1 Mentoring Origins and Evolution

Bob Garvey

Abstract

This chapter is in nine parts. The first explores the origins and meanings of mentoring from the Ancient Greek to modern times in different parts of the world. The second section discusses the similarities and differences between mentoring and other developmental relationships.

The third part explores the difficulties in defining mentoring. As an alternative to a definition, the fourth part looks at the dimensions of mentoring and the fifth part explores how the dimensions could be applied in practice. Following this, the sixth section considers a range of mentoring arrangements found in academia and uses the dimensions framework to develop descriptions of mentoring in different contexts in higher education. The seventh considers some practical developments of mentoring in higher education. The eighth section briefly considers the mentoring research agenda in academia.

The final section brings these ideas together and concludes that mentoring offers great potential for growth and development in many different contexts.

No conflicts of interest to disclose.

Correspondence concerning this chapter: bob@coachmentoring.co.uk

Acknowledgements

In memory of Margaret, my inspiration.

The Origins and Meanings of Mentoring

The Ancient Greeks

You may be wondering why it is necessary to understand the history of mentoring. First, history gives us a baseline. If we know where something has come from, we understand how it has evolved and developed over time but also how these early ideas influence the present and possibly the future as well. Understanding the history of mentoring also shows us how it has been created as a social activity. Finally, history is often about versions of a story. In the mentoring world, there are many stories; some are used to present an impression of what mentoring actually is. Let’s examine the origins and think about what impression an author is trying to create by linking modern mentoring to history.

To begin at the beginning, the word “mentor” comes from Homer’s epic poem “The Odyssey.” The prefix “men-” is translated from ancient Greek and means “of the mind” or “one who thinks,” and “-tor” is the suffix meaning “man.” In the feminine form, the suffix would be “-trix.” So, mentor literally means “a man who thinks” and mentrix is “a woman who thinks.”

The original story of Mentor, found in Homer’s “The Odyssey,” appears in the section about King Odysseus’s son, Telemachus. Telemachus in Ancient Greek means “far from the battle.” Telemachus is therefore positioned in the story as weak and in need of protection. The poem is set on the island of Ithaca. Odysseus leaves the protection of his son to his trusted friend, Mentor. Unfortunately, Mentor is not up to the task, and the kingdom becomes unstable due to the arrival of many unsuitable suitors who think the king is dead and wish to marry Queen Penelope. Athene, “the goddess of civil administration, war and, most notably, wisdom” (Harquail & Blake 1993, p. 3), is sent by Zeus to protect the stability and wealth of Ithaca during Odysseus’s absence, and she sees Telemachus as key to the achievement of this aim. She appears in the form of Mentor and sets about the task of educating Telemachus in the ways of kingship of the times. Athene sets the young man some challenges. One of these challenges is to take a voyage to find out if his father is dead. During these adventures, Telemachus learns to be a fierce warrior. At the end of the story, Odysseus returns, and Telemachus joins his father to rid the court of the suitors and there follows a very bloody and violent battle in which Odysseus and Telemachus are victorious, as this quotation illustrates:

So he spoke, and taking the cable of a dark-prowed ship, fastened it to the tall pillar, and fetched it about the round-house; and like thrushes, who spread their wings, or pigeons, who have flown into a snare set up for them in a thicket, trying to find a resting place, and meeting death where they had only looked for sleep; so their heads were all in line, and each had her neck caught fast in a noose. So that their death would be most pitiful. They struggled with their feet for a little, not for very long.

They took Melanthios along the porch and the courtyard. They cut off, with pitiless bronze, his nose and his ears, tore off his private parts and gave them to the dogs to feed on raw, and lopped off his hands and feet, in fury of anger. (Lattimore, 1965, vs. 461–475)

This quotation from “The Odyssey” is part of the climax of the story, in which Odysseus returns and joins Telemachus to rid Ithaca of the suitors and those who colluded with them while Odysseus was away fighting the Trojan wars. To modern ears, this sounds bloodthirsty, merciless, and vengeful. The men who preyed on Penelope and their female collaborators are dispatched and defiled with an element of viciousness and glee.

So, how is it that such violence could be part of our prototype for adult development?

Despite many modern writers (Lean, 1983; Clutterbuck, 1992; Garvey, 1994b Eby et al., 2007; Starr, 2014; Rolfe, 2021), myself included, suggesting that Ancient Greece is the origin of mentoring, the word “mentor” does indeed come from these times but the meaning of mentoring activity as we understand it now clearly does not!

These links form what Garvey (2017, p. 15) calls the “old-as-the-hills” argument. This argument somehow confers substance to the mentoring concept because it is old and has stood the test of time.

Medieval Times

You have probably read or heard that some people (for example, Gay and Stephenson, 1998; Purkiss, 2007; Rolfe, 2021) make links to medieval times by comparing mentoring to the relationship between knight and squire and the craftsperson-and-apprentice model.

What do you think about linking mentoring to the medieval period? On what historical basis do they do this? Let’s look at these claims in more detail.

Like the Ancient Greek old-as-the-hills argument, the link to medieval times is also a misunderstood and possibly romanticised notion of the mentoring story.

Medieval times were very different from today. Contemporary accounts suggest that the knight and squire relationship was not based on honor and chivalry as Hollywood would like us to believe! Instead, the relationship was based on feudalism, injustice, disease, and poverty. Essentially, the knight was a mercenary who basically ran protection rackets (Jones, 2015) and the squire was conditioned into this role and exploited along the way. Garvey (2017) argues that this is “a male-dominated narrative of paternalistic care with the agenda being with the mentor or the holder of power” (p. 20).

Is this how we would wish mentoring to be understood now?

The apprenticeship model was no different from the knight-and-squire model. In this period, apprenticeships for poor children were compulsory and legally enforceable. Despite risking imprisonment, it is recorded that 50% of apprentices failed to complete the indenture (Jones, 2015). Parents paid fees to the master, and children were exploited as a form of cheap labor.

Is this how you would like your mentoring program to be?

Probably not! Like the knight-and-squire model, the apprenticeship model is also flawed; curiously, writers make the association with present-day mentoring uncritically. This point is discussed later in this chapter.

Both of these links to mentoring are based on romanticized notions of history, perhaps given to us by the film industry!

18th and 19th Century

Having discounted the Ancient Greeks and the medieval period, we come to the 18th and 19th centuries; this offers us something more relevant. Roberts (2000) states that the word “mentor” was not present in the English language until 1750 and that any earlier associations are false. However, it is in early 18th-century France when the first account of mentoring in the form we may recognize it today appears.

Educational content of that time was based on Ancient Greek and Roman mythologies, and this probably explains how the story of Mentor entered people’s consciousness in that period of history.

The cleric and educator, Fénelon (1808) published the book Les Aventures de Telemaque as an educational treatise in France in 1699. Fénelon’s work was translated into English and was first published in England in 1760. Lee (2010) argues that Fénelon’s work presents the version of mentoring we are familiar with in modern times, and the word is currently used with reference to Fénelon’s character Mentor. Riley (1994) argues that Fénelon’s philosophy of love, without the “fear of punishment” or the “hope of reward,” is applied to his character, Mentor. Here we have Mentor described as a generous and altruistic character.

When Fénelon’s book was published, it was viewed as controversial. Although it was based on “The Odyssey,” insofar as the characters are the same, the book, written as a poem, is an account of the growth and development of Telemachus with the help, support, and guidance of a generous and kind Mentor.

Fénelon was of the Enlightenment period in history, and his book deeply influenced educational philosophy, with its roots firmly in the humanist school of learning. It was aimed at spreading morality and enlightened ideas to the widest possible audience, including women and children. Fénelon’s Mentor is presented as the hero who made speeches and offered advice on how to lead. Mentor denounces war, indulgence, and selfishness. He argues for altruism and recommends the overhaul of the government, the abolition of the feudalistic mercantile system, and cruel peasant taxes and advocates a parliamentary government and a federation of nations to settle disputes between nations peacefully—an enlightened text indeed!

For his trouble, Fénelon was banished to Belgium and had his pension cancelled by the King. Despite this, Les Aventures de Telemaque was translated into several European languages and became a bestselling book. Fénelon’s work influenced others in Europe as the mentoring story spread through publications. For example, Lord Chesterfield’s (1737–1768) Letters to his Son, first published in 1774, urges his son to trust and take notice of his wise mentor. The book The True Mentor; Or, the Education of Young Men in Fashion by Caraccioli and published in English in 1760, describes how to be a mentor based on Fénelon’s work. The educational philosopher Rousseau published the book Emile in France in 1762. Again, this is based on Fénelon’s work. Rousseau also said that the ideal class size for education was a one-to-one ratio of student to teacher! Murry published Mentoria: The Young Ladies Instructor in London in 1778, a collection of lessons for young women. Honoria published three volumes of The Female Mentor in 1793 and 1796, using Fénelon’s work as its basis. These works were probably the first descriptions of group mentoring (see Group Mentoring in this chapter and in Chapter 3). The poet Lord Byron refers to Mentor in three of his poems, “The Curse of Minerva” (1821); “Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage” (1829); and “The Island” (1843).

Roberts (1998) argues that Fénelon’s Mentor is androgynous and therefore has the qualities of both male and female.

Fénelon’s Mentor demonstrates the ability to proffer calm advice, admonish with reason, nurture, and guide, empathise, display aggression in the protection of his charge and consideration of ending the mentoring relationship. . . . Both stereotypically masculine and stereotypically feminine personality traits seem apparent in Mentor’s behaviour towards his charge; after all, Fenelon’s Mentor was half-male and half-female. (p. 19)

In brief, Fénelon’s Mentor offers us a model of Mentor that is still relevant today and includes such qualities as fostering independence and self-efficacy by supporting and challenging the learner. He bases his educational ideas on what we now might call experiential learning. There is a strong ethical base to Fénelon’s Mentor, and it is clear that Fénelon understood mentoring as providing what we might now call psychosocial support and development. Trust was at the heart of Fénelon’s Mentor, as was an altruistic intent.

This seems more like the mentors we would like to have in our programs!

According to Irby and Boswell (2016), the term “mentoring” first appeared in America around 1778. They claim that the book published in 1778 by Ann Murry called Mentoria: The Young Ladies Instructor was the first time the word “mentor” was used in print in the United States. However, it is curious that Ann Murry’s book was published in London, where she was a private tutor to the Princess Royal, Amelia. The introduction of the book is a dedication to Princess Amelia. The book is written, similarly to Honoria’s The Female Mentor, in the style of a mentoring conversation and was primarily aimed at the education of young ladies. The book was very popular, and by 1823 it had been published in twelve editions. Perhaps the book was exported to America, but, more likely, the first publication in America that used the term “mentor” was a book called The Immortal Mentor: Or, Man’s Unerring Guide to a Healthy, Wealthy, and Happy Life. In Three Parts. This instructional text was written by Lewis Cornaro, Dr. Franklin, and Dr. Scott and published by Francis and Robert Bailey for the Reverend Mason L. Weems in 1796.

Some cultures are suspicious of mentoring. A 19th-century development offers an explanation as to why. In 1894, George du Maurier published the novel Trilby, in which he creates an evil character called Svengali. Svengali is an evil hypnotist with sinister intent who manipulates people to serve his own ends. The novel was a massive success, and in the early days of filmmaking, Svengali was a dominant character in many silent films and later in talking pictures. The character’s name has also been associated with mentoring, which perhaps represents the darker side of mentoring, in which the mentor is a controlling figure giving advice.

Not the mentor we would like in our programs!

Modern Developments of the Mentoring Model

William David Moffat created The Mentor Association in America in 1912. This was like a think tank group that gathered together men from different specialisms to share their knowledge. This was disseminated through the publication of The Mentor, first published in 1913. The first volume stated in its introduction:

The object of The Mentor Association is to enable people to acquire useful knowledge without effort, so that they may come easily and agreeably to know the world’s great men and women, the great achievements, and the permanently interesting things in art, literature, science, history, nature and travel. (Mabie, 1913, p. 1)

Mentoring in this association clearly had an educative function. In the early days, it was not particularly successful as a publication; however, by 1930, it had achieved a circulation of 85,000. But by 1931, it had stopped publication.

The now well-known Big Brothers Big Sisters of America had their origins in the early 1900s. Big Brothers was started by Ernest Coulter, a journalist, lawyer, and public administrator, because he was concerned about the high numbers of boys that were coming through his courtroom in New York. He noted that caring adults could help to keep these boys out of the legal system, and he set about finding volunteers to offer mentoring to the boys. Around the same time, a group called the Ladies of Charity was established to befriend girls who came through the court system. Both voluntary groups worked independently from each other until 1977, when they joined together to form Big Brothers Big Sisters of America.

In the research world in 1978, Levinson et al. presented a modern concept of mentoring in the book The Seasons of a Man’s Life. This book presents a substantial model of male development in which mentoring plays a key role. Levinson et al. (1978) use the term “mentor” for someone, often half a generation older, who helps accelerate the development of another in his age-related transitions, which they refer to as “mentoring the dream.” The research found that mentoring, when applied to age transitions, could reduce the transition from an average of seven years to three years for those with mentors. Arguably, it was this research that started the movement toward mentoring for career acceleration, and when Collins and Scott published their article “Everyone Who Makes it Has a Mentor” in the Harvard Business Review of 1978, mentoring was expanding in the USA!

In the book Passages: Predictable Crises of Adult Life (1976), Gail Sheehy discussed adult development mainly from the female perspective. She noted that mentoring relationships were not so common among women; however, some 20 years later, in her revised edition, New Passages: Mapping Your Life Across Time (1996), she adds developmental maps on males and notes that mentoring had become common for women and men alike due to many societal changes since her first book.

In the United Kingdom, Clutterbuck (1985) published a book called Everyone Needs a Mentor. This was probably the first publication to look at mentoring in business settings in the United Kingdom, and in 1988, David Megginson published a paper entitled “Instructor, Coach, Mentor: Three Ways of Helping for Managers,” and these two publications, taken together, seemed to signal the start of mentoring in business contexts in the United Kingdom a few years behind the United States!

Mentoring in the education sector seemed to start in the early 1990s in the United Kingdom and has been represented through the journal Mentoring and Tutoring since 1993. In the United States, publications on mentoring in the education sector were appearing around the same time. Also, during the 1990s in the United Kingdom, the government was investing heavily in mentoring for young people aimed at employment policies and prevention of criminality and drug abuse.

Since these beginnings in in the 1980s and ’90s, mentoring activity has spread to many parts of the world where it is employed for various purposes in various contexts. For example, Youth Business International offers volunteer mentoring to support and develop youth entrepreneurship in 52 countries around the world, supporting 169,000 young people in being economically active. Other large international charities such as MSF (Doctors Without Borders), World Wildlife Fund, Greenpeace, and Save the Children have extensive international mentoring programs for staff, and mentoring is found for students, staff, and faculty in the higher education sector in America, Australia, Canada, New Zealand, South Africa, and the United Kingdom (Lunsford et al. 2017).

Further Developments of the Mentoring Model

Mentoring, being a social process, has changed and adapted since its earlier conceptualizations as an essentially one-to-one model. As a social construction, created by people to serve particular contextual purposes, there are now many varied mentoring forms in use around the world. There may be variations in the types of mentees, for example:

- a peer

- a team member or group of mentees

- someone who is younger or older than the mentor

- someone with different experience

- someone who is known to the mentor or someone they have not met before

- someone from a different department, function, or subject discipline

- someone from a different organization

What is common to all cases of mentoring is that the mentee comes to view things in a new way. The mentor promotes change in the mentee, helping that person or persons toward a new vision of what is possible.

Who will be the mentors and who will be the mentees in your mentoring program? Giving thought to that is important because you want to get the right people involved!

Mentoring may have different purposes. For example, mentoring may be used to help with induction, onboarding, or helping students understand college life and its expectations. Mentoring can be used for developing leadership abilities in many different situations, such as at school, at work, and in other social settings. In the workplace, it may assist in succession planning or talent programs and developing potential managers of the future to develop potential and capabilities.

Mentoring could be used to simply help people think about the things that are important to them at whatever age they are. It can also be used to help progress people’s careers by supporting learning and development. Another important use of mentoring is to develop respect and to understand and to value cultural diversity. Mentoring can be used to support people in change and transition (see Alred & Garvey, 2019).

What are you going to use mentoring for? Being clear about the purpose of mentoring is very important. If you don’t have a clear purpose, it can lead to confusion among those trying to work with it!

Mentoring can also take on different forms and these relate to your purpose and the people you are hoping to take part in the program.

Developmental Mentoring and Developmental Networks

Where the mentor supports the mentee’s learning and development is often part of your mentoring structure and can show up within the private, public, or social sectors. It may also include having a mentoring program as a developmental network of people who may provide a range of different kinds of developmental support. Here, a mentee has access to a pool of mentors who may offer different types of mentoring. No person is an island! We all exist within a network of different relationships. This idea, in relation to mentoring, is about individuals who may draw on a number of different mentoring-type relationships in a variety of ways. It may be, for example, to get different views on an issue or it may be to simply run an idea past several people. A mentor may give their mentees access to their networks. To extend this idea further, we could arrive at the notion of a mentoring organization, where there are many mentors willing and able to support others in their learning and development (see Alred & Garvey, 2000; Garvey & Alred, 2001; and Chapter 3 of this volume).

In 2001, Higgins and Kram identified developmental networks in some organizational settings. In essence they suggested that developmentally aware people often had more than one developer, or mentor, and it is possible that an individual will be part of a network of developers who contribute to that individual’s learning and development. Some people would make regular use of their developmental network and others would make less use of it.

When you think about your program, what is your view on the developmental network? Are you expecting your mentees to only have one mentor, or would you identify a group of people who could fulfill this role and would be willing to offer their time to help support learning and development? What might be the practical challenges of this? How might the following mentoring forms be helpful or not in your program?

Hierarchical Mentoring

Some (see Chapter 3) suggest that this is the traditional mentoring form. It is about fast-tracking the mentee in their career. This may be linked to talent-management programs in organizational settings, but it may also be found in educational settings where talent might be supported and nurtured by a mentor.

Peer Mentoring

This can take various forms. Essentially, it happens between individuals who may have similar experience, status, or power. In some contexts, this can be referred to as a “thinking partner” arrangement. These relationships are often mutually beneficial, particularly as the potential power dynamics between the dyad are largely eliminated, and this facilitates good, open conversation.

Reverse Mentoring

Here the mentor is younger or more junior than the mentee. It focuses on the differences of experience, understanding, and attitudes as mentor and mentee learn about each other’s worlds (Alred & Garvey, 2019, p. 31).

Reciprocal Mentoring

This is where both parties to the relationship work with each other to learn and grow for mutual benefit.

Group Mentoring

Interestingly, this was the type of mentoring described in Murry’s and Honoria’s publications from the 18th century (mentioned earlier in this chapter). Group mentoring maybe be found in educational settings and, in the United Kingdom at least, in public sector organizations. It is where a mentor may facilitate the learning in a group or, in some cases, it is self-facilitated by group members. This may take the form of action learning sets (see Revans [1983] and Chapter 3 of this volume).

Differentiating Mentoring from Other Developmental Relationships

Do you find that people often ask, what’s the difference between coaching and mentoring? What’s the difference between an academic advisor and a mentor? Isn’t mentoring a bit like counseling? Isn’t supervision, tutoring, or pastoral care like mentoring? The answer to these questions is that it all depends on the purpose, context, and intention!

Garvey (2004) suggests that there are three main “helping” activities: counseling, mentoring, and coaching. Counseling is a skilled activity that focuses on the individual’s needs and assumes that there is some kind of pathology present. There are many different forms of counseling, but often it is about exploring the past in order to find a new way of behaving or thinking. The counselor attempts to offer a neutral position to the client but is an expert in the psychological state of the client.

Mentoring is also a skilled activity that essentially focuses on the holistic development of the mentee. A mentor has been described as the highest-level educator. The mentor may use their experience and engage in a learning relationship with the mentee. A mentor tends to be actively engaged in the relationship.

Coaching is also a skilled activity and tends to focus on the coachee’s performance. The coach is often neutral in relation to the client and will be expert in coaching and not the coachee’s context or issues.

However, the borders and boundaries are not always clear, and in the case of mentoring and coaching, there is a view that the skills of the coach can be appropriate for the mentor and that the use of the coach’s experience can also be helpful to the coachee. Stelter (2019) argues for what he calls the third generation of coaching. Here he suggests that a coach or a mentor are both “facilitators of dialogue,” and Garvey and Stokes (2022) argue that there is a hybridization of coaching and mentoring beginning to emerge across different sectors.

Supervision in the context of education could be a form of mentoring or coaching. However, much depends on how it is done. If its focus is on a nondirective facilitation of the learner’s performance, it could be coaching. If it is focussed on the holistic learning and development—often in a nondirective way—on the learner, it could be a form of mentoring. However, in academia, sometimes this may go wrong, and ethical issues start to appear.

If the supervisor is using the learner as “cheap labor,” as it was in medieval times with the craftsperson and apprentice model raised earlier in this chapter, it is ethically dubious. If the supervisor is using the learner to write a paper for publication without proper acknowledgement of the learner’s contribution, this is also exploitation of the medieval kind! If the supervisor is using the learner to complete their own research without due acknowledgement, this is also ethically wrong.

Advice-giving is also potentially problematic. It is also a common issue in educational settings where the educator is knowledgeable and “tells,” rather than facilitates, or “draws out.” Advice-giving within coaching is not considered appropriate, nor is it in counseling. In mentoring it is a common misunderstanding of the mentoring process. Here is an important maxim: “Nobody ever took any advice unless they wanted to!” This is a serious point in mentoring. Advice-giving is only OK if the mentee asks for it or if it’s been agreed upon in advance as part of the mentoring process. Why? Because, if the mentor continually gives advice, the mentee may become dependent on the mentor and unable to stand on their own two feet! Also, the mentee may become resentful of it, and why would a mentor think that their advice is appropriate or necessary? It is far better to share experience as data to be discussed rather than advice to be followed!

In academic settings, program coordinators need to be prepared to differentiate academic advising from mentoring. It is common in the designing phase of program development for potential participants as well as stakeholders to wonder if a mentoring mission creeps into the role of an academic advisor. Dominguez and Kochan (2020) provide a schema that differentiates mentoring from academic advising: The only area both scored high on was career support. In the other dimensions of skill development, modeling, psychosocial support, and sponsorship and networking, mentoring scored high, while advising scored low. This makes intuitive sense because a mentor, when compared to a generalist advisor, is often more skilled and connected to a profession and professional network, which positions them to be an effective role model and offer comprehensive psychosocial support.

Given that these “helping activities” are, as I stated earlier, social constructions, this dynamic quality will result in a constant shifting of what we understand about their purpose, nature, and form.

In considering other development relationships, for example education and training activities, a main difference is that both coaching and mentoring tend to be individual activities, whereas education and training tend to be group activities. As I stated earlier in this chapter, Rousseau argued in 1772 that the ideal class size for education is one-to-one! Clearly, this represents an ideal; however, it is worth considering that a key value of mentoring is found in its individual orientation. In this way the subject matter under discussion is pertinent to the learner.

Defining Mentoring

So, what about a single definition of mentoring as it is currently—is there one? As one of my students once said, “That’s annoying isn’t it!” She’s right! This section is about why definition is a problem and how else this problem can be viewed and understood. I will start with the challenges of creating a single definition. I will then look at some different definitions from different contexts. Next, I will pull out the common themes in these definitions and then explore an alternative to definition by thinking about these common elements as dimensions of mentoring. Following the exploration of dimensions, I bring these different ideas on the dimensions together into an integrated framework (Figure 1.3) with the aim of it being of practical use in a range of contexts where mentoring might take place. From this, I will consider the idea of moving from definitions to descriptions in order to capture the main aspects of mentoring activity.

Challenges of Creating a Singular Definition of Mentoring

There is no universally agreed-upon definition of mentoring (Dominguez & Kochan, 2020) despite the calls from many quarters for such a thing. Dominguez and Kochan suggest that “providing stature for mentoring discourse, however, is an intricate process in and of itself” (2020, p. 4). One way to explore the intricacies of mentoring definitions, as Dominguez and Kochan suggest, is through the notion of discourses.

Discourses are ways in which people talk about things and they are ways of supporting and transmitting meaning through social contexts. Bruner (1996, p. 39) suggests that people have two main ways of developing a sense of meaning and organising their thoughts. “One seems more specialized for treating of physical ‘things’ the other for treating of people and their plights. They are conventionally thought of as logical-scientific thinking and narrative thinking” (p. 39).

The logical-scientific way would certainly hold with the notion of a universal definition for mentoring; however, this approach denies the socially constructed nature of mentoring. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine mentoring guide by Nora Beck Tan, entitled Understanding Your Role as a Mentor, recognizes this position when she states:

There is no one-size-fits-all formula for excellent mentorship of postdoctoral Research Associates. Each individual Associate has their own set of strengths, motivators, challenges, and dreams. Research Advisers are unique, too, learning and growing over time as researchers and mentors. As such, each mentoring relationship you are involved in will be unique and “the right” approach to each individual that you mentor will be different. (2020, p. 1)

Mentoring is a series of discourses or narratives located within a variety of social contexts and, as I discussed above in the previous section, it is put to various purposes within those contexts. Bruner argues that it is the people’s contexts and not biological factors that shape human lives and minds (Bruner, 1990, p. 33), and he goes on to say:

We shall be able to interpret meanings and meaning-making in a principled manner only in the degree to which we are able to specify the structure and coherence of the larger contexts in which specific meanings are created and transmitted. (p. 64)

Narratives involve language, and language, as a vehicle for communicating meaning plays an important part in human sense-making, as Webster (1980, p. 206) suggests: “Language is the primary motor of a culture” and “language is culture in action.” At the heart of discourse is interpretation, and it is very clear that one person’s interpretation is not the same as another’s. Any interpretation of mentoring, for example, has to be made by taking into account the social context in which it is employed and the purpose to which it is put. To illustrate this, here are a series of mentoring definitions found in a range of different contexts: “Mentoring is defined as an intense interpersonal relationship where a more senior individual provides guidance and support to a more junior organizational member.” (Kram, 1985, cited in Eby & Lockwood, 2005, p. 442).

In this definition, there are four main elements. The first is intense interpersonal relationship; the notion of intense is perhaps a value judgement. The second is that the relationship is positioned as senior to junior and this, therefore, implies experience and lack of experience and perhaps an assumption that the mentor is in the power position. The third is guidance and support, indicating what a mentor might do. The fourth element is the context, and in this case it is an organizational one.

Mentoring is a one-to-one, non-judgemental relationship in which an individual voluntarily gives time to support and encourage another. This is typically developed at a time of transition in the mentee’s life and lasts for a significant and sustained period of time. (Community Works, n.d.)

This definition has a social context in mind—the community. It emphasises non-judgemental, voluntary, support, and encouragement as key qualities and behaviors within the relationship. It also places an element of timeliness within the relationship and indicates that this relates to personal transitions. In this case, mentoring is aimed at helping social integration of migrant people coming to the United Kingdom. The holders of the power here are the UK home office. Governments do not invest money without an expectation of a social return. Social mentoring activity was a concept borrowed by the British government from the Big Brothers and Big Sisters program in the United States.

In the context of higher education in the United Kingdom, the following is employed by the Centre for Higher Education:

Mentoring is a protected relationship which supports learning and experimentation and helps individuals develop their potential. A mentoring relationship is one where both mentor and mentee recognise the need for personal development. Successful mentoring is based upon trust and confidentiality. (Centre for Higher Education Practice, n.d.)

The emphasis in this definition is learning and experimentation, the personal development of both parties to the relationship, and trust and confidentiality. The context is implied, given the location of the definition on a mentoring website for a university.

The next definition stresses knowledge sharing and articulates the key skills and behaviors associated with mentoring. Similarly, the context in this definition is also implied. It also clearly states what mentoring is not confined to, gives examples of who might be included, and positions the benefits of collegial support. The web page argues at length for the need for mentoring faculty:

Sharing knowledge with colleagues, providing support, listening to and responding to questions, and strategizing solutions to problems. Mentoring is not confined to one stage of a faculty member’s career but rather throughout it, as they take on new roles and follow their individual paths. And all faculty members—including both those who are not on the tenure track and those who are tenured—benefit from collegial support. (Misra et al. 2021)

Common Elements in Defining Mentoring

As can be seen from these examples, there are many ways in which people define mentoring, and it seems that there are five elements to the definition in general. The first element is to ask, what is the role of the mentor? This is sometimes specified in definitions; for example, giver of guidance and support, and in others it is implied; for example, helper, role model, guide. Second, what is the purpose of the mentoring activity? For example, sharing knowledge or dealing with transitions. Third, context, and it is here that the context is mostly implied by where the definition appears and, on occasions, it is specified; for example, with an organizational setting. Fourth, who is the mentoring is for? Fifth is the core skills of the mentoring.

The historical roots from the 18th century position mentoring as a fundamental and educative process. It was then, and in many cases still is now, a voluntary activity—that is, about learning and development. It is commonly set within a change or transitional situation for the mentee. Sometimes it is positioned as a mutual relationship where both parties learn and at other times there may be a career or performance orientation. Eby et al. (2007) argue, similarly to the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine quotation, that the mentoring relationship is unique to the participants and tends to be defined by the type of support offered within the relationship; this could include personal or emotional support. Johnson (2007) suggests that role modeling plays a part, and career outcomes are relevant. Garvey (1994a) points out that mentoring relationships are dynamic and change over time, and Eby et al. (2007) suggest that this is what creates the uniqueness of mentoring relationships. Given this, an alternative approach to definition seems appropriate and gives rise to the following question: How may these commonalities be used in your program?

Let’s now consider that question!

Dimensions of Mentoring

This section takes these commonalities and explores them through three pieces of research. The first makes use of my early research. Next, I draw on Salter’s (2013) doctoral research, and the third is Stokes et al. (2020). All three pieces of research identified that mentoring (and coaching) relationships appear to have dimensions. These are various points on a series of continuums.

I then bring these dimensions together into a framework that aims to help you position and define your own program.

Garvey’s Dimensions (1994)

Garvey (1994a) identified five dynamic dimensions within the mentoring relationship, which represent continuums to describe the relationship.

Figure 1.1

Mentoring Relationship Dimensions

Open …………………………………………ClosedPublic ………………………………………..PrivateFormal……………………………………….InformalActive………………………………………..PassiveStable………………………………………..Unstable |

Note. From Garvey (1994a, p. 18).

The Open/Closed dimension is related to what the participants talk about within the mentoring relationship. In the Open dimension there are no off-limits topics of conversation, but in the Closed dimension the content is contained to a specific set of topics.

The Public/Private dimension is about confidentiality or who knows about the relationship and what they may need to know.

The Formal/Informal dimension is about the administration or management of the relationship. Formality might be part of a mentoring program and the Informal may be a more natural relationship.

The Active/Passive dimension is about the expectations of the relationship in terms of who does what as a result of the mentoring conversation.

The Stable/Unstable dimension is about consistency in the process. All these dimensions may change over time, and regular review by mentor and mentee of these dimensions is necessary.

Salter’s Dimensions (2013)

Salter (2013) explored different perspectives on mentoring and coaching by interviewing people who identified with different forms of both mentoring and coaching. These included:

- executive coaching

- sports coaching

- coaching psychologists

- mentors of young people

- leadership mentors

- mentors of newly qualified teachers

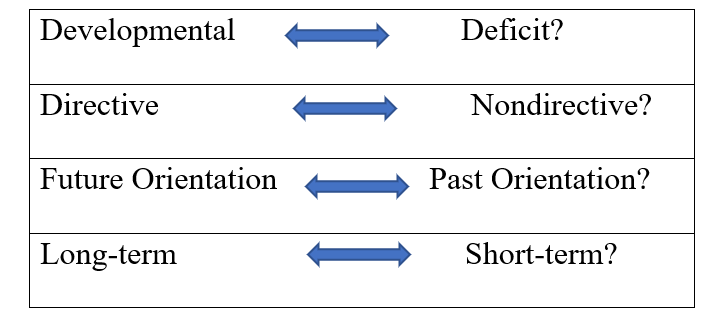

Salter (2013) found that role, purpose, and context influenced how the participants understood either coaching or mentoring within their own contexts. (The framework holds for both mentoring and coaching, but for clarity I will only use words linked to mentoring.) She characterized these as four dimensions, shown in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2

Salter’s Dimensions

Note. From Salter (2013).

The Developmental dimension assumes that the mentee has experience, knowledge, and skill. The mentor will work to develop and enhance the mentee’s experience, knowledge, and skills. This is a desirable state.

At the Deficit end of the continuum, the mentor assumes that the mentee does not have experience, knowledge, or skills and the mentoring will help to fill that gap. This may be where the mentor gives advice, tells the mentee what to do, or teaches them. This may be a good approach where needed, but if this is the mentor’s default, it can be a problem for the mentee.

The Directive, similar to the Deficit dimension, is where a mentor gives advice or instructions or tells the mentee what to do by simply assuming that this is the role of the mentor. As discussed earlier, this is not always a helpful way to mentor. The Nondirective end of the continuum is where the mentor enables the mentee to think things through for themselves and make their own decisions.

The Long-term/Short-term dimension is about the duration of the relationship. In some programs, this may be specified; for example, lasting 1 year, and in other situations it may be a life-long relationship.

Depending on the context, purpose, and roles performed by the mentor, the emphasis on these different ends of the continuum will change. However, a mentor always needs to keep in mind that the ultimate purpose as an educative and developmental process is to enable people to stand on their own two feet!

Stokes et al. (2020)

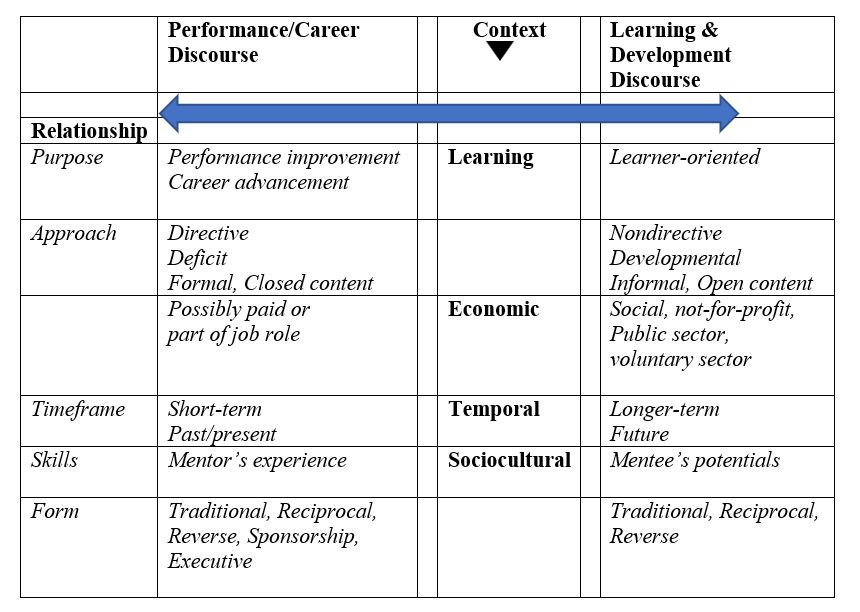

Reminiscent of Dominguez and Kochan’s (2020) reference to discourses in mentoring definitions discussed above, Stokes and colleagues explored the main discourses found in the literature about coaching and mentoring and based their dimensions on these discourses.

They called this approach a “continuum of meaning” to explain them. Their dimensions consider four contexts:

- Learning context

- Economic context

- Temporal context

- Sociocultural context

Within these contexts, the purpose, nature, timeframe, and skills employed are considered.

In the Learning context, they position “performance orientation” at one end of the dimension and “growth and learning” at the other. Much of the discourse in coaching is about performance, whereas in mentoring, it tends toward growth and learning. In the Economic context, they place “formal and paid” at one end and “informal and voluntary” at the other. The coaching discourse is often formal, where a coach may be external to the context of the coachee and subject to a contract and paid, whereas in mentoring it is often informal in contractual terms and voluntary. The Temporal context is about the time factor in both coaching and mentoring. At one end of the continuum is “high pressure” and at the other is “low Pressure.” Coaching is often high pressure with an expectation of results in the short-term, whereas in mentoring, the timeline is longer term and more relaxed and organic. Within the Sociocultural context they consider the skills used by the coach or the mentor. In coaching, the discourse is often about the expertise and skills of the coach and their formal training to be a coach, whereas in mentoring there is an emphasis on the job-related experience and knowledge of the mentor. In my view, mentoring is just as skilled as coaching, and mentor development is often ignored in programs.

Using the Dimensions

So, how may these dimension frameworks be helpful to you as a program leader? Garvey (2004) argues that there can never be universal agreement on the meanings of mentoring, coaching, or counseling, but that “in whatever setting the terminology is used, there needs to be a common understanding of meaning within that setting” (p. 8).

Keep this in mind because all participants in your program will need a common understanding of what is meant by mentoring in their context. This is very important because if they don’t know, it is a recipe for the whole program to fall apart!

Rather than a definition, try to think of a description of mentoring for your program. A description is more likely to help your mentors and mentees understand the needs of your program. To help you create your own description of mentoring for your own context, Figure 1.3 brings together the three dimension frameworks discussed above.

Figure 1.3

A Dimensions Approach to Definition of Mentoring

First, ask yourself, “What is the main purpose of the mentoring in my program?”

Performance or Career

For the learning context, the content of the mentee’s learning will be things to improve their performance or advance their career. The approach to facilitating this is likely to be more directive, deficit, and formalized. The subjects for discussion are likely to be on the Closed end of Garvey’s (1994a) dimensions.

For the Economic context, the mentor may be external to the organization, paid, or it might be part of their job role.

In the Temporal context, the timeframe of the relationship is likely to be shorter and deal with the present and possibly past experiences.

For the Sociocultural context, the emphasis on the mentor’s skills will be their experience—you will need mentors who have the relevant experience.

The form the mentoring takes will be traditional, reciprocal, reverse, sponsorship, or executive mentoring as discussed above. The mentor’s focus is likely to be on the organizational context and what is good for the organization.

These may change as the relationship progresses and it’s possible that the relationship may not position itself at the extreme end of the continuum.

Learning and Development

For the Learning context, the content of the mentee’s learning will be related to their agenda and things they would like to learn. On Garvey’s (1994a) dimensions, the subject matter will be Open and determined by the mentee.

For the Economic context, the approach that is likely to be taken in the relationship is more Nondirective, Developmental, and on a more informal basis.

For the Temporal context, the timeframe of the relationship is likely to be longer term, possibly a year or more. The temporal perspective will be the mentee’s future.

For the Sociocultural context, the emphasis is on the mentor’s skill in drawing out the mentee’s potential.

The form the mentoring takes will be traditional, reciprocal, reverse, sponsorship, or executive mentoring as discussed above.

These may change as the relationship progresses and it’s possible that the relationship may not position itself at the extreme end of the continuum.

Current State of Mentoring in Academia

Unsurprisingly, mentoring is widespread in academia and in particular higher education (HE). Mentoring takes on many forms in this context, for example:

- undergraduate mentoring

- graduate mentoring

- faculty mentoring

- staff mentoring

- self-mentoring

Undergraduate Mentoring

There are several different mentoring arrangements found in the category of undergraduate mentoring (see Chapter 16). One arrangement is where third-year students may mentor second-year students and second-year students may mentor first-year students. Another is where undergraduate students may volunteer to mentor in high schools and in some cases in primary schools. These arrangements can take the form of one-to-one relationships or groups.

Example

If the arrangement is undergraduate students mentoring in high schools as volunteers, the purpose of the mentoring is learning and development with the intent to help high school students understand something about university life, and the descriptive definition would be influenced by the right-hand column of Figure 1.3.

Mentoring is a year-long program to help the high school student understand the expectations of university life and to help them think about any worries they may have about entering university. It will involve the mentor asking questions and listening to the high school student so that he or she may enter university confidently.

From this description, your mentors and mentees will know who it is for, how long it will last, the purpose of it, the skills needed, and its ultimate aim. Any questions the mentors may have during their initial training can be answered with reference to the right-hand column of Figure 1.3. Similarly, any issues the mentee may have before starting can be answered with reference to the right-hand column.

Graduate Mentoring

An example here may be with graduate students mentoring undergraduates and, similar to the undergraduate arrangements, graduates may volunteer to mentor in schools (see Chapters 20 and 21). In some universities, graduate students may have mentoring arrangements with colleagues in an industry.

Example

The example here is colleagues in an industry mentoring the graduate student. The purpose of the mentoring is career development to prepare the graduate student for entry into the workplace. The descriptive definition would be influenced by the left-hand column of Figure 1.3.

Mentoring is an opportunity for Postgraduate students to engage with professionals from the relevant industry for a period of 3 months. The mentor will focus on job-related issues and questions that the mentee may have. The mentor will share their experiences with the mentee to enable them to enter the workplace with confidence.

Like the last example, your mentors and mentees will know who it is for, how long it will last, the purpose of it, the skills needed, and its ultimate aim. Any questions the mentors or mentees may have during their induction can be answered with reference to the left-hand column of Figure 1.3. The other temporal aspect is that the discussions are more likely to be around the past and the present.

Faculty Mentoring

There are different forms of mentoring arrangements with faculty (see Chapters 22-24). One may be an onboarding mentoring process where a newly appointed academic may get a mentor to support them in the first year or two of starting work in a university. Another may be where faculty members may have a “thinking partners” relationship with each other. This may take the form of a peer mentoring or reciprocal mentoring arrangement. Here, the two parties may provide mutual sounding-board support for each other.

In some universities, mentoring is employed to support faculty as they develop a research profile. The mentor may be an experienced researcher who may support the less-experienced researcher to develop their research ideas and to support them to get their work published.

In other universities, mentoring may be employed to assist the mentee to develop their career. In particular, this may be about gaining promotion or tenure.

In some universities, mentoring is employed for faculty to support a diversity agenda. Here the mentoring may be about supporting women or various ethnic groups to progress in the university system.

Example

The example here is mentoring faculty women of color for career advancement. The mentoring is to help the mentee navigate the social and political environment. This would include helping the mentee cope with microaggressions, oppression, and negative stereotyping in order to increase their confidence and positive self-identity.

Mentoring offers one-to-one support for women of color within the university as well as offering access to a wider network of mentors through our consortium and national networks. The mentoring provides an opportunity to learn and discuss social and political issues that may act as barriers to the mentee’s career progression. The form and type of mentoring can be adapted to suit the mentee’s needs; be this hierarchical, peer, reciprocal, reverse, or networked.

This description offers a clear purpose but also considerable flexibility in the form the mentoring could take. Central to this program is the mentee’s needs. This description is based on research by Tran (2014) that suggests a flexible and networked approach is appropriate for this type of mentoring.

Staff Mentoring

Staff in universities may have mentoring support for a variety of purposes, for example:

- onboarding

- career development

- diversity agendas

The form of mentoring could be peer or reciprocal (see Chapters 25 and 26).

Example

The example here is peer mentoring aimed at improving colleagues’ understanding of diversity issues. The relationship is reciprocal. The primary purpose is part of a learning and development agenda. This takes us down the right-hand column of Figure 1.3.

Mentoring is a confidential relationship between two colleagues based on a mutual desire to understand social and cultural differences. It is additional to other forms of development offered within the university. Mentoring is a nondirective, nonjudgemental relationship that is broadly focused. The approach is aimed at systemic and individual change and is about creating genuine understanding of each other’s lived experiences.

In this description, the confidential nature is stressed first. In this type of program, this is essential. Mutuality is also stressed, as are the nondirective and nonjudgemental aspects. The timeline isn’t mentioned in this description; however, it could be assumed that this is a longer-term relationship, and the discussions are about the future. The aim is systemic and individual change, so there is an organizational and individual focus. As both participants are both mentor and mentee to each other, the aim is mutual understanding and the development of the mentee’s potentials.

Self-Mentoring

Self-mentoring is a relatively new development in mentoring. Described as:

A learner of any age, profession, gender, race, or ability who is willing to initiate and accept responsibility for self-development by devoting time to navigate within the culture of the environment in order to make the most of opportunity to strengthen competencies needed to enhance their leadership skills. (Carr et al., 2017, p. 120).

Self-mentors do not work in isolation, as the name suggests. Instead, self-mentoring is a process that may enlist others, as needed, to provide feedback and comment; however, it is essentially a self-reflective activity aimed at developing individual agency.

Although it is clear that mentoring can take many forms within the higher education sector, it is also clear that not all universities provide adequate and appropriate support for mentors in the form of professional development activities.

Developing Mentoring in HE

How might you develop mentoring in your institution?

Pololi and Knight (2005) found that a lack of good mentors may hinder an academic’s career progress. Lindén et al. (2010) found that the degree of reciprocal learning was dependent on the behaviors of the mentor. To tackle these issues, Merrick and Stokes (2003) and Colley (2003) argue that the design of any mentoring program is critical to its success. A key question to ask at the outset is “whose agenda is it?” Colley (2003) argues in relation to social mentoring schemes that there are “often unacknowledged power dynamics at work such as, class, gender, race, disability, sexuality that may either reduce or reproduce inequalities” (p. 2).

Colley goes on to argue that unless this issue is addressed, the mentoring arrangements may not develop in positive ways. This is potentially a problem in all the mentoring arrangements raised above. Making use of Figure 1.3 may go a long way to help resolve this issue.

One such problem is that of advice-giving. Rosinski (2004), writing from a coaching perspective, suggests that mentoring is, potentially, at least, about gratuitous advice-giving, but as Moberg and Velasquez (2004) argue, advice is “potentially transformative.” Advice should be relevant, address the issue under discussion, and be presented as an option for debate. Mentors who appreciate this may hold back on advice-giving, and this appreciation could also come from appropriate professional development of the mentors.

A mentor offering challenges to the mentee is an important aspect of the mentee’s development, but challenge without support could be another problem. This could be ameliorated through the professional development of the mentors.

Consideration is also necessary regarding how each pair is matched. Megginson et al. (2006) suggest voluntary matching but also matching in relation to the program’s purpose and, as a preference, for a small degree of difference between the pair (see Chapter 9 for a detailed discussion on matching).

It is clear that the professional development of mentors is important. Giebelhaus and Bowman (2002) and Pfund et al. (2006) find that mentors who are supported and developed for the role have statistically significantly better results than those that are not, and with this in mind, Ramani et al. (2006 pp. 404–407) offer the following practical tips for mentor development:

- Mentors need clear expectations of their roles and enhanced listening and feedback skills.

- Mentors need awareness of culture and gender issues.

- Mentors need to support their mentees but challenge them too.

- Mentors need a forum to express their uncertainties and problems.

- Mentors need to be aware of professional boundaries.

- Mentors also need mentoring.

- Mentors need recognition.

- Mentors need to be rewarded.

- Mentoring needs protected time.

- Mentors need support.

- Encouraging peer mentoring unloads the mentor.

- Continuously evaluate the effectiveness of the mentoring program.

It is also important, as in the example of the faculty mentoring program described above, to explore alternative and new forms of mentoring such as reciprocal, peer, networked, or self-mentoring.

Future Research Considerations in Academia

There is an abundance of research publications on mentoring in higher education. To date, much has focused on the potential efficacy of mentoring (see for example: Tagirova et al., 2020; Mazerolle et al., 2018; Muschallik & Pull, 2016 Gimmon, 2014). These types of evaluative studies on mentoring in higher education date back to the 1990s and as can be seen by the above examples, chosen at random, it persists. Although this approach to research has yielded some helpful insights into various forms of mentoring within the sector and has provided support for the notion that mentoring can and does work, it would seem that little attention has been paid to the issue of program design and mentor development as well as the use of online mentoring, and there is little on the potential power dynamics at play in mentoring in higher education and how it might work. Additionally, the question of ethics within mentoring in the sector is rarely considered.

Summary and Conclusion

This chapter has covered a considerable amount of terrain in relation to mentoring. I first explored the historical development of mentoring and concluded that mentoring’s roots are in education, learning, and development. I then explored the similarities and differences between mentoring and other helping behaviors. Then I tackled the problems of defining mentoring. Due to its social constructivist nature, there are many variations, however, it is clear that the purpose and the context help to shape definition.

To overcome the problem of definition, I then explored the idea of dimensions in mentoring and how to use these in practice.

Then I looked at applications of mentoring within academia and again noted that there are many variations of practice; however, there was a lack of development and ongoing support for mentors in HE and the section concludes with some practical help on developing mentoring within the HE sector.

The question of research on mentoring in the HE sector is then considered, and I look at some suggestions for possible areas where more research is needed.

Overall, this chapter tracks the development of mentoring through into the HE sector, from its earliest beginnings in 18th-century France, and I can only conclude that something that has been around and involved in education for so long must have something going for it!

References

Alred, G., & Garvey, B. (2000). Learning to produce knowledge: The contribution of mentoring. Mentoring and Tutoring, 8(3), 261–272.

Alred, G., & Garvey, B. (2019). The mentoring pocket book (4th ed.). Management Pocket Books.

Bruner, J. (1990). Acts of meaning. Harvard University Press.

Bruner, J. (1996). The culture of education. Harvard University Press.

Carr, M. L., Holmes, W., & Flynn, K. (2017). Using mentoring, coaching, and self-mentoring to support public school educators. The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 90(4), 116–124.

Centre for Higher Education Practice. (n.d.). What is mentoring? University of Southampton. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.southampton.ac.uk/chep/mentoring/what-is-mentoring.page

Clutterbuck, D. (1985). Everyone needs a mentor: Fostering talent in your organisation. IPM.

Clutterbuck, D. (1992). Everyone needs a mentor: Fostering talent in your organisation (2nd ed.). IPM.

Colley, H. (2003). Mentoring for social inclusion: A critical approach to nurturing mentoring relationships. Routledge Falmer.

Community Works. (n.d.). Mentoring programme increases community leaders’ skills and confidence. Brighton and Hove Community Works. Retrieved April 24, 2022, from https://www.bhcommunityworks.org.uk/mentoring-programme-increases-community-leaders-skills-and-confidence/

Dominguez, N., & Kochan, F. (2020). Defining mentoring. In B. J. Irby, L. Searby, J. N. Boswell, F. Kochan, & R. Garza (Eds.), The Wiley International handbook of mentoring: Paradigms, practices, programs, and possibilities. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Eby, L. T., & Lockwood, A. (2005, December). Protégés’ and mentors’ reactions to participating in formal mentoring programs: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 67(3), 441–458.

Eby, L. T., Rhodes, J. E., & Allen, T. A. (2007). Definition and evolution of mentoring. In T. A. Allen & L. T. Eby, The Blackwell handbook of mentoring. Blackwell Publishing.

Fénelon, F. (1808). The adventures of Telemachus (J. Hawkesworth, Trans.; 2nd English ed., Vols. 1 and 2). Union Printing Office.

Garvey, B. (1994a). A dose of mentoring. Education and Training, 36(4), 18–26.

Garvey, B. (1994b). Ancient Greece, MBAs, the health service and Georg. Education and Training, 36(2), 18–26.

Garvey, B. (2004). Call a rose by any other name and it might be a bramble. Journal of Development and Learning in Organisations, 18(2), 6–8.

Garvey, B. (2017). Philosophical origins of mentoring: The critical narrative analysis. In D. Clutterbuck, A. McClelland, F. Kochan, L. Lunsford, & B. Smith (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of mentoring. SAGE.

Garvey, B., & Alred, G. (2001). Mentoring and the tolerance of complexity. Futures, 33(6), 519–530.

Garvey, B., & Stokes, P. (2022). Coaching and mentoring theory and practice (4th ed.). Sage.

Gay, B., & Stephenson, J. (1998). The mentoring dilemma: Guidance and/or direction? Mentoring and Tutoring, 6(1-2), 43–54.

Giebelhaus, C. R., & Bowman, C. L. (2002). Teaching mentors: Is it worth the effort? Journal of Educational Research, 95(4), 246–254.

Gimmon, E. (2014). Mentoring as a practical training in higher education of entrepreneurship. Education and Training, 56(8/9), 814–825.

Harquail, C. V., & Blake, S. D. (1993) UnMasc-ing mentor and reclaiming Athena: Insights for mentoring in heterogeneous organizations [Paper 8]. Standing Conference on Organizational Symbolism, Collbato, Barcelona, Spain. www.scos.org

Higgins, M. C., & Kram, K. E. (2001). Reconceptualizing mentoring at work: A developmental network perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 264–288.

Mabie, H. W., (1913) The Mentor, A Wise and Faithful Guide, Vol.1, 1-200.

Misra, J., Kanelee, E. S., & Mickey, E. L. (2021, March 18). Institutional approaches to mentoring faculty colleagues. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2021/03/18/colleges-should-develop-formal-programs-mentoring-not-leave-it-individual-faculty

Irby, B., & Boswell, J. (2016). Historical print context of the term “mentoring.” Mentoring and Tutoring, 24(1), 1–7.

Johnson, W. (2007). Student‐faculty mentorship outcomes. In T. Allen & L. Eby (Eds.), The Blackwell handbook of mentoring (pp. 189–210). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Jones, T. (2015). Chaucer’s knight: The portrait of a medieval mercenary. Methuen.

Kram, K. E. (1985). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Scott, Foresman.

Lattimore, R. (1965). The odyssey of Homer. Harper Perennial.

Lean, E. (1983). Cross-gender mentoring: Downright upright and good for productivity. Training and Development Journal, 37(5), 61–65.

Lee, A. W. (Ed.). (2010). Authority and influence in eighteenth-century British literary mentoring. In Mentoring in eighteenth-century British literature and culture (pp. 1–17). Ashgate Publishing Company.

Levinson, D. J., Darrow, C. N., Klein, E. B., Levinson, M. H., & McKee, B. (1978). The seasons of a man’s life. Knopf.

Lindén, J., Ohlin, M., & Brodin, E. (2010). Mentorship, supervision and learning experience in PhD education. Studies in Higher Education, 38, 639–662.

Lunsford, L., Crisp, G., Dolan, E., & Wuetherick, B. (2017). Mentoring in higher education. In D. Clutterbuck, A. McClelland, F. Kochan, L. Lunsford, & B. Smith (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of mentoring. SAGE.

Mazerolle, S. M., Nottingham, S. L., & Barrett, J. L. (2018). Formal mentoring in athletic training higher education: Perspectives from participants of the National Athletic Trainers’ Association foundation mentor program. Athletic Training Education Journal, 13(2), 90–101.

Megginson, D., Clutterbuck, D., Garvey, B., Stokes, P., & Garrett-Harris, R. (2006). Mentoring in action (2nd ed.). Kogan Page.

Merrick, L., & Stokes, P. (2003). Mentor development and supervision: A passionate joint enquiry. International Journal of Coaching and Mentoring (e-journal), 1. www.emccouncil.org

Moberg, D. J., & Velasquez, M. (2004). The ethics of mentoring. Business Ethics Quarterly, 14(1), 95–102.

Muschallik, J., & Pull, K. (2016). Mentoring in higher education: Does it enhance mentees’ research productivity? Education Economics, 24(2), 210–223,

Pfund, C., Pribbenow, C. M., Branchaw, J., Miller Lauffer, J., & Handelsman, J. (2006, January). The merits of training mentors. Science, 311, 473–474.

Pololi, L., & Knight, S. (2005). Mentoring faculty in academic medicine. A new paradigm? Journal of General Internal Medicine, 20(9), 866–870.

Purkiss, J. (2007). Squires to knights: Mentoring our teenage boys. Self-published, Xulon Press.

Ramani, S., Gruppen, L., & Kachur, E. K. (2006). Twelve tips for developing effective mentors. Medical Teacher, 28(5), 404–408.

Revans, R. W. (1983). ABC of action learning. Lemos and Crane.

Riley, P. (1994). Fenelon: Telemachus. Cambridge University Press.

Roberts, A. (1998). The androgynous mentor: Bridging gender stereotypes in mentoring. Mentoring and Tutoring, 6(1–2), 18–30.

Roberts, A. (2000). Mentoring revisited: A phenomenological reading of the literature. Mentoring and Tutoring, 8(2), 145–170.

Rolfe, A. (2021). Mentoring: Mindset, skills and tools (4th ed.). Mentoring Works, Synergetic People Development Pty Limited.

Rosinski, P. (2004). Coaching across cultures. Nicholas Brealey.

Salter, T. (2013). A comparison of mentor and coach approaches across disciplines [Unpublished doctoral thesis]. Oxford Brookes University.

Starr, J. (2014). The mentoring manual: A step by step guide to becoming a better mentor. Pearson Education.

Stelter, R. (2019). The art of coaching dialogue: Towards transformative exchange. Routledge.

Stokes, P., Fatien Diochon, P., & Otter, K. (2020, February 21). “Two sides of the same coin?” Coaching and mentoring and the agentic role of context. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1483(1), 142–152. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/32083348

Tagirova, N. P., Yudina, A. M., Krasnova, L. N., Gorbunov, M. A., Shelevoi, D. G., Spirina E. V., & Lisitsyna, T. B. (2020). Mentoring in higher education: Aspect of innovative practices interaction in development of student professional and personal competencies. Eurasian Journal of Biosciences, 14, 3617–3623.

Tan, N. B. (2020). Mentoring guide #1: Understanding your role as a mentor. National Academies. https://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/pgasite/documents/webpage/pga_365027.pdf

Tran, N. A. (2014). The role of mentoring in the success of women leaders of color in higher education, mentoring & tutoring. Partnership in Learning, 22(4), 302–315.

Webster, F. (1980). The new photography: Responsibility in visual communication. John Calder.