28 Networked Mentoring Programs: Targeted Developmental Relationships and Building a Broader Community

Valerie Paquette; Wendy Murphy; and Susan Duffy

Abstract

We introduce a targeted approach to mentoring programs that considers students’ developmental stage and fosters an inclusive mentoring community. Using the case study of Babson College’s Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership Mentoring Programs, this chapter will detail evidence-based effective practice in delivering high-quality mentoring across distinctive student populations as well as connecting students and mentor volunteers to one another to cultivate a mentoring community. We highlight three mentoring programs: the Undergraduate Near Peer, Undergraduate Professional, and Graduate mentor programs. Each program is designed to match student mentees with developmentally appropriate mentors who provide support tailored to their needs. The Undergraduate Near Peer Mentoring Program pairs first-year students with third or fourth students for adjustment to college and integration with the broader community of diverse leaders. The Undergraduate Professional Mentoring Program pairs junior and senior students with early-career professionals (3–15 years of work experience) for vocational exploration and transition to work opportunities and challenges. The Graduate Mentoring Program pairs graduate students with seasoned professionals (15+ years of executive experience) for more advanced vocational exploration and sophisticated career transition strategies for diverse leaders. Programs are designed to incorporate industry best practices, including participant input for matching, required orientation, mentorship agreements, goal setting, and resources. Across all programs, students and mentors are encouraged to connect with one another through formal program opportunities and to develop a network of relationships to support their journey at Babson College and beyond.

Correspondence and questions about this case study should be sent to the corresponding author – wmurphy@babson.edu

Acknowledgements

We want to recognize the community of students, staff, faculty, and alumni who support the CWEL mentoring programs and contribute to the learning and development that sustains our work. We are grateful for the ongoing support of Babson College, in particular, Donna Levin, CEO of the Arthur M. Blank School for Entrepreneurial Leadership and role model for leaders everywhere.

Mentoring Context and Program Development

The mentoring programs at Babson College’s Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership (CWEL) facilitate meaningful developmental relationships that support students in advancing their personal and professional goals. The program’s focus on women was developed to offset the structural and perceptual barriers for women in networks (Chanland & Murphy, 2018) and align with the mission of the CWEL and the institution.

Babson College is a global leader in entrepreneurship education, with more than 2,600 undergraduate and nearly 1,000 graduate students representing more than 80 countries. The Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership, founded in 2000, was the first center ever focused on women entrepreneurial leaders at a business school. The mission of the CWEL is to close the gender gap in business by advancing gender equity as a growth strategy for individuals, organizations, and society as a whole while educating and empowering students to reach their full potential as inclusive entrepreneurial leaders.

Underpinned by Babson’s leading research on mentoring (Murphy & Kram, 2014) and entrepreneurial leadership development (Greenberg et al., 2011), the CWEL Mentor Program was introduced in the founding year of the center. Originally introduced as a faculty service, the program has evolved and grown over time. Now, with a dedicated team overseeing the program and funding provided through the CWEL student programs operational budget with annual donor support, CWEL offers three dyadic mentorship programs delivered at critical points in our students’ tenure at Babson, serving enrolled undergraduate and graduate students of all gender identities.

Purpose and Objectives of all Programs

The core learning objectives of the programs are to expand and diversify students’ professional networks while applying an individualized approach to develop their own career-readiness skills. Through the practice of professional communication, relationship building, and goal-setting, students are able to increase their professional, academic, and social confidence with perspective and inspiration from relatable, professional role models. They learn to differentiate the roles of mentors, sponsors, coaches, and peer groups and to analyze the structure and context of their current networks and how it impacts their own personal and professional development (Murphy et al., 2017).

Organizational Support for Mentoring Programs and Infrastructure

Program operations and delivery is led by a dedicated program director within the Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership, in coordination with student support staff (both volunteer and part-time work-study employment), staff, faculty, and campus partners. Student employees and volunteers provide valued program support in administrative tasks, student outreach and promotion, the matching process, peer advising, and program evaluation. The CWEL executive director and faculty advisors provide critical expertise and advising to the program staff throughout the design, development, and delivery phases of the program. This includes value-add content development and speaking engagements aimed to enhance both event experiences and resource materials provided to participants. Additional marketing, recruitment, and promotional support is provided by the CWEL team and through valued campus partnerships, including College Advancement and Centers for Career Development.

Operational Definition

At the Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership, we adopted Higgins and Kram’s (2001) definition of mentors as part of students’ developmental network, which is “the set of people a protege identifies as taking an active interest in and action to advance their career.” This set of people includes mentors, coaches, sponsors, and peers, who all play a role in our students’ personal and professional development (Murphy & Kram, 2014). We expect that as a mentor, our volunteers will take a holistic approach, focusing on a broad range of issues, and will offer many types of support, including both psychosocial and career-related, to help the protégé succeed (Dobrow et al., 2012; Kram, 1985). Our mentors are advised to support, encourage, and train students to manage their own learning. They are reminded that their job is not to have all the answers but instead to care, ask good questions, and support the protégé in finding their own solutions.

Theoretical Framework

The CWEL network of mentoring programs is conceptualized based on the literature on positive organizational psychology, specifically that on high-quality connections (Dutton & Heaphy, 2003), and the robust mentoring and developmental network literature (Dobrow et al., 2012; Higgins & Kram, 2001; Kram, 1985), which build on literature in the areas of careers (Sullivan & Baruch, 2009; Hall, 2002) and adult development (Kegan, 1982). These frameworks guided both the structure and content of all aspects of our work, particularly in our expectations of participants and their engagement in each stage of relationship development.

Typology of Programs

Current program offerings include the Undergraduate Near-Peer, Undergraduate Professional, and Graduate mentor programs. Each program is designed to match student mentees with developmentally appropriate mentors who provide support tailored to their needs. The Undergraduate Near-Peer Mentoring Program pairs first-year students with third or fourth year students for adjustment to college and integration with the broader community of diverse leaders. The Undergraduate Professional Mentoring Program pairs junior and senior students with early-career professionals (3–15 years of work experience) in a traditional, hierarchical mentoring relationship for vocational exploration and transition to work opportunities and challenges. The Graduate Mentoring Program is also in the traditional model, pairing graduate students with seasoned professionals (15+ years of executive experience) for more advanced vocational exploration and sophisticated career transition strategies for diverse leaders. Each program runs for 12 weeks and engages 30–60 mentor/protégé pairings within each cohort.

Mentoring Activities

The three programs are each structured in the same format and include key elements that contribute to success according to evidence-based research and practice, including training, networking, support resources, and a compatibility-based matching process (Allen et al., 2009; Ragins, 2012).

Recruitment Activities

Mentors are recruited from the Babson College network of alumni, parents, and friends. They are women who are committed to making a difference in the lives of the next generation of entrepreneurial leaders. They come from a variety of backgrounds and industries, live either locally or abroad, and have their own unique combination of expertise and networks to share.

Individual outreach leveraging staff, faculty, and College Advancement contacts is combined with email, social media campaigns, and word-of-mouth efforts that target alumni, parents, and friends. Direct enrollment periods for mentors begin 4–6 weeks prior to the start of each program; however, recruitment continues throughout the year as a running volunteer interest list built through direct CWEL networking efforts. Salesforce CRM is utilized to track volunteer interest throughout the year as well as manage the enrollment process and historical data. Mentors and protégés are also recorded as pairs in Salesforce to document the relationship.

Student enrollment occurs in the same time period, 4–6 weeks prior to the start of the program. Students are targeted through email, social media, flyers, on-campus tabling, word-of-mouth, peer outreach, and scholarship communities. As a core and consistent offering of the Center for Women’s Entrepreneurial Leadership, the mentorship programs are promoted throughout the year at student orientations and admissions events, allowing students to plan ahead for their participation.

Training Activities

The 12-week program begins with separate 1-hour orientation sessions required for both the mentors and the mentees. In these sessions, participants review goals, expectations, and best practices for the mentoring relationship (Allen et al., 2009; Murrell & Blake-Beard, 2017; Ragins, 2016). The separate sessions for mentors and mentees allow for introductions among the cohort and opportunities to encourage a network of peer support at the start of the program. Students are required to attend prior to committing to the program so they may understand expectations before enrolling.

To enroll, both mentors and mentees complete a questionnaire to share their bio, program goals, LinkedIn profile, life experiences, meeting preferences, and qualities they are looking for in a mentee/mentor. This information is compiled into a participant profile book, which is shared with both students and mentors prior to the kickoff event.

All participants are given access to a Canvas (learning management system) site where various resources, helpful articles, discussions, program guides, and calendars are shared to support them throughout the process. Key guides and materials include but are not limited to an initial conversion guide, a mentorship agreement, goal setting worksheet, and an essential guide to coaching (Murphy & Kram, 2014). In addition to the Canvas platform, participants engage with current and past mentors and mentees via a Babson College CWEL Mentor Network Linkedin group. This group provides an opportunity for participants past and present to connect and share news and resources. This also serves as a channel for stewardship, recruitment, and promotion of additional CWEL and Babson programs.

Matching Activities

The program officially kicks off by bringing all participants together for a reception and speed-networking session. Participants have the opportunity to casually network over a meal and then take part in a structured speed-networking session. Each student has the opportunity to meet each mentor for 3-to-5-minute introductions, then rotates to the next mentor. Note: This program has also been delivered successfully as a virtual session.

At the conclusion of the speed-networking session and after each participant reviews the profile book, both mentors and students submit a matching sheet where they list five preferred matches and opt to share up to five mentors/students that were not a match. Participants are encouraged to look beyond strictly industry alignment and select their preferences based on compatibility. Post-event, CWEL staff reviews the match preference submissions and manually determines the pairings. In the case where a match is not made, staff honor student preferences over the mentor’s or utilize data from the profiles provided to make the best estimate. The pairs are then introduced to each other via email introductions to coordinate their one-to-one mentoring sessions.

Strategies to Monitor and Support Relationships

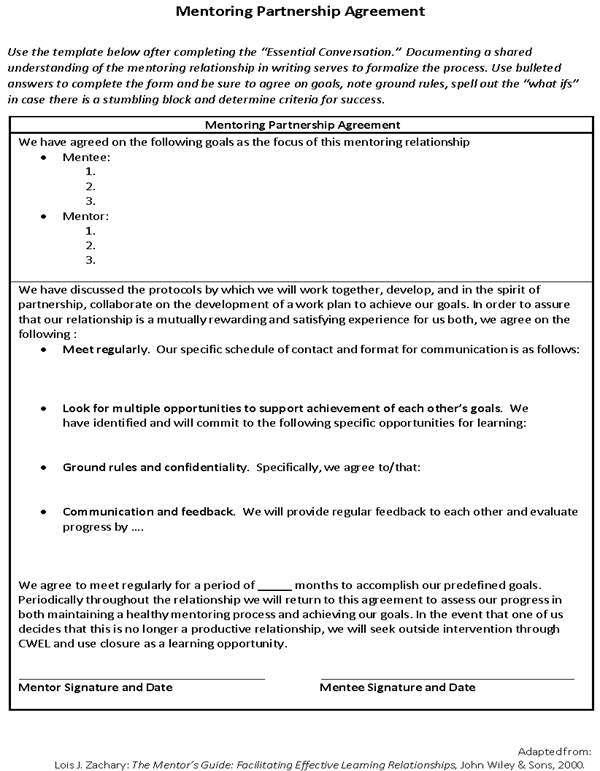

Pairs are advised to schedule at least four virtual or in-person meetings in a cadence of once every other week for the duration of the semester and to determine the schedule and format during their first session. Some pairs opt for variations of that schedule. Students are required to submit their mentorship agreement (see Appendix) and a goal that they set with their mentor for the program after their first session.

As an additional resource for our mentors, we offer the opportunity for the cohort to gather at the mid-point in the program to share ideas and challenges and to network with each other. The open-forum style with a facilitator is offered virtually and provides opportunities for mentors to share advice with each other and offer connections and resources that also further benefit the students. It also serves as a wonderful stewardship and networking opportunity for our dedicated mentor volunteers.

The program director offers open and scheduled office hours throughout the semester to support both students and mentors in their progress and to provide expert advice or counsel as needed. Finally, all programs conclude with a celebratory finale event that brings all participants back together to reflect on the process, celebrate their accomplishments, and demonstrate gratitude toward the program volunteers.

Mentoring Outputs

Since 2018, our programs have facilitated 100+ mentor/mentee pairings annually across our three program offerings, typically serving approximately 50–60 graduate students, 20–30 junior/senior undergraduate students, and 15–30 first-year undergraduate students. Each year, approximately 80 alumni, graduate students, and friends of the college and 15–30 upperclassman undergraduate students volunteer to train and serve as mentors in the program.

Mentoring Outcomes, Sustaining the Program, and Lessons Learned

Outcomes of Programs

Post-finale, all students and mentors complete a survey that evaluates their overall experience. Key success indicators include (a) net promoter score (NPS) of the overall program experience, (b) did the student/mentee reach, progress toward, or pivot from their initial submitted goal to their satisfaction, and (c) will they continue to engage with their mentor/student post-program. The Near-Peer program includes an additional final reflection assignment, where mentoring pairs submit a video or written reflection of their experience, utilizing prompts provided.

Data has been collected by the program director every year and used to make appropriate adjustments to each program. Here, we provide sample results for the Undergraduate Professional Mentoring Program from 2020–2021:

Students

- 90% net promoters overall satisfaction; average score of 9.6 (out of 10)

- 90% plan to continue meeting with their mentor after the close of the program

Mentors

- 73% net promoters overall satisfaction; average score of 8.9 (out of 10)

- 87% plan to continue meeting with their mentee after the close of the program

And sample results for the Graduate Mentoring Program from 2020–2021:

Students

- 58% gave 9/10 overall program satisfaction; average score of 8.7 (out of 10)

- 89% plan to continue meeting with their mentor after the close of the program

- 97% would participate again as a mentee or mentor

Mentors

- 46% gave 9/10 overall program satisfaction; average score of 8.3 (out of 10)

- 77% plan to continue meeting with their mentor after the close of the program

- 82% would participate again, 18% maybe, 0% no

Qualitative data is collected by the program director over time from past participants, both formally for program feedback or marketing purposes and informally through daily interactions with alumni and friends of the college. Comments often include positive themes such as great matches, a well-organized program, enjoying virtual, and positive staff and student energy. Negative comments include issues with students being unresponsive or too busy, challenges of virtual, desire for a longer time frame, and deeper connections with other mentors.

Sustaining the Programs

The CWEL mentoring programs have been successful due to the combination of dedicated staff, institutional support, a cohort-style approach to learning, and the compatibility-based matching process.

Due to the complexity of operations, communications, curriculum development, volunteer management, and stewardship, we recommend assigning a dedicated team to oversee the program. This includes the continuity of the director to build ongoing relationships to ensure sustainability and a dedicated student co-coordinator engaged in the operations, promotion, and program development, which is key to generating excitement, commitment, advising, and accountability among their peers. Providing a high level of service and approachability throughout the experience will generate positive experiences that result in a continuation of repeat mentors and student participants that have experienced the impact and return to give back to others. Proper and transparent transition of leadership should occur to retain key volunteers and student engagement.

In addition to building a dedicated internal team, it is essential to build strong partnerships and trust across the institution. We report on our CWEL mentoring programs as part of our annual report to key institutional partners and alums. Leveraging Advancement and Alumni Relations as key partners will generate new relationships and ongoing positive volunteer engagement while utilizing faculty and staff experts to provide theory and practice behind successful mentoring relationships and best practices to your participants will legitimize the value of the learning experience.

Lessons Learned

To enhance the experience and impact of the program, it is essential to create a cohort environment and engaging opportunities where participants have access and connections to each other beyond their one-to-one pairing through event interactions, online discussion boards, and/or chat groups, profile books, peer meet-ups, and so on. This is especially a value-add for the mentors volunteering their time, who come away with an expanded network of peers in addition to their student mentee.

Salesforce CRM software has been primarily used for mentor recruitment, data management, and relationship tracking. Our program intake forms have been custom-built within Salesforce in order to collect necessary contact information, profile questions, and participation records for our students and mentors. The platform allows us to link our student and mentor accounts to document the relationship, queue a report to facilitate communications, and merge our intake data into a participant profile book that we share with participants at the start of the program. Beyond those functions, we do not utilize Salesforce to facilitate matching, track meetings, or deliver program content. We are currently in the process of vetting other technology platforms that could provide these additional functions and sync with our Salesforce CRM system or custom-building another function within Salesforce.

Finally, we have learned that it is critical to design the matching process to ensure matches based on compatibility ahead of industry or other baseline “on-paper” factors. Empowering participants to meet one another and play an active role in selecting their own matches improves satisfaction with the results and provides an additional opportunity to promote connections across the cohort.

References

Allen, T. D., Finkelstein, L. M., & Poteet, M. L. (2009). Designing workplace mentoring programs: An evidence-based approach. Wiley-Blackwell.

Chanland, D. E., & Murphy, W. M. (2018). Propelling diverse leaders to the top: A developmental network approach. Human Resource Management, 57(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21842.

Dobrow, S. R., Chandler, D. E., Murphy, W. M., & Kram, K. E. (2012). A review of developmental networks: Incorporating a mutuality perspective. Journal of Management, 38(1), 210–242.

Dutton, J. E., & Heaphy, E. D. (2003). The power of high-quality connections. In K. Cameron & J. Dutton (Eds.), Positive organizational scholarship: Foundations of a new discipline (pp. 262–278). Berrett-Koehler Publishers.

Greenberg, D., McKone-Sweet, K., & Wilson, H. J. (2011). The new entrepreneurial leader: Developing leaders who shape social and economic opportunity. Berrett-Kohler.

Hall, D. T. (2002). Careers in and out of organizations. Sage.

Higgins, M. C., & Kram, K. E. (2001). Reconceptualizing mentoring at work: A developmental network perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 264–288.

Kegan, R. (1982). The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Harvard University Press.

Kram, K. E. (1985). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Scott, Foresman & Company.

Murphy, W. M., Gibson, K., & Kram, K. E. (2017). Advancing women through developmental relationships. In S. R. Madsen (Ed.), Handbook of research on gender and leadership. Edward Elgar Publishing.

Murphy, W. M., & Kram, K. E. (2014). Strategic relationships at work: Creating your circle of mentors, sponsors, and peers for success in business and life. McGraw-Hill.

Murrell, A. J., & Blake-Beard, S. (2017). Mentoring diverse leaders: Creating change for people, processes, and paradigms. Routledge.

Ragins, B. R. (2012). Relational mentoring: A positive approach to mentoring at work. In K. Cameron & G. Spreitzer (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of positive organizational scholarship (pp. 519–536). Oxford University Press.

Ragins, B. R. (2016). From the ordinary to the extraordinary: High-quality mentoring relationships at work. Organizational Dynamics, 45, 228–244.

Sullivan, S. E., & Baruch, Y. (2009). Advances in career theory and research: A critical review and agenda for future research. Journal of Management, 35(6), 1542–1571.

Appendix