13 Improving Mentoring Relationships and Programs Through Assessment and Evaluation

Laura Gail Lunsford

Abstract

Chapter 13, Improving Mentoring Relationships and Programs Through Assessment and Evaluation, presents frameworks for deciding how to improve mentoring experiences. Assessment activities solicit feedback from or about the participants and focus on participant learning and in situ improvement opportunities. Evaluation efforts determine if the program achieved organizational goals. The chapter has four goals. First, the chapter clarifies the difference between assessment, evaluation, and research. Second, the chapter presents frameworks to guide assessment and evaluation efforts. Third, the chapter describes tools for assessment. Fourth, the chapter describes how to evaluate mentoring programs, what data to collect, when to collect it, and from whom. This section also highlights how to share evaluation data for lay audiences and use it to improve mentoring programs. The chapter concludes with tips for getting started in this important improvement activity.

Correspondence and questions about this chapter should be sent to the author: prof.lunsford@gmail.com

Acknowledgements

Thanks to all the program coordinators who share their challenges with me as they seek to improve mentoring experiences.

Introduction

How do you know what, if anything, should be changed or improved in your mentoring program? This chapter seeks to address this question. Perhaps you inherited an existing mentoring program. If so, how do you know if the previous surveys should be reused? Maybe you have been asked to start a mentoring program. If so, how can you determine if the mentoring program is effective?

I often encounter people who wish to collect information about their program’s effectiveness but are overwhelmed about where to start. Other program coordinators have some data, but they are not sure how to make sense of it. Sometimes program coordinators administer existing surveys, but are then unsure the information helps them to examine the mentoring program’s effectiveness. The focus is usually on getting the program started or underway, and evaluation is viewed as an optional activity to be completed when there is time to do it. But, of course, in many cases that time never arrives.

If people seem happy with their mentoring experience, then why is evaluation needed? Further, informal mentoring is not evaluated, so why should formal mentorship undergo assessment or evaluation? This chapter makes the point that assessment and evaluation are essential activities to ensuring the effectiveness of a mentoring program. There are three reasons to assess and evaluate your mentoring program:

- Steward the resources entrusted to you.

- Achieve desired organizational goals.

- Align with international standards.

First, you need to be a good steward of the resources entrusted to you to coordinate a mentoring program. Resources include money—such as your salary—participants’ time, office space, and a web presence. An ineffective or poorly designed mentoring program wastes these resources.

Second, the mentoring program was established to meet an organizational objective. Formal mentoring programs are supported by organizations to connect people who may not have otherwise found such support. Therefore, it is essential to know if the mentoring program is achieving the organizational goals.

Third, international standards for mentoring programs require assessment and evaluation as markers of an effective mentoring program. The European Mentoring and Coaching Council (n.d.) have “processes for measurement and review” as one of their six standards. The International Mentoring Association (2011) devotes two of its six standards to assessment and evaluation:

- Standard V: Formative evaluation

- Standard VI: Program evaluation

Assessment and evaluation do not have to be complicated. This chapter addresses program evaluation at both the individual level and the program level. You need some information about the participants and their perceptions of the mentoring process and outcomes. You might find that the participants benefit from the program, but you have no idea if the program meets the organizational objectives. For example, first-year freshmen might like their mentors, but you find that the student retention (a goal of your mentoring program) has not increased. Good mentoring programs have data to support claims that they are effective.

In this chapter, you will first learn about the difference between assessment, evaluation, and research. Then, I present theoretical frameworks to provide guidance in making decisions around assessment and evaluation. Formative assessment is described as a way to evaluate the mentoring relationship. Summative assessment is presented as a way to evaluate the program outcomes. I describe who, what, how, and when to evaluate a program, along with examples. The chapter concludes with tips for getting started on this evaluation process.

Assessment, Evaluation, and Research

I have heard my share of sighs when running workshops on how to evaluate mentoring programs. The terms assessment, evaluation, and research can seem confusing or interchangeable. Program coordinators often feel too overwhelmed or overburdened to take on what is perceived as an additional task: finding out if the mentoring program is effective. The job of a mentoring coordinator may be seen as getting the program started or running it. The sense of dread usually stems from the feeling that a research study is needed to find out if a program is effective. You do not need a graduate degree to assess and evaluate your program. The following are the key differences between assessment, evaluation, and research.

Assessment involves direct feedback from mentoring participants about their self-reported experiences. Evaluation involves a judgment from you or others about whether the mentoring program is accomplishing its goals. Research is a testable systematic process and requires a public process to vet the findings, often called peer review. Research is designed to develop or contribute to generalizable knowledge. Chapter 14 goes into more detail about research.

You may have heard the terms formative evaluation and summative evaluation (Lipsey & Cordray, 2000). Formative refers to activities that take place during an intervention (your mentoring program). Such assessment focuses on participant learning in mentoring programs. Formative assessment allows you to make changes during the program to improve program activities. In contrast, summative refers to what happens when the program is over. Summative is the evaluation effort in which you determine if the mentoring program met participant and organizational goals. Thus, formative is to assessment what summative is to evaluation. Both approaches are described in greater detail after the next section on theoretical frameworks for assessment and evaluation.

Theoretical Frameworks for Assessment and Evaluation

Three theoretical frameworks can provide a foundation for your assessment and evaluation efforts:

- Kirkpatrick’s four levels of evaluating training programs

- logic models

- the mentoring ecosystem

The first two frameworks are general evaluation tools, while the mentoring ecosystem highlights specific considerations for mentoring programs.

Kirkpatrick’s Four Levels

Kirkpatrick’s four levels of evaluation originally focused on training programs (Kirkpatrick, 1996). The four levels are reaction, learning, behavior, and results. While mentoring programs are not training programs in a strict sense of the word, they are arguably programs that seek to enhance participants’ skills. Further, this evaluation framework has been applied to other social programs, not just training ones.

Praslova (2010) described how Kirkpatrick’s levels can be adapted to higher education (see Table 13.1). Praslova suggests that the first two levels—reaction and learning—assess what your program does. These levels align with formative assessment. In contrast, the last two levels—behavior and results—will likely occur after your program is over. These two levels align with summative evaluation.

Examples of reaction criteria are participant self-reporting about mentoring activities (e.g., workshops) or the relationship. Learning criteria would be knowledge tests. Such tests might assess if participants learned more about mentorship from an orientation or professional education experience in your program. Learning could also be assessed relative to the goals the participants had when they entered the relationship. Most program evaluation efforts tend to be at the reaction level, in part because it is easier to assess how someone feels about a workshop, another person, or an experience.

Behavior and results refer to summative evaluation. Examples of behavioral criteria are if mentees wrote an effective essay for graduate school or completed an application to graduate school, graduated on time, or completed a project with their mentor. Results are related to the overarching goal of your program and may occur at the organizational level. Examples of results might be if faculty members were retained at the university or if undergraduate mentees were admitted to graduate school. Results align with outcomes in the logic model described next.

Table 13.1

Four-Level Model of Evaluation Criteria Applied to Training in Organizations and Higher Education

| Evaluation criteria | Training in organizations | Learning in higher education | Sample instruments and indicators for higher education |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reaction | trainee affective reactions and utility judgments | student affective reactions and utility judgments | student evaluations of instruction |

| Learning | direct measures of learning outcomes, typically knowledge tests of performance tasks | direct measures of learning outcomes, knowledge tests, performance tasks or other graded work |

national or institutional pre- and post-tests

national standardized field test

examples of class-specific student work

|

| Behavior/transfer | measures of actual on-the-job performance: supervisor ratings or objective indicators of performance/job outputs | evidence of student use of knowledge and skills learned early in the program in subsequent work (e.g., research projects or creative productions, application of learning during internship, development of a professional resume, and other behaviors outside the context in which the initial learning occurred) | end-of-program integration papers of projects, internship diaries, documentation of integrative research work, documentation of community involvement projects, and other materials developed outside the immediate class context |

| Results | productivity gains, increased customer satisfaction, employee morale for management training, profit value gained by organization | alumni career success, graduate school admission, service to society, personal stability | alumni surveys, employer feedback, samples of scholarly or artistic accomplishments, notices of awards, recognition of service, etc. |

Note. Table reprinted from Praslova (2010) with permission from the publisher.

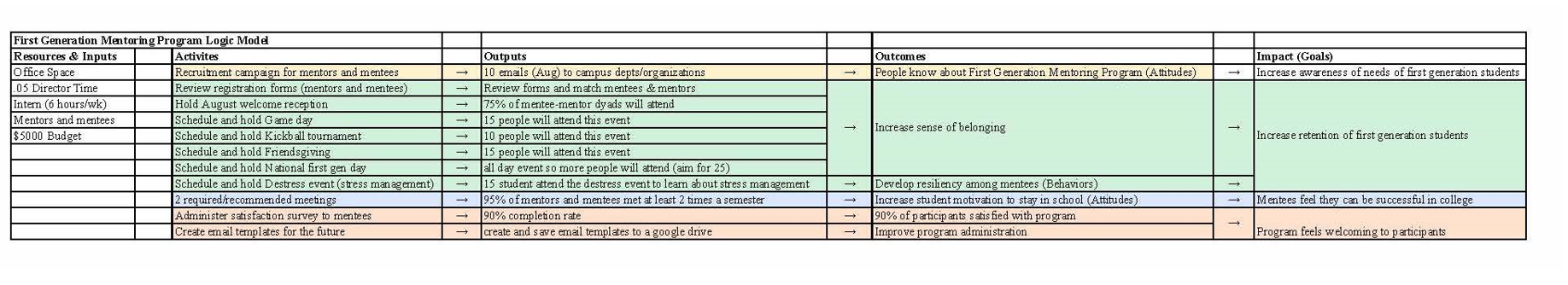

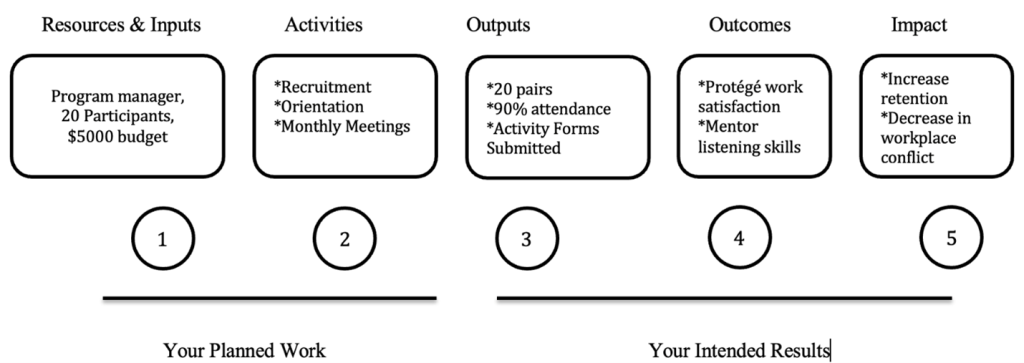

Logic Models

Logic models present a visual representation that connect mentoring program activities to program goals. A logic model is a helpful tool for program evaluation because it makes your theory of change explicit. Your mentoring program seeks to support change for individuals and for your organization, or even for society. The W.K. Kellogg Foundation (2004) has a workbook on logic models that might be helpful if you are unfamiliar with them. See Chapter 8 in this volume for more information about logic models.

Logic models can be drawn in different ways (McLaughlin & Jordan, 1999); however, they present five elements: resources, activities, outputs, outcomes, and impact (see Figure 13.1). You read a logic model from left to right. The planned activities are on the left of the model (Items 1 and 2 in Figure 13.1), while the results of your mentoring program are represented on the right side of the model (Items 3–5 in Figure 13.1). Create a logic model for your mentoring program as you read about each element below. More detail is also provided about mentoring programs and logic models in Lunsford’s (2021) handbook on mentoring programs.

Figure 13.1

Sample Logic Model

Note. Reprinted from Lunsford (2021).

Resources and Inputs

Resources and inputs refer to time, money, facilities, program website, recruitment materials, or similar items needed to operate the program. Your time as the program coordinator, along with the participants’ time, should be considered under resources. Resources can usually be grouped into three categories: program operations, organizational support, and participants. The questions below may help you identify needed resources and inputs.

- Who will benefit most from participating in the mentoring program?

- Which individuals will make the best mentors, and how might these individuals be recruited to participate in the program?

- Will you need office supplies or access to technology through computers and a website?

- How will you document and recognize participation in the mentoring program?

- How much of your time will be devoted to the mentoring program?

- Which organizational leaders need to promote and advocate for the program?

Activities

Activities are expected events or interactions. A program briefing, monthly participant meetings, and a celebration reception at the end of the program are examples of activities. The questions below may help you identify all the program activities.

- What recruitment efforts are needed?

- How will you prepare participants to learn about the program and increase their mentorship skills?

- Is a mentoring agreement expected from the participants?

- What professional development, workshops, or other events will be part of the program?

- How often do you expect participants to meet and what will they discuss or do?

Outputs

Each activity needs to have an output. The outputs provide you with information about the activity. For example, if you have a session on mentoring skills, then identify the related output of that session. One output of such a session might be a knowledge test that participants pass with an 80% score or better. Another output might be attendance or number of participants recruited. A word of caution: Be realistic about outputs; expecting 100% attendance is unreasonable, so make it 90% or 95%. If you do expect 100% attendance, then you need to have make-up opportunities for those individuals who may have an emergency or unavoidable conflict.

Outcomes

Your outcomes are what you expect to happen as a result of activities. Most mentoring programs measure short-term outcomes, such as completing a project in the mentoring program. Your program will have mid-term and long-term outcomes. These outcomes align with the behaviors and results criteria in Kirkpatrick’s model. Examples of mentoring program outcomes might be that mentors learn how to develop rapport more effectively with mentees or that mentees are retained at the institution. Regular mentoring meetings might be expected to result in the outcome of increasing a participant’s sense of belonging or professional identity.

Specifics are important in describing outcomes (Allen & Poteet, 2011). The more specific your outcome, the easier it will be to measure. Revise a general outcome of “increase retention” to “increase retention by 10%.”

Impact

Impact refers to a mentoring program’s overarching goals. How will the participants and organization be changed by the mentoring program? Mentoring programs might have goals such as increasing the number of low-income undergraduates pursuing careers in science.

Summary

A logic model can be shared with stakeholders to make sure you all agree on how the mentoring program activities will achieve the desired changes. A logic model simplifies your decisions about what to assess and evaluate. Consider using a spreadsheet to create a logic model. You may color-code the activities that align with outputs and outcomes (see Appendix for an example). Activities that are not associated with output and outcome need to be removed, as they do not help you achieve your goals, or else an output and outcome needs to be added. Similarly, you might find that you have some outcomes that have no associated activity. The goal is to ensure that all the activities are connected to at least one output and one outcome and that all the outcomes are associated with an activity.

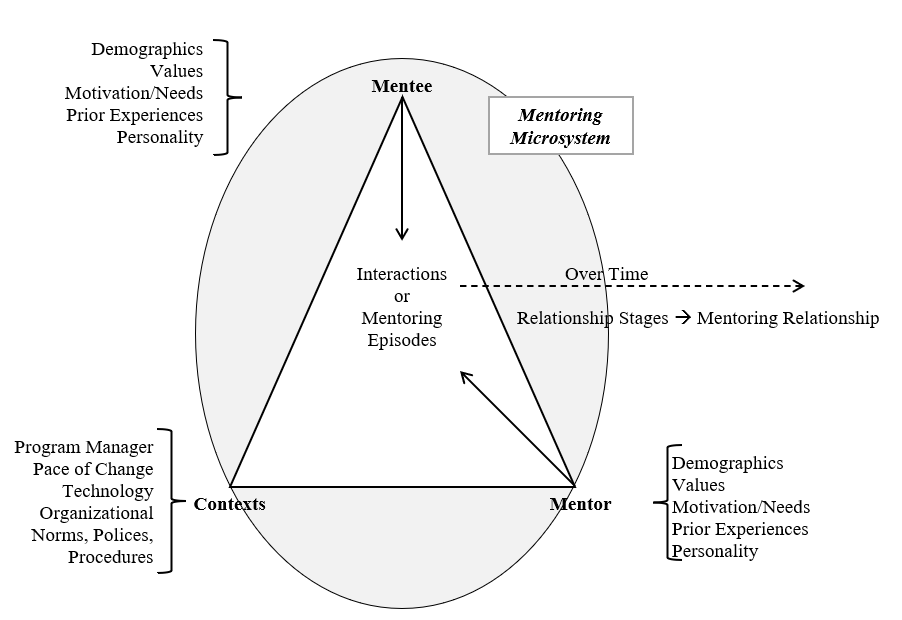

Mentoring Ecosystem

The mentoring ecosystem draws attention to the environment that supports the individuals engaged in mentoring relationships and to the processes by which these relationships unfold (see Figure 13.2). Too often there is a singular focus on the participants. The mentoring ecosystem provides guidance about the process of mentoring and the contextual elements that should be assessed and evaluated.

The mentoring ecosystem is adapted from systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, 1979), which posits that individuals are situated in nested systems. The inner system refers to direct interactions individuals have with others and is called the microsystem.

Microsystems are embedded in settings like departments or colleges. The interaction of a program manager with mentoring participants is part of this larger mesosystem. You may not directly interact with a mentee, but a mentor may come to you for advice about their mentee.

Mesosystems are embedded in exosystems. Other individuals may support or constrain your mentoring program through the resources (budget) they provide or through policies and procedures. The mesosystem influences individuals even though the person is not present in the decision-making.

The mentoring ecosystem also suggests that mentoring relationships develop over time and that different activities may take place in the stages of the mentoring relationship. This model highlights how to think about the policies, procedures, and other indirect effects on your mentoring program that may need to be measured.

Figure 13.2

Mentoring Ecosystem

Formative Assessment: Mentoring Relationships

Formative assessment involves gathering feedback about the effectiveness of mentoring relationships. Such assessment is focused on individual learning. Do the mentees in your program feel the time spent with their mentors is of value? Or do they feel that their mentors are not helpful, which will likely reduce the time they will spend with them. Effective relationships make your program more likely to achieve the desired organizational goals, which you will evaluate as part of your summative assessment. Formative assessment enables you, as a program coordinator, to make improvements while the program is still operating. The main point is to create opportunities that support formative assessment.

Align Assessment with Activities

There are numerous ways to gather feedback for formative assessment. Your assessment efforts, formative or summative, should be aligned with the activities in a logic model that you have developed for your mentoring program.

In brief, logic models visually represent the resources needed for your program, along with the planned activities that comprise your mentoring program. The logic model connects each activity with an output, which lets you know that the activity has been successful. Each activity needs an output, which then guides your formative assessment. Thus, if you hold an orientation and professional development on mentorship skills, then there should be an assessment that indicates if most of the participants attended and, ideally, a knowledge quiz that would evaluate acquisition of the mentorship skills.

The activities are what drive achievement of the desired goals. The model requires you to make explicit your theory of change. In other words, what activities are expected that will achieve the desired outcomes?

Types and Tools

The categories of formative assessment tools for mentoring programs are listed below.

- mentoring contracts

- reflective practices

- coaching mentors

- safety nets

Your program does not need to use all of these tools. You might start with one or two areas for formative assessment and build in more assessment opportunities as your program develops. The selection of tools will depend on what resources you have to support formative assessment and your organizational norms about what would be embraced by participants.

Mentoring Contracts

Many programs ask participants to complete a mentoring contract, sometimes referred to as a mentoring compact or mentoring agreement. The content of these contracts varies, but they usually include:

- expectations about participants, obligations to one another

- logistical information about how often and when to meet

- desired needs and goals

Needs and goals are sometimes presented in a checklist to help participants focus on areas that are relevant to the goals of the mentoring program. The example of the 1st Generation Mentoring Program Agreement shows a checklist for a first-generation mentoring program (see Figure 13.3). Some contracts also include information about communication preferences.

Figure 13.3

Mentoring Program Agreement

Student Name:

Campbell email: Best phone number:

Mentor Name:

Campbell email: Best phone number:

Logistical Information

How often would you like to meet (please circle one):

1 time/week Every other week 2 times/semester

Where will we meet? _________________________

Content Area

In the first column, please rank the order based on what your concerns are in your first year at college. In the second column, please rank the order based on what you think your family’s concerns are. Rank “1” for most interested and “6” for least interested.

| You | Your Family |

| _____ Academic Goal Setting | _____ Academic Goal Setting |

| _____ Financial Management | _____ Financial Management |

| _____ School Life vs. Home Life | _____ School Life vs. Home Life |

| _____ Campus Involvement | _____ Campus Involvement |

| _____ Time Management (study skills, test-taking) | _____ Time Management (study skills, test-taking) |

| _____Social Strategies (interacting with faculty, peers, etc.) | _____Social Strategies (interacting with faculty, peers, etc.) |

Academic Goals

Please list at least two goals you would like to accomplish this year.

Accountability Agreement

Please explain how you would like your mentor to hold you accountable for the goals you listed.

_________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

If you both agree to the information on this form, please sign and date below.

Mentor:

_____________________________

Student:

_____________________________

Elmhurst University has a robust, accredited (by the International Mentoring Association) mentoring program that handles the mentoring contract with several forms. The program requires a separate protégé and mentor agreement with a checklist of the program’s expectations. Participants check off the items and sign and return the form to the program coordinator. In addition, there is a worksheet for “defining your relationship together” that the protégé and mentor complete together at their first meeting. Their forms are located on the Elmhurst University (n.d.) website.

Mentoring compacts are more commonly used with graduate students. The Association of American Medical Colleges (2017) has developed a booklet to present a sample mentoring compact for biomedical graduate students and their research advisors. This compact presents the obligations and expectations that are presumably reviewed in advance of the first student-advisor meeting or perhaps together at that first meeting.

The University of Wisconsin–Madison leads the coordination of several mentorship support centers and activities focused on mentorship in the biomedical workforce. But most of their tools are also applicable to other contexts. Their website presents several examples of mentoring contracts for undergraduates, graduate students, and team mentorship (UW Institute for Clinical and Translational Research, n.d.).

The National Academy of Sciences online portal (https://www.nap.edu/resource/25568/interactive/) on mentorship has additional examples of mentoring compacts and contracts under “Actions and Tools.”

Such contracts support program participants to reflect on their needs and what will make the relationship successful. Signing and submitting the form makes a public commitment that has been shown to increase the likelihood that participants will uphold their obligations to the program and to one another.

These forms need to be collected by program coordinators, who should review them to ensure participants have described plans that align with the program goals. This assessment tool can alert program coordinators to dyads who have not met with one another, which requires intervention and possibly rematching, or to items on the contracts that might present concerns.

Reflective Practices

Reflective practices refer to activities that encourage mentors and mentees to examine their beliefs about mentoring and their mentorship skills. These activities involve self-assessment. Mentoring is about creating learning spaces that support changes in behavior and beliefs. Thus, reflective practices allow participants to increase their self-awareness about their mentoring beliefs and skills. Mentoring philosophy statements, guided questions, and self-assessment are common reflective practices.

A mentoring philosophy statement asks participants to write an essay that reflects their core beliefs and practices about mentoring. Such statements might include their experiences with mentoring, their definition of mentoring, and their beliefs about mentoring others or being mentored. Writing this kind of essay is common in university settings, and there are numerous examples online, such as ones by Davatzes (2016), Dill-McFarland (n.d.), and Ohland (2017).

Guided questions can be used to support mentoring partners through the course of the relationship. Thus, at the start of the relationship, mentoring partners might be asked to share preferences for how to communicate. Is it OK for a mentee to text their mentor, or is email the best communication method between meetings for rescheduling a meeting or addressing an immediate need? Guided question prompts could be provided to participants regularly to guide their discussions during the program. For example, peer mentors in a first-generation mentoring program might be provided questions at the beginning of the program that focus on how to access resources on campus. Questions in the next month might focus on getting involved in campus clubs, while midsemester questions might focus on midterm exams and tutoring opportunities. Mentoring participants can be encouraged to include routine questions at each meeting, such as:

- Share progress on goal(s): behind schedule, on track, ahead of schedule.

- Plus/Delta: what did you like about our meeting today? What can we do differently next time?

Another example of guided questions is to have participants share what they must have in the relationship and what they cannot stand. Some people do not mind if a mentee is late to a meeting, while other mentors might perceive being late as disrespectful behavior. Some programs use an appreciative inquiry strategy; asking people to share a time when they enjoyed collaborating with another person, and then discussing what that experience suggests for the current mentoring relationship. Reflection topics for a first meeting include:

- communication preferences between meetings: text, phone call, email

- must have / cannot stand

- sharing an example of successful collaboration with another person

These activities involve self-assessment that helps individuals consider the relationship they are building together. It is possible to collect information about these activities that can be used for program evaluation. For instance, you might ask participants to share their mentoring philosophies with one another and with the program coordinator. Or you might have a survey early in the relationship to ask if they discussed communication preferences (if you directed them to do that) in their first meeting.

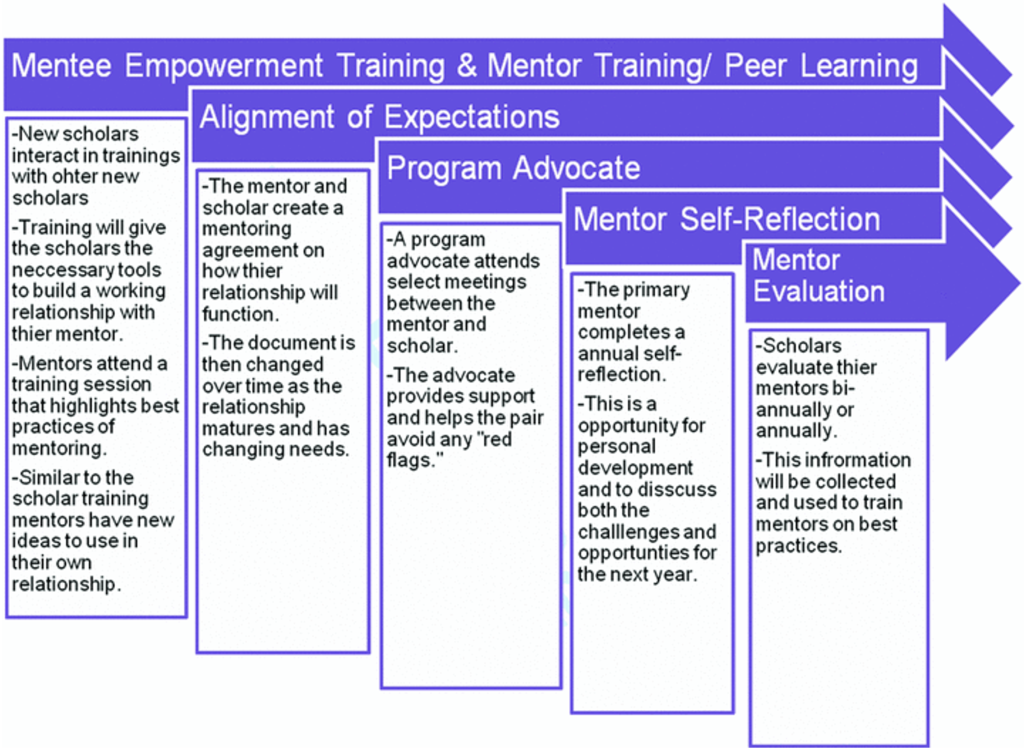

Self-assessment of mentoring competencies is another example of a reflective practice. Some programs ask participants to engage in self-rating at the beginning of the program, while other programs put this task at the end. In both cases, the information can be provided to the program coordinator anonymously to guide future workshops for skill development. Anderson et al. (2011) recommend that evaluation occurs at the end of the program as part of an assessment model that collects information from mentees and mentors (see Figure 13.4).

Figure 13.4

New Model to Evaluate Mentoring Relationship

Note. Figure reprinted from Anderson et al. (2011). Open access.

Consider using existing self-assessment tools that have been validated by scholars. Note that many of the evidence-based examples focus on research. However, they can often be easily adapted to your context (see Table 13.2 for examples). In addition, there are examples of self-reflection assessments on the National Academies portal for the report on The Science of Effective Mentorship in STEMM referenced earlier.

Table 13.2

Self-Assessment Tools

| Measure | Domains | Response Scale | Reference | Audience |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mentor self-reflection template | Communication, expectations research, career support, psychosocial support | Free response | Anderson et al. (2011) | Research mentoring |

| Mentoring Competency Assessment | Communication, expectations, understanding, independence, diversity, and professional development | 26 items 7-item Likert Response |

Fleming et al. (2013)

See full survey here: UW Institute for Clinical and Translational Research b (n.d.)

|

Research mentoring |

| Mentor Strength of Relationship | Affective, logistical | 14 items, Likert scale | Rhodes et al. (2017) | Youth mentoring |

| Youth Strength of Relationship | Positive, negative | 10 items, Likert Scale | Rhodes et al. (2017) | Youth mentoring |

Coaching Mentors

Coaching mentors is another practice that supports formative evaluation. This practice appears to be more commonly used in teaching and health professions. A coach might observe a video of a mentoring session or sit in on a mentoring session. The coach then debriefs the session with the mentor to identify examples of good practices and an area to improve on a skill. There are many resources on coaching others—see, for example, Brilliant Coaching (Starr, 2017) or resources from the New Teacher Center (https://newteachercenter.org/resources/ ). The point of coaching mentors is to provide an opportunity for reflection on their mentoring practices and for further development of their skills.

Communities of practice are another example of coaching mentors. A community of practice provides the opportunity for mentors to share what is effective and areas where help is needed. Perhaps, for example, a mentor is having difficulty helping a mentee overcome an obstacle or develop in a desired area. Suggestions from other mentors who have faced similar situations can be helpful. Scholars find that communities of practice for mentors can build access to resources, increase motivation to be an effective mentor, and enhance one’s identity as a mentor (Holland, 2018).

Safety Nets

Formative assessment can be used to reduce negative mentoring experiences. Unfortunately, mentoring is not an effective relationship for everyone. Although dysfunctional relationships are not common, they do occur. It is critical that formal mentoring programs have a process to identify problems early to facilitate a graceful exit or what some call a no-fault divorce.

Establishing an early check-in at the start of the mentoring program is one example of a safety net. You might have a survey or request that mentoring partners submit a report about their first mentoring meeting. If pairs have not met yet, the program manager can intervene to discern the problem and rematch the individuals as needed. It might be that their schedules do not match, or a personal crisis might make it impossible for a person to participate in mentoring after all. Some programs provide the option to indicate in a survey if a mentor or mentee wishes to be rematched.

The point is to provide an opportunity for participants to indicate they can no longer participate or that they wish to be rematched. Programs that lack such opportunities may leave participants feeling that they have failed someone in the relationship. Mentoring programs are meant to motivate and empower participants, not leave them feeling like a failure.

Formative Assessment Can Contribute to Evaluation.

You might be wondering, “Can I use formative assessment for program evaluation purposes?” The answer is yes. Assessment can provide information during the program that improves participants’ experiences, and it may provide you with information at the end of the program about whether the program achieved its goals.

To use formative assessment for evaluation purposes, it is useful to collect baseline data on the areas of interest to track changes over the course of the mentoring program. Baseline data refers to data on participants or the organization that is collected before the mentoring program starts. Use your logic model to collect relevant information related to the program goals so that you will be able to assess if there is a change in these indicators.

Baseline and subsequent data need to have identifying information to track the change for a person over time. If a goal of the mentoring program is to increase mentee career identity, you might collect that information in an application at the start of the program and at the end of the program in a survey. The information in the application might be shared with the mentor as part of a formative assessment. Changes at the end of the mentoring program can then provide information to evaluate the success of the program.

You could collect data from anonymous surveys to guide future mentoring workshops during the program and examine it at the end of the program to determine if the workshops met the intended program goals. Asking participants to complete session feedback reports is another way of collecting information that provides the participants time for reflection and provides you program-level feedback on meeting frequency and success.

This section was about formative evaluation, but you can also use this data as part of your summative evaluation of the program, which is described in the next section.

Participant Consent

Obtaining participant consent is a topic you need to consider at the start of your assessment efforts. Participant consent relates to research ethics; and remember that assessment and evaluation are not research studies. Universities have different practices related to their institutional research activities. This chapter discusses assessment that is related to determining the effectiveness of educational interventions. Such practices are not research activities and would be categorized as exempt from research. However, some institutions want any projects that are exempt from research to receive that designation from the institutional review board (IRB) or other ethical oversight committees. For more information about the IRB, see Chapter 14.

Assuming that your IRB agrees that your evaluation effort is exempt from review, you do not need participant consent to collect evaluation data. However, you should be prudent and careful in collecting identifying information as part of good practice. I suggest these practices:

- Anonymize data when possible.

- Refer to identified data by numbers, rather than by name, in any reports.

- Report data in the aggregate so that individuals cannot be identified; if the categories are too small, then combine them. For example, if there are only two women in one major, you should not report gender by major or combine the major with another one.

If you do plan to present your evaluation results, your work may be considered research (see Chapter 14), and participant consent may need to be obtained to include their data in your presentation.

Summative Evaluation: Mentoring Program

Evaluation occurs when the program is over. It is a summative practice that lets you know if the mentoring program achieved the desired goals and reflects your efforts to make that evaluation. It is important to evaluate your program to ensure that the program goals are achieved. If they are not achieved, then evaluation can help you determine what needs to be changed to improve the program next time to achieve the desired goals.

Evaluation is your way of determining if the program met the needs of the individuals and the organization. Your logic model should guide your evaluation efforts. In other words, there is no need to collect information that is not related to the outcomes in your logic model. Conversely, it is important to have data and information about each of the outcomes listed in your logic model. Evaluation activities provide you with data on the outcomes of your mentoring program.

This section first presents methods and designs used to evaluate mentoring programs, then highlights information about when, how, and from whom to collect data. I then present suggestions for summarizing data for a lay audience.

Methods

Method refers to your approach to collecting information. Quantitative information is numerical and can be analyzed statistically if you have a large enough sample. Qualitative information is not easily summarized numerically. It might refer to written responses, photographs, or observations. Qualitative data can be transformed into numerical data by categorizing information.

There are benefits and costs to collecting both types of data. Quantitative data is easier to summarize using means or frequencies; for example, how many mentees applied to graduate school. However, it may not present the holistic experience of your mentoring program; for example, the challenges a mentee overcame with their mentor to apply to graduate school. On the other hand, qualitative data can provide vital details about the mentoring experiences. However, it can be time-consuming to summarize and share qualitative data with others.

An effective practice is to collect a combination of quantitative and qualitative data. For example, you might have a survey with Likert responses (1–5) with one free-response question. You might also keep attendance and meeting records along with a few photographs and quotes about key mentoring activities.

Design

An evaluation of the program’s effectiveness requires some type of comparison, either with the participants before they started the program or with similar people who did not participate in the mentoring program. If all you have is a survey at the end of the program for only the program participants, then you have not engaged in evaluation. It is possible that people would have changed over time anyway, and it had nothing to do with the mentoring program.

There are two main designs for an evaluation effort: (a) control group comparison, and (b) time series.

Control Group Comparisons

Using a control group allows you to compare the outcomes your mentoring participants report to a similar group who did not participate in mentoring. Some programs use a waitlist control group, made possible when more people wish to participate than you can accommodate in the mentoring program. You can randomly assign some people to the program and the rest to a waitlist. You can then administer a similar survey to both groups to assess differences in outcomes between participants and non-participants. Presumably, you will select the people from the waitlist to participate in the next round of your program.

Another way to create a control group is to identify people similar to your participants, perhaps by grade point average or when they started at your institution. Mentoring programs for first-generation students often work with their institutional research office to find a similar sample of students by grade point average and year in school to determine if students in the mentoring program have increased retention.

Time Series

A time-series comparison means you are examining changes over time for participants. Thus, you would collect relevant information related to the program outcomes at the start of the program (referred to as baseline or Time 0 data) and then at key points in the program (Time 1 or Time 2). For example, if a goal of the mentoring program is to increase faculty members’ scholarly productivity, a short survey may have a question at Time 0 about how many articles they published or submitted in the last 12 months, and then a similar question is posed at 6-month intervals. The hope might be that for people in the mentoring program the number of articles published later in the program is greater than the number of articles published at Time 0 .

When to Collect Data

Unless your program is shorter than 2 or 3 months, consider having three or four data collection points: at the beginning of the program, a month into the program (to make sure people are meeting), in the middle of the program, and at the end of the program. Of course, you do not need to collect the same data at every interval, but collecting similar information at the beginning and end could provide information about if the program resulted in the desired changes.

It is also helpful to examine data from program activities. If the program was not successful, then examining which activities might have had low attendance or did not go as planned might provide information about program changes. Similarly, if the program goals were met but few people participated in certain program activities, those activities might not be needed.

The timing of data collection efforts needs to align with your organizational calendar to avoid times that would lead to low response rates. For example, students will be unlikely to complete a survey during an exam week, and faculty members are unlikely to complete a survey over a summer break.

Your logic model should be a guide for when to collect information. Surveying participants monthly can become burdensome. However, having an evaluation at the end of a workshop will likely get you the needed information about that activity. Too little information means you do not have enough data to determine the effectiveness of program activities and outcomes. It is helpful to design a calendar at the start of the mentoring program that will highlight what data to collect and when. This information can also be shared with participants so they can be encouraged to fill out a survey before the survey arrives.

How to Collect Data

Most program managers rely on surveys to collect information. However, focus groups, interviews, and archival evidence are also useful data points. In the following sections, I briefly review each approach.

Surveys

Surveys are frequently used in evaluation efforts, and rightly so. With online survey software, they can be easy to automate, administer, and summarize. There are best practices for writing surveys and survey questions, which are beyond the scope of this chapter. However, there are three suggestions that might help you use surveys effectively.

First, use or adapt evidence-based surveys that have been used and tested by others. Resources in the assessment section above provide numerous examples. If you must create your own survey, then be sure to test it on others before sending it out to everyone.

Second, keep the survey as short as possible and have only one or two free-response questions. Short surveys will increase your response rate.

Third, be sure to share the results of the surveys with participants so they may be encouraged that you are using their information. This feedback may make them more likely to view completing surveys about the program as worthwhile.

Focus Groups

Use a focus group when you do not know enough to ask a succinct survey question. Perhaps there is a new component to the program, or you wish to examine a particular aspect of the mentoring program in depth. Focus groups should involve five to seven people and last 20 to 45 minutes. A focus group allows you to collect more detailed, nuanced information in a more efficient manner than in an interview.

There is a skill to conducting focus groups so that you do not unintentionally lead the participants to respond in certain ways to please you. Thus, be sure to practice, and prepare your questions to be open-ended and objective. Avoid questions that can be answered with a yes or no response. Rather than asking, “Did you like the mentoring program?” you might ask, “Describe what activity was most meaningful to you in the mentoring program.”

Interviews

In general, I discourage the use of interviews, as they are time intensive to conduct and to summarize. However, there are times when interviews might provide evaluation information, especially if there is also a research component to the program. There are two other times when interviews might be warranted. First, if you have survey data that points to a problem, then you might want to conduct a few interviews to get more insight into changes that need to be made. You may have a survey response about a negative mentoring experience that escaped your safety net. It would be meaningful to talk to that person to learn more about what happened, how to prevent it in the future, and how to rematch or support the person.

Second, you may wish to interview participants who report exceptional experiences. An interview might provide insight into mentoring practices that could be shared with future participants.

Archival Data

Finally, remember to include archival data in your evaluation. Such data might include photographs of events that document attendance or key program activities. Unsolicited emails and assessment information is also archival data that can provide insight into the program’s effectiveness.

From Whom to Collect Data (Participants and Stakeholders)

Most program coordinators collect information from mentees. However, be sure to collect data from mentors and other stakeholders. Such data will give you multiple perspectives to assess the effectiveness of the mentoring program.

Evaluation Summaries

It is important to prepare a brief report of your evaluation data to share with your stakeholders. Consider adopting the practice of creating an annual report or success story about your mentoring program. Rather than having pages of charts, tables, and reports, try to organize your data according to your mentoring program’s key activities and goals.

Many program coordinators find a simple template helpful. Create a success story that has one or two tables or charts of data that provide information about your program goals, a couple of quotes from program participants, and a couple of photographs that highlight key program activities. This summary requires you to select the key data points, and it enables you to get feedback from stakeholders about the program’s effectiveness.

There may be evaluation results that suggest changes are needed. Establishing an annual practice to examine the data with others, perhaps an advisory board, can help you to use evaluation information to improve the mentoring program.

Tips for Getting Started

In this chapter, I try to point out that assessment and evaluation are important activities that do not have to be complicated. Take these actions to get started. Administer a short survey at the beginning and end of the program that asks participants questions related to the program goals. Have a one-item check-in question after the first month of the program to ensure people are meeting. This check-in will enable you to rematch pairs or intervene so that participants are actually participating in your program. Provide a short evaluation of required events; see Lunsford’s (2021) The Mentor’s Guide for a suggested evaluation. Create one or two opportunities for participants to self-assess their progress in the mentoring program. Then, summarize this data annually and review it with stakeholders.

You do not need to have a comprehensive assessment and evaluation effort in your first year. Engaging in small, iterative improvements will be less overwhelming for you and your participants. Establishing a practice of assessment and evaluation, however, will create a culture that will support your participants and let you know if the mentoring program is successful.

Conclusion

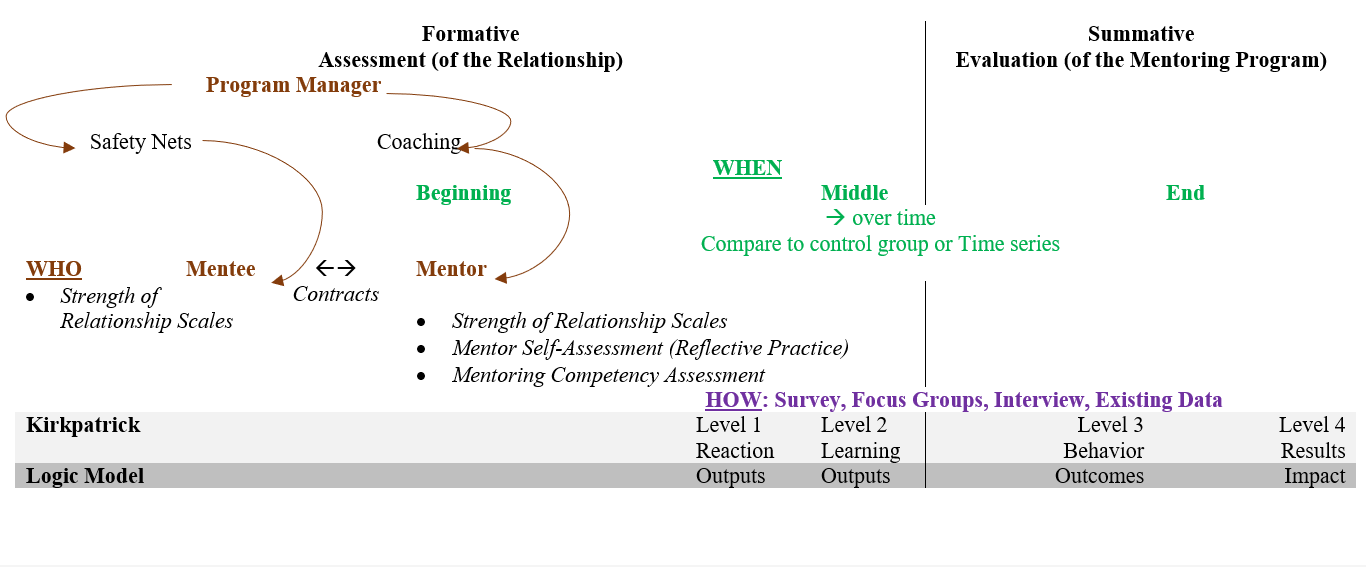

Figure 13.5 presents an overview of the formative and summative activities described in this chapter. The formative activities refer to assessing the relationship. The program coordinator is directly involved in these activities by checking in to make sure participants are thriving in the mentoring relationship and resolving any problems (safety net and coaching). At the beginning of the relationship, mentees and mentors may complete a mentoring contract or take other assessments, listed in the table, to provide an opportunity to reflect on their mentoring skills and relationship. Levels 1 and 2 in the Kirkpatrick model, and measuring outputs in a logic model, are the key formative assessment activities.

Summative assessment includes comparing mentoring participants to non-participants (a control group) or collecting information on change over time. Summative assessment focuses on Levels 3 and 4 in the Kirkpatrick model and on measuring outcomes and impact in a logic model.

The information in this chapter will help you to be confident in making claims about the effectiveness of your mentoring program. Mentoring programs are resource-intensive and it is important to use those resources wisely and well. Learn to create assessment opportunities in your mentoring program for your participants to reflect on their progress in ways that alert you to potential problems (and to successes). Evaluation, which occurs after the program is completed, will help you determine if the mentoring program achieved its goals.

Figure 13.5

Chapter Overview of Formative and Summative Activities

References

Allen, T. D., & Poteet, M. L. (2011, March). Enhancing our knowledge of mentoring with a person-centric approach. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 4(1), 126–130. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1754-9434.2010.01310.x

Anderson, L., Silet, K., & Fleming, M. (2012, November 28). Evaluating and giving feedback to mentors: New evidence‐based approaches. Clinical and Translational Science, 5(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-8062.2011.00361.x

Association of American Medical Colleges. (2017, January). Compact between biomedical graduate students and their research advisors: A framework for aligning the graduate student mentor-mentee relationship. AAMC. https://store.aamc.org/downloadable/download/sample/sample_id/99/

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development: Experiments by nature and design. Harvard University press.

Davatzes, N. C. (2016). Mentoring philosophy: Creating choice, building skill, instilling confidence and integrity. Temple University Earth and Environmental Science. https://sites.temple.edu/ncdavatzes/sample-page/mentoring-philosophy/

Dill-McFarland, K. (n.d.). Mentoring philosophy. Kimberly Dill-McFarland Teaching Portfolio. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://sites.google.com/a/wisc.edu/kimberly-dillmcfarland-teaching-portfolio/philosophy/mentoring-philosophy

Elmhurst University. (n.d.). Mentoring and shadowing. Elmhurst University. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://www.elmhurst.edu/academics/career-education/mentoring-and-shadowing/

European Mentoring and Coaching Council. (n.d.). ISMCP standards: The self-assessment framework for ISMCP accreditation. EMCC Global. Retrieved October 8, 2022, from https://www.emccglobal.org/accreditation/ismcp/standards/

Fleming, M., House, M. S., Shewakramani, M. V., Yu, L., Garbutt, J., McGee, R., Kroenke, K., Abedin, Z., & Rubio, D. M. (2013, July). The mentoring competency assessment: Validation of a new instrument to evaluate skills of research mentors. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 88(7), 1002. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e318295e298

Holland, E. (2018, May 18). Mentoring communities of practice: What’s in it for the mentor? International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 7(2), 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-04-2017-0034

International Mentoring Association. (2011, June 13). Mentoring program standards (Document No. 1). International Mentoring Association. https://www.mentoringassociation.org/assets/docs/IMA-Program-Standards-Rev-6-04-2011.pdf

Kirkpatrick, D. L. (1996). Invited reaction: reaction to Holton article. Human Resource Development Quarterly, 7, 23–25.

Lipsey, M. W., & Cordray, D. S. (2000). Evaluation methods for social intervention. Annual Review of Psychology, 51(1), 345–375.

Lunsford, L. (2021). The mentor’s guide: Five steps to build a successful mentor program. Routledge.

McLaughlin, J. A., & Jordan, G. B. (1999). Logic models: A tool for telling your programs performance story. Evaluation and Program Planning, 22(1), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-7189(98)00042-1

Ohland, M. W. (2017, September 29). Mentoring philosophy statement. Purdue University. https://engineering.purdue.edu/ENE/Images/Ohland_Mentoring_Philosophy_Statement.pdf

Praslova, L. (2010, May 25). Adaptation of Kirkpatrick’s four level model of training criteria to assessment of learning outcomes and program evaluation in higher education. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 22(3), 215–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-010-9098-7

Rhodes, J. E., Schwartz, S. E., Willis, M. M., & Wu, M. B. (2017). Validating a mentoring relationship quality scale: Does match strength predict match length? Youth & Society, 49(4), 415–437. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X14531604

Starr, J. (2017). Brilliant Coaching 3e: How to be a brilliant coach in your workplace. Pearson UK.

UW Institute for Clinical and Translational Research. (n.d.). Mentoring compacts/contracts examples. University of Wisconsin-Madison ICTR. Retrieved April 25, 2022, from https://ictr.wisc.edu/mentoring/mentoring-compactscontracts-examples/

W.K. Kellogg Foundation. (2004, January 1). Logic model development guide. W.K. Kellogg Foundation. https://wkkf.issuelab.org/resource/logic-model-development-guide.html

Appendix