15 Person-Centered Practice as Anchor and Beacon: Pandemic Wisdom from the NCAPPS Community

Connor Bailey; Martha Barbone; Lydia X.Z. Brown; Alixe Bonardi; Bevin Croft; Marian Frattarola-Saulino; Karyn Harvey; Miso Kwak; Kelly Lang; Nicole LeBlanc; Michelle C. Reynolds; and Carole Starr

Bailey, C., Barbone, M., Brown, L., Bonardi, A., Croft, B., Frattarola-Saulino, M., Harvey, K., Kwak, M., Lang, K., LeBlanc, N., Reynolds, M., & Starr, C. (2021). Person-Centered Practice as Anchor and Beacon: Pandemic Wisdom from the NCAPPS Community. Developmental Disabilities Network Journal, 1(2), 192–209. https://doi.org/10.26077/9b0f-cc3f

Person-Centered Practice as Anchor and Beacon: Pandemic Wisdom from the NCAPPS Community PDF File

Plain Language Summary

COVID-19 is a new virus that has changed all of our lives. It has been especially challenging for people with disabilities. The National Center on Advancing Person-Centered Practices and Systems or NCAPPS is a group of people who help everyone to live their lives the way they want to. To be person-centered means that nothing is done to or for a person without their permission.

The National Center on Advancing Person-Centered Practices and Systems (NCAPPS) asked their community members to share how important it is for all of us to be person-centered during this time of COVID-19. Sixteen people shared their thoughts and experiences by recording their own short video. The 16 people were all different. Some were people using services, some were people who provide services, and some were researchers. Each person made a short video that is now on the NCAPPS website, YouTube channel and Facebook page. You can find these videos when you search for “NCAPPS Pandemic Wisdom.”

NCAPPS wanted to share what they have learned from those sixteen videos with everyone. NCAPPS worked with some of the people who shared their thoughts in the video to summarize and organize main ideas. Here are the big four themes.

- The challenges we face because of COVID-19.

- How we can use person-centered practices to get through these hard times.

- How we can help each other make good decisions and take care of each other.

- What we can do as a community to work together to get through COVID-19 and make positive changes.

NCAPPS believes that being person-centered is more important now than in any other time. NCAPPS hopes that people with disabilities and those who support them will continue working together through COVID-19. Working together to make sure we all are being person-centered will guide us to get through this difficult time safely.

Introduction

Historically, pandemics have forced humans to break with the past and imagine their world anew. This one is no different. It is a portal, a gateway between one world and the next. We can choose to walk through it, dragging…our prejudice…behind us. Or we can walk through lightly, with little luggage, ready to imagine another world. And ready to fight for it.

~Excerpt from “The Pandemic Is a Portal,” an essay by Arundhati Roy (2000)

As Roy suggests in the above-quoted passage, the COVID-19 pandemic represents a transformational moment for all aspects of society, and disability support systems are no exception. As disability advocates and leaders in the disability services sector find themselves at “a gateway between one world and the next,” it is necessary to take stock of the present moment. In March 2020, the National Center on Advancing Person-Centered Practices and Systems (NCAPPS) began gathering information in real time from disabled people,1 providers of disability services, researchers, and other system partners regarding the importance of person-centered practices in times of crisis. Hearing directly about these experiences enlightens us about current realities while simultaneously highlighting potential paths forward.

In this article, members of the NCAPPS community—which includes people with disabilities as well as people presently without disabilities—offer a summary of these lessons. We discuss the individual, systemic, and collective challenges and opportunities presented by the pandemic, based on personal reflections solicited by NCAPPS and submitted as short videos by 16 NCAPPS collaborators during the first 6 months of the pandemic. These personal reflections came from people with disabilities, service providers, researchers, and person-centered planning experts (see the appendix for their names, affiliations, and brief biographies). This “Pandemic Wisdom” series has been publicly released and shared through the NCAPPS website and social media channels throughout 2020. In our content analysis of the video transcripts, person-centered practices emerge as an “anchor” to keep us steady while we cope with the challenges brought on by the pandemic, and a “beacon” to illuminate the path forward for those who seek to (re)establish more person-centered and equitable human service systems in the future.

In March 2020, as the severity of the COVID-19 pandemic became clear, there was immediate concern within the disability community about the ways that disruptions caused by the pandemic would put us/them2 at risk. As case numbers swelled, professionals and advocates raised concerns about governmental guidelines and the potential for medical rationing on the basis of disability (Andrews & Rogers, 2020). At the same time, professionals in the mental health community expressed concerns about how the pandemic would be especially stressful and traumatic for people with disabilities (Lund et al., 2020). Service providers and disabled people alike compiled long lists of these concerns, ranging from the everyday difficulties of communicating about the importance of masks, to concerns about medication supplies, to unmet health care needs (Tromans et al., 2020). Some researchers have argued the pandemic merely highlights long-standing weaknesses in our existing systems for providing supports to people with disabilities, and thus advocated for changes to make these systems more agile, responsive, and safe (Bradley, 2020).

As communities and human service systems moved to enact policies and processes to respond to the pandemic, these changes prompted concerns that people with disabilities would be disproportionately impacted by the resulting staffing shortages and limitations on physical contact or proximity, and by support systems lacking the flexibility to accommodate the shifting environment and needs of all people.

In light of these concerns, NCAPPS sought to contribute knowledge and strategies to support disabled people and the families of people with disabilities. NCAPPS support activities took many forms, including development and compilation of COVID-specific resources (https://ncapps.acl.gov/covid-19-resources.html), adjustments to technical assistance approaches to support states to continue their systems change efforts (Croft et al., 2020), and creation of the “Pandemic Wisdom” series of short videos. In the Pandemic Wisdom videos, the focus of the present paper, subject-matter experts provided diverse perspectives and insights on how person-centered approaches can be used to solve problems, make use of existing resources, and prepare people and systems for new challenges that may emerge.

This study presents common themes in a series of 16 videos solicited by NCAPPS from subject matter experts with professional and lived experience of disability and human service systems. The themes were established using content analysis of video transcripts (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005; Pope et al., 2000). Content analysis is a method of systematically analyzing text data to identify themes to provide deeper knowledge of a topic (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Although it is not a participatory action research study, the work was informed by participatory action approaches. The community under study (in this case, people with disabilities and other experts with experience of long-term support service systems) were invited to be part of the team that developed questions, gathered data, analyzed and interpreted the video transcripts, and wrote this manuscript (Cashman et al., 2008; Greenwood et al., 1993). Of the 16 experts featured in the videos, 8 elected to participate in the creation of this manuscript.

Our analysis illuminates the role and importance of person-centered practices—such as person-centered planning, peer support, and self-direction—in the lives of people with disabilities and those who support disabled people as they navigate the unforeseen pandemic. The impact of COVID-19 is expansive. The pandemic directly affects individual people, the service systems, and the larger society. People and systems interact in dynamic ways. The social ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1977)—which organizes factors at multiple nested levels (e.g., individual, community, society) and allows for examination of the interplay of factors between those levels—provided a structure for organizing the themes that emerged from the videos.

Methods

Recruitment Process and Participants

At the start of the Pandemic Wisdom project, NCAPPS staff (AB, BC, CB, and MK) wrote a letter explaining the purpose and vision of the project and requested recipients to consider participating by submitting a video answering all or any of the following questions.

- What do person-centered thinking, planning, and practices look like in times of crisis?

- How do we hold on to—and even promote—person-centered thinking, planning, and practices at this time?

- How do we balance collective public health with person-centered, individual well-being?

- What lessons can we apply from person-centered thinking, planning, and practices to get through this pandemic?

The letter indicated that participation was voluntary, that there would be no compensation for participation, and that the videos would be shared on the NCAPPS website and social media platforms. The letter also included tips and guidelines on how to record the videos. NCAPPS staff also offered to provide filming support if needed. NCAPPS staff then sent the letter via email to 37 people between March 2020 and September 2020. The 37 people were chosen because they are members of the NCAPPS Person-Centered Advisory and Leadership (PAL) Group; had been involved with NCAPPS as subject matter experts for technical assistance efforts or webinars; or served as faculty for NCAPPS’ Brain Injury Learning Collaborative. Each email addressed the recipient personally by their first name, and one of the NCAPPS staff sent at least one follow-up email. Of the 37 people who received the request, 16 people contributed to the project. The 16 people have various professional backgrounds and lived experiences—ranging from people with disabilities who are involved in advocacy work, service providers, researchers, and person-centered planning experts. The table in the Appendix provides the name, affiliation, and biographic information of the subject matter experts who created Pandemic Wisdom videos.

Data

Video transcripts from the 16 NCAPPS Pandemic Wisdom Shorts served as the data for this analysis. Videos were transcribed using Otter.ai. The transcripts were then reviewed and edited by NCAPPS team members. All videos and transcripts are publicly available at https://ncapps.acl.gov.

Analysis

The analytic process was adapted from the Pope et al. (2002) content analysis method and consisted of six steps: (1) Familiarization, (2) Identifying a Thematic Framework, (3) Sorting, (4) Mapping and Interpretation, (5) Writing, and (6) Reviewing and Refinement.

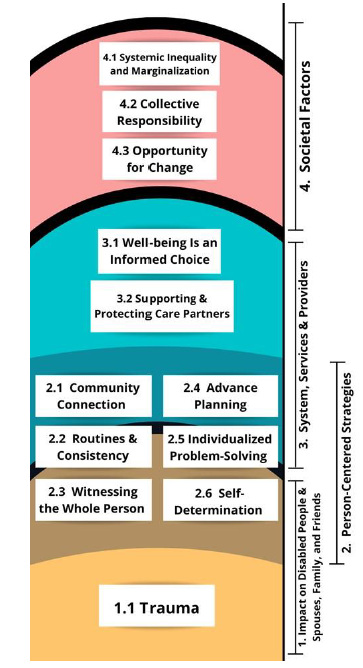

In the first step (familiarization), nine team members (BC, CB, CS, MB, MFS, MK, NL, KL, SR) read through all transcripts and were instructed to list what they saw as themes that appeared across the data. This process resulted in nine lists, each containing 9 to 39 potential themes. To initiate the second step (identifying a thematic framework), one team member (CB) compiled all identified themes into a spreadsheet and created an initial set of thematic groupings. Then, five team members (AB, BC, CB, CS, MK) engaged in two hour-long working meetings to discuss the thematic groupings and arrive at an initial framework consisting of 17 themes. Two other team members (KH and SR) reviewed the initial thematic framework to provide impressions, comments, and suggestions for revision. Team members identified Bronfenbrenner’s social ecological framework as useful for structuring the themes. During the third step (sorting), six team members (AB, CB, MB, BC, MFS, and MK) coded all lines of text using the draft thematic framework using an Excel spreadsheet. After an initial meeting to share impressions and experiences from the coding process, the six team members identified candidate themes for condensing and revising, resulting in a final framework of 12 themes. To prepare for the fourth step (mapping and interpretation), team members reorganized all lines of text by theme. After reading through the reorganized data, six team members (CB, BC, KH, MK, KL, SR) met to discuss relationships between the themes, points of agreement and disagreement, and lessons that we may draw from the data. Another team member (MFS) provided written reflections. The team created a graphic (Figure 1) depicting nested levels, with themes arranged within or across levels. Finally, the team wrote and revised the manuscript using a collaborative, iterative process. Individual team members first wrote specific sections, then other team members reviewed and provided comments and edits to drafts.

Organization of Pandemic Wisdom Themes at Four Levels

Results

The social ecological model informed the organization of themes to identify both specific factors within each of the levels and the interplay between each of the factors or levels (Bronfenbrenner, 1977). For this paper, we created a four-level model: (1) individual disabled people and spouses, family, and friends;3 (2) person-centered strategies employed by disabled people with support from spouses, family, friends, and service providers; (3) systems, services, and providers; and (4) society (Figure 1). We have nested the themes across these four levels to illustrate that themes at the outer levels (e.g., system, society) ultimately impact those at the inner levels, and always impact individual people with disabilities. The first grouping involves people with disabilities and the friends and families of people with disabilities. It contains one theme. The second grouping, which has the greatest concentration of themes, concerns strategies and considerations that are undertaken by disabled people and the supporters of people with disabilities. The third grouping contains themes related to systems considerations. The fourth grouping contains themes at the societal level.

The themes discussed below were primarily identified based on the number of instances that a theme appeared in the video content and the number of speakers for whom the theme was observed. All of the themes identified appeared across a significant number of the individual videos—at least 6, and as many as 11 of the 16 total. Each theme is framed in the discussion below by a single illustrative quote; however, each theme appears many more times both within the referenced video and across the other videos in the series.

Level 1: Impact on Disabled People and Spouses, Family, and Friends

The overarching theme throughout the videos was trauma. Ideas related to trauma appeared in many of the phrases and words the commentators used to describe the impact of COVID-19 on disabled people and the friends and family who make up their/our circles of support. This level reflects how people with disabilities are nested within the other levels of the environment and highlights how trauma was the interconnecting factor across all levels.

Theme 1.1: Trauma

Nearly every commentator discussed one or more of the negative effects the pandemic has had on the lives of disabled people and their/our friends and family. The pandemic has caused fear, grief, uncertainty, disruption, and social isolation—and all of these experiences are traumatizing. Martha Barbone, a certified peer specialist and advocate who has lived experience in the mental health system, said “[Fear] has the power to deeply disturb and limit us. Worst of all, fear can erode our trust in ourselves, in the goodness of others, and in the joy of living.” Several commentators framed their distressing pandemic-related experiences as losses and said that coming to terms with the traumatic experiences will be a lengthy process requiring care and support.

Level 2: Person-Centered Strategies

At this level, themes focused on the interactions, direct practices, and strategies between people with disabilities and those who support them/us. Our team identified six themes at this level.

Theme 2.1: Community Connection

As a response to the trauma of social isolation affecting many people with disabilities, some commentators emphasized the importance of community connections. Person-centered practices are founded in the belief that connection, communication, and relationships are necessary for thriving. Positive connections to supporters (both paid and unpaid) are valuable and give people power. Commentators noted that rebuilding and strengthening community connections should be prioritized by people providing supports, and they described additional ways to establish connections during the pandemic. Janis Tondora, a nondisabled researcher with expertise in mental health recovery supports, highlighted that these connections often take the form of giving as well as receiving support:

In many cases those strategies include finding meaningful ways to connect and give back to others. And, despite our physical distance, COVID-19 has certainly presented a wide range of ways for people to do just that. I hear stories every day of people grocery shopping for elderly neighbors, making masks for healthcare workers, or simply checking in on a friend that they know is having a hard time. In these simple acts of connection people are at once finding ways to serve others while also building their own sense of agency and value.

Theme 2.2: Routines and Consistency

Reestablishing routines and consistency despite the current uncertainty is another strategy that builds on existing person-centered practices to counter the traumatizing effects of the pandemic. Routines that disabled people have chosen for themselves/ourselves gives them/us a sense of grounding and helps to retain their/our self-determination. Predictable routines can also make things easier: people may not have to think or work as hard just to accomplish basic life tasks. Person-centered planning provides a way to reestablish routines and regain consistency. Anntionete Morgan, an experienced person-centered thinking trainer who became sick with COVID, noted that routines can allow us to “[keep] some sort of control over our lives during a time where it seems like we have none, [in] which we’re scared, [and] some of us are sick.”

Theme 2.3: Witnessing the Whole Person

While the pandemic’s effects can be isolating and traumatizing, it can also be isolating and traumatizing for people to interact with a service system that does not recognize or honor their culture or values. A number of the commentators described how these systems fail to acknowledge and address culture—despite the critical importance of doing so. They argued that it is essential for service providers to listen with compassion and respect, and seek to understand disabled people’s experiences, values, and culture—even and especially if it is uncomfortable. Eric Washington, an advocate and brain injury survivor who is Black, provided a succinct example of this theme: “So, if you’re culturally uncomfortable having certain conversations, can you truly be person-centered?” In addition to attending to cultural differences, experts spoke to the importance of providing information—particularly medical information—in formats that are clear and accessible to people with language-related or cognitive disabilities and people who are not fluent in English.

Theme 2.4: Advance Planning

Experts highlighted the value of planning for crises in advance and described ways in which person-centered planning helps to do that. While no one can predict every possible crisis, experts stressed the importance of putting systems in place to manage known uncertainties. They endorsed the value of advance planning to reduce anxiety and minimize the negative impacts of future emergencies. Nicole LeBlanc, an autistic disability advocate, said,

This crisis shows why we need to devote much more effort in supporting adults with disabilities to prepare for emergencies and ensure that the community can accommodate our needs during a major crisis.

Theme 2.5: Individualized Problem-Solving

Because of the way life has changed for all people during the pandemic, disabled people and service provision organizations alike have had to figure out new ways to handle formerly easy tasks and processes. Because supporting self-determination is the end goal of person-centered practice, many kinds of person-centered practices are designed to provide tools or frameworks for people with disabilities—with support as needed—to make decisions for themselves/ourselves. The current uncertainties mean these kinds of practices are especially valuable right now. Problem-solving involves creativity and adaptability to meet individualized and changing needs. It should be expansive and collaborative, incorporating different kinds of options including paid and unpaid supports, technology, and more. Michelle Reynolds, a nondisabled family advocate and researcher, said,

[Person-centered practice] helps ground us in the day-to-day problem-solving we can make about anything that’s happening in our lives. It gives us an opportunity to calm down, recognize the value of the voice, and understand what that person wants.

Theme 2.6: Self-Determination

The remarks on the theme of self-determination often reflected fear that the pandemic would induce changes that unnecessarily limit choices for and the autonomy of people with disabilities. Experts stressed that self-direction and person-driven approaches that promote choice and autonomy are all especially necessary right now. Each disabled person is the expert on their own life and should make their own decisions. Marian Frattarola-Saulino, a nondisabled founder of a community-services provider organization, noted:

Person-centered thinking, planning and practice are means to an end—the end being one that is determined by the person accepting support, who is, as we all are, the expert of their own life. What holds true during this time of COVID-19 is what matters at any other time and in any other context: the amount of control a person has over their own life, not just their planning and their services.

Level 3: Systems, Services, and Providers

The two themes in the third level—which relates to systems considerations—center on the ways in which disability or long-term services and supports (LTSS) systems are organized and how they affect disabled peoples’ experiences during the pandemic.

Theme 3.1: Well-Being Is an Informed Choice

Many commentators noted that there has been a shift in the balance of what is important to and important for disabled people and the people who support them/us during the pandemic. Because of the heightened focus on physical health and safety (factors that are “important for” disabled people), many have experienced extreme restrictions on activities that give their lives meaning and purpose (things that are “important to” disabled people). When these two focuses are out of balance, we undermine self-determination and risk. Or, as Diana Blackwelder, a volunteer researcher and advocate with dementia, put it: “sacrificing the person in order to keep the body alive.” Experts described how the pandemic has highlighted the importance of viewing outcomes through a person-centered lens and beyond the narrow scope of physical health, as well as the importance of promoting dignity of risk and informed choice. Blackwelder asserted her right to this autonomy.

I should be the one making the decisions…. What kind of care do I want to receive? At what point in my life would I prefer to take on additional risk of injury, to include death, if that meant continuing to live the life I want to live?

Theme 3.2: Supporting and Protecting the Care Partners

Another theme involved supporting and protecting people who provide care and support to people with disabilities from the impact and trauma of COVID-19. These include direct support providers, family members, and others who provide paid and unpaid supports (referred to here as “care partners”). Experts recognized that many people who provide paid support and care are people of color and people with lower socioeconomic status, and that they experience disproportionate impacts from the pandemic. Thus, Lydia X. Z. Brown, a disabled advocate, organizer, strategist, and attorney, stressed that it is important to

…protect and ensure fair working conditions for the people that are providing these types of services, many of whom are often disabled themselves, often low income, immigrants, and/or people of color.

In this way, systems of support must not only support the person with a disability but also those people that the person with a disability relies on for their well-being.

Notably, self-direction is one avenue for facilitating access to needed services and supports. In self-direction, the disabled person decides how to structure their/our own home and community-based services by hiring their/our own staff, and in some cases managing a budget that can be used for a range of goods and services (Mahoney, 2020). People who are self-directing have the freedom to compensate care partners—including spouses, friends, and family members—who may be providing critical support in the absence of direct-support professionals. Kevin Mahoney, a nondisabled self-direction researcher, emphasized that with self-direction, “you have a way to receive care from people and provide them something in return.”

Level 4: Societal Factors

The final three themes reflect the opportunities and barriers within society that have come about because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Theme 4.1: Systemic Inequality and Marginalization

Many commentators reflected on systemic inequalities, injustices, and marginalization based on people’s social identities such as race and disability, which the pandemic has deepened and exacerbated. According to Janis Tondora:

The crisis and our country’s response to it have laid bare structural inequities—with the virus hitting certain communities particularly hard. Whether you are a person who is homeless and you can’t get a COVID test because you lack an address or a cell phone, or a person with a disability who may be in need of critical care who needs to worry about medical rationing of ventilators, or a person with a mental illness confined to a psychiatric hospital who has absolutely no control of the six feet of physical space around them, or a person of color who lives each day in fear knowing that they are more than twice as likely to die from the virus should they contract it. In all of these situations, COVID-19 has reminded us that the playing field is not level.

Experts cautioned that some people’s lives are seen as having less value than others, and that policymakers are reducing people to statistics during the period of crisis. While this dynamic is not new, the COVID-19 pandemic has sharpened this reality. Tondora insisted,

If our goal in person-centered systems is to help all people live a good life in their chosen community, we cannot remain silent in the face of these injustices.

Theme 4.2: Collective Responsibility

Collective responsibility emerged as a theme that offers a method of correcting systemic inequalities, injustices, and marginalization. Commentators spoke about the importance of shared responsibilities and working to make sure no one gets left behind. These responsibilities encompass those between and among the various levels (see Figure 1), including disabled people, their service providers, and the government entities that fund and regulate services. These responsibilities include communicating accurate information honestly and in accessible ways so that all can be included, specifically those who use alternative communication methods. We all hold responsibility for sharing our expertise to protect each other and to ensure access to emergency planning and preparedness, and community resources, not just specialized services, for the greater community. These responsibilities highlight the importance of our interdependence as well as mutual respect and accountability for each other’s actions. Shain Neumeier, a disabled lawyer, activist, and community organizer, stated:

It would be a mistake to pretend like collective care and person-centered care are a big dichotomy or somehow in opposition to one another because the collective is made out of all of us. The collective loses something when it loses any one of its members, so we can’t be forgetting right now that every one of those members matters.

Experts emphasized that by focusing on the whole of society, we can emerge whole from the crisis with our shared values intact—meaning that everyone has the inherent right to self-determination, that each of us has control over our lives and over the support we want to make informed decisions that affect our lives, such as where and with whom we live; that each of us is afforded the dignity of risk, and that we are all free to contribute to our chosen communities in ways that are meaningful to us; that each of us is treated equitably, and has equal access to resources such as technology and health care.

Theme 4.3: Opportunity for Change

Finally, commentators expressed hope that the pandemic presents an opportunity for positive change, innovation, and long-awaited reforms. They mentioned a wide range of areas for change, including moving away from institutional and congregate care, providing a greater level of flexibility in employment, promoting self-direction, expanding telehealth and tele-support, and collecting data to document lessons learned. Moreover, commentators expressed an urgency for policymakers, service providers, and advocates to act on the opportunities presented by the pandemic. Marian Frattarola-Saulino, a nondisabled founder of a community-services provider organization, described the opportunity for change this way:

We need to see this as an opportunity to overcome the institutionalized resistance to person-directed, family-centered supports, and enable everyone using services to be healthier and safer, not just in times of public health crisis, but every day. This opportunity must become the mandate to shift the system. What else do we need to convince us that in no other time is the use of person-centered approaches more impactful and necessary? If not now, then when?

Discussion

Analysis of the NCAPPS Pandemic Wisdom Shorts videos revealed 12 themes across four nested levels that we aligned within a framework informed by the social ecological model. These themes highlight critical aspects of person-centered practices and provide important guidance for transformational change for systems, policy, and practices.

Trauma was the overarching theme in all of the video submissions. The COVID-19 pandemic undoubtedly has traumatized everyone in many ways. However, commentators described the ways in which many people with disabilities face heightened challenges. Challenges included not only the health ramifications of the virus but also the impact of social isolation, disruptions in day-to-day routines, and decreased access to needed supports and services. Additionally, many people with disabilities have lost jobs and access to activities in the community that enabled meaningful connection to community. The isolation and exclusion experienced by many disabled people during this time will have far-reaching and long-lasting negative effects.

Equally important, however, is the commentators’ assertions that person-centered practices such as person-centered planning, peer support, and self-direction, enable us to respond to and cope with the traumas caused by the pandemic. The themes that emerged at the second and third levels illuminate ways in which the commentators have been using person-centered principles to mitigate trauma and their desire to incorporate person-centered principles for a better future after the pandemic.

Necessary public health and safety measures related to the pandemic only highlight the need to advocate for the self-determination of disabled people. All commentators—as well as the authors of this paper, a group that includes people with disabilities—agreed that all people must have control over their lives, and that service providers must respect people with disabilities as the experts on our/their own experiences who know best what we/they need. Taken further, some participants pointed out that people who lead more self-determined lives are actually safer from at least some of the negative impacts of the pandemic because they live independently (as opposed to living in congregate settings). Living independently gives people with disabilities more capacity to structure their lives in ways that can mitigate the trauma and social isolation brought on by the pandemic. Through self-direction, disabled people have more flexibility to arrange their/our services and supports to meet unique needs during the pandemic.

Although no one predicted the full scope of the pandemic, having person-centered strategies in place provided a foundation for an immediate response to the changes while ensuring services and supports remained consistent with what was important to the person. Person-centered planning is designed to provide a structure that recognizes disabled people within the context of each individual’s culture, strengths, and relationships, and that provides disabled people with choice and control over services and supports. The pandemic has reinforced the importance of person-centered planning for ensuring choice and control, particularly during emergencies and periods of uncertainty. To be effective, person-centered planning must be flexible, ongoing, and informed by the issues that arise, including the changes to people’s routines and in their lives. Person-centered planning strategies should include a disabled person’s partners, family, friends, and support workers. Additionally, disabled people can make use of modern technology to safely make and sustain social connections.

For many disabled people and care partners, peer support—a practice grounded in person-centered values—has been effective in coping with the traumas associated with the pandemic. Peer support can involve either trained peer specialists working with organizations or informal interactions among others with shared experiences. To harness the benefits of peer supports in the broadest sense, people who provide peer support should be valued for their full lived experience—not just those experiences attributed to a diagnosis. Increasingly, mental health, aging, and other social services professionals recognize the value of connection and support through shared lived experience. Peer support also bridges important gaps in the shared decision-making and informed consent processes by facilitating clear communication using plain, everyday language and accounting for different learning needs and styles. Peer-support providers have been instrumental in the development of self-management and self-directed recovery tools and, during recent months, the use of digital peer support—which is a promising advance in technology (Fortuna et al., 2020). The increasing prominence of peer support during the pandemic is evident in the fact that, in many communities, peer supporters have done outreach and provided connection to those in need, often expanding the scope of services to those who would not have traditionally received peer support (Adams & Rogers, 2020).

At the systems level, the themes revealed clear opportunities for abandoning outdated practices and rebuilding the service system in a more person-centered manner. Thus, the pandemic is not just a calamity but also a potentially transformative moment. Commentators envisioned a system that acknowledges and responds to trauma in the lives of people with disabilities and the paid and unpaid people who support us/them. They/we noted that the pandemic further exacerbated gaps and inequities in our service systems, including disparities in access, utilization, and quality of supports for people of color as well as the unrecognized and undervalued role of direct support professionals as essential workers. They stressed the importance of creating and sustaining systems that attend to equity throughout their practices and policies. Commentators stressed the importance of welcoming every opportunity for change. We must use our time, resources, and information to eliminate systemic inequality and marginalization of disabled people, families of people with disabilities, and the workforce that supports them/us.

Finally, at the societal level, commentators rejected the notion that the health of the individual and of the collective are at odds. Instead, commentators argued that a society that strives for collective responsibility and well-being and leaves no one behind will generate the interdependence necessary to weather disasters like the COVID-19 pandemic. These insights will apply equally well to the current pandemic and future challenges that we may collectively face.

Conclusion

As human service systems throughout the U.S. begin the process of reestablishing themselves in coming years, the Pandemic Wisdom series from the NCAPPS community offers person-centered practices as both an anchor for weathering the pandemic and a beacon for rebuilding lives, service systems, and communities. Through the use of principles of self-determination, equity, and social justice, we may correct long-standing inequities and ensure people with disabilities experience systems as truly person-centered. At the person, provider, system, and societal levels, person-centered practices such as planning, peer support, and self-direction are tools to navigate future disruption and uncertainty.

Of note, the perspectives represented here are those of 16 individual people at one moment in time. A wider array of voices and experiences would have generated even more wisdom. Similarly, though we employed participatory approaches in the data analysis, interpretation and writing for this article, our efforts were limited by time and resource constraints. Additional time and resources would have resulted in a wider and deeper inquiry and more expansive results. Nonetheless, the authors attempted to respond to a pivotal moment in the history of disability and human service systems.

Building on the guidance presented here, future work must explore additional questions related to specific methods for enhancing person-centered thinking, planning, and practice. Critically, leaders in the field must monitor and document their innovations, successes, and failures to continue to expand our knowledge. The unique circumstances we find ourselves in as a society have opened a portal to engage in deep systems change that could result in more person-centered systems for those of us with disabilities.

References

Adams, W., & Rogers, S. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on peer support specialists: Findings from a national survey. Center for Psychiatric Rehabilitation, Boston University: Boston, MA.

Bradley, V. (2020). How COVID-19 may change the world of services to people with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 58(5), 355-360. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33032314/

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1977). Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American Psychologist, 32(7), 513-531. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

Cashman, S. B., Adeky, S., Allen, A. J., Corburn, J., Israel, B. A., Montaño, J., Rafelito, A., Rhodes, S.D., Swanston, S., Wallerstein, N., & Eng, E. (2008). The power and the promise: Working with communities to analyze data, interpret findings, and get to outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 98(8), 1407-1417. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2007.113571

Croft, B., Petner-Arrey, J., & Hiersteiner, D. (2020). Technical assistance needs for realizing person-centered thinking, planning and practices in United States human service systems. Journal of Integrated Care. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1108/JICA-05-2020-0032

Fortuna, K. L., Naslund, J. A., LaCroix, J. M., Bianco, C. L., Brooks, J. M., Zisman-Ilani, Y., Muralidharan, A., & Deegan, P. (2020). Digital peer support mental health interventions for people with a lived experience of a serious mental illness: Systematic review. JMIR Mental Health, 7(4). https://doi.org/10.2196/16460

Greenwood, D. J., Whyte, W. F., & Harkavy, I. (1993). Participatory action research as a process and as a goal. Human Relations, 46(2), 175-192. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F001872679304600203

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277-1288. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1049732305276687

Lund, E. M., Forber-Pratt, A. J., Wilson, C., & Mona, L. R. (2020). The COVID-19 pandemic, stress, and trauma in the disability community: A call to action. Rehabilitation Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/rep0000368

Mahoney, K. (2020). Self-direction of home and community-based services in the time of COVID-19. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 63(6-7), 625-628. Advance online publication. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/01634372.2020.1774833

Pope, C., Ziebland, S., & Mays, N. (2000). Analyzing qualitative data. BMJ, 320(7227), 114-116. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114

Roy, A. (2000). The pandemic is a portal. The Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/10d8f5e8-74eb-11ea-95fe-fcd274e920ca

Tromans, S., Kinney, M., Chester, V., Alexander, R., Roy, A., Sander, J. W., Dudson, H., & Shankar, R. (2020). Priority concerns for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych open, 6(6), e128. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2020.122

Appendix

| Name | Affiliation | Biographic Information |

|---|---|---|

| Martha Barbone | NCAPPS PAL Group | Martha Barbone served in the U.S. Air Force before being sidelined by a diagnosis of depression and PTSD. She has provided peer support on an inpatient unit, in a peer-run organization, directed the Certified Peer Specialist training program, and has worked for the National Association of Peer Supporters. |

| Diana Blackwelder | NCAPPS PAL Group | Diana Blackwelder is a volunteer researcher at the University of Maryland studying technology and dementia, serves on the Dementia Alliance International (DAI) Board of Directors, represents DAI to the Leaders Against Alzheimer’s Disease (LEAD) coalition, is a National Alzheimer’s Association Early Stage Advisor Alumni, and consults to the Smithsonian and US Botanical Garden Access Programs for people living with dementia. |

| Valerie Bradley | Human Services Research Institute | Valerie Bradley is the founder and president emerita of the Human Services Research Institute. With more than 40 years of experience, Val is a nationally recognized expert in the intellectual and developmental disabilities field. She has devoted her career to working with public agencies and other researchers to strengthen services, improve programs, and inform policy—all as an early and staunch advocate for the direct participation of people with disabilities in these efforts. |

| Lydia X. Z. Brown | NCAPPS PAL Group | Lydia X. Z. Brown is a disabled advocate, organizer, strategist, and attorney. For over a decade, their work has focused on interpersonal, institutional, and state violence against multiply- marginalized disabled people, especially at the intersections of race, gender, class, and sexuality. They are core faculty in Georgetown University’s Disability Studies Program and Director of Policy, Advocacy, & External Affairs for the Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network. |

| Marian Frattarola-Saulino | Values into Action | Marian Frattarola-Saulino is the co-founder and CEO of Values Into Action, an organization dedicated to self-direction and co-production of services and supports. Marian is also one of the founders of The Alliance for Citizen Directed Supports, a membership organization led by disabled people and focused on advancing self-direction. |

| Karyn Harvey | Park Ave Group | Karyn Harvey has worked in the field of intellectual disabilities as a psychologist for over 30 years and has published two books on the topic. She is director of programs and training for the Park Ave Group and speaks throughout the country on trauma-informed supports for people with intellectual disabilities. |

| Kelly Lang | NCAPPS PAL Group | Kelly Lang’s brain injury advocacy career began after she and her 3-year-old daughter were injured in a horrific car accident in 2001. Kelly has served on the Board of the Brain Injury Association of Virginia and is a member of the Brain Injury Association of America’s Brain Injury Council. |

| Nicole LeBlanc | Human Services Research Institute | Nicole LeBlanc is the coordinator of the Person-Centered Advisory and Leadership Group (PAL Group) for NCAPPS. Nicole has a keen ability and interest in public policy and excels at communicating the needs of people with developmental disabilities to public officials. |

| Kevin Mahoney | Boston College School of Social Work | Kevin Mahoney is a professor emeritus at Boston College School of Social Work. He is best known for his research on participant direction of home and community-based services and supports for people with disabilities, and financing of long-term care. He serves as the director of the National Resource Center for Participant-Directed Services at Boston College. |

| Anntionete Morgan | NCAPPS PAL Group | Anntionete Morgan is a Certified Person-Centered Thinking Trainer (CPCTT), and has over 17 years of experience as a social worker. Her experience includes behavioral health with an emphasis on substance use, medical discharge planning, HIV case management, service coordination, managed care and clinical training. |

| Shain Neumeier | Committee for Public Counsel Services, Mental Health Litigation Division | Shain M. Neumeier is a lawyer, activist, and community organizer, and an out and proud member of the disabled, trans, queer, and asexual communities. They are a passionate advocate for the autonomy of young, disabled, and queer people, and focus on ending abuse and neglect of disabled youth in schools and treatment facilities. Shain has worked with the Intersex and Genderqueer Recognition Project, the Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network, and the Community Alliance for the Ethical Treatment of Youth. |

| Michele C. Reynolds | University of Missouri, Kansas City | Sheli Reynolds is the associate director at the University of Missouri-Kansas City (UMKC) Institute for Human Development, where she advocates for and alongside people with disabilities and their families, working to create policy, practice, system, and community change. She is the lead developer of the Charting the LifeCourse framework and directs the LifeCourse Nexus. |

| Carole Starr | Brain Injury Voices | Carole Starr has been a brain injury survivor since 1999 when she was in a car accident. The injury ended Carole’s career as an educator and her hobby of classical music performance. One small step at a time, Carole has reinvented herself. She is now a national keynote speaker, the author of To Root & To Rise: Accepting Brain Injury and the founder/facilitator of Brain Injury Voices, an award-winning survivor volunteer group in Maine. |

| Janis Tondora | Yale University School of Medicine | Janis Tondora is a professor and researcher at the Yale University School of Medicine whose work focuses on services that promote self-determination, recovery, and community inclusion among individuals diagnosed with serious behavioral health disorders. |

| Eric Washington | Brain Injury Association of Missouri | Eric Washington is a former football player for the University of Kansas. His football career ended on September 30, 2006 due to a concussion and spinal cord injury. After recovering from the neck injury, he returned to graduate with a bachelor’s degree in Applied Behavioral Sciences. Today, Eric’s life mission is to advocate for people like him – people with TBI, especially those who are also homeless. |

| Janet Williams | Minds Matter LLC | Janet Williams has been working for people with brain injuries and families since 1982. She is the founder of Minds Matter LLC, an organization grounded in person-centered practices that provides supports to people with brain injury. |