Checking In

Learner Perceptions of the Value of Language Study in College

Julian Ledford and Tijá Odoms

Abstract

An understanding of the products that Generation Z students value the most from their college-level language study is essential for instructors who must effectively unpack second language theories within the context of their classroom instruction. This preliminary study examines the value system regarding language study as revealed in the language-learning perceptions of a group of current language learners (n = 53) and recent college graduates (n = 49) at a small, private, liberal arts college in the southeast. Through qualitative analysis of student responses, the following emerged as language-learning products that students valued the most: (a) practical application of a specific language to vocational activities and to everyday life, (b) representation of and engagement with the cultures of the people whose languages (L2) they study, and (c) engagement with speech communities in which the second language (L2) is spoken with varying levels of proficiency. The study concludes with suggestions for areas of further study that will be of value to second language researchers and instructors alike.

Keywords: generation Z students, language-learner engagement, perceptions of learners, perceived importance of language

Introduction

Student perceptions of college-level study are in high demand as colleges prepare to navigate purported demographic shifts, namely an overall decrease in college-aged Generation Z students and an increase in Hispanic collegegoers beginning in 2026 (Grawe, 2018a; Campion, 2020). College administrators and language departments alike are relying heavily on student perceptions to restructure many aspects of their operational systems in hopes of attaining desired enrollment and providing a learning environment that supports today’s students. Within the discipline of language study, reports on student perceptions aren’t new. As Tse (2000) noted, between 1973 and 2000, roughly, researchers carried out many investigations on the opinions and dispositions of language students regarding several aspects of the language-learning environment (p. 69). Today, the opinions of students regarding the effectiveness of their language instruction are constantly requested. What is less common in second language literature are studies pertaining to student perceptions of the overall importance of language study at the college level. To be clear, this preliminary study does not ask whether language study is an essential part of postsecondary education. Rather, through qualitative analysis of student responses to an online survey, the study seeks to ascertain the aspects of language study that today’s students perceive as being the most important. We believe that this knowledge will be beneficial in many ways as it will: (1) reveal students’ knowledge and perceptions of language learning; (2) provide researchers with new vocabulary with which to rewrite the contextualizing frameworks of established language theories; (3) reveal areas in which various interventions might take place to optimize students’ engagement with and appreciation of not only language learning but of all aspects of their academic pursuits, and (4) provide a useful context to facilitate the move from the theoretical—second language theories— to the practical—pedagogical approaches.

Background

Troublesome times

Generations of language teacher-scholars who completed their undergraduate or graduate degrees in the almost eight decades after the end of the Second World War have undoubtedly heard rumors about the survival of language studies programs within secondary and postsecondary curricula. For recent language teacher-scholars, it would seem as if crisis preparedness and militant second language advocacy were informal, built-in aspects of their training. Brown, Caruso, Arvidsson, & Forsberg-Lundell (2019), considering the attribution of the word crisis to language studies as pessimistic and alarmist, noted the beginnings of crisis discourse in the March 1942 paper delivered by American educator Isaac Leon Kandel at the Foreign Languages Teachers’ Conference in New York (p. 41). The paper, entitled “Study of Foreign Languages in the Present Crisis,” though delivered during the throes of the Second World War, focused instead on another ongoing war waged between traditional disciplines that focused on their own interests rather than engaging students in a course of study that “transcend[ed] preparation for immediate use” (Kandel 16). The war of “mentalities” (23) regarding language instruction and its outcomes for Kandel was the substance of the crisis within the study of foreign languages at that time. Since then, as Brown, Caruso, Arvidsson, & Forsberg-Lundell (2019) noted, the nature of the crisis has changed. We note, however, that the feeling of language studies’ demise at the hands of an antagonistic other still exists.

This feeling of impending doom felt within language studies is understood within the wider context of crisis within the humanities. Schmidt (2018), listing language studies as one of the four major humanities fields, noted a decline in majors within humanities-related disciplines between 2010 and 2017. Additionally, he noted that this decline within liberal arts colleges, where all disciplines are purportedly kept in a certain equilibrium, is even more dramatic. Though Schmidt attributed this decline in humanities majors to, among other things, an increased interest in science-focused fields and disciplines that provided practical training related to vocational goals, Agudo (2020) would seem to attribute the decline, with specific regard to language studies majors, to inequalities in administrative treatment. Describing language departments as “the poor relative on campuses,” Agudo (2020) noted that language departments are traditionally under-resourced and face a greater volume of inequalities when compared to other disciplines. While a causal relationship between declining numbers in language studies majors and in administrative support for language departments is difficult to substantiate, the feeling of demise among language teacher-scholars is validated.

Irrespective of the empirical and theoretical contributors to the negative disposition of the language study collective, it is true that the field of second language studies has undergone several interrogations to not only guarantee its survival but to better serve the interests of learners. Among these lines of inquiry is an introspective look at internal tensions within language studies itself and how they impact language learners. For one, the use of the term foreign as an epistemological determiner for language studies is one of Osborn’s (2000) concerns. Osborn, who attributes the failure of language education in the U.S. to sociological rather than methodological issues (p. 8), argues that the ideological goal of language learning as expressed as the requirement to experience foreignness foists the hegemonic view of the elite minority upon all learners (pp. 11-12). Added to Osborn’s discussion of the word foreign is Agudo’s (2021) argument relating to the same word. For him, not only is the term reflective of a pedagogical agenda that is devoid of cultural framing but of pedagogical approaches that are best “meaningless” and, at worst, “harmful.” For Agudo (2021), and ostensibly for Osborn, the harm inflicted by the word foreign stems from the thought processes used to conceptualize what is not foreign. By that, as Agudo (2021) explained, the ideology that constructs the foreign/non-foreign binary is often rooted in simplistic, essentialist worldviews that make false assumptions about the learners present in the classroom. Thus, Kandel’s (1942) description of warring ideologies is imperfectly recreated here. Whereas Kandel’s argument concerned institutional and national culture surrounding the goals of language learning in secondary and postsecondary education, Osborn’s (2000) and Agudo’s (2021) arguments focused on the role of culture in repositioning second language education within frameworks of diversity, equity, and inclusion.

The triumvirate ideological structure conjured by the terms diversity, equity, and inclusion can also be seen as one of the guiding principles behind the World-Readiness Standards created by the American Council on the Teaching of Foreign Languages (ACTFL): Communication, Cultures, Connections, Comparisons, and Communities (National Standards Collaborative Board, 2015). And the beneficiaries of this framing are two-fold: language learners and language study. The latter beneficiary, described previously by scholars as having a tenuous existence in education and under threat from more robust disciplines, is now conceived as a lifelong academic experience that provides cognitive enhancement applicable to all disciplines and vocational pursuits. The Connections standard, positing that learners “connect with other disciplines and acquire information and diverse perspectives in order to use the language to function in academic and career related situations” (National Standards Collaborative Board, 2015), thus recalls and diffuses the tension presented in Kandel’s (1942) use of the term études désintéressées, defined as “studies which are valuable irrespective of time and place and therefore available resources when special occasions arise” (p. 23) to describe language studies. By that, the notion of preparing ways for students to become lifelong users and learners of language, regardless of the practical, day-to-day use of said language (L2) in their vocation, is central to the world-readiness standard. So important is this ideal that scholars, such as Simonsen (2020), argue for more deliberate restructuring of language curriculums to fulfill the Connections standard more clearly. Focusing on career-readiness and the requisite and complementary expertise and areas of knowledge within the healthcare system and business-related fields, for example, Simonsen would seem to see benefit in forging ties with disciplines that, for Schmidt (2018) and Agudo (2020), were considered inimical to the survival of college language-study programs. By these World-Readiness Standards, the goals of language learning and instruction have centered on empowering language learners to respectfully describe, investigate, and reflect critically upon the philosophical objects related to the people whose language they are learning to speak (L2) and those that animate their own lives. As such, the World-Readiness Standards purports to dismantle notions of language studies as being in an antagonistic relationship with itself and with other disciplines by harmoniously tethering language studies to the core and to all the resultant constructs of the academy. Thus positioned, any attack on language study should be seen as an attack on the academy itself.

Notwithstanding language studies’ attempts to rebrand and reposition itself within the foundation of secondary and postsecondary education, in recent years, American colleges have eliminated or reduced foreign language programs. Johnson (2019), for one, reports that colleges closed 651 language programs between 2013 and 2016. Johnson (2019), like Schmidt (2018), also reports that cuts in language programs are consistent with declining enrollment in language classes during the same period. And as Bauman (2020) reports, it stands to good reason that the 2019 pandemic will provoke some college administrators to take additional drastic measures to secure the fiscal solvency of their institutions and, consequently, guarantee uninterrupted employment for language teacher-scholars. The trouble in humanities, and specifically in language studies, therefore seems to have taken on a new dimension, the yet-untenable nature of which extends beyond the scope of this article. That significant changes have taken place in language studies since Kandel’s paper in 1942, and the quelling of the 2019 pandemic is a given. To be sure, though, the nature of things dictates that paradigm shifts present a complex system of dialogistic parts that conspire to provoke arrhythmic and aleatory change. Incidentally, as university systems contemplate their financial books, they are also preparing to fully meet the needs of a new generation of students.

Perception Discourse

This preliminary study on student perceptions of second language learning aligns itself loosely with previous work done on the subject, though not much has been published on students’ perceptions of the importance of language studies. Tse’s (2000) study sought to ascertain students’ perceptions of their foreign language study through qualitative analysis of student autobiographies. Grounding her work in Gardner’s (1985) socioeducational theoretical frameworks and research on affective filters of second language acquisition forwarded by Horowitz, Horowitz, & Cope (1986), Krashen (1981), MacIntyre (1995), and Young (1991), Tse (2000) did not seek to ascertain learner perceptions of the importance of language studies rather learner perceptions of instructional methods notions of language learner success and failure. Similarly, Tapfenhart’s (2011) work on learner perceptions contributed to second language learning motivation discourse by investigating student perceptions of instructional practices. More recently, two studies on student perceptions contribute more pointedly to this current study. The first, Thompson, Eodice, & Tran (2015) focused on student opinions of general education requirements. Agreeing with Reardon, Lenz, Sampson, Johnston, & Kramer (1990), Thompson, Eodice, & Tran (2015) stated that student voices were often underrepresented in matters regarding general education reform (p. 279). In the second study, de Saint-Léger & McGregor (2015) investigated student perceptions of pedagogical practices related to intercultural, transcultural, and translingual competencies. In more recent years, besides work done on student opinions of the instructor and their bearing on language learner motivation (Drakulić, 2019), additional research relating to learner perceptions of established (Menke & Anderson, 2019) and emergent (Crane & Sosulski, 2020) pedagogical approaches within second language teaching and learning has been published.

This preliminary study thus attempts to understand the perceptions of the importance of second language learning among Generation Z students at a small liberal arts college that has a language requirement. By ascertaining student perceptions of overall importance of language studies in their undergraduate career and in their post-graduation lives, we seek to validate and challenge prevailing knowledge relative to today’s postsecondary language learner and identify useful areas of inquiry as teacher-scholars continue to move from theory to practice.

The Study

This study sought to gain insight into the perceptions of current students (CURR) and recent graduates (ALUM) concerning the importance of language study within the composite experiences of their long undergraduate career. The term composite experiences grounds itself in flourishing discourse proposed by Keyes (2002) and Keyes (2007) that focuses on achieving branches on emotional, psychological, and social wellbeing to preserve and promote mental health. The term long undergraduate career borrows from historians who refuse the primacy of chronology as the determiner of the start and end points of phenomena, preferring instead to focus on key contributive and resultant occurrences relative to an established epicenter. Correspondingly, rather than a focus on the period between matriculation and graduation, the long undergraduate career would also include discussions of high-school and post-graduation experiences that have an impact on college experiences expected, imagined, actualized, and remembered. For our purposes, we sought to focus on how Generation Z students valorize language study within the complex network of dialoguing forces that determine their undergraduate lives. A reflection on students’ opinions of college-level language study will help teacher-scholars to not only recalibrate recently established theoretical frameworks but also unpack them using terminology and references that speak to the students that populate their language classes. Ultimately, student retention, success, and providing instructors with tools that foster efficient engagement with essential information are aspirational goals. For now, however, the following questions were addressed in this preliminary study:

- What are student perceptions of the value of their language study?

- What are student perceptions of the value of cross-cultural understanding?

- What changes do students believe should be made to language study?

Methodology

Participants

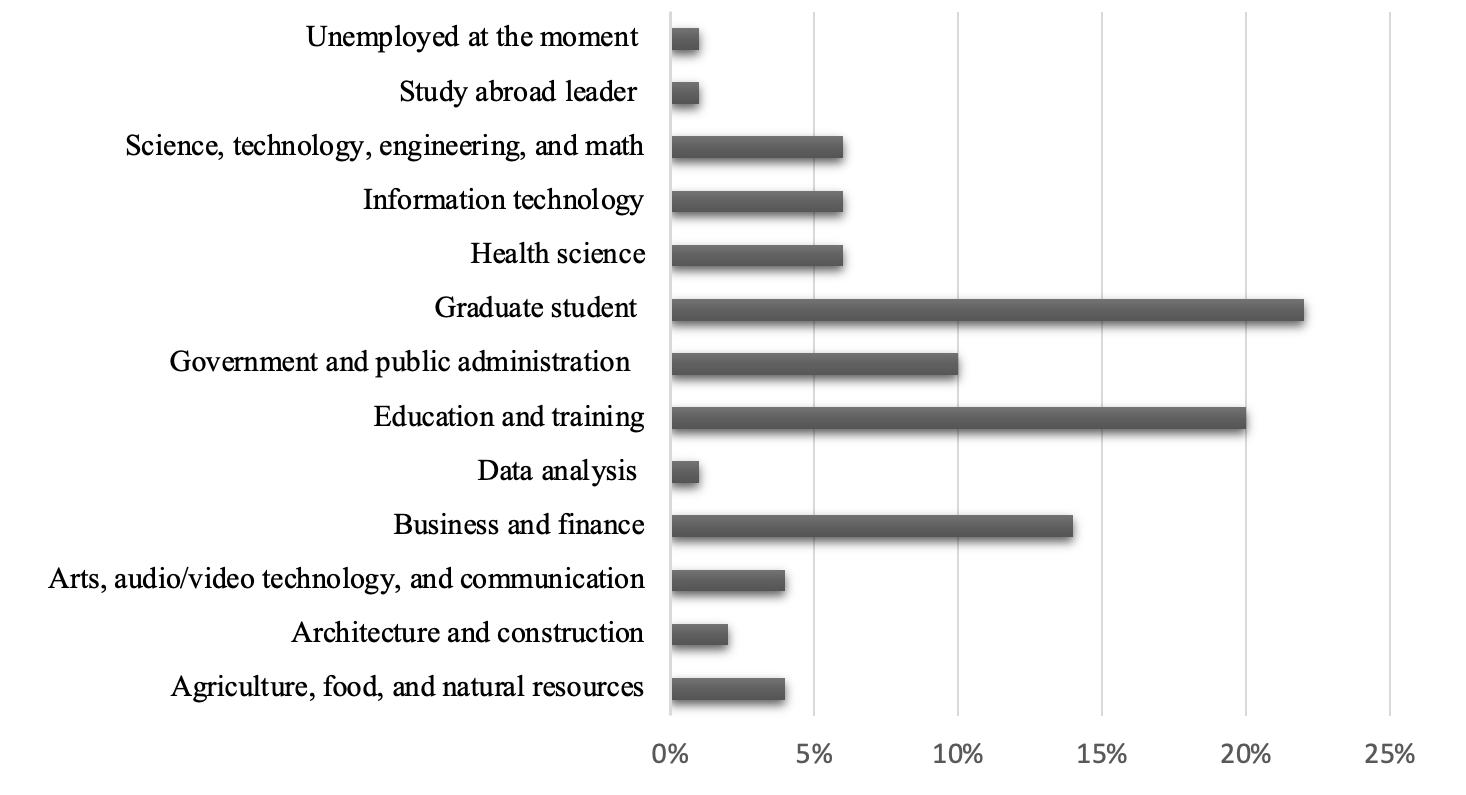

In spring 2021, between April 29 and June 16, undergraduate students currently enrolled in classes at the Institution and students who graduated from the same Institution between May 2016 and May 2020 received an email invitation to participate in an Institutional Review Board-approved study by completing an online survey. Of note, the Institution was a small, private liberal arts college whose general education curriculum required that most students complete a sequence of language study within at least one language. Typically, students who chose to study a language for the first time at the Institution devoted approximately four semesters to this endeavor. However, students who had studied language formally in high school sat a placement exam and, depending on their placement, completed their language sequence in fewer semesters. From the student responses gathered, we only considered those from current students who had taken at least one language class at the Institution (n = 53) or recent graduates (n = 49) who took at least one language class at the Institution. Regarding the occupation of the recent graduates, 1% (1) were unemployed, 22% (10) were in graduate school, and 77% (38) were employed (as shown in Figure 1). Among the current undergraduate students, approximately 25% (13) were first-year students, 28% (15) were sophomores, 26% (14) were juniors, and 21% (11) were seniors.

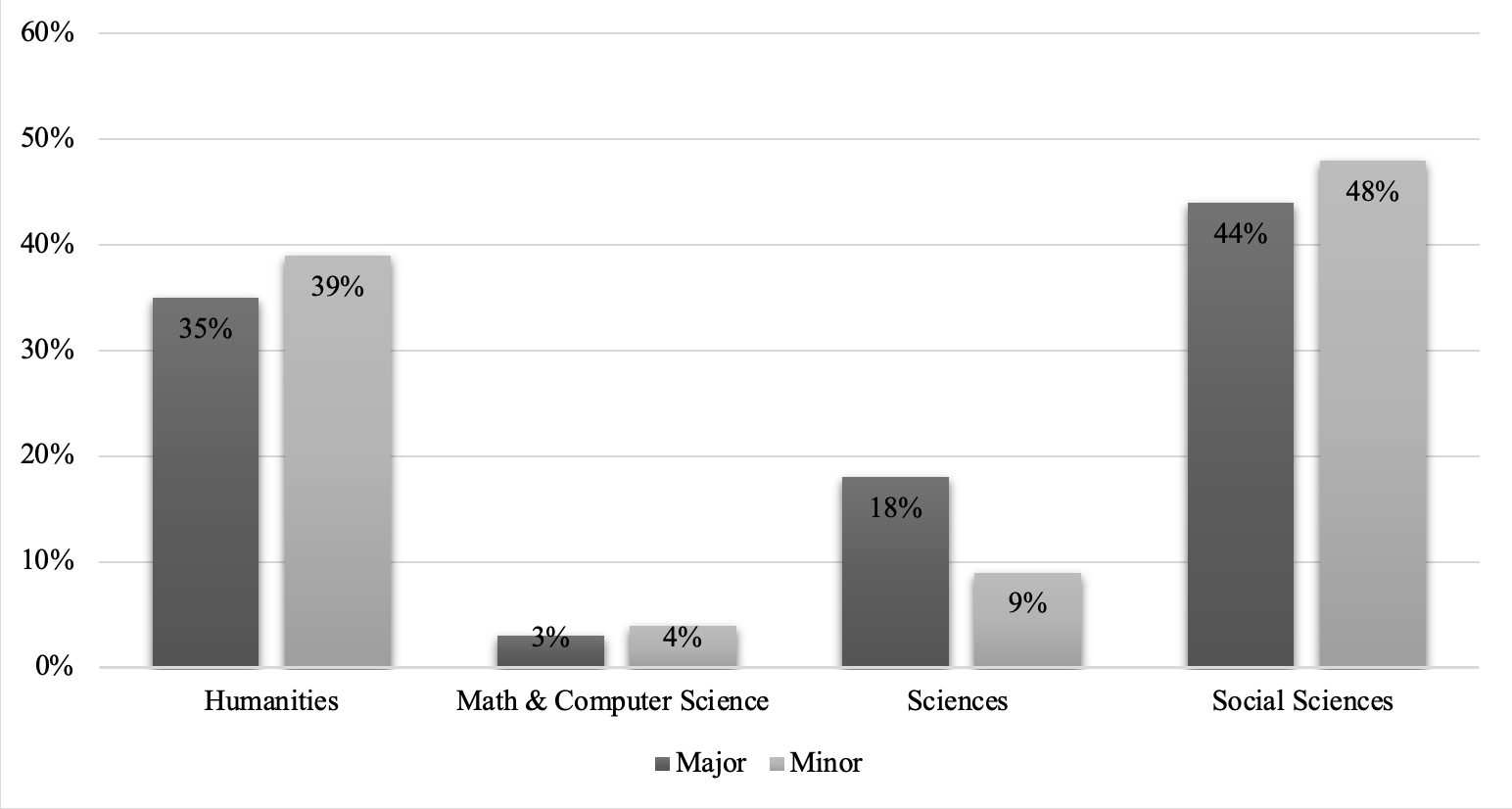

Among both sets of participants, approximately 61% (62) expressed that they were very familiar with the general education requirements, 31% (32) stated that they were moderately familiar, and approximately 8% (4) stated that they were only slightly or not at all familiar with the general education requirements. With specific regard to the general education requirement relating to language study, approximately 92% (94) were aware that their language study contributed to the completion of one of their general education requirements. Only 8% (8) were unaware of this fact. For undergraduate students who had already completed the language requirement, approximately 57% (25) took additional classes in language study and 43% (44) did not. Among recent graduates, 65% took additional language classes post-completion of language requirements and 35% did not. Finally, as shown in Figure 2, the subject pool represented major and minor areas of study in four broadly conceived disciplines. Regarding participants who had already decided to pursue specializations in the humanities, 34% (44) had majors in language study and 70% (33) had minors. From this subject pool, it was determined that both sets of participants had sufficient knowledge of and experience with language study at the Institution, thus validating their empirical evidence. Additionally, the spread of major and minor areas of specialization avoided biases caused by the overrepresentation of any one discipline. It should be noted, though, that there were significantly fewer responses from students in disciplines housed in math, computer science, and science. Finally, among recent graduates, the diverse career sectors represented created a more veritable and balanced depiction of career destinations post-graduation.

Data Collection

Correspondents in the College of the Dean of the College sent an email to the general student body containing a link to the consent form and the online survey. Correspondents in the Office of Alumni Relations sent the same to a curated listserv of recent graduates. Neither current students nor recent alums were engaged in prior discussions pertaining to the topic of the study. Instead, the email they received briefly mentioned the general focus of the study: students’ perceptions of their language-learning experiences in college. Willing participants were then asked to follow the included link in the email to complete a 15-minute, anonymous, electronic survey. Once within the survey, participants read the consent form and acknowledged their willingness to participate in the study. Participants were also informed that they could abandon the survey at any point if they no longer wished to participate.

The survey prepared for current students contained four sections. In the first section, participants answered questions related to their class standing, semesters of study at the Institution, major and minor areas of specialization, languages spoken at home, languages studied in high school, and language study already completed in college. In the second section, participants answered questions about their understanding of language study and its connection to the Institution’s general education curriculum. The third section contained questions about participants’ personal experiences with and perceptions of language study in college. The final section provided space for participants to reflect generally on their language study and provide constructive feedback for the Institution.

The survey prepared for recent graduates also contained four sections. Though this survey was similar to the one just described before, it was also modified significantly. In the first section, recent graduates reported their graduation year, major and minor areas of specialization, languages spoken at home, and language studied in high school. In the second section, similar to the germane section in the survey for current students, recent graduates were asked questions pertaining to their understanding of the Institution’s general education curriculum and its relation to language study. In the third section, beyond soliciting information on personal experiences with language study while in college, recent alums were asked to speak about the same in the context of their current vocational or non-vocational activities after graduation. The final section provided space for recent alums to reflect generally on their language study and provide constructive feedback. In both versions of the survey, the final question also allowed participants to address any aspect of their language-learning experience that may not have been addressed in other survey questions.

From the pointed survey questions and the free-write section at the end, researchers were able to collect several pieces of data. For the purpose of this current study, the questions that follow yielded the most pertinent responses relative to the research questions listed previously.

- You are having lunch with a prospective student who asks you to explain what cross-cultural comprehension means to you. What would you say?

- Which three words would you use to describe your language learning experience at [the Institution]?

- Beyond helping you to complete your general education requirements, do/did you see any additional benefit to your language studies? Please explain your answer.

- If the Institution didn’t have a language learning requirement, would you still have chosen to study a language? Please explain your answer.

- In terms of your curricular experience at [the Institution], how important are/were your language studies? Please explain your answer.

- Reflecting on your experiences in language studies, is there any constructive feedback that you could offer? Please write your feedback below.

Additionally, from the survey prepared for recent graduates, the following question was particularly useful:

- In your current occupation, do you find that your language study proved to be beneficial. Please explain your answer.

Analyses

Though survey responses lent themselves to both quantitative and qualitative exploitation, the latter process was primarily used in this study. Following the sequencing suggested by Strauss & Corbin (1990), open coding was used to assign general descriptors to student responses to the seven questions listed before. Once satisfied with these general, lower-level categories, the process was repeated to create more specific categories. Next, the process of axial coding (Strauss & Corbin, 1990) was employed to organize the categories into specific and inter-related themes from which the thesis for the study was derived.

Results

Based on the results of qualitative analysis, student responses fell into three categories, moving from the empirical to the abstract: (a) perceptions of the value of language study in the context of composite undergraduate experiences, (b) perceptions of the value of cross-cultural understanding in the context of composite undergraduate experiences, and (c) perceptions of institutional changes that would enhance language study at the Institution. Though it is true that the three categories share significant commonality, this classification allows for iterative and nuanced readings of student responses that contributed to a deeper understanding of what students think.

Perceptions of the Value of Language study

When asked to choose three words to describe their language study in college, the vast majority of student responses fell into the following categories: (a) emotions (n = 154), classroom experiences (n = 65); content (n = 38); and benefit (n = 28). Regarding the largest category, emotions, words used such as boring, exhausting, exciting, fun, good, humiliating, inspiring, and stressful reflect the memory of how students felt and were made to feel in a language class. Regarding classroom experiences, students used words such as immersive, thorough, comprehensive, virtual, repetitive, reading, and hands-on to speak about aspects of the learning environment. Next, regarding content, students reflected on the information they received and engaged within language classes, using words such as expansive, Eurocentric, elitist, cultural, artsy, analytical, insightful, important, eye-opening, and informative. Finally, the following words reflected that there was or should be a benefit from having studied a language in college: rewarding, enriching, worthwhile, valuable, fulfilling, unhelpful, unfulfilling, helpful, fruitful, and beneficial. Surprisingly, only two responses to this question reflected words explicitly linked to the language requirement (requirement, required).

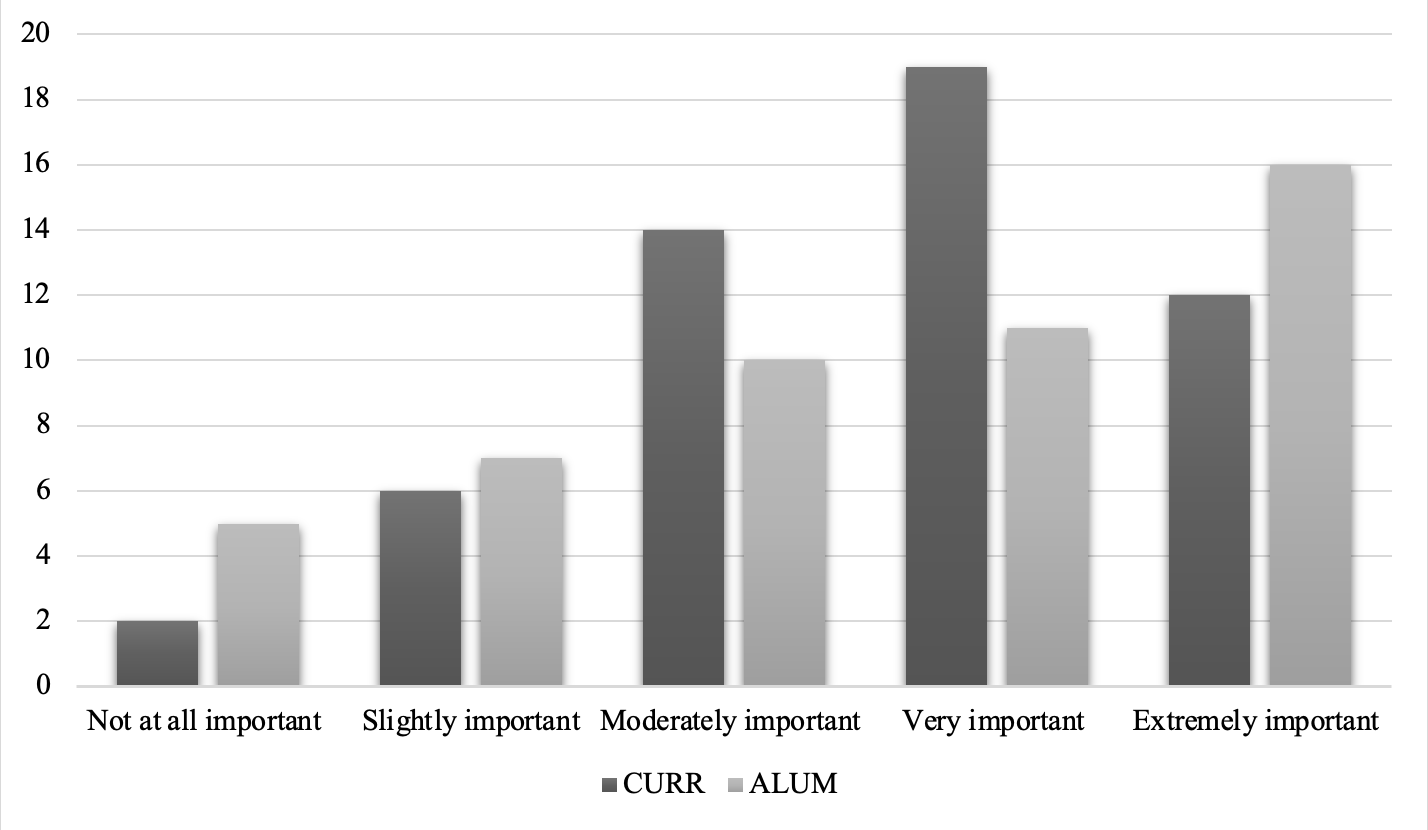

Requirements (n = 37) featured more prominently, however, when participants were asked about the importance of language study within their curricular experience. Besides requirements, the importance of language study was related to emotions (n = 37), knowledge and understanding of other cultures (n = 12), personal fulfillment as a college student (n = 16), cognitive development (n = 11), reward-based on time investment (n = 9), practical application (n = 8), and community building (n = 8). Overall, as shown in Figure 3, most participants (80%) ascribed at least moderate importance to language study within their curricular experience.

When asked if they thought there was additional benefit to their language study beyond fulfilling their language requirement to graduate, most students responded positively. Approximately 74% (39) of current students (CURR) and 86% (42) of recent graduates (ALUM) said that they perceived an additional benefit to their language studies. Only 2% (1) of CURR and 10% (5) of ALUM selected that they didn’t see additional benefit to their language study beyond the language requirement. When asked to expand on their reasons for attributing or not attributing additional value to their language studies, among those who responded positively, the vast majority perceived certain benefits that were coded as relating to their future or current careers (n = 23), cognitive development (n = 31), knowledge and understanding of other cultures (n = 28), community building (n = 23), cognitive application to other classes (n = 13), and study abroad (n = 13). Additional benefits, although fewer in number, included the feeling of positive emotions (n = 3) and practical applicability to everyday life (n = 5).

For the six students who did not perceive any additional benefit to their language learning, their reasons included general lack of interest and the belief that their language study was only beneficial in completing graduation requirements. One of these six students stated, “No, however now I do see the benefits of language study and regret not putting more into my studies” (ALUM 49).

Related to the expression of regret in the last response mentioned before, recent graduates were asked a follow-up question pertaining to the perceived benefit of language study in their current occupation. We found that 44.9% (22) of participants gave a positive response and 34.7% (17) gave a negative response. The remaining 20.4% (10) were unsure if their language study proved beneficial in their current occupation. Among reasons for positive and negative responses, practical application of language study was most prominent (68%). However, reasons relating to intercultural competency (13%) and community building (9%) were not as prominent. One student who did not perceive any benefit to their language study in their current occupation noted:

I obtained a master’s degree in [specific country where language is spoken], where my language skills were […] useful. I had difficulty obtaining a permanent job there afterward and returned to the US to pursue a hopeful medical career. Every day I encounter the use of [specific language] professionally, and I often wish that I had been more practical with my language learning choices rather than following my intellectual curiosity (Alum 24).

In analyzing these responses, it should be noted that student responses regarding the practical application of language study were mostly language-specific as opposed to metacognitive or metalinguistic.

The focus on specific languages was present when students were asked if they would have still chosen to study a language if language study wasn’t required by the Institution. Among current students, 52.8% (28) said yes, 18.9% (10) said no, and 28.3% (15) said maybe. Among recent graduates, 63.3% (31) said yes, 14.3% (7) said no, and 22.4% (11) said maybe. Of note are the reasons given by those who were undecided about whether they would have decided to study a language. Their reasons center on several factors: (a) time constraints relative to not only completion of other major areas of specialization but time invested relative to professional and personal reward gained, (b) belief in aptitude and confidence as a language learner, and (c) the offering of and/or the placement in a specific language.

Perceptions of the Value of Cross-Cultural Understanding

When asked to provide a working definition for the term cross-cultural comprehension, a term used by the Institution to summarize the category to which language study falls within the general education curriculum, only 3% (2) of current students and 4% (2) of recent graduates said that they would not be able to define the term at all or defined it solely as a series of courses needed to graduate. Most responses, however, revealed an impressive understanding of cross-cultural comprehension that included the following general notions: appreciating others, understanding others, communicating respectfully with others, empathizing with others, broadening horizons, building community, knowledge of the global community, knowledge of others, and understanding our own selves. While some responses were succinct: “Understanding and finding value in other cultures and how they relate to our own” (CURR 3), others were more verbose:

At its core, I believe it is taking the time to learn about, recognize, and appreciate similarities and differences among differing cultures. Comprehension implies a holistic understanding, which requires time and effort to explore the complexities of unique cultures. I believe that learning to embrace and celebrate diversity, both through empirical experience and formal classroom instruction, is fundamental to achieving cross-cultural comprehension (ALUM 8).

Regardless of the length of the responses, most students were able to demonstrate a base understanding of cross-cultural understanding in their own words.

Perception of Changes to Language study

The final section of the survey for both sets of participants asked for constructive feedback based on general reflection on language study at the Institution. Here, students were empowered to include information that they felt was important to them and information that was not housed elsewhere in the survey. Not surprisingly, some responses centered on changes to language placement and the language requirement itself:

I wish the requirement was only for a class. I stuck with a language that I studied in middle school and high school because that path led me to finishing the requirement in the most direct way. If I didn’t feel that I was taking away time from other courses I wanted to explore at [the Institution]. I would have loved to try a completely new language that wasn’t available to me in my prior years of schooling […] (ALUM 40).

However, most responses concerned a desire for more classes focused on the discovery of cultures where the target language is spoken as opposed to a focus on the exposure to grammatical structure:

A much stronger emphasis on the culture classes over the language classes, which actually teach foreign cultures and how they think about the world they live in, language classes do not do this at all; it’s possible and common even for students to take years’ worth of language classes and still know very little if anything about the culture and society to which that language belongs (CURR 8).

I think [the Institution] could apply the functional model of community engagement to the languages (CURR 37).

Along these same lines, some students mentioned the need to devote more of their language study to speaking and conversation:

I wish there was more opportunities to practice language orally. I feel like I’m prepared to read and write, but if I went to a country where my studied language is spoken, I think I’d have a lot of trouble communicating. (CURR 36)

Finally, students expressed the essential need for the Institution to diversify its language offerings and challenge the traditional primacy of Europe within language study: “A less [European-centered] curriculum. Less colonizers please! More on Latin America and the Caribbean. And Indigenous folks […]” (ALUM 17).

Though these responses do not reflect an understanding of the programmatic realities that affect the functioning of language departments at the Institution, these responses give an insight into what students perceive as essential within their language study. Additionally, the responses allow teacher-scholars to strengthen or rework existing theories relative to second language study and identify new areas of inquiry.

Discussion

Students’ perceptions of second language learning experiences at an institution that has a language requirement provided interesting insight into what students value the most about language study. Researchers can use this insight to inform future research on pedagogical practices that aim to present second language learning in a context that fully resonates with today’s students. With this in mind, based on their prominence in the students’ responses, the following emerge as continued areas of interest for second language instructors and researchers: (a) practical application of a specific language to vocational activities and to everyday life, (b) representation of and engagement with the global cultures of the people whose languages (L2) students study, and (c) engagement with speech communities in which the second language (L2) is spoken with varying levels of proficiency. We will elaborate on these areas in the order just presented.

Practical Application of Language Study

From student responses, the importance or lack of importance of language study is primarily attributed to students’ ability to use the language (L2) in practical ways in their vocational activities and in their daily lives. For current students and recent graduates, practicability in language study was mostly defined as opportunities to communicate orally with others who also speak the L2. With regard to recent graduates whose understanding of practicability included using L2 to complete vocational tasks, they also attributed great importance to using the language in their current employment. For most respondents, the fact that their current occupation did not require them to speak to clients in L2 rendered their language study of little value. It would seem, then, that the educational trends concerning the practical value of language study that vexed Kandel (1942) are in high demand among today’s students. Also, the participants in this study did not report great value in the educational experience that Kandel (1942) attributed to Dr. John Dewey, who countered the notion of value and use by privileging studies that “ought to be appreciated on their own account – just as an enjoyable experience, in short'” (p. 23). However, the Communication standard that strives for students to “communicate effectively in more than one language in order to function in a variety of situations and for multiple purposes” (National Standards Collaborative Board, 2015) comes closer to affirming the greatest importance of language study as perceived by language learners today. However, what is emerging from student responses is the speed with which they want to be able to speak the language. This notion also corresponds with Weber & Keim (2020), who summarize research on Generation Z students:

In particular, [researchers] suggested that Generation Z students have the urge to multitask, shorter attention spans, the drive for instant satisfaction, the desire for collaborative learning, a preference for professor-student interactions based on real relationships and learning that is practical and relevant to their future careers. (p. 10)

This notion of instant gratification is supported by students’ concern that the Institution required more than one semester’s worth of language study and that they perceived little reward for time they invested in language study. Though this concern is unique to this institution, it does ground itself in the idea that students desire to quickly see the benefit of their effort in practical ways.

From all of this, two conundrums arise that will require further study. First, research on second language acquisition informs us that formal classroom instruction, as opposed to study abroad programs or intensive immersion programs, is a less effective way of developing oral proficiency in the form of fluency (Freed, Segalowitz, & Dewey, 2004; Mora & Valls-Ferrer, 2012). Therefore, we see a generation of students who want to see quick progress and reward in an aspect of an academic discipline that has been proven to develop slower and less spectacularly. In other words, if students expect to experience significant gains in oral proficiency after a semester or even a year of formal instruction, their expectations will be unmet. Additionally, from responses given, students do not perceive the study of grammatical structures as a classroom experience that is essentially contributive to the development of their oral proficiency. Contrarily, several students expressed negative dispositions to this exercise and expressed more positive feelings to conversation. For these students, then, their experiences with formal classroom instruction are of little value. Furthermore, for those students who are unable to participate in study away language programs because of financial and programmatic obstacles, they may never experience the reward they had imagined receiving at the end of their language study. Second, seeing that it is unwise to pretend to perfectly predict the future, it is not sustainable practice to hinge the value of language study on the guarantee that the student will be required to speak the language (L2) regularly in their future career.

Engaging with Cultures

Speaking with others, as explained previously, is one practical product of language study that Generation Z learners value highly. Engaging with cultures where the language (L2) is spoken was also of great importance. Here, beyond communicating through speaking, the notion of engagement was seen in exposure to and an increased knowledge of different cultures with the aim of reflecting critically on one’s own subjectivities and proclivities. It stands to reason, then, that language study framed by Byram’s (1997) objectives pertaining to intercultural communicative competence and ACTFL’s Cultures standard (National Standards Collaborative Board, 2015) is appreciated highly by today’s learners.

We cannot ignore, however, two additional areas of concern related to students’ perceptions of language study and cultural engagement. First, students’ perceptions reveal the belief in a binary that creates an antagonistic relationship within itself: language study as learning grammar and vocabulary and language study as learning about other cultures. While language instructors understand the foundational role of grammar and vocabulary in developing language-learning competencies in traditional classroom settings, this understanding doesn’t seem to be clear to learners. Additionally, many respondents saw learning about other cultures as a sort of reprieve from learning structural components of the language (L2), even where cultural engagement was the purported goal. While this notion might not fully recall Kandel’s (1942) notion of the desire for a “painless education” (p. 12), continued research is needed to show how to negotiate difficulty, complexity, and forms of cognitive dissonance when learning a language through instruction in college. Future research on navigating cognitive dissonance relating to language study and today’s students might also lead to a reconsideration of the definition of the word academic. Second, some students considered the representation of culture within pedagogical materials to be hegemonic. As mentioned by some respondents, the focus on cultural objects belonging to European colonizers was highlighted as an aspect of language study to change. The fact that only five students mentioned this concern is extremely provocative. For some students, knowledge-based cultural engagement with a focus on European cultures is expected and valued highly. For others, this same approach to cultural engagement is seen as Eurocentric and an oppressive act of erasure that is ignorant of past and present atrocities. Contrarily, cultural engagement operationalized as community engagement with cultures belonging to territories outside of Europe may be seen as exploitative, patronizing, or even as an act of tokenism for some students. The point here is that language classrooms are populated by students whose perceptions of acceptable and fulfilling cultural engagement create a wide spectrum. To foster sustained investment in language study, future research will continue to explore ways of integrating cultural engagement into language learner identity discourse. In so doing, no member of the language-learning community should have negative dispositions toward the representation of culture in their classes. Ultimately, in support of research done on Generation Z students (Mohr & Mohr, 2017; Seemiller & Grace; 2017; Weber & Keim, 2021), this current study encourages further research on sustainable ways of adapting learning modalities to suit the needs of today’s students. As mentioned previously, operationalizing cultural engagement in the study of language is of great importance to this study’s participants.

Community Engagement

An additional form of desired engagement that emerged from this study was community engagement. Not only did respondents express a desire to speak with people in their immediate and extended residential area and those they met in their professional lives, one student suggested that language study should be reconceptualized using the frameworks of community engagement. These reports support the idea that the Communities standard that states that learners “communicate and interact with cultural competence in order to participate in multilingual communities at home and around the world” (National Standards Collaborative Board, 2015) is of extreme importance to students. Additionally, research that shows ways of reframing traditional pedagogical practices by a focus on community engagement, such as Randolph & Johnson (2017), will continue to be of great value to language instructors. Finally, a vast number of students expressed a desire to spend more time speaking with their classmates and their instructors in L2. Not only does this understanding support research about Generation Z learners and their desire to engage in more one-on-one interaction with instructors (Weber & Keim, 2021), but it also reminds us of an often-overlooked community: the classroom. From these responses, we are reminded that the language-learning classroom constitutes a multilingual community that students recognize, value highly, and in which they want to invest.

Conclusion

The qualitative analysis of responses on this preliminary study reveals that practicability, cultural engagement, and community engagement are products of language study that students value the most. As stated before, future research is needed to provide these language-learning products sustainably and ethically for today’s learners.

Regarding practicability, students defined this as becoming quickly proficient in L2 to be able to speak the language in their daily lives and at work. Both definitions present challenges for language study as they ignore the nature of how oral proficiency is acquired through formal instruction and present a reductive and unbalanced approach to the relationship between vocation and language study. To address these concerns, future research within language awareness (LA) will be beneficial in several ways. First, research on language awareness (LA), such as presented by Scott, Dessein, Ledford, & Joseph-Gabriel (2013), should be employed to mitigate the hyper-focus on practicability relative to speaking ability. By focusing instead on the cognitive, social, and psychological gains of language study, students will not only no longer hinge the value of their language study on speaking ability but may also begin to see language study as contributing to several areas of their overall wellbeing in college and beyond. It should be highlighted, too, that difficulty and hardship are not inherently inimical to wellbeing. Second, collaborative LA studies and career development studies on the benefit of language study on career exploration, mobility, and evolution will help students to see greater applicability of language study beyond college and equip language instructors with ways of creating a “contemporary approach to learning” (Mohr & Mohr, 2017; p. 90). Finally, LA studies that provide a transparent and honest view of the authentic speech acts that students will be able to complete after each semester of classroom instruction will help learners to adjust their expectations and allow instructors to structure their objectives and assessments accordingly.

Regarding cultural engagement, besides continued research that seeks to acknowledge and empower the plural identities of language learners, language instructors will benefit from additional research on learner identities and how they affect expectations of cultural engagement within language study. Furthermore, more pointed studies might provide language instructors on how to engage their students with ongoing discussions on the implications of colonialism, imperialism, and racism on the universality of certain languages and the diminishing or eradication of others. This discursive approach to cultural engagement within language study will help to remove affective filters that hinder the investment of certain language learners in their language study.

Finally, regarding community engagement, language instructors should feel empowered to invest great time in identifying, celebrating, and promoting the classroom as a multilingual community of which they are a cherished part. Continued research that focuses on critical reflection and ways in which language instructors develop their own identities in their classroom will therefore be of great value. Such a focus on community building with people whose lives make up a vast amount of the communicative content of language study might, in turn, redefine the word practical and satisfy the desire for acceptable cultural and community engagement. Language instructors might also be able to remind students that cultural engagement and community engagement, which they name as essential products of language study, also belong to the realm of the practical.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

Agudo, R. R. (2020, December 1). Reconsidering an often poor relative on campuses. Inside Higher Ed. Accessed 16 July 2021 at https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2020/12/01/reconsideration-value-language-learning-college-opinion

Agudo, R. R. (2021, April 7). Can we rid language departments of the f-word? Inside Higher Ed. Accessed 16 July 2021 at https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2021/04/07/academe-shouldnt-automatically-call-languages-other-english-foreign-opinion

Bauman, D. (2020, October 30). Can These Degree Programs, Under Assault for a Decade, Survive a Pandemic? The Chronicle of Higher Education. Accessed 16 July 2021 at https://www.chronicle.com/article/can-these-degree-programs-under-assault-for-a-decade-survive-a-pandemic

Brown, J., Caruso, M., Arvidsson, K., & Forsberg-Lundell, F. (2019). On ‘crisis’ and the pessimism of disciplinary discourse in foreign languages: An Australian perspective. Moderna språk, 113(2), 40-58. https://ojs.ub.gu.se/index.php/modernasprak/article/view/4363/3753

Byram, M. (1997). Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Philadelphia, PA: Multilingual Matters.

Campion, L.L. (2020). Leading through the enrollment cliff of 2026 (Part I). TechTrends 64, 542–544. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-020-00492-6

Crane, C., & Sosulski, M. J. (2020). Staging transformative learning across collegiate language curricula: Student perceptions of structured reflection for language learning. Foreign Language Annals, 53(1), 69–95. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12437

de Saint-Léger, D., & McGregor, A. (2015). From language and culture to language as culture: An exploratory study of university student perceptions of foreign-language pedagogical reform. The French Review, 88(4), 143-168. https://doi.org/10.1353/tfr.2015.0240

Drakulić, M. (2019). Exploring the relationship between students’ perceptions of the language teacher and the development of foreign language learning motivation. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 9(4), 364-370. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0904.02

Freed, B.F., Segalowitz, N., & Dewey, D.P. (2004). Context of learning and second language fluency in French. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 26, 275–301.

Gardner, R. C. (1985). Social psychology and second language learning: The role of attitudes and motivation. London: Edward Arnold.

Gardner, R. C., & Lambert, W. E. (1972). Attitudes and motivation in second language learning. Rowley, MA: Newbury House Publishers.

Grawe, N. (2018a). Demographics and demand for higher education. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press

Grawe, N. (2018b). Advancing the liberal arts in the face of demographic change. Liberal Education, 104(4), 6-11.

Grawe, N. (2021). The agile college: How institutions successfully navigate demographic changes. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Horowitz, E., Horowitz, M., & Cope, J. (1986). Foreign language classroom anxiety. Modern Language Journal, 70, 125-132.

Johnson, S. (2019, January 22). Colleges lose a ‘stunning’ 651 foreign-language programs in 3 years. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Accessed 16 July 2021 at https://www.chronicle.com/article/colleges-lose-a-stunning-651-foreign-language-programs-in-3-years/

Kandel, I. L. (1942). The study of foreign languages in the present crisis. The French Review, 16(1), 16-23. https://www.jstor.org/stable/381309

Keyes, C. L. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43(2), 207-222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Keyes, C. L. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62(2), 95-108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95

Krashen, S. (1981). Second language acquisition and second language learning. New York: Prentice Hall.

Levin, D. (2019, March 28). Generation Z: Who they are, in their own words. The New York Times. Accessed 16 July 2021 at https://www.nytimes.com/2019/03/28/us/gen-z-in-their-words.html

MacIntyre, P. (1995). How does anxiety affect second language learning? A reply to Sparks and Ganschow. Modern Language Review, 79, 90-99.

Menke, M. R., & Anderson, A. M. (2019). Student and faculty perceptions of writing in a foreign language studies major. Foreign Language Annals, 52(2), 388–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12396

Mohr, K., & Mohr, E. S. (2017). Understanding generation Z students to promote a contemporary learning environment. Journal on Empowering Teaching Excellence, 1(1), 84-94. https://doi.org/10.15142/T3M05T

Mora, J.C., & Valls-Ferrer, M. (2012). Oral fluency, accuracy, and complexity in formal instruction and study abroad learning contexts. TESOL Quarterly, 46, 610–641.

National Standards in Foreign Language Education Project. (2015). World-readiness standards for learning languages (4th ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

Osborn, T. A. (2000). Critical reflection and the foreign language classroom. In Henry A. Giroux, (Ed.), Critical Studies in Education and Culture Series. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Randolph L.J., Jr. & Johnson, S. M. (2017). Social justice in the classroom: A call to action. Dimension, 99-121.

Reardon, R. C., Lenz, J. G., Sampson, J. P., Jr., Johnston, J. S., Jr., & Kramer, G. L. (1990).

The “demand side” of general education—A review of the literature: Technical Report No. 11. Center for the Study of Technology in Counseling and Career Development. https://career.fsu.edu/sites/g/files/imported/storage/original/application/234658db2090e3f7c7dfaaa5159bf0c3.pdf

Scott, V., Dessein, E., Ledford, J., & Joseph-Gabriel, A. (2013). Language Awareness in the French Classroom. The French Review, 86(6), 1160-1172. Retrieved July 26, 2021, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/23511341

Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2017). Generation Z: Educating and engaging the next generation of students. About Campus, 22(3), 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/abc.21293

Simonsen, R. (2021). How to maximize language learners’ career readiness. Language Teaching, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444821000227

Strauss, A., & Corbin, J. (1990) Basic of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

Tepfenhart, K. (2011). Student Perceptions of Oral Participation in the Foreign Language Classroom. SUNY Oswego Dept. of Curriculum and Instruction. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED518852.pdf

Thompson, C.A., Eodice, M., & Tran, P. (2015). Student perceptions of general education requirements at a large public university: No surprises? The Journal of General Education, 64(4), 278-293. https://doi.org/10.1353/jge.2015.0025

Tse, L. (2000). Student perceptions of foreign language study: A qualitative analysis of foreign language autobiographies. The Modern Language Journal, 84: 69-84. https://doi.org/10.1111/0026-7902.00053

Weber, K. M., & Keim, H. (2021). Meeting the needs of generation Z college students through out-of-class interactions. About Campus, 26(2), 10–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1086482220971272

Young, D. (1991). Creating a low-anxiety classroom environment: What does language anxiety research suggest? Modern Language Journal, 75, 426-437.