2 Recognizing Mentoring Program Identity and Applying Theoretical Frameworks for Design, Support, and Research

Mark J. Hager; Kim Hales; and Nora Domínguez

Abstract

Mentoring programs in academic settings take multiple forms depending on the population being served, the context in which they develop, and the purpose and outcomes to be achieved. This chapter identifies critical variables in choosing a solid theoretical foundation for designing effective mentoring programs and interventions in academia.

This chapter specifically addresses four clusters of theoretical frameworks that include psychosocial supports for mentoring, mentoring as a learning partnership, mentoring as career support, and developmental network theories that can be applied to careers.

This chapter is broken into four distinct sections. The first section outlines the process of identifying key components and variables of an individual mentoring program. In the second section, we present two broad categories of frameworks to assist readers in customizing the appropriate theoretical framework that will align their program’s needs and goals with their program’s local mentoring identity. Section three explains and gives examples of the process for connecting the customized frameworks to the practice of a mentoring program. Finally, section four will share our thoughts on updating, rearticulating, and creating new frameworks to develop a research design to increase stakeholder support of individual programs and contribute to the important body of knowledge regarding university mentoring programs.

Correspondence and questions about this chapter should be sent to the first author: mhager@menlo.edu

Acknowledgments

Don Busenbark for help with graphic images.

David Law for consultation and input.

Introduction

Mentoring relationships in higher education have been shown to increase student persistence to degree and program satisfaction (Mullen et al., 2010). In addition, early career faculty have experienced greater job satisfaction when they judged their mentoring relationships to be higher quality (Lunsford et al., 2018). Similarly, higher-quality relationships were also related to enhanced scholarly productivity (Ogunyemi et al., 2010). Our focus for this chapter is mentoring relationships that support undergraduate and graduate students in developmental relationships with faculty, peers, and other developers within their broader academic and personal communities. Our goals for this chapter are to help you, program directors, and leadership to:

- Engage with a set of reflective questions to help you articulate your mentoring program’s identity within your institution and the larger landscape of higher education;

- reflect upon key theoretical frameworks for the myriad ways mentoring may be enacted in higher education, which you may adopt and adapt to help you enact your identity to achieve your goals;

- design theory-based activities and structures that support mentors and mentees; and

- analyze your program’s outcomes to ensure your activities align with your identity and achieve your goals, plan for growth and development, and inform internal and external audiences, including funders, accreditors, and the larger community of mentoring practitioners and scholars.

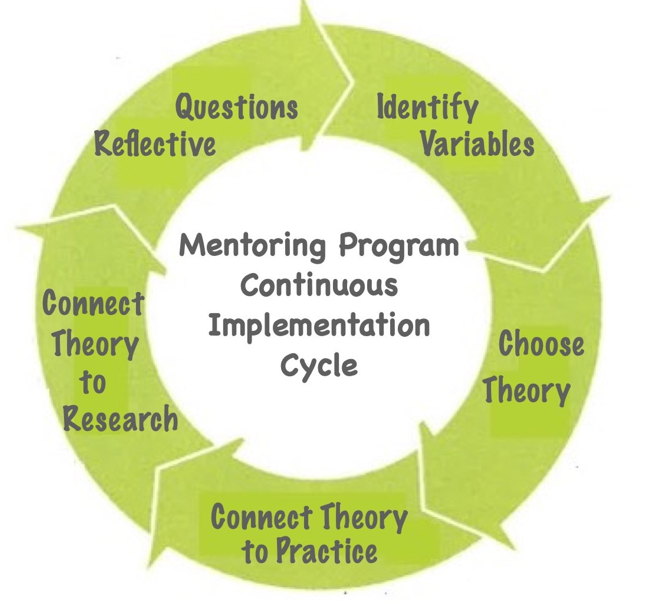

This five-stage approach is detailed in the Appendix. From this section and our diagram, you will see that we propose a cyclical and iterative process of what may be called a continuous improvement cycle. Reflection on big programmatic questions leads to identifying variables of your mentoring theory. From there, you are ready to analyze and select appropriate theories to guide your work and build program activities grounded in your theories. Once you have done those steps, you may assess your process and outcomes to inform future program growth and outside supporters. You may return to this process often over the course of your program’s design, growth, and continuation.

This chapter outlines the process of identifying key components of variables of an individual mentoring program and choosing the appropriate theoretical framework that aligns the program’s needs and goals with your local operational definition of mentoring. The chapter also explains the process for aligning the variables, frameworks, and definitions to determine the nature, scope, and identity of a mentoring program.

The proposed framework poses guiding reflective questions to define the purpose (why), the participants (who), the context (where), the objectives and outcomes (what), the processes involved (how), and the time frame of the program (when) while linking each element to the most fitting theoretical framework for practical applications, assessment, and programmatic research.

Under the premise that your program’s identity and guiding theoretical framework drives the structure and content of your intervention, in this chapter we explore mentoring relationships first as providing psychological and social support to help students join and engage with their academic communities; we explore Kram’s psychosocial functions and Tinto’s theory of social integration. It then moves into mentoring as a learning partnership and brings adult, developmental, social, and organizational learning theories to understand the characteristics and needs of the participants. We then explore career support theories to explain the milestones, transitions, and trajectories in academic careers, with the purpose of designing programs that provide systematic support for academic and personal growth and development. Our final area of mentoring theories embraces expansive developmental networks of peers, mentors, and collaborators. In the 21st century, with opportunities to collaborate globally, networks of mentors and developers can make important contributions to academic and career success.

We conclude by emphasizing the need for a paradigm shift from transactional relationships to relationships and programs grounded in greater reciprocity and mutuality. We also propose a translational model connecting theory to practice and practice to research for success in the dynamic landscape of mentoring in higher education.

This chapter will help mentoring program directors and their supporters identify the key mentoring theories and frameworks that make their programs succeed and which theories and frameworks they might add, change, or remove to better serve their goals and achieve their own definitions of mentoring success. To help achieve those goals, we will present a framework for identifying a local definition of your theory of mentoring that serves your program’s unique nature and scope. This entire book has valuable information for the many different dynamic strcutures of mentoring relationships, faculty mentoring, peer mentoring, and student mentoring. The concepts covered in this chapter easily apply to all they various dynamics; for clarity, we will focus on student mentoring by faculty in our discussions and examples and leave it to the program directors to individualize the information to their specific mentoring dynamics. Existing models of mentoring may help you place your program into one of many areas:

- Psychosocial support systems (Kram, 1985; Tinto, 2012)

- Learning partnerships that afford participants and communities to develop both hierarchical and more reciprocal relationships and networks (Kolb, 2014)

- Career developmental theories that consider milestones within individual career trajectories

- The importance of developmental networks to growing and sustaining a career in the academy (Griffin et al., 2018)

It is important here to acknowledge mentoring theory’s rich theoretical foundations drawn from many disciplines. Throughout this chapter we will highlight theories drawn from organizational science, psychology, human development, and education that are relevant to mentoring in academic settings and how they may inform programming and practice. We further recognize—and celebrate—that your unique identity and theoretical frame may borrow from several interwoven theories and disciplines. We have included several strategic citations and resources throughout this chapter, which you may find useful to consult as you build your theoretical framework. For example, programs often adopt a model to support mentees in career success and/or psychosocial growth, providing foundational mentoring functions long known to support individual growth (Kram, 1985). In today’s 21st-century academy, mentoring conversations may embrace several focal elements drawn from many of the theories we will discuss. Program directors, mentors, and mentees may also address the ever-increasing diversity in higher education and incorporate programs to embrace the rich skillsets and experiences individuals bring to their academic identities (Clutterbuck et al., 2012).

To conclude, we will return to these many theories of mentoring to propose a paradigm shift from transactional and hierarchical relationships to greater reciprocity and mutuality between and among mentors, mentees, and other developers participating in these relationships and programs. We will further propose—even challenge—program directors to adopt a translational model where mentoring theory may inform practice and local practices may inform programmatic and field research.

Identifying Key Components and Variables of an Individual Mentoring Program

Mentoring programs in higher education often start as grassroots initiatives driven by locally identified needs, program goals, or institutional initiatives. Your own programs may have begun with identifying a need to support student success, for which a mentoring program could offer a solution. An institutional or systemic call for mission-centric student engagement may prompt new mentoring initiatives. In each of these cases, we suggest your first step is to reflect upon those goals to establish your program’s identity. Our reflective questions will help you develop your program’s identity as you determine which theoretical frameworks best support programming that achieves your goals.

We encourage you to start your reflective process with an eye to the kinds of assessment that will serve you and your program best. Designing for formative assessment early will help you monitor your planning and progress, while summative assessment plans will help you prepare to collect and analyze ongoing process and outcomes data (see Chapter 13 for more on assessment, evaluation, and research). Some institutions, such as land-grant or state-funded universities, may be required to articulate and demonstrate achievement of measurable outcomes related to public funding. Private foundations or other internal and external community partners may also require data to support initial participation or continued support.

Here we pose reflective questions to help define your purpose (why), participants (who), context (where), objectives and outcomes (what), processes involved (how), and time frame of your program (when).

- Why do we mentor the way we do?

- Why does our institution need to offer this type of support to students? Why does mentoring seem like a good idea for our campus? Why are we considering this program?

- Who participates in and benefits from our mentoring initiatives or activities?

- Who is our target audience of mentors and mentees? For example, does our program model feature faculty mentors with undergraduate or graduate student mentees? Do you wish to promote a more distributed mentoring model within networks of developers or communities?

- Where do we situate mentoring within our local institutional context?

- Where do resources, opportunities, and constraints in our context inform our programming model? Where is our program housed and supported? Is it situated in a student affairs department? Is our program institution-wide, enjoying and drawing resources from multiple constituencies? Are you reading this chapter because your program is struggling to find a home—and support—in your community?

- What are our program goals, objectives, and outcomes (see Chapter 8 for more on goals, objectives, and outcomes)?

- Answers to who and why may help you answer this question. What measures will you use to demonstrate program and mentor/mentee success? For example, are your goals based on metrics and milestones that demonstrate successful matriculation into and completion of your degree programs? Are you helping mentees engage with their particular scholarly communities as they develop academic and professional skills? Do your goals include psychosocial support for vulnerable populations to assure them the greatest opportunities for success?

- How does our program accomplish its goals? How do we know it is working?

- How do you engage your mentors and mentees in the activities that embrace your identity? What activities or community practices do you build into programming or support for mentors and mentees?

- When is our timeframe for our programming?

- Some programs are designed as long-term relationships across a student’s academic career, while others are meant to provide more short-term initiatives and interventions. The context of your program may also influence timing if you are responding to welcome funding and support opportunities, such as a call for proposals for new models of student support.

Considering these reflective questions helps program designers, managers, and support staff craft their program’s identity, so they may clearly state what their programs are about—and what they are not meant to do. Here is a sample identity statement to help you get started:

Community college transfer students sometimes have trouble adjusting to their new home colleges or universities (why). Our 1-year (when) mentoring program pairs faculty leaders with entering undergraduate transfer students (who) to provide them with strong social support networks (what) as they integrate into our 4-year college community. Our program is housed in the Office of Student Affairs (where). With our objective of strong social support, we encourage mentors to introduce their mentees to colleagues and peers who share their academic and social interests to provide a strong network of support from a variety of sources (how). Some of our program activities (how) include transfer student mixers and special club and organization activities celebrating our transfer students and their place in our college community.

Once you draft your identity statement, we invite you to explore the numerous theoretical frameworks applied to mentoring in higher education. As you read through the frameworks, consider how their overall goals of psychosocial support, learning, career support, and development in social networks resonate with and reflect your own goals. If you already have a program designed, our model of programmatic change for this chapter may be one of “reverse engineering” as we move from these reflective big questions helping you identify your initial program identity and philosophy to theoretical frameworks that may inform or explain your design. From there, we suggest practical applications to embody your program identity as you newly understand it from the theoretical frameworks. Situating your supporting activities in your identity and theory can help translate them into program outcomes and metrics of success. How you achieve your metrics will reflect your identity and theories. Your outcomes may inform future program development, and you may need to share your analyses with internal and external audiences such as funders. Finally, we will encourage you to share your findings with other program directors and designers as part of the larger translational conversations among researchers and practitioners as we build the body of mentoring knowledge.

Mentoring was heralded in the 1970s with the aphorism, “Everyone who succeeds has had a mentor or mentors.” (Roche, 1979). With this chapter and this book, we hope program directors will be able to identify the pathway or structure of how everyone succeeds in their unique mentoring settings.

Using Frameworks to Identify Program Needs

In this section, we will discuss popular, long-standing models of mentoring that may be present in your own programs. Then we will discuss how understanding these models will allow you to apply them effectively to your new or existing programs. This section will present theoretical frameworks in four sections, (a) mentoring as a psychosocial support system, (b) mentoring as a learning partnership, (c) mentoring as a support for career development, and (d) mentoring as a component of developmental networks.

Mentoring as a Psychosocial Support System

Psychosocial theories provide program directors and participants with language and images of ways to engage in mentoring relationships that attend to the softer, relational side of mentoring. Psychosocial support provides mentees with a sense of belonging and contributes to social integration into their new academic community. We describe Kram’s (1985) theory of psychosocial functions and Tinto’s (2012) theory of social integration below, along with short examples. As you read through these theories, ask yourself if they capture the relationship goals and activities that exemplify the mentoring theory within your existing programs or if they sound like what you wish to pursue as you design your program.

Kram’s Model of Psychosocial Support Functions. Role modeling acknowledges the importance of having one or more models of a successful career and life in the academy on whom the mentee wishes to model their own career (Hager & Weitlauf, 2017). In more recent research, role modeling may stand separate from and complementary to psychosocial functions (Crisp & Cruz, 2009), but we discuss it here with psychosocial support; it may look like having someone to look up to who demonstrates how one successfully engages with and navigates academic communities. Acceptance and confirmation demonstrate that the mentor supports, respects, and affirms the mentee’s identity and skills in their relationships and organization. It may look like a mentor affirming the mentee’s knowledge in research, or it may mean showing trust in the mentee’s judgment related to pedagogical innovations. Important for today’s higher education communities, it may also mean affirming that a mentee from an underrepresented group, such as a first-generation scholar or minoritized individual, truly belongs in the academy and institution.

Counseling support offers a nonjudgmental listener and sounding board; it may look like listening to and providing support for your mentee’s academic or career insecurities and being ready to refer students to campus resources for more personal concerns. Finally, friendship is a unique personal quality, maintaining a friendly association beyond the campus and being more mutual and less hierarchical. It may look like shared informal conversations about mutual interests and shared social networks, or it may look like each bringing the other into their separate spheres.

Tinto’s Social Integration Theory (2012). This theory proposes that students who are more integrated into the academic and social activities and communities in their colleges or universities are more likely to remain actively engaged and persist to completion. Mentoring programs that embrace a social integration framework provide structures and processes that support students joining social and academic interest groups, including developing relationships with mentors, coaches, and role models. Social integration theories may work well with social or developmental network theories as students may find models of identities within networks across the program and institution.

Program directors who design for social integration may guide students to relevant clubs and campus organizations. Students from underrepresented groups may find this especially affirming if they see others who share their identities integrated into and flourishing in the community.

Mentoring as a Learning Partnership

Kolb (2014) suggests that mentoring be structured as an experiential part of education. This service learning theory posits mentoring as a learning partnership that presents the mentor as more of a facilitator to the mentee’s learning processes and presumes the mentee will take on roles and behaviors that demonstrate self-directed learning to provide for their own personal and professional growth. This type of mentoring framework benefits both the mentee and the mentor. Theories we explore here include: adult learning, behaviorism, cognitivist, constructivist, action learning, and transformative learning.

Learning Theories. In this section, we will briefly describe examples of learning theories; citations for each are included on the reference page for deeper investigation.

Adult Learning. Based on the work of Knowles and his colleagues (2014), the mentee is self-directed in their learning and reflects upon current and past experiences. These mentees adapt their learning to their contexts with internally driven purpose while mentors play a facilitating role. Mentoring in this context may look like mentors encouraging their mentee’s self-direction and independence to demonstrate support and confidence in their mentee’s abilities

Behaviorist. Peel (2005) acknowledged that learning and behavioral changes could occur via positive and negative consequences of those behaviors or reinforcement. In this context, it may look like the mentor is facilitating growth via encouragement and other feedback to support the mentee to adopt behaviors that achieve beneficial milestones like a strong GPA, retention to graduation, or promotion and tenure while avoiding detrimental consequences.

Cognitivist. Driscoll (2000) emphasizes information processing and memory, or recall and reflection on past experiences to determine current and future learning processes and outcomes; it may look like shared reflection to help the mentee modify their engagement to achieve their own best potential.

Constructivist. Baker and Lattuca (2010) state that the context of the mentoring relationship is a crucial element and facilitator of mentees’ engagement and success. Knowledge is accumulated through experience with people and processes in the learning environment, and mentees construct meaning of those experiences through reflection to reconstruct new knowledge. It may look like mentors encouraging critical reflection upon achievements and failures to construct new knowledge and awareness of their growing identities.

Action Learning. According to Mullen (2000), action learning is experiential in nature; learning occurs in the doing and mentor-guided mutual reflection. It may look like mentor-supported shared actions and reflections or supported exploration in the professional environment via internships or volunteer work followed by debriefing, analysis, and planning for future engagement.

Transformative Learning. Mezirow and Taylor (2009) imply actively examining beliefs and values to arrive at one’s own understanding. It may look like mutual brainstorming of ideas and analysis of learning situations to develop new visions of the mentee’s identity and engagement in the academic world.

Mentoring as a Developmental Process

This section will discuss life stage theories, mentoring phases for career support, developmental stages, social theories, and organizational theories; citations are included on the reference page for a deeper investigation of each. Developmental theories approach mentoring by understanding that mentors and mentees are at different life stages as they progress through their educational and professional careers. Developmental theories may guide program directors to consider the phases and processes of mentoring relationships most relevant to their goals.

Life Stage Theory. Levinson’s (1978) life stage theory states that careers progress through periods of stability and decision-making and then transitional periods where individuals make changes to established commitments and beliefs. Mentors may be seen as models of identity, guides on a career journey, or sponsors of career success, while mentees are more receptive to and observant of their mentors, embracing relevant behaviors and attitudes. Outcomes may include achieving key milestones of academic progress as mentees develop a sense of identification with the mentor and belonging to the institution or discipline. Mentoring may include structured learning plans for achieving short-term goals while approaching the mentee’s big career dream or opportunities to observe the mentor in key aspirational roles.

Career Support Theory. Kram (1985) identified four progressive phases of the mentoring relationship: initiation, cultivation, separation, and redefinition. Mentors take flexible and evolving roles as both their and their mentees’ needs change while mentees are still seen as attentive to the mentoring they receive for each stage of their growth. It may look like orientation for new students in the initiation phase, moving to greater depth in the cultivation phase, where the most learning and development occur via career and psychosocial support functions for mentees to achieve their goals of academic success. Finally, separation indicates that the relationship as it was structured has come to an end, but it may continue to evolve through redefinition as both partners adopt new, more reciprocal roles. In this later phase, it may become a friendly social or collaborative relationship as each assumes new roles in their institution or discipline. Throughout this model, a structured learning or career development plan may guide each phase, identifying developmental milestones and career progression.

Developmental Stages Theory. According to Kegan (1982), mentors and mentees actively engage and construct reality within the environment in periods of stability and change, similar to Levinson’s (1978) life stage theory. Mentees progress from initial stages of dependence maturing through independence into mutual interdependence with their mentors. Confirmation of growth and development and sometimes contradiction of that growth are seen to progress in a continuous manner. This model offers the most mutuality of the three developmental theories as both the mentor’s and mentee’s roles will vary depending upon their own developmental stages. Your mentoring program may also be more mutual, adopting co-directed, self-directed, or institutionally derived learning plans.

Social Theory. If your program adopts one of the social theories, you will likely support faculty and peer mentors as role models of academic success in your discipline or program. You support mentors in introducing their mentees to members of their communities. You may pay special attention to how mentees develop crucial cultural capital in the forms of key academic and professional skills and social capital that will build their professional networks and enable them to succeed academically and later (Ahn, 2010). Or you may wish to ensure that mentors and mentees are engaged in mentoring relationships that provide for exchanges of social network contacts and the associated powers that accrue to successful participants (Scandura & Schriesheim, 1994). If this sounds like your program, then you may adopt one or more of these approaches: socialization, cultural/social capital, social exchange, and/or leader-member exchange.

Organizational Theory. Gottfredson and Mosher (2011) explain that if your mentoring program embraces a lens of organizational learning, you have likely designed processes and developmental milestones that support faculty, staff, and students to engage with and succeed at their individual and institutional goals. For example, you may establish protocols for providing reinforcement and feedback to mentors and mentees on their progress and achievements that move them and your program forward. As a director, you may pay special attention to demographic and generational shifts within your program, celebrating the presence of experienced faculty as you welcome the new contributions and perspectives junior faculty and students bring.

Types of Frameworks to Consider for Mentoring Programs

For this section, we have divided and grouped the frameworks into two manageable categories and suggested, in bold, authors and dates for your further research. Once you have considered which category your program best fits into, you can move to the next section, in which we offer a more detailed explanation of frameworks and a discussion of how those may be blended and customized to meet the needs of your unique program.

Theoretical Frameworks of Mentoring Programs Designed for Career Support

This first category discusses mentoring via career support theories, including foundational mentoring functions (Kram, 1985) and career choice (Theobald & Mitchell, 2002; Holland, 1996). If your program has a career support focus, these functions and decision-making processes may help mentors and mentees to achieve key individual and programmatic milestones, such as required GPA or project completion.

Programs for Career Development Functions

Kram (1985). Sponsorship promotes growth opportunities for the mentee by helping a mentee join a research team that would show them in a positive light to community members and leaders. Protection helps shield mentees from unwanted attention and assignments by advising them to take on manageable loads until they are better situated to launch their scholarly careers. Finally, coaching provides guidance on developing professional skills and navigating institutions and disciplines. It may mean helping a mentee prepare to present a low-stakes local brown-bag talk before an academic conference or suggesting they tackle more rigorous academic work to enhance their progress.

Programs for Career/Vocational Choice Models

Holland (1996). Holland proposed a career choice model grounded in six key personal orientations that may inform your mentoring program theory. If you apply Holland’s model, you support mentoring relationships that are realistic, investigative, artistic, social, enterprising, or conventional (RIASEC). As a director, you may pay special attention to matching mentors and mentees with complementary orientations and approaches to their scholarship and student development.

Theobald and Mitchell (2002). Theobald and Mitchell proposed a model that incorporates elements of career and psychosocial development functions with a master-novice element of social networks to foster students’ skills and knowledge growth. If you adopt this model for your program, you also attend to mentoring as socialization into career and organizational values and practices. Your model helps mentors and mentees to set individual learning goals that map onto larger institutional or programmatic goals. And you provide mentors with the necessary systemic scaffolds to achieve both of those goals.

Theoretical Frameworks of Mentoring Programs Designed for Supporting Developmental Process

This category of frameworks works well if your program embraces and supports the idea that mentoring occurs within broader communities and networks and that it need not be exclusively dyadic and hierarchical; you may be adopting a developmental network or communities of practice framework. Networking as a practice provides mentees access to the mentor’s professional network of internal and external colleagues. Networks are further defined in Chapter 27 and highlighted in the Chapter 28 case study. Mentees in these models are encouraged to work with, learn from, and model themselves upon various mentors and developers connected to their discipline, program, and institution. While there is great complementarity and even some overlap among these theories, we highlight important distinctions.

Programs for Social Network Support

Blancero and DelCampo (2005), Higgins and Kram (2001). Supported by the work of Blancero and DelCampo (2005) and Higgins and Kram (2001), social network programs support a broad constellation of mentors and developers in a developmental network with the mentee as the hub. Programs designed with a developmental or social network theory provide interactions within established social and academic networks and across network boundaries to foster newer contacts that benefit mentors, mentees, and the institution.

Programs for Social and Developmental Support

Borgatti and Halgin (2011). Social and developmental networks may also include personal developers, such as friends and family who support a new college student with important psychological support or employers who help a student balance work and school to support their aspirations (Hager et al., 2019). Having such a rich and diverse network helps mentees experience greater social integration and institutional commitment, which, for students, may lead to enhanced retention to graduation.

Programs for Communities of Practice Support

Dominguez and Hager (2013) commented that communities of practice act as “nodes of information exchange,” in which all community members develop greater mutuality and expertise to enact the practices of the community. This theory derived from Lave and Wenger’s (1991) research and builds upon the knowledge within the developmental networks research. A diversified network of multiple mentors provides opportunities for greater depth of socialization as mentees may see more aspects of their identities having legitimate roles in the practices of the community. In addition, it recognizes the legitimate expertise that entering student mentees bring to the community and helps them find a place to share that knowledge while they gain from other members. Finally, it also supports collegial, peer-to-peer mentoring across the network, inviting colleagues to contribute to the shared enterprises of higher education and student development.

Discussion: Connecting Theory to Practice

Arriving at this point in the chapter, you have examined many different yet complementary theories of mentoring and developmental relationships. The broad theoretical frameworks we covered include mentoring as a psychosocial support system, learning partnership, career support, and developmental network models. Now that you have read the chapter and reflected on our big questions, we hope our discussion has helped you identify those key theoretical frameworks that exemplify your current or proposed mentoring program.

Considering your emerging theory of mentoring, we will provide some additional ideas for how some of the frameworks might look in action. Remember, these recommendations are general, and you will want to adapt them as best suits the theories you have identified along with your institutional and programmatic context to achieve your program’s goals.

Mentoring as a Psychosocial Support System

Applying a theory of psychosocial support to your mentoring program helps program directors and participants focus their mentoring engagement around key developmental roles that support mentees in their growth.

Role Modeling

Program directors and mentors could help identify aspirational strangers or community partners on whom the mentees wish to model their success. Mentors should strive to model the norms, behaviors, and attitudes that demonstrate success in their field. Mentees may identify their own best set of role models in their networks and the broader field.

Counseling

Program directors who incorporate counseling into their models may see mentors as friendly and accepting sounding boards for mentees to express their interests and doubts, while directors ensure mentors and mentees are aware of institutional resources for mental well-being concerns.

Acceptance and Confirmation

Program directors can provide welcoming language and activities in their programming model. This psychosocial support may be an especially important element of your programs for marginalized or underrepresented students to help them see their identities represented and feel accepted and confirmed in the academy or the program/institution. Mentors who are members of underrepresented communities may find that students gravitate to them for their shared experiences, providing valuable support to students.

Friendship

If your program adopts a networked approach, you may guide both mentors and mentees to establish and appreciate appropriate boundaries of friendly advising versus friendship. Reminding mentees to establish friendships with a variety of community members and to nurture their personal networks helps them create a rich developmental network. Program directors, mentors, and mentees may also wish to consider friendship as a longer-term aspiration as their relationships progress from collegial but hierarchical to greater reciprocity and mutuality.

Social Integration

Orientation activities to both the program and the institution can provide students opportunities to integrate with like-minded peers. Directors may encourage mentors to develop their own pedagogical skills to capitalize on collaborative learning inside and outside the classroom to encourage peer-to-peer cooperation and integration. Programs engaged with social integration benefit from collaboration with other academic and student affairs offices, such as Student Affairs and Mental Health Services. Mentors may provide opportunities for groups of students to collaborate on shared projects and congregate in shared academic and social spaces; celebrating students’ shared engagement and accomplishments may serve as a reinforcement for those behaviors, further encouraging them to engage and ultimately persist.

Mentoring as Learning Partnership

Program directors who frame their programs with one or more of the learning theories we discussed are likely to see mentoring as a facilitated relationship where they and their programming support self-directed learning and experiences that achieve the mentees’ goals. Grounded in theories of adult learning, mentees take an active role in crafting and negotiating their learning goals and experiences. Learning in partnership models helps promote autonomy and self-confidence as mentees approach and achieve their independently or collaboratively designed learning goals, often with the reinforcement of their mentors and communities.

Behaviorist

Program directors who embrace a behaviorist theory reinforce achievements to encourage more behaviors and activities that lead to success. Cultural practices like public recognition can reward mentors and mentees when they achieve key developmental milestones or program successes. Mentors may reward mentees for large achievements like successful completion of a big project or incremental achievements like attending a tutoring session for writing or oral presentations.

Cognitivist

Program directors can design program materials or activities that encourage mentors and mentees to reflect upon their current levels of understanding and achievements along with struggles toward new goals to help them process their learning and plan for future achievements. Mentors should be aware of mentees’ prior knowledge, strengths, and challenges, to build upon that structure and scaffold their growth. Mentees can take the initiative to create their own reflection and analysis process that may include progress to desired outcomes and recognition of where and with whom they are experiencing their greatest learning opportunities and where they may be struggling.

Constructivist

Program directors are aware of the strong role their program’s context plays in supporting mentees’ learning; directors help mentors and mentees to see that constructing learning takes place over time. Mentors create opportunities for mentees to explore their emerging academic identities and express their creativity as they reflect upon what they have learned thus far to create new objectives and construct their identities.

Action Learning. Program directors may establish activities that mentors and mentees ought to accomplish to support active learning by doing. For example, program activities may scaffold scholarly writing and public speaking through authentic practices like community brown-bag lectures or ensuring that mentors invite mentees to give lectures and lessons in their classes.

Transformative Learning. Program directors with this theoretical framework shape their program to support mentees’ transformation of ideas, prior knowledge, and frames of reference via opportunities for innovation and reflection on their learning and the changes it can bring. Mentors may introduce challenges for mentees to analyze and resolve; mentees can engage in diverse networks of communities of practice to approach diverse challenges in their broader communities. Mentees are supported to be active learners, open to transforming, rather than relying solely upon prior knowledge. Mentees learn to embrace the new challenges their mentors and programs introduce as they critically engage their environments to build, expand and transform their frames of reference.

Mentoring With Developmental Theories

Like learning theories, developmental theories acknowledge that learning and growth occur across time and social contexts. Depending upon your approach, you may encourage cyclical passages from stability to more dynamic and transitional periods or a more sequential path across stages.

Levinson’s Life Stage Theory

Program directors who adopt Levinson’s theory of adult development acknowledge that adults move through periods of stability where mentors and mentees make life choices and commitments and then transitional periods where people change commitments as they reevaluate beliefs about themselves, their careers, and their relationships. Your program model may invite mentees and mentors to reflect on how their relationships have changed or are changing as both grow into their newer identities. Mentors working within this framework support mentees to know that transitions are a natural part of professional life and model how to engage the transitional periods. Mentees will gain valuable perspectives on necessary transitions from mentors and program directors who help them envision their mentoring relationships as evolving and developmental for both parties.

Kram’s Mentoring Phases

Program directors can build their program philosophy and activities around the phases of initiation, cultivation, separation, and redefinition. For example, program directors and mentors may actively engage in orientation activities that situate the relationship as supporting both program and professional goals. In addition, program directors, mentors, and mentees who attend to the separation and redefinition phases acknowledge that mentoring relationships evolve, and the relatively short timeframe of undergraduate or graduate studies requires them to plan for these transitions. Directors may establish activities or rituals that mark developmental transitions, and separation may be celebrated as mentees establish their own independent identities.

Kegan’s Developmental Stages

Program directors and mentors provide structures and experiences for mentees to move through key stages. Early dependence upon their mentors may suit new students, but greater independence occurs as they develop their skills and construct their academic identities; mutuality and interdependence arise as mentees take on greater responsibilities for their academic work and career trajectories. Mentors may establish activities like annual check-ins that help identify how mentees are gradually acquiring more sophisticated skillsets they can use with greater independence, ultimately taking a collegial or even leadership role within the work of the community as they redefine their roles and identities. Mentors are encouraged to have frank conversations about mentees’ entering skills and developmental needs; mentors and mentees may then create developmental learning plans incorporating signals that mentees are preparing to take on greater responsibility. This may require mentors to identify where they are comfortable handing over the reins and responsibilities to the mentee and how the mentee should demonstrate their own readiness.

Mentoring With Social Theories

Socialization

Program directors provide self-directed, co-directed, and mentor/program-directed learning plans as they socialize mentees into the community. Pay special attention to the context of your program to ensure you have a good mix of professional and social mentors and role models for your community of mentees. Program directors may need to “mentor the mentors” to be those role models, especially when they may not share key identity elements with their mentees. Mentors may share their earliest approaches to academic success by seeking tutoring and study skills, competencies some first-generation students have acknowledged would benefit their performance while contributing to greater social integration as they strengthen their academic skills.

Cultural/Social Capital

Program directors who wish to help mentees develop cultural capital ensure there are opportunities to develop key skills that facilitate their participation and success in their studies and careers. Attending to social capital implies you designed your program to help participants access social networks and the opportunities they may bring. Mentors in this model leverage their skills and cultural capital to help mentees develop theirs as their mentors introduce them to vital social networks and grow their social capital. Mentors may introduce student mentees to key academic or professional associates and associations to generate social capital and networks as they also model cultural skills necessary to engage those networks.

Social Exchange

Reciprocity appears in these relationships as mentors and mentees approach the relationships to gain skills or access cultural and social capital; contexts that support mutual benefits may have elements of social exchange. In this context, your program recognizes that such relationships may anticipate trade-offs or exchanges of time or resources that each is willing to make to achieve individual or programmatic goals; mentors have valuable cultural and social capital in their expertise and professional networks, while mentees bring the enthusiasm of novice practitioners, willing to make new connections. Directors ensure that participants have clear goals and that each can bring something to that exchange.

Leader-Member Exchange

Mentors may provide their mentees access to their networks in exchange for contributing their skills to achieving individual and community goals. Mentees may feel empowered to seek multiple models of academic practices and identities if your program design provides for it. This may look like mentors and mentees identifying their shared goals for the relationship and then assessing how the mentor can bring the relevant individuals and skillsets to support the mentee’s development while also maintaining or enhancing the mentor’s own institutional and disciplinary power.

Mentoring With Organizational Learning Theories

Organizational Learning Supports

Under this model, your program helps mentees “learn the ropes” of the institution and discipline (Dawley et al., 2008; Thompson, 2016). Your program provides clear individual and big-picture institutional and program-level learning goals, and you and your leadership team have articulated processes to achieve them. As a result, mentors and mentees know what goals are expected, how to achieve them, and how they contribute to your program as they contribute to individual learning and development.

Reverse Mentoring

As a program director, you are acutely aware of the great knowledge bases your faculty mentors bring to their disciplines, research, and pedagogy. You also embrace the idea that students can bring key knowledge, skills, and experiences into the community that more senior members may not have been aware they needed (Chaudhuri & Ghosh, 2012). Cutting-edge methods and ever-increasingly diverse life experiences expand our scientific perspectives as they enrich our scholarly communities.

Mentoring With Career Support Theories

Career Development Functions

Holland (1958) proposed that people choose careers in line with their preferred orientations, so program directors may align their activities with his RIASEC model to promote activities that capitalize upon those orientations in mentors and mentees (Holland, 1996; Theobald & Mitchell, 2002). Kram (1985) provides program directors with rich material for moving from theory to practice in programs designed around career support theoretical frameworks. These include the following.

Sponsorship. Program leadership can provide structural support for faculty to sponsor their mentees in opportunities that highlight their skills and contributions, helping them stand out in the community, especially if you tag them on professional social media. Students who identify as members of marginalized or vulnerable groups may benefit from sponsorship if they lack the social and cultural capital to engage with higher education or access these networks strategically. Your sponsorship shows them and others that they belong in higher education and your community.

Protection. Program directors can provide systemic guidance to help mentors shelter mentees from activities detrimental to their growth. Clear guidelines on program goals for mentors and mentees ensure that mentees engage in activities most likely to help them achieve milestones on their academic paths, such as appropriate GPAs and milestone projects. Conversely, directors and mentors may discourage mentees from taking on too many activities, diluting their attention, and slowing their mastery of skillsets needed in their academic community.

Coaching. Program directors can guide coaching practices that enact your mentoring theory and are relevant to the individual, program, and institutional goals. For example, if your program has established activities that help mentees and mentors achieve key milestones, you can guide mentors to coaching behaviors that are equally focused.

Challenge. As a program director, you may incorporate systemic challenges to encourage mentors and mentees to reach for higher achievements. Mentors are often best positioned to guide mentees to take on greater challenges by taking a more demanding class or applying for a “reach” fellowship. If their relationship exists within a developmental network or communities of practice model, the mentee may actively seek challenges within and beyond the main mentoring relationship.

Connecting Program Theory to Research

Our next section addresses programmatic assessment and research and asks program directors and leadership to identify how their theoretical frameworks can be used to understand the processes and outcomes of their theories in practice. Your program model may include ongoing institutional research and assessment cycles to measure achievements and plan for future growth; accreditation bodies and funders may require you to report an analysis of program outcomes. You may be interested in communicating your findings to other communities of scholars and practitioners. Professional meetings like the American Educational Research Association or the University of New Mexico Mentoring Institute can provide venues for you to contribute to and update the body of knowledge on mentoring programs. Sharing research from your theoretical frameworks may encourage others to do the same as they learn from your experiences and analyses and vice versa.

Using the Reflective Questions to Continue the Process Into Research

Research and writing can be demanding tasks in addition to managing your program while guiding mentors and mentees, so we encourage you to consider ways to “double dip” your research with your program assessment activities. This may help you join these translational research conversations sharing your analysis and reflections. Returning to our big reflective questions will help you identify relevant measures and programmatic research you wish to conduct.

Here we frame each big question as an assessment tool to help start your own brainstorming. This section is intentionally broad, introducing language across the mentoring theories we have discussed, so you may tailor your own assessments and research to the models you have adopted and adapted. To help you get started, consider these two steps to apply to each reflective question and the more minor questions or examples based on mentoring theories: (a) Start with your theory, then (b) state your research or practice goals associated with each big question. For example:

Why

Why do we mentor the way we do? Why did you select particular theories to frame your program goals and activities? How do your chosen theories help you achieve your goals?

Our mentoring theory is grounded in a learning partnership model of action learning. It helps us achieve our goals of helping students develop practical workplace skills as they participate in their mentors’ research/creative activities and in the community engagement element of our institutional mission. We measure this with student performance data in “real world” activities and settings such as internships.

If larger institutional goals or systems drive your program and theory, your statement might look like this:

Our mentoring theory is based on a psychosocial support systems model because our institution is committed to providing clearly articulated support for students to establish strong social integration and connections with their academic communities to help them achieve their academic and career goals. This model allows us to focus on and measure engagement with key mentoring functions to achieve our goals of students’ social integration.

Who

Who participates in and benefits from our mentoring initiatives or activities? Who is our target audience? Context may matter here as well; if your institution has established focal audiences such as first-generation or transfer students for mentoring support, you may be guided by these larger institutional objectives; such goals may also indicate the availability of systemic support and resources. A sample statement could sound like this:

Our mentoring program applies a developmental networks model as it serves the entire undergraduate population of our institution. We provide students many opportunities to identify, meet, and join different academic, professional, and social networks over their undergraduate careers. One measure of our success is students’ personal nominations of the faculty, staff, and student communities they engage. We also monitor how many students participate and from which programs, to ensure our program outreach connects with the broadest audiences.

Where

Where do we situate mentoring in our local institutional context, and how do resources, opportunities, and constraints in our context inform our programming model? What elements of the program or institutional structures shape your mentoring program? A sample statement:

Our social network theoretical framework of mentoring is based on legitimate peripheral participation by our mentees in communities of practice that include their mentors and other faculty and students. Our mentoring program is sponsored by the Office of Student Success, an interdepartmental student resource. We enjoy the support and oversight of the VP of Student Affairs and VP of Academic Affairs to provide mentoring programs that apply our theory as they support the institutional mission and vision. To recognize and measure the important contributions that mentoring makes to faculty and student success, our sponsors have secured funding for faculty release time to ensure they can engage with their mentees in formal program activities, informal meetings, and collaboration. Our assessment includes reports of those formal and informal activities and evidence of collaboration that demonstrate mentees’ moving from a peripheral role in their mentors’ communities to greater participation and independence within those communities.

What

What are our program goals, objectives, and outcomes? How do you translate your theoretical framework into measurable process and product outcomes? For example:

Our program embraces the theory of career support. Our career goals include sponsorship of mentees to new opportunities, provision of challenging opportunities to expand their skill sets, and coaching by their mentors to achieve those challenges and be secure in their public sponsorship. We measure those outcomes with evidence of public or private sponsorship of new opportunities, evidence of increasing challenges undertaken by mentees, and directed learning plans that demonstrate coaching by their mentors. Our long-term measures include first destination employment and graduate programs that alumni report.

What outcomes will help you measure benefits to mentees and mentors to show program success? What are your metrics of success to determine that your process and product outcomes have achieved your goals? Another sample:

Our mentoring theory applies behaviorist elements of reinforcement to encourage mentees to adopt key behaviors and reward them when they do, to achieve their—and our—goals. With that model in mind, we measure success as 80% of our first-generation, first-year undergraduate mentees will participate in a mutually agreed-upon number of academic support activities and achieve a GPA of 2.0 or better in their first year of college.

How

How does our program accomplish its goals? First, consider context in how you form your goals. Then, look at how your activities enact your theory and support your program’s goals. A sample statement:

Our transformative learning theory of mentoring means our program staff and mentors ensure that mentees engage in challenging and meaningful activities that contribute to the work of their mentors’ communities while pushing mentees to think critically about the scholarly community and their roles in it. To measure these outcomes, we gather documentary evidence of how our mentors increase the challenges they pose to their mentees and the mentees’ performance of increasingly sophisticated work; we also require mentees to write reflections on the growing challenges they are undertaking and how they shape their participation in their communities.

When

When is your timeframe for our programming? Long-term developmental relationships? Short-term initiatives and interventions? For example:

Our mentoring program is a multi-year model designed to support entering graduate students from historically marginalized communities to join and engage with the academic communities of their mentors. Our organizing developmental network framework for this mentoring program relies upon diverse communities of practice to help entering students engage with multiple university communities to develop the necessary cultural and social capital for successful participation in those professional networks. To assess the contributions of our model to student success, we have devised a series of survey and interview prompts as students complete each year; the prompts ask students to reflect upon the many individuals they are meeting, collaborating with, and learning from (quantitative reports on who works with whom and how) and how those relationships are contributing to their own academic engagement (qualitative reflections).

Future Research Considerations

Now that you are thinking of how you can apply your theoretical frameworks to understanding and analyzing your program’s achievements and we have suggested that you disseminate your findings as research-informed practice, we want to turn to promising directions for future research in the field of mentoring within higher education settings. For this section, we apply a more macro lens of future research, and once again propose examining intersections of complementary theoretical areas—psychosocial support systems, learning partnerships, career and developmental network theories—rather than focusing on singular theoretical frameworks.

We propose that future research analyze the contributions of using a framework like the big reflective questions to establishing a mentoring program identity. This chapter has highlighted how numerous theories can integrate and complement each other. We propose that researchers examine program-level outcomes of mentoring models appropriating elements across the different theoretical frameworks. Our approach of reflecting on big questions to craft a unique program identity may help program designers do just that as they adopt an integrated model and examine its processes and outcomes.

Theories in the mentoring field were once built upon homogeneous populations of individuals in industry and corporate America. However, faculty mentors and student mentees now make up a much more diverse and complex world of higher education. Future research should continue to examine how these theories do or do not help us support the experiences of individuals historically and culturally underrepresented in higher education.

Throughout this chapter, we have encouraged you as program directors, mentors, and mentees to create activities and scaffolds to support mentoring relationships and mentor/mentee success. Future research should continue to elaborate on the outcomes we seek and those we achieve through our mentoring programs. Higher education and mentoring researchers have identified many quantitative metrics and milestones of achievement where mentoring can make a difference. We propose that future research apply a mixed methods approach to more fully examine and understand the experiences of directors, mentors, and mentees. Doing so will elevate the science of mentoring research as it better elucidates the outcomes and nuanced processes inherent to successful mentoring programs from those three perspectives.

We encourage program directors to participate in translational research conversations and to join research communities to inform and shape the mentoring field. Future research should capitalize on this new community of scholar-practitioners to examine how your theoretically informed practices translate to program outcomes to contribute to the growing body of evidence-based practice and research.

Our chapter concludes with the promise of networking models of mentoring, such as developmental networks and communities of practice, and a challenge to reframe our mentoring models with greater mutuality and reciprocity. Future research should continue to examine the contributions of participation in numerous and varied communities to mentor and mentee success and engagement (Hager & Weitlauf, 2017; Baker et al., 2013). As directors and faculty mentors, we may neglect the contributions of personal communities to supporting student success (Hager et al., 2019). Given the increased diversity present in higher education (Clutterbuck et al., 2012), it is reasonable to hypothesize that a diversely populated community will provide numerous role models of identities and opportunities for acceptance and confirmation of individuals’ experiences. Consider how social network analysis can demonstrate the contributions of communities of practice to marginalized scholars (Buchwald & Dick, 2011).

Conclusion

We hope this chapter has provided you, program directors, supporters, and participants with the tools necessary to design or reverse-engineer your program’s guiding identity and the theoretical frameworks that can inform and shape your activities, engagement, and assessment. Our reflective questions are tools you may return to routinely to assess how you maintain alignment with your identity or how your program identity may evolve with time and reflection. Cycles of reflection, a theme you noticed in many of our theoretical frameworks, may also inform how you engage with your own theories of mentoring. Your institutional context may change so that a program of traditional dyadic relationships has new access to networks and communities. To capitalize on networking possibilities, you may wish to adopt more elements of developmental networks and communities of practice as you adopt more organizational learning goals in line with institutional shifts. We encourage you to embrace this dynamic and evolving approach as you refine your program identity and theories to design activities that achieve your goals. One of the most expansive and optimistic elements of program design, and often the place designers start, is program activities. We hope our approach helps you design theory-based programming to engage mentors and mentees and support them in their academic journeys.

Grounding your goals, programming, and outcomes in research-based theories can also guide your program assessment. Once your programming is up and running, you will be able to frame assessment metrics that map to your identity and the theories that enact it. For example, if your program uses key developmental milestones to demonstrate success, you can track mentees’ achievements like GPA, retention, transition to candidacy, and completion. If your goals are for psychosocial support, you may measure how the provision of key support functions like acceptance and confirmation contribute to mentees’ feelings of social integration and examine their persistence. Your internal assessment will likely have an external audience with funders and supporters within your institution or beyond. From these assessments, sharing your findings with the broader community of mentoring researchers and practitioners is a short, hopefully more approachable, goal.

At this point in the chapter, we bring a bold challenge to program designers: As you craft unique localized mentoring models that capture your program identity, share those with other researchers and practitioners. We propose moving our mentoring models from traditional transactional and hierarchical approaches to embracing greater mutuality among mentors, mentees, and other developers in your communities. This paradigm shift capitalizes on generational demographic changes as our current and future faculty and students are more engaged with collaborative work and learning than in prior generations (Chaudhuri & Ghosh, 2012). The shift invites program designers to embrace the collaboration and reciprocal development inherent in social and developmental network theories and communities of practice while it integrates roles, functions, and practices across the spectrum of mentoring theories. Thus, we have the opportunity to appropriate and extend elements of more transactional mentoring theories into realms of greater reciprocity as we move our field into a more transformational approach.

With a transformational and reciprocal mentoring theory, your relationships and their overarching goals could be housed more expansively within the resources of the broader community instead of within individual dyads. This may help participants and programs establish relationships with the potential for far-reaching scientific and creative collaboration.

References

Ahn, J. (2010). The role of social network locations in the college access mentoring of urban youth. Education and Urban Society, 42(7), 839–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124510379825

Baker, V. L., & Lattuca, L. R. (2010). Developmental networks and learning: Toward an interdisciplinary perspective on identity development during doctoral study. Studies in Higher Education, 35(7), 807–827. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903501887

Baker, V. L., Pifer, M. J., & Flemion, B. (2013). Process challenges and learning-based interactions in stage 2 of doctoral education: Implications from two applied social science fields. The Journal of Higher Education, 84(4), 449–476. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2013.11777298

Blancero, D. M., & DelCampo, R. G. (2005). Hispanics in the workplace: Experiences with mentoring and networking. Employment Relations Today, 32(2), 31–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/ert.20061

Borgatti, S. P., & Halgin, D. S. (2011). On network theory. Organization Science, 22(5), 1168– 1181. https://doi-org.dist.lib.usu.edu/10.1287/orsc.1100.0641

Buchwald, D., & Dick, R. W. (2011). Weaving the native web: Using social network analysis to demonstrate the value of a minority career development program. Academic Medicine, 86(6), 778–786. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318217e824

Chaudhuri, S., & Ghosh, R. (2012). Reverse mentoring: A social exchange tool for keeping the boomers engaged and millennials committed. Human Resource Development Review, 11(1), 55–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484311417562

Crisp, G., & Cruz, I. (2009). Mentoring college students: A critical review of the literature between 1990 and 2007. Research in Higher Education, 50(6), 525–545. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-009-9130-2

Clutterbuck, D., Poulsen, K., & Kochan, F. (2012). Developing successful diversity mentoring programmes: An international casebook. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

Dawley, D. D., Andrews, M. C., & Bucklew, N. S. (2008). Mentoring, supervisor support, and perceived organizational support: What matters most? Leadership & Organization Development Journal, 29(3), 235–247. https://doi.org/10.1108/01437730810861290

Dominguez, N., & Hager, M. (2013). Mentoring frameworks: Synthesis and critique. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-03-2013-0014

Driscoll, M. P. (2000). Psychology of learning for instruction. Allyn & Bacon.

Gottfredson, C., & Mosher, B. (2011). Innovative performance support: Strategies and practices for learning in the workflow. McGraw Hill Professional.

Hager, M. J., Turner, F., & Dellande, S. (2019). Academic and social integration: Psychosocial support and the role of developmental networks in the DBA. Studies in Continuing Education: Professional Doctorate Curriculum, Pedagogy, and Achievements, 41(2), 241–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/0158037X.2018.1551202

Hager, M. J., & Weitlauf, J. (2017). How can developmental networks change our view of work-life harmony? The Chronicle of Mentoring and Coaching, 1(Special Issue 10), 894–899.

Higgins, M. C. & Kram, K. E. (2001). Reconceptualizing mentoring at work: A developmental network perspective. Academy of Management Review, 26(2), 264-288.

Holland, J. L. (1996). Exploring careers with a typology: What we have learned and some new directions. American Psychologist, 51(4), 397.

Kegan, R. (1982), The evolving self: Problem and process in human development. Harvard University Press.

Knowles, M. S., Holton III, E. F., & Swanson, R. A. (2014). The adult learner: The definitive classic in adult education and human resource development. Routledge.

Kolb, D. A. (2014). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. FT Press.

Kram, K. (1985). Mentoring at work: Developmental relationships in organizational life. Scott Foresman.

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

Levinson, D. (1978). The seasons of a man’s life. Random House.

Lunsford, L., Baker, V., & Pifer, M. (2018). Faculty mentoring faculty: Career stages, relationship quality, and job satisfaction. International Journal of Mentoring and Coaching in Education, 7(2), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMCE-08-2017-0055

Mezirow, J., & Taylor, E. (2009). Transformative learning in practice: Insights from community, workplace, and higher education. Jossey-Bass.

Mullen, C. A. (2000). Constructing co-mentoring partnerships: Walkways we must travel. Theory Into Practice, 39(1), 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip3901_2

Mullen, C. A., Fish, V. L., & Hutinger, J. L. (2010). Mentoring doctoral students through scholastic engagement: Adult learning principles in action. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 34(2), 179–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098771003695452

Ogunyemi, D., Solnik, M. J., Alexander, C., Fong, A., & Azziz, R. (2010). Promoting residents’ professional development and academic productivity using a structured faculty mentoring program. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 22(2), 93–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401331003656413

Peel, D. (2005). The significance of behavioural learning theory to the development of effective coaching practice. International Journal of Evidence-Based Coaching and Mentoring, 3(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.24384/IJEBCM/3/1

Roche, G. R. (1979, January). Much ado about mentors. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/1979/01/much-ado-about-mentors

Scandura, T. A., & Schriesheim, C. A. (1994). Leader-member exchange and supervisor career mentoring as complementary constructs in leadership research. Academy of Management Journal, 37, 1588–1602.

Theobald, K., & Mitchell, M. (2002). Mentoring: Improving transition to practice. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 20(1), 27–33.

Thompson, K. S. (2016). Organizational learning support preferences of millennials. New Horizons in Adult Education and Human Resource Development, 28(4), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/nha3.20158

Tinto, V. (2012). Leaving college: Rethinking the causes and cures of student attrition. University of Chicago Press.

Appendix

Mentoring Program Continuous Implementation Cycle