2 Research as an Exploratory Process

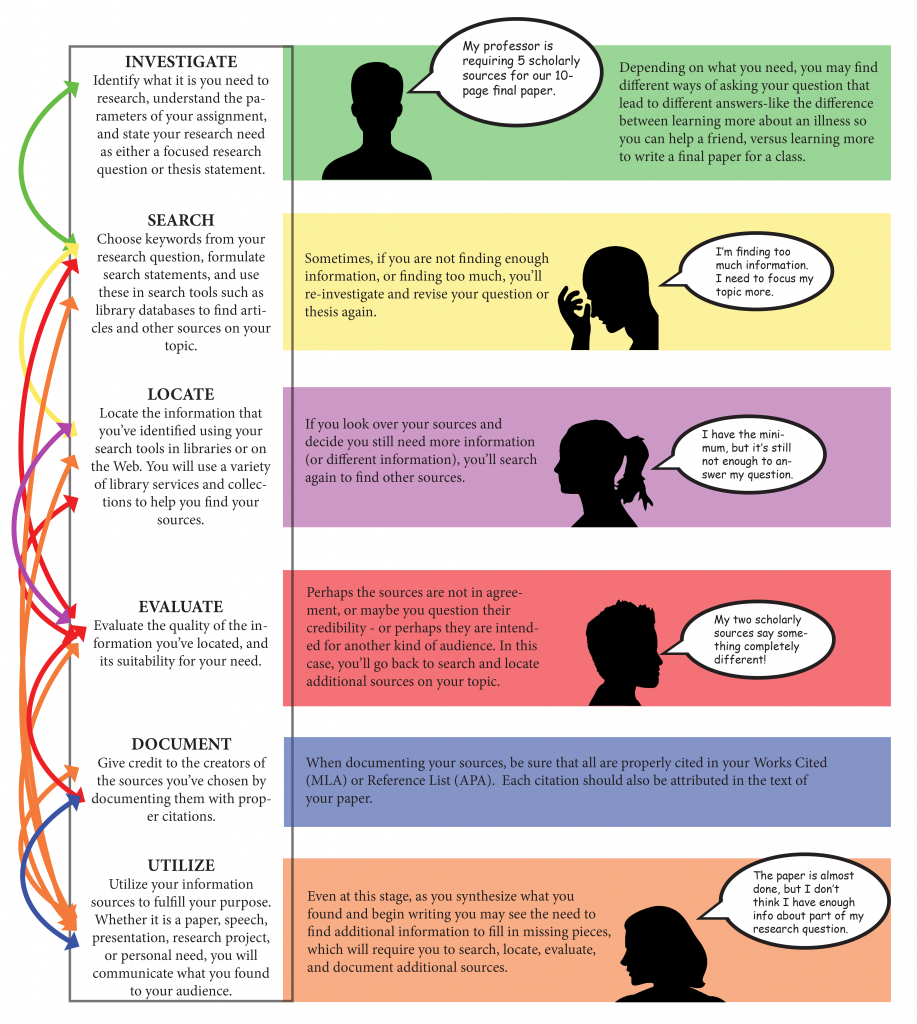

An important factor in doing college-level research is thinking about and using the components of the research process. It is important to note that the research process is not simply a series of steps that you follow in a particular order. Searching for information is often non-linear and iterative, and the components illustrated in this process may be repeated or reordered, depending on your research needs and the results you retrieve.

When people think of “the research process,” they usually think of writing papers in college. However, it is important to remember many activities outside of college also use some or all of the components of the research process. Rather than having to write a research paper, you may have a personal question you wish to explore to make some decision in your life. Or, your employer may ask you to investigate something to make a decision for work.

Below is a brief description of these components, and how they might look in college vs. real life.

THE RESEARCH PROCESS

INVESTIGATING

In college, the investigating stage of the research process involves identifying what you need to research, understanding the parameters of your assignment, and stating your research need as either a focused research question or a thesis statement. In some classes you take at Weber State University, you will be given a specific question or topic, with detailed assignment parameters, and told the exact number, types, and formats of information you’ll be required to use. In that case, your professor has already completed this step for you, and you can start your search immediately. In other scenarios, you’ll be given a general idea, and need to focus the idea based on the assignment.

For example, if you are asked to research a topic, write a 20-page paper on it, and use a minimum of eight scholarly articles, you wouldn’t want to focus it so narrowly that you wouldn’t be able to find enough information. If you are given the same topic but are only required to write five pages and use two sources, your question can be a little more focused. For example, a research question for a 20-page paper might be, “How effective is homework as a learning tool?” while a research question for a 5-page paper might be, “How effective are homework math sheets as a learning tool for elementary school children?”

A real-life example of investigating an important question to consider as a responsible information consumer might be the issue of who to vote for in a political election. While the ultimate question is, of course, who to vote for, think about the specific things you want to know to help you make this decision. For example, what issues are at stake in the election, and which of the candidates best represents your point of view or supports your needs? In this case, you are designing your assignment parameters and must decide on the number, types, and information formats to answer these questions. There are a many avenues to explore, including their ideological leanings, past voting records, and political donors or campaign contributors. You may even look at fact-checkers to see if what they are saying in their speeches is true.

SEARCHING

In the searching stage of the research process in college, you’ll choose keywords and synonyms from your research topic and use these in catalogs, databases, and search engines to find books, articles, and other sources on your topic. If you are not finding enough information, or too much, you may need to re-investigate and revise your question or thesis. Familiarize yourself with the various search tools available and learn which ones will or will not work for your project.

For example, some search tools will only find certain types or formats of information. The library catalog is a good example: if you need articles, you wouldn’t want to search the catalog because the catalog does not include articles. If you need an article on a medical topic written for the lay reader, the database MedlinePlus would not be a good choice because it only includes scholarly literature. It is often a good idea to search multiple places to find information for college-level assignments; some terms will work better in some search tools than others. Another thing to remember is that first attempts at searching often do not produce adequate results. You will probably have to try many different types of searches before you find one that works.

In the real-life example, most people have access to the Internet, which has a wealth of information on political candidates. Some well-known examples include Vote Smart, GovTrack.us, and fact-checking sites such as factcheck.org and politifact.com. From these sites you can research candidates’ ideologies, speeches, voting records, legislation, funding sources, and positions on various issues. If you can access library resources through a local public library, a college library open to the public, or a digital library such as onlinelibrary.utah.gov, a good example might be the CQWeekly Magazine database. This database provides in-depth reports on issues looming on the congressional horizon, plus a complete wrap-up of the previous week’s news, including records of political actions such as roll-call votes. As with all tools, each site has pros and cons, so be aware of any caveats for the sites you use.

For example, factcheck.org focuses primarily on federal politicians, particularly during election years, so if you are researching a state-level candidate you probably won’t find much here. As stated on the site, “In all years, we closely monitor the factual accuracy of what is said by the president and top administration officials, as well as congressional and party leaders. However, we primarily focus on presidential candidates in presidential election years, and on the top Senate races in midterm elections. In off-election years, our primary focus is on the action in Congress” (FactCheck.org, 2020, Topics section). As with college level research, search multiple places to find information, especially with controversial or current topics highlighted in the media. Remember, you may need to try multiple searches to find what you are looking for.

LOCATING

In college, once you’ve searched for information and relevant sources that fit the assignment parameters, you’ll need to locate them. Some items will be readily available online or on the shelf in the library, or you may have to use library services such as Interlibrary Loan to order them. For some items, searching and locating is one step, like when you search and find a full-text article in a database; however, sometimes more work is necessary to find the item, like a print book. If, after looking over your sources, you decide that you still need more information (or different information), you may need to search again to find other sources. Sometimes you will need to revise your search terms, or you may need to look in different places you have not searched.

In the real-life example of political candidate research, you may find most of what you need online. However, there may be sources unavailable online or through your local library. One example might be local news sources, which may be the best sources for a specific local race, or in-depth coverage of local concerns for a national race. If these are unavailable online or in physical form through your local library, they may be ordered through Interlibrary Loan, a free library service. After looking through the fact-checking sites and government records, you might dig a little deeper and find well-written biographies on the candidates, or review recorded debates.

EVALUATING

In college, once you obtain the information you need, you’ll evaluate the quality of that information. Sometimes when you get to this stage, you might realize that the information you found is inadequate. Perhaps the sources are not in agreement, or maybe you question their credibility. Or, maybe it is suited to a different audience (practitioner vs. researcher, or graduate student. vs. undergrad) or too broad in coverage. In this case, review your search and locate additional sources on your topic.

In the real-life example of researching your candidates, if you have gathered information from community groups, you may realize that some of the information you found was published by advocates of specific candidates, who will have a clear bias. You may wish to gather additional information from opponents presenting information from a different perspective. You may also want to examine information from media sources to determine whether they might be right- or left-leaning to get a broader picture of your candidate or look at sites like allsides.com which try to provide pieces from left, right, and center in one place. In all these cases it is important to try to remain objective in your research, examining the credibility of each piece rather than assuming it is all good or all bad based on who it comes from — a trap easy to fall into in these days of “fake news.”

DOCUMENTING

In college, once you have the appropriate number and types of sources you need for your assignment or project, you will begin creating or writing. As you use the information, you will give credit to the creators of the information by documenting it in a reference list or works cited list with proper, complete citations. You’ll also provide in-text citations, footnotes, or parenthetical citations (depending on your citation style) to provide attribution for the works of others you use in the paper or presentation.

In the real-life example, personal research endeavor, you will not officially document your sources. However, as you discuss the pros and cons of the various candidates with friends and family, your stance will be more credible if you can point to your sources. Deciding which candidate to vote for, based on three left-leaning sources will be less persuasive, while a longer list of unbiased sources will make a much stronger case. It will also enable those questioning your choice to review your sources and locate additional sources, possibly broadening their information base.

UTILIZING

The final component of the research process in college is utilizing the information for a specific purpose. This might be a paper, speech, presentation, or research project. Here, you will communicate what you found to a particular audience. This step begins with synthesizing the information you found; to synthesize information means thinking critically about what you gleaned from the sources you chose, putting that information into conversation with what you already know about the subject. In education, this act of creation — writing your paper or giving your presentation — is the highest form of thinking (Lundstrom et al., 2015). Even at this stage, as you begin synthesizing what you found and start writing, you may see the need to find additional information to fill in missing pieces, or you may change the direction of your paper. This will require you to go back and conduct additional searching, locating, evaluating, and documenting.

In the real-life example of looking up information on political candidates, the best way to use what you find is to exercise your right to vote and make your opinion known at the polls. Other ways of using this kind of political information may be to maintain your engagement and vote in elections that come your way: local, state, and federal. You could run for office, advocate publicly for the candidate you think is best, make phone calls to voters, write to your representative and let them know how important issues up for debate affect you or your family, or join grass-roots organizations to help change the political playing field in your area.

In this example, you are synthesizing the information you found in various sources, just as you would if you were writing a college paper. In this case, however, the information is mostly synthesized in your thoughts and ways of thinking as you expand your knowledge, rather than formally synthesizing it by producing a written document – and yet you may still find you need to go back and repeat components of the research process, as the issues of the day change or political candidates drop out or enter the race.

Sound familiar? Let’s go back to the three definitions of information (Buckland, 1991): information-as-knowledge, information-as-process, and information-as-thing. You have learned that these three definitions function as a process to further knowledge. This is the process of synthesizing information, which is the key to utilizing information, the last component of the research process. With information-as-knowledge you have an idea of what you know about the subject. You research and find sources (information-as-thing) that introduce new ideas. Thinking critically about those new ideas and using them to alter, dismiss, or support what you already know (information-as-process) is synthesis. This process takes known knowledge, knowledge known by you, and knowledge found in your research that you use to create new knowledge: the product of your research — your paper or your vote.

As stated, the research process is not a simple series of steps that produces quick results. It requires mental flexibility, creativity, and persistence when things do not work the first time. Working on research projects with deadlines requires understanding when enough information has been gathered to meet your needs.

Visual Map of the Research Process

The concept of scientific inquiry as a nonlinear and iterative process composed of several components, including Investigate, Search, Locate, Evaluate, Document, and Utilize.

One of the components of the Research Process, which involves discovering information sources to fulfill the information need identified during the Investigation component.

Involving repetition. Utilizing repetition of a sequence of operations, steps, or procedures.

One of the components of the Research Process, which involves understanding the information need and articulating it in the form of a Research Question or Thesis Statement.

A statement formally articulating an information need in the form of an explicit, detailed question to guide the Research Process; sometimes framed as a Thesis Statement.

A detailed, explicit statement formally articulating an information need to guide the Research Process; sometimes framed as a Research Question.

A main idea or important word in a research question or thesis statement; two or more keywords can be combined with Boolean Operators to form the Search Statements used to locate sources in Library Search Tools.

A word or phrase that means the same as another or can take the place of it, sometimes in a particular context; particularly useful when using Keywords to build Search Statements with the Boolean Operator, OR, or when searching for information on a topic which can be referred to in many ways, such as college students (i.e., undergraduates, university students, graduate students) or climate change (i.e., global warming, sea level rise, green energy, renewable energy, CO2, greenhouse gas, carbon footprint).

An interface for a computer program hosted on a website that indexes information and allows Internet users to search through online content, generally using Natural Language Queries, and which typically returns results that include Websites and Webpages.

Traditionally a written or printed work consisting of pages glued or sewn together along one side and bound in covers, also available in audio, electronic, and braille formats, making it both a Multi-Format Information source and one of the Long Formats of information.

A Library Search Tool where information about the library’s book collection is kept and made searchable, to allow users to discover and locate needed information

One of the components of the Research Process, which involves retrieving information sources discovered through Searching.

A type of Reference Source providing information about the lives of people.

One of the components of the Research Process, which involves the practice of appraising the value of an information source both in its own right and as it relates to your topic, typically by investigating its Authority, Credibility, Currency, Bias, and Documentation.

The quality of believability; the ability of an author or work to inspire trust based on the author’s expertise, training, credentials, objectivity, or other factors of Authority. An important consideration in the Evaluation of Information.

A preconceived opinion in favor of or against a thing, person, group, etc. which may lead to partiality in information sources. Types of bias include Funding Bias, Media Bias, and Selection Bias.

The opposite of Bias; the quality of being impartial or neutral.

One of the components of the Research Process, which involves providing References in a work to show a reader where to find the information the author used to create their work; usually includes Attribution and Citing.

An indicator, formatted according to a consistent style (such as MLA or APA), that material used in a work is originally from another source, usually included in the text and/or in a list appended to the work.

A reference made in parentheses within the text of an article, book, etc., generally including author, year, and/or page number information, to indicate to the reader where information was found, which is paired with an entry in a Bibliography to make a complete Citation.

Giving credit to the creator or copyright holder of a work whose information you used in your own work, generally by including an In-Text Citation or Parenthetical Citation.

One of the components of the Research Process, which involves synthesizing what you found and and identifying additional information that may be missing.

One of three parts of Michael Buckland’s concept of Information; the information contained in your own mind; what you know.

One of three parts of Michael Buckland’s concept of Information; the information you receive that supports, contradicts, or alters what you know.

One of three parts of Michael Buckland’s concept of Information; a vehicle of information that allows it to be transmitted, such as a document or website.