12 A New Vision for Promoting Equity and Inclusion in Academic Mentoring Programs

Assata Zerai and Nancy López

Abstract

What are the pitfalls of conventional student, faculty, and staff mentoring programs? Despite good intentions, how might they negatively impact Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC), as well as other marginalized faculty who are women, LGBTQIA+, Persons with Disabilities (PWD), or first-generation college students (e.g., grew up in household where no parent/legal guardian earned a four-year college degree in the United States or abroad)? How could employing an intersectional framework—attention to the simultaneity of systems of oppression and resistance—as inquiry and praxis transform student, faculty, and staff mentoring programs? This chapter examines the challenges and possibilities for advancing equity and inclusion that considers simultaneous and complex social identities and statuses of faculty, students and staff (and complex identities such as BIPOC, women, first-generation college status, and/or PWD), as relevant to structuring successful mentoring programs.

In this chapter, we (a) explain the vital necessity of mentoring to advance inclusive excellence, (b) discuss mentors’ role in designing strategies for creating more inclusive educational and scholarly environments, and (c) review impediments to successful mentoring practices that have deleterious effects on students, faculty, and staff who are BIPOC, women, PWD, LGBTQIA+, and first-generation college status. This review shines a light on a number of common missteps in mentoring relationships, including senior staff and faculty members’ fixed mindsets and one-dimensional approaches toward students, staff, and junior faculty from marginalized groups; deficit perspectives about junior faculty members’ intellectual contributions; color-, gender-, disability-, class-, and other power-evasive perspectives on the part of senior faculty and their resultant lack of intervention when students, staff, and junior faculty are targets of microaggressions and bullying; insensitive and triggering comments by senior faculty (even as content in conventional mentoring trainings); and lack of critical reflexivity amongst faculty who have been assigned to serve as mentors to BIPOC, PWD, LGBTQIA+, first-generation college status, students, staff, and other faculty.

Based on this review, we recommend several promising practices for mentoring BIPOC, PWD, LGBTQIA+, first-generation college status, and other minoritized students, staff, and faculty at all ranks, including but not limited to the importance of critical reflexivity and centering the assets of mentees so that senior faculty can become better mentors to students (both undergraduate and graduate), staff, and other faculty.

Correspondence and questions about this chapter should be sent to the first author – zerai@unm.edu

Introduction

As colleges and universities in the United States become increasingly diverse, it is critically important to develop faculty from backgrounds traditionally underrepresented in higher education. Many faculty of privileged race, gender, and class status desire to learn more about mentoring early-career faculty, staff, and students who are from underrepresented and marginalized backgrounds. This chapter examines the pitfalls of traditional faculty, staff, and student mentoring approaches that have cumulative and consequential deleterious effects on Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC, to include Asian/Asian American and Pacific Islander [AAPI], Latinx, and multiracial individuals) and underrepresented racial minorities (URM—Black, Indigenous, and Latinx) faculty in particular, as well as for women, LGBTQIA+ folks, persons with disabilities (PWD), or those who were in the first generation of their families to complete baccalaureate degrees.

What is your mentoring story? Think back to when you were an undergraduate or graduate student. Professor Kimberlè Crenshaw, the African American legal scholar who coined the term intersectionality, shared a story about mentoring as a part of her presentation at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association in 2016 that resonated with us. When she was a first-year student in law school, she went to talk to one of her professors, a white man, during office hours, and he immediately assumed that she was struggling in class. Rather than ignore his comments, she replied: “I know Bobby and Suzy, white law students, come to your office frequently; have you ever asked them if they are struggling in class?”

Professor Nancy López, a Black Latina, US-born daughter of Dominican immigrant parents who never had the opportunity to pursue formal schooling beyond the second grade and were rich in cultural wealth, remembers meeting one of her graduate instructors to talk about her research interest in race and education with the goal of producing policy-relevant research on Black Latinx communities; her advisor, a white man, responded with disdain, “You came to graduate school so you can help your community?” Indeed, throughout her career, Dr. López received messages that research, teaching, and community engagement about race, intersectionality, and social justice were problematic (López, 2019; Muhammad & López, 2023).

We tell these stories to call attention to the vital necessity of effective mentoring for the future of academia. We ask: How could the lack of critical reflexivity about power, difference, implicit bias, and justice impede effective mentoring of underrepresented students, faculty, and staff, including BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, PWD, first-generation college students, and others in the global majority? How do we arrive at a shared understanding of the definitions and praxis related to equity and racial and social justice, and what is their relevance to effective mentoring in academia? How could critical self-reflexivity about our own race, gender, class origin, and other systems of oppression improve mentoring for underrepresented students, faculty, and staff?

In this chapter, we share a few best practices for mentoring faculty, staff, and students from minoritized groups (with an emphasis on BIPOC, women, queer and trans individuals, PWD, and first-generation college students) to ultimately help our universities and academic disciplines benefit from the strategic advantage of justice, equity, accessibility, diversity, and inclusion (JEADI). We are particularly attentive to the value added by intersectionality to interrogations of systemic racism, specifically the dynamics of individual and institutional gendered racism in the form of anti-Blackness and their impact on the distribution of resources (Collins, 2009; Crenshaw, 1991; Dancy et al., 2018; Zambrana, 2018; Vargas & Jung, 2021).

We argue that successful mentoring is vital for making students, staff, and faculty feel that they belong, are respected, bring value, and are encouraged to thrive (Zambrana, 2018. In the pages that follow, we discuss (a) the vital necessity of mentoring to advance inclusive excellence; (b) mentors’ role in designing strategies for creating more inclusive educational and scholarly environments; (c) impediments to successfully mentoring BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ students and faculty; (d) common missteps in mentoring relationships; (c) cumulative disadvantage and what it means for junior faculty who overcome numerous challenges; (f) encouraging potential mentors to do the work to prepare to advise, support, and advocate for BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ students and faculty; (g) understanding best practices for mentoring within the context of higher education; and (h) lessons learned.

The Vital Necessity of Mentoring to Advance Inclusive Excellence

Building on the work of Franz Fanon (1963) and Lewis Gordon (2006), Reiland Rabaka (2010) has explained that our academic disciplines suffer critical decay due to a lack of intellectual diversity. This lack of diversity emanates from “institutional racism, academic colonization, and conceptual quarantining of knowledge, anti-imperial thought, and/or radical political praxis produced and presented by . . . ‘especially Black’ intellectual-activists” (Rabaka, 2010, p. 16). US and global Black scholarship is undercited across academic fields (Zerai et al., 2016). We quote Rabaka here, who notes that the intellectual works of Black scholars often do not appear in disciplinary canons. Instead of integrating the works of W. E. B. Du Bois into mainstream sociology, for example, if Du Bois is taught at all, his work often falls under the topic of “Black sociology.” Sometimes the ideas and creative works of Black scholars and artists are appropriated either on purpose or because of a lack of awareness on the part of white scholars whose work replicates ideas previously published by Black scholars without citing those scholars (Greene, 2008). At other times racism directly contributes to the muting of Black innovation (Rothwell et al., 2020). We add especially Black women intellectual-activists and others who occupy various intersectional identities and characteristics, as we explain below (Zerai, 2016, 2019).

Given these omissions and the deleterious impact on knowledge production, JEADI initiatives and perspectives are needed to benefit our educational and scholarly missions in higher education. This has not only been theorized, it has also been documented. From the work of social scientists, behavioral scientists, decision-makers, and organizational researchers, we know that diverse groups are more productive, creative, and innovative (Herring, 2009). Research has shown that diverse groups generate higher-quality ideas (McLeod et al., 1996; Loyd et al., 2013; de Vaan et al., 2015). And the level of critical analysis of decisions and alternatives is higher in groups exposed to minority viewpoints (Sommers, 2006; Loyd et al., 2013; van Dijk et al., 2017). It is thus vitally important for our campus representation to reflect the diversity of the world, United States, and communities where we live and work.

Diversity and inclusion foster innovation (Bell et al., 2011; Hofstra et al., 2020), and diversity and inclusion are synergistic.

Decision-making improves when teams embrace different points of view; independence of thought; and the sharing of specialized knowledge. . . . Diverse groups also do better on sophisticated problem-solving tasks than homogeneous groups because accommodating different experiences breaks down the risk of groupthink. . . . Groups that make the time to openly discuss conflict and that want to learn from all perspectives can reap the greatest benefits of diversity through the development of an inclusive culture. (McConahey & Vernon, 2014)

Educational institutions suffer turnover, missed opportunities, low morale, and loss of contributions when white, established faculty in positions of power and mentors overlook and underutilize the full potential of BIPOC, PWD, LGBTQIA+, students, staff, and faculty members and marginalize them. “At their best, diversity and inclusion efforts work together to cultivate an empathetic understanding in leaders and colleagues that allows them to value each other as individuals and as a whole people” (McConahey & Vernon, 2014).

Diversity without actually including the ideas and centering the realities of all colleagues and students is tokenism. We love it when our colleague, Dr. Kirsten Buick—chair, Africana Studies, professor at the College of Fine Arts at The University of New Mexico—says, “Diversity means we will be changed.” It is not enough to recruit talented faculty and students and make them just like you. Second, in order to operationalize the idea of being changed, it is imperative that established white middle-class continuing-generation college senior faculty members who occupy positions of power and privilege work with their colleagues to create an inclusive departmental, college, and university culture. This can mean different things in different settings. For example, it may (a) mean expanding the curriculum and enlarging the previously accepted contours of an academic discipline; (b) it can include cultural sharing, or accommodating employees who are caregivers; and (c) it can include changing the university and disciplinary missions in ways that embrace the community cultural wealth of groups that have been previously marginalized and it could even mean developing intersectional equity metrics (Yosso, 2005) and establishing accountability that corresponds to these metrics. Next, we discuss ways mentors can create more inclusive educational and scholarly environments.

Mentors’ Role in Designing Strategies for Creating More Inclusive Educational and Scholarly Environments

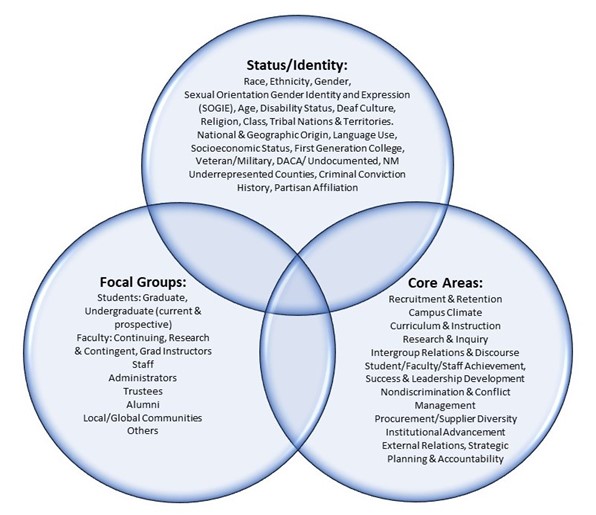

As systems-thinkers, professionals addressing JEADI design strategies for creating more inclusive educational and scholarly environments. It is important to be explicit at the outset about the community that we want to strengthen. The National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education (NADOHE) offers a three-dimensional model of higher education diversity (Worthington, 2012). We expand that definition in Figure 12.1. Constituency groups’ social identities and characteristics reflect the intersectionality of many social statuses and positions in systems of oppression and resistance, including race, ethnicity, class origin, parental educational attainment (including first-generation/continuing-generation college status), current socioeconomic status, gender, national and geographic origin, immigration status, sexual orientation and gender identity and expression (SOGIE), foster care experience, unsheltered/homeless status, disability status, religion, nativity, language use, tribal enrollment status, citizenship, veteran and military affiliation, DACA (deferred action for childhood arrivals) and undocumented individuals, rural areas and counties underrepresented in higher education within the states in which our universities are located, criminal conviction history, and political ideology.

Figure 12.1

Three Dimensional Model of Higher Education Diversity

Note. Adapted from three-dimensional model of higher education diversity. Adapted from “Advancing Scholarship for the Diversity Imperative in Higher Education: An Editorial,” by R. L. Worthington, 2012, Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5, p. 2. Copyright 2012 by the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education.

Recent calls for proposals from the National Science Foundation (NSF) bring attention to the critical importance of addressing intersectionality to promote institutional change (NSF, 2020).

For example, the NSF’s Increasing the Participation and Advancement of Women in Academic Science and Engineering Careers (ADVANCE) program requirements indicate, “All NSF ADVANCE proposals are expected to use intersectional approaches in the design of systemic change strategies in recognition that gender, race, and ethnicity do not exist in isolation from each other and from other categories of social identity” (NSF, 2020). Intersectionality or attention to the co-constitution of race, gender, class, and other axes of inequality as both analytically distinct and simultaneous systems of oppression/resistance in a given sociohistorical context is a powerful tool for making inequities visible and helping institutions of higher education create effective actions for advancing undergraduate student success (Collins & Bilge, 2016). Intersectionality is a way of understanding the world that makes visible “where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects. It’s not simply that there’s a race problem here, a gender problem here, and a class or LBGTQ problem there” (Crenshaw, 2017). Intersectionality provides tools to analyze the multiplicative and simultaneous operation of historic configurations of intersecting systems of oppression and their accompanying domains of power, privilege, and oppression at the structural, institutional, disciplinary, interpersonal, and hegemonic cultural levels (Collins, 2009). A few examples illustrate the relevance of intersectional perspectives to effective mentoring. To employ intersectionality, for example, the types of questions to consider include:

- Though a high percentage of women are gaining entry into jobs in the university, are women of color gaining the same types of promotional opportunities as white men—and are there salary discrepancies when they do? How can mentors operate as champions to promote greater levels of equity and justice to address these salary discrepancies where they exist?

- How are challenges of successful promotion and tenure amplified for women who also have a disability? What are ways that we can design mentoring efforts to support individuals who are both women and PWD? What does this mean for traditional tenure clocks?

- How about addressing the physical infrastructure and resources for our undergraduate students? Are these designed with women students who are also working mothers or single mothers in mind? How can mentors help their students to address such systemic barriers?

- What about class origin? How are the mentoring experiences of BIPOC first-generation college students different from BIPOC continuing-generation college students? As mentors, how can we learn to provide effective resources to promote the well-being and academic success of our first-generation college students?

We need to make sure that we are asking these kinds of questions, setting policy and practice, and planning for long-term solutions in ways that will facilitate responding to the unexpected. As noted by the NADOHE, these social characteristics can be found in various focal groups (as indicated by circle 2 in Figure 12.1). In fact, it is our goal to diversify the social identities represented in those focal groups and to promote their inclusion in core areas (as shown in circle 3 of Figure 12.1). An example relevant to first-generation college students and those who are immigrants is designing recruitment activities in multiple languages and focusing on families and communities—not just the individual.

Our goal is to create and foster campus climates that are welcoming and that promote cultural humility (among all faculty, staff, and students). Further, we wish to deliver a curriculum that teaches us about ourselves as well as to appreciate the culture of others, and include instruction that is culturally responsive. Inclusion extends to procurement practices that encourage the use of minority- and women-owned businesses. We want to encompass foundation work and advancement in culturally sustaining ways, as well as to promote engagement of alumni from diverse backgrounds. Finally, accountability must include intersectional metrics to assess JEADI performance goals. For example, institutions of higher education generally define equity using one-dimensional metrics, such as race, gender, first-generation college status, disability, or LGBTQIA+ status alone; yet intersectional metrics that consider the simultaneity of race-gender-first generation college status, disability, LGBTQIA+ as simultaneous social statuses in a given sociohistorical context is necessary for advancing equity (López et al., 2018).

Equity is the goal. We know that we have arrived at an equitable state when social identity and characteristics do not determine access, opportunity, and outcomes—and when there is total inclusion in all core areas noted in Figure 12.1 (Worthington, 2012).

Recruiting talented women, PWD, people of color, undocumented citizens (Vargas, 2018)[1], LGBTQIA+, international, or first-generation college students and faculty, inclusive of all other communities noted in Figure 12.1 (hereafter referred to as “BIPOC, PWD, LGBTQIA+”) may require rethinking traditional admissions, assessment, hiring, and mentoring strategies, and research shows it is worth the effort (Herring, 2009; McConahey & Vernon, 2014; Williams, 2000; Springer, 2004a, 2004b; AAUP, 2000). In fact, it is not about just going out and recruiting individuals from minoritized groups. As senior faculty and staff who are often responsible for making these admissions and hiring decisions, it is important that we do the preparatory work so that we will be able to see the promise of potential recruits; handle recruitment processes in diversity-aware ways that are balanced with cultural humility; and finally, after admitting students or hiring faculty from one or more minoritized groups, are prepared to mentor our new students and colleagues in ways so that we do not reproduce academic woundedness (as defined by McIver, 2021; Neal-Barnett, 2003). In fact, the goal is to mentor students and colleagues and provide necessary resources and support so that they flourish in their academic and scholarly pursuits.

We will therefore review some impediments to successful mentoring before moving on to the discussion of best practices in mentoring that keeps JEADI at the forefront.

Impediments to Successfully Mentoring BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ Students and Faculty

One impediment to inclusion today is implicit bias (Jackson et al., 2014). Faculty members are encouraged to unveil their own implicit biases that we may bring to our daily tasks, decision-making, collective work, and mentoring and evaluation of peers and students that might form barriers to a welcoming climate. According to researchers who have produced the Harvard Implicit Associations tests (https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html), several implicit associations affect our mental processing. Some implicit associations include automatic preference for thin people relative to overweight people; automatic preference for heterosexual relative to LGBTQIA+ people; assumptions that images held by Black individuals are weapons, relative to assumptions that images held by white individuals are harmless; automatic preference for light skin relative to dark skin; the automatic relative link between family and females and between career and males; and many more (see Appendix 1 for a list).

While the Harvard Implicit Associations tests are an excellent start for this journey, once mentors have a sense of their implicit associations, they are in a better position to challenge them and to employ proven strategies to diminish their impact. There are a number of evidence-based behavioral strategies (Carnes et al., 2015). Here are four:

- Identify and intentionally replace stereotypes with accurate information;

- determine hiring criteria before assessing candidates;

- take your time to focus on specific information about a colleague to prevent group stereotypes from leading to potentially inaccurate assumptions; and

- use positive counter-stereotypic imaging by creating and taking advantage of opportunities for contact with counter stereotypic exemplars (e.g., meet with a senior Latina botanist to discuss her future plans and learn more about her route to success).

Finally, we can expand our repertoires (e.g., by reading the work or listening to podcasts from BIPOC, women, LGBTQIA+, and PWD colleagues within your discipline) so we can absorb novel concepts and tools and begin to understand lived experiences, both of which will enable the growth of cultural humility, which has been shown to enhance commitment to equity and be the first step to creating inclusive work environments (DallaPiazza et al., 2018).

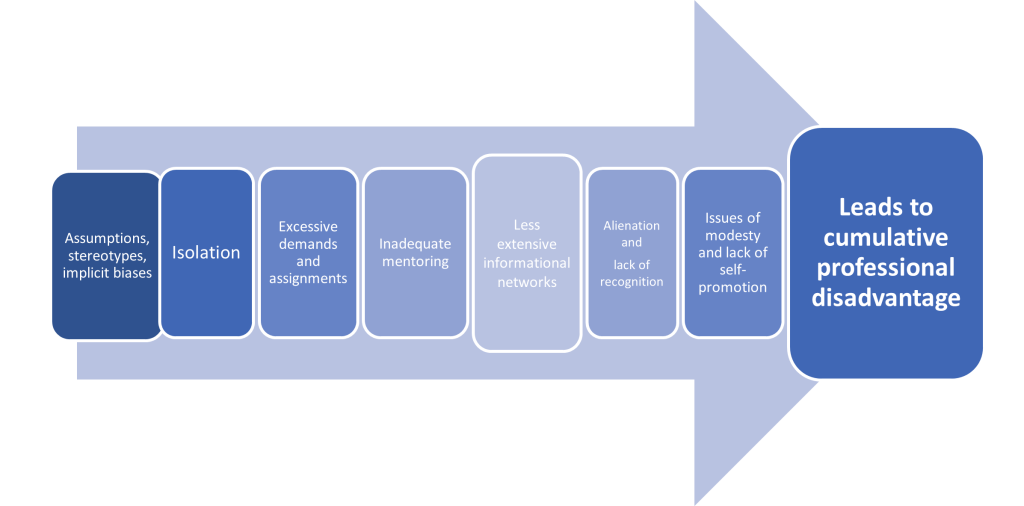

Research shows that when we do not take the time to learn about our biases and attenuate their effects, this can have consequences within our individual spheres of influence, as well as systemically. The impact of implicit and explicit bias shows up with regards to the effectiveness of our letters of recommendation (Madera et al., 2018), assessments of students’ academic performance (Boysen & Vogel, 2009), fewer citations of women’s and BIPOC scholarship (Dion et al., 2018; Chakravartty et al., 2018), appraisal of faculty members’ scholarship for promotion and tenure (Deo, 2018; Fang et al., 2000; Lisnic et al., 2019; Matthew, 2016; Moody, 2010), or choices of finalists among job applicants (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012; Player et al., 2019). Recognition of our own implicit biases is just a start. Bias is not just an individual phenomenon. It is also structural and is visible as discrimination. The next impediment to recruiting and mentoring talented students and faculty is the lack of recognition of the possible cumulative professional disadvantages that may result from implicit bias and other systemic barriers (as noted by Reade [2015]; see Appendix 2). Awareness of these roadblocks can help us begin to remove these barriers to finding prospective students and faculty whose unique perspectives could potentially transform our departments, disciplines, and even academia itself. Below, we enumerate the following three potential sources of implicit bias: (a) letters of recommendation, (b) gender stereotypes, and (c) jobs and promotions for BIPOC scientists.

Letters of Recommendation

Rice University has shown that letters of recommendation for BIPOC and non-BIPOC women applying for graduate programs and positions have more doubt raisers and are more likely to refer to them as students (even when the applicant is applying for a faculty position), and are more likely to mention their family responsibilities (see https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2018/06/180607133639.htm). Senior faculty may therefore wish to revisit letters of recommendation written on behalf of their mentees, and hiring and evaluation committees may want to take these facts into account when evaluating prospective women students and faculty or considering faculty for promotions.

Gender Stereotypes

Research shows that hiring officials are affected by pervasive gender stereotypes, unintentionally downgrading the competence, salary, and mentoring of a female applicant compared with an identical male applicant. In STEM, a study with a broad, nationwide sample of biology, chemistry, and physics hiring committees evaluated application materials of scientists for a laboratory manager position (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012). The application materials were exactly the same. The only difference in the two applications reviewed was the gender of the applicant. Hiring officials rated the applicant’s competence, amount of mentoring they would offer, and likeability.

Both female and male search committee members judged male applicants to be more competent, more hirable, and more capable of receiving mentoring than female applicants. Mirroring other research, ratings of likeability were higher for the females relative to males; these patterns reflect common stereotypes that men are perceived to be more competent and women more likable. However, liking the female applicant more than the male applicant did not translate into positive perceptions of her composite competence or material outcomes in the form of a job offer, an equitable salary, or valuable career mentoring. These findings underscore the point that hiring officials were affected by pervasive gender stereotypes, unintentionally downgrading the competence, salary, and mentoring of a female student compared with an identical male student.

Jobs and Promotions for BIPOC Scholars

A study by Stanford University researchers provides evidence of the diversity-innovation paradox in academia that the research innovations women and BIPOC scientists introduce are devalued when it comes to decisions about hiring and promotion. It offers extensive evidence that women and racial minorities introduce scientific novelty at higher rates than white men across all disciplines, but they are less likely to benefit—either through sought-after jobs or respected research careers. The findings were published on April 14 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (Hofstra et al., 2020). Now that we have reviewed impediments to successfully mentoring minoritized students, faculty, and staff we will turn to common missteps in mentoring relationships.

Common Missteps in Mentoring Relationships

Common missteps in mentoring relationships include senior faculty members’ fixed mindsets (Quay, 2017) in their approaches toward students and junior faculty from various minoritized groups; deficit perspectives about students’ and junior faculty members’ intellectual contributions; gender-, SOGIE-, disability-, class-, and color-evasive perspectives on the part of senior faculty, and their resultant lack of intervention when students and junior faculty are targets of microaggressions and bullying; insensitive and triggering comments by senior faculty; and lack of critical reflexivity among senior faculty who have been assigned to serve as mentors to BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ students, staff, and early-career faculty.

We explain missteps by offering a scenario that involves a junior faculty member who is a Native American woman and is assigned to a white male mentor (as developed by Culbreath et al., 2020). The mentor immediately assumes she will not be successful in their department because she, against his recommendation, is pursuing an interdisciplinary community-based research topic. At the end of her first year as an assistant professor, he indicates to the annual review committee that she “just doesn’t have what it takes” to achieve tenure. He apparently assumes this despite her outstanding publication record and her recent success in obtaining substantial external funding.

In this example, the white male senior faculty member cannot effectively mentor BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ students or junior faculty if he believes in fixed mindsets. If this senior faculty member has effectively mentored white junior faculty in the past, even if they have simply followed in his footsteps, replicating his area of expertise within the discipline, it appears that he does believe in growth mindsets for white faculty. If such a senior faculty member reverts to a fixed mindset when mentoring a Native American woman who is a junior faculty member, for example, then he is displaying clear bias toward his colleague. His framing of the Native American woman assistant professor and her interdisciplinary community-based research from a deficit perspective discounts the intellectual contributions of this Native American woman.

In the case of senior faculty displaying bias, department chairs must be given the tools and presented with the expectation that they will step in and interrupt the bias, and even consider reassigning the junior faculty to a mentor who is willing to challenge their own biases. Failure to do so would be an example of color-evasive racism. “Color-evasiveness . . . acknowledges that to avoid talking about race is a way to willfully ignore the experiences of people of color,” it is a “refusal to address race, and its corollary racism” (Annamma, 2017, p. 157). Color-evasive racism in mentoring relationships occurs when white faculty do not affirm the racialized experiences of students or colleagues who are people of color.

The Association of Public and Land-Grant Universities (APLU) indicates that “[academic] environments . . . can be ‘motivating’ or ‘demotivating’ in their design. We can sustain people’s natural drive to learn [and become experts in their fields]—or we can undermine it” (Quay, 2017). In our theoretical example, by assigning the Native American faculty member to this so-called mentor, the department chair is creating a demotivating environment for her. This could result in a number of deleterious effects, including that she may question her fit in the department or at the university despite other early career accomplishments. This discussion is well informed by exploring the cumulative disadvantage experienced by faculty, staff, and students from minoritized groups.

Cumulative Disadvantage and What it Means for Junior Faculty who Overcome Numerous Challenges

As shown in the figure in Appendix 2 (Reade, 2015), women, BIPOC, PWD, LGBTQIA+, and first-generation college faculty often need to overcome cumulative disadvantages to get through graduate school, become recognized as worthy of being added to the pool of finalists, and become hired as tenure-system faculty (Whitaker & Grollman, 2019; Buenavista et al., 2022). For example, BIPOC faculty have to publish at a higher rate compared to white faculty to be considered worthy of being hired for the same positions or promoted at the same rate, as shown in multiple academic disciplines (Fang et al., 2000; Matthew, 2016; Deo, 2018). Researchers at Stanford University have shown BIPOC graduate students and postdocs who are applying for junior faculty positions and attempting to publish are not recognized for their novel approaches and ideas (Hofstra, et al., 2020). Minoritized faculty surmount additional hurdles to advance in their fields and prepare to submit dossiers for tenure, promotions, and beyond. BIPOC faculty, for example, face time taxes and are pressured to spend more hours in service (relative to time spent teaching and researching). Furthermore, extra time preparing for class is required for many BIPOC faculty who are not considered to be credible by their white students (Hendrix, 1998). Such time investments are especially required for BIPOC women faculty, to address and attempt to head off bias and racialized sexism from white and even sometimes BIPOC students who are more apt to challenge and behave disrespectfully toward women of color faculty (Hendrix, 1998, 2020; Stolzenberg et al., 2019).

Nonwhite faculty members report that to be seen as “legitimate” scholars, they must do more emotional work interacting with their colleagues around research. Almost three-quarters of Black, Asian and Latinx professors reported “feeling a need to work harder than their colleagues to be seen as legitimate scholars,” compared to less than half of white professors. The work involved in supporting and mentoring students, legitimizing one’s research, and navigating racial microaggressions is part of the “invisible labor” that most colleges and universities do not recognize in the tenure and promotion process. (Rucks-Ahidiana, 2019; Zamudio-Suarez, 2021)

As noted above, a number of scholarly articles document these challenges (Dion et al., 2018; Chakravartty et al., 2018; Deo, 2018; Fang et al., 2000; Lisnic et al., 2019; Matthew, 2016; Moody, 2010). The good news is that anyone who has overcome even a sampling of these obstacles brings a wealth of experience and inclusive excellence to one’s department, university, and academic discipline. This is a tremendous gift to all students and faculty in your university, and especially students of color. Minoritized faculty have faced many of these challenges during their years as graduate students, postdocs, and junior faculty and are often prepared to mentor differently. They often understand the importance of seeing URM students and faculty colleagues from the standpoint of growth mindsets and do not assume fixed innate intelligence and ability, that either you “have it,” or you do not. Junior faculty who see URM students and all students from the perspective of growth mindsets recognize that we all learn and grow and that it is important for faculty to provide students the tools they need and contribute to motivating environments in which to grow. Research has shown that students’ growth mindsets flourish when we change the messages we send to them as educators (Quay, 2017). One reason that URM faculty serve as excellent mentors to URM and all students is that they are likely to offer crucial mentoring and professional development opportunities to their students. Finally, BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ mentors and supervisors who have overcome various barriers can help mentor their students and colleagues and build a roadmap for success that avoids many pitfalls. While it is helpful for mentors to understand these cumulative disadvantages, it is equally important for mentors to enhance their skills as mentors.

Encouraging Mentors to do the Work to Prepare to Advise, Support, and Advocate for BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ Students and Faculty

As leaders and mentors, we can actively employ strategies to attenuate the impact of bias and create more inclusive learning and scholarly environments in higher education. Two of these strategies include cultural humility and theorizing academic woundedness.

Cultural Humility

Culturally responsive teaching, also called culturally relevant teaching, is a pedagogy that recognizes the importance of including students’ cultural references in all aspects of learning (Ladson-Billings, 1995). It builds on individual and cultural experiences and prior knowledge. We posit that culturally responsive mentoring recognizes the importance of including students’ cultural references in all aspects of mentoring and must build on individual and cultural experiences and mentees’ prior knowledge in order to strengthen our students’ sense of identity, promote equity and inclusivity in mentoring practices, and support the holistic academic success and wellness of all students, and especially for students who are BIPOC, PWD, & LGBTQIA+, and so on. Culturally relevant mentoring is just the first step.

Culturally sustaining (CS) mentoring goes a step further and (drawing from Django Paris’s work on CS pedagogy) exists wherever mentors encourage students’ and scholars’ academic work that “sustains the lifeways of communities who have been and continue to be damaged and erased through schooling” (Paris, 2012, p. 93) and higher education. As such, CS mentoring “explicitly calls for our educational institutions to be a site for sustaining—rather than eradicating—the cultural ways of being of communities of color” (Paris, 2012, p. 93) and for mentors to serve as advocates and accomplices in this work.

Finally, once mentors become aware of and begin praxis around culturally relevant, responsive, and sustaining mentoring, the most important place of growth is for mentors to embrace cultural humility (Zerai, et al, in press). In response to the concept of “cultural competence,” cultural humility is the “ability to maintain an interpersonal stance that is other-oriented (or open to the other) in relation to aspects of cultural identity that are most important to the [mentee]” (Hook et al., 2013, p. 2). As Hook et al. explain, cultural humility requires:

- lifelong commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique;

- attention to fixing power imbalances (in the classroom, within our disciplines, and in our academic departments); and

- developing partnerships with people and groups who advocate for others.

The gold standard for effective mentoring includes a demonstrated commitment to cultural humility. And critical reflexivity that considers complex inequalities (Boveda & Weinberg, 2020) promotes cultural humility. It is only with this stance that we put ourselves in true service of our students and others whom we mentor and that we approach them with mutual respect and with the recognition that the mentoring relationship is a space of reciprocity, where we enter with the expectation that we will learn from each other.

Martinez-Cola (2020) offers a number of examples of cultural humility in her description of mentors who are allies. For example, she notes that allies have the ability to recover from a disagreement. In her words,

Disagreements are part of every relationship. Collectors are devastated when confronted with their bias, implicit or otherwise. I almost hesitate to point out a Collector’s problematic words or behaviors because I know they will respond as if their whole world has just collapsed. DiAngelo (2018) describes this response as “White fragility.” What is worse is that they will expect me to help them feel better about themselves and affirm their imagined place in my world. An Ally, on the other hand, apologizes, uses the experience for self-reflection, and then puts in the work to self-educate. The onus for growth is on them, not me. An Ally also knows when to push back and when to support, when to question and when to validate. The most important aspect of a relationship with a mentor who is an Ally is trust. They have earned a [BIPOC student’s] trust with their consistency and humility. (Martinez-Cola, 2020, p. 38)

Theorizing Academic Woundedness

Though the experiences of academic woundedness have been ubiquitous, especially for individuals who are BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA +, discussions of this phenomenon are only recently entering the academic literature (Neal-Barnett, 2003, 2020; McIver, 2020, 2021; Lee, 2021). In a 2021 survey, we learned of multiple examples of woundedness resulting from experiences of racial and intersectional microaggressions (RIMAs), often perpetrated by faculty, staff, advisors, and others serving as mentors to BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ graduate, professional, and undergraduate students. UNM Student Counseling Center director, Dr. Stephanie McIver, explains that the foundation of academic woundedness comes from the concept of psychological woundedness (2020). Drawing from the work of Ivey and Partington (2014), McIver indicates that woundedness is the residual impact of adverse experiences and psychic conflicts. Further, McIver helps us to understand that one of the negative outcomes from woundedness is rumination. Quoting Julianne Malveaux, McIver reminds us that microaggressions are “slights that grind exceedingly small.” One reason such slights stick with those of us who experience microaggressions daily (Lewis et al., 2019) is that we sometimes ruminate on the intention of the individual’s offensive actions or words. “Ruminating thoughts are excessive and intrusive thoughts about negative experiences and feelings. A person with a history of trauma may be unable to stop thinking about the trauma, [and,] for example, . . . may persistently think negative, self-defeating thoughts” (Villines, 2019). In our 2021 survey results, we found evidence that students who have been targets of RIMAs experienced negative impacts that are consistent with rumination. For example, the majority of BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ students report that they lost interest in daily activities or coursework, felt a lack of energy, were less confident, had difficulty concentrating, and felt restless, subdued, or had trouble sleeping as a result of being targeted by RIMAs (Zerai et al., 2021).

Further, the primary concern of BIPOC, students with disabilities, and queer and trans students in our survey is the perceived inaction of authorities—staff, department chairs, faculty, advisors, and graduate assistants who observe RIMAs and say and do nothing. Therefore, mentors can exert a tremendous amount of power and influence on behalf of their students and colleagues when they serve as upstanders. Students rightly expect authority figures to serve as upstanders who bear witness to RIMAs and are courageous enough to interrupt them.

We offer upstander workshops in which we invite faculty to practice interrupting microaggressions. In one of our skits, we depict a Black medical student who asks for guidance from a Latina nurse who dismisses the student’s concerns about a patient who used a racial slur when referring to the medical student. The mentor responds, “As women we are strong. And you will need to be a bit more thick skinned if you want to succeed in the medical profession.” Our skit ends with a spotlight on an Asian American attending physician, who clearly overhears the exchange. Our faculty upstanders-in-training offer a number of ways to respond so that the student’s experience is validated and her education is supported holistically. Faculty upstanders recommend that the attending physician can move from a passive bystander to an active bystander (or upstander), by stepping into the conversation. In this role, the attending physician has a number of options. They can offer to report the incident to the university’s ethics, compliance and equal opportunity office; they can share the link for reporting disciminatory incidents with the student; they can also communicate that racial slurs are not to be tolerated by physicians, staff, or patients and point to hospital policies to this effect. Further, if appropriate signage indicating the requirement for respectful interactions with hospital staff is not currently present in treatment and waiting rooms, the attending physician can contact the hospital’s communications team to request that this signage be posted. Actions such as these can help to validate the experiences of BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and PWD students, staff, and faculty and disrupt patterns of rumination and possible continued negative effects, such as academic woundedness.

Once prospective mentors learn more about implicit biases, cultural humility, and academic woundedness, they are ready to delve into best practices for mentoring individuals from minoritized groups.

Understanding Best Practices in Mentoring: Resources for Higher Education

In this section, we discuss resources from the National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity, National Research Mentoring Network, and researchers promoting intersectionally conscious collaboration in mentoring. The National Center for Faculty Development and Diversity (NCFDD) has created a mentoring map (see mentoring map, https://ncfdd-production-file-uploads.s3.amazonaws.com/media/399d28e3-a382-44b1-8bfa-4394ad6148d5-MentoringMap-Interactive.pdf). NCFDD founder Kerry Ann Rockquemore has published a mentoring series in Inside Higher Ed (2013) in which she explains that the old-school “guru” style of mentoring is insufficient for today’s students and junior faculty. Instead, she encourages the use of a mentoring map that invites graduate students, faculty, and other academic professionals to extend their network of mentors (see Chapter 27 for more on networked mentoring). In today’s ever-changing landscape, and with greater attention to work-life balanc—especially important for BIPOC and all women, individuals who are first-generation college status, PWD, LGBTQIA+ folks, and parenting students or faculty—it is unusual for one mentor to provide all of the support needed.

Furthermore, in the academic literature, there is a distinction between different types of mentors. There we see mentors can range, for example, from role models, coaches, advocates, and champions, to sponsors, and beyond. Sponsors who provide specific strategic opportunities to an individual at a particular time are crucial (see Chapter 1 of this volume; also see Martinez-Cola, 2020).

There are several resources to grow the mentoring capacity of faculty. These include the NCFDD, which provides a six-part series on effective mentoring, the National Research Mentoring Network (https://nrmnet.net/), and the Center for the Improvement of Mentored Experiences in Research. (CIMER, https://wcer.wisc.edu/About/Project/2359). These networks that provide “train the trainer” models are excellent because they teach mentoring through skill-building. Further, they provide useful resources, such as sample contracts that academic advisors, research advisors, principal investigators (PIs), and chairs can establish with dissertation students so that expectations are clear concerning coauthored publications, turn-around time for providing feedback to dissertation chapters, and the like.

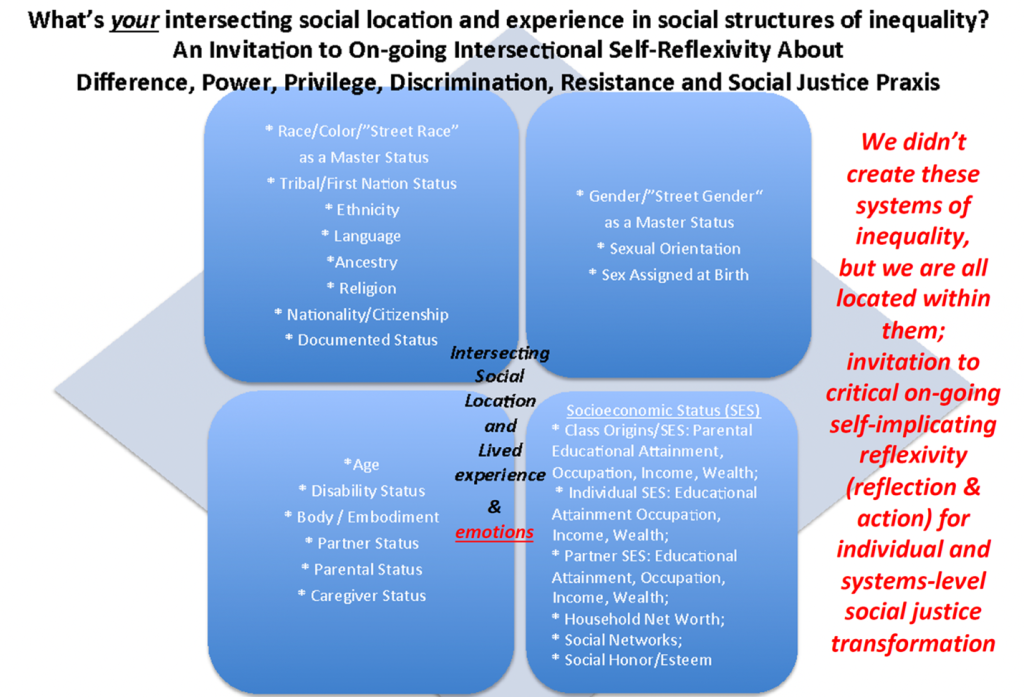

At its purest level, a mentoring relationship is a type of collaboration. Boveda and Weinberg (2020, p. 481) offer a protocol that provides a strategy for what they call “intersectionally conscious collaboration” to “encourage reflection on marginalized and privileged identities on how these influence educational and professional experiences.” Such tools could be useful for mentors. In reflecting on social and spatial location, mentors may pose questions that result in “reflection on marginalized as well as privileged identities, and on how these influence(d) educational and professional experiences.” This information may be helpful to cocreating “professional roles and responsibilities, . . . to assess how educators’ identities may influence the experiences of students.” This information sets the stage for collaborators in a mentoring relationship who can build from this base of knowledge and discussions about the respective goals of mentor and mentee to negotiate expectations on the basis of a shared understanding of respective strengths.

An Example

Dr. López offers an example of intersectional inquiry that yields effective mentoring and collaboration. She starts with an intentional conversation that invites the mentor and mentee to share their respective positionalities, experiences, academic background, and hopes for their intended scholarly pursuits (see Appendix 3 as an example of a tool for cultivating a critical reflexive praxis centered on intersectionality). She always asks, “Is there anything else you would like me to know.” This could be done verbally or in writing to accommodate introverted students. Sharing the answers to these questions may be the beginning of a productive and collaborative relationship between a mentee and mentor.

The following is a composite reflection of the mentoring meetings that Dr. López had with numerous BIPOC students who seek her mentorship for pursuing doctoral studies:

Dr. López: Thank you for reaching out. I find that it is powerful to start a mentoring relationship by sharing a bit about our differences and similarities in our identities in our positionalities in systems of inequality. I’d like to start with sharing a bit about myself. I am a U.S.-born Black Latina. My first language is Spanish. My parents are Dominican immigrants who worked in the garment industry sweatshops in Lower Manhattan in New York City for most of their lives. I grew up in New York City public housing and attended de facto segregated public schools. I participated in upward bound, a federal program for those who are first in their families to earn a college degree. I earned a BA in Latin American Studies from Columbia College, Columbia University, and earned a doctorate in sociology from City University of New York because I want to do research that I hope makes a difference for communities like the one I grew up in. I’ve been teaching at UNM for over 20 years. I am married to a Brown-skinned Chicano man artist and gallery curator who has deep roots in NM. We have two adult daughters. Now I invite you to think about your social and spatial location and share any parts of your identity that you think will help us work well together. Please only share information you are comfortable sharing.

Lucia Rodriquez’s (composite undergraduate mentee) response: Gracias profe! Thank you for sharing your background. Español es mi primer idioma también! [Spanish is also my first language]. I love that I can speak to you in Spanish. I actually shared your TED en Español talk about the Census with my mother. I am a white Latina or Whitina—Mexican American born and raised in the U.S. Sometimes people are shocked to learn that I’m Latina because, according to them, “I don’t look Latina.” I also identify as LBTQIA+, and I am not out to my family. My mom is an educational assistant, and she earned a GED. My father only when to middle school, and he is undocumented. I want to go to graduate school so I can become a professor and teach at the university. I want to do research on the health consequences of racism for undocumented immigrants.

This sharing allows for clarification in the ways that structural inequalities may be different for my mentee and myself. While Lucia and Dr. López could say that they are both the children of immigrants, Spanish is their first language, and they have similar class origins and ethical and political commitments, they also had major differences in terms of citizenship status, racial status, LGBTQIA+ status, and ethnicity (Zambrana, 2018; Yuval-Davis, 2011). Baca Zinn and Zambrana (2019) state:

We caution that “Latino/Latina” as a social construct must be problematized, that it is complicated by differences in national origin, citizenship, race, class, and ethnicity and by the confluence of these factors. An intersectional approach seeks to reveal and understand how they shape social experience. (p. 678)

Dismantling the myth of a homogenous Latinx experience for Latinx undergraduate students, graduate students, staff, or faculty is important for practicing inclusive mentoring. An intersectional approach to mentoring includes not adding oppressions (race + gender + class origin + LGBTQIA+ status) to assess who is most oppressed but rather understanding our very different experiences with systems of oppression (Bowleg, 2008). To round out the discussion in this chapter, we next discuss some lessons learned.

Lessons Learned

So, you want to improve your mentoring? Below are some notes on lessons learned.

- At the individual level, practice ongoing and lifelong critical reflexivity. Part of this is critical reflection on your own positionality in grids of power (race, gender, class as in your first-generation college status, disability, citizenship, LGBTQIA+ status, etc.) and considering how that influences your approach to mentoring. This does not mean that you cannot be an effective mentor if you differ from your mentees, but it does mean that you are consciously taking all those things into consideration in creating a productive collaboration.

- At the institutional, unit, and department level, challenge deficit narratives and approaches to marginalized and underrepresented communities. When you hear discourses about equity and excellence as mutually exclusive or discussions about “fit” or “at-risk” students, invite your colleagues to center the cultural wealth of staff, students, and faculty. Ask what it would mean if we acknowledge that students who are parents, have family responsibilities, or come from minoritized communities possess experiential knowledge that can improve our institutions, disciplines, and services in the university (Yosso, 2005). What would it mean if we eschewed race-, color-, class-, gender-, sexuality-, disability-, and power-evasive narratives in our mentoring and support of students by explicitly engaging in critical reflexivity, not as individual supervisors or faculty, but rather as whole departments across time?

- At the university-wide level, create a community of practice, a convergent space, with colleagues across different sectors (faculty and staff governance, high-level administrators) for sharing strategies and approaches for mentoring that work with students who are what Elisa Sanchez, lifelong activista and education subcommittee member of the New Mexico Governor’s Advisory Racial Justice Council, calls “at- promise” (here we challenge the notion of “at-risk”), but are often overlooked in mentoring approaches. Create accountability structures when units fail to engage in these conversations and refuse to become a part of the solution. Discuss how you plan to create intentional mentoring experiences that challenge business as usual and one-size-fits-all mentoring approaches. Question your assumptions, and imagine the possibilities when embracing mentoring with renewed purpose and clarity as we harmonize our mentoring practice from the individual to the department and university levels. Ask yourself, your colleagues, and university administrators, how would we know we have been successful in transforming our mentoring praxis (action and reflection)?

Conclusion

In this chapter, we have described the vital necessity of mentoring to advance inclusive excellence, mentors’ role in designing strategies for creating more just educational and scholarly environments, and impediments to successfully mentoring BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ students and faculty and common missteps in mentoring relationships. Though minoritized groups often experience cumulative disadvantage that has major consequences for their success as students, staff, or faculty, when members from these groups have overcome these numerous challenges, they are poised to contribute to universities and disciplines in multiple and unique ways.

We encourage all prospective mentors to do the work to prepare to mentor BIPOC, PWD, first-generation college status, and LGBTQIA+ students, staff, and faculty. We posit that the gold standard for effective mentoring must include a demonstrated commitment to cultural humility. We point readers to national resources to improve their mentoring. Finally, we share examples, including how intersectional inquiry yields effective mentoring and collaboration by applying Boveda and Weinberg’s (2020, 2022) intersectionally conscious collaboration to mentoring.

In the future, we recommend the importance of developing mentors’ cultural humility, their facility with strengths-based perspectives, fortifying their growth mindsets in their approaches to students, staff, and early career faculty, and learning to appreciate the cultural wealth of BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ colleagues. In the end, high-impact strategies for senior faculty mentors include promoting culturally sustaining pedagogy, mentoring and research, and developing critical self-reflexivity so that they actively challenge their own biases. At the institutional level, ethical accountability can be practiced through setting department-, college-, and university-level metrics for annual reviews, promotions, and special awards that reward senior faculty for their improvements in mentoring students, staff, and colleagues who are BIPOC, PWD, and LGBTQIA+. We recommend future research focused on case studies of academic departments making changes across time to measure the effectiveness of mentoring strategies guided by the principles of inclusive excellence. This would include interviews with students, staff, and faculty who are BIPOC, first-generation college status, PWD, and LGBTQIA+ to focus on their experiences with mentors in order to identify their perspectives concerning successful mentoring as well as their recommended areas for improvement.

References

American Association of University Professors (AAUP). (2000). Does diversity make a difference? Three research studies on diversity in college classrooms. American Council on Education and American Association of University Professors.

Annamma, S. A., Jackson, D. D., & Morrison, D. (2017). Conceptualizing color-evasiveness: Using dis/ability critical race theory to expand a color-blind racial ideology in education and society. Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(2), 147–162, DOI: 10.1080/13613324.2016.1248837

Baca Zinn, M., & Zambrana, R. E. (2019). Chicanas/Latinas advance intersectional thought and practice. Gender & Society, 33(5), 677–701.

Bell, S. T., Villado, A. J., Lukasik, M. A., Belau, L., & Briggs, A. L. (2011). Getting specific about demographic diversity variable and team performance relationships: A meta-analysis. Journal Manage, 37, 709–743.

Boveda, M., & Weinberg, A. E. (2020). Facilitating intersectionally conscious collaborations in physics education. The Physics Teacher, 58(7), 480–483.

Boveda, M., & Weinberg, A. E. (2022). Centering racialized educators in collaborative teacher education: The development of the intersectionally conscious collaboration protocol. Teacher Education and Special Education, 45(1), 8–26.

Bowleg, L. (2008). When Black + lesbian + woman ≠ Black lesbian woman: The methodological challenges of qualitative and quantitative intersectionality research. Sex Roles, 59(5), 312–325.

Boysen, G. A., & Vogel, D. L. (2009). Bias in the classroom: Types, frequencies, and responses. Teaching of Psychology, 36(1), 12–17.

Buenavista, T. L., Dimpal, J., & Ledesma, M. C. (Eds.). (2022). First generation faculty of color: Reflections on research, teaching, and service. Rutgers University Press.

Carnes, M., Devine, P. G., Manwell, L. B., Byars-Winston, A., Fine, E., Ford, C. E., Forscher, P., Isaac, C., Kaatz, A., Magua W., Palta M., & Sheridan, J. (2015). Effect of an intervention to break the gender bias habit for faculty at one institution: a cluster randomized, controlled trial. Academic Medicine: Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 90(2), 221.

Chakravartty, P. R., Kuo, V. G., & McIlwain, C. (2018). #CommunicationSoWhite, Journal of Communication, 68(2), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1093/joc/jqy003

Collins, P. H. (2009). Black feminist thought. Routledge.

Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Wiley & Sons.

Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299.

Culbreath, K., Margaret M., Pereda, B., & Sood, A. (2020). Case discussions: MODULE 5 understanding diversity among mentees [Faculty mentoring training]. University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center.

DallaPiazza et al., 2018 Exploring Racism and Health: An Intensive Interactive: Session for Medical Students. MedEdPORTAL, 2018. 14. https://www.mededportal.org/doi/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.10783

Dancy, T. E., Edwards, K. T., & Earl Davis, J. (2018). Historically white universities and plantation politics: Anti-Blackness and higher education in the Black Lives Matter era. Urban Education, 53(2), 176-195.

Deo, M. E. (2018). Intersectional barriers to tenure (Thomas Jefferson School of Law Research Paper No. 3729675). University of California Davis Law Review, 997–1037. https://www.ssrn.com/abstract=3729675

De Vaan, M., Stark, D., & Vedres, B. (2015). Game changer: The topology of creativity. American Journal of Sociology, 120, 1144–1194.

Dion, M., Sumner, J., & Mitchell, S. (2018). Gendered citation patterns across political science and social science methodology fields. Political Analysis, 26(3), 312–327. doi:10.1017/pan.2018.12

Fang, D., Moy, E., Colburn, L., & Hurley, J. (2000). Racial and ethnic disparities in faculty promotion in academic medicine. Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), 284(9), 1085–1092. doi:10.1001/jama.284.9.1085

Greene, K. J. (2008). Intellectual property at the intersection of race and gender: Lady sings the blues. American University Journal of Gender, Social Policy & the Law, 16(3), 365–385.

Hendrix, K. G. (1998). Student perceptions of the influence of race on professor credibility. Journal of Black Studies, 28(6), 738-763.

Hendrix, K. G. (2020) When teaching fails due to third-party interference: a Blackgirl Warrior’s story, Communication Education, 69:4, 414-422, DOI: 10.1080/03634523.2020.1804067

Herring, C. (2009). Does diversity pay? Race, gender, and the business case for diversity. American Sociological Review, 74(2), 208–224.

Hofstra, B., Kulkarni, V. V., Galvez, S. M. N., He, B., Jurafsky, D., & McFarland, D. A. (2020). The diversity–innovation paradox in science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(17), 9284–9291. DOI:10.1073/pnas.1915378117

Hook, J. N., Davis, D. E., Owen, J., Worthington Jr, E. L., & Utsey, S. O. (2013). Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal of counseling psychology, 60(3), 353.

Ivey, Gavin, and Theresa Partington. “Psychological woundedness and its evaluation in applications for clinical psychology training.” Clinical psychology & psychotherapy 21.2 (2014): 166-177.

Jackson, S. M., Hillard, A. L., & Schneider, T. R. (2014). Using implicit bias training to improve attitudes toward women in STEM. Social Psychology of Education, 17(3), 419–438.

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American educational research journal, 32(3), 465-491.

Lee, J. K. J. (2021). Pedagogies of woundedness: Illness, memoir, and the ends of the model minority. Temple University Press.

Lewis, J. A., Mendenhall, R., Ojiemwen, A., Thomas, M., Riopelle, C., Harwood, S. A., & Browne Huntt, M. (2021). Racial microaggressions and sense of belonging at a historically white university. American Behavioral Scientist, 65(8), 1049–1071.

López, N. (2019). “Working the cracks” in academia and beyond: Cultivating “race” and social justice convergence spaces, networks, and liberation capital for social transformation in the neoliberal university. In M. C. Whitaker & E. A. Grollma (Eds.), Counternarratives from women of color academics: Bravery, vulnerability and resistance (pp. 33–42). Routledge.

López, N., Erwin, C., Binder, M., & Chavez, M. J. (2018). Making the invisible visible: Advancing quantitative methods in higher education using critical race theory and intersectionality. Race Ethnicity and Education, 21(2), 180–207.

Loyd, D. L., Wang, C., Phillips, K. W., & Lount, R. (2013). Social category diversity promotes premeeting elaboration: The role of relationship focus. Organization Science, 24, 757–772.

Martinez-Cola, M. (2020). Collectors, nightlights, and allies, oh my! White mentors in the academy. Understanding & Dismantling Privilege, 10(1), 61–82.

Matthew, P. (2016). Written/unwritten: Diversity and the hidden truths of tenure. The University of North Carolina Press. http://muse.jhu.edu/book/48236

McConahey, E., & Vernon, J. (Eds.). (2014). Diversity and inclusion. Society of Women Engineers (SWE) and ARUP.

McIver, S. (2020, March 2). Foundation of academic woundedness from the concept of psychological woundedness [Presentation to FEMDAC U.S. cohort]. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

McIver, S. (2021, July 7). Diminishing the impact of academic woundedness [Presentation to FEMDAC International cohort]. University of KwaZulu Natal.

McLeod, P. L., Lobel, S. A., & Cox, T. H. (1996). Ethnic diversity and creativity in small groups. Small Group Research, 27(2), 248–264.

Moody, J. (2010). Rising above cognitive errors: Guidelines for search, tenure review, and other evaluation committees. Council of Colleges of Arts & Sciences. http://www.ccas.net/files/ADVANCE/Moody%20Rising%20above%20Cognitive%20Errors%20List.pdf

Moss-Racusin, C. A., et al. (2012). Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences in the United States of America , 109 (41), 16474–16479.

Muhammad, M., & López, N. (2023). Scholar while Black: Theorizing race-gender micro/macro aggressions as covert racist actions for maintaining white domination in academia a “post-racial” society. In T. Neely & M. Montañez (Eds.), Reproducing whiteness: Race and social justice in the higher education workplace. Routledge.

National Science Foundation (NSF). (2020). ADVANCE: Organizational change for gender equity in STEM academic professions. National Science Foundation. https://www.nsf.gov/funding/pgm_summ.jsp?pims_id=5383

Neal-Barnett, A. (2003). Soothe your nerves: The Black woman’s guide to understanding and overcoming anxiety, panic, and fear. Fireside Books.

Neal-Barnett, A. (2020, February 1). Understanding and Overcoming Anxiety, Panic, and Fear [Presentation]. New Mexico Black Mental Health Coalition Conference, Albuquerque, NM.

Paris, D. (2012). Culturally sustaining pedagogy: A needed change in stance, terminology, and practice. Educational researcher, 41(3), 93-97.

Player, A., Randsley de Moura, G., Leite, A. C., Abrams, D., & Tresh, F. (2019). Overlooked leadership potential: The preference for leadership potential in job candidates who are men vs. women. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 755. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00755

Quay, L. (2017). Leveraging mindset science to design educational environments that nurture people’s natural drive to learn. Association of Public & Land-Grant Universities.

Rabaka, R. (2010). Epistemic apartheid: W.E.B. Du Bois and the disciplinary decadence of sociology. Lexington Books.

Reade, J. (2015, November 3). Creating change from the middle [Presentation]. American Public Health Association Annual Meeting, Boston, MA. https://apha.confex.com/apha/143am/webprogram/Paper338142.html

Rockquemore, K. A. (2013). Mentoring series. National Center for Faculty Development & Diversity. https://www.facultydiversity.org/rethinkingmentoringcwfwc

Rothwell, J., Perry, A., & Andrews, M. (2020). The Black innovators who elevated the United States: Reassessing the golden age of invention. Brookings Institute. https://www.brookings.edu/research/the-black-innovators-who-elevated-the-united-states-reassessing-the-golden-age-of-invention/

Rucks-Ahidiana, Z. (2019, June 7). The inequities of the tenure-track system. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2019/06/07/nonwhite-faculty-face-significant-disadvantages-tenure-track-opinion

Sommers, S. R. (2006). On racial diversity and group decision making: Identifying multiple effects of racial composition on jury deliberations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(4), 597–612.

Springer, A. D. (2004a). Faculty diversity in a brave new world. Academe, 90(4), 62. http://www.aaup.org/publications/Academe/2004/04ja/04jalw.htm

Springer, A. D. (2004b). How to diversify faculty: The current legal landscape. American Association of University Professors. http://www.aaup.org/Legal/info%20outlines/legaa.htm

Stolzenberg, E. B., Eagan, M. K., Zimmerman, H. B., Berdan Lozano, J., Cesar-Davis, N. M., Aragon, M. C., & Rios-Aguilar, C. (2019). Undergraduate teaching faculty: The HERI faculty survey 2016–2017. Los Angeles: Higher Education Research Institute, UCLA.

Van Dijk, H., Meyer, B., van Engen, M., & Loyd, D. (2017). Microdynamics in diverse teams: A review and integration of the diversity and stereotyping literatures. Academy of Management Annals, 11(1), 517–557.

Vargas, J. A. (2018). Dear America: Notes of an undocumented citizen. Harper.

Vargas, J. H. C., & Jung, M. K. (2021). Introduction: Antiblackness of the social and the human. In Antiblackness (pp. 1–14). Duke University Press.

Villines, Z. (2019). How to stop ruminating thoughts. Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/326944

Whitaker, M. C., & Grollman, E. A. (2019). Counternarratives from women of color academics: Bravery, vulnerability and resistance. Routledge.

Williams, R. (2000). Faculty diversity: It’s all about experience. Community College Week, 13(1), 5.

Worthington, R. L. (2012). Advancing scholarship for the diversity imperative in higher education: An editorial. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 5, 2. National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education.

Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91.

Yuval-Davis, N. (2011). The politics of belonging: Intersectional contestations. Sage.

Zambrana, R. E. (2018). Toxic ivory towers: The consequences of work stress on underrepresented minority faculty. Rutgers University Press.

Zamudio-Suarez, F. (2021, January 26). Race on campus: The mental burden of minority professors. Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/newsletter/race-on-campus/2021-01-26

Zerai, A. (2016). Intersectionality in intentional communities: The struggle for inclusivity in multicultural U.S. protestant congregations. Rowman and Littlefield, Lexington Books.

Zerai, A. (2019). African women, ICT and neoliberal politics: The challenge of gendered digital divides to people-centered governance. Routledge.

Zerai, A., López, N., Neely, T. Y., Mechler, H., & Jenrette, M. (2021). Racial and intersectional microaggressions survey. University of New Mexico, Division for Equity and Inclusion.

Zerai, A., Perez, J., & Wang, C. (2016). A proposal for expanding endarkened transnational feminist praxis: Creating a database of women’s scholarship and activism to promote health in Zimbabwe. Qualitative Inquiry, 23(2), 107–118. doi:10.1177/1077800416660577

Zerai, A, Mupawose, A. and Moonsamy, S (in press). Decolonial methodology in social scientific studies of global public health. In Pranee Liamputtong(editor) Handbook of social sciences and global public health. Springer Nature.

Appendix A: Implicit Associations Tests

| https://implicit.harvard.edu/implicit/takeatest.html |

| Asian American (Asian – European American IAT). This IAT requires the ability to recognize white and Asian-American faces as well as images of places that are either American or foreign in origin. |

| Presidents (Presidential Popularity IAT). This IAT requires the ability to recognize photos of Donald Trump and one or more previous US presidents. |

| Weight (Fat – Thin IAT). This IAT requires the ability to distinguish faces of people who are obese and people who are thin. It often reveals an automatic preference for thin people relative to fat people. |

| Sexuality (Gay – Straight IAT). This IAT requires the ability to distinguish words and symbols representing gay and straight people. It often reveals an automatic preference for straight people relative to gay people. |

| Disability (Disabled – Abled IAT). This IAT requires the ability to recognize symbols representing abled and disabled individuals. |

| Race (Black – White IAT). This IAT requires the ability to distinguish faces of European and African origin. It indicates that most Americans have an automatic preference for white over Black. |

| Weapons (Weapons – Harmless Objects IAT). This IAT requires the ability to recognize white and Black faces, and images of weapons or harmless objects. |

| Gender – Science. This IAT often reveals a relative link between liberal arts and females and between science and males. |

| Skin-tone (Light Skin – Dark Skin IAT). This IAT requires the ability to recognize light- and dark-skinned faces. It often reveals an automatic preference for light skin relative to dark skin. |

| Religion (Religions IAT). This IAT requires some familiarity with religious terms from various world religions. |

| Gender – Career. This IAT often reveals a relative link between family and females and between career and males. |

| Arab-Muslim (Arab Muslim – Other People IAT). This IAT requires the ability to distinguish names that are likely to belong to Arab-Muslims versus people of other nationalities or religions. |

| Native American (Native – White American IAT). This IAT requires the ability to recognize white and Native American faces in either classic or modern dress, and the names of places that are either American or foreign in origin. |

| Age (Young – Old IAT). This IAT requires the ability to distinguish old from young faces. This test often indicates that Americans have an automatic preference for young over old.

Transgender (Transgender People – Cisgender People IAT). This IAT requires the ability to distinguish photos of transgender celebrity faces from photos of cisgender celebrity faces. |

Appendix B: Cumulative Professional Disadvantage

This image may help to address the ubiquitous merit issue and explain what we mean by inclusive excellence. BIPOC folks have not only risen to the top in terms of their academic accomplishments; many have also overcome cumulative professional disadvantage. What an amazing resource for our students!

Note. From “Creating change from the middle”, Joan Reede, Presentation at the American Public Health Association, 2015 https://apha.confex.com/apha/143am/webprogram/Paper338142.html

Thanks to University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign Professor Wendy Heller for this image.

Appendix C: Tool for Cultivating a Critical Reflexive Praxis Centered on Intersectionality

[1] Vargas (2018) rightly coins the term “undocumented citizen,” defined as individuals who live and work, pay taxes, and/or contribute to US talent pools, and simply do not possess citizenship documentation.