5 Finding Information

PICKING THE RIGHT SEARCH TOOL(S) FOR YOUR TOPIC

Before you search for information, you need to think about the best place to look. There are several questions you need to ask to pick the best search tool for your topic:

- What are the primary subject areas you are researching? There will usually be more than one. For example, if you are writing a paper on alternative health treatments for ADHD for an education course, you will need to look in education literature, health literature (medicine, nursing, and alternative health databases), and psychology literature. Search tools in each of these fields will provide different perspectives on this topic.

- Are you working on an assignment that requires you to look for specific formats or types of information? Some search tools will find books, but not articles; others will only find articles. Some search tools only index scholarly literature, while others only index popular literature. If there are items you are required to find, or are not allowed to use, be sure the tools you choose include those types of items.

- How lengthy is the required paper? How many sources do you need? For a one-page paper with only one source, using a single database might be sufficient. If it is a 20-page in-depth analysis of a particular issue, you will probably need to look in more places to find more sources.

There are several categories of search tools. In this textbook, we will discuss the following: library catalog, article databases, and library discovery search (OneSearch). These tools can be found on the Stewart Library website. We will also discuss Web search engines.

LIBRARY CATALOG

The library catalog lists items owned by a particular library and its branches. The Stewart Library catalog will locate items owned by the main campus library in Ogden and WSU’s Davis campus library. Most libraries have a link to their catalog from their home page, and anyone with an Internet connection can search the catalog; no login is required.

You can access the Stewart Library catalog by clicking the Catalog button on the Stewart Library’s homepage. The library catalog includes records for items physically housed in the library, including books, CDs, maps, and videos. It shows where they are in the library, and if an item is available for check out.

There are two things you will NOT find in the Stewart Library catalog. The first is electronic resources, such as electronic books and streaming music. These can be found using OneSearch. The second is articles. The Stewart Library catalog will list the titles of the magazines, newspapers, and journals found in the library but will not provide information on the articles. For example, the catalog will tell you that we have copies of the New York Times and Vogue, but it will not provide information on articles in these periodicals. You can find articles on specific topics using article databases or OneSearch.

CALL NUMBERS & LIBRARY CLASSIFICATION SYSTEMS

When you look for information in the Stewart Library catalog, you will notice each item has a call number. Call numbers show you exactly where the item is located in the library.

There are several different classification systems used by libraries, and the call numbers for each look slightly different. The easiest way to tell what type of call number you have is to see whether it starts with a letter or a number. If it begins with a letter, it’s probably the Library of Congress (LC). The LC classification system is used in most academic libraries in the United States. If it starts with a number, it’s most likely a Dewey Decimal system call number. Dewey is used primarily in public and school libraries. There’s another classification system called Superintendent of Documents (SuDocs), used for government documents. These call numbers are distinctive as they often have colons (:) and slashes (/), whereas LC and Dewey do not.

We use all three systems in the Stewart Library.

Library of Congress

Used mostly in academic libraries. Begins with a letter.

Examples:

- LB3621.5.D3 2000

- GV545.52.H64F35 1999

Dewey Decimal

Used in public and school libraries. Begins with a number.

Examples:

- 320.01M645p 1982

- 525.J175j

Superintendent of Documents

Used to classify materials published by the U.S. Government. May have colons (:) and slashes (/).

Examples:

- ED 1.1/3:992

- LC 1.2:AR 7/3/2002

HOW TO READ DEWEY & LC CALL NUMBERS

All numbers in LC are read alpha-numerically. L comes before LA, which comes before LB. LA 1 comes before LA 120, which comes before LA 1000, and so on.

Dewey numbers begin with a number, for example 370.152 STU. The first number (370) is read as a whole number. Treat the rest as a decimal, e.g. 370.152 would come between 370.15 and 370.16. Then work alphabetically to find the letter (S). Sometimes there are numbers after the letter. If this is the case, read these numbers as decimals.

Organization of Dewey Call Numbers

- 370.15 VAN

- 370.152 STU

- 370.16 MCO

- 372.42 SP

- 373.52 IPO

Organization of Library of Congress Call Numbers

- LA1 .P342

- LA120 .H2 P47

- LB247. P38 S6

- LB348. Z48

- LB348. Z56

Dewey Call Numbers

Library of Congress (LC) Call Numbers

WHAT THE CLASSIFICATION SYSTEM MEANS

Call numbers correspond to subjects. If you find a book beginning with the LC call number R, it has something to do with medicine. If you look at call numbers starting with RT, it’s the nursing field. If it has a call number beginning with RK, the book deals with dentistry. Books that start with RK60 deal with preventative dentistry, and books beginning with RK520 deal with orthodontics. This can be useful information. For example, you are doing a paper on operative dentistry and you find the book Sturdevant’s Art and Science of Operative Dentistry, with the call number RK501.A78 2006. You can look right next to it on the shelf at the other RK 501 call numbers to find the Atlas of Operative Dentistry: Preclinical and Clinical Procedures and the book Fundamentals of Operative Dentistry: A Contemporary Approach. In other words, if you can find one great book on your topic, all you have to do is look at the books next to it on the shelf with similar call numbers, and you’ll be able to locate other relevant titles. Remember that books about the history of dentistry could be in another section, such as history, depending on whether the primary subject is considered dentistry or history; one example is Smile Revolution in Eighteenth Century Paris: DC729 .J66 2014.

SUDOCS

There is one more call number system used in the Stewart Library, known as the Superintendent of Documents numbering system which was created for materials published by the U.S. Government. The basis of this system is to group together government publications by author, which is the department or agency that issued the publication. For example, information produced by the Department of Agriculture is found in the A’s, and information produced by the Health and Human Services Department is found in the HE’s.

In the example below, the agency that published this source is the Department of Commerce (C). The subagency is the Census (3), and the series is 186. The report/series number (P-23/) indicates a unique publication within the series, and may consist of numbers or letters and numbers with punctuation. The individual report number (190) differentiates this report from the others in the report series. Punctuation includes colons, periods, slashes and dashes, all of which are separate segments of the call number.

GENERAL/MULTIDISCIPLINARY LIBRARY DATABASES

There are different library databases; some are general or multidisciplinary databases, meaning they cover a wide range of subjects. JSTOR is an example of a general or multidisciplinary database. Subject-specific databases cover a single subject. Art Full Text, Criminal Justice Collection, Education Full Text, and MedlinePlus are examples of subject-specific databases. While JSTOR is a great place to start, it’s best to find a database that focuses on your topic area. To access the databases, click the Databases button on the Stewart Library’s homepage. You can click the link for JSTOR in the Featured Databases sidebar, select a subject from the drop-down Subjects menu for a list of subject-specific databases, or click a letter if you know the database you want to use (databases are listed alphabetically by title).

Stewart Library subscribes to over 250 databases on a wide variety of topics. It is often a good idea to use both general and subject-specific databases. For example, if you are doing a paper on alternative health treatments for diabetes, it would be a good idea to use a general database plus a variety of health-related databases, such as Consumer Health Database (popular and scholarly articles on health care topics), MedLinePlus (scholarly articles from all fields of medicine), CINAHL (popular and scholarly articles in nursing, allied health, biomedical and consumer health literature), and Health & Medical Collection (scholarly full-text articles in the health professions).

Some databases only include articles from periodicals (magazines, newspapers, and journals) or entries from reference books (encyclopedia articles or dictionary entries). Others only include collections of images, pamphlets or brochures, legal proceedings, chemical structure, case studies, or specific reports, such as U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission filings or papers presented at conferences. Some databases include a variety of different sources. It is important to look at the type of information covered in a particular database before you search. At WSU, brief descriptions of the databases are found in the lists of article databases on the Stewart Library website. For example, if you look at the three database descriptions below, you’ll see that the Newswires database includes world-wide newsfeeds. This would not be a good database for someone who needs scholarly articles.

The IEEE Xplore database includes journals, magazines, conference proceedings, and standards in engineering, computer science and other related disciplines.

The Academic Video Online (AVON) is a huge database of videos; again, if one needed articles on topics, this would not be the best place to look.

HELPFUL RESOURCE VIDEOS

Helpful videos are located on the Library Science (LIBS) Textbooks and Resources webpage in the “Videos – How to Use Library Resources” section. These videos provide a quick overview of using a few of our general/multidisciplinary databases and services. A few of these videos are linked below.

- CQ Researcher and Global Issues in Context are great databases for pro/con or argumentative papers on various current issues.

- ProQuest Central is our biggest multi-disciplinary database, covering nearly every area of academic study. This database includes popular magazines, trade publications, and scholarly publications.

- The Stewart Library provides full text access to over 150,000 eBooks covering multiple subject areas and topics. Learn about searching for eBooks.

- The Stewart Library subscribes to over 250 databases. Learn about Selecting a Database.

- Interlibrary Loan is an excellent resource for requesting any materials located outside of the Stewart Library Collections.

COMMON CITATION MISTAKES WHEN USING DATABASES

When citing sources, some find it a little confusing to parse database records and find specific pieces of information, such as database names, journal titles, publishers, and other items commonly found in database records. To help clarify some of these common mistakes, please review Dissecting Database Records in Chapter 8: Citing Sources.

ONESEARCH

OneSearch is a discovery tool — sort of like a “library Google search.” It provides a single gateway to the Stewart Library’s extensive collection, including books and e-books, articles, streaming music, videos, dissertations and theses, conference proceedings, government documents, and digitized sources from WSU Archives and Special Collections. It also searches most journal, magazine, and newspaper resources available through the article databases. Other types of materials such as library research guides are also included. If you wanted to find everything in one place, OneSearch would be the best place to look. The main drawback to OneSearch is that you will typically get a lot more than you need, which can be overwhelming; you must be able to do specific searches and limit your results.

To use OneSearch, enter your search statement in the search bar located on the Stewart Library’s homepage. OneSearch is best for lower level research like English 2010, Botany 1303, or History 1700, or for research where an interdisciplinary or multidisciplinary approach is needed.

Anyone can access and search the OneSearch interface and Stewart Library resources; however, only Weber State University-affiliated patrons can access licensed resources (such as articles and other resources in the library’s article databases). These resources require you to log in using your WSU username and password.

While it does contain information from most of the library’s databases, some information is unavailable in OneSearch. If you are doing more advanced work, figure out the best databases in your field and use them directly. Individual databases will always allow you to focus your search better than OneSearch. However, if you’d like to use OneSearch for advanced research, you can use some advanced search features.

WEB SEARCH ENGINES

There are numerous general Web search engines, such as Bing, Yahoo, and DuckDuckGo. The most well-known engine is Google, because it is more sophisticated than others. Not all search engines function like Google, and different search engines yield varying results due to their ranking methodologies.

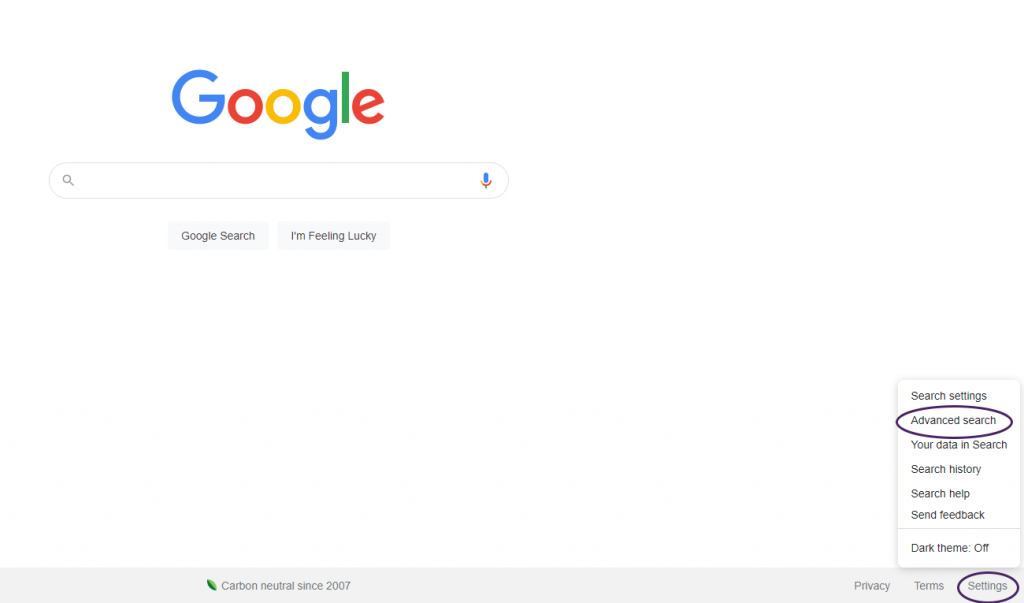

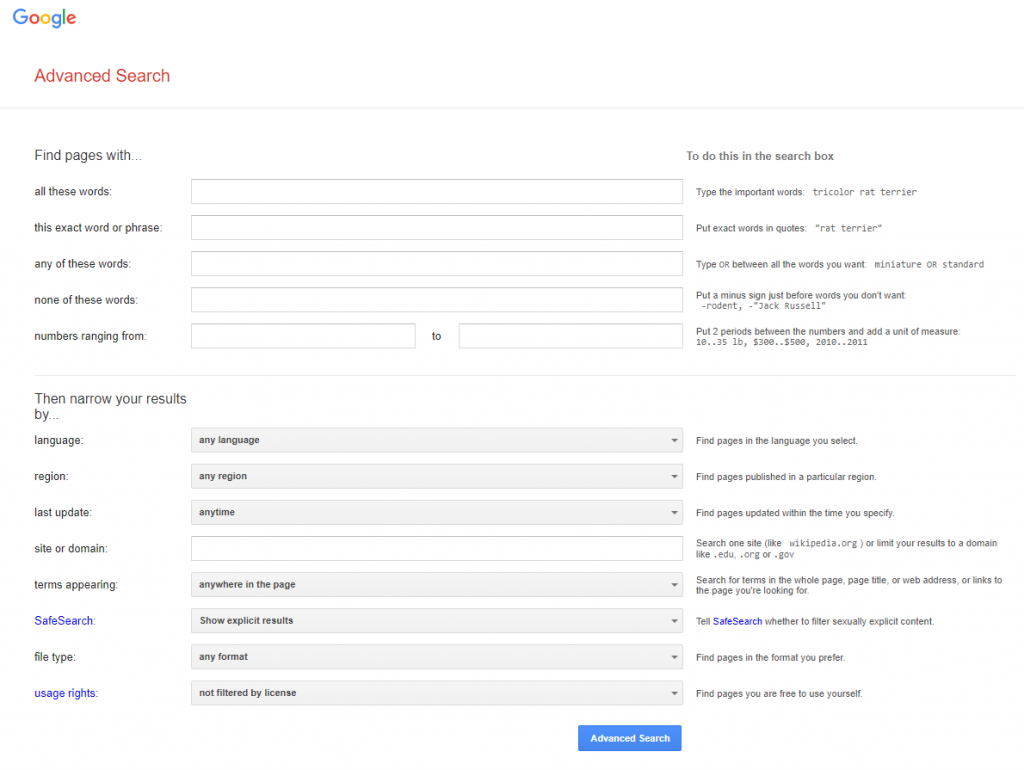

Google allows you to limit your search in many ways, for example, by domain (.edu, .gov, .org). One way to limit your search is to use the Advanced Search screen, which at the time this screenshot was taken, was accessible from the settings menu located in the lower right-hand corner of the Google search screen. (Google is famous for making changes to its interface, so it may have moved.) You can also access Advanced Search through Settings under the search bar on the results page after conducting an initial search, which is useful if your browser gives you a Google search option without taking you to the Google search page, such as Chrome does. Once you are in the Advanced Search screen, you can limit by language, file type, and usage rights, to name a few (see following images).

To more effectively search using Google’s basic search box, use these tips:

- Whenever you have a phrase, like “gun control,” “stem cell research,” or “global warming,” ALWAYS use quotation marks. This will reduce the number of results you retrieve significantly and increase the relevancy of your results.

- Unlike article databases, the order of search terms affects the search results in Google. Be sure to put the most important terms first.

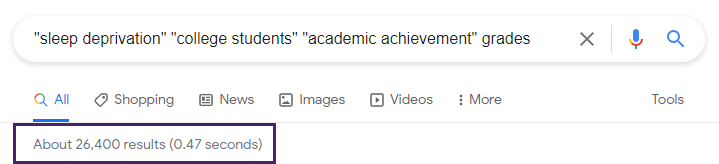

- For more relevant results, use more terms. For example, if you are interested in how sleep deprivation affects college students’ grades, don’t type “sleep deprivation” in the box. Instead, type “sleep deprivation,” “college students,” and “academic achievement.”

The following pages show the results using different terms.

This search on sleep deprivation retrieved over 58 million hits. Unfortunately, the top search results did not provide information on sleep deprivation, specifically in college.

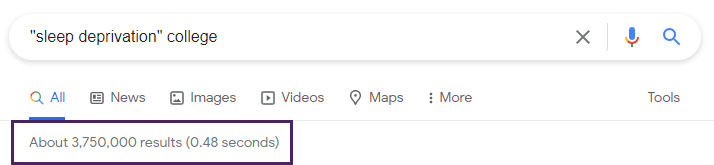

This search retrieved fewer results but still provided over 3 million hits.

Putting “sleep deprivation” in quotation marks and adding the word college helped lower the number of results and made the results more relevant. All the results have something to do with sleep deprivation in college, but only some address grades or academic achievement.

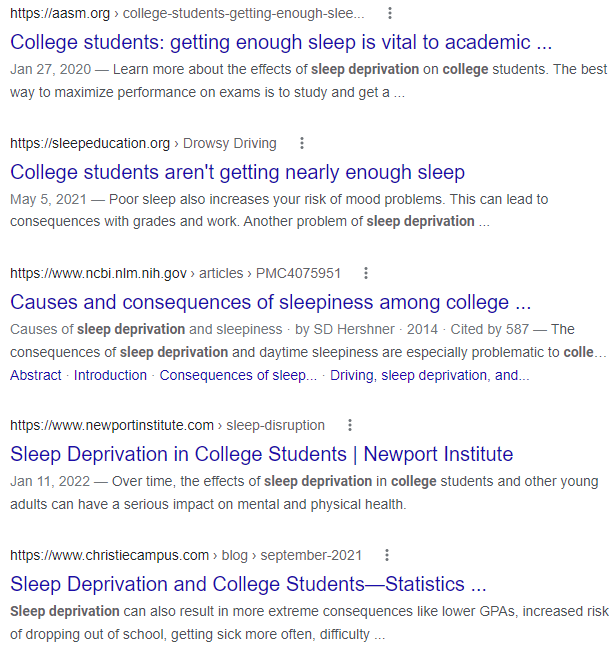

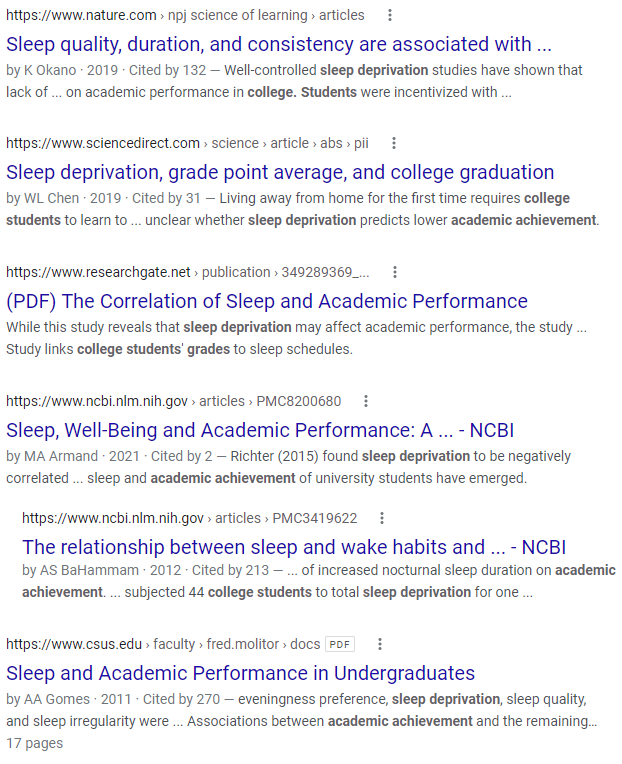

This search retrieved only 26,400 results.

Using quotation marks around all the phrases and adding a few more relevant terms decreased the number of results. A few of these sites focus on grades, sleep deprivation, and college students.

INTERPRETING YOUR RESULTS

After you do a Google search, how do you know what you found? Is it a book? An article? A website or webpage? A blog? A report? What can you guess about the sources from looking at the results? You can save time by evaluating your search results BEFORE you click on them.

Here is a Google search results screen for a search on test anxiety in college students and an initial examination of this page. These search results include scholarly articles, commercial websites, education websites, and organization websites. One link takes you directly to a PDF source.

Note: Google and the Google logo are trademarks of Google LLC.

Many Google Scholar searches retrieve online scholarly journal articles. Below is an example of what a journal article might look like online. Online articles typically have a volume number, issue number, and journal title. Many will also include an abstract/summary of the article’s content. (More on searching Google Scholar is covered in the next section.)

The following example is a non-scholarly website article post found in a Google search. This article is located on a .org website for California Community Colleges, California Virtual Campus Online Network of Educators. When reading through this article, you will see in-text links to surveys and other sources. Online articles may or may not include a formal Works Cited or Reference list.

The source below (a website homepage) is typical of something you might find in a Google search. This website provides Online Student Readiness Tutorials from the California Community Colleges Online Education Initiative. This website homepage links to several online resources that are available for students.

Within the California Community Colleges Online Education Initiative Online Student Readiness Tutorials website are webpages focusing on various student success topics. The example below features the webpage for Personal Support.

GOOGLE SCHOLAR

The Google Scholar search engine provides an easy way to search for scholarly literature digitally. While Google retrieves any website (both good and poor quality), Google Scholar weeds out general websites, linking you to some of the scholarly sources you would see in article databases like Biological Abstracts, JSTOR, or ProQuest Central. Google Scholar includes various scholarly materials including articles, preprints, theses, books, technical reports, etc. These materials come from multiple sources, including academic publishers, professional societies, and universities. Even if you find something through Google Scholar instead of Google, you should evaluate any source before you use it.

Q. Is the material on Google Scholar the same as in the library’s databases? (In other words, is it better to use one over the other?)

A. Not always. If you want to do a more comprehensive search, use library databases in addition to Google Scholar. While there is some overlap between the two, there are some significant differences. This table illustrates these differences:

| GOOGLE SCHOLAR | LIBRARY DATABASES | |

|---|---|---|

| ACCESS | Anyone with an Internet connection can access it, but users affiliated with universities may be able to access more full-text materials | Users must generally be affiliated with an academic or public library to access |

| FOCUS | The focus is on scholarly sources like journal articles, especially in science and technology, but it is not the best source for popular information | Provide both scholarly and popular sources of information on a wide variety of topics |

| SEARCH OPTIONS | Basic keyword/phrase searching with few advanced search features; supports natural language searching | Databases allow more sophisticated options for customized searches and more relevant results based on available filters or limiters |

| RESULTS | It can be sorted by relevance, which may pull up older results first; can also sort by date | It can be sorted in several different ways |

| SOURCES | Full list is not provided by Google, but does include scholarly journal publishers and universities | Each article database has a specific source list |

| FULL TEXT | Some documents are freely available to anyone, some require university affiliation, and some are not available without payment. Note: Look for Full-Text @ My Library links to the right of article titles. These are set up on campus; to set up at home, click the menu icon in the top left, select Settings, then Library Links. | Many databases provide full-text, and Interlibrary Loan service can freely obtain items not available in full-text at the library or online |

| ARTICLE VERSIONS | Groups different versions of the same article together, including versions written prior to publication | Provides the official published version of the article |

SEARCHING GOOGLE SCHOLAR

Sometimes, when searching Google Scholar, you will find interesting article citations or abstracts (summaries). In many cases you may have access to the full text of these articles through the Stewart Library. By setting “Library Links” to specify items in the Stewart Library, Google Scholar will show you which items are full text. Articles that cannot be obtained through full text via Google Scholar can be found through Interlibrary Loan.

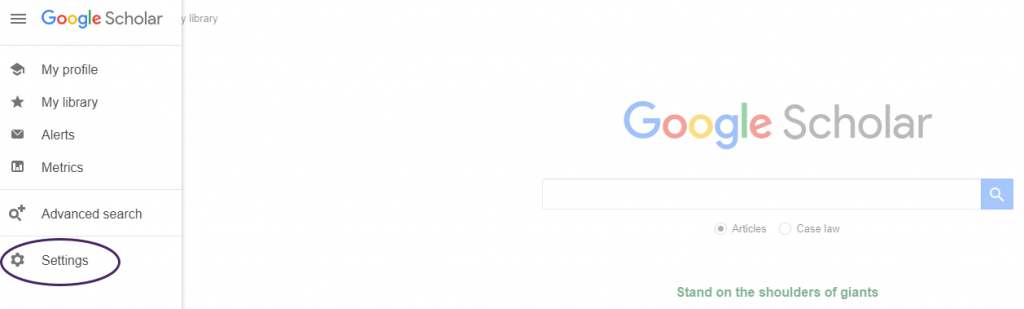

To link to Stewart Library resources, locate the three lines at the top left-hand side of the Google Scholar website. When you click on those three lines, a menu will appear. Click on “Settings.”

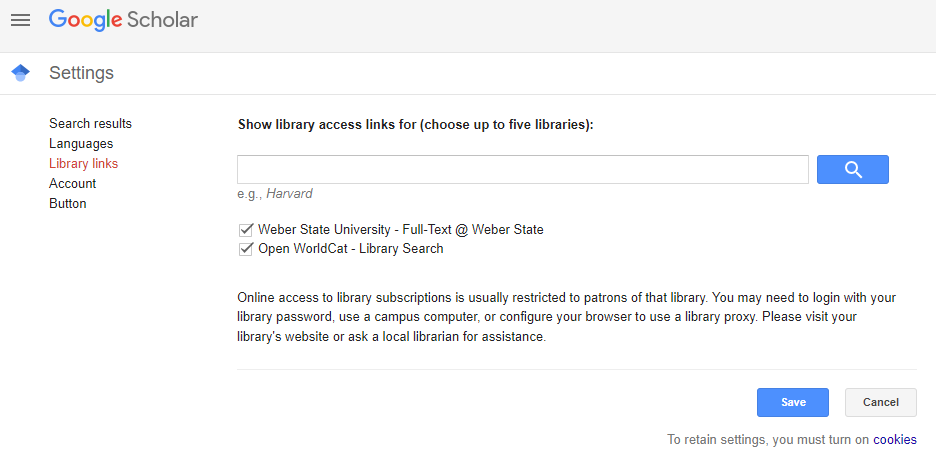

On the Settings screen, click on “Library Links.” Type “Weber State University” in the search box. Check all of the options that appear in your search. Click “Save.”

Video tutorial on how to link Google Scholar to Stewart Library resources.

Note: Google and the Google logo are trademarks of Google LLC.

As with any Google search, it is a good idea to examine the results screen and make some initial judgements about what you find. Google Scholar tends to find more scholarly articles than anything, but you may also see websites, webpages, or books. However, not all of them will be available in full-text directly from the results screen.

WIKIPEDIA

There are many kinds of wikis. Some are general, and some focus on very narrow subjects. Wikipedia is probably the most well-known Wiki. It includes a collection of articles on every topic imaginable and is written and edited by volunteers. Your instructors may have told you it’s a horrible place to get information. This is not completely true; if you carefully evaluate the content, Wikipedia can be a useful place to look for topics, get useful background and keywords for library search tools, and find references and sources, especially Web sources. Like other encyclopedias, you can use Wikipedia for basic research, facts and figures, and background information. You’ll need to pay closer attention to the quality of the article than in a regular encyclopedia. In a regular encyclopedia, editors check the articles; in Wikipedia, you must evaluate the article. (While Wikipedia does have editors, it is much more difficult for them to keep up with everything.) Remember, while it can be helpful for background information, many instructors will not allow you to use Wikipedia as one of your sources.

Signs of a quality Wikipedia article:

- It agrees with other information you’ve found from accurate and authoritative sources.

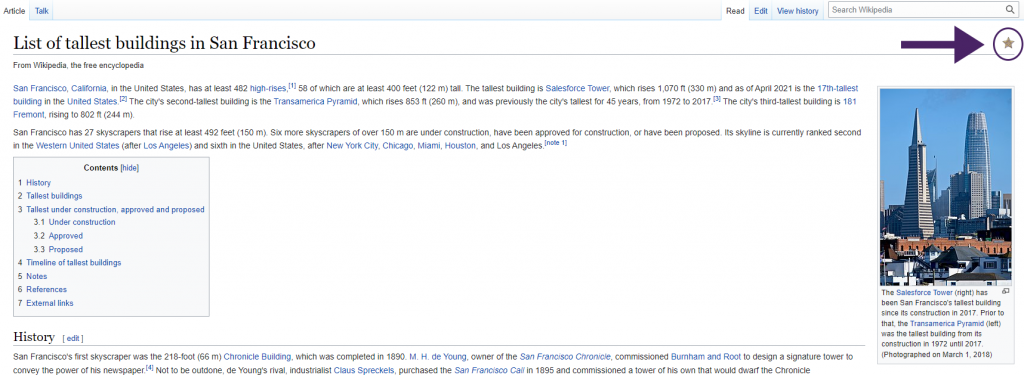

- It was a featured article (checked by Wikipedia editors and indicated by a small star in the upper right corner).

Note: From Wikipedia, 2022. CC BY-SA 3.0. - It has a good list of references and external links. There should be a variety of sources on the reference list, except for specialized subjects, the use of just one or two sources means the author didn’t do their homework.

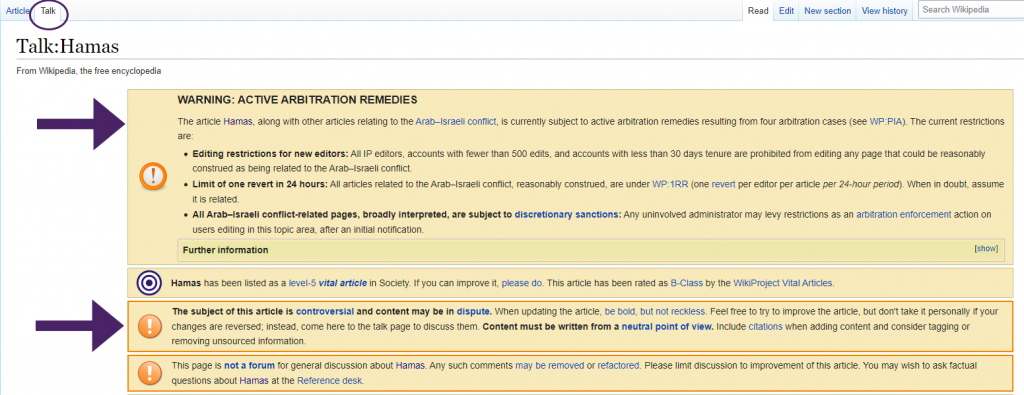

- Check out the discussion by clicking on the Talk tab. There are often clues to the quality of the article in the discussion surrounding it. In general, if you see low ratings, arguments, or users disagreeing, be careful about using the article.

Note: From Wikipedia, 2022. CC BY-SA 3.0. - If there’s a banner across the top or within the article, this is a clue you may need to avoid using the article. Banners usually say something like: “The neutrality of this article is disputed” (Wikipedia articles are supposed to be neutral, not support one side or another). A banner might also point out that the article lacks references or citations or doesn’t meet Wikipedia’s quality standards.

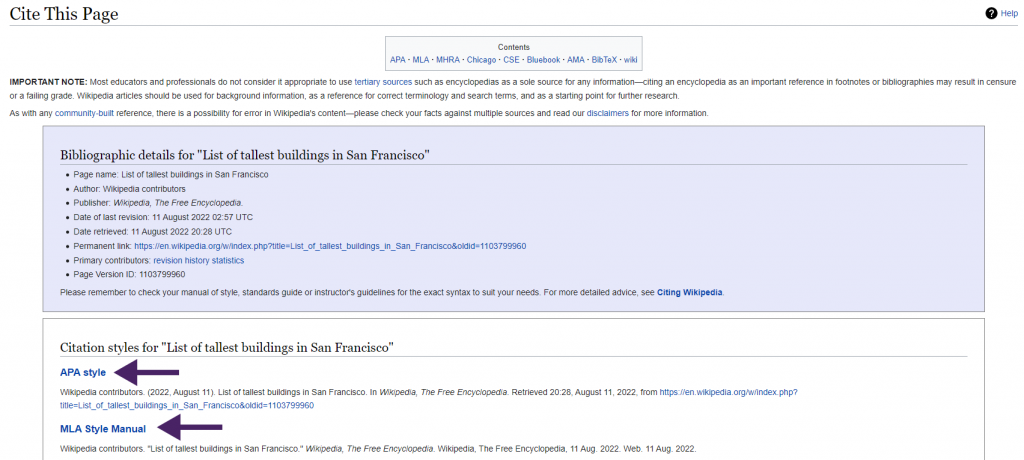

Wikipedia has a helpful “Cite this page” feature.

On the Cite page, scroll down until you see APA or MLA. Please keep in mind that these citations may not be entirely correct. Consult the official APA or MLA manual for specific instructions on how to cite online sources. Citation information is provided for the article in case you want to write your own citation or use a different citation style.

USING THE WEB VS. USING LIBRARY SEARCH TOOLS

Choosing the right tool for the job is not always easy, and as this chapter previously mentioned, the tool you use depends on the topic and the types and amounts of information needed. In general, it is a good idea to use library tools in conjunction with the Web. Most people like Google because it is easier and more convenient to search — Google does not require ANDs and ORs and special symbols — and one can type in an entire question as you would ask it to another person. A simple search will often retrieve millions of results. While they sometimes require you to formulate search statements, choose keywords, and use special symbols, library tools usually concentrate on specific information formats or subject areas. It is typically easier to focus a search in a database, and one can choose databases that index certain types of information.

Beware of the common misconception that library search tools only include “scholarly stuff.” While some do, most include both scholarly and popular information. For this reason, it is critical to examine a source and make an educated judgement about the quality of that source regardless of where you find it. Evaluating information quality is covered in Chapter 6: Critically Evaluating Information.

Traditionally a written or printed work consisting of pages glued or sewn together along one side and bound in covers, also available in audio, electronic, and braille formats, making it both a Multi-Format Information source and one of the Long Formats of information.

An information source intended for researchers and scholars, rather than the general public or professionals as is the case with Popular Sources and Trade Publications; typically written by experts in a field who provide credentials and generally include a list of references.

An information source intended for the general public, rather than professionals or scholars in a particular field as is the case with Trade Publications and Scholarly Sources; typically written by journalists or other authors who do not provide credentials; generally, they do not include a list of references.

A Library Search Tool that provides access to results within the Catalog and many Library Databases.

An interface for a computer program hosted on a website that indexes information and allows Internet users to search through online content, generally using Natural Language Queries, and which typically returns results that include Websites and Webpages.

A Library Search Tool where information about the library’s book collection is kept and made searchable, to allow users to discover and locate needed information

A type of Periodical, containing articles, illustrations, and advertisements, and sometimes covering a particular subject or area such as hobbies, popular culture, or parenting. Typically a Popular Source.

A type of Periodical, containing articles and some photographs and advertisements. Often specific to a city or region; sometimes covering a particular subject or area such as business or finance. Typically a Popular Source.

A single publication with new issues published on a regularly scheduled basis, such as daily, weekly, monthly, or quarterly, and generally including Newspapers, Magazines, and Scholarly Journals.

A symbol or code on an item, such as a book, that indicates its location in the library, and is often incorporated in the items catalog record.

A hierarchical structure that forms the basis for the organization of a collection, particularly a library, including Library of Congress Classification, Dewey Decimal Classification, and Superintendent of Documents Classification.

The official library serving the United States Congress and the largest library in the world. Also holds the US Copyright Office, and is tasked with collecting and preserving materials pertinent to US history.

The Classification System used by the Library of Congress to catalog and organize the collection, using an alphanumeric code, with letter pairs and a number 0 through 9999, to represent subject areas; also used by many colleges, universities, and other holders of large multi-subject collections.

A Classification System developed by Melville Dewey in 1876 that uses the numbers 0 through 999 to categorize information, and a decimal followed by additional alphanumeric codes for subcategories; generally used to organize K-12 school library collections and some public library collections.

The Classification System used by libraries to catalog and organize documents published by the United States Government, first by the responsible department or agency, then sub-agency, series number, report/series number, and individual report number.

An electronic collection of information resources, generally including periodical articles, books, and audio-visual material, to which the library subscribes through the services of database vendors.

A type of Reference Source that provides information about topics in a comprehensive, but summary fashion, like an overview. They are useful for providing facts and giving a broad survey of a topic, and are often written by specialists.

A type of Reference Source which defines words, illustrates pronunciation, describes etymology (word history or origin) and usage, and lists synonyms and antonyms.

A pamphlet or booklet, particularly one containing descriptive information and pictures of a product or service. One of the Long Formats of information.

Giving credit to authors of whose works are used to inform new works, often by Summarizing, Paraphrasing, or Quoting, and providing Attribution, thereby informing readers of where the information came from.

The research reports or papers describing ongoing research that are presented at a conference which are collected and published, usually as a single volume.

One the most commonly used Web Search Engines, used widely to search for information on millions of topics. Also used as a verb, meaning to use a Web Search Engine to search for information.

A small group of words standing together to represent a concept or name of a place, person, or thing, such as United States, Rosa Parks, or air conditioner, used in Phrase Searching.

A collection of information hosted online with a common URL, usually found by searching a Web Search Engine or navigating directly to a known URL, and generally made up of several related Webpages and organized by the inclusion of a menu linking the pages together.

One of the Long Formats of information: a part of a larger Website, usually linked to by a menu or table of contents on the main page (or homepage), like a page in a Book.

A regularly updated website or web page written in an informal or conversational style, usually by one person or a small group of contributors; short for “Web Log.” One of the Long Formats of information.

A Web Search Engine designed and operated by the Google company to filter general websites out of results, and retrieve scholarly sources such as articles, books, theses, preprints, and technical reports.

A type of Periodical containing articles written by experts in specific disciplines, often Peer Reviewed.

A Long Format of information, created online but similar to an Encyclopedia in format and content (either general or topic-specific) but editable by users.

A Wiki open to and editable by the public, with very broad topic coverage, that can be a useful tool for the beginning stages of the Research Process, such as choosing a topic or finding Keywords, but which is generally not considered to have sufficient Credibility to be used as a source for college-level research

A main idea or important word in a research question or thesis statement; two or more keywords can be combined with Boolean Operators to form the Search Statements used to locate sources in Library Search Tools.

An electronic search tool, such as a Library Catalog or Library Database, for discovering, locating, and/or accessing print or electronic library materials, similar to a Web Search Engine, but specific to library resources and often proprietary in nature.

A Boolean Operator used to combine Keywords into Search Statements, limiting search results to only items including all of the specified search terms.

A Boolean Operator used to combine Keywords into Search Statements, enclosed in parentheses that will retrieve results including any of the specified search terms, but not necessarily all of the search terms.

A specially formulated query, which combines Keywords, Phrases, Truncation, and Boolean Operators with specific punctuation, used to locate resources within a Library Search Tool.