Reflection and Lifelong Learning: The Value of Writing in Your Academic and Professional Journey

20 Reflection

Christine Jones; Daryl Smith O'Hare; and Marisa Yerace

Sometimes the process of figuring out who you are as writers requires reflection, a “looking back” to determine what you were thinking and how your thinking changed over time, relative to key experiences.[1] Mature learners set goals and achieve them by charting a course of action and making adjustments along the way when they encounter obstacles. They also build on strengths and seek reinforcement when weaknesses surface. What makes them mature? They’re not afraid to make mistakes (own them even), and they know that struggle can be a rewarding part of the process. By equal measure, mature learners celebrate their strengths and use them strategically. By adopting a reflective position, they can pinpoint areas that work well and areas that require further help—and all of this without losing sight of their goals.

Student reflection about their thinking is such a crucial part of the learning process. You have come to this course with your own writing goals. Now is a good time to think back on your writing practices with reflective writing, also called metacognitive writing. Reflective writing helps you think through and develop your intentions as a writer. Leveraging reflective writing also creates learning habits that extend to any discipline of learning. It’s a set of procedures that helps you step back from the work you have done and ask a series of questions: Is this really what I wanted to do? Is this really what I wanted to say? Is this the best way to communicate my intentions? Reflective writing helps you authenticate your intentions and start identifying places where you either hit the target or miss the mark. You may find, also, that when you communicate your struggles, you can ask others for help! Reflective writing helps you trace and articulate the patterns you have developed, and it fosters independence from relying too heavily on an instructor to tell you what you are doing.

Throughout this course, you have been working toward an authentic voice in your writing. Your reflection on writing should be equally authentic or honest when you look at your purposes for writing and the strategies you have been leveraging all the while.

20.1 Reflective Learning

Reflective thinking is a powerful learning tool. As we have seen throughout this course, proficient readers are reflective readers, constantly stepping back from the learning process to think about their reading. They understand that just as they need to activate prior knowledge at the beginning of a learning task and monitor their progress as they learn, they also need to make time during learning as well as at the end of learning to think about their learning process, to recognize what they have accomplished, how they have accomplished it, and set goals for future learning. This process of “thinking about thinking” is called metacognition. When we think about our thinking—articulating what we now know and how we came to know it—we close the loop in the learning process.

How do we engage in a reflection? Educator Peter Pappas modified Bloom’s Taxonomy of Learning to focus on reflection:

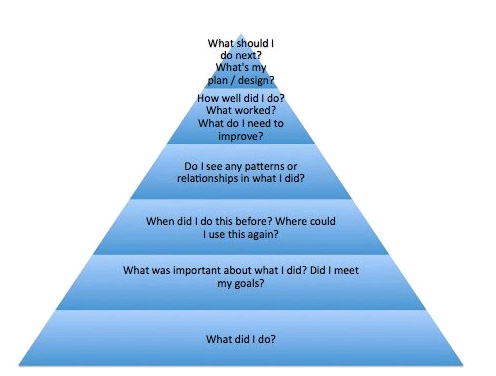

This “taxonomy of reflection” provides a structure for metacognition. Educator Silvia Rosenthal Tolisano has modified Pappas’s taxonomy into a pyramid and expanded upon his reflection questions:

By making reflection a key component of our work, students realize that learning is not always about facts and details. Rather, learning is about discovery.

One of the major goals in any writing class is to encourage students’ growth as writers. No one is expected to be a perfect writer at the end of the semester. Your instructor’s hope, however, is that after 16 weeks of reading, writing, and revising several major essays, you are more confident, capable, and aware of yourself as a writer than you were at the beginning of the semester. Reflecting on the process that you go through as you write – even if your writing is not perfect – can help you to identify the behaviors, strategies, and resources that have helped you to be successful or that could support your future success. In short, reflecting on how you write (or how you have written during a particular semester) can be quite powerful in helping you to identify areas where you have grown and areas where you still have room for more growth.

20.2 The difference from journaling or writing in a diary

If you write in a diary or a journal, recording your thoughts and feelings about what has happened in your life, you are certainly engaging in the act of reflection. Many of us have some experience with this type of writing. In our diaries, journals, or other informal spaces for speaking – or writing– our mind, we write to ourselves, for ourselves, in a space that will largely remain private.

Some classes will ask you to reflect on your writing, and those letters will contain some of those same features:

- The subject of the reflective essay is you and your experiences

- You can generally use the first person in a reflective essay

But writing academic reflections is a bit different from journaling or keeping a diary:

| Personal diary/journal | Reflection essay for a course | |

|---|---|---|

| Audience | Only you will read it! (at least, that is often the intention) | Professor, peers, or others will read your essay. A reflective essay is written with the intention of submitting it to someone else |

| Purpose | To record your emotions, thoughts, analysis; to get a sense of release or freedom to express yourself | To convey your thoughts, emotions, analysis about yourself to your audience, while also answering a specific assignment question or set of questions |

| Structure | Freeform. No one will be reading or grading your diary or journal, so you get to choose organization and structure; you get to choose whether or not the entries are edited | An essay. The reflection should adhere to the style and content your audience would recognize and expect. These would include traditional paragraph structure, a thesis that conveys your essay’s main points, a well-developed body, strong proofreading, and whatever else the assignment requires |

| Development | Since you are only writing for yourself, you can choose how much or how little to elaborate on your ideas | All of the points you make in the essay should be developed and supported using examples or evidence which come from your experiences, your actions, or your work |

20.3 Writing a reflective essay or letter

As with any essay, a reflective essay should come with its own assignment sheet. On that assignment sheet, you should be able to identify what the purpose of the reflective essay is and what the scope of the reflection needs to be. Some key elements of the reflective essay that the assignment sheet should answer are:

- What, exactly, the scope of the reflection is. Are you reflecting on one lesson, one assignment, or the whole semester?

- Do you have detailed guidelines, resources, or reference documents for your reflections that must be met?

- Is there a particular structure for the reflection?

- Should the reflection include any outside resources?

If you are struggling to find the answers to these questions, ask your professor!

20.3.1 Key Features of a Reflection Letter:

- The audience is identified in both the salutation and throughout the body of the paper

- The reflection discusses writing habits and processes

- The reflection discusses challenges

- The reflection addresses course-specific elements

- The reflection discusses Peer Editing or Peer Review

- The letter is in business letter format

Image descriptions

Figure 10 image description: A list of reflective tasks with an arrow pointing from the bottom to the top. From the bottom up, the cells read “Remembering: What did I do?”, “Understanding: What was important about it?”, ‘”Applying: Where could I use this again?”, “Evaluating: How well did I do?”, and “Creating: What should I do next?” An arrow points from the bottom cell up the list to the top cell. Image of Taxonomy, Peter Pappas, http://www.peterpappas.com/images/2011/08/taxonomy-of-reflection.png, CC BY-NC.

Figure 11 image description: Image of a blue pyramid. On each level of the pyramid, from bottom to top, are the labels “What did I do?”, “What was important about what I did? Did I meet my goals?”, “When did I do this before? Where could I use this again?”, “Do I see any patterns or relationships in what I did?”, “How well did I do? What worked? What do I need to improve on?”, and “What should I do next? What’s my plan/design?” Silvia Rosenthal Tolisano, http://langwitches.org/blog/2011/06/20/reflectu00adreflectingu00adreflection/, CC BY-NC-SA.

- Content in this chapter adapted by Jones and O'Hare: from Excelsior Online Writing Lab (OWL), Excelsior College, https://owl.excelsior.edu/, Creative Commons Attribution-4.0 International License; from Composition II, Elisabeth Ellington, Chadron State College, http://www.csc.edu/, Kaleidoscope Open Course Initiative, License: CC BY: Attribution; from A Guide to Rhetoric, Genre, and Success in First-Year Writing, Emilie Zickel, CC-BY-NC-SA; and from Composition II, Alexis McMillan-Clifton, Tacoma Community College, http://www.tacomacc.edu. ↵