees, so she decided to bring in an outside facilitator who could also train her on how to conduct the training for future cohorts. At that training, she wanted to make sure to set the expectation for biweekly check-ins, make sure that mentors understood how their role was different from an advisor, and equip mentees to drive the relationship. She also wanted to share resources that participants may need for achieving their goals and answering their questions. She began to lay out the next steps for making this happen using the template in Figure 8.4.

Support. Providing ongoing support throughout the mentoring period will help ensure continuity and sustained engagement. It will allow your mentoring participants to navigate unanticipated roadblocks and repair their relationship more easily. It will ensure that your participants can access resources that will help them achieve their goals, and it will help create a mentoring community and culture within your institution. Adequate support can help mentoring participants to understand and meet mentoring milestones, ensure they have the resources necessary to further their learning, and assist them in repairing or strengthening their relationships.

Without adequate support, mentoring pairs will not have the tools they need to learn and develop. They will not have a sense of community or the ability to share best practices, and they will not have access to guidance on how to repair or strengthen a relationship that may be faltering. Furthermore, without adequate support, mentors and mentees will be less likely to trust the efficacy of the program, and when the relationship loses momentum, they will be more likely to abandon their relationships.

Support can take many forms, including:

- Providing or linking to resources that will assist with common learning goals

- Creating roundtable discussions among mentors and mentees to create community, share challenges and best practices

- Coaching for mentees and mentors whose relationships stall or fizzle

Questions to consider:

- What resources might assist mentees in common or frequent learning goals?

- Do we have coaching capacity within the institution to assist mentors and mentees? If not, how can we find or develop that capacity?

- How can/will we convene mentors/mentees in a way that they can learn from each other and share best practices?

Tayshia got to work trying to figure out how to provide adequate support on a limited budget. She would create a bank of resources that participants could easily access, which would include answers to frequently asked questions, links to developmental resources, and some information about mentoring best practices. She knew it was important for there to be at least one person that participants could call with questions or concerns, so she asked her supervisor if she could designate herself as that person and receive some training on how to help mentoring pairs get on track. She wanted to build community, too, so she calendared two dates for roundtables—sessions for mentors only or mentees only, where they would meet with each other to discuss the tools and strategies that were working best for them.

Communication. Effective and purposeful communication with stakeholders is also essential to a successful mentoring initiative. It serves to help create awareness, build support, and recruit mentors, mentees, and program champions. Communication is a form of connection. It keeps interested parties aware and engaged, helping you to build trust, better understand stakeholders’ goals and objectives, and integrate these into your own planning when possible. Most significantly, consistent communication will help sustain momentum for your program.

Communication is essential at all stages of the mentoring process—from the announcement of the program to recruitment to training and closure. Mentors and mentees should receive periodic communication offering mentoring tips, sharing resources, and reminding them of mentoring milestones. Gathering testimonials and feedback will help you make program improvements and showcase mentoring achievements. Without effective communication, mentors and mentees may be unaware of key milestones and get derailed from learning goals. If you communicate with others outside of the mentoring program about the initiative, you will avoid misalignment or create distance from other initiatives. Moreover, key stakeholders may lose interest in or lack awareness of achievements within the program, causing an unnecessary loss of program champions and mentoring advocates. It can be helpful to provide a platform for mentoring participants to communicate with you and each other throughout the process.

Questions to consider:

- How often will we communicate about mentoring milestones, achievements, and best practices, and to whom?

- What is the preferred method and mode of communication?

- Will we create a mentoring platform? What technology will we use and how will we make others aware of it?

- How will we seek feedback on the effectiveness of our communication and our mentoring efforts?

- Do our mentors and mentees know whom they go to for questions or concerns about the program?

- How will we gather testimonials and mentoring stories to provide motivation and inspiration?

Tayshia wanted to create a principal place for communication and engagement, so she set up an internal web page with links to resources and information. She also created a regular e-mail cadence to check in on participants, remind them to meet, and sustain engagement by sharing a tip, quote, or resource. She built in two checkpoints during the year where mentors and mentees would share their “wins or testimonials.” When she looked at this plan, she realized that she had not built in communication with other stakeholders, so she set up four dates where she would create a synopsis for other stakeholders that would include the testimonials, a summary of findings from her surveys, and other insights and resources.

Linking Theory of Change Elements and Outcomes

The best advice in mentoring is “the main thing is to keep the main thing the main thing.” It is critical to keep desired outcomes front and center. So, to best use the design element framework above, Tayshia must not lose sight of her outcomes. It is helpful to explicitly link each of these elements to your desired outcomes and goals. Figure 8.4 provides a template in which to do this. By way of example, Table 8.4 shows how Tayshia completed the template.

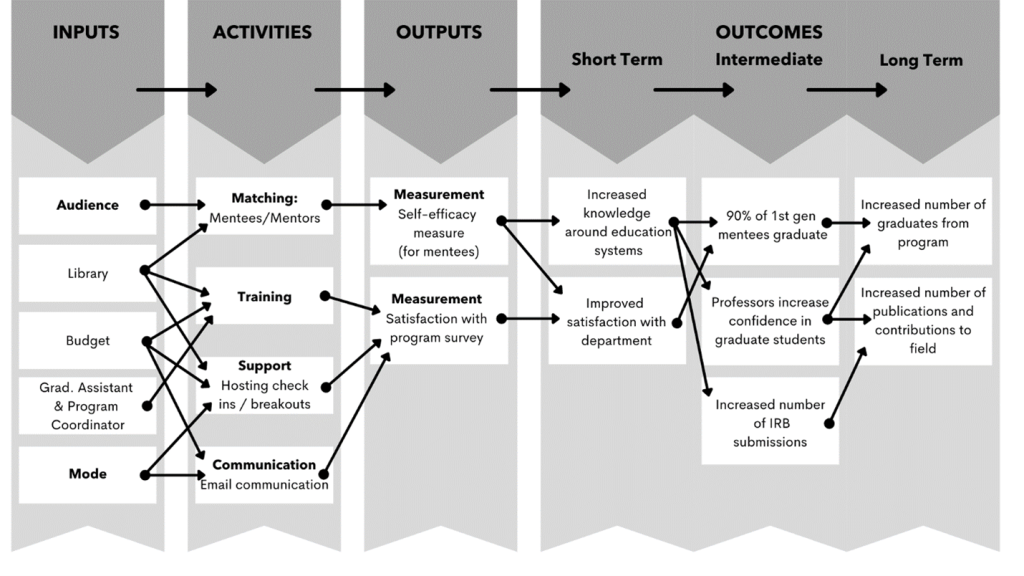

Also, notice that Table 8.2 has a column for the logic model. The seven design elements are integrated in Tayshia’s logic model below (see Figure 8.3). Notice that the design elements fall into the first three steps: the inputs, activities, and outputs. Outcomes are a product of the design elements and activities that you choose to utilize in the mentoring program. Audience and mode are foundational elements that are categorized in the input portion of the logic model. To move forward with activities, coordinators should identify the who (audience) and how (mode). After identifying the audience and mode, the coordinator can move forward with the bulk of the design elements, including matching, training, supporting, and communication plans and implementations.

The last design element to incorporate is located in the outputs portion of the logic model. The measurement should measure specific outcomes. For instance, Tayshia wants to include a self-efficacy measure surrounding navigating educational systems. She chooses this as a way to measure increased confidence regarding education systems. Tayshia could also have chosen other methods of measurement like the number of IRB proposals submitted or student-teacher evaluation scores, but she is specifically interested in learning how the students feel about their knowledge about educational systems. She also includes a program satisfaction measure as a way to evaluate the mentoring program. She can use this information to inform improvements to the program and as an indicator of student retention.

Figure 8.3

Example Logic Model for Tayshia’s Mentoring Initiative

Figure 8.4

Template for Linking Design Elements to Desired Outcomes

| Element | Notes | Link to desired outcome/goal | Task(s) needed |

| Audience | |||

| Mode | |||

| Matching | |||

| Training | |||

| Measurement | |||

| Support | |||

| Communication |

Table 8.4

Linking Design Elements to Desired Outcomes: Tayshia’s Mentoring Program

| Element | Logic model | Notes | Link to desired outcome/goal | Task(s) needed |

| Audience | Input |

Mentees: second-year graduate students

Mentors: alumni, PhD students, and advisors

Admissions office

Academic advisors and faculty

|

Mentees are the target population

Mentors can create accountability and have a vested interest in success

Admissions office can help in recruiting and championing because they can use stats for recruiting

Advisors can help with accountability.

|

Socialize plans with admission and academic advising

Find mentor champions in each group who can help recruit mentors

|

| Mode | Input | Traditional one-on-one mentoring | Helps with engagement and accountability | n/a |

| Matching | Activity |

Create mentoring advisory group to help with matching—have some representation from current/former first-generation students

Create pilot of 18 pairs

|

Will help with alignment | Create advisory group |

| Training | Activity |

Have a kickoff with mentors and mentees at the outset of the program

Set expectations for biweekly check-in

Share resources that participants may need for achieving their goals and answering their questions

Make sure mentors understand their role

Equip mentees to drive the relationship

|

If everyone understands expectations and knows resources available, relationships more likely to stay on track | Determine budget Design training or hire facilitator |

| Measurement | Output |

Increased mentee satisfaction with graduate program

Mentor/mentee satisfaction with program

Mentee goal achievement

Willing to recommend/repeat participation in next cohort

Graduation rates

|

Satisfaction will indicate meeting needs

Goal achievement indicates progress

Repeat participation indicating successful design

Graduation rates—desired high-level outcome

|

Create surveys for beginning, middle, and end of mentoring period

Gather testimonials at end of mentoring period

|

| Support | Activity |

Create a bank of resources and answers to frequently asked questions

Give participants one person to go to for all concerns

Conduct periodic roundtables to build community and share best practices

|

This will build trust in the mentoring program and help sustain momentum

It will link the measurements of “satisfaction with program” and will help create champions

|

Design and schedule roundtables

Identify resources, create list, and post on internal webpage

Designate and train person who is the go-to for participant concerns

|

| Communication | Activity |

Provide internal webpage with links to resources, information

Send e-mails to check-in and remind participants to meet

Share “wins” and testimonials with key stakeholders

Summarize data collected and socialize among key stakeholders

|

This will help build trust and maintain momentum

Hopefully, it will increase engagement and decrease the likelihood of attrition

|

Design, launch, and inform stakeholders of internal webpage

Schedule e-mails

Choose how to collect “wins” and “testimonials”

Create a template for data collection and reporting

|

Conclusion

Tayshia was tasked with developing a strategy to address the lack of knowledge sharing regarding education systems for the graduate students in the business school. She started by conducting a needs assessment, which led her to realize that a mentoring initiative could be valuable for the program. However, she needed to persuade the stakeholders that would be in charge of approval of the initiative proposal. Utilizing empirical research and the goals of the broader program and university, she started by generating lists of outcomes, goals, objectives, and tasks that could be valuable for the mentoring initiative at the business school. After generating these lists, she begins to map out the design elements of the program—audience, mode, matching, training, supporting, and communicating—using a logic model as her guide. In the program logic model, she used boxes and arrows to illustrate the relationships between the inputs, activities, outputs, and outcomes to illustrate the flow from resources to outcomes. By creating a logic model that integrates the outcomes, tasks, and seven design elements, she was able to better inform stakeholders, new staff, administration, and other departments about how she connected resources (inputs) to long-term outcomes (impacts).

References

Allen, T. D. (2003, February). Mentoring others: A dispositional and motivational approach. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 62(1), 134–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(02)00046-5

Allen, T. D., Eby, L., Poteet, M. L., & Lentz, E. (2004). Career benefits associated with mentoring proteges: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.89.1.127

Allen, T. D., Lentz, E., & Day R. (2006, March 1). Career success outcomes associated with mentoring others: A comparison of mentors and non-mentors. Journal of Career Development, 32(3), 272–285. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894845305282942

Allen, T. D., McManus, S. E., & Russell, J. E. A. (1999). Newcomer socialization and stress: Formal peer relationships as a source of support. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 54, 430–470.

Association for Talent Development (ATD). (2012, August 30). Mentoring boosts employee performance. ATD Blog. https://www.td.org/insights/mentoring-boosts-employee-performance

De Janasz, S., & Peiperl, M. (2015, April). CEOs need mentors too. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2015/04/ceos-need-mentors-too

Douglas, E. (2017, February 15). The benefits of onboard coaching: Assuring the success of new executives. Leading Resources Incorporated. Retrieved from: https://leading-resources.com/communication/the-benefits-of-onboard-coaching-assuring-the-success-of-new-executives/

Erickson, E. H. (1962). Childhood and society. Norton.

Fain, L. Z., & Zachary, L. J. (2020). Bridging differences for better mentoring. Barrett-Kohler Publishers.

Gartner Research (2006). Case study: Workforce analytics at Sun. Gartner. https://www.gartner.com/en/documents/497507

Hatry, H. P. (1999). Performance measurements: Getting results. The Urban Institute Press.

Israel, G. D. (2001). Using logic models for program development. University of Florida: Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences. 1–6. https://edis.ifas.ufl/edu/publication/WC041

Jackson, V., & Arnold, R. (2010, November 19). A model of mosaic mentoring. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 13(11), 1371. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2010.9764

Kalev, A., Dobbin, F., & Kelly, E. (2006). Best practices or best guesses? Assessing the efficacy of corporate affirmative action and diversity policies. American Sociological Review, 71, 589–617.

Kekahio, W., Cicchinelli, L., Lawton, B., & Brandon, P. R. (2014). Logic models: A tool for effective program planning, collaboration, and monitoring. (REL 2014-025). Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Education, Institute of Education Sciences, National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Regional Educational Laboratory Pacific. Retrieved from http://ies.ed.gov/ncee/edlabs.

Knowledge at Wharton (producer). (2007, May 16). Workplace loyalties change, but the value of mentoring doesn’t. [Audio podcast]. Knowledge at Wharton. https://knowledge.wharton.upenn.edu/article/workplace-loyalties-change-but-the-value-of-mentoring-doesnt/

Kram, K. E. (1985). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Scott Foresman.

Levinson, D. J., Darrow, D., Klein, E., Levinson, M., & McKee, B. (1978). Seasons of a man’s life. Knopf.

Rush, B., & Ogborne, A. (1996). Program logic models: Expanding their role and structure for program planning and evaluation. The Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 6, 95–106.

Underhill, C. M. (2006, April). The effectiveness of mentoring programs in corporate settings: A meta-analytical review of the literature. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68(2), 292–307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.05.003

Weiss, C. H. (1995). Nothing as practical as good theory. Exploring theory-based evaluation for comprehensive community initiatives for children and families. In J. Connell, A. Kubisch, L. Schorr & C. Weiss (Eds.), New approaches to evaluating comprehensive community initiatives. (pp. 65-92). New York: The Aspen Roundtable Institute.

Weiss, J. W. (2014). Business ethics: A stakeholder and issues management approach (6th ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Wronski, L., & Cohen, J. (2019, July 16). Nine in 10 workers who have a career mentor say they are happy in their jobs. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2019/07/16/nine-in-10-workers-who-have-a-mentor-say-they-are-happy-in-their-jobs.html?msclkid=f7d744b7aae711ec87180209b449eba3

Zachary, L. J., & Fain, L. Z. (2022). The mentor’s guide: Facilitating the effective learning relationships (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass.

[1] It can be beneficial to create a mentoring advisory committee whose members understand and represent the interests of various stakeholders. This will help you socialize and recruit for the program upon launch.