Testing the Efficacy of Leadership for Empowerment and Abuse Prevention (LEAP), a Healthy Relationship Training Intervention for People with Intellectual Disability

Parthenia Dinora; Seb Prohn; Elizabeth P. Cramer; Molly Dellinger-Wray; Caitlin Mayton; and Allison D'Aguiliar

Dinora, P., Prohn, S., Cramer, E., Dellinger-Wray, M., Mayton, C., & D’Aguiliar, A. (2021). Testing the Efficacy of Leadership for Empowerment and Abuse Prevention (LEAP), a Healthy Relationship Training Intervention for People with Intellectual Disability. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 2(1), 19.

Testing the Efficacy of Leadership for Empowerment and Abuse Prevention (LEAP) PDF File

Abstract

Leadership for Empowerment and Abuse Prevention (LEAP) is an abuse prevention intervention for people with intellectual disability. The purpose of this research was to evaluate the intervention’s efficacy. Findings indicated no significant differences in scenario identification questions depicting acceptable or concerning situations. However, statistically significant improvements were noted in participants’ depth of understanding, including their ability to correctly describe why a scenario was abusive or exploitative and what to do next when confronted with unhealthy situations. Limitations and implications for practice are discussed.

Plain Language Summary

LEAP is a training program for people to help them have good relationships. We did research to see if LEAP helped people who came to training better tell the difference between good and bad relationships and what to do if they are in a bad relationship. We found that people did not get better at pointing out good and bad relationships, but they did get better at telling why a relationship was good or bad and what to do next if in a bad situation.

Background

The risk of abuse against people with disabilities, particularly people with intellectual disability (ID), has been well documented in the literature (Curtiss & Kammes, 2020; Harrell, 2012; K. Hughes et al., 2012). Abuse of people with ID often begins in childhood and continues throughout the lifespan (Catani & Sossalla, 2015). In a systematic review, Byrne (2018) cited abuse prevalence rates ranging from 14% to 32% for children and 7% to 34% for adults with ID.

Compared to people without disabilities and other disability groups, people with ID are at an increased risk of targeted violence and are more likely to experience abuse, neglect, and exploitation (Beadle‐Brown et al., 2010; Office of Justice Programs, 2018; Smith et al., 2017). The majority of abuse perpetrators are known by and may be familiar to the person with ID and can include parents, intimate partners, extended family members, teachers, transportation drivers, and paid service providers (Harrell, 2017; Stevens, 2012). Victims with disabilities do not always seek help, but when they do, they often face barriers including, inaccessible structures, programs, and service providers who are unequipped to work effectively with them and provide care (Malley, 2020; National Child Traumatic Stress Network [NCTSN], 2016). As a high-risk population that has been underserved in their communities, adults with ID would benefit from abuse prevention programming that is empirically validated and targeted to their specific needs (Bowen & Swift, 2019; Eastgate et al., 2011; Hickson & Khemka, 2016).

Evidence-Based Abuse Prevention Programs for People with Intellectual Disabilities

Over the past 15 years, there has been an increase in abuse prevention programs for people with ID with varying formats and types of evaluation. Systematic and scoping literature reviews of studies of abuse prevention programs for adults with ID show, however, that the majority of the programs focus on women with mild to moderate ID (Araten-Bergman & Bigby, 2020; Doughty & Kane, 2010; Lund, 2011; Mikton et al., 2014). Most programs are based on a theoretical framework, such as the social-ecological model, and incorporate skill development to increase participants’ ability to respond to abuse. These programs are characterized by verbal and textual learning methods and utilize cognitive, behavioral, or psychoeducational-based curricula. Many of the curricula address physical, sexual, and emotional abuse in addition to intimate partner, familial, and non-familial abuse. Most of the training sessions are held in person and led by trainers who do not identify as having a disability. Few programs involved people with disabilities, including those with ID, in their development. The literature generally lacks information on how programs are tailored to participants’ needs. For example, how participants communicate, their support needs, and how curriculum components are adapted to the learning styles of participants. Additionally, participants’ sociodemographics are largely missing except for ID category (mild, moderate, severe) and gender (Araten-Bergman & Bigby, 2020; Doughty & Kane, 2010; Lund, 2011; Mikton et al., 2014).

The evaluation designs in the literature cited above include satisfaction surveys, pre-post evaluations, and randomized control trials. The majority of the reviewed studies utilized a pre-post research design, and most did not include a qualitative component. Participant outcomes were typically assessed using self-reported questionnaires, and specific measures varied across studies. Most of the studies did not use a measure of incidents or frequency of abuse, and our review of previous studies indicated that only a few of the programs included implementation fidelity protocols (Hickson et al., 2015; R. B. Hughes et al., 2020; Ward et al., 2012). Efforts to empirically validate abuse prevention programs for adults with ID pose difficulty because of the heterogeneity of the study population and challenges with the development of instrumentation and study processes that meet the comprehension needs of people with ID and allow for their full participation in research (Dryden et al., 2017; Kidney & McDonald, 2014). The small number of rigorously evaluated programs, along with the variation in outcomes measured across studies, has made it challenging to establish best practices in abuse prevention programming for this population (Araten-Bergman & Bigby, 2020; Doughty & Kane, 2010; Fisher et al., 2016; Mikton et al., 2014).

Within the body of literature on abuse prevention programs for people with ID, studies are lacking in several ways. Few programs are led or co-led by people with disabilities or include men. Also, little appears in the literature about program implementation fidelity or curricula that incorporate multimodal teaching strategies. Finally, many existing programs do not address varying support needs, especially within the context of research processes and instrumentation. To address some of the limitations of existing programs and research designs, and to best meet the needs of people with ID in our locale, the authors developed, implemented, and evaluated Leadership for Empowerment and Abuse Prevention (LEAP), an abuse prevention program for people with mild, moderate, and severe ID. LEAP utilizes multimodal teaching and learning strategies, including adaptations for people who communicate through nonverbal means and is co-led by people with disabilities. The evaluation design incorporates video-based assessments to address the limitations of text-based questionnaires and includes an implementation fidelity process and measure.

Theoretical Framework for LEAP

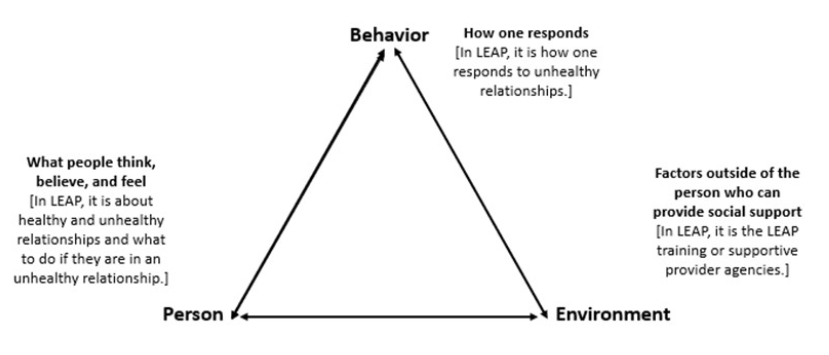

This research aimed to test the efficacy of LEAP, an abuse prevention educational intervention for people with ID. The development of LEAP was informed by Social Cognitive Theory (SCT; Bandura, 1986, 1997). SCT describes how people acquire and maintain certain behavioral patterns and asserts that behavioral change depends on the interplay among the environment (i.e., the external world), people (i.e., beliefs, ideas, and feelings), and behavior (i.e., how people act). Figure 1 illustrates the SCT conceptual framework and its application to LEAP.

Figure 1 LEAP Conceptual Framework

Figure 1 LEAP Conceptual FrameworkAccording to SCT, people acquire skills and new behaviors by acting them out, being reinforced for their actions, and observing others. These direct and observed experiences influence behavior through expectations they create, including expectations about the ability to perform the behavior successfully and the consequences of the behavior (Bandura, 1986, 1997).

With SCT in mind, the LEAP intervention relies on vignette scenarios, role-playing, and group exercises for instruction. Participants learn by observing and discussing modeled behavior. LEAP is designed to strengthen participants’ self-efficacy and self-confidence and is reinforced by a repeated empowerment statement.

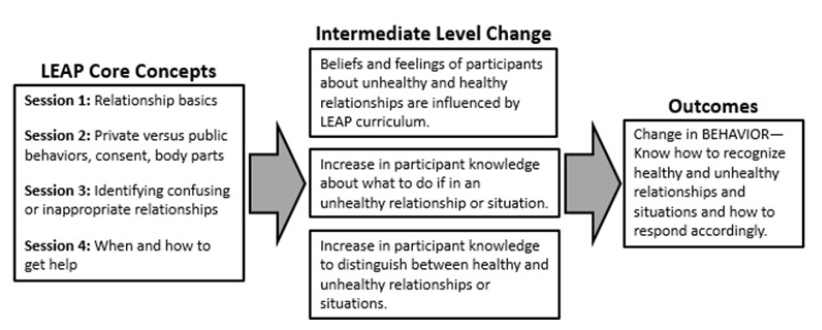

The curriculum’s theory of change (Figure 2) is focused on learning to differentiate between “healthy” and “unhealthy” relationships/situations, knowing how unhealthy relationships may lead to abuse, and how to respond when in an unhealthy relationship/situation. Accordingly, the curriculum targets a person’s knowledge, feelings, and beliefs to influence behavioral outcomes.

Figure 2 LEAP Theory of Change

Figure 2 LEAP Theory of ChangeLEAP Research Questions

Although awareness, prevention, and intervention programs have been developed to address the risks that people with ID face, there continues to be a need for quality research to demonstrate meaningful participant outcomes (Hughes et al., 2020; Mikton et al., 2014). Our research study addressed this gap by testing the efficacy of the LEAP healthy relationship intervention for people with ID. Research questions included the following.

- Do LEAP participants increase their knowledge about healthy and unhealthy relationships after completion of the intervention?

- Do LEAP participants better (a) distinguish between healthy and unhealthy relationships, (b) explain why they made their determination, and (c) identify a next step if the relationship is unhealthy after the completion of the intervention?

Method

All methods were reviewed and approved by the supporting university’s Institutional Review Board.

Setting and Recruitment

This study used primarily quantitative methods to determine the effectiveness of the LEAP intervention using availability (purposive) sampling procedures. Research participants were recruited from 15 residential and community-based disability agencies providing day support and employment services to adults with ID in one Mid-Atlantic state. Participants in the study included adults diagnosed with ID who regularly attended the agency, were interested in participating in the LEAP intervention, and completed the consent process. Participating agencies agreed to provide space for the consent process, pretest and posttest, and four 90-minute weekly LEAP sessions. Eligibility for the LEAP study included the following criteria for participants: (1) must be between the ages 18-65 years; (2) identified as having an ID by a service provider, legal guardian, or family member; (3) ability to demonstrate an understanding of the study description and risks; and (4) ability to provide informed assent or consent. Consent and assent for research were secured from participants and legal guardians, as required.

Participants

All 109 LEAP participants were recruited from organizations and providers that specialized in serving people with ID. A representative from these organizations used administrative records to report the personal characteristics of study participants. Sample characteristics, including age, gender, race, level of ID, guardianship, and residence type, are reported in Table 1.

| Characteristic | M | SD | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 34.3 | 13.5 | ||

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 56 | 51.4 | ||

| Male | 52 | 47.7 | ||

| Missing | 1 | 0.9 | ||

| Race | ||||

| African-American | 32 | 45.7 | ||

| Asian | 3 | 2.8 | ||

| Hispanic | 1 | 0.9 | ||

| White | 31 | 44.3 | ||

| Two or more races | 5 | 4.6 | ||

| Missing | 3 | 2.8 | ||

| Level of intellectual disability | ||||

| Mild | 49 | 45 | ||

| Moderate | 33 | 30.3 | ||

| Severe | 3 | 2.8 | ||

| Unspecified | 24 | 22 | ||

| Have guardian | ||||

| Yes | 35 | 32.1 | ||

| No | 74 | 67.9 | ||

| Residence type | ||||

| Independent home or apt. | 9 | 8.3 | ||

| Parent or relative’s home | 57 | 52.3 | ||

| Host/sponsored home | 8 | 7.3 | ||

| Agency 1-2 residents | 2 | 1.8 | ||

| Agency 3-6 residents | 29 | 26.6 | ||

| Agency 7-12 | 4 | 3.7 | ||

Participants’ age ranged from 18 years to 65 years. Slightly more than half of the sample were women, and most were either African American (46%) or White (44%). Two-thirds of participants did not have legal guardians. More than half lived at home with a parent or relative, and 30% lived in a group home.

Several administrative records on program participants contained incomplete information. As a result, 22% of the sample had an unspecified level of ID. Most participants had a “mild” ID label, an additional 30% had a “moderate” label. Only three participants were described as having “severe” ID.

LEAP Intervention

The LEAP intervention is four sessions that are approximately 1½ hours each. The curriculum focuses on teaching key concepts of healthy relationships, a widely accepted primary intervention for abuse prevention (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2018; Foshee et al., 2004; Ward et al., 2013; Wolfe et al., 2009). It was developed by a team of adults with disabilities, family members, disability support providers, and professionals from health, domestic violence, child advocacy, and social services.

LEAP provides introductory information and supports taking action to identify and avoid potentially unhealthy relationships. Each session reinforces the concepts taught in the previous session and reiterates an empowering statement, “I am strong. My feelings are important. I deserve to feel safe. I deserve respect.” Table 2 outlines each LEAP training session and the key concepts discussed during the sessions. The multimodal curriculum uses different teaching strategies outlined in Universal Design for Learning, such as visual, auditory, kinesthetic, and tactile, along with behaviorally based instructional approaches including prompting, rehearsal, reinforcement, and role-plays (CAST, 2015; Parsons et al., 2012; Rapp, 2014). The LEAP intervention also reinforces ideas and concepts through consistent repetition, which has been shown to increase comprehension for people with ID (Archer & Hughes, 2010).

| Sessions | Summary of session content |

|---|---|

| Session 1: Relationship basics |

|

| Session 2: Private versus public behaviors, consent, body parts |

|

| Session 3: Identifying confusing or inappropriate relationships |

|

| Session 4: When and how to get help |

|

A LEAP Implementation Manual (How-To Guide for Trainers) complemented the curriculum and established trainer preparation and fidelity protocols. The guide provided scripts, specific instructions for delivering the training, suggestions for participant engagement, and described the main points to emphasize in each session. The LEAP manual supported fidelity of implementation across 15 sites and 12 trainers. A unique feature of the LEAP program is a training approach that includes two trainers, one person who has a disability and one who does not. The peer trainer modality is designed to promote positive role models regarding healthy relationships and abuse prevention and answer questions based on lived experience.

As part of their preparation, trainers are instructed by violence prevention experts on how to respond when participants reported that they are or have been victims of abuse. In the development of the curriculum and the training of trainers, it was essential to consult with experts to ensure that appropriate actions were taken in the event of a participant’s disclosure of an abusive experience.

Measures

LEAP measures were focused on two areas: (1) developing protocols and monitoring tools to assess trainer fidelity of implementation and (2) evaluating participant outcomes.

Implementation Fidelity

The trainer fidelity of implementation protocol adapted a four-step process developed by Fixsen et al. (2005), which included: (1) identifying the critical components of LEAP; (2) identifying implementation steps and processes that trainers must follow when presenting the curriculum to participants; (3) developing an observational protocol that reflects these instructional steps and processes; and (4) testing and refining the protocol to examine feasibility, usability, and reliability across observers. This process resulted in an implementation fidelity checklist for each LEAP training session completed by a third-party observer trained in LEAP protocols. The checklists included items on room arrangement, time management, co-trainers’ use of required facilitation strategies, participant engagement, required content for each session, and a review of the main points of each module. Over four sessions, there were a total of 208 items in the fidelity checklists.

Video Vignette-Based Pre-Post Measures

Video vignette pre-post measures were developed using a research-based process (see Dinora et al., 2020; Martinez et al., 2014; Oremus et al., 2016; Stacey et al., 2014) and included a hypothetical story for the participants to evaluate. Vignettes were scripted based on the curriculum’s core components (see Table 3) and reviewed by disability professionals, violence prevention experts, and a stakeholder advisor group of people with intellectual and physical disabilities. These reviewers considered content validity and sensitivity to uncomfortable subject matter. Three reviewers independently ranked each vignette on level of complexity, so a minimum of two straightforward, moderate, and complex items was included in the final instruments (Dinora et al., 2020).

| Vignette storyline | Core concepts (Pre-Post) | Vignette complexity rating |

|---|---|---|

| Supervisor yells at an employee. | Trust, respect, boundaries | Easy |

| Assistant asks permission to help a person with counting money. | Difference between staff and friends, trust, respect, ask permission | Easy |

| Van driver sexually assaults person. | Trust, unhealthy touch, ask permission, respect | Medium |

| Friend betrays trust | Trust, respect, boundaries | Medium |

| Person is denied transportation to physical therapy as punishment. | Trust, respect | Hard |

| Staff respectfully supports a person putting away dishes. | Difference between staff and friends, respect | Hard |

A set of six video vignettes were administered to participants before the first LEAP session (pretest) and immediately after the last session (posttest) to evaluate the comprehension of concepts presented in the four intervention sessions. All vignettes were administered using an iPad, and questions associated with the vignettes were read aloud to participants. Research assistants transcribed the participant responses.

Each assessment measure followed a general structure that included dichotomous scenario identification questions (e.g., yes that is right/no that is wrong; yes, it is ok/no, it is not ok). Correct answers were coded as “1” and incorrect responses as “0,” and when summed across the six items, yielded total scores ranging from 0-6. Identification questions were followed by open-response explanation questions asking participants to describe why they made their response choice. Four of the explanation items were followed by open-ended resolution questions asking participants, “What would you do next?” The six explanation items and four resolution items were independently evaluated by three reviewers and rated as 0 “incorrect,” 1 for “partial credit,” and 2 for “full credit.” Each explanation and resolution item yielded a total of 6 possible points. Within each time point, items were summed to create a total score. “Why” explanation response totals ranged from 0-36, and resolution response totals ranged from 0-24. Independent reviewers used a predefined codebook to evaluate participant responses. Codes were developed based on the core components of the LEAP training.

LEAP Research Implementation Process

As highlighted above, this study included two data collection time points: a pretest before the first session and a posttest after the fourth final session. Personal characteristics and demographic information were collected from participating ID provider agencies. Finally, a third-party observer completed a trainer implementation fidelity checklist to monitor fidelity to the trainer implementation guidelines during each training session.

Data Analysis

Rater Agreement

At each time point, participant responses to six explanation items and four resolution items were coded by three raters. Fleiss’ Kappa was used to measure the strength of agreement among ratings submitted by the three different raters. Kappa ranges from -1 to 1, and larger scores above 0 indicate stronger agreement between raters. Generally, a Kappa score of .80 is considered a threshold for acceptable agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977).

Non-Normal Distributions

To estimate the effects of the LEAP intervention, we analyzed change between pretest and posttest for scenario identification, explanation, and resolution items. Examination of data before analysis showed that the distribution of dependent variables had skewness and kurtosis that fell within acceptable ranges. However, Q-Q plots indicated that data might have had a non-normal distribution. Kolmogorov-Smirnov and Shapiro-Wilk tests were significant (p < .05) for identification, explanation, and resolution variables at pretest and posttest, which further indicated that distributions significantly differed from distributions normal. Out of caution, nonparametric analyses were selected to show differences between pretest and posttest as well as between independent groups.

Testing Differences Between Pretest and Posttest

Wilcoxon Signed-Rank tests were used to examine differences in scores between pretest and posttest. The test was the nonparametric alternative to the paired-samples t test that ranks positive and negative score differences between time points. An approximation of the normal distribution is used to determine if systematic improvements were made during the intervention, and results were reported using the z statistic. Effect sizes were reported using r, which we interpret similarly to Cohen’s d: 0.1 represents a small effect, 0.3 medium, and 0.5 or greater as a large effect (Cohen, 1988). Rather than using means and standard deviations, we reported dispersion using the median and interquartile range. It was expected that correct responses and strength of response explanations would increase significantly at each phase of the project.

Results

Identification scores were the sum of items correctly identified as an abusive or exploitative scenario. Internal reliability for the six abuse identification items was poor at pretest (α = .15) and posttest (α = .45). The Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that pretest and posttest identification scores (z = -1.69, p > .05) were not statistically different, although scores did improve marginally, medians and results of all Wilcoxon signed-rank tests can be found in Table 4. Overall, changes in response to the intervention were limited. However, results indicated that participants initially possessed moderate awareness of abusive or exploitative situations and that their identification skills can continue to improve, if even slightly, with additional preparation.

| Median | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | N | Pre | IQR | Post | IQR |

| Identification | 95 | 4 | 4, 5 | 5 | 4, 6 |

| Explanation | 96 | 15.5 | 9, 24 | 21 | 14, 30 |

| Resolution | 107 | 12 | 5, 18 | 15 | 6,19 |

LEAP participants followed vignette identification by explaining why a situation was or was not abusive/exploitative. Unlike identification items, which were either correct or incorrect, three reviewers rated the accuracy of participant explanations. Fleiss’ Kappa was .99 and .98 at pretest and posttest, respectively, indicating strong agreement between raters at all time points.

Explanation ratings were totaled and analyzed. Test results showed that posttest scores were greater than pretests (z = -5.04, p < .001), indicating that after the LEAP participants more accurately described why situations were abusive/exploitative. The effect of these results fell in the medium-to-large range.

After explaining their rationale for identifying situations as abusive/exploitative, participants were asked to state resolutions (i.e., actions) that could be taken to address problem situations actively. Again, three raters assessed responses and determined whether no credit, partial credit, or full credit should be given for each resolution offered by participants. Strong rater agreement was found for each time point, .97 and .98, respectively. Results of the Wilcoxon test indicated that participants got better at detailing resolutions to abusive/exploitative situations after the LEAP training compared to before the training (z = -2.19, p < .01). The effect was small to medium.

Last, the average trainer implementation fidelity score was 97% across 15 sites and 12 trainers.

Discussion

As abuse awareness, prevention, and intervention programs for people with ID continue to be developed, there is a need for rigorous research that demonstrates measurable and meaningful outcomes for participants (R. B. Hughes et al., 2020; Mikton et al., 2014). This efficacy study responds to this need and addresses additional gaps in the abuse prevention literature. For example, LEAP staff intentionally recruited both men and women participants and people with more significant levels of ID participated with greater frequency than in prior studies.

The LEAP theory of change was premised on the idea that gains in knowledge would lead to changes in behavior or action. Consistent with social cognitive theory, LEAP developers hypothesized that, through the role-playing, repetition, and reinforcement that was built into the intervention, people with ID would acquire skills and perform new behaviors. These behaviors would then influence participants’ actions. The expectation was that if people with ID participated in instruction and role-playing about the differences between healthy and unhealthy relationships, how unhealthy relationships can lead to being targeted for abuse, and what to do if, in an unhealthy relationship, they would have the tools to protect themselves. As demonstrated in both the pre and posttest scores, this theory of change was confirmed in the research findings. After the intervention, people with ID improved their ability to report and contrast healthy and unhealthy relationships and better understood what to do if in an unhealthy relationship.

An important finding from the LEAP study (see Hickson et al., 2015 and R. B. Hughes et al., 2020) is that through the intervention, participants were better able to describe differences between healthy and unhealthy relationships as well as state appropriate actions to take if experiencing abuse. Immediately following the intervention, participants could use language presented in training to describe unhealthy and healthy scenarios more accurately and report what to do next if in a compromising situation. These are critical skills for addressing potential abusive situations.

There are several specific ways in which the LEAP research expanded the current ID abuse prevention literature. As recommended in best practice, rigorous implementation fidelity protocols were put into effect to ensure adherence and competence in carrying out the LEAP intervention across sites and trainers (Breitenstein et al., 2010). LEAP trainer implementation fidelity was very high. While some studies included elements of implementation fidelity as part of their research with mixed results (Hickson et al., 2015), others did not describe how they evaluated fidelity in their research design (R. B. Hughes et al., 2020). Understanding the effectiveness of any intervention is contingent on the accurate description, measurement, and implementation of the intervention (Bellg et al., 2004).

Limitations

Although efficacy results for the LEAP intervention were promising, there are several noted limitations in this research. First, although the level of ID provided some descriptive information on program participants and was used to examine differences in LEAP outcomes, the level of support need is considered central to classification, service delivery, and understanding disability (Arnold et al., 2014). In further research, we will seek to collect data on adaptive behaviors and the level of support need for participants.

When testing the intervention, we did not include a control group. A randomized study with a control group would help to improve our ability to minimize bias and use the most rigorous tools to assess cause-effect relationships between LEAP and participant outcomes (Hariton & Locascio, 2018). Additionally, measurement was a significant challenge for this study. Because many research participants did not read and did not feel comfortable with traditional paper-and-pencil “testing,” the measurement tool was adapted to a more accessible, visually based format. While we conducted extensive pilot testing, this type of measurement is relatively novel. Further testing is needed to establish the reliability of our vignette tools.

Data were non-normally distributed for all measures at all time points, which required the use of nonparametric analyses; however, parametric measures may have provided better insight into differences in the rate of change for those with different levels of ID. Our analyses used different tests to examine the same outcome variables increasing the likelihood of alpha inflation.

The identification items, which had poor internal reliability at pretest and posttest, were developed to measure a unidimensional abuse identification construct. The LEAP curriculum and video vignettes used for assessment explored diverse facets of abuse and exploitation, and poor internal reliability may indicate that items represent more than one underlying abuse and exploitation identification construct. We will continue to refine identification items and test the validity of these items and scales so that we can better discriminate differences in how people identify scenarios based on a variety of personal or contextual information.

Implications

People with ID are often targeted for abuse, neglect, and exploitation. The field must continue to research and systematically evaluate abuse prevention interventions to address this risk. The LEAP intervention was developed to provide people with ID with an understanding of the differences between healthy and unhealthy relationships and skills to protect themselves. Because outcomes from the training proved very promising, the scale-up of research-based interventions like LEAP appears to be a concrete step forward to confront these challenges to the safety of people with ID.

Progress is being made in building evidence-based strategies; however, we must also continue to refine our measurement tools and processes to meet the needs of people with ID—a heterogeneous and complex population. Finally, for training interventions, in particular, program developers should also consider incorporating measures of implementation fidelity as part of their evaluation strategy. This will improve confidence in attributing participant outcomes to the intervention. Professionals in the field must continue to work in partnership with people with disabilities, families, providers, and other stakeholders to support a culture of prevention. This will help to ensure that skills and tools presented to people with ID in training interventions can be reinforced throughout their everyday life.

References

Araten-Bergman, T., & Bigby, C. (2020). Violence prevention strategies for people with intellectual disabilities: A scoping review. Australian Social Work, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2020.1777315

Archer, A. L., & Hughes, C. (2010). Explicit instruction: Effective and efficient teaching. Guilford Press.

Arnold, S. R., Riches, V. C., & Stancliffe, R. J. (2014). I‐CAN: The classification and prediction of support needs. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 27(2), 97-111. https://doi.org/0.1111/jar.12055

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Prentice-Hall.

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Worth Publisher.

Beadle‐Brown, J., Mansell, J., Cambridge, P., Milne, A., & Whelton, B. (2010). Adult protection of people with intellectual disabilities: Incidence, nature and responses. Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 23(6), 573-584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-3148.2010.00561.x

Bellg, A. J., Borrelli, B., Resnick, B., Hecht, J., Minicucci, D. S., Ory, M., Ogedegbe, G., Orwig, D., Ernst, D., Czajkowski, S., & Treatment Fidelity Workgroup of the NIH Behavior Change Consortium. (2004). Enhancing treatment fidelity in health behavior change studies: Best practices and recommendations from the NIH behavior change consortium. Health Psychology, 23, 443-451. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-6133.23.5.443

Bowen, E., & Swift, C. (2019). The prevalence and correlates of partner violence used and experienced by adults with intellectual disabilities: A systematic review and call to action. Trauma, Violence, and Abuse, 20, 693-705. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838017728707

Breitenstein, S. M., Gross, D., Garvey, C. A., Hill, C., Fogg, L., & Resnick, B. (2010). Implementation fidelity in community‐based interventions. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(2), 164-173. https://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20373

Byrne, G. (2018). Prevalence and psychological sequelae of sexual abuse among individuals with an intellectual disability: A review of the recent literature. Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 22(3), 294-310. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629517698844

CAST. (2018). Universal design for learning guidelines version 2.2. http://udlguidelines.cast.org

Catani, C., & Sossalla I. M. (2015). Child abuse predicts adult PTSD symptoms among individuals diagnosed with intellectual disabilities. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(1600), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.01600

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, May 10). Domestic violence prevention enhancement and leadership through alliances (DELTA). http://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/delta/

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Curtiss, S. L., & Kammes, R. (2020). Understanding the risk of sexual abuse for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities from an ecological framework. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 17(1), 13-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/jppi.12318

Dinora, P., Schoeneman, A., Dellinger-Wray, M., Cramer, E. P., Brandt, J., & D’Aguilar, A. (2020). Using video vignettes in research and program evaluation for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A case study of the Leadership for Empowerment and Abuse Prevention (LEAP) project. Evaluation and Program Planning, 79, 101774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evalprogplan.2019.101774

Doughty, A., & Kane, L. (2010). Teaching abuse-protection skills to people with intellectual disabilities: A review of the literature. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 31, 331-337. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2009.12.007

Dryden, E. M., Desmarais, J., & Arsenault, L. (2017). Effectiveness of IMPACT: Ability to improve safety and self-advocacy skills in students with disabilities-follow-up study. Journal of School Health, 87(2), 83-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/josh.12474

Eastgate, G., Van Driel, M. L., Lennox, N. G., & Scheermeyer, E. (2011). Women with intellectual disabilities: A study of sexuality, sexual abuse and protection skills. Australian Family Physician, 40(4), 226–230.

Fisher, M. H., Corr, C., & Morin, L. (2016). Victimization of individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities across the lifespan. In R. M. Hodapp & D. J. Fidler (Eds.), International review of research in developmental disabilities (Vol. 51, pp. 233-280). Academic Press. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/bs.irrdd.2016.08.001

Fixsen, D. L., Naoom, S. F., Blase, K. A., Friedman, R. M., & Wallace, F. (2005). Implementation research: A synthesis of the literature. National Implementation Research Network. https://nirn.fpg.unc.edu/sites/nirn.fpg.unc.edu/files/resources/NIRN-MonographFull-01-2005.pdf

Foshee, V. A., Bauman, K. E., Ennett, S. T., Linder, G. F., Benefield, T., & Suchindran, C. (2004). Assessing the long-term effects of the Safe Dates program and a booster in preventing and reducing adolescent dating violence victimization and perpetration. American Journal of Public Health, 94(4), 619-624. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.94.4.619

Hariton, E., & Locascio, J. J. (2018). Randomised controlled trials—the gold standard for effectiveness research. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 125(13), 1716. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1111/1471-0528.15199

Harrell, E. (2012, December). Crime against persons with disabilities, 2009-2011- Statistical tables (NCJ 240299). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/capd0911st.pdf

Harrell, E. (2017, July). Crime against persons with disabilities, 2009-2015 – Statistical tables (NCJ 250632). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics. https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/capd0915st.pdf

Hickson, L., & Khemka, I. (2016). Prevention of maltreatment of adults with IDD: Current status and new directions. In J. R. Lutzker, K. Guastaferro & M. L. Benka-Coker (Eds.), Maltreatment of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (pp. 233-262). American Association on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities.

Hickson, L., Khemka, I., Golden, H., & Chatzistyli, A. (2015). Randomized controlled trial to evaluate an abuse prevention curriculum for women and men with intellectual and developmental disabilities. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 120(6), 490-503. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-120.6.490

Hughes, K., Bellis, M. A., Jones, L., Wood, S., Bates, G., Eckley, L., McCoy, E., Mikton, C., Shakespeare, T., & Officer, A. (2012). Prevalence and risk of violence against adults with disabilities: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. The Lancet, 379(9826), 1621-1629. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61851-5

Hughes, R. B., Robinson-Whelen, S., Davis, L. A., Meadours, J., Kincaid, O., Howard, L., Millin, M., Schwartz, M., McDonald, K. E., & Safety Project Consortium. (2020). Evaluation of a safety awareness group program for adults with intellectual disability. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 125(4), 304-317. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-125.4.304

Kidney, C. A., & McDonald, K. E. (2014). A toolkit for accessible and respectful engagement in research. Disability & Society, 29(7), 1013-1030. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2014.902357

Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159-174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

Lund, E. M. (2011). Community-based services and interventions for adults with disabilities who have experienced interpersonal violence: A review of the literature. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 12(4), 171-182. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838011416377

O’Malley, G., Irwin, L., & Guerin, S. (2020). Supporting people with intellectual disability who have experienced abuse: Clinical psychologists’ perspectives. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 17(1), 59-69. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1111/bld.12259

Martinez, V., Attal, N., Vanzo, B., Vicaut, E., Gautier, J. M., Bouhassira, D., & Lantéri-Minet, M. (2014). Adherence of French GPs to chronic neuropathic pain clinical guidelines: Results of a cross-sectional, randomized, “e” case-vignette survey. PLoS ONE, 9(4), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093855

Mikton, C., Maguire, H., & Shakespeare, T. (2014). A systematic review of the effectiveness of interventions to prevent and respond to violence against persons with disabilities. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(17), 3207-3226. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260514534530

National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN). (2016). The road to recovery: Supporting children with intellectual and developmental disabilities who have experienced trauma. Los Angeles, CA: Learning Center for Child and Adolescent Trauma.

Office of Justice Programs. (2018). Crimes against people with disabilities. U.S. Department of Justice, Office for Victims of Crime. https://ovc.ojp.gov/sites/g/files/xyckuh226/files/ncvrw2018/info_flyers/fact_sheets/2018NCVRW_VictimsWithDisabilities_508_QC.pdf

Oremus, M., Xie, F., & Gaebel, K. (2016). Development of clinical vignettes to describe Alzheimer’s Disease health states: A qualitative study. PLoSONE, 11(9), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0162422

Parsons, M. B., Rollyson, J. H., & Reid, D. H. (2012). Evidence-based staff training: A guide for practitioners. Behavior Analysis in Practice, 5(2), 2-11. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03391819

Rapp, W. (2014). Universal design for learning in action. Paul H. Brooks.

Smith, N., Harrell, S., & Judy, A. (2017). How safe are Americans with disabilities? The facts about violent crime and their implications. Vera Institute of Justice, Center on Victimization and Safety. https://www.endabusepwd.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/How-safe-are-americans-with-disabilities-web.pdf

Stacey, D., Brière, N., Robitaille, H., Fraser, K., Desroches, S., & Légaré, F. (2014). A systematic process for creating and appraising clinical vignettes to illustrate interprofessional shared decision making. Journal of Interprofessional Care, 28(5), 453-459. https://doi.org/10.3109/13561820.2014.911157

Stevens, B. (2012). Examining emerging strategies to prevent sexual violence: Tailoring to the needs of women with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Mental Health Research in Intellectual Disabilities, 5(2), 168-186. https://doi.org/10.1080/19315864.2011.608153

Ward, K., Windsor, R., & Atkinson, J. P. (2012). A process evaluation of the Friendships and Dating Program for adults with developmental disabilities: Measuring the fidelity of program delivery. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 33(1), 69-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2011.08.016

Ward, K., Atkinson, J., Smith, C., & Windsor, R. (2013) A friendships and dating program for adults with intellectual and developmental disabilities: A formative evaluation. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 51(1), 22-32. https://doi-org.proxy.library.vcu.edu/10.1352/1934-9556-51.01.022

Wolfe, D. A., Crooks, C., Jaffe, P., Chiodo, D., Hughes, R., Ellis, W., Stitt, L., & Donner, A. (2009). A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: A cluster randomized trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 163(8), 692-699. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.69