Parents’ Beliefs Regarding Shared Reading with Infants and Toddlers

Emma Brezel MBE; Libby Hallas-Muchow MS; Alefyah Shipchandler; Jennifer Hall-Lande PhD, LP; and Karen Bonuck PhD

Parents’ Beliefs Regarding Shared Reading with Infants and Toddlers PDF File

Abstract

Parent beliefs about reading to young children—and factors related to such beliefs—affect a child’s reading skill. But little is known about parent beliefs about reading to infants and toddlers. To fill this gap, three University Centers for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDDs) studied 43 English- and Spanish-speaking parents of children 9-18 months of age. The three UCEDDs were working on a project to create a children’s book that had tips for parents about how their 1-year-old learns and grows. The UCEDD study survey asked about parent beliefs regarding reading to young children (4 questions) and factors related to those beliefs (2 questions). Parents were also asked to give feedback about the book. Nearly all parents agreed that children should be read to as infants and that this helps children develop reading skills. Most (62%) parents said it was “very common” for friends and family to read with children of this age. Parents said that reading the board-book together was useful for “promot[ing] language,” “help[ing] my baby’s development,” and “help[ing] my child speak.” More research like this can identify ways to help parents of young children develop reading skills.

Plain Language Summary

Reading books with young children helps them learn to read. What parents think about how children learn to read affects what they do to help children learn to read. There is not much information about this topic in parents of infants and toddlers. This paper reports on a study by three UCEDDs helping to create a children’s board-book. The UCEDD study surveyed 43 parents of 9- to 18-month-old children. The UCEDD study also tape-recorded what parents said about reading the board-book with their children. Most parents agree that reading to infants is the right thing to do and that it helps them become better readers. Parents thought the board-book would help their child’s language and speech.

Introduction

A child’s home literacy environment (HLE) predicts later literacy (Farver et al., 2013; Lancy, 1994; Sulzby & Teale, 1991). The HLE encompasses activities, resources, and attitudes (Bracken & Fischel, 2008; Burgess et al., 2002; Frijters et al., 2000; Weigel et al., 2006a), They include print-focused (e.g., providing names and sounds for letters), book-directed, non-print focused (e.g., shared book reading), and joint attention activities (e.g., caregiver-child conversations; Bracken & Fischel, 2008; Schmitt et al., 2011). HLE measures are predictive of children’s later literacy outcomes, even adjusting for demographics (Gottfried et al., 2015; Tamis-LeMonda et al., 2019; Van Steensel, 2006; Weigel et al., 2006b).

Shared book reading is the most commonly studied HLE activity (Roberts et al., 2005)—its timing, quantity, and quality impact school readiness (Cates et al., 2017; Raikes et al., 2006). Furthermore, parents/caregiver (hereafter parents) HLE beliefs affect subsequent HLE behavior (DeBaryshe, 1995; Landry & Smith, 2007). Parents’ literacy beliefs are influenced by factors including culture, socioeconomic status (SES), parents’ own reading ability, interest, and experiences. Some cultures encourage conversation with children during infancy, others not until they are perceived to be old enough to understand and respond (Hoff, 2006). In one study, just one third of U.S. immigrant Latino families reported that children under 5 years old could understand an explanation of text; 5 years of age was identified as “la edad de la razon” (age of reason; Reese & Gallimore, 2000).

Poverty can compromise school readiness—65% of all fourth graders in the U.S. are not proficient readers vs 79% of those who are low-income (National Center for Education Statistics [NAEP], 2019). Children from lower income backgrounds are read to less, hear fewer total words and less different words, and have fewer literacy resources (Huttenlocher et al., 2007) Still, parental beliefs about literacy development can mediate the effects of these demographics upon literacy outcomes (Rowe et al., 2016; Zajicek-Farber, 2010). However, research on parents’ literacy beliefs has focused on White, higher SES parents of children aged preschool or older (Hammer et al., 2005; Hart & Risley, 1995; Perry et al., 2008; Reese & Gallimore, 2000). Several dissertations have examined the literacy beliefs among parents of color for very young (i.e., below preschool-age) children (Donohue, 2009; Edwards, 2008). A more recent qualitative study found that low-income African-American and Puerto-Rican parents were highly attuned to the importance of the HLE for their preschoolers, but had less explicit understanding of specific strategies to use (Sawyer et al., 2018).

To address the gap in research on literacy beliefs among parents of infants and toddlers, we conducted a study of parents of 9- to 18-month-old children. We incorporated this Parent Beliefs about Early Reading (“PBER”) study into a larger U.S. Learn the Signs, Act Early (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 2020) related project funded by the Association of University Centers on Disabilities (AUCD) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (hereafter referred to as the CDC project). The goal of this project was to develop a board book for 1-year-olds and their parents to complement existing books for 2- and 3-year-olds children This book—Baby’s Busy Day: Being One is So Much Fun!—was designed with content on developmental milestones and parenting tips to promote and monitor development to complement existing books for 2- and 3-year-old children and their parents (CDC, 2020; Harrell, 2019). The goal of this PBER study was to provide exploratory data on parents’ (a) beliefs about reading with young children and (b) factors that might influence those beliefs (see the Appendix for the PBER survey items).

Methods

Settings

The CDC partnered with AUCD to select the following three UCEDDs from which the PBER study sample was recruited:

- University of Minnesota UCEDD—recruited from two childcare providers, the Minnesota State Fair, an Early Head Start, and local community events. At the Minnesota State Fair, the Early Head Start, and the community events, families of young children were approached by study staff.

- University of Indiana UCEDD—recruited from libraries throughout Indiana as well as childcare providers and local agencies serving Spanish-speaking individuals.

- Rose F. Kennedy UCEDD (Bronx NY) —recruited from: (a) an Early Head Start program serving predominately Spanish-speaking parents and their 1- to 4-year-old children; (b) the Infant-Parent Court Project, which provides trauma-informed care for parents and their children aged birth to 3 years; and (c) Einstein/Montefiore employees.

This study was approved by the institutional review boards of all sites. Participants completed consent forms in English or Spanish, depending upon their preference.

Eligibility

Study participants were drawn from the CDC project (n = 67), for which parent eligibility criteria were (a) age > 18 years, (b) spoke and read in English or Spanish, (c) was the primary caregiver for a 9- to 18-month-old child, (d) did not work with children with developmental delays, and (e) did not have a child who was evaluated for developmental delays. CDC project participants who completed PBER items prior to dyadic observations (see Figure 1) were included in this study.

Data

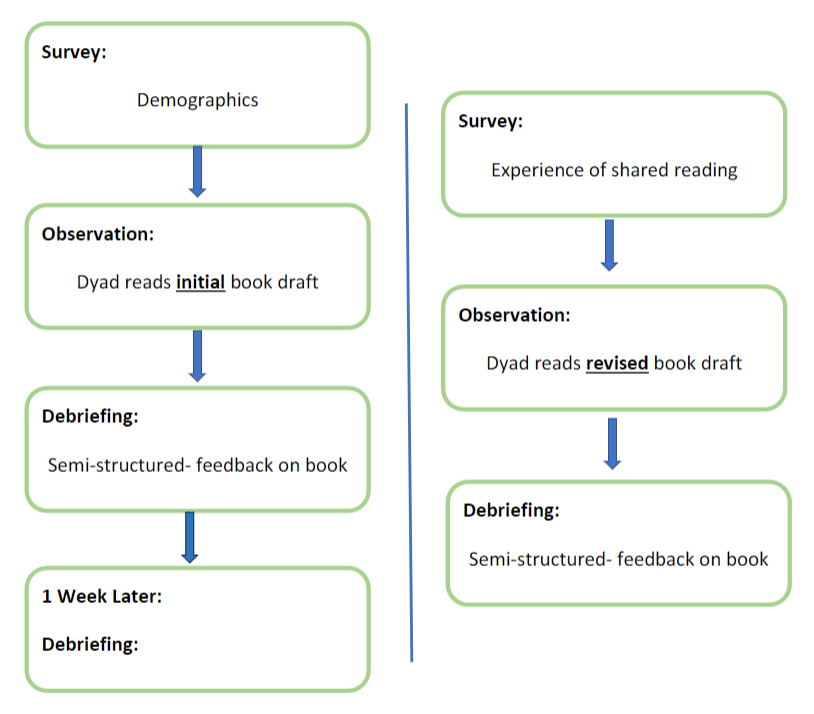

The larger CDC project collected and analyzed parent data regarding initial and revised versions of Baby’s Busy Day in English and Spanish. These data included: (a) Survey—with questions on demographics, Baby’s Busy Day, and PBER (6 items); (b) Observational—site staff structured ratings completed during dyadic (parent-child) reading of Baby’s Busy Day, and (c) Debrief—semistructured interview(s) and/or focus group(s) immediately after dyadic observations. See Figure 1 for study flow. The PBER items regarding parent’s beliefs about reading to young children (4 items) and factors that may influence those beliefs (2 items) were developed by New York staff. Spanish-speaking participants were interviewed by Spanish-speaking study staff.

Demographic and PBER survey data are presented as n and %, as appropriate. Debriefings at the New York site were audiotaped and transcribed (Indiana and Minnesota were unable to audiotape debriefings). New York staff reviewed the transcriptions for quotes that were most illustrative of the PBER items. These qualitative debriefing data are presented alongside the relevant PBER survey data in the Results section. Note, bracketed text was added to improve the clarity of quotes.

Results

Participant Demographics

As shown in Table 1, most of the participants (n = 43) were female (93%) and > 30 years (72%). Just over half identified as Hispanic/Latino (51%), had a college degree (54%), and an annual income > $30,000 (56%). A higher proportion of Indiana and Minnesota participants spoke English as a primary language, did not identify as White or Hispanic/Latinos were > 30 years, and had incomes > $30,000, compared to New York participants.

| Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participant demographics | Indiana (n = 5) | Minnesota (n = 17) | New York (n = 21) | (n = 43) | % |

| Parent age | |||||

| < 30 years | 2 | 0 | 10 | 12 | 28 |

| >30 years | 3 | 17 | 11 | 31 | 72 |

| Parent gender | |||||

| Female | 5 | 14 | 21 | 40 | 93 |

| Male | 0 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 7 |

| Race | |||||

| Asian | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Black/African American | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| White | 5 | 14 | 3 | 22 | 51 |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 12 | 12 | 28 |

| Prefer not to answer | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 7 |

| Hispanic or Latino origin | |||||

| Yes | 1 | 2 | 19 | 22 | 51 |

| No | 4 | 15 | 2 | 21 | 49 |

| Education | |||||

| Less than college degree | 2 | 2 | 13 | 20 | 47 |

| College degree or higher | 3 | 15 | 8 | 23 | 54 |

| Annual household income | |||||

| Below $30,000 | 1 | 0 | 9 | 12 | 28 |

| Above $30,000 | 4 | 17 | 5 | 24 | 56 |

| Prefer not to answer | 0 | 0 | 7 | 7 | 16 |

| Main language spoken at home | |||||

| English | 4 | 15 | 8 | 27 | 63 |

| Spanish | 1 | 2 | 13 | 16 | 37 |

Parent Beliefs (4 items)

As shown in Table 2, nearly all parents (93%) affirmed that parents should start reading with children during infancy (birth-12 months). Debriefing data found that many parents reported reading with their 9- to 18-month-old children a few times per week or “everyday” and that reading was “a standard part of [their] bedtime routine.” Several affirmed the value of reading age-appropriate books with children of this age. One stated that Baby’s Busy Day was “at the same level of stories I usually read with [my child]” and another responded that the book was “a good gift for a 1st birthday.”

| Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey items | Indiana | Minnesota | New York | n | % |

| At what age should parents start reading to their children? | |||||

| Infancy (birth-12 months) | 5 | 17 | 18 | 40 | 93 |

| Younger toddler (12-24 months) | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| Older toddler (24-36 months) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Preschooler or older (3 years or older) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Some parents think reading to children at this age helps them learn how to read when they are older. Do you agree? | |||||

| Agree | 5 | 15 | 17 | 37 | 90 |

| Neither agree nor disagree | 0 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 7 |

| Disagree | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| How necessary is it to read books with a child at this age (about 9-18 months)? | |||||

| Very | 5 | 14 | 18 | 37 | 88 |

| Somewhat | 0 | 3 | 2 | 5 | 12 |

| Not very | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Do you have time to read to your child as much as you would like to? | |||||

| Yes | 4 | 8 | 8 | 20 | 48 |

| Sometimes | 1 | 6 | 12 | 19 | 45 |

| No | 0 | 3 | 0 | ||

Similarly, 90% of parents believed that shared reading with children of this age helps them learn to read when they are older. Qualitative comments reflect parents’ awareness of the value of pre-literacy skills. Parents stated that reading Baby’s Busy Day with their children was useful for “promot[ing] language,” “help[ing] my baby’s development,” and “help[ing] my child speak.” Parents described the book’s size and materials as encouraging their child’s involvement in reading: (a) “[I] like that it’s a board book and that it’s a size that a child can hold on to. He was more interested in picking up the book and playing with pages;” and (b) “They like books where they can touch things…textures, noises, things that can interact with.” Parents appreciated the “Parent Tips”—brief suggestions to involve children during reading in order to promote development, provided in each page spread. One parent said “…when you have a baby, they don’t give you a manual…and when you’re reading books they don’t say ‘point to something so baby understands’…so I thought it was pretty awesome that it has those points [Parent Tips].”

Nearly all (90%) parents affirmed the necessity of shared reading with 9- to 18-month-old children. Parents noted that they had “books like this [Baby’s Busy Day]” or the “same level of stories” (Spanish) at home. Varied reasons were offered to support their stance (e.g., reading teaches children different skills and promotes quality time between parent and child). Several parents referred to Baby’s Busy Day as a “tool for child development” because by mimicking characters in the story, children could learn skills like “recogniz[ing] body parts” and “get[ting] herself dressed.” Additionally, one parent commented, “My favorite was page 7 where the baby hugged the sister…. I would like to see my two daughters hug like that.” Two parents emphasized reading together was a way for parent and child to bond. They enjoyed that Baby’s Busy Day encouraged children “to participate with me” and “made reading time more interesting for us to spend quality time together.” Just under half (48%) of parents reported having enough time to read their children.

Factors That Might Influence Beliefs (2 items)

When asked about reading practices of their friends and family, 62% responded that reading with 9- to 18-month-old children was very common and approximately 36% of participants responded somewhat common (Table 3). Over 90% of parents reported that they personally enjoy reading.

| Total | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Survey items | Indiana | Minnesota | New York | n | % |

| How common is it for your friends and family to read books with a child at this age (about 9-18 months)? | |||||

| Very | 3 | 12 | 11 | 26 | 62 |

| Somewhat | 2 | 5 | 8 | 15 | 36 |

| Not very | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Do you enjoy reading (e.g., magazines, books, online articles)? | |||||

| Yes | 5 | 17 | 17 | 39 | 93 |

| Sometimes | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 7 |

| No | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Discussion

Shared reading from infancy promotes emergent literacy skills. Yet less than half of 0- to 5-year-old children are read to daily (Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health, U.S. 2018). even fewer from low-income families (National Center for Education Statistics, n.d.)– falling short of the Healthy People 2020 target (Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, 2020). Thus, we conducted a study of literacy beliefs among parents of young children in three states from diverse backgrounds. Nearly all parents endorsed reading to a child before their first birthday, and that reading to children aged 9-18 months helped them learn to read. Yet, just under half of parents feel like they have enough time to read.

Overall, respondents’ beliefs align with the emergent literacy paradigm, which values reading aloud to children starting from birth. Our study did not ask about reading behaviors, but we note that parents who supported this paradigm were more likely to practice behaviors consistent with it (e.g., providing reading materials and demonstrating reading and writing; Bingham, 2007; Lynch et al., 2006). Given that experiences and environment influence their literacy beliefs and behaviors, it is notable that nearly all respondents affirmed the value of reading with very young children. Finally, nearly all respondents enjoyed reading. Parental enjoyment of reading and their self-efficacy as a teacher was related to their literacy beliefs and their child’s motivation to read (Baker & Scher, 2002; Bingham, 2007). Therefore, respondents’ enjoyment of reading may be associated with their beliefs about early onset of parent-child reading and the importance of reading with infants to their emergent literacy skills.

The study has strengths and limitations. A key strength is exploration of this topic in an under-studied population (i.e., parents of very young children). Additional strengths include a sample that was drawn from three states and that was racially, ethnically, and socioeconomically diverse—including 51% Hispanic/Latino. Further, the qualitative data provides useful context for the survey responses. Key limitations include a small, nonrepresentative convenience sample. In addition, embedding our PBER study within the larger CDC project limited the ability to obtain more detailed and nuanced data. For example, survey items focused on shared book reading, rather than other literacy-promoting activities, given the CDC project focus on developing Baby’s Busy Day. Additionally, as the CDC project sought feedback on a book about developmental milestones, this may have influenced respondents’ perceptions of shared reading and development.

Nevertheless, our findings serve as an important starting point for more research on literacy beliefs of parents of infants and from diverse backgrounds and geographic locations. Parental literacy beliefs are a critical component of the HLE and can mediate the effects of parent characteristics such as education on literacy outcomes (Cottone, 2012; DeBaryshe, 1995). Therefore, future research should focus on how parental beliefs about reading with young children influence parental literacy behaviors and children’s literacy outcomes.

References

Baker, L., & Scher, D. (2002). Beginning readers’ motivation for reading in relation to parental beliefs and home reading experiences. Reading Psychology, 23(4), 239-269. https://doi.org/10.1080/713775283

Bingham, G. E. (2007). Maternal literacy beliefs and the quality of mother-child book-reading interactions: Associations with children’s early literacy development. Early Education and Development, 18(1), 23-49. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280701274428

Bracken, S. S., & Fischel, J. E. (2008). Family reading behavior and early literacy skills in preschool children from low-income backgrounds. Early Education and Development, 19(1), 45-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409280701838835

Burgess, S. R., Hecht, S. A., & Lonigan, C. J. (2002). Relations of the home literacy environment (HLE) to the development of reading-related abilities: A one-year longitudinal study. Reading Research Quarterly, 37(4), 408-426. https://doi.org/10.1598/rrq.37.4.4

Cates, C., Weisleder, A., Dreyer, B., Johnson, M., Seery, A., Canfield, C. F., Berkule Johnson, S., & Mendelsohn, A. L. (2017). Early reading matters: Long-term impacts of shared bookreading with infants and toddlers on language and literacy outcomes. American Academy of Pediatrics. https://www.readingrockets.org/research-by-topic/early-reading-matters-long-term-impacts-shared-bookreading-infants-and-toddlers

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Learn the signs. Act Early. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/index.html

Cottone, E. A. (2012). Preschoolers’ emergent literacy skills: The mediating role of maternal reading beliefs. Early Education and Development, 23(3), 351-372. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2010.527581

Data Resource Center for Child and Adolescent Health supported by the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2018). Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Initiative. 2017-2018 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH). https://www.childhealthdata.org/

DeBaryshe, B. D. (1995). Maternal belief systems: Linchpin in the home reading process. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 16(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1016/0193-3973(95)90013-6

Donohue, K. (2009). Children’s early reading: How parents’ beliefs about literacy learning and their own school experiences relate to the literacy support they provide for their children. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences, 69 (10-A).

Edwards, C. M. (2008). The relationship between parental literacy and language practices and beliefs and toddler’s emergent literacy skills. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, Vol 68(10-B), 6628-6628.

Farver, J. A. M., Xu, Y., Lonigan, C. J., & Eppe, S. (2013). The home literacy environment and Latino head start children’s emergent literacy skills. Developmental Psychology, 49(4), 775-791.

Fernald, A., Marchman, V. A., & Weisleder, A. (2013). SES differences in language processing skill and vocabulary are evident at 18 months. Developmental Science, 16(2), 234-248. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12019

Frijters, J. C., Barron, R. W., & Brunello, M. (2000). Direct and mediated influences of home literacy and literacy interest on prereaders’ oral vocabulary and early written language skill. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(3), 466-477. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.3.466

Gottfried, A. W., Schlackman, J., Gottfried, A. E., & Boutin-Martinez, A. S. (2015). Parental provision of early literacy environment as related to reading and educational outcomes across the academic lifespan. Parenting, 15(1), 24-38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2015.992736

Hammer, C. S., Nimmo, D., Cohen, R., Draheim, H. C., & Johnson, A. A. (2005). Book reading interactions between African American and Puerto Rican Head Start children and their mothers. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 5(3), 195-227.

Harrell, A. (2019). Baby’s busy day: Being one is so much fun! Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/actearly/pdf/books/Babys-Busy-Day_English_Cover-Pages_508.pdf

Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

Hoff, E. (2006). How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental Review, 26(1), 55-88. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2005.11.002

Huttenlocher, J., Vasilyeva, M., Waterfall, H. R., Vevea, J. L., & Hedges, L. V. (2007). The varieties of speech to young children. Developmental Psychology, 43(5), 1062-1083. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.5.1062

Lancy, D. (1994). The conditions that support emergent literacy. In D. Lancy (Ed.), Children’s emergent literacy: From research to practice (pp. 1-20). Praeger Publishers.

Landry, S. H., & Smith, K. E. (2007). The influence of parenting on emerging literacy skills. Handbook of Early literacy research, 2, 135-148.

Lynch, J., Anderson, J., Anderson, A., & Shapiro, J. (2006). Parents’ beliefs about young children’s literacy development and parents’ literacy behaviors. Reading Psychology, 27(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/02702710500468708

National Center for Education Statistics. (2019). NAEP report card: Reading The Nation’s Report Card. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov/reading/nation/achievement/?grade=4

National Center for Education Statistics. (n.d.) Family reading to young children: Percentage of children ages 3–5 who were read to three or more times in the last week by a family member by child and family characteristics, selected years 1993–2016. US Department of Education. https://www.childstats.gov/americaschildren19/tables/ed1.asp#a

Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. (2020). Healthy People 2020, EMC 2.3: Increase the proportion of parents who read to their young child. Washington DC: Author. https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/objective/emc-23

Perry, N. J., Kay, S. M., & Brown, A. (2008). Continuity and change in home literacy practices of Hispanic families with preschool children. Early Child Development and Care, 178(1), 99-113.

Raikes, H., Pan, B. A., Luze, G., Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Brooks-Gunn, J., Constantine, J., Tarullo, L. B., Raikes, H. A., & Rodriguez, E. T. (2006). Mother-child bookreading in low-income families: Correlates and outcomes during the first three years of life. Child Development, 77(4), 924-953.

Reese, L., & Gallimore, R. (2000). Immigrant Latinos’ cultural model of literacy development: An evolving perspective on home-school discontinuities. American Journal of Education, 108(2), 103-134. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1085760

Roberts, J., Jergens, J., & Burchinal, M. (2005). The role of home literacy practices in preschool children’s language and emergent literacy skills. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48(2), 345-359. https://doi.org/doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2005/024)

Rowe, M. L., Denmark, N., Harden, B. J., & Stapleton, L. M. (2016). The role of parent education and parenting knowledge in children’s language and literacy skills among White, Black, and Latino families. Infant and Child Development, 25(2), 198-220. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.1924

Sawyer, B. E., Cycyk, L. M., Sandilos, L. E., & Hammer, C. S. (2018). ‘So many books they don’t even all fit on the bookshelf’: An examination of low-income mothers’ home literacy practices, beliefs and influencing factors. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 18(3), 338-372. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798416667542

Schmitt, S. A., Simpson, A. M., & Friend, M. (2011). A longitudinal assessment of the home literacy environment and early language. Infant and child development, 20(6), 409-431. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.733

Sulzby, E., & Teale, W. H. (1991). Emergent literacy. In P. D. Pearson, R. Barr, M. L. Kamil, & P. Mosenthal (Eds.), Handbook of reading research (pp. 727-757). Longman.

Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Luo, R., McFadden, K. E., Bandel, E. T., & Vallotton, C. (2019). Early home learning environment predicts children’s 5th grade academic skills. Applied Developmental Science, 23(2), 153-169. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2017.1345634

Van Steensel, R. (2006). Relations between socio-cultural factors, the home literacy environment and children’s literacy development in the first years of primary education. Journal of Research in Reading, 29(4), 367-382. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9817.2006.00301.x

Weigel, D. J., Martin, S. S., & Bennett, K. K. (2006a). Contributions of the home literacy environment to preschool‐aged children’s emerging literacy and language skills. Early Child Development and Care, 176(3-4), 357-378. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430500063747

Weigel, D. J., Martin, S. S., & Bennett, K. K. (2006b). Mothers’ literacy beliefs: Connections with the home literacy environment and pre-school children’s literacy development. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy, 6(2), 191-211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468798406066444

Zajicek-Farber, M. L. (2010). The contributions of parenting and postnatal depression on emergent language of children in low-income families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 19(3), 257-269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-009-9293-7

Zill, N., & West, J. (2001). Findings from the Condition of Education 2000: Entering kindergarten children (NCES 2001-035). Washington, DC: National Center for Education Statistics. https://nces.ed.gov/pubsearch/pubsinfo.asp?pubid=2001035