23 Advancing Institutional Mentoring Excellence (AIME): An Institutional Inclusion Initiative

Valerie Romero-Leggott; Orrin Myers; Andrew Sussman; and Rebecca Hartley

Abstract

The Advancing Institutional Mentoring Excellence (AIME) pilot project was created at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center to address concerns by faculty of color regarding feelings of isolation, lack of representation, and suboptimal retention. The purpose of AIME was to foster an institutional culture of belonging and rigorously evaluate best practices for mentoring faculty of color toward promotion and tenure. AIME used a reciprocal mentoring model, in which both mentors and mentees increased self-efficacy and skills through a structured series of exercises and encounters. Senior faculty mentors were matched with junior faculty of color mentees through an electronic mentoring platform. The curriculum featured in-person training sessions based on an adapted RESPECT model and an AIME case study, designed to improve cross-cultural communication and interpersonal skills. The signature feature of this mentoring program was an emphasis on cognitive diversity, that is, the diverse mental tools that result from different identities and cultural backgrounds, experiences, education, and training. A mixed-methods evaluation used formative measures to gather feedback from mentors and mentees about the electronic mentoring platform and curriculum. Summative measures were used for demographic profiles and preprogram, postprogram, and follow-up surveys, as well as for focus group discussions and the “most significant change” narratives. Participants reported increased job satisfaction and satisfaction with the Health Sciences Center, as well as increased institutional connectedness and knowledge of promotion and tenure processes. Further expansion and assessment of AIME is needed to confirm findings from this pilot project regarding faculty of color retention and inclusion outcomes.

Correspondence and questions about the chapter should be sent to the first author: VRomero@salud.unm.edu

Acknowledgments

The AIME pilot project emerged from the voices and stories of the faculty of color, who prevailed on the HSC leadership to be more responsive to their feelings of isolation, not belonging, and their thwarted aspirations for full participation. Gratitude goes to the faculty of color who advocated for this type of programming, to all the participants and collaborators who contributed to this project, the authorship team of the AIME final report, and to HSC Chancellor Paul Roth, Executive Vice Chancellor Richard Larson, and leadership who supported it. The report can be accessed online at https://hsc.unm.edu/programs/diversity/assets/doc/aime-executive-summary.pdf. In addition to the authors of this chapter, the AIME final report authors and key contributors included lead author Margaret Montoya, JD; Emily Haozous, PhD; Crystal Krabbenhoft; Brian Gibbs, PhD; and Nora Dominguez, PhD. Special gratitude as well to Susan Gafner, Teresa Madrid, and UNM HSC Office for DEI Executive Administrator Allie Joseph.

Mentoring Context and Program Development

The Need for This Program

The Advancing Institutional Mentoring Excellence (AIME) pilot project was created at the University of New Mexico Health Sciences Center (UNM HSC) to address concerns by faculty of color regarding feelings of isolation, lack of representation, and suboptimal retention (Montoya, et al., 2018). The AIME Final Report can be accessed online at https://hsc.unm.edu/diversity/media/files/aime-report-final.pdf.

Purpose and Objectives of the Program

The purpose of AIME was to foster an institutional culture of belonging and rigorously evaluate best practices for mentoring faculty of color toward promotion and tenure. AIME used a reciprocal mentoring model aimed at increasing mentor and mentee self-efficacy and skills through a structured series of exercises and encounters. The objective was to implement and test a cross-cultural faculty mentoring program in order to increase psychosocial support, career-related self-efficacy, job satisfaction, perceptions of institutional recognition, support, and institutional connectedness and self-efficacy while enhancing the UNM HSC’s capacity for cross-cultural communication and collaboration.

Organizational Setting and Population Served

As the only academic health center in the state, UNM HSC plays a critical role in the health and well-being of New Mexicans. The UNM HSC is a leader in providing health care and health sciences education to a diverse population. Research demonstrates that a diverse faculty enhances overall cognitive diversity leading to improved health, research, and educational outcomes (Page, 2007).

Robust mentoring programs are an important component of recruiting and retaining diverse and underrepresented minority (URM) faculty. However, URM junior faculty have less access to and limited time for mentorship compared to their nonminority peers. Additionally, they have fewer opportunities to encounter racial/ethnic concordant mentors. Furthermore, the mentors they seek out may not be adequately trained to provide appropriate mentorship (Beech et al., 2013).

In response to these concerns, the AIME pilot project sought to develop more effective faculty interactions and collaborations among mentee faculty of color and mentors by facilitating discussions about the intersectionality and psychosocial dimensions of academic life, including identity, implicit bias, career decision-making, cross-cultural communication, and other related professional development topics with an emphasis on navigating the promotion and tenure system.

Organizational Support for Mentoring Program and Infrastructure

The Faculty Workforce Diversity Committee, convened by Chancellor Paul Roth and led by Dr. Valerie Romero-Leggott and Professor Margaret Montoya, collected demographic data and information on the UNM HSC climate for faculty of color through meetings, surveys, and focus groups. Through these processes, faculty of color identified meaningful cross-cultural mentoring as an important strategy for supporting their academic development after having experienced existing HSC mentoring programs and practices as lacking.

A Diversity Engagement Survey also helped characterize the HSC climate. It was administered in 2012 to measure and describe the inclusiveness of the academic environment. The survey drew upon workforce engagement theory and components of organizational inclusion. The items in the survey were mapped to the following eight inclusion factors: trust, appreciation of individual attributes, sense of belonging, access to opportunity, equitable reward and recognition, cultural competence, respect, and common purpose (Person et al., 2015).

The AIME pilot project was the culmination of collaborative work over several years. Many stakeholders, including deans, chairs, faculty, administrators, and staff, from the HSC as well as colleagues from UNM’s main campus, comprised the AIME Planning Committee and/or were instrumental in the Faculty Workforce Diversity Committee work that led to the pilot project.

Operational Definition

Mentoring was operationally defined for this program as guiding academic and professional growth in an identity-conscious manner.

Theoretical Framework

A thorough review of the literature and research synthesis conducted for the mentorship pilot confirmed that, notwithstanding progress in establishing successful/best practices in faculty mentoring, very little evidence-based research addressed the specific topic of mentoring faculty of color in academic health centers. The study used culturally appropriate evaluation methods, including narrative methods, focus groups, and reliance on culturally responsive research, implementation, and evaluation criteria. Evaluation included the psychosocial dimensions of academic life such as unconscious bias, identity formation, faculty agency, respect, isolation, and cross-cultural communication. By focusing on the psychosocial and cultural contexts involved, the intention was to create an active, personalized, and team-based mentorship program that aimed to acknowledge and/or further develop the full potential and untapped human capital of faculty of color and thereby improve career-related self-efficacy and satisfaction.

A signature feature and theory that informed this mentorship program is cognitive diversity (Horwitz & Horwitz, 2007). Cognitive diversity refers to differences between team members in characteristics such as expertise, experiences, and perspectives. These differences can also include sociodemographic characteristics including race, ethnicity, and sex. The cognitive diversity hypothesis posits that diversely composed groups may generate a broader range of ideas in order to solve problems creatively. While research findings are variable, there is evidence that cognitive diversity is positively related to benefits in group performance outcomes (Horwitz & Horwitz, 2007). In short, cognitive diversity is the diverse mental tools that result from different identities and cultural backgrounds, experiences, education, and training, which collectively are proven contributors to better problem-solving skills (Page, 2007). A culturally responsive conceptual framework was also vital to the development of this program (Han & Onchwari, 2018). A culturally responsive mentoring program incorporates the cultural orientations and experiences of participants to enrich each of them (Bennet, 1988; Hofstede, 2011; Hofstede & McCrae, 2004; Rosinski, 2003).

Typology of Program

Hierarchical mentoring, where a more senior mentor is matched to a junior mentee (Kram, 1988), was combined with group mentoring (see Chapter 3 for diverse mentoring relationships) (Friedman et al., 1998), with the intention that each mentee would be matched with up to three more senior mentors. This could also be considered a mentoring panel, many-to-one, or committee model since a panel of mentors worked with each mentee. Due to time constraints and availability of mentors, two mentors and one mentee composed most teams. This triad worked together as a team with the mentors and mentee meeting quarterly; however, the mentee decided if they preferred a lead mentor whereby this could lead to an occasional one-on-one meeting.

Mentoring Inputs and Resources

Curriculum Description

The participants’ estimated time commitment for the year was less than 60 hours. Activities were based on an adapted RESPECT model (Mostow et al., 2010), cognitive diversity scholarship (Horwitz & Horwitz, 2007; Page, 2007; Page & Nivet, 2015), and a case study. The RESPECT model is an action-oriented set of communication and relational behaviors designed to build trust across differences in race/ethnicity, culture, and power. Its component skills and educational framework are:

- Respect

- Explanatory model

- Social context, including stressors, supports, strengths, and spirituality

- Power

- Empathy

- Concerns

- Trust/Therapeutic alliance/Team

The emphasis on cognitive diversity was based on research evidencing that teams of individuals with a range of perspectives and experiences outperform groups of like-minded experts (Page & Nivet, 2015). Four cross-cutting themes drawing on RESPECT and cognitive diversity organized the curriculum:

- cross-cultural communication,

- racial/ethnic identities and cognitive diversity,

- implicit bias, and

- faculty agency in promotion and tenure.

Each theme was integrated into the curriculum through an evolving case study that highlighted a cross-cultural relationship between a Native American junior faculty (mentee) and her non-Hispanic, white male department chair.

Funding

The AIME program was jointly funded by the UNM HSC Chancellor’s Office and the HSC Office of the Vice-Chancellor for Diversity and Inclusion (HSC D & I). The chancellor committed to funding this program as it was institutionalized.

Mentoring Activities

Recruitment Activities

Participants were recruited via email with the assistance of UNM HSC deans, vice-chancellors, and department chairs. Junior faculty of color were recruited as mentees, while more senior faculty of color and non-faculty of color were recruited as mentors.

Matching Activities

Faculty mentors were matched with faculty of color mentees through an electronic mentoring platform, Insala (https://www.insala.com/mentoring), originally created to facilitate business mentoring relationships.

This mentoring platform was adapted for academic users by a collaboration with Insala. The AIME participants found that Insala was effective for uploading biographies and CVs, viewing mentor and mentee profiles, and indicating mentor and mentee preferences. After the initial mentor-mentee matching had occurred, participants did not find Insala effective as a communication medium, given that they were already using other types of software for email and texting.

If mentoring programs with larger mentor-mentee cohorts are contemplated, an electronic tool with Insala’s capabilities might be useful to optimize information sharing. This matching process depends on multiple documents being shared among the participants in a fairly short period of time.

Training Activities

Mentees and mentors attended a 6-hour orientation that began with a cultural simulation activity entitled BaFa’ BaFa’ Learning Simulation (BaFa’ BaFa’ Learning Simulation, n.d.), designed to foster cross-cultural awareness of the development and impact of stereotypes. They also received information on the overall program, the other cross-cutting themes, the basics of mentoring, and the use of Insala.

Mentees were asked to meet for an hour at least once a month with their selected mentor(s). During the first meeting, mentees developed an Individual Learning Plan for the year and posted it on the Insala platform. The learning plan established professional and personal, short- and long-term goals. It also identified areas of focus, resources, potential barriers, required time commitment, personal strengths, areas for improvement, and an action plan. During subsequent meetings, mentees reviewed their progress toward goals and posted a summary directly onto Insala.

Mentors and mentees also attended four 1-hour case-based training (lunch) sessions over a 6-month period to assess mentoring progress and best practices and examine and explore cross-cultural communication. The curriculum used an iterative and cumulative pedagogical approach, introducing all cross-cutting themes at orientation, then exploring each theme in greater depth in the shorter training sessions. At each training session, a cross-cutting theme was reintroduced and integrated into the cross-cultural mentoring case study. Each session built on the previous sessions while incorporating the new content, cross-referencing the earlier themes, and building context throughout the process, as well as taking into account the feedback from evaluation surveys. The discussions allowed the participants to work together in diverse teams and to reflect on the mechanics of cognitive diversity. The importance of personal storytelling as a method for strengthening relationships between faculty of color and their department chairs, peers, and mentors was reinforced by the use of the “most significant change” narratives as a qualitative evaluation technique (Dart & Davies, 2003; Rivera, 2012).

Formative and Summative Evaluation

The study used culturally appropriate evaluation methods, including narrative methods, focus groups, and reliance on culturally responsive research, implementation, and evaluation criteria. Evaluation included the psychosocial dimensions of academic life such as unconscious bias, identity formation, faculty agency, respect, isolation, and cross-cultural communication.

Mentees and mentors completed program surveys relating to demographics, institutional diversity, cognitive diversity, faculty agency, and programmatic goals and objectives.

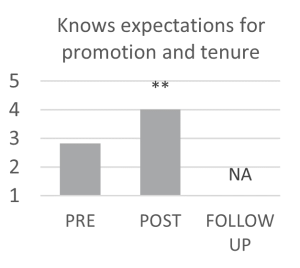

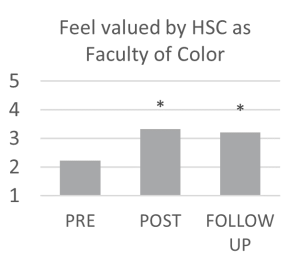

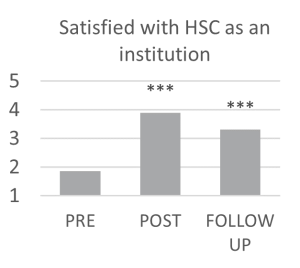

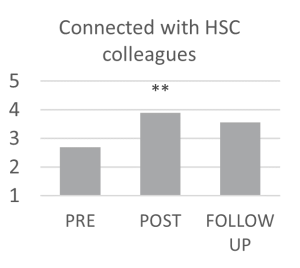

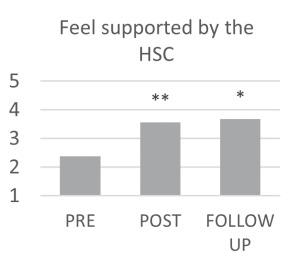

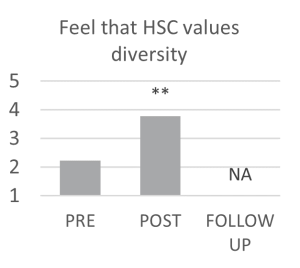

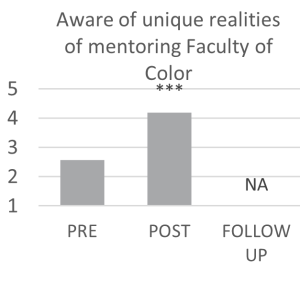

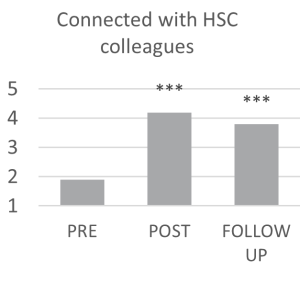

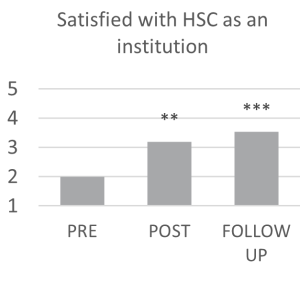

Mentees showed significant improvement in knowledge of expectations for promotion and tenure, feeling valued by HSC as faculty of color, satisfaction with HSC as an institution, connection with HSC colleagues, feeling supported by the HSC, and feeling that HSC values diversity (Figure 23.1). Mentors perceived improvements in their awareness of the unique realities of mentoring faculty of color, their connection with HSC colleagues, and their satisfaction with HSC as an institution (Figure 23.2). Importantly, the results also suggest maintenance of these gains at a 12-month follow-up for both mentees (feeling valued, supported, and satisfied) and mentors (connection and satisfaction).

These results align closely with a review concluding that health professions schools can improve faculty of color retention through focused efforts to improve the institutional culture to promote an inclusive environment (Hamilton & Haozous, 2017). They also support studies that conclude that, in general, faculty who receive mentoring experience greater job satisfaction than those who do not (Zambrano et al., 2015).

| Figure 23.1

Mentee Survey Responses: Improvements in Pre- and Post-Program Ratings |

||

|

||

| 1 Strongly disagree, 2 Disagree, 3 Neutral, 4 Agree, 5 Strongly agree | ||

| Evaluated using non-parametric Wilcoxon tests. * P<0.05 ** P<0.01 *** P<0.001 |

| Figure 23.2

Mentor Survey Responses: Improvement in Pre- and Post-Program Ratings |

||

|

||

| 1 Strongly disagree, 2 Disagree, 3 Neutral, 4 Agree, 5 Strongly agree | ||

| Evaluated using non-parametric Wilcoxon tests. * P<0.05 ** P<0.01 *** P<0.001 |

Mentoring Outputs

All mentees were URM (n = 14) compared to 46% of mentors (11 of 24). Both mentees (71%) and mentors (67%) were predominantly female. The majority of mentees (86%) and mentors (92%) were based in the School of Medicine, while the remaining participants were from the College of Nursing.

Mentoring Outcomes and Lessons Learned

Outcomes of Program

The UNM HSC AIME pilot project created an opportunity and setting for faculty of color to build relationships with like-minded colleagues, discuss their career choices in the context of individual, family, and institutional demands, and examine academic choices made by their peers. The summative assessment findings revealed significant improvements in mentees feeling valued, connected to colleagues, and supported by and satisfied with their HSC institution. Thus, AIME was successful as a pilot in addressing the project goal and advancing inclusion but probably did not improve the overall institutional climate. We expect, with increased faculty retention and further AIME-modeled mentoring programs, to see these broader impacts over time.

Sustaining the Program

AIME is a partial solution to fostering an inclusive climate by promoting a fuller understanding of the contributions of faculty of color through robust discussions with faculty from different backgrounds about the complex dimensions of academic healthcare careers in New Mexico.

Elements from AIME have been applied to inform and improve an existing HSC Faculty Mentorship Development Program based in the UNM SOM Office of Faculty Affairs and Career Development. AIME is also part of the 2021 State of Mentoring review at UNM HSC. The chancellor intended to provide funds to the HSC D & I to institutionalize the program. Should this program be initiated in the future, HSC D & I would request funding from the HSC Executive Vice President’s Office.

Lessons Learned

While the findings from this pilot were encouraging, there are some important limitations. The overall sample size for the AIME pilot project was relatively small, which limits replicability and generalizability. The pilot did not include a comparison group, and there was attrition across measurement periods. Therefore, nonresponders might have had different responses as compared to responders. We also did not track responses by unique identifiers, so pre- and post-program changes are reported in the aggregate, and we were unable to track based on attrition. Some mentees had low satisfaction scores that might have implications for long-term retention; however, individual participants were not identified as part of this study.

The qualitative evaluation was structured in an opportunistic manner, seeking to triangulate among different sources of information to inform our understanding of the program. We were unable to complete the projected number of focus groups due to program participants’ competing demands. The findings from this component may not reflect the full spectrum of experiences and perspectives. It is important to note, however, that our quantitative data analyses demonstrated consistent increases in virtually all areas of assessment. Additionally, the qualitative data were highly complementary to these findings, providing further confidence in the outcomes reported here. Future interventions should track participant evaluations by unique identifiers for the purpose of measurement.

Recommendations for Future Designers and Stakeholders of Academic Mentoring Programs

These recommendations are directed specifically toward academic mentoring programs to support faculty of color and to cultivate the wide range of talent and abilities represented by a diverse faculty:

- Identify and develop best practices for faculty of color recruitment, hiring, promotion, and retention specific to your institution.

- Implement AIME-type mentoring programs for all faculty and academic administrators in collaboration with existing mentorship programs.

- Ensure rigorous evaluation and assessment of the programs.

- Implement faculty of color academic leadership development initiatives to expand the pool of faculty of color mentors for the future.

- Increase transparency related to diversity by disseminating an annual report of the demographic profile of faculty and leadership.

References

BaFa’ BaFa’ Learning Simulation. (n.d.). BaFa’ BaFa’ – cross culture/diversity for business. Simulation Training Systems. Retrieved February 2022 from https://www.simulationtrainingsystems.com/corporate/products/bafa-bafa/

Beech, B. M., Calles-Escandon, J., Hairston, K. G., Langdon, S. E., Latham-Sadler. B. A., & Bell, R. A. (2013). Mentoring programs for underrepresented minority faculty in academic medical centers: A systematic review of the literature. Academic Medicine, 88(4), 541–549. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828589e3

Bennett, J. M. (1988). Cultivating intercultural competence: A process perspective. In The SAGE handbook of intercultural competence (pp. 121–140). SAGE Publications, Inc.

Dart, J., & Davies, R. (2003). A dialogical, story-based evaluation tool: The most significant change technique. American Journal of Evaluation, 24(2), 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1177/109821400302400202

Friedman, R., Kane, M., & Cornfield, D. B. (1998). Social support and career optimism: Examining the effectiveness of network groups among black managers. Human Relations, 51(9), 1155–1177.

Hamilton, N., & Haozous, E. A. (2017). Retention of faculty of color in academic nursing. Nursing Outlook, 65(2), 212–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.outlook.2016.11.003

Han, I., & Onchwari, A. J. (2018). Development and implementation of a culturally responsive mentoring program for faculty and staff of color. Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies, 5(2), Article 3. https://doi.org/10.24926/ijps.v5i2.1006

Hofstede, G. (2011). Dimensionalizing cultures: The Hofstede model in context. Online Readings in Psychology and Culture, 2(1). https://doi.org/10.9707/2307-0919.1014

Hofstede, G., & McCrae, R. R. (2004). Culture and personality revisited: Linking traits and dimensions of culture. Cross-Cultural Research, 38(1), 52–88.

Horwitz, S. K., & Horwitz, I. B. (2007). The effects of team diversity on team outcomes: A meta-analytic review of team demography. Journal of Management, 33(6), 987–1015. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307308587

Kram, K. E. (1988). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. University Press of America.

Montoya, M., Hartley, R., Myers, O., Sussman, A., Haozous, E. and Krabbenhoft, C., Romero-Leggott, V., 2018. AIME: Advancing Institutional Mentoring Excellence. [online] Available at: https://hsc.unm.edu/diversity/_media/_files/aime-report-final.pdf

Mostow, C., Crosson, J., Gordon, S., Chapman, S., Gonzalez, P., Hardt, E., Delgado, L., & David, M. (2010). Treating and precepting with RESPECT: A relational model addressing race, ethnicity, and culture in medical training. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 25(Suppl. 2), S146–S154.

Page, S. E. (2007). The difference: How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools, and societies. Princeton University Press.

Page, S. E., & Nivet, M.A. (2015). The difference: How the power of diversity creates better groups, firms, schools, and societies [Video]. Association of American Medical Colleges. https://www.aamc.org/initiatives/diversity/learningseries/313852/page-webinar.html

Person, S. D., Jordan, C. G., Allison, J. J., Ogawa, L. M. F., Castillo-Page, L., Conrad, S., Nivet, M. A., & Plummer, D. L. (2015). Measuring diversity and inclusion in academic medicine: The diversity engagement survey. Journal of Academic Medicine, 90(12), 1675–1683. https://www.aamc.org/media/20916/download?attachment

Rivera, M. (2012). Story-based evaluation methods and the most significant change (MSC) technique: Responsive evaluation options for the pilot mentoring program for faculty of color [Unpublished]. University of New Mexico.

Rosinski, P. (2003). Coaching across cultures: New tools for leveraging national, corporate & professional differences. N. Brealey.

Zambrana, R. E., Ray, R., Espino, M. M., Castro, C., Cohen, B. D., & Eliason, J. (2015). “Don’t leave us behind”: The importance of mentoring for underrepresented minority faculty. American Educational Research Journal, 52(1), 40–72.