25 Mentoring Programs for Staff of Educational Institutions: UNM Staff Council Mentorship Program

Amy Hawkins

Abstract

In higher education, staff sometimes feel like the third wheel, the step-child, the forgotten ones sitting on the sidelines as students and faculty bask in the warm glow of academia. Administrators in university settings owe duties to (a) faculty and student needs; and (b) staff development, morale, needs, pay, and benefits. The University of New Mexico’s Staff Council was created so that volunteer university staff elected to serve as councilors can advocate for staff by offering recommendations to the university regarding staff development, morale, needs, pay, and benefits. Each can bring constituent concerns to the full Staff Council and its committees. Staff Council can make recommendations on everything from benefits and parking to award programs. A successful councilor could make the difference between getting a parental leave policy or doing without such a policy, and each bear great responsibility to their constituents and to the university to voice the concerns and will of the staff. The Staff Council Mentoring Program matches councilors with members more experienced to help guide ideas, projects, and initiatives. This chapter outlines the UNM Staff Council department’s structure and details the Staff Council’s focused mentorship program. Then it describes how the program aims to give each team the support it needs to realize its individualized goals. This chapter concludes with a discussion of the implications this program has on outcomes, limitations, and growth prospects.

Correspondence and questions about this chapter should be sent to the author: alhawkins@unm.edu

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the hard-working staff at The University of New Mexico who volunteer their time to advocate for all staff through the work of Staff Council and its committees.

Mentoring Context and Program Development

Purpose and Objectives of the Program

The University of New Mexico Staff Council represents the interests of all staff and serves as an important source of input into the issues and decisions of the university as they relate to the general welfare of the staff of The University of New Mexico (UNM). The Staff Council represents UNM staff to the university administration, and the Staff Council president serves as an advisory member of the Board of Regents.

Councilors represent staff on issues and decisions by making recommendations regarding policy, improving wages, and general conditions of employment (The University of New Mexico, 1996). They participate in the shared governance of the university and advocate for staff through one-on-one meetings with campus administrators, producing resolutions and commentary on campus issues and engaging in opportunities for leadership through participation in committees, monthly business meetings, projects, and events.

In order to be an effective staff councilor, the development of certain skills is crucial. Skills include communicating with constituents and administration, developing programs and events that provide UNM staff support and a forum to address issues of concern, and broadening opportunities for staff to work with people and organizations across the university and our community. The purpose of the UNM Staff Council Mentorship Program is to help councilors develop these skills.

The objectives of the Staff Council Mentorship Program combine the idea of learning skills to be an effective councilor while having the resources to seek out additional opportunities that will help reach an individual goal. It is important that the individual needs of councilors, and what they want to accomplish, are taken into consideration and fostered. The mentorship program, therefore, helps develop skills to be an effective councilor and to gain experience based on councilors’ own ideas of what they wish to accomplish during their time in Staff Council. With the mentorship program, Staff Council is able to guide individuals toward their individual goals with an emphasis on the basics of being an effective representative.

For instance, not long ago, the university had no parental leave policy. One councilor found this to be unacceptable and acted. Working with the Policy Office and Human Resources, this councilor was able to communicate their concerns and learn what was possible through an administrative lens. They translated that information into a resolution (a document introduced by a staff councilor, usually requesting that action on a particular issue be taken), and with the help of a fellow councilor, expert resolution writer, and mentor, the Staff Council adopted the resolution. They then worked very quickly, talking to the administration, connecting the different administrative offices needing to be involved, and through these actions and persistence, the university enacted the policy we have today. There are many skills that this councilor honed during their time in Staff Council that helped gain this outcome. Over 3 years, they excelled as a councilor, committee chair, member of the Executive Committee, finally, Staff Council president, participating in the mentoring program whenever it was offered, first as a mentee and then as a mentor.

Organizational Setting and Population Served

The university is committed to the principle of shared governance and recognizes the right of the council to represent the interests of all staff to the administration. The administration commits resources and support to the council to help ensure its success. The administration has also made a commitment not to interfere with issues and operations of the council and respects the right of the council to adopt positions that they may not agree with. While the council adheres to the requirements of UNM regents’ and administrative policies, the council is independent of the influences of any administrative office.

The Staff Council represents the interests of over 4,000 staff at UNM as a voice in the shared governance of the university. The elected body consists of 60 representatives voted into their seats through a university-wide election to serve a 2-year term representing both job grades and areas. The Staff Council also consists of 12 standing committees, consisting of councilors and noncouncilor staff members, dedicated to carrying out specified charges of the voting council and may also serve the entire staff population, depending on the charge.

Organizational Support for Mentoring Program and Infrastructure

The university provides an annual operating budget, allocates office and conference spaces, and has designated one staff position to provide administrative support to the Staff Council. This position supports all aspects of the council’s initiatives and projects. The Staff Council Mentorship Program was started and is led by volunteers and has limited organizational support. There are no budgetary or human resources allocated specifically for the mentoring program.

Typology of Program

The Staff Council Mentoring Program typically uses one of two typologies: one-to-one hierarchical mentoring or peer mentoring (see Chapter 3 for more details on diverse mentoring forms). There is a broad variety of what councilors may want to learn when they enter the program. Most of our mentoring relationships will be based on the one-to-one hierarchical structure, where the mentor has more experience and a broad scope of practices that the council engages in and will base their mentorship on those skills. This might include how to communicate effectively with constituents, propose an event, or become engaged in one of the committees. Occasionally, however, there is a mentee who may have just as much experience as their mentor in the broad scope of what the council does but wants to learn how to accomplish a very specific task, such as writing a successful resolution like the parental leave resolution mentioned in the previous example. The individuals in this relationship may very well be within the same level and power status within Staff Council; one simply has more knowledge about a specific practice to share.

Mentoring Inputs and Resources

Curriculum Description

Month one: Mentorship program group event #1 facilitated by staff administrator: Expectations and Learning Goals

- Introductions, go over materials distributed via email, and facilitate creating learning plans and goal-making

Month one: First one-on-one meeting for pairs

- Get to know each other and establish reason for participating. Build on a learning plan and goal-making that began at group event #1 by defining learning goal(s) and consider how to meet them over the several months with a timeline.

- Determine frequency and format of meetings. The recommended frequency is at least once a month.

Month two: Mentorship program group event #2 facilitated by staff administrator: (Sample) Topic: Communicating with Constituents

Months two, three, and four:

- As needed, add specific tasks and objectives to the timeline. For instance, if the goal is writing a resolution, a good first step might be to read and review passed resolutions for structure and content.

- Consider if there are networking opportunities that would enable a connection to learn from those already doing what you are interested in. If you are unsure what kind of opportunity may be available, please reach out to the Staff Council administrator, who will do their best to research and set up opportunities that may be helpful in achieving the goal.

- Mentor/mentee check. Is the relationship working? Would a different match opportunity be helpful? No judgment here. Sometimes, through the fault of no one, mentoring relationships do not work out. If a re-match is needed or wanted, please let the Staff Council administrator know.

Month five: Mentorship program group event #3 facilitated by staff administrator: (Sample) Topic: How to Write a Convincing Resolution

Months five, six, and seven:

- Build and finesse the timeline and specific goals. What are the success criteria? How is progress going to be measured?

- Discuss what is being learned so far. Discuss what is working or what is not working. If something is not working, how can the team pivot, reassess, and replan to meet the final goal(s)?

- If working on a project, is the final project something to present or share with others?

Month eight (final month):

- Celebrate! Take stock of lessons learned, directions taken, and what is still needed to be accomplished.

- Present any final projects to Staff Council and/or other groups as appropriate.

- Complete the mentorship program evaluation survey.

There are three optional events for participants of this program. The first is a short introductory event where participants can share expectations of the program and begin talking about learning goals. The remaining two events are determined by the mentorship program interest forms in order to provide content that is most important to that group.

Funding

The university provides a general operating budget to the Staff Council Office and separate funding for university staff appreciation events and university-wide awards. There is no funding dedicated specifically for a mentoring program within Staff Council. There are funding opportunities on a one-time basis that can be requested by any council member, but not a sustained, blanket opportunity to request funding for ongoing mentoring activities.

Mentoring Activities

Recruitment Activities

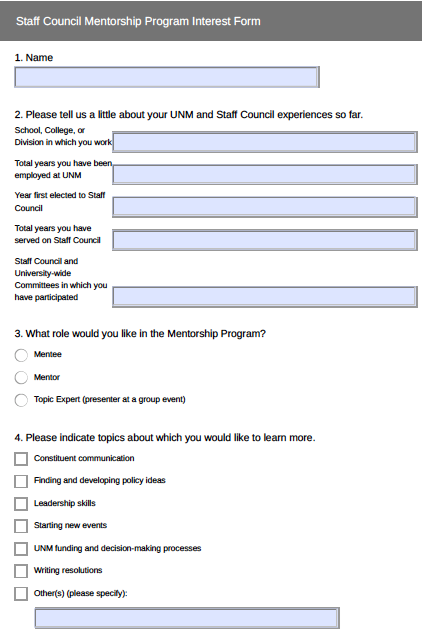

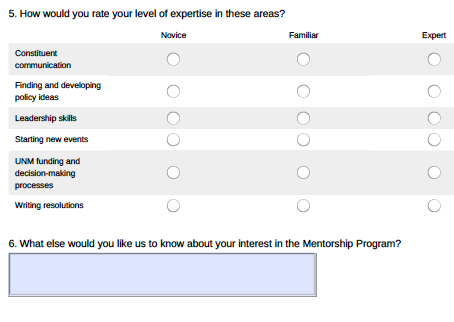

The Staff Council Mentoring Program is very limited in terms of time, lasting only 8 months, with a limited recruitment pool. Mentors, mentees, and topic experts are recruited from the body of councilors, of which there are a maximum of 60 at any one time (UNM Staff Council, 2020). A councilor with a passion for the program will announce the beginning of it during a business meeting that all councilors attend. They will describe the intent of the program and the roles of mentor, mentee, or topic expert and answer any questions that may come up. After this meeting, the Staff Council mentorship interest form (Figure 25.1) is sent to all councilors for those who wish to participate.

Figure 25.1

Staff Council Mentorship Program Interest Form

Matching Activities

There is no guarantee of how many participants there will be since it is a volunteer program, and the councilors self-identify themselves as mentor, mentee, and/or topic expert. After participants sign up for the program and fill out the interest form, pairs are matched primarily by interest (their desired areas of learning and strengths) and secondarily by gender. They are typically matched in one-mentor-to-one-mentee pairs but can occasionally have one mentor to two mentees if there are not enough mentors or if there is a mentor with a particular set of knowledge that is highly sought after. The interest form that all participants fill out includes questions about experiences and expertise, roles within Staff Council, and topics of interest. Once they are paired, participants have the support of one staff administrator and additional resources through their fellow councilors and committee members to call upon for questions, ideas, strategies, funding, networking opportunities, and more, but the impetus remains on them to achieve their outcomes. There are three potential roles defined in the program that councilors can choose for themselves: mentee (any councilor primarily interested in learning and building skills related to Staff Council); mentor (any councilor who has served at least one full term and is primarily interested in sharing what he or she has learned0; and topic expert (any councilor who has served at least one full term with a particular area—or two—of knowledge and experience that they would be interested in sharing in a group setting).

Training Activities

After the pairs are matched, each participant is then sent an initial email that includes their pairings, information for the first gathering of the group, a sample timeline of how to structure their time together, basic guidelines for effective mentoring meetings, and recommendations for how to prep for and what to accomplish during their first one-on-one meeting.

Strategies to Monitor and Support Relationships

During the second month of the program, there is a scheduled mentor/mentee check to determine if the relationship is working. This is an informal check-in at the same time as the second group event and discussion. The participants are encouraged to reach out at any time to the Staff Council administrator if they feel their relationship is not working and would like to be paired with someone else. Other needs and concerns of the mentor/mentee pairs are similarly self-identified to the Staff Council administrator.

Mentoring Outputs: Number of Mentors, Number of Mentees, Mentor/Mentee Ratio

Our current program has seven mentors and eight mentees, giving us six matched pairs with a ratio of 1:1 (1 mentee to 1 mentor) and one matched pair with a 2:1 ratio (2 mentees to 1 mentor). The previous program had six mentors and eight mentees, giving us six matched pairs with a ratio of 1:1 and two matched pairs with a 2:1 ratio.

Mentoring Outcomes and Lessons Learned

Outcomes of Program

Mentoring programs are notoriously hard to keep going without clear structure and consistent oversight. Not surprisingly, the Staff Council Mentorship Program has mixed outcomes. We have had mentees of the program graduate to become Staff Council president, and we have mentees who never met with their mentor and ultimately ended up leaving the organization. Our measure of success for this program is how many participants stick with the program for the full 8 months and continue their work within the council. Currently, our success rate is around 75%. We do tend to see more participation in committees and more involvement in council affairs from those who go through the mentoring program, although this is just an observation. We have no way of tracking the participants’ involvement in the council after completing the program compared to those who do not.

Sustaining the Program

This program is run in a volunteer organization with a severely limited budget and one administrator who tends to the needs of the full Staff Council, its committees, and all the events, programs, and initiative therein. This equates to around 75 individuals, 12 committees, and 25 events ranging in size and complexity per year. The mentoring program is but one initiative out of many, and without another staff dedicated to supporting the initiatives of the program, it is impossible to see that there can be much sustainable growth.

Lessons Learned

We have had some great successes, but the program is severely limited by its short-term, limited recruitment pool and the lack of paid professional oversight and capacity. Another glaring limitation is that outcomes for this program are not clearly defined since every mentor/mentee pair is in charge of their own progress. Ideally, we would also have a solid infrastructure for the mentoring program with training opportunities for our mentors, relationship support for our teams, measurable outcomes, and an evaluation plan to document progress, achievements, and pitfalls of the program. We have learned that sustainability in this format, with this level of support, is difficult to maintain and, to have a more robust mentoring program, we would require dedicated resources and personnel.

Recommendations for Future Designers and Stakeholders of Academic Mentoring Programs

Recommendations for future designers of academic programs include training that includes a component of institutional objectives and curriculum. Training has been shown to have several benefits within a mentoring program for both mentor and mentee (Allan et al., 2006). Although it is not currently within the capacity of the department to run the Staff Council Mentoring Program in as structured a method as we know would be most beneficial, we still consider the successes that we do have significant and worthy of pursuing.

References

Allan, T., Eby, L. T., & Lentz, L. (2006). The relationship between formal mentoring program characteristics and perceived program effectiveness. Personnel Psychology, 59(1), 125–153.

The University of New Mexico. (1996). Regents’ policy manual – section 6.12: University of New Mexico Staff Council. UNM Policy Office – Regents’ Policies. http://policy.unm.edu/regents-policies/section-6/6-12.html

UNM Staff Council. (2020). UNM Staff Council constitution. UNM Staff Council Governing Documents. Retrieved January 22, 2022, from https://staffcouncil.unm.edu/about/pdfs/constitution-2022.pdf