3 Kinds of Information

Information is created to deliver a message. Every day, we receive different types of messages, in various formats. This chapter will provide an overview of these messages, their purposes, and how they are packaged.

SHORT FORMATS

Some of the messages we receive are short and intended to convey an idea or reaction through a word a few words, or an image. Short formats include lapel pins, mottos, slogans, logos, brands, X posts, artifacts, banners, or billboards.

A logo is intended to get people to associate an image with a company or brand. If a logo is successful, consumer recognition will become automatic. For example, when one sees the yellow double arches, one thinks of McDonald’s. The white apple symbol is associated with Apple Computers, and the “swoosh” is associated with Nike products. A motto or slogan is intended to make a statement of belief or expectation but can conjure images in people’s minds. For example, McDonald’s uses the motto “I’m lovin’ it,” and KFC uses the motto “Finger Lickin’ Good.” Others, such as Ford’s “Quality is Job One” or IBM’s “Think” send a message to company employees and consumers.

Another type of short format information can be found on X, an electronic messaging service that allows users to send short messages called posts to their followers — other users who subscribe to receive their posts. The purpose of a post is to quickly send a brief message to a select group of people. This type of message is not very detailed (280 characters or less) but is meant to provide brief information, updates, or promote awareness.

Artifacts are physical things that people use for research, like fossils, furniture, coins, plant or animal specimens, tools, and clothing. Others include works of art (e.g., paintings or sculpture), architecture (e.g., buildings), or musical instruments.

LONG FORMATS

Long format options are used when one needs to convey more information than is possible in an X post or a motto. Examples include books, newspapers, magazines, journals, blogs, websites, and webpages.

BOOKS

Books have been around for centuries, and formats include print, electronic, and audiobooks. They can be found in library databases, online search engines, physical and online stores like Barnes and Noble or Amazon.com, and websites like Project Gutenberg. Books are cited differently, depending on where you find them and how much of them you are using (e.g., the whole book or a single chapter).

Typically, books take several years to create and are not published on a regular schedule. Scholarly books often require a proposal, research, synthesis, and editing before publishing. They typically contain extensive bibliographies which provide additional sources of information. On the other hand, popular books can be rushed into publication because they aren’t carefully researched and represent a quick profit (such as unauthorized celebrity biographies). While they might be good sources for topic ideas, they are usually ill-suited for most research topics.

Books are great for a broad overview of a topic and are more comprehensive in their coverage. Because of their length, they can explore more aspects of an issue in greater detail. One disadvantage of books is that they are not a good source for current events since they take so long to be published. Also, because of their length, they typically take significantly longer to read than articles.

PERIODICALS

Newspapers are designed to provide current news, and may be found in print, library databases, or the Web. Newspapers make up some of the category of sources called periodicals, as they are published periodically, such as daily, weekly, or biweekly. Some are broad-based sources of information, while others are specialized, providing news of a particular geographic locale, political party, or subject category. They are typically good sources for local interest issues. The content found in newspapers is written by reporters or journalists.

Magazines are similar because they are periodical publications written for the general public. Some are more news-focused, and some are entertainment-focused. Both newspapers and magazines are controlled by organizations, usually for-profit, that produce the information for the general public or for specific groups of people. The organization hires people to write and publish the information according to specific standards set by the organization for content and style; information is filtered and selected by the organization. The quality of these publications varies from poor (sensational magazines like National Enquirer) to substantive sources, such as The Economist.

Scholarly journals are written by experts in specific fields, targeting a particular discipline. Many — but not all — are peer-reviewed, meaning other experts in the field review the articles before they are published. Scholarly journals are also periodical publications, typically published less frequently than newspapers or magazines, so they are not the best format for current information. The language is customarily very dense and difficult to understand unless you are a scholar or expert in that field. They are often extremely expensive. Bonnie Swoger (2012), a Science and Technology Librarian at a small public undergraduate institution in upstate New York, published a blog that discussed a library session for biology students where she noted that “You can get a year of People for just $100, or a year of Scientific American for only $25… [but] a library subscription to the Journal of Coordination Chemistry (24 issues per year) costs $11,367 per year” (para. 3). The expense of these publications limits access for many people, which is paving the way for the open-access movement, discussed in Chapter 7: Using Information Ethically.

BROCHURES

While a brochure would appear to fit into the “short format” category, it delivers more information than could be contained in a logo or an X post. Consider the information you might find in a travel brochure to visit a foreign country. There could be information on weather, safety, transportation, leisure activities, culture, cuisine, hotels, car rental, pictures of tourist destinations, etc. While much shorter than a travel book, there is enough information presented in this small source to give people a good idea of whether they might want to travel there. While some brochures are informative, others are designed to sell or advertise.

BLOGS

A blog, or weblog, is found on the Web and usually provides commentary on a specific topic, though some more closely resemble diaries. Blog posts are typically displayed in reverse chronological order. Most are published by individuals, though “multi-author blogs” (MAB) have become more popular. These are often written and edited by news outlets, advocacy groups, educational institutions, think tanks, etc. Many blog entries include text, images, and links to other sources, and readers can publicly comment on their content. Social news sites, such as Reddit, allow readers to interact by voting for articles and commenting on them.

WIKIS

Wikis differ from blogs in that they allow users to change the content of the wiki pages, not just to post comments about the content. Wikis such as Wikipedia can be publicly accessed and edited by any user. However, wiki software can also support more private collaboration projects, where only group members can see and edit the wiki content. Most wikis are a bit like a user-created and user-edited encyclopedia, where the content may be general, such as Wikipedia, or subject-specific, like the Pokémon Wiki, which focuses on information about the imaginary creature of Pokémon.

WEBPAGES/WEBSITES

Most people have used the Web for research at one time or another. One of its strengths is the ability to explore a particular topic by clicking links from one webpage to another, or from website to website. The Web often provides immediate access to breaking stories that will normally take a day to appear in newspapers. In addition, it provides information and coverage on almost any topic, through various perspectives.

The quality of the information you find on the Web varies widely, and it can be challenging to verify the credibility of a particular site. In addition, the Web is inorganized; pages may not be archived or preserved, and what you find today might not be there tomorrow. Many pages include advertising which can lead to bias, and some information on the Web may require a subscription or fee to access.

When you use Google or another search engine, you will typically receive results that include a combination of websites and webpages. A website typically consists of multiple related pages organized by content or purpose. These pages can generally be found on the website’s home page through menus or links. For example, the home page of the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke allows you to search for a specific topic related to neurological disorders such as epilepsy. You can search their A to Z index of disorders or use the provided links to access specific pages.

On occasion, it may be appropriate to cite an entire website; however, you generally want to use the most specific information for research, making webpages the most common point of reference. Using the previous example, instead of citing the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke website: https://www.ninds.nih.gov, you would cite their Epilepsy page: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Epilepsy-Information-Page. One way to distinguish between websites and webpages is to think of websites as a book, with webpages being pages in that book.

REFERENCE SOURCES

Consider reference sources as sources you refer to rather than read cover to cover — hence the name “reference.” These sources generally summarize topics or assist in finding secondary literature. Their purpose is to provide background information, short answers to simple questions, or to help you find other sources. They are also great for quick facts, statistics, or contact information, and can be useful for learning specific vocabulary. Many contain great bibliographies for further reading or additional sources on your topic.

In short, they can be a great starting point for research. After reading about a topic in an encyclopedia or other reference source, you should have a better idea of how to focus your topic and where to look for further information.

Most print reference sources cannot be checked out from the library. However, online reference sources are available on the library’s website and can be accessed from off campus, though some require that you be affiliated with the university. Below is a list of the most common types of reference sources, with examples:

Dictionaries define words and illustrate pronunciation. They are also used to find out how words are utilized, help locate synonyms and antonyms, and trace the origin of words. Examples of general dictionaries include Merriam-Webster’s Dictionary and the Oxford English Dictionary. Examples of subject-specific dictionaries include the Dictionary of Music Education and the Dictionary of Soil Science. An online example is the Dictionary of Slang.

Bibliographies provide lists of literature on a specific subject or works by a particular author. One example is the Bibliography of American Literature.

Concordances are alphabetical listings of keywords or phrases found in the work of an author or work in a collection of writings. Examples include the Concordance of Federal Legislation and the Topical Bible Concordance.

Biographies are sources of information about a person’s life. Examples are the Twentieth-Century British Humorists and Who’s Who in America. An example of an online biographical reference source is Biography.com.

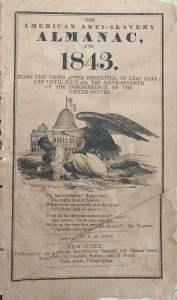

Almanacs are typically single-volume works with a compilation of specific facts and statistics. Examples include The World Almanac, Book of Facts, and Information Please Almanac. Information Please is also available online.

Directories list contact information for individuals, companies, organizations, and institutions. Examples include the Directory of Corporate Affiliations and the Encyclopedia of Associations.

Encyclopedias cover topics in a comprehensive, but concise fashion. They are useful for providing facts and a broad survey of a topic, often written by specialists. While encyclopedias are good for background information, and to lay the groundwork for understanding a topic, they are not typically cited as sources in a college-level research paper. If students want to use encyclopedias, they should use specialized encyclopedias that go more in-depth. Examples include general encyclopedias, such as the World Book Encyclopedia or Encyclopedia.com, and subject-specific encyclopedias, such as the Encyclopedia of Education or the Encyclopedia of Philosophy of Education.

Manuals provide “how to” information, such as how to write a correct citation. An example is the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 7th Edition.

Handbooks provide a concise overview of single topic, including directions and examples. Examples include the Handbook of American Popular Culture and the Business Plans Handbook.

Guidebooks provide detailed descriptions of places, intended for travelers. They often include both maps and geographical facts. One example is this historic Guidebook of the Western United States.

Guidebooks provide detailed descriptions of places, intended for travelers. They often include both maps and geographical facts. One example is this historic Guidebook of the Western United States.

Atlases are books of maps and geographical information — not just maps showing how to get from A to B, but also maps that show climate, crops, population, etc. Examples include the World Atlas of Military History and Atlas of the Great Plains. The Census Atlas of the United States is available online.

Gazetteers are dictionaries of geographical places. Examples include the Historical Gazetteer of the United States and the Utah Atlas & Gazetteer.

CONFERENCE PROCEEDINGS/RESEARCH REPORTS

Researchers present papers and research reports at conferences to describe their current research. These papers are often published in a volume called a conference proceeding. While this information can be published in scholarly journals, the process can take months. Sometimes proceedings are treated like individual books, while yearly conferences are treated like journals. So, instead of a single record for each conference, there is a single record (usually in the library catalog) for all the years of that conference’s proceedings. Sometimes conference papers are not published and may only be available from the authors, which makes them difficult to find.

MULTI-FORMAT INFORMATION

Much of the information available today is available in multiple formats. Books are the most obvious example of multi-format information. A single book can be published in print, as an audiobook, or made available electronically through library databases, the free Web, or via Kindle or Nook. Similarly, articles are available in print, via a subscription library database, or the free Web. However, sometimes, the version you find for free can be different than the one offered through a subscription service.

One of the advantages of multi-format sources is that users can choose their preferred method of viewing. For example, this textbook, available for free on the Stewart Library website, can be downloaded in PDF format and viewed on a large-screen computer, tablet, or phone. Readers may print sections or check out a bound copy from the library’s Reserve collection. While some like the feel of an actual print book, others prefer to read online; some online readers are comfortable reading on a small screen, while others prefer to sit in front of a large monitor to view the content.

AUDIO-VISUAL FORMATS

Audio-visual formats include videos, online games, documentaries, speeches, songs, movies, plays, photographs, paintings, pictures or illustrations, and numerical information in charts, graphs, diagrams, word clouds, tables, or infographics. Visual information can tell a story, explain a concept, or stimulate an emotion. Social media and photo- and video-sharing websites, like YouTube, Flickr, and Vimeo, allow viewers to interact by sharing photos or videos and commenting on user submissions. As with all information, it is essential to consider the information’s source and cite these sources when you use them.

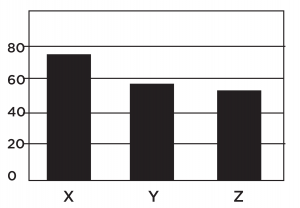

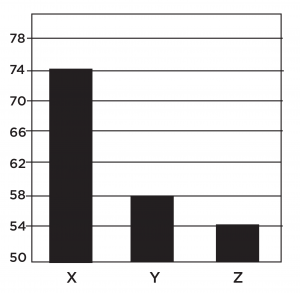

Visual information does have some caveats. First, people may see different things when viewing images. Critical pieces of the image could be ignored or missed, and people with different backgrounds and experiences may have different perspectives. Second, images will sometimes appear very different depending on whether they are viewed in person, in a high-quality print publication, on a computer, or on a small device such as a cell phone. In other words, different devices can change the message. Third, statistics presented in visual form, such as charts, graphs, or infographics, can distort or misrepresent what the numbers are telling you. Sometimes this is deliberate, and sometimes people don’t understand the data. For example, a vertical scale can be too big or too small, skip numbers, or not start at zero. Other times the graph is incorrectly labeled, or data is left out.

Look at these two graphs. Though the numbers are the same (X=75, Y=58, Z=54), the way each graph presents them makes a very different impression. The chart on the right implies that X is three times as great as Y, and nearly six times as great as Z. However, note that the vertical axis of the chart starts at 50 and goes up by increments of 4, making X, Y, and Z look farther apart. On the other hand, the vertical axis of the chart on the left starts at 0, and rises by increments of 20, more accurately depicting the relationship between X, Y, and Z.

INFORMATION TYPES

Sometimes, when given an assignment, you must use a specific source type. The previous section discussed formats of information, which tell you what it is (a book, article, webpage, blog, etc.). This section discusses types of sources and describes what kinds of sources they are.

PRIMARY & SECONDARY

At some point you may have a professor who requires you to find primary research articles. How can you know if you’ve found the right kind of source for the assignment? Think of primary sources as first-hand accounts or reports written by the person or people who experienced the event. A primary research article will be one in which the authors of the article are the same people who conducted the research, analyzed the results, formed conclusions, and reported their findings and methodology in the article. Primary sources may also include diaries and journals, autobiographies, case studies, memos, photographs, fiction novels, and eyewitness newspaper articles written at the time of the reported event.

Secondary sources review and summarize the research conducted by others. Articles in which the authors study and analyze past events they did not experience are also considered secondary sources. Other secondary sources include encyclopedia articles, biographies written by someone other than the subject, scientific literature reviews, and textbooks.

SCHOLARLY, POPULAR, & TRADE

For college-level work, you will often be required to use academic scholarly sources, though sometimes it might be okay to use popular sources or trade publications. While general characteristics can distinguish each source type from another (see below), it is important to remember that many sources will not match all the characteristics of a particular source type. For example, Scientific American has glossy pages and color pictures but includes scholarly articles and those geared toward a more general audience. The American Journal of Nursing is a glossy trade publication that includes both popular and scholarly articles written for those in the nursing profession.

It is important to point out that the following table is focused primarily on articles. Other formats like books, videos, and websites, may be classified as scholarly, popular, or trade. These are just general guidelines.

POPULAR

Authors of popular sources can be freelance writers, journalists, staff members, and occasionally scholars. Their credentials are usually not provided. Sometimes articles written in popular sources are unsigned. Content in these publications is usually wide-ranging and covers many topics. However, some may focus on news or current events, others on how-to or “DIY” tips, and others on a limited topic (sports or cooking). The intended audience for these publications is usually nonprofessionals or the general public. Some are intended for a more educated readership, but still a general audience. Advertising for these publications is fairly heavy, including glossy photos, but the type of advertising depends on the magazine and its intended audience. The purpose is to make money, provide general interest information to a wide audience, entertain, advertise, sell products, encourage subscriptions, or promote a particular viewpoint. Concerning accountability (quality control), these typically undergo editorial review. Some may use unidentified sources or give a “suggested readings list” but will not have a formal bibliography or footnotes. These works are usually published by commercial presses and specific interest groups.

SUBSTANTIVE

Publications that fall under this category are considered popular, meaning they are not scholarly, but articles are generally of a higher quality than those in a typical popular source, putting them into something of a “gray area” between the two. Terms used in these publications may be more sophisticated than you might find in People Magazine or Better Homes and Gardens, and may even report on others’ discoveries or progress in research. Examples that fall under this category might include National Geographic, Science Magazine, and Time Magazine.

SCHOLARLY

Authors of scholarly sources are typically experts, scholars, researchers, or authorities in their field. Their credentials are almost always provided. The intended audience for these publications includes researchers, scholars, experts, professionals, and the college and university community. Content in these publications typically covers a single discipline, including original research, meta-analysis, literature reviews, or theoretical discussion of a specific topic. Articles in scholarly publications usually include both abstracts and extensive references to sources cited, as well as extensive use of jargon and the discipline’s terminology. There is typically very little, if any, advertising. There may be a few ads for conferences, job openings, and professional publications and journals, or for specific items related to that field of study. Their purpose is to contribute to the scholarly conversation by exploring theories, presenting new ideas, inviting discussion, and generally adding to the body of research and guiding future research in a particular discipline. Regarding accountability, scholarly sources also undergo an editorial review, but some (not all) are also subject to an additional quality control process called peer review.

TRADE

Authors of articles from trade publications may be field or industry specialists (like substantive publications), staff writers with expertise (like popular publications), and occasionally, scholars who work in that field (like scholarly publications). Their credentials are usually provided (like scholarly) but not always (like popular or substantive). The intended audience includes people in specific trades, industries, professions, or employment seekers in specific industries. Content in these publications may include industry trends, new products or techniques, organizational news/industry forecasts, or job openings in that profession. Language may exhibit extensive use of jargon and terminology of the industry or trade (like scholarly). These publications may include original or industry-related research (like scholarly). There is typically a moderate amount of advertising. Most, if not all ads are trade-related and directed to specific industries and professions. The purpose is to provide industry news, contacts, and updates, keep trade professionals informed, and contribute practical knowledge to industry professionals or practitioners. Concerning accountability, articles typically undergo an editorial review by those in the field (substantive or scholarly). Articles may have a limited reference list or bibliography (substantive or scholarly), usually published by trade or professional associations, corporate, or commercial presses. As demonstrated here, trade publications can have characteristics seen in all three types of sources: popular, substantive, or scholarly.

Examples of popular/substantive trade publications include Architecture Today, Pharmacy Times, or The Economist. Examples of scholarly trade publications include the Journal of Academic Librarianship and the Journal of Educational Computing Research.

In the next section we learn more about popular and scholarly resources, and how to tell the difference. But first, a note about trade publications. “Trade” refers to a job or field of work. When used to describe a resource, trade generally refers to an entire publication (not just an article) written about a particular trade. Articles in trade publications are typically written by practitioners, for practitioners — that is, they are written by people practicing their trade, for other people practicing their trade.

A single trade publication may include some popular and scholarly articles, or lean towards one over the other. However, it is important to evaluate an article’s merits, determining whether it is popular or scholarly, instead of assuming a trade publication includes only one type. They may share general news, trends, practical advice, opinions, or research. Authors may be PhDs using sophisticated language, practitioners using jargon, or editorial staff using layman’s terms. Some articles may provide the author’s credentials and lists of references, while others may include only one or the other, or neither. Some trade publications appear glossy, like a magazine, and some look more like a traditional journal. In fact, some people call them either trade magazines or trade journals.

The bottom line is that if something is called trade, the article could be trade-popular or trade-scholarly. Suppose you are unsure whether your resource is a trade publication. In that case, the title may give you a clue: Middle School Teacher is written for middle school teachers, Advertising Age is written for people in the advertising field, and Pharmacy Times is written for people working in pharmacies or the pharmaceutical industry.

DETERMINING WHAT TYPE OF SOURCE YOU HAVE

Don’t confuse primary and secondary sources with popular and scholarly sources. Think of primary and secondary sources in terms of the author — did the author experience the event they are writing about or write with first-hand knowledge of the research they conducted?

Think of popular and scholarly sources in terms of the audience and content. An article that reviews and summarizes multiple research studies would be a secondary source. If the article is written for scholars or researchers in a field and lists numerous references, it is categorized a scholarly secondary source. If the article is aimed at the general public, it would be a popular secondary source.

Another misconception is that scholarly sources are better than popular sources. While that is sometimes true, popular means it is written in a way easily understood by most readers. For example, an article titled “Fossil Moon,” published in the October 2017 issue of Scientific American, discussed a study about oxygen that comes from Earth to the moon. The gist of the article was that studying lunar soil could tell us more about Earth’s atmospheric history. This concise two-page summary was written for an educated but non-specialist reader. In contrast, when the study was published in the January 2017 issue of Nature Astronomy, the in-depth scholarly article used complicated jargon and a lengthy bibliography. Both discuss the same thing, but one is a shorter easy-to-understand summary, while the other is a lengthy complicated piece.

Following are a few more examples:

Secondary & Scholarly Article

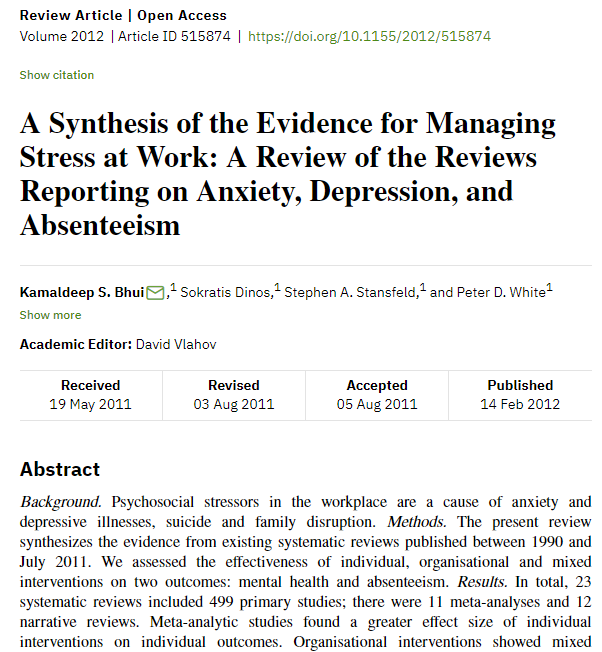

The following article is a synthesis of literature (secondary) on managing stress at work, published in a peer-reviewed (scholarly) journal.

Primary & Trade Article

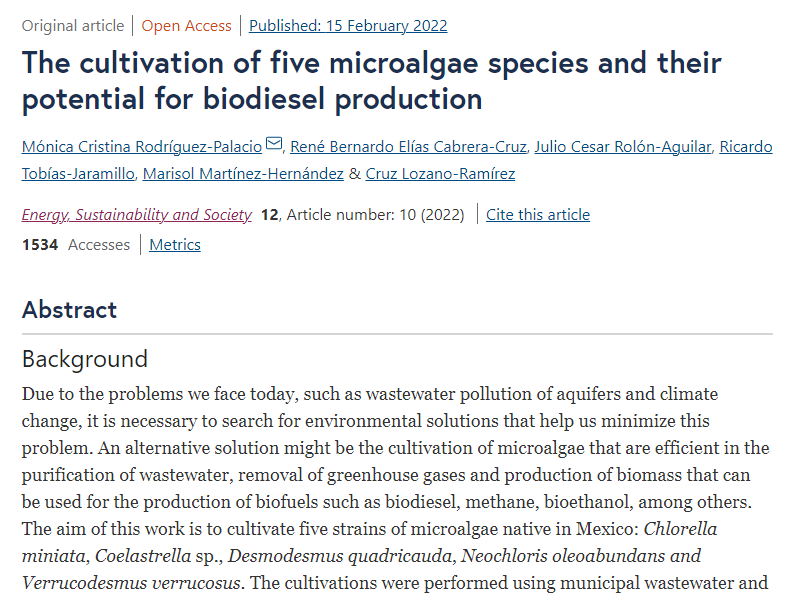

The following article provides information for individuals in the field of energy and sustainability, making it a trade publication. However, it is also a report on original research, which makes it a primary source.

Primary & Scholarly Article

The following is a report on research done by the author. It is published in Observational Studies, an open-access, scholarly peer-reviewed journal. Since the author conducted the research themself, it is considered primary.

Primary & Popular Book

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, An American Slave is a primary and popular book. This book is an autobiography (primary) written for the general public (popular).

Primary & Popular Webpage

This webpage presents an eyewitness (primary) newspaper account (popular) of challenges for university students with disabilities.

Secondary & Scholarly Book

Here is an example of a secondary & scholarly book. The Computer: A Brief History of the Machine That Changed the World is a book detailing the history of the invention of the computer with footnotes and a bibliography. The language used is suited to an educated audience, and the authors are faculty members in the History Department and the School of Computing at Weber State University.

Secondary & Popular Book

The Northern Navajo Frontier 1860-1900: Expansion through Adversity, written by Robert S. McPherson for the general public (popular), pulled information from many sources (secondary) to present an account of the Navajo Nation from 1860-1900.

Secondary & Trade Book

Secondary & Trade Book

The Business Guide; or Safe Methods of Business, by J. L. Nichols, is a book that provides instruction on all things business. This source compiles business advice from notable business men of the day (secondary). The intended audience is individuals interested in pursuing the business (trade).

Primary & Popular Book

Works of fiction are considered primary sources. To Kill a Mockingbird is the fictional creation of Harper Lee (primary) and is written for the general public (popular).

Primary & Neither Popular or Scholarly

Some sources, such as interviews, diaries, and photographs are primary sources if they are created at the time of the event but are not considered either popular or scholarly. The photograph below depicts a farmhouse in Dalhart, Texas surrounded by sand dunes.

A NOTE ABOUT SCHOLARLY & PEER REVIEW

Most scholarly articles are also peer-reviewed, so terms are often used interchangeably. However, they do not mean the same thing. As noted previously, a publication is regarded as scholarly if it is authored by experts, for experts. Its focus is academic, often reporting original research (experimentation) or theory. Publishers of scholarly works are typically professional associations or academic presses. However, while it can be assumed that all peer-reviewed articles are scholarly, not all scholarly articles are peer-reviewed.

In addition to being written by experts and published in scholarly journals, peer-reviewed articles must go through a rigorous assessment before publication. They are examined and evaluated by the author’s peers (experts in the same subject area), who may make recommendations to improve the quality of the article or even recommend against publication if it is not up to the expected standard. In some cases, the review is a “blind” or “double-blind” peer review — in these cases, the reviewers don’t know who wrote the article, the author doesn’t know who reviewed it, or both. Peer-reviewed periodicals publish articles only if they have passed through this official editorial process. The peer review and evaluation system intends to safeguard, maintain, and improve the quality of the scholarly articles published in academic journals.

One of the Formats of Information, which includes Mottos, Slogans, Tweets, and Artifacts.

One of the Short Formats of information, also referred to as a Slogan: a brief statement of belief or expectation, sometimes used formally by organizations, groups, or companies.

One of the Short Formats of information, also referred to as a Motto: a brief statement of belief or expectation, sometimes used formally by organizations, groups, or companies.

One of the Short Formats of information: a brief message posted by a user on the social media platform, X.

Physical things that people use for research, including fossils, furniture, coins, plant or animal specimens, tools, clothing, works of art or architecture , or musical instruments; considered a Short Format of information.

One of the Formats of Information, which includes Books, Brochures, Periodicals, Blogs, Wikis, and Websites.

Traditionally a written or printed work consisting of pages glued or sewn together along one side and bound in covers, also available in audio, electronic, and braille formats, making it both a Multi-Format Information source and one of the Long Formats of information.

A type of Periodical, containing articles and some photographs and advertisements. Often specific to a city or region; sometimes covering a particular subject or area such as business or finance. Typically a Popular Source.

A type of Periodical, containing articles, illustrations, and advertisements, and sometimes covering a particular subject or area such as hobbies, popular culture, or parenting. Typically a Popular Source.

A regularly updated website or web page written in an informal or conversational style, usually by one person or a small group of contributors; short for “Web Log.” One of the Long Formats of information.

A collection of information hosted online with a common URL, usually found by searching a Web Search Engine or navigating directly to a known URL, and generally made up of several related Webpages and organized by the inclusion of a menu linking the pages together.

One of the Long Formats of information: a part of a larger Website, usually linked to by a menu or table of contents on the main page (or homepage), like a page in a Book.

An electronic collection of information resources, generally including periodical articles, books, and audio-visual material, to which the library subscribes through the services of database vendors.

An interface for a computer program hosted on a website that indexes information and allows Internet users to search through online content, generally using Natural Language Queries, and which typically returns results that include Websites and Webpages.

The oldest existing organization with the aim of digitizing books in the Public Domain, or with permission from the holder of the Copyright, and making them freely available to the public.

An information source intended for the general public, rather than professionals or scholars in a particular field as is the case with Trade Publications and Scholarly Sources; typically written by journalists or other authors who do not provide credentials; generally, they do not include a list of references.

A type of Reference Source providing information about the lives of people.

A single publication with new issues published on a regularly scheduled basis, such as daily, weekly, monthly, or quarterly, and generally including Newspapers, Magazines, and Scholarly Journals.

A type of Periodical containing articles written by experts in specific disciplines, often Peer Reviewed.

A process some scholarly articles go through prior to publication, where scholars in that field read and review articles submitted for publication, usually with the option to require edits, approve, or deny publication, and often without knowing the name of the authors.

A movement to counter the for-profit scholarly publishing industry and establish a model of authorship and publication that focuses on dissemination and sharing of information rather than profit, whereby authors pay publishing costs and keep the Copyright for their work, enabling readers to access articles, etc., for free.

A pamphlet or booklet, particularly one containing descriptive information and pictures of a product or service. One of the Long Formats of information.

A Long Format of information, created online but similar to an Encyclopedia in format and content (either general or topic-specific) but editable by users.

A Wiki open to and editable by the public, with very broad topic coverage, that can be a useful tool for the beginning stages of the Research Process, such as choosing a topic or finding Keywords, but which is generally not considered to have sufficient Credibility to be used as a source for college-level research

A type of Reference Source that provides information about topics in a comprehensive, but summary fashion, like an overview. They are useful for providing facts and giving a broad survey of a topic, and are often written by specialists.

The quality of believability; the ability of an author or work to inspire trust based on the author’s expertise, training, credentials, objectivity, or other factors of Authority. An important consideration in the Evaluation of Information.

A preconceived opinion in favor of or against a thing, person, group, etc. which may lead to partiality in information sources. Types of bias include Funding Bias, Media Bias, and Selection Bias.

One the most commonly used Web Search Engines, used widely to search for information on millions of topics. Also used as a verb, meaning to use a Web Search Engine to search for information.

Giving credit to authors of whose works are used to inform new works, often by Summarizing, Paraphrasing, or Quoting, and providing Attribution, thereby informing readers of where the information came from.

An information source typically used as a starting point for research or to look up facts, definitions, overviews, and other information, including Almanacs, Atlases, Bibliographies, Biographies, Concordances, Dictionaries, Directories, Encyclopedias, Gazetteers, Guidebooks, Handbooks, and Manuals.

A type of Reference Source which defines words, illustrates pronunciation, describes etymology (word history or origin) and usage, and lists synonyms and antonyms.

A word or phrase that means the same as another or can take the place of it, sometimes in a particular context; particularly useful when using Keywords to build Search Statements with the Boolean Operator, OR, or when searching for information on a topic which can be referred to in many ways, such as college students (i.e., undergraduates, university students, graduate students) or climate change (i.e., global warming, sea level rise, green energy, renewable energy, CO2, greenhouse gas, carbon footprint).

A type of Reference Source comprised of a list or lists of works on a specific topic, by a specific author, or printed by a specific publisher. May also be used to refer to the list of works used in a journal article or book, also called the "References" or "Works Cited."

A type of Reference Source providing alphabetical listings of keywords or phrases found in the work of an author or works in a collection of writings.

A main idea or important word in a research question or thesis statement; two or more keywords can be combined with Boolean Operators to form the Search Statements used to locate sources in Library Search Tools.

A small group of words standing together to represent a concept or name of a place, person, or thing, such as United States, Rosa Parks, or air conditioner, used in Phrase Searching.

A type of Reference Source, usually in a single volume, which collects facts and data such as statistics.

A type of Reference Source that provides lists of contact information for individuals, companies, organizations, and institutions.

A type of Reference Source providing information about how to do something, such as write a citation or fix a car.

A well-known and respected professional organization representing psychologists and psychological research in the United States, whose purpose is to create, communicate, and apply psychological knowledge for the benefit of society.

A type of Reference Source providing a short overview of a broad topic, often including directions or examples.

A type of Reference Source providing detailed descriptions of places, including maps and geographical facts, generally intended for travelers.

A type of Reference Source, usually in a single volume, containing maps and geographical information, including countries, cities, borders, and roads, but also maps that show topography, bodies of water, climate, crops, population, and so on.

A type of Reference Source similar to a Dictionary, but providing a list of geographical places rather than vocabulary.

A document prepared to describe research, often presented at scholarly conferences, published in Conference Proceedings, or shared in Scholarly Journals.

The research reports or papers describing ongoing research that are presented at a conference which are collected and published, usually as a single volume.

Information sources that are available in more than one format, such as books that are published in print as well as electronically or as audio books.

One of the Formats of Information, which includes audio, such as songs, jingles, or radio; visual, such as infographics, charts, or diagrams; and a combination of the two, such as documentaries, videos, and video games.

A first-hand account of an event, including historical, current, and research events; may include diaries, reports or articles detailing original research, memoirs, photographs, newspaper articles, television reports, or other sources.

A source which reviews or summarizes information from other sources, or in which authors study and analyze past events they did not experience themselves.

A report evaluating, summarizing, and describing information found in research literature such as articles, books, and reports on a topic one is researching, to provide a basis for and guide future research.

An information source intended for researchers and scholars, rather than the general public or professionals as is the case with Popular Sources and Trade Publications; typically written by experts in a field who provide credentials and generally include a list of references.

An information source intended for professionals in a particular field, rather than the general public or scholars as is the case with Popular Sources and Scholarly Publications; typically written by practitioners in a field who occasionally provide credentials. May have references or limited bibliography.

One of the components of the Research Process, which involves the practice of appraising the value of an information source both in its own right and as it relates to your topic, typically by investigating its Authority, Credibility, Currency, Bias, and Documentation.