Research as inquiry: Framing questions & finding sources

9 Getting started on research

Christian J. Pulver and Marisa Yerace

9.1 Everyday Research

We rarely call what we do every day “research,” but when we go online to search for news and information, we are engaging in everyday research. Everyday research has become a basic skill as the internet has expanded in scale and speed. In many cases, when we search for information, we want to understand a “problem” we’ve encountered—to search for medical advice about a sore throat we have, or to learn more about a product we want to buy. We’ll read articles, reviews, and watch videos; we’ll compare brands and prices. Indeed, whether we’re trying to diagnose why we’re feeling sick or trying to understand why our phone’s battery won’t hold a charge, the first place we usually turn to is the internet to help solve the problem. Of course, this kind of everyday research is just one kind of information seeking, but it’s a good place to begin when starting a larger research endeavor to write about a problem that matters to academic, professional, and public audiences. In this course you’ll build on these everyday research skills to develop more formal academic research strategies for collecting your own data and finding, evaluating, and selecting sources.

To be sure, problems come in all shapes and sizes, from minor to major, including “wicked problems.” Wicked problems are problems “with many interdependent factors making them seem impossible to solve… the factors are often incomplete, in flux, and difficult to define.”[1] Such problems, due to their far-reaching effects and the tensions they can cause among people and groups, require a more intentional and formal approach to their study. As your own inquiry into a problem takes a more formal shape, the standards and ethical expectations grow for how the research is conducted, how data is collected, and the credibility of the sources you draw on.

9.2 Identifying and Exploring a Wicked Problem

When first inquiring about a problem you’re interested in, a general internet search is a good start. Visiting Wikipedia, reading popular articles, and watching media related to the problem will help build your understanding of the discourse that surrounds the problem—how others are talking about it, different sides of the issue, and its history and context. Since these early stages are exploratory, you’ll want to keep an open mind and slow down as you research. As you dig deeper into a problem, the more complicated and nuanced it will become.

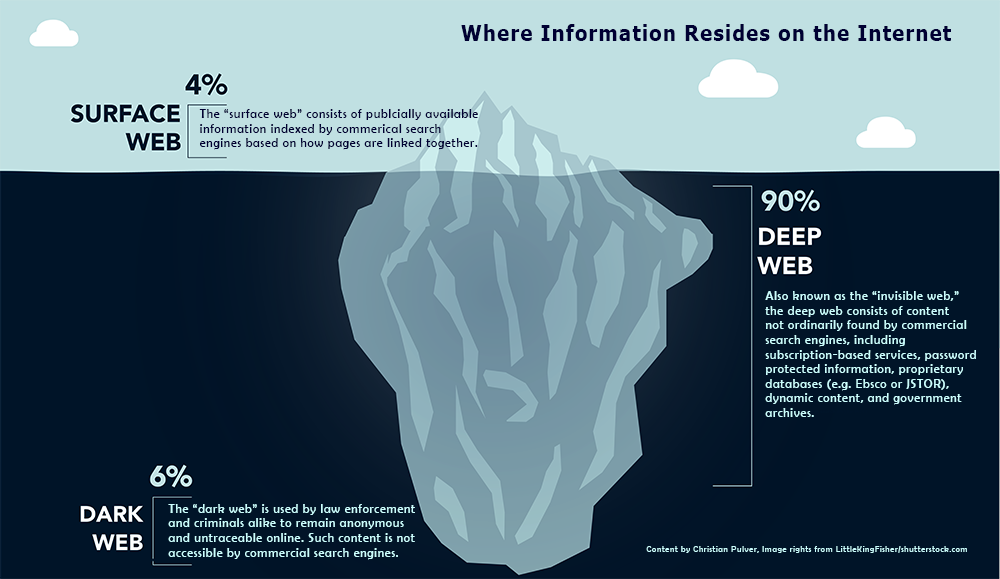

Google, Bing, and other commercial search engines are useful tools for everyday research and you’ll use these throughout the research process. Keep in mind though, they have their limitations and generally they are not enough for researching a wicked problem. In fact, when we use Google or any other commercial search engine, we really only have access to about 4% of the information that circulates on the internet.[2]

When studying a difficult problem, curious researchers have to go beyond the surface web and commercial search engines to build a deeper understanding of the problem they’re researching. Understanding a problem at a deeper level means accessing sources that are often password protected or require subscriptions to enter—academic databases, government archives, scientific reports, legal documents, and other sources that commercial search engines may not have access to. While commercial search engines are always improving and finding more resources on the deep web (Google Scholar, for example), they usually just point to where a resource is located rather than providing access to the resource. From a researchers perspective, the main thing to keep in mind about the deep web is that commercial search engines are limited in their scope. Not only are they unable to find and index the majority of the information that exists on the global internet, the way they filter and personalize searching based on our previous searches, and the way they rank search results, all narrow what we see and limit our access to a wider variety of information. Researching a wicked problem will require a dive into the deep web and the use of more sophisticated research strategies that include using more precise search terms and using specialized databases for scholarly research, government archives, and industry/trade publications.

These kinds of sources, whether on the surface or deep web, are secondary data or secondary research. Secondary data are texts and research that has been created by others who are also interested in some facet of the problem you are looking into. Articles, essays, research reports, documentaries—any source you use that has been composed by someone else is a secondary source of data.

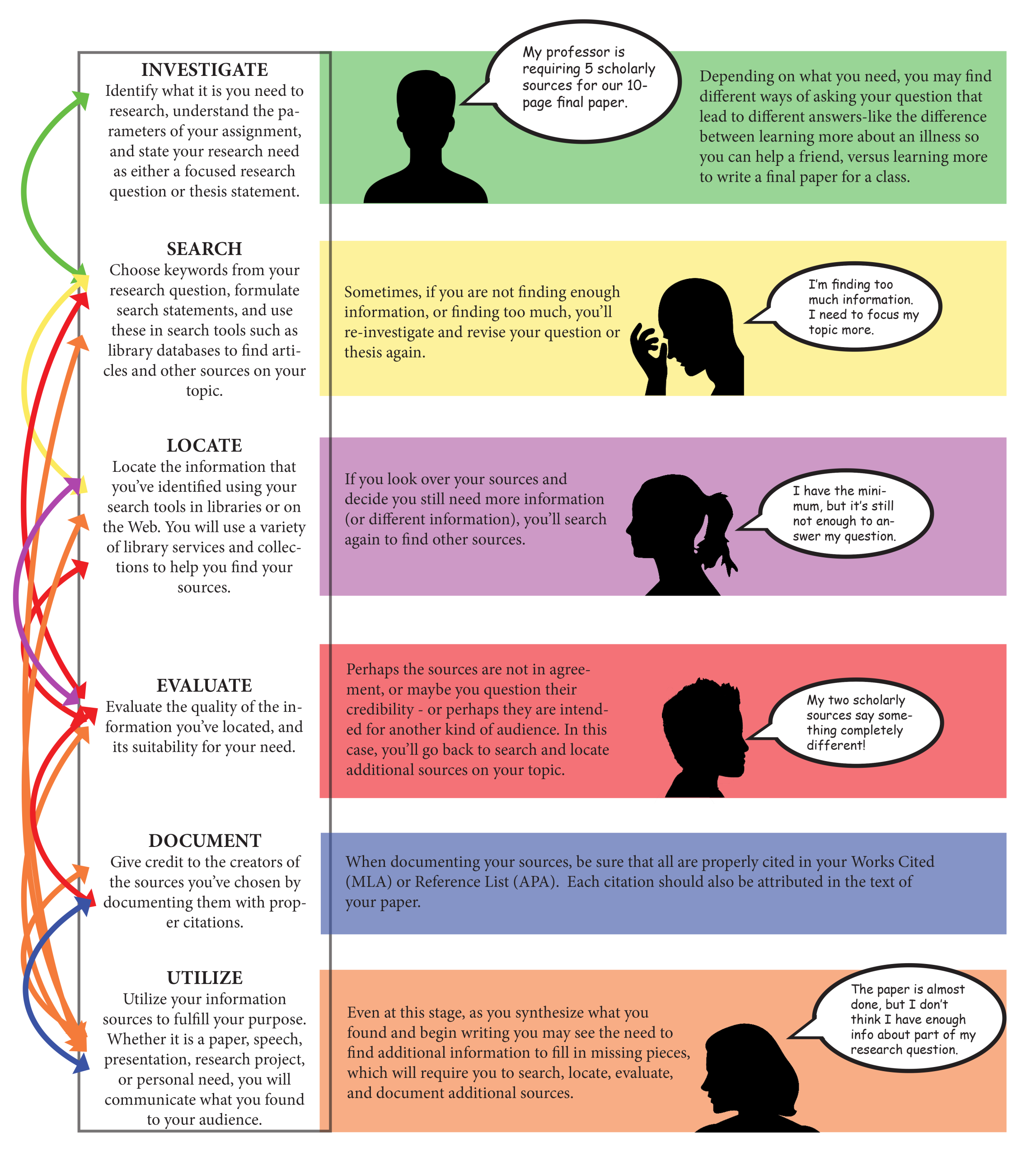

Like we said in Chapter 8, think about research as a recursive process—a lot like writing!—where you may have to repeat steps, adjust your goals, and re-evaluate your approach.

9.2.1 Where to Find Credible Secondary Sources on the Deep Web

- Google Scholar

- Government databases

- Non-profit research organizations (e.g. Pew Research Center or the American Cancer Society)

- Library catalogues and research databases

Image descriptions

Figure 8 image description: A metaphorical iceberg of information. The section above water is labeled the “surface web” and only represents 4% of the iceberg–this “consists of publicly available information indexed by commercial search engines;” 90% of what is underwater is the “deep web,” or “the invisible web,” with “content not normally found by commercial search engines” and which may be behind a paywall; with the remaining 6% as the “dark web,” not accessible via search engines and used by law enforcement and criminals “to remain anonymous and untraceable online.” Content by Christian Pulver; figure from Thinking rhetorically.

Figure 9 image description: Six steps of the research process are identified and described:

- Investigate: Identify what it is you need to research, understand the parameters of your assignment, and state your research need as either a focused research question or thesis statement. Depending on what you need, you may find different ways of asking your question that lead to different answers–like the difference between learning more about an illness so you can help a friend, versus learning more to write a final paper for a class.

- Search: Choose keywords from your research question, formulate search statements, and use these in search tools such as library databases to find articles and other sources on your topic. Sometimes, if you are not finding enough information, or finding too much, you’ll re-investigate and revise your question or thesis again.

- Locate: Locate the information that you’ve identified using your search tools in libraries or on the Web. You will use a variety of library services and collections to help you find your sources.

- Evaluate: Evaluate the quality of the information you’ve located, and its suitability for your need. Perhaps the sources are not in agreement, or maybe you question their credibility–or perhaps they are intended for another kind of audience. In this case, you’ll go back to search and locate additional sources on your topic.

- Document: Give credit to the creators of the sources you’ve chosen by documenting them with proper citations. When documenting your sources, be sure that all are properly cited in your Works Cited (MLA) or Reference List (APA). Each citation should also be attributed in the text of your paper.

- Utilize: Utilize your information sources to fulfill your purpose. Whether it is a paper, speech, presentation, research project, or personal need, you will communicate what you found to your audience. Even at this stage, as you synthesize what you found and begin writing you may see the need to find additional information to fill in missing pieces, which will require you to search, locate, evaluate, and document additional sources.

Arrows bounce around between steps, showing that this process is not linear. Figure from Chapter 2 of Information Navigator, Adamson et al., CC-BY-NC-SA.

- Interaction Design Foundation. ↵

- Devine, Jane, and Francine Egger-Sider. Going beyond Google Again: Strategies for Using and Teaching the Invisible Web. Neal-Schuman, 2014. ↵