Enhancing Technology-Based Distance Education Delivery Using Collaborative Team-Teaching Methods

Susan Cutler Egbert, Ph.D., LCSW and Sean Camp, LCSW

Abstract

Present pandemic-related circumstances have created unique challenges for educators and students alike. Information and communication technology (ICT) based team-teaching and collaborative course design can effectively mitigate feelings of isolation and disconnection and enhance student engagement within a remote education context. This article presents a theory-driven framework and “how-to’ practical strategies for utilizing team-teaching methodology through web-based delivery platforms. Content focuses on student participation and active learning, curriculum- and technology-related issues, and challenges inherent in synchronous web-based course delivery.

Keywords: team-teaching, distance education, coronavirus, web-broadcast

The exponential growth of internet access and information and communication technologies (ICTs) has increasingly influenced educational practices in the United States and worldwide (Perron et al., 2010). The global coronavirus pandemic necessitated abrupt and unprecedented engagement with ICTs by educators everywhere (Shoraevna et al., 2021). Suddenly, emergency remote teaching became not simply a “necessary evil” or rural-based paradigm but a required solution (Bozkurt & Sharma, 2020; Hodges et al., 2020).

University students and instructors often perceive technology-based distance learning as impersonal and isolating, a challenge we had previously addressed pedagogically and methodologically through the development of an ICT-delivered collaborative team-teaching approach (Camp & Egbert, 2018). This established framework served us well in responding to the unique context created by the pandemic, and we found it to be easily adaptable to the Zoom-based, virtual teaching environment.

Neither of us ever experienced team teaching as students. We were taught by solo professors and were mentored and trained to teach alone. In 2008, we both accepted faculty positions at Utah State University in a newly created statewide Master of Social Work program delivered primarily via interactive video conferencing (IVC). We were assigned to campuses miles apart from each other and our faculty colleagues. We were tasked with teaching courses in areas in which we felt strong—and areas in which we did not—and to deliver instruction alone to a scattered group of mostly commuter students who arrived after a full workday and were expected to sit through six hours of class every Tuesday night. Both of us had prior university teaching experience, but this new context presented a new and challenging “perfect storm” for potential disaster in terms of our ability to keep students (as well as ourselves) engaged, connected, and entertained. Thus, we embarked on a team-teaching journey motivated more by desperation than inspiration.

“I loved the team-teaching aspect. I was able to see clarification on items and see two different sides of a story; having two instructors brought greater perspective to the class.” – Student Course Evaluation comment

The field of social work is a practice-based profession, as well as an academic discipline. It is underpinned by theories from the social sciences, humanities, and cultural studies. Our profession engages people, communities, institutions, and organizations to assess and intervene in human challenges and social justice considerations. Facilitating student development of these professional competencies and necessary interpersonal interaction skills is the primary goal of social work education. From our perspective as professional social workers and professional educators, team teaching makes us better instructors and increases the impact we have in the classroom. Along with modeling collaboration and professionalism, team teaching in the distance education context reduces isolation, improves engagement, and mitigates technology-related anxiety for both students and faculty (Bettencourt & Weldon, 2011). These concepts are particularly relevant to social work and other human service-based disciplines and are equally important in any educational realm in which instruction is delivered remotely using ICTs.

Blanchard (2012) describes “the vision of an individual professor lecturing in front of a classroom full of attentive students [as] so iconic that it is hardly ever questioned. Such a vision is not only a product of our own experiences as students but is reinforced by popular media images of bearded, tweed-clad, white men that [sic] bombard our collective subconscious” (p.338). The gap between the “sage on the stage” and reality in distance education is both profound and pervasive. Team teaching has been recognized as an effective strategy to bridge this gap, and numerous researchers have noted significant advantages in team teaching as compared to courses taught by individual instructors, including:

- Effectively managing workloads with regard to course design and development, ongoing course management, and evaluation (Canaran & Mirici, 2020; Eisen & Tisdell, 2000; Harris & Harvey, 2000).

- Modeling professional collaboration and problem-solving (Eisen & Tidsell, 2000; Laughlin, Nelson, & Donaldson, 2011).

- Exposing students to differing points of view and areas of instructor expertise (McKenzie et al., 2020; Harris & Harvey, 2000; Pliner, Iuzzini, & Banks, 2011).

- Enhancing faculty development and increasing support for pedagogical decision-making (Pliner, Iuzzini, & Banks, 2011).

Researchers have also identified various models of team teaching relevant to distance learning (Collins, B.C., Hemmeter, M.L., Schuster, J.W. & Stevens, K.B., 1996), including:

- Lead and supplemental instructors model, with one instructor assuming responsibility and the supplemental instructor providing support and back-up.

- Multiple instructor model with each instructor assuming full responsibility for specific portions of the course.

- Guest lecturer model, utilizing a primary instructor along with supplemental guest speakers.

- Co-instructor model, with two instructors sharing all responsibilities for all aspects of the course.

We have used all four of these models in our approach to collaborative teaching and have landed on the Co-Instructor Model as the most impactful for students, as well as the most manageable and equitable with regard to instructor workload.

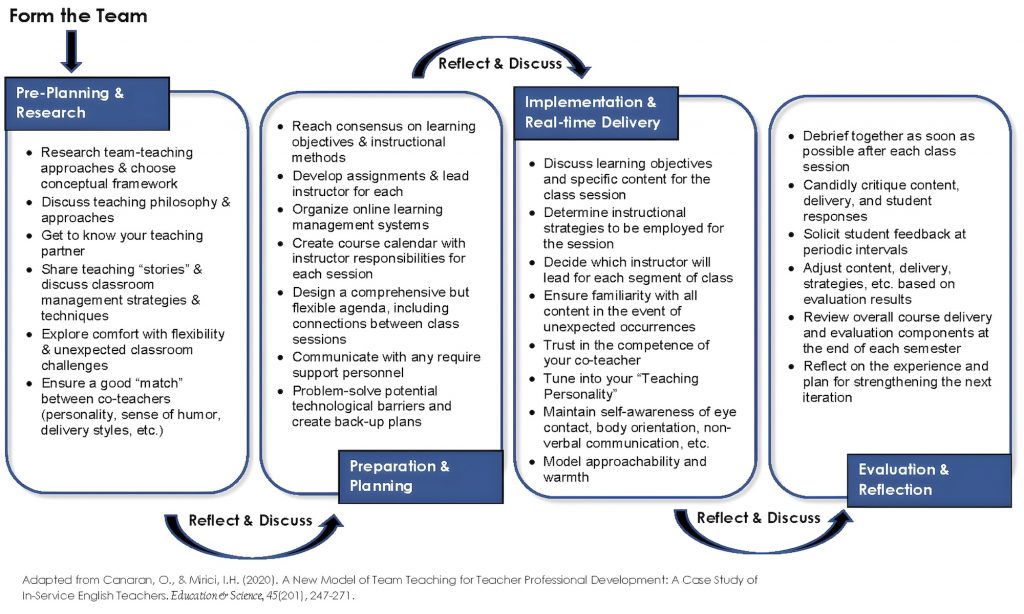

We initially developed and delivered this model in a graduate social work program delivered to seven instructional sites via IVC; with the onset of the global pandemic, it became essential to adapt the model for statewide, web-broadcast delivery (Zoom). For both delivery methods, the co-instructor model proved effective in mitigating the barriers to knowledge delivery and skill development inherent in distance education. We believe this model is generalizable and germane to an array of professional education settings and disciplines. To this end, we provide a how-to guide for designing and implementing a team-taught course in the distance education environment using various information and communication technology strategies. The following framework (see Figure 1) presents practical strategies for effective planning and preparation; responding to curriculum-related issues; addressing and managing dynamics inherent in real-time course delivery; developing professional use of self; creating a productive classroom climate; and incorporating a self-reflective process of ongoing evaluation and course improvement.

Planning and Preparation

Engaging in close collaboration and course preparation with a teaching partner allows each instructor to learn from his or her colleague’s content and teaching style. We have found that sharing course delivery with another instructor can foster a sense of competence and self-efficacy in that the combination of individual areas of strength and weakness can carry each instructor through moments of awkwardness and self-doubt. For example, when a student asks that inevitable question that catches the presently lecturing instructor off-guard, two things may occur: (1) Susan, the “stumped” professor, appears simultaneously thoughtful and collegial by inquiring, “Sean, what are your thoughts on that?” or (2) Sean proactively (but subtly) “rescues” Susan by interjecting his own answer to the student. Obviously, such attempts to help could be at best distracting and at worst dangerous to the co-instructor relationship without trust, insight into our own and each other’s areas of competence, and an appropriate lack of ego. After all, in most cases, two brains are thought to be better than one—we have had multiple experiences wherein teaching as a team has allowed us to appear twice as brilliant as we would otherwise. Between the two of us, we have over 50 years of experience as social work practitioners, as well as 28 years of higher education teaching experience. The depth and breadth of our academic and clinical practice know-how provides our students with a greater array of knowledge and examples of real-world application than could normally be embodied in a single professor. In the classroom, we are able to access and cite one another’s experiences to provide an increased diversity of illustrations that make concepts more real and generalizable to the various practice areas in which students are interested.

This brings us to a word of caution: A primary consideration of choosing to team-teach is ensuring a goodness of fit, or match between teaching partners, including such characteristics as similar teaching philosophies, flexibility, and willingness to step outside of one’s comfort zone, sense of humor, approach to student-related difficulties, and so on. As stated by Canaran and Mirici (2020), “In team teaching, it is essential to know your partner to ensure that you are compatible with one another” (p. 257). In addition, Rao and Chen (2020) state emphatically that team teachers must be granted the opportunity to choose their own teaching partners. Finally, McKenzie et al. (2020) found that when teaching teams have complementary skills and a clearly established teaching philosophy, the classroom becomes a successful mix of unique teaching styles and learning opportunities for students.

To maximize the benefits of team teaching, it is imperative that both instructors invest in careful planning prior to course delivery and systematic preparation for each class session. Intentional division of labor is critical to the successful delivery of the course from start to finish. Team teaching is most efficient when there is a clear understanding and consensus with regard to individual roles and responsibilities in teaching, student communication, and management of course business. We have found it most effective for both of us to attend every class session, which maximizes the benefits of our collaborative approach for students as well as instructors. However, team teaching reduces stress and provides continuity in the rare event that one instructor is unable to be present.

Critical elements on which to collaborate include course learning objectives, assignments, online learning management systems, course schedules and calendars, and course delivery team interfaces.

- Reach consensus on course learning objectives and design instructional methods to increase student attainment of desired competencies. Our course objectives are informed by the University’s formal course evaluation protocol (IDEA), the Council on Social Work Education’s required academic and practice competencies, and our agreed-upon ideas. We individually explore textbooks, readings, and resources related to the specific content each of us will be leading; we then arrive at a consensus on what elements will be selected.

- Develop competency-building course assignments and identify a Lead Instructor for each. For example, a required competency for a course we team teach on administration and leadership in social work states that students will “analyze, formulate, and advocate for policies that advance human rights and social, economic, and environmental justice” (CSWE, 2015). Based on Sean’s expertise in agency administration and policy writing, we agreed he would design and lead this portion of the course and coordinate and grade related assignments. The same course included a competency that required students to identify and access resources to serve client needs. Susan used her experience to design, lead, and grade a section of the course devoted to documentation of need and writing grant proposals.

- Work together to organize online learning management system elements. Based on interest and specific skills, Susan contributes to our online course interface (USU uses Canvas) by uploading readings and resources and creating platforms for student communication and weekly homework assignments. Sean formats the various structural elements of the site (site map, links, assignment tabs, etc.) and focuses on making the interface visually appealing and user-friendly.

- Create a course schedule and calendar that clearly designate each instructor’s responsibilities for all course sessions. This area of pre-course planning and preparation must be done collaboratively. We typically use a five-week module format divided into three topical areas related to course objectives. We teach the first module (Administration and Leadership Skills) together, with equally shared responsibility for course sessions, assignments, and grading. The remaining two modules (Policy Development and Grant Writing) feature a single lead instructor, with the co-instructor in a more supportive role. This includes having the lead instructor conduct course sessions, grade assignments, and respond to related communication with students. This approach allows for each of us to have our “moment of glory” showcasing the passion we have for our own areas of interest while simultaneously modeling collaboration and mutual respect (Henning Loeb, 2016).

- Communicate clearly with technology facilitators, administrators, teaching assistants, and other relevant parties to your course delivery team. We originate from two different sites, each with face-to-face students, and our cyber-classroom includes five additional receiving sites. This introduces a lot of players into the course delivery equation (site managers, technology facilitators, administration, classroom aides, etc.). Assuming that all of these individuals will somehow magically anticipate expectations is simply asking for trouble. Any schedule changes, format adjustments, or special media considerations must be communicated well in advance in order to ensure smooth delivery. During one team teaching iteration, we elected to originate from different sites each week throughout the semester in order to facilitate better connections with students. Recognizing the potential disaster this travel could create, we developed a semester-long calendar designating where in the state each of us would be on any given week. We emailed this schedule to basically everyone who could potentially be impacted by our travel, which resulted in a smoother semester. It is worth noting that although students at our rural sites loved this “rotating instructor” approach—and greeted us with potluck dinners—by the end of the semester, we were travel-worn, exhausted, committed to being somewhat less self-sacrificing in the future, and in need of new car tires. Of course, the challenges and benefits of travel became non-existent during the course of the pandemic in the Zoom-based, virtual teaching environment.

The pre-course planning process should be underway well before the course begins, and then again—more comprehensively and task-focused—shortly before the course commences. Prior to each class session, it is also vitally important to schedule team consultation and collaboration as close to actual class delivery as possible. This promotes entering class fresh with energy and your team-teaching plan foremost in your thoughts. We recommend the following as part of the planning sessions prior to each class meeting:

- Identify learning objectives and student competencies for the class session. For example, competencies for one class session included managing employees and supervising staff; recruiting, developing, and retaining staff; and the multiple roles of a social work supervisor.

- Discuss specific content, learning activities, and strategies to engage students at all sites, with a particular focus on students who do not have a face-to-face instructor. Focused on the competencies described above, we created a site-based small group discussion activity based on leadership and administration case studies. Students at each site prepared a response and presented it to the entire seven-site cohort.

- Decide which instructor will take the lead on each segment of the class. For one course session, Sean created the case studies and associated questions, and Susan facilitated the site-to-site discussion (at times akin to herding cats).

- Create a session-to-session flow by planning for follow-up from previous sessions as a bridge to future material. We plan time at the beginning of each class to connect material discussed from the previous week to the competencies being addressed in the current session and entertain follow-up questions from students. For example, in one session, we discussed a framework for various styles of leadership and supervision, and the effectiveness of each in different work contexts. As we began the next session, we invited students to share examples of the styles of leadership they had observed during the week in their employment and internship settings. As a bridge to the content of the present session, we asked students to explore and identify characteristics of the leadership style that were most congruent with their personal approach to administration.

- Consider class timing and time-management issues while creating a flexible session agenda. Our philosophy is to over-prepare and potentially under-deliver rather than run out of things to say. Following this principle, we always have an “if we have time” learning activity for each session so that we are never left empty-handed. Thus far, this strategy has never failed us. For example, as a backup plan, we prepared media clips and discussion questions that were specific to the session’s content on leadership styles. As we worked through the session, we only had time to use one of the several media clips; therefore, we posted the remaining clips on Canvas so students could access them outside of class.

- Problem-solve for potential technological and other barriers to accomplishing class session goals. We have learned from sad experiences that media and technology can never be fully trusted. We, therefore, always have a multilevel back-up plan, the most effective of which is emailing all course session material (including presentation materials, discussion questions, PowerPoints, links to media, etc.) to one another prior to class. For example, during one course session, the video we had chosen to show had no sound when it originated from Susan’s site. Since Sean had prepared to access the video clip, he was able to run it from his site with virtually no loss of class time.

When it comes to planning individual class sessions, it is essential to be intentional in the division of labor. Team teaching is most effective when instructors are equally yoked and each individual’s strengths illuminated (e.g., Sean is talented at creating engaging PowerPoint presentations, while Susan has considerable expertise in facilitating multi-site discussions—an impactful combination). Finally, to avoid triangulation—playing one instructor against another—we require that students copy both instructors on every email, text, or LMS communication.

Real-Time Course Delivery

As important as pre-course planning and preparation are, they will only get you so far without a solid plan firmly in hand to facilitate successful real-time course delivery. Rao and Chen (2020) state that working out an effective blueprint for what to teach—and how to teach it—is essential for a successful classroom experience. Beavers and DeTurck (2000) describe the process as “a semester-long jam session, where musicians who share a deep love for the material they play decide to explore its possibilities with little regard for the dangers” (p. 1). Team teaching has also been described as dancing with a “you lead, I’ll follow” theme, as well as sharing the characteristics of a high-wire act with its “I’ll start, and we’ll see what happens” impromptu dynamic (University of Western Ontario, 2002). In the classroom, we have experienced fantastic “jam sessions” and well-choreographed dance performances, along with unfortunate high wire mishaps (thank goodness there were safety nets, so we lived to teach again). These adventures have convinced us of the importance of an intentional approach to attending to all elements of real-time course delivery. We believe expecting the unexpected and trusting in one another’s competence are of paramount importance.

“Love the team-teaching approach, with each instructor able to express and capitalize on their individual areas of strength.” —Student Course Evaluation comment

- Expect the unexpected. Having a flexible class agenda is beneficial if technology or other issues deter you from your specific plan. This allows you to shift to other session elements while awaiting and hoping for resolution of the problem. For example, if one instructor experiences unexpected technological difficulties, the other instructor can take over with virtually no loss of class time or instructional quality. To illustrate, during one session, Sean repeatedly “techno-froze” mid-sentence, and Susan was able to carry the torch until he “thawed.” On another occasion, Susan was rendered “microphone-mute” for unknown reasons, and Sean took over the verbal communication. Although technological glitches cannot be fully avoided, as suggested by an analytical study from the Education and Information Technologies Journal, “proper preparation can overcome all but the most catastrophic technological failures” (Talib et al., 2021, Conclusion section).

- Trust in the competence of your colleague. Proper preparation and a strengths-based division of labor fosters a sense of trust, strengthens your foundation of collaboration, and enhances your ability to facilitate student engagement and effective learning across the miles. Having faith in your teaching partner’s ability to carry on in your unplanned technological absence promotes a sense of confidence in knowing there are options available in the event of uncontrollable glitches or other difficulties. (Trusting in your students’ desires to care and engage in their own learning is another vital element of successful real-time course delivery.)

Professional Use of Self

In the field of professional social work (as well as others), the concept of use of self is employed to describe the practitioner’s authentic application of his or her personal qualities, belief systems, and life experiences to his or her work with others (Ruan et al., 2020; Edwards & Bess, 1998; Baldwin, 2000). We find this notion to be highly relevant to teaching, as well. Walters (2008) states:

One of the most important aspects you bring to teaching is your personality. Although fundamental to teaching, the teacher’s theoretical orientation and mastery of skills appear to have the least impact on student satisfaction when compared to the social worker’s authenticity and how they use personality traits as a therapeutic tool. What is important regarding authenticity is to reflect your real self at all times. (p. 1)

Specific attention to use of self is essential to effective real-time course delivery. One fundamental element we tune into is Video Conference Personality—the manner in which you present yourself on-screen. Personality is defined as “the set of emotional qualities, ways of behaving, etc., that makes a person different from other people,” including the “attractive qualities (such as energy, friendliness, and humor) that make a person interesting or pleasant to be with” (Merriam-Webster, 2016). This definition supports the use of self-approach, and we have found that “energy, friendliness, and humor,” as well as genuine enthusiasm and passion for your topic, travel well across the miles.

Another important consideration regarding use of self is that of mindfulness regarding non-verbal communication and body language. Drawing again from our social work experience, we understand the majority of human communication is non-verbal and are aware that factors such as posture, facial expression, eye contact, and body positioning communicate interest and engagement to your audience (Cornoyer, 2014, Ivey et al., 2010; Kadushin & Kadushin, 2013).

- Eye contact. In order to appear as if you’re making eye contact with your audience, you need to look directly into the camera, at least some of the time. In many ICT settings, this may create awkwardness, as cameras may be positioned divergent from your video screen. Further, in mixed settings with face-to-face and distance students, it may be helpful to explain to students in the room that you are not ignoring them when attempting to simulate eye contact with their distance peers (Love, 2013). This recommendation is further supported by empirical studies that found eye contact is a core indicator of student’s perception of instructor attention and contributes to student engagement (Kompatsiari et al., 2021; Pi, Xu, Liu, & Yang 2020), although Pi et al. (2020) also found that instructors should not stare directly at the camera continuously throughout a lecture, and should instead use “guided gaze to draw learners” attention to the learning materials” (section 1.1). This is a particularly helpful suggestion when teaching multiple distance education sites.

- Awareness and intention with regard to self-presentation. Professional presentation and dress in a video conference context should be attended to as much or more than a face-to-face session, as it can be more challenging to convey a favorable impression. Students are tuned in to the “big screen factor” of web-broadcast course delivery. For example, Susan was interrupted by a group of students 300 miles away who had decided, “you look and talk just like Hilary Swank.” Similarly, Sean was designated as a doppelganger for Chef Gordon Ramsey, “although he doesn’t act like him”.

Classroom Climate

Team teaching makes maintaining an upbeat and engaging classroom climate significantly less stressful and more manageable, even with large numbers of students and sites. When we teach together, our focus is on keeping the environment positive, challenging, and enjoyable. Our goal is for students to walk out of class thinking critically and with concrete ideas and strategies about the topic’s application and implications. In social work, we address difficult issues that can be challenging for students both professionally and personally, as there is sometimes dissonance between the values of the social work profession and the value system of the individual student. Navigating these complexities necessitates working with intention to create a classroom that explicitly defines professional expectations, ensures emotional safety, and facilitates instructor approachability.

- Maintain a setting with professional expectations. Freeman and Walsh (2013) state, “Instructors should have strict guidelines for assignments and attendance, technology use, and classroom respect and civility” (p. 102). Accordingly, we establish clear ground rules for behavior, attendance, and student interaction. As an example, we tell students that our class is a professional commitment and if they are not able to attend this “appointment,” to please let us know in advance. This is particularly relevant in a distance environment where many of our students commute, sometimes in the harsh weather conditions of a Utah winter. Through these expectations, we communicate that we are genuinely concerned for students when they “no-show” for class.

- Provide an emotionally safe and enlightening environment. We intentionally model and emphasize mutual respect and an open exchange of ideas. The distance environment is often intimidating to students; having their comments broadcast to a host of their peers—that often cannot be seen—can contribute to student anxiety about speaking up or sharing their thoughts. Anticipating, attending to, and normalizing this dynamic empowers students to gain confidence and increase engagement. Some strategies for accomplishing this are actively inviting student participation in an intentional and systematic way, ensuring equal time and attention are given to each site and Zoom breakout room, and demonstrating patience for technologically-inherent time delays and student reticence in responding.

- Make yourself approachable to students through the use of appropriate humor (Freeman & Walsh, 2016) and self-disclosure. Relationship-building in the distance education context requires increased time, attention, and proactive outreach to students; innocuous sharing of “things that make you you” (i.e., hobbies, interests, observations, etc.) demonstrates authenticity and provides channels for forming connections.

In summary, productive real-time course delivery depends upon flexibility, trust, professional use of self, maintaining a safe and productive classroom climate, and, most importantly, having a sense of adventure. Distance education and the use of ICTs is generally a student participation inhibitor—through team teaching, we are better able to foster student involvement and investment in the learning process. At the same time, we invest in our own learning process and professional development through systematic self-reflection and evaluation.

Ongoing Self-Reflection and Evaluation

Rao and Chen (2020) identify five constraints inherent in team teaching: lack of training in collaborative delivery, lack of mutual understanding of methodology and material, conflicting teaching styles, indistinct distribution of roles and responsibilities, and limited time for planning (p. 333). Fortunately, pedagogical literature provides guidance in addressing such challenges in the team-teaching environment. Epstein and Hundert (2002) propose that “professional competence is the habitual and judicious use of communication, knowledge, technical skills, clinical reasoning, emotions, values and reflection in daily practice for the benefit of the individual and community being served” (p. 226). In the context of remote team teaching, the merits of self-reflection and evaluation are obvious in their contribution to ongoing competence-building in effective course design, well-organized preparation, and engaging real-time delivery. We use student feedback obtained via mid-semester qualitative evaluations and end-of-semester mixed methods evaluations, in addition to peer evaluations conducted by mentors and instructors outside of our teaching team. Using in-course process evaluations as well as outcome data strengthens our ability to make course adjustments mid-stream as well as to prepare effectively for the next iteration of the course. With these concepts in mind, we systematically engage in several self-reflective and evaluative practices:

- Debrief as co-instructors as soon as possible after every class session. This allows for in-depth evaluation of what went well, what could be improved, and what issues warrant following up (Canaran & Mirici, 2020).

- While the energy is fresh, candidly critique our content, our delivery, and student responses (McKenzie et al., 2020). We sometimes overtly communicate to students that we learned something from a previous class session and are implementing changes intended to improve the course. This models critical thinking, professional collaboration, and ongoing application of self-evaluation—key competencies of social work practice.

- Solicit student feedback at periodic intervals (Shah & Pabel, 2019). We use a self-developed qualitative evaluation administered via our online learning management system mid-semester. Elements include asking students for feedback on their feelings about the format of the course (lectures, media, group projects, class discussions, etc.), texts and additional readings, their personal goals for the course, and questions and concerns they may have about successful completion.

- Review overall course delivery and all evaluation components at the end of each semester, with particular attention to qualitative student comments (Marshall, 2021). This active appraisal of all course elements and associated outcomes allows us to incorporate lessons learned into future class sessions and future semesters.

We agree with Lester and Evans’ (2009) assertion that “when we are willing to engage in reflective practice with those around us, listen to the thoughts and perspectives of others, even when there is inherent risk of conflict and disagreement, the opportunity to build greater understanding emerges … [and] we make space to build something bigger than we could have built ourselves” (pp. 380–381).

Conclusion

Eisen (2000) describes team-teaching environments as “model learning communities that generate synergy through collaboration. Because the fruits of their efforts are often very visible and since team members’ excitement is often contagious, they provide inspiration for others to engage in collaboration.” (p. 12). Although there are challenges to delivering a team-taught course, we find the advantages outweigh the disadvantages—particularly in the context of a global pandemic. The process of addressing and negotiating the difficulties adds to the value of the team-teaching experience. Robinson and Schaible (1995) purport, “if we preach collaboration but practice in isolation … students get a confused message. Through learning to “walk the talk,” we can reap the double advantage of improving our teaching as well as students’ learning” (p. 59). As professional social workers and academics we do preach collaboration, we do not practice in isolation, and we have a responsibility to socialize our students in this model. While this is explicit in social work education, we believe this professional socialization is just as important in other disciplines.

While we have experienced firsthand the isolation inherent in the distance learning environment—a phenomenon exacerbated significantly by the COVID-19 global pandemic—we have also found that when used strategically and with intention, team teaching within a remote education context using ICTs contributes to student engagement and performance and may reduce technology-related anxiety for students as well as instructors. It is true that we initially turned to team teaching as a survival strategy; however, as we have engaged with the model, immersed ourselves in the pedagogy, and observed the impact our efforts have had on our students, we become increasingly convinced that team teaching is the way to go. As stated by Tucker (2016), “Our connectivity to information and to one another makes this an incredibly exciting time to teach. Our collaborations are no longer limited to a school campus, and we no longer need to feel alone in our teaching practice” (p. 87).

“Having two instructors brought greater perspective to the class.”

“Team teaching rocks!” – Student Course Evaluation comments

The model of co-instruction we have detailed above provides a framework of practical strategies for effective organization of curriculum and course structure, preparation for and management of real-time course delivery dynamics, awareness of professional use of self, maintenance of a safe and productive classroom climate, and implementation of a self-reflective process of ongoing evaluation and course improvement. Obviously, this approach necessitates up-front energy and investment, ongoing intentional planning, and collaborative trust between co-instructors; however, we believe the payoff to be both pertinent and generalizable to an array of disciplines and student contexts. We have also discovered this makes future iterations of course planning less time-intensive and course delivery more effective. Further, we have found the use of the co-instruction model to be a worthwhile and rewarding endeavor with exponential influence far beyond anything we have experienced when teaching alone via IVC. In fact, after multiple iterations of this co-instructional model, we have never had a single student complain about this approach—and we have received overwhelmingly positive feedback.

References

Baldwin, M. (2000). The Use of Self in Therapy (2nd ed.). Binghampton, NY: Haworth Press, Inc.

Beavers, H., & DeTurck, D. (2000). Shall we dance? Team teaching and the harmony of collaboration. Almanac, 46. Retrieved from http://www.upenn.edu/almanac/v46/n30/o42500.html

Bettencourt, M. L., & Weldon, A. A. (2011). Team teaching: Are two better than one? Journal on Excellent in College Teaching, 21(4), 123-150.

Blanchard, K. D. (2012). Modeling lifelong learning: Collaborative teaching across disciplinary lines. Teaching Theology and Religion, 15(4), 338-354.

Bozkurt, A. & Sharma, R.C. (2020). Emergency remote teaching in a time of global crisis due to Coronavirus pandemic. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), i-vi.

Camp, S. & Egbert, S.C. (2018). Team Teaching via Video Conferencing: Practical Strategies for Course Design and Delivery. Professional Development: The International Journal of Continuing Social Work Education, 21(1), 3-12.

Canaran, O., & Mirici, I.H. (2020). A new model of team teaching for teacher professional development: A case study of in-service English teachers. Education and Science, 45(201), 247-271.

Collins, B.C., Hemmeter, M.L., Schuster, J.W., & Stevens, K.B. (1996). Using team teaching to deliver coursework via distance learning technology. Teacher Education and Special Education, 19(1), 49-58.

Cornoyer, B. R. (2014). The social work skills workbook (7th ed.). Brooks/Cole: Belmont, CA.

Council on Social Work Education. (2015). Education policy and accreditation standards. Retrieved from http://www.cswe.org/File.aspx?id=79793

Edwards, J. & Bess, J. (1998) Developing effectiveness in the therapeutic use of self. Clinical Social Work Journal, 26(1), 89-105.ew

Eisen, M. (2000). The many faces of team teaching and learning: An overview. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 87, 5-14.

Eisen, M., & Tidsell, E.J. (2000). Team teaching and learning in adult education. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 87. Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA.

Epstein, R. M, & Hundert, E. M. (2002). Defining and assessing professional competence. Journal of the American Medical Association, 287(2), 226−35.

Freeman, G. G., & Walsh, P. D. (2013). You can lead students to the classroom, and you can make them think: Ten brain-based strategies for college teaching and learning success. Journal on Excellence in College Teaching, 24(3), 99-120.

Harris, C., & Harvey, A. (2000). Team Teaching in adult higher education classrooms: Towards collaborative knowledge construction. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 87, 25-32.

Henning Loeb, I. (2016). Zooming in on the partnership of a successful teaching team: Examining cooperation, action and recognition. Educational Action Research, 24(3), 387-403.

Hitchcock, L.I., Sage, M., & Smyth, N.J. (2019). Teaching Social Work with Digital Technology. Alexandria, VA: Council on Social Work Education Press.

Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., & Bond, A. (2020). The Difference Between Emergency Remote Teaching and Online Learning. Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

Ivey, A. E., Ivey, M. B., & Zalaquett, C. P. (2010). Intentional interviewing and counseling: Facilitating client development in a multicultural society (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Brooks/Cole.

Kadushin, A., & Kadushin, G. (2013). The social work interview (5th ed.). Columbia University Press: New York.

Kompatsiari, K., Ciardo, F., Tikhanoff, V., Metta, G., & Wykowska, A. (2021). It’s in the eyes: The engaging role of eye contact in human-robotic interaction (HRI). International Journal of Social Robotics, 13, 525-535.

Laughlin, K., Nelson, P., & Donaldson, S. (2011). Successfully applying team teaching with adult learners. Journal of Adult Education, 40(1), 11-18.

Lester, J.N., and Evans, K.R. (2009). Instructors experiences of collaboratively teaching: Building something bigger. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 20, 373-382.

Love, L. (2013). Four body language secrets to remember for your next video conference. Retrieved November 10, 2014, from http://www.pgi.com/learn/four-body-language-secrets-remember-your-next-video-conference/personality. 2014. In Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved November 21, 2014, from http://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/personality

Marshall, P. (2021). Contribution of open-ended questions in student evaluation of teaching. Higher Education Research & Development, https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2021.1967887

McKenzie, S., Hains-Wesson, R., Bangay, S., & Bowtell, G. (2020). A team-teaching approach for blended learning: An experiment. Studies in Higher Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1817887

Perron, B.E., Taylor, H.O., Glass, J., & Margerum-Leys, J. (2010). Information and Communication Technologies in Social Work. Advances in Social Work, 11(1), 67-81. Pliner, S.M., Iuzzini, J., & Banks, C.A. (2011). Using an intersectional approach to deepen collaborative teaching. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 125, 43-51.

Pi, Z., Xu, K., Liu, C., & Yang, J. (2020). Instructor presence in video lectures: Eye gaze matters, but not body orientation. Computers & Education, 144, 103713-103721.

Rao, Z., & Chen, H. (2020). Teachers’ perceptions of difficulties in team teaching between local- and native-English-speaking teachers in EFL teaching. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 41(4), 333-347.

Robinson, B., & Schaible, R.M. (1995). Collaborative teaching: Reaping the Benefits. College Teaching, 43(2), 57-59.

Ruan, B., Yilmaz, Y., Lu, D., Lee, M., & Chan, T.M., (2020). Defining the digital self: A qualitative study to explore the digital component of professional identity in the health professions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(9): e21416. https://www.jmir.org/2020/9/e21416/

Shah, M., & Pabel, A. (2019). Making the student voice count: Using qualitative student feedback to enhance the student experience. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/334719010.

Shoraevna, Z.Z., Eleupanovna, Z.A., & Tashkenbaevna, S.N. (2021). Teacher’s Views on the Use of Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in Education Environments. International Journal of Emerging Technologies in Learning, 16(3), 261-273.

Talib, M.A., Bettayeb, A.M., & Omer, R.I. (2021). Analytical study on the impact of technology in higher education during the age of COVID-19: Systematic literature review. Education and Information Technologies, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10507-1.

Tucker, C. (2016). The techy teacher: Team teaching from a distance. Educational Leadership, 73(4), 86-87.

University of Western Ontario. (2002). Team teaching (Part III, Section D of Teaching Large Classes Web site). London, Ontario, Canada: University of Western Ontario. Retrieved from http://www.uwo.ca/tsc/tlc/lc_part3d.html

Walters, H. B. (2008). An introduction to use of self in field placement. The New Social Worker: The Social Work Careers Magazine, Fall. Retrieved from http://www.socialworker.com/feature-articles/field-placement/An_Introduction_to_Use_of_Self_in_Field_Placement/