College Students’ Knowledge of and Openness to Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Louis W. Turchetta and Valerie Ryan

College Students’ Knowledge of and Openness to Students with Autism Spectrum Disorder PDF File

Abstract

College students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) face challenges due to limited understanding of this condition. This study investigates college students’ awareness of and openness to peers with ASD using an educational intervention. Data were analyzed via a pre–post survey design with two groups. Factorial analysis of variance showed no significant differences between groups. However, a Wilcoxon signed-rank test revealed significant differences in the treatment group’s ranks on the openness scale and knowledge scale between pre- and post-intervention surveys. Findings yielded small (openness) and large effect sizes (knowledge) as expected. Brief educational interventions in required courses can thus potentially enhance students’ knowledge and engender positive future interactions with students with ASD.

Plain Language Summary

College students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) face many social challenges. These difficulties stem from limited understanding of the disorder among students and staff. Peers’ responses may influence the academic and social success of students with ASD. This study measured college students’ awareness of and openness to students with ASD. An educational intervention was performed. No significant changes were found between groups’ scale scores and time of survey. However, the intervention group’s pre- and post-intervention scale scores differed significantly. Results show the value of educational interventions. Providing brief autism-focused education in college courses may enhance students’ knowledge. This familiarity could promote positive interactions with peers with ASD.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) affects an individual’s capacity for social cognition and communication. Students with ASD represent a growing segment of postsecondary education; an estimated 44% of high school graduates with ASD go on to attend a 2- or 4-year school (Jackson et al., 2018). Concerningly, however, students with ASD have substantially lower completion rates (i.e., between 20% and 40%) than neurotypical students 5 years after graduation (White et al., 2016). A consistent increase in the enrollment of students with ASD underscores the need to better understand these individuals (VanBergeijk et al., 2008).

The social acceptance of students with ASD at the postsecondary level is an essential aspect of their transition to adulthood (Anderson et al., 2018). A crucial barrier facing college students with ASD is a lack of understanding of this condition (Underhill et al., 2019) from both peers and instructors. Exclusion or generally unreceptive attitudes can render the college environment less hospitable to students with ASD (Gelbar et al., 2015). In particular, peer rejection can contribute to depression, aggressive behavior, and attrition among this population (Harnum et al., 2007). Families of college students with ASD frequently rank adequate support for social functioning above academic support (Camarena & Sarigiani, 2009). In fact, social support represents one of the most crucial components of college success (Gelbar et al., 2015). Many college students with ASD have cited others’ understanding of their diagnosis as a major obstacle (Nevill & White, 2011).

Theoretical Framework

Medical Model

Two popular theoretical frameworks describe disability from divergent points of view. Historically, most educational institutions have assumed a conventional medical model perspective, which stresses an individual’s functional limitations (S. R. Jones, 1996). This model frames disability as a personal experience in which rehabilitation is necessary to alleviate associated challenges. More specifically, this model depicts students with ASD as having social or developmental shortcomings that interventions are designed to address (Nevill & White, 2011). The medical model suffers from numerous deficiencies with respect to inclusion.

Social Construct Model

The second and more recent approach to defining disability describes the concept as a social construct, effectively expanding the disability framework to include all people (Denhart, 2008). This model posits that disability is socially constructed rather than purely individual. Viewing disability through this lens allows for greater appreciation of diversity in the classroom (Strange, 2000). This more inclusive framework also encourages changes to environments, thinking, and beliefs to address challenges facing people with disabilities.

The social construct model also enables institutions to craft interventions intended to improve the surrounding environment for students with ASD (Matthews et al., 2015). Interventions designed to target the environment rather than the individual may yield notable impacts; environmental improvements are especially relevant to the retention and advancement of college students with ASD (Matthews et al., 2015; Nachman & Brown, 2020; Strange, 2000).

Importance of Typical Peer Attitudes

Peers’ attitudes toward students with ASD may greatly influence these students’ academic and social outcomes. For example, the degree of social connectedness perceived by students with ASD is related to the attitudes of their neurotypical peers (Jackson et al., 2018). Peers can profoundly affect young adults’ self-concept, social skills, academic achievement, motivation, and future outcomes (Wertsch, 1985).

Students with ASD continue to struggle on college campuses, and services that promote social functioning (e.g., coaching or peer mentoring) are not required by law (Brown & Coomes, 2016). Students may also lack the social skills necessary to effectively self-advocate and often choose not to disclose details about their disability (D. R. Jones et al., 2021). Students with ASD cite social challenges as being among their greatest hurdles on college campuses; a lack of awareness among peers seems to be one of the most critical areas of need in supporting students with ASD (Anderson et al., 2018).

Typical students may misconstrue certain ASD-related behaviors, such as a lack of eye contact or misinterpretation of social cues, as reluctance to make connections. Research on perceptions of atypical behaviors in the ASD population suggests the importance of environmental change in fostering acceptance (Underhill et al., 2019). College students tend to view such behavior more negatively when it is not tied to a diagnostic label such as ASD (Brosnan & Mills, 2016; Butler & Gillis, 2011). Giving neurotypical students the means to identify and support peers with ASD may lead to greater understanding and inclusion. Additionally, raising awareness of ASD could enable neurotypical peers to better recognize associated behaviors and view them more favorably (Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2021).

Importance of Advocating for Greater Awareness

Awareness programs can potentially reduce stereotypes and stigma about students with ASD (Van Hees et al., 2015). Efforts to increase awareness of ASD may lead to improved understanding of students with the condition (Griffith et al., 2012). Raising awareness of ASD is consistent with interventions modeled after social construct theory (Matthews et al., 2015) and supported by the Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee’s (2020) strategic plan for ASD research. Furthermore, greater awareness of ASD among typical college students and faculty could improve the experience of students with ASD by reducing isolation and dropout (Griffith et al., 2012).

Promoting awareness of students with ASD in community college settings is especially important; these students are twice as likely to attend community college than a 4-year institution (Snyder et al., 2016). Students with ASD may attend community college in greater numbers for various reasons, including affordability, lower admissions requirements, accessibility, an emphasis on teaching over research, and smaller classes (Ankeny & Lehmann, 2010).

Students with ASD and their families have long advocated for campus support such as peer mentoring and ASD awareness programs. These programs may ease the transition for students with ASD (Camarena & Sarigiani, 2009). When neurotypical peers exhibit high openness and acceptance of atypical behaviors consistent with ASD, students on the spectrum can prosper (Underhill et al., 2019). Maximizing awareness and acceptance among peers and faculty could, therefore, benefit all parties. ASD awareness education can be incorporated into relevant academic courses (e.g., introductory psychology) to enhance understanding among the general student body (Nevill & White, 2011). Yet studies examining efforts to improve the environment for students with ASD are scarce (Brown & Coomes, 2016), especially at the community college level (Shmulsky & Gobbo, 2019).

Aim of Study

This study sought to assess community college students’ awareness (i.e., knowledge) of and openness to peers with ASD before and after an educational intervention. The intervention consisted of a 20-minute mini lesson on ASD created by the lead investigator and presented in his general psychology course. The mini lesson was designed to dispel common stereotypes and to promote an accurate understanding of ASD. Students’ knowledge and openness were assessed before and after the lesson and compared to a control group of students in other general psychology classes who did not receive the lesson. Related implications and directions for future research to improve educational efforts in this area are provided in closing.

Method

Participants

Participants were recruited via email and verbal announcements from four instructors (including the lead investigator) teaching general psychology at the Community College of Rhode Island (CCRI). Students received extra credit for full participation. Specifically, to be included in the data analysis, students in the experimental group were required to complete pre- and post-surveys and attend the in-class educational intervention on ASD. Control group members were required to complete only the pre- and post-survey; they did not attend the mini lesson. Sixty students were initially recruited and completed the pretest; 44 also took the posttest. The final sample (N = 44) was somewhat evenly distributed in terms of gender (56.8% women, 43.2% men). Participants were between 18 and 48 years old (M = 21.5 years). In terms of ethnicity, 58% of participants identified as White/European, 7.4% as Black, 2.5% as South Central American, 22.2% as Other Latino, 8.6% as multiracial/multiethnic, and 1.2% did not say.

Procedures

Participants completed an identical pre- and post-test including two surveys that respectively measured knowledge of ASD and openness to people with ASD. All surveys were administered through Google Forms before and after the in-class educational intervention. Participants were assigned to either the treatment or control group based on course enrollment. Those who attended the lead investigator’s class received the 20-minute mini-lesson, whereas students in other general psychology courses did not (i.e., control group).

Intervention

The lead investigator created the mini lesson and delivered it in his general psychology course. The lesson consisted of PowerPoint slides along with brief videos, including publicly available video clips depicting the perspectives of students with ASD. In terms of the lesson’s learning objectives, the intervention group was expected to be able to (a) define ASD; (b) describe aspects of the identification, intervention, and prognosis for individuals with ASD; (c) understand differences in how people with ASD may express empathy and emotion; and (d) describe how the behavior of individuals with ASD can sometimes be misunderstood.

Timeline

The experimental and control groups completed an identical posttest 1 week after the intervention. During the informed consent process, students who agreed to participate in the study were randomly assigned an ID with which the lead investigator could verify and match their pre- and posttest scores for data analysis. Personally identifying information was kept separate from participants’ responses.

Ethical Considerations

Study participation was voluntary, and all potential participants (i.e., across courses in which the study was advertised) could complete a comparable alternative assignment for extra credit if they desired. The lead investigator completed required trainings on human subjects research and received study approval from CCRI’s Institutional Review Board.

Instruments

The first survey was designed to evaluate participants’ openness to individuals with ASD. The survey included a vignette along with seven questions developed by Harnum et al. (2007). A second survey, a knowledge assessment, was administered simultaneously during the pre- and posttest; this assessment was developed by Stone (1987), adapted by Heidgerken et al. (2005), and used in a study regarding college students’ knowledge of autism (Tipton & Blacher, 2014). Both measures are provided in the Appendix.

Data Analysis

We adopted a between- and within-groups pre–post design involving two 2 × 2 factorial analyses of variance (ANOVAs). A mixed design was employed to determine whether scores on the openness scale and knowledge scale differed by group (treatment vs. control) and time of survey (pre- vs. post-intervention). We also used the Wilcoxon signed-rank test to determine whether significant differences existed in the treatment group’s ranks on the openness scale and knowledge scale between pre- and post-intervention surveys. The alpha level was 0.05. All analyses were conducted in R version 3.4.3 (R Core Team, 2017).

Results

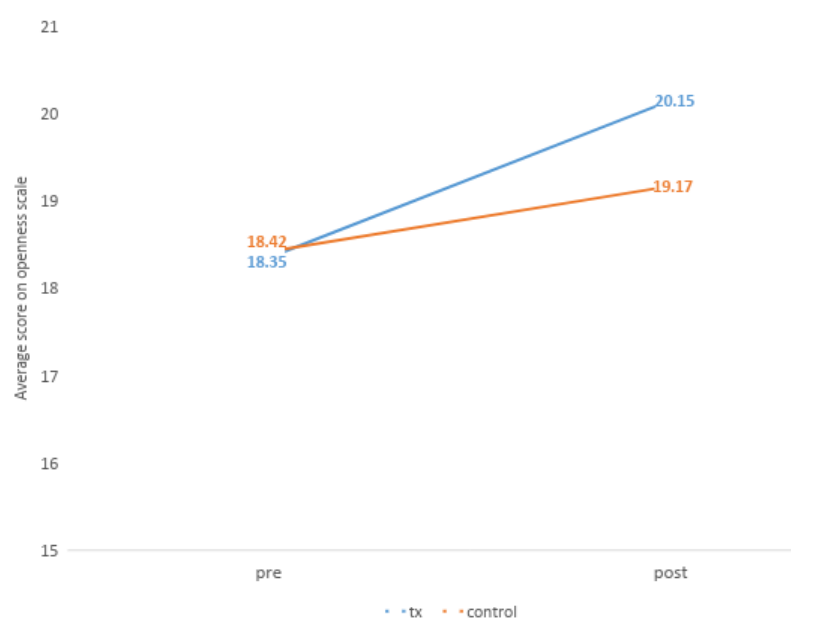

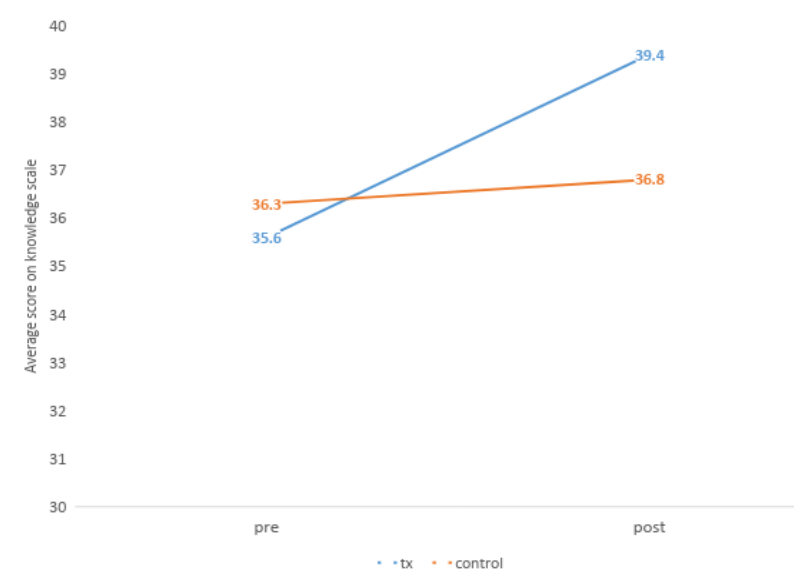

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test indicated statistically significant differences in pre- and post-test ranks on the treatment group’s openness scale (Mdnpre-test = 19 vs. Mdnpost-test 21.5; V = 27, p = 0.01) and knowledge scale (Mdnpre-test = 35 vs. Mdnpost-test = 40; V = 46.5, p = 0.03). The ranks were significantly higher for the post-tests versus the pre-tests. Students in the treatment group thus apparently held more favorable attitudes toward, and were more knowledgeable about, people with ASD following the informational mini lesson.

The Wilcoxon signed-rank test also yields an effect size, Cliff’s delta (d). This measure was small for the difference between the treatment group’s pre- and posttest scores on openness (d = 0.19) but large for the difference between their scores on knowledge (d = 0.48). The large effect size associated with knowledge indicates that this variable was substantially influenced by the intervention. The small effect size associated with openness indicates that the intervention was substantially less influential on this variable.

Discussion

The intervention showed promising results, as students’ knowledge and openness each improved in the treatment group. The lack of statistically significant interactions and main effects in the factorial ANOVAs may be due to two factors: (1) a small sample size and (2) non-normally distributed data. There were only 20 participants in the treatment group and 24 in the control group, resulting in little power to detect significant effects. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test, a non-parametric test analogous to a dependent samples t test, was, therefore, a better candidate for analyzing these data.

The statistically significant results of the Wilcoxon signed-rank test suggest an expected large effect size for change in knowledge and an expected small effect size for change in openness. Tests of factual knowledge often show large gains after an educational intervention (Gillespie-Lynch et al., 2021). Scholars have also found that implicit attitudes, such as openness, may be more resistant to awareness training (D. R. Jones et al., 2021). Research on implicit attitude change highlights the quantity or amount of contact as the most critical element for change (Gardiner & Iarocci, 2014). Knowledge or explicit awareness of the need for change is typically the first stage in a change process. The transtheoretical model of change asserts that when attempting to change behavior, attitude change through consciousness raising or promotion of awareness is usually the first step (Prochaska & Norcross, 2001). Our findings imply that awareness initiatives, such as a mini lesson in a general psychology class, can substantially improve knowledge and marginally improve openness in typical students. These results are consistent with those of Van Hees et al. (2015), who reported large increases in knowledge and modest increases in openness after an educational intervention.

Furthermore, consistent with Gillespie-Lynch et al. (2021), openness did not change substantially; however, educational interventions may initially help students to understand individuals with ASD. An educational intervention and initial improvement in explicit knowledge could serve as a prerequisite for positive future interactions. More specifically, before considerable gains in openness can be realized, typical students may first need knowledge in addition to multiple opportunities to be in the presence of students with ASD over extended periods and with repeated exposure.

Limitations

The limitations of this research include its small sample size and uncertainty regarding the retention of participants’ gains in knowledge and openness after post-measures were collected. Additionally, students who chose to participate in this study for extra credit may have fundamentally differed from those who opted not to take part.

In the future, researchers could recruit a larger sample size and adopt a follow-up design to determine whether any increases in participants’ scores have lasting effects. Scholars can also examine the impacts of intervention programs on student populations who have already received ASD education.

Conclusion

Ideally, subsequent research and interventions combining education and other best practice measures (e.g., peer mentoring) could increase students’ extent of positive exposure to and experiences with ASD, possibly enhancing openness over time. Students with ASD may particularly benefit from policies that incorporate awareness education into introductory coursework for all students.

References

Anderson, K. A., Sosnowy, C., Kuo, A. A., & Shattuck, P. T. (2018). Transition of individuals with autism to adulthood: A review of qualitative studies. Pediatrics, 141(Suppl 4), S318–S327. https://doi.org/ 10.1542/peds.2016-4300I

Ankeny, E. M., & Lehmann, J. P. (2010). The transition lynchpin: The voices of individuals with disabilities who attended a community college transition program. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 34(6), 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668920701382773

Brosnan, M., & Mills, E. (2016). The effect of diagnostic labels on the affective responses of college students toward peers with ‘Asperger’s Syndrome’ and ‘Autism Spectrum Disorder.’ Autism, 20(4), 388–394. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362361315586721

Brown, K. R., & Coomes, M. D. (2016). A spectrum of support: Current and best practices for students with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) at community colleges. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 40(6), 465–479. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2015.1067171

Butler, R. C., & Gillis, J. M. (2011). The impact of labels and behaviors on the stigmatization of adults with Asperger’s disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(6), 741–749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-010-1093-9

Camarena, P. M., & Sarigiani, P. A. (2009). Postsecondary educational aspirations of high-functioning adolescents with autism spectrum disorders and their parents. Focus on Autism and Other Developmental Disabilities, 24(2), 115–128. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1088357609332675

Denhart, H. (2008). Deconstructing barriers: Perceptions of students labeled with learning disabilities in higher education. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(6), 483–497. https://doi.org/10.1177% 2F0022219408321151

Gardiner, E., & Iarocci, G. (2014). Students with autism spectrum disorder in the university context: Peer acceptance predicts intention to volunteer. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(5), 1008–1017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-013-1950-4

Gelbar, N. W., Smith, I., & Reichow, B. (2015). Systematic review of articles describing experience and supports of individuals with autism enrolled in college and university programs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(10), 2593–2601. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2135-5

Gillespie-Lynch, K., Daou, N., Obeid, R., Reardon, S., Khan, S., & Goldknopf, E. J. (2021). What contributes to stigma towards autistic university students and students with other diagnoses? Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(2), 459–475. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04556-7

Griffith, G. M., Totsika, V., Nash, S., & Hastings, R. P. (2012). ‘I just don’t fit anywhere’: Support experiences and future support needs of individuals with Asperger syndrome in middle adulthood. Autism, 16(5), 532–546. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362361311405223

Harnum, M., Duffy, J., & Ferguson, D. A. (2007). Adults’ versus children’s perceptions of a child with autism or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37(7), 1337–1343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-006-0273-0

Heidgerken, A. D., Geffken, G., Modi, A., & Frakey, L. (2005). A survey of autism knowledge in a health care setting. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 35(3), 323–330. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10803-005-3298-x

Interagency Autism Coordinating Committee. (2020, July). IACC strategic plan for autism spectrum disorder (ASD) 2018-2019 update. https://iacc.hhs.gov/publications/strategic-plan/2019/

Jackson, S. L. J., Hart, L., Brown, J. T., & Volkmar, F. R. (2018). Brief report: Self-reported academic, social, and mental health experiences of postsecondary students with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(3), 643–650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3315-x

Jones, S. R. (1996). Toward inclusive theory: Disability as social construction. NASPA Journal, 33(4), 347–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.1996.11072421

Jones, D. R., DeBrabander, K. M., & Sasson, N. J. (2021). Effects of autism acceptance training on explicit and implicit biases toward autism. Autism, 25(5), 1246–1261. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1362361320984896

Matthews, N. L., Ly, A. R., & Goldberg, W. A. (2015). College students’ perceptions of peers with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(1), 90–99. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10803-014-2195-6

Nachman, B. R., & Brown, K. R. (2020). Omission and othering: Constructing autism on community college websites. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 44(3), 211–223. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/10668926.2019.1565845

Nevill, R. E., & White, S. W. (2011). College students’ openness toward autism spectrum disorders: Improving peer acceptance. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 41(12), 1619–1628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-011-1189-x

Prochaska, J. O., & Norcross, J. C. (2001). Stages of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(4), 443–448. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.443

R Core Team. (2017). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Shmulsky, S., & Gobbo, K. (2019). Autism support in a community college setting: Ideas from intersectionality. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 43(9), 648–652. https://doi.org/10.1080/10668926.2018.1522278

Snyder, T. D., de Brey, C., & Dillow, S. A. (2016). Digest of education statistics 2014 (50th ed.). National Center for Educational Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubs2016/2016006.pdf

Stone, W. L. (1987). Cross-disciplinary perspectives on autism. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 12(4), 615–630. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/12.4.615

Strange, C. (2000). Creating environments of ability. In H. A. Belch (Ed.), New directions for student services: Serving students with disabilities (pp. 19–30). Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Tipton, L. A., & Blacher, J. (2014). Brief report: Autism awareness: Views from a campus community. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 44(2), 477–483. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10803-013-1893-9

Underhill, J. C., Ledford, V., & Adams, H. (2019). Autism stigma in communication classrooms: Exploring peer attitudes and motivations toward interacting with atypical students. Communication Education, 68(2), 175–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634523.2019.1569247

Van Hees, V., Moyson, T., & Roeyers, H. (2015). Higher education experiences of students with autism spectrum disorder: Challenges, benefits and support needs. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 45(6), 1673–1688. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-014-2324-2

VanBergeijk, E., Klin, A., & Volkmar, F. (2008). Supporting more able students on the autism spectrum: College and beyond. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(7), 1359. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10803-007-0524-8

Wertsch, J. V. (1985). Vygotsky and the social formation of mind. Harvard University Press.

White, S. W., Elias, R., Salinas, C. E., Capriola, N., Conner, C. M., Asselin, S. B., Miyazaki, Y., Mazefsky, C. A., Howlin, P., & Getzel, E. E. (2016). Students with autism spectrum disorder in college: Results from a preliminary mixed methods needs analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 56, 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2016.05.010