The Writing Process: Drafting, Revising, and Reflecting

14 Structuring an essay

Ann Inoshita; Karyl Garland; Kate Sims; Jeanne K. Tsutsui Keuma; Tasha Williams; Amy Guptill; and Marisa Yerace

14.1 Planning Based on Audience and Purpose

Identifying the target audience and purpose of an essay is a critical part of planning the structure and techniques that are best to use. It’s important to consider the following:

- Is the the purpose of the essay to educate, announce, entertain, or persuade?

- Who might be interested in the topic of the essay?

- Who would be impacted by the essay or the information within it?

- What does the reader know about this topic?

- What does the reader need to know in order to understand the essay’s points?

- What kind of hook is necessary to engage the readers and their interest?

- What level of language is required? Words that are too subject-specific may make the writing difficult to grasp for readers unfamiliar with the topic.

- What is an appropriate tone for the topic? A humorous tone that is suitable for an autobiographical, narrative essay may not work for a more serious, persuasive essay.

Hint: Answers to these questions help the writer to make clear decisions about diction (i.e., the choice of words and phrases), form and organization, and the content of the essay.

14.1.1 Use Audience and Purpose to Plan Language

In many classrooms, students may encounter the concept of language in terms of correct versus incorrect. However, we want to approach language from the perspective of appropriateness. Writers should consider that there are different types of communities, each of which may have different perspectives about what is “appropriate language” and each of which may follow different rules–think about our discussion of discourse communities in Chapter 6.

Writers (and readers) may be more familiar with a home community that uses a different language than the language valued by the academic community. For example, many people in Hawai‘i speak Hawai‘i Creole English (HCE colloquially regarded as “Pidgin”), which is different from academic English. This does not mean that one language is better than another or that one community is homogeneous in terms of language use; most people “code-switch” from one “code” (i.e., language or way of speaking) to another. It helps writers to be aware and to use an intersectional lens to understand that while a community may value certain language practices, there are several types of language practices within our community.

What language practices does the academic discourse community value? A common goal of required writing courses is to prepare students to write according to the conventions of academia and Standard American English (SAE). Understanding and adhering to the rules of a different discourse community does not mean that students need to replace or drop their own discourse. You may add to your language repertoire as education continues to transform your experiences with language, both spoken and written. In addition to the linguistic abilities you already possess, you can enhance your academic writing skills for personal growth in order to meet the demands of the working world and to enrich the various communities you belong to. One strategy many use is to freewrite in your own discourse and then use later drafting and revisions to align your discursive choices with your audience’s expectations.

14.2 Moving beyond the five-paragraph theme

You may think that writing longer and more difficult pieces in college means merely extending the five-paragraph structure you may have been taught in high school. The truth is: yes and no. If you’re good at the five-paragraph theme, then you’re good at identifying a clear and consistent thesis, arranging cohesive paragraphs, organizing evidence for key points, and situating an argument within a broader context through the intro and conclusion.

In college you need to build on those essential skills. The five-paragraph theme, as such, is bland and formulaic; it doesn’t compel deep thinking. Your professors are looking for a more ambitious and arguable thesis, a nuanced and compelling argument, and real-life evidence for all key points, all in an organically[1] structured paper.

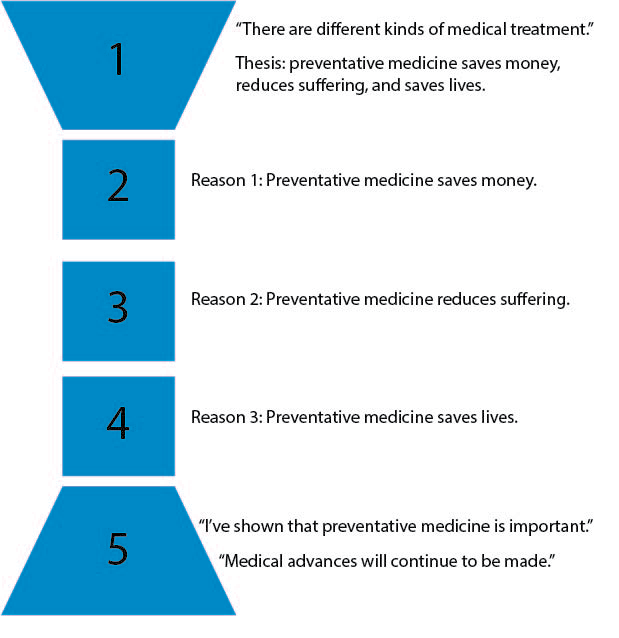

Figures 16.1 and 16.2 contrast the standard five-paragraph theme and the organic college paper. The five-paragraph theme, outlined in Figure 16.1 is probably what you’re used to: the introductory paragraph starts broad and gradually narrows to a thesis, which readers expect to find at the very end of that paragraph. In this idealized format, the thesis invokes the magic number of three: three reasons why a statement is true. Each of those reasons is explained and justified in the three body paragraphs, and then the final paragraph restates the thesis before gradually getting broader. This format is easy for readers to follow, and it helps writers organize their points and the evidence that goes with them. That’s why you learned this format.

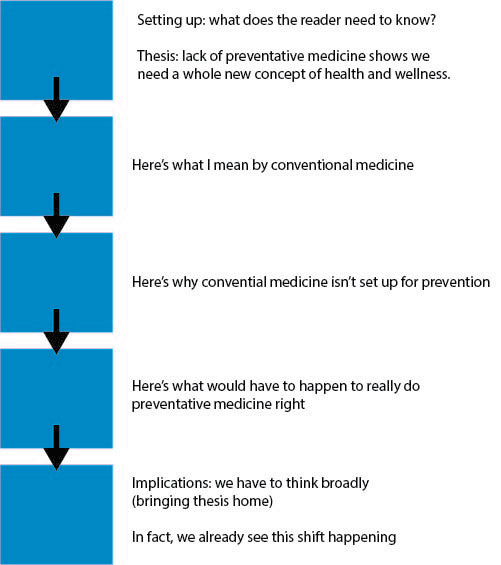

Figure 16.2, in contrast, represents a paper on the same topic that has the more organic form expected in college. The first key difference is the thesis. Rather than simply positing a number of reasons to think that something is true, it puts forward an arguable statement: one with which a reasonable person might disagree. An arguable thesis gives the paper purpose. It surprises readers and draws them in. You hope your reader thinks, “Huh. Why would they come to that conclusion?” and then feels compelled to read on. The body paragraphs, then, build on one another to carry out this ambitious argument. In the classic five-paragraph theme (Figure 16.1) it hardly matters which of the three reasons you explain first or second. In the more organic structure (Figure 16.2) each paragraph specifically leads to the next.

The last key difference is seen in the conclusion. Because the organic essay is driven by an ambitious, non-obvious argument, the reader comes to the concluding section thinking “OK, I’m convinced by the argument. What do you, author, make of it? Why does it matter?” The conclusion of an organically structured paper has a real job to do. It doesn’t just reiterate the thesis; it explains why the thesis matters.

The substantial time you spent mastering the five-paragraph form in Figure 11 was time well spent; it’s hard to imagine anyone succeeding with the more organic form without the organizational skills and habits of mind inherent in the simpler form. But if you assume that you must adhere rigidly to the simpler form, you’re blunting your intellectual ambition. Your professors will not be impressed by obvious theses, loosely related body paragraphs, and repetitive conclusions. They want you to undertake an ambitious independent analysis, one that will yield a thesis that is somewhat surprising and challenging to explain.

14.2.1 Techniques to plan structure

Before writing a first draft, writers find it helpful to begin organizing their ideas into chunks so that they (and readers) can efficiently follow the points as organized in an essay.

First, it’s important to decide whether to organize an essay (or even just a paragraph) according to one of the following:

- Chronological order (organized by time)

- Spatial order (organized by physical space from one end to the other)

- Prioritized order (organized by order of importance)

- There are many ways to plan an essay’s overall structure, including mapping and outlining.

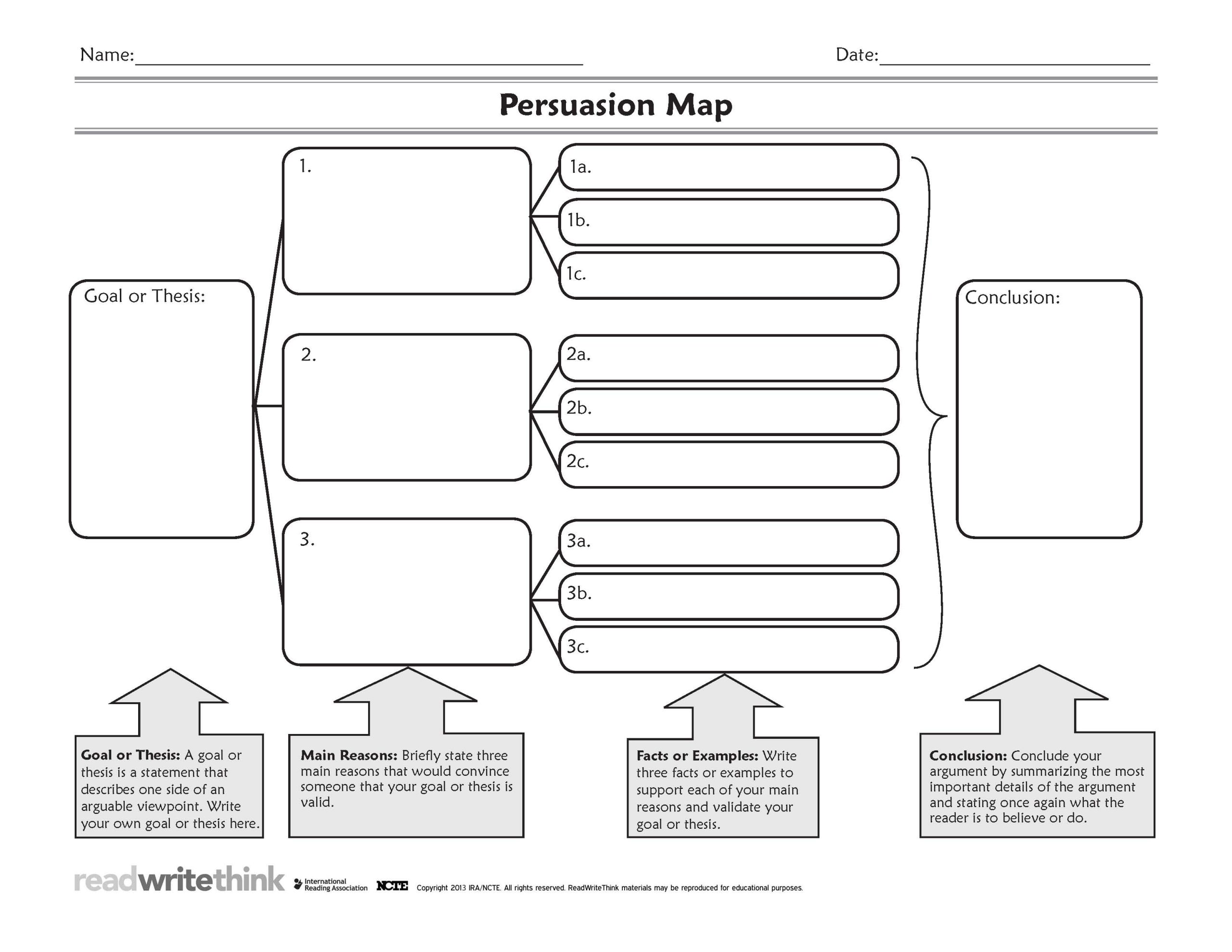

Mapping (which sometimes includes using a graphic organizer) involves organizing the relationships between the topic and other ideas. Figure 16.3 is example (from ReadWriteThink.org, 2013) of a graphic organizer that could be used to write a basic, persuasive essay:

Outlining is also an excellent way to plan how to organize an essay. Formal outlines use levels of notes, with Roman numerals for the top level, followed by capital letters, Arabic numerals, and lowercase letters.

Example Outline

- Introduction

- Hook/Lead/Opener: According to the Leilani was shocked when a letter from Chicago said her “Aloha Poke” restaurant was infringing on a non-Hawaiian Midwest restaurant that had trademarked the words “aloha” (the Hawaiian word for love, compassion, mercy, and other things besides serving as a greeting) and “poke” (a Hawaiian dish of raw fish and seasonings).

- Background information about trademarks, the idea of language as property, the idea of cultural identity, and the question about who owns language and whether it can be owned.

- Thesis Statement (with the main point and previewing key or supporting points that become the topic sentences of the body paragraphs): While some business people use language and trademarks to turn a profit, the nation should consider that language cannot be owned by any one group or individual and that former (or current) imperialist and colonialist nations must consider the impact of their actions on culture and people groups, and legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good of internal peace of the country.

- Body Paragraphs

- Main Point (Topic Sentence): Some business practices involve co-opting languages for the purpose of profit.

- Supporting Detail 1: Information from Book 1—Supporting Sentences

- Subpoint

- Supporting Detail 2: Information from Article 1—Supporting Sentences

- Subpoint

- Subpoint

- Supporting Detail 1: Information from Book 1—Supporting Sentences

- Main Point (Topic Sentence): Language cannot be owned by any one group or individual.

- Supporting Detail 1: Information from Book 1—Supporting Sentences

- Subpoint

- Supporting Detail 2: Information from Article 1—Supporting Sentences

- Subpoint

- Subpoint

- Supporting Detail 1: Information from Book 1—Supporting Sentences

- Main Point (Topic Sentence): Once (or currently) imperialist and colonialist nations must consider the impact of their actions on culture and people groups.

- Supporting Detail

- Subpoint

- Supporting Detail

- Legislators should bar the trademarking of non-English words for the good and internal peace of the country.

- Main Point (Topic Sentence): Some business practices involve co-opting languages for the purpose of profit.

- Conclusion (Revisit the Hook/Lead/Opener, Restate the Thesis, End with a Twist—a strong more globalized statement about why this topic was important to write about)

Note about outlines: Informal outlines can be created using lists with or without bullets. What is important is that main and subpoint ideas are linked and identified.

Image descriptions

Figure 10 image description: The five-paragraph theme visualized with “blocks,” where the top and bottom block (introduction and conclusion) funnel outwards, and the three inner blocks (three points of an argument) are uniform squares. Originally from Writing in college.

Figure 11 image description: Five uniform blocks, representing ideas within a paper, are connected by arrows pointing to the next block down. This is meant to demonstrate a paper that flows organically between connected points. Originally from Writing in college.

Figure 12 image description: A “persuasion map” from WriteReadThink.org. A goal or thesis is split into three parts, then each of those split into three parts, with the argument all leading to one conclusion. Sourced from English composition; originally from ReadWriteThink (NCTE). (Copyright 2013 IRA/NCTE. All rights reserved. ReadWriteThink materials may be reproduced for educational purposes.)

- “Organic” here doesn’t mean “pesticide-free” or containing carbon; it means the paper grows and develops, sort of like a living thing. ↵