6 Life is a Dream

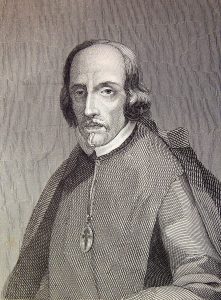

Pedro Calderón de la Barca

Introduction

Life is a Dream (1635) by Pedro Calderón de la Barca (1600-1681)

Pedro Calderón de la Barca is one of Spain’s most famous playwrights. His work contributes to what is called the Spanish Golden Age of Theatre (considered between 1590-1681). He was born in Madrid and spent his life as a soldier, Catholic priest, playwright, poet, and knight of the Order of Santiago. His playwriting built on the work of others including Lope de Vega. He wrote in a variety of styles, but most of his plays focus on themes of love and honor. He wrote over 100 secular “comedias” and 70 auto sacramentales (a form unique to Spain and resemble Medieval morality plays).

His most famous play is Life is a Dream (sometimes written as Life’s a Dream) and has themes of free will vs. fate and honor. There are many adaptations and translations of the play. It was also adapted into an opera (twice!).

Play Text

Introduction

Two of the dramas contained in this volume are the most celebrated of all Calderon’s writings. The first, “La Vida es Sueno”, has been translated into many languages and performed with success on almost every stage in Europe but that of England. So late as the winter of 1866-7, in a Russian version, it drew crowded houses to the great theatre of Moscow; while a few years earlier, as if to give a signal proof of the reality of its title, and that Life was indeed a Dream, the Queen of Sweden expired in the theatre of Stockholm during the performance of “La Vida es Sueno”. In England the play has been much studied for its literary value and the exceeding beauty and lyrical sweetness of some passages; but with the exception of a version by John Oxenford published in “The Monthly Magazine” for 1842, which being in blank verse does not represent the form of the original, no complete translation into English has been attempted. Some scenes translated with considerable elegance in the metre of the original were published by Archbishop Trench in 1856; but these comprised only a portion of the graver division of the drama. The present version of the entire play has been made with the advantages which the author’s long experience in the study and interpretation of Calderon has enabled him to apply to this master-piece of the great Spanish poet. All the forms of verse have been preserved; while the closeness of the translation may be inferred from the fact, that not only the whole play but every speech and fragment of a speech are represented in English in the exact number of lines of the original, without the sacrifice, it is to be hoped, of one important idea.

A note by Hartzenbusch in the last edition of the drama published at Madrid (1872), tells that “La Vida es Sueno”, is founded on a story which turns out to be substantially the same as that with which English students are familiar as the foundation of the famous Induction to the “Taming of the Shrew”. Calderon found it however in a different work from that in which Shakespeare met with it, or rather his predecessor, the anonymous author of “The Taming of a Shrew”, whose work supplied to Shakespeare the materials of his own comedy.

On this subject Malone thus writes. “The circumstance on which the Induction to the anonymous play, as well as to the present Comedy [Shakespeare’s “Taming of the Shrew”], is founded, is related (as Langbaine has observed) by Heuterus, “Rerum Burgund.” lib. iv. The earliest English original of this story in prose that I have met with is the following, which is found in Goulart’s “Admirable and Memorable Histories”, translated by E. Grimstone, quarto, 1607; but this tale (which Goulart translated from Heuterus) had undoubtedly appeared in English, in some other shape, before 1594:

“Philip called the good Duke of Burgundy, in the memory of our ancestors, being at Bruxelles with his Court, and walking one night after supper through the streets, accompanied by some of his favourites, he found lying upon the stones a certaine artisan that was very dronke, and that slept soundly. It pleased the prince in this artisan to make trial of the vanity of our life, whereof he had before discoursed with his familiar friends. He therefore caused this sleeper to be taken up, and carried into his palace; he commands him to be layed in one of the richest beds; a riche night cap to be given him; his foule shirt to be taken off, and to have another put on him of fine holland. When as this dronkard had digested his wine, and began to awake, behold there comes about his bed Pages and Groomes of the Duke’s Chamber, who drawe the curteines, make many courtesies, and being bare-headed, aske him if it please him to rise, and what apparell it would please him to put on that day. They bring him rich apparell. This new Monsieur amazed at such courtesie, and doubting whether he dreamt or waked, suffered himselfe to be drest, and led out of the chamber. There came noblemen which saluted him with all honour, and conduct him to the Masse, where with great ceremonie they give him the booke of the Gospell, and the Pixe to kisse, as they did usually to the Duke. From the Masse they bring him back unto the pallace; he washes his hands, and sittes down at the table well furnished. After dinner, the Great Chamberlain commands cards to be brought with a great summe of money. This Duke in imagination playes with the chief of the Court. Then they carry him to walke in the gardein, and to hunt the hare, and to hawke. They bring him back into the pallace, where he sups in state. Candles being light the musitions begin to play; and the tables taken away, the gentlemen and gentlewomen fell to dancing. Then they played a pleasant comedie, after which followed a Banket, whereat they had presently store of Ipocras and pretious wine, with all sorts of confitures, to this prince of the new impression; so as he was dronke, and fell soundlie asleepe. Hereupon the Duke commanded that he should be disrobed of all his riche attire. He was put into his old ragges, and carried into the same place, where he had been found the night before; where he spent that night. Being awake in the morning, he began to remember what had happened before; he knewe not whether it were true indeede, or a dream that had troubled his braine. But in the end, after many discourses, he concludes that ALL WAS BUT A DREAME that had happened unto him; and so entertained his wife, his children, and his neighbours, without any other apprehension.”

It is curious to find that the same anecdote which formed the Induction to the original “Taming of a Shrew”, and which, from a comic point of view, Shakespeare so wonderfully developed in his own comedy, Calderon invested with such solemn and sublime dignity in “La Vida es Sueno”. He found it, as Senor Hartzenbusch points out in the edition of 1872 already quoted, in the very amusing “Viage Entretenido” of Augustin de Rojas, which was first published in 1603. Hartzenbusch refers to the modern edition of Rojas, Madrid, 1793, tomo I, pp. 261, 262, 263, but in a copy of the Lerida edition of 1615, in my own possession, I find the anecdote at folios 118, 119, 120. There are some slight differences between the version of Rojas and that of Goulart, but the incidents and the persons are the same. The conclusion to which the artizan arrived at, in the version of Goulart, that all had been a dream, is expressed more strongly by the Duke himself in the story as told by Rojas.

“Y dijo entonces el Duque: ‘veis aqui, amigos, “Lo que es el Mundo: Todo es un Sueno”, pues esto verdaderamente ha pasado por este, como habeis visto, y le parece que lo ha sonado.'” —

The story in all probability came originally from the East. Mr. Lane in his translation of the Thousand and One Nights gives a very interesting narrative which he believes to be founded on an historical fact in which Haroun Al Raschid plays the part of the good Duke of Burgundy, and Abu-l-Hasan the original of Christopher Sly. The gravity of the treatment and certain incidents in this Oriental story recall more strongly Calderon’s drama than the Induction to the “Taming of the Shrew”. “La Vida es Sueno” was first published either at the end of 1635 or beginning of 1636.

The “Aprobacion” for its publication along with eleven other dramas (not nine as Archbishop Trench has stated), was signed on the 6th of November in the former year by the official licenser, Juan Bautista de Sossa. The volume was edited by the poet’s brother, Don Joseph Calderon. So scarce has this first authorised collection of any of Calderon’s dramas become, that a Spanish writer Don Vicente Garcia de la Huerta, in his “Teatro Espanol” (Parte Segunda, tomo 3o), denies the existence of this volume of 1635, and states that it did not appear until 1640. As if to corroborate this view, Barrera in his “Catalogo del Teatro antiguo Espanol” gives the date 1640 to the “Primera parte de comedias de Calderon” edited by his brother Joseph.

There can be no doubt, however, that the volume appeared in 1635 or 1636 as stated. In 1637 Don Joseph Calderon published the “Second Part” of his brother’s dramas containing like the former volume twelve plays.* In his dedication of this volume to D. Rodrigo de Mendoza, Joseph Calderon expressly alludes to the First Part of his brother’s comedies which he had “printed.” “En la primera Parte, Excellentissimo Senor, de las comedias que imprimi de Don Pedro Calderon de La Barca, mi hermano,” etc. This of course settles the fact of the prior publication of the first Part. It is singular, however, to find that the most famous of all Calderon’s dramas should have been frequently ascribed to Lope de Vega. So late as 1857 it is given in an Italian version by Giovanni La Cecilia, under the title of “La Vita e un Sogno”, as a drama of Lope de Vega, with the date 1628. This of course is a mistake, but Senor Hartzenbusch, who makes no allusion to this circumstance, admits that two dramas of Lope de Vega, which it is presumed preceded the composition of Calderon’s play turn on very nearly the same incidents as those of “La Vida es Sueno”. These are “Lo que ha de ser”, and “Barlan y Josafa”. He gives a passage from each of these dramas which seem to be the germ of the fine lament of Sigismund, which the reader will find translated in the present volume.

*In the library of the British Museum there is a fine copy of this "Segunda Parte de Comedias de Don Pedro Calderon de la Barca" Madrid, 1637. Mr. Ticknor mentions (1863) that he too had a copy of this interesting volume.

Senor Hartzenbusch, in the edition of Calderon's "La Vida es Sueno", already referred to (Madrid, 1872), prints the passages from Lope de Vega's two dramas, but in neither of them, he justly remarks, can we find anything that at all corresponds to this "grandioso caracter de Segismundo."

The second drama in this volume, "The Wonderful Magician", is perhaps better known to poetical students in England than even the first, from the spirited fragment Shelley has left us in his "Scenes from Calderon." The preoccupation of a subject by a great master throws immense difficulties in the way of any one who ventures to follow in the same path: but as Shelley allowed himself great licence in his versification, and either from carelessness or an imperfect knowledge of Spanish is occasionally unfaithful to the meaning of his author, it may be hoped in my own version that strict fidelity both as to the form as well as substance of the original may be some compensation for the absence of those higher poetical harmonies to which many of my readers will have been accustomed.

"El Magico Prodigioso" appeared for the first time in the same volume as "La Vida es Sueno", prepared for publication in 1635 by Don Joseph Calderon. The translation is comprised in the same number of lines as the original, and all the preceding remarks on "Life is a Dream", whether in reference to the period of the first publication of the drama in Spain, or the principles I kept in view while attempting this version may be applied to it. As in the Case of "Life is a Dream", "The Wonderful Magician" has previously been translated entire by an English writer, ("Justina", by J.H. 1848); but as Archbishop Trench truly observes, "the writer did not possess that command of the resources of the English language, which none more than Calderon requires."

The Legend on which Calderon founded "El Magico Prodigioso" will be found in Surius, "De probatis Sanctorum historiis", t. V. (Col. Agr. 1574), p. 351: "Vita et Martyrium SS. Cypriani et Justinae, autore Simeone Metaphraste", and in Chapter cxlii, of the "Legenda Aurea" of Jacobus de Voragine "De Sancta Justina virgine".

The martyrdom of the Saints took place in the year 290, and their festival is celebrated by the Church on the 26th of September.

Mr. Ticknor in his History of Spanish Literature, 1863, volume ii. p. 369, says that the Wonder-working Magician is founded on "the same legend on which Milman has founded his 'Martyr of Antioch.'" This is a mistake of the learned writer. "The Martyr of Antioch" is founded not on the history of St. Justina but of Saint Margaret, as Milman himself expressly states. Chapter xciii., "De Sancta Margareta", in the "Legenda Aurea" of Jacobus de Voragine contains her story.

The third translation in this volume is that of "The Purgatory of St. Patrick". This, though perhaps not so famous as the two preceding dramas, is intended to be given by Don P. De la Escosura, in a selection of Calderon's finest "comedias", now being edited by him for the Spanish Academy, as the representative piece of its class — namely, the mystical drama founded on the lives of Saints. Mr. Ticknor prefers it to the more celebrated "Devotion of the Cross," and says that it "is commonly ranked among the best religious plays of the Spanish theatre in the seventeenth century."

In all that relates to the famous cave known through the middle ages as the "Purgatory of Saint Patrick", as well as the Story of Luis Enius — the Owain Miles of Ancient English poetry — Calderon was entirely indebted to the little volume published at Madrid, in 1627, by Juan Perez de Montalvan, entitled "Vida y Purgatorio de San Patricio". This singular work met with immense success. It went through innumerable editions, and continues to be reprinted in Spain as a chap-book, down to the present day. I have the fifth impression "improved and enlarged by the author himself," Madrid, 1628, the year after its first appearance: also a later edition, Madrid, 1664. As early as 1637 a French translation appeared at Brussels by "F. A. S. Chartreux, a Bruxelles." In 1642 a second French translation was published at Troyes, by "R. P. Francois Bouillon, de l'Ordre de S. Francois, et Bachelier de Theologie." Mr. Thomas Wright in his "Essay on St. Patrick's Purgatory," London, 1844, makes the singular mistake of supposing that Bouillon's "Histoire de la Vie et Purgatoire de S. Patrice" was founded on the drama of Calderon, it being simply a translation of Montalvan's "Vida y Purgatorio," from which, like itself, Calderon's play was derived. Among other translations of Montalvan's work may be mentioned one in Dutch (Brussels, 1668) and one in Portuguese (Lisbon, 1738). It was also translated into German and Italian, but I find no mention of an English version. For this reason I have thought that a few extracts might be interesting, as showing how closely Calderon adhered even to the language of his predecessor.

In all that relates to the Purgatory, Montalvan's work is itself chiefly compiled from the "Florilegium Insulae Sanctorum, seu vitae et Actae sanctorum Hiberniae," Paris, 1624, fol. This work, which has now become scarce, was written by Thomas Messingham an Irish priest, the Superior of the Irish Seminary in Paris. No complete English version appears to have been made of it, but a small tract in English containing everything in the original work that referred to St. Patrick's Purgatory was published at Paris in 1718. As this tract is perhaps more scarce than even the Florilegium itself, the account of the Purgatory as given by Messingham from the MS. of Henry of Saltrey is reprinted in the notes to this drama in the quaint language of the anonymous translator. Of this tract, "printed at Paris in 1718" without the name of author, publisher or printer, I have not been able to trace another copy. In other points of interest connected with Calderon's drama, particularly to the clearing up of the difficulty hitherto felt as to the confused list of authorities at the end, the reader is also referred to the notes.

The present version of "The Purgatory of Saint Patrick" is, with the exception of a few unimportant lines, an entirely new translation. It is made with the utmost care, imitating all the measures and contained, like the two preceding dramas, in the exact number of lines of the original. One passage of the translation which I published in 1853 is retained in the notes, as a tribute of respect to the memory of the late John Rutter Chorley, it having been mentioned with praise by that eminent Spanish scholar in an elaborate review of my earlier translations from Calderon, which appeared in the "Athenaeum", Nov. 19 and Nov. 26, 1853.

It only remains to add that the text I have followed is that of Hartzenbusch in his edition of Calderon's Comedias, Madrid, 1856 ("Biblioteca de Autores Espanoles"). His arrangement of the scenes has been followed throughout, thus enabling the reader in a moment to verify for himself the exactness of the translation by a reference to the original, a crucial test which I rather invite than decline.

CLAPHAM PARK, Easter, 1873.

Life is a Dream

TO: Don Juan Eugenio Hartzenbusch; poet, dramatist, novelist, and critic, the most illustrious of living Spanish writers, this translation into English imitative verse of Calderon's most famous drama, is inscribed, with the esteem and regard of the author.

Characters:

BASILIUS, King of Poland.

SIGISMUND, his Son.

ASTOLFO, Duke of Muscovy.

CLOTALDO, a Nobleman.

ESTRELLA, a Princess.

ROSAURA, a Lady.

CLARIN, her Servant.

Soldiers.

Guards.

Musicians.

Attendants.

Ladies.

Servants.

The Scene is in the Court of Poland, in a fortress at some distance, and in the open field.

Life is a Dream

ACT THE FIRST

At one side a craggy mountain, at the other a tower, the lower part of which serves as the prison of Sigismund. The door facing the spectators is half open. The action commences at nightfall.

SCENE I.

ROSAURA in man's attire appears on the rocky heights and descends to the plain. She is followed by CLARIN.

ROSAURA: Wild hippogriff swift speeding,

Thou that dost run, the winged winds exceeding,

Bolt which no flash illumes,

Fish without scales, bird without shifting plumes,

And brute awhile bereft

Of natural instinct, why to this wild cleft,

This labyrinth of naked rocks, dost sweep

Unreined, uncurbed, to plunge thee down the steep?

Stay in this mountain wold,

And let the beasts their Phaeton behold.

For I, without a guide,

Save what the laws of destiny decide,

Benighted, desperate, blind.

Take any path whatever that doth wind

Down this rough mountain to its base,

Whose wrinkled brow in heaven frowns in the sun's bright face.

Ah, Poland! in ill mood

Hast thou received a stranger, since in blood

The name thou writest on thy sands

Of her who hardly here fares hardly at thy hands.

My fate may well say so:—

But where shall one poor wretch find pity in her woe?

CLARIN: Say two, if you please;

Don't leave me out when making plaints like these.

For if we are the two

Who left our native country with the view

Of seeking strange adventures, if we be

The two who, madly and in misery,

Have got so far as this, and if we still

Are the same two who tumbled down this hill,

Does it not plainly to a wrong amount,

To put me in the pain and not in the account?

ROSAURA: I do not wish to impart,

Clarin, to thee, the sorrows of my heart;

Mourning for thee would spoil the consolation

Of making for thyself thy lamentation;

For there is such a pleasure in complaining,

That a philosopher I've heard maintaining

One ought to seek a sorrow and be vain of it,

In order to be privileged to complain of it.

CLARIN: That same philosopher

Was an old drunken fool, unless I err:

Oh, that I could a thousand thumps present him,

In order for complaining to content him!

But what, my lady, say,

Are we to do, on foot, alone, our way

Lost in the shades of night?

For see, the sun descends another sphere to light.

ROSAURA: So strange a misadventure who has seen?

But if my sight deceives me not, between

These rugged rocks, half-lit by the moon's ray

And the declining day,

It seems, or is it fancy? that I see

A human dwelling?

CLARIN: So it seems to me,

Unless my wish the longed-for lodging mocks.

ROSAURA: A rustic little palace 'mid the rocks

Uplifts its lowly roof,

Scarce seen by the far sun that shines aloof.

Of such a rude device

Is the whole structure of this edifice,

That lying at the feet

Of these gigantic crags that rise to greet

The sun's first beams of gold,

It seems a rock that down the mountain rolled.

CLARIN: Let us approach more near,

For long enough we've looked at it from here;

Then better we shall see

If those who dwell therein will generously

A welcome give us.

ROSAURA: See an open door

(Funereal mouth 'twere best the name it bore),

From which as from a womb

The night is born, engendered in its gloom.

[The sound of chains is heard within.]

CLARIN: Heavens! what is this I hear?

ROSAURA: Half ice, half fire, I stand transfixed with fear.

CLARIN: A sound of chains, is it not?

Some galley-slave his sentence here hath got;

My fear may well suggest it so may be.

SCENE II.

SIGISMUND [in the tower.] ROSAURA, CLARIN.

SIGISMUND [within]: Alas! Ah, wretched me! Ah, wretched me!

ROSAURA: Oh what a mournful wail!

Again my pains, again my fears prevail.

CLARIN: Again with fear I die.

ROSAURA: Clarin!

CLARIN: My lady!

ROSAURA: Let us turn and fly

The risks of this enchanted tower.

CLARIN: For one,

I scarce have strength to stand, much less to run.

ROSAURA: Is not that glimmer there afar —

That dying exhalation — that pale star —

A tiny taper, which, with trembling blaze

Flickering 'twixt struggling flames and dying rays,

With ineffectual spark

Makes the dark dwelling place appear more dark?

Yes, for its distant light,

Reflected dimly, brings before my sight

A dungeon's awful gloom,

Say rather of a living corse, a living tomb;

And to increase my terror and surprise,

Drest in the skins of beasts a man there lies:

A piteous sight,

Chained, and his sole companion this poor light.

Since then we cannot fly,

Let us attentive to his words draw nigh,

Whatever they may be.

[The doors of the tower open wide, and SIGISMUND is discovered in chains and clad in the skins of beasts. The light in the tower increases.]

SIGISMUND: Alas! Ah, wretched me! Ah, wretched me!

Heaven, here lying all forlorn,

I desire from thee to know,

Since thou thus dost treat me so,

Why have I provoked thy scorn

By the crime of being born?—

Though for being born I feel

Heaven with me must harshly deal,

Since man's greatest crime on earth

Is the fatal fact of birth —

Sin supreme without appeal.

This alone I ponder o'er,

My strange mystery to pierce through;

Leaving wholly out of view

Germs my hapless birthday bore,

How have I offended more,

That the more you punish me?

Must not other creatures be

Born? If born, what privilege

Can they over me allege

Of which I should not be free?

Birds are born, the bird that sings,

Richly robed by Nature's dower,

Scarcely floats — a feathered flower,

Or a bunch of blooms with wings —

When to heaven's high halls it springs,

Cuts the blue air fast and free,

And no longer bound will be

By the nest's secure control:—

And with so much more of soul,

Must I have less liberty?

Beasts are born, the beast whose skin

Dappled o'er with beauteous spots,

As when the great pencil dots

Heaven with stars, doth scarce begin

From its impulses within—

Nature's stern necessity,

To be schooled in cruelty,—

Monster, waging ruthless war:—

And with instincts better far

Must I have less liberty?

Fish are born, the spawn that breeds

Where the oozy sea-weeds float,

Scarce perceives itself a boat,

Scaled and plated for its needs,

When from wave to wave it speeds,

Measuring all the mighty sea,

Testing its profundity

To its depths so dark and chill:—

And with so much freer will,

Must I have less liberty?

Streams are born, a coiled-up snake

When its path the streamlet finds,

Scarce a silver serpent winds

'Mong the flowers it must forsake,

But a song of praise doth wake,

Mournful though its music be,

To the plain that courteously

Opes a path through which it flies:—

And with life that never dies,

Must I have less liberty?

When I think of this I start,

Aetna-like in wild unrest

I would pluck from out my breast

Bit by bit my burning heart:—

For what law can so depart

From all right, as to deny

One lone man that liberty —

That sweet gift which God bestows

On the crystal stream that flows,

Birds and fish that float or fly?

ROSAURA: Fear and deepest sympathy

Do I feel at every word.

SIGISMUND: Who my sad lament has heard?

What! Clotaldo!

CLARIN [aside to his mistress]: Say 'tis he.

ROSAURA: No, 'tis but a wretch (ah, me!)

Who in these dark caves and cold

Hears the tale your lips unfold.

SIGISMUND: Then you'll die for listening so,

That you may not know I know

That you know the tale I told.

[Seizes her.]

Yes, you'll die for loitering near:

In these strong arms gaunt and grim

I will tear you limb from limb.

CLARIN: I am deaf and couldn't hear:—No!

ROSAURA: If human heart you bear,

'Tis enough that I prostrate me.

At thy feet, to liberate me!

SIGISMUND: Strange thy voice can so unbend me,

Strange thy sight can so suspend me,

And respect so penetrate me!

Who art thou? for though I see

Little from this lonely room,

This, my cradle and my tomb.

Being all the world to me,

And if birthday it could be,

Since my birthday I have known

But this desert wild and lone,

Where throughout my life's sad course

I have lived, a breathing corse,

I have moved, a skeleton;

And though I address or see

Never but one man alone,

Who my sorrows all hath known,

And through whom have come to me

Notions of earth, sky, and sea;

And though harrowing thee again,

Since thou'lt call me in this den,

Monster fit for bestial feasts,

I'm a man among wild beasts,

And a wild beast amongst men.

But though round me has been wrought

All this woe, from beasts I've learned

Polity, the same discerned

Heeding what the birds had taught,

And have measured in my thought

The fair orbits of the spheres;

You alone, 'midst doubts and fears,

Wake my wonder and surprise —

Give amazement to my eyes,

Admiration to my ears.

Every time your face I see

You produce a new amaze:

After the most steadfast gaze,

I again would gazer be.

I believe some hydropsy

Must affect my sight, I think

Death must hover on the brink

Of those wells of light, your eyes,

For I look with fresh surprise,

And though death result, I drink.

Let me see and die: forgive me;

For I do not know, in faith,

If to see you gives me death,

What to see you not would give me;

Something worse than death would grieve me,

Anger, rage, corroding care,

Death, but double death it were,

Death with tenfold terrors rife,

Since what gives the wretched life,

Gives the happy death, despair!

ROSAURA: Thee to see wakes such dismay,

Thee to hear I so admire,

That I'm powerless to inquire,

That I know not what to say:

Only this, that I to-day,

Guided by a wiser will,

Have here come to cure my ill,

Here consoled my grief to see,

If a wretch consoled can be

Seeing one more wretched still.

Of a sage, who roamed dejected,

Poor, and wretched, it is said,

That one day, his wants being fed

By the herbs which he collected,

"Is there one" (he thus reflected)

"Poorer than I am to-day?"

Turning round him to survey,

He his answer got, detecting

A still poorer sage collecting

Even the leaves he threw away.

Thus complaining to excess,

Mourning fate, my life I led,

And when thoughtlessly I said

To myself, "Does earth possess

One more steeped in wretchedness?"

I in thee the answer find.

Since revolving in my mind,

I perceive that all my pains

To become thy joyful gains

Thou hast gathered and entwined.

And if haply some slight solace

By these pains may be imparted,*

Hear attentively the story

Of my life's supreme disasters.

I am ….

*The metre changes here to the vocal "asonante" in "a—e", and continues to the end of the Fourth Scene.

SCENE III.

CLOTALDO, Soldiers, SIGISMUND, ROSAURA, CLARIN.

CLOTALDO [within]: Warders of this tower,

Who, or sleeping or faint-hearted,

Give an entrance to two persons

Who herein have burst a passage . . . .

ROSAURA: New confusion now I suffer.

SIGISMUND: 'Tis Clotaldo, who here guards me;

Are not yet my miseries ended?

CLOTALDO [within]: Hasten hither, quick! be active!

And before they can defend them,

Kill them on the spot, or capture!

[Voices within.] Treason!

CLARIN: Watchguards of this tower,

Who politely let us pass here,

Since you have the choice of killing

Or of capturing, choose the latter.

[Enter CLOTALDO and Soldiers; he with a pistol, and all with their faces covered.]

CLOTALDO [aside to the Soldiers]: Keep your faces all well covered,

For it is a vital matter

That we should be known by no one,

While I question these two stragglers.

CLARIN: Are there masqueraders here?

CLOTALDO: Ye who in your ignorant rashness

Have passed through the bounds and limits

Of this interdicted valley,

'Gainst the edict of the King,

Who has publicly commanded

None should dare descry the wonder

That among these rocks is guarded,

Yield at once your arms and lives,

Or this pistol, this cold aspic

Formed of steel, the penetrating

Poison of two balls will scatter,

The report and fire of which

Will the air astound and startle.

SIGISMUND: Ere you wound them, ere you hurt them,

Will my life, O tyrant master,

Be the miserable victim

Of these wretched chains that clasp me;

Since in them, I vow to God,

I will tear myself to fragments

With my hands, and with my teeth,

In these rocks here, in these caverns,

Ere I yield to their misfortunes,

Or lament their sad disaster.

CLOTALDO: If you know that your misfortunes,

Sigismund, are unexampled,

Since before being born you died

By Heaven's mystical enactment;

If you know these fetters are

Of your furies oft so rampant

But the bridle that detains them,

But the circle that contracts them.

Why these idle boasts? The door

[To the Soldiers.]

Of this narrow prison fasten;

Leave him there secured.

SIGISMUND: Ah, heavens,

It is wise of you to snatch me

Thus from freedom! since my rage

'Gainst you had become Titanic,

Since to break the glass and crystal

Gold-gates of the sun, my anger

On the firm-fixed rocks' foundations

Would have mountains piled of marble.

CLOTALDO: 'Tis that you should not so pile them

That perhaps these ills have happened,

[Some of the SOLDIERS lead SIGISMUND into his prison, the doors of which are closed upon him.]

SCENE IV.

ROSAURA, CLOTALDO, CLARIN, Soldiers.

ROSAURA: Since I now have seen how pride

Can offend thee, I were hardened

Sure in folly not here humbly

At thy feet for life to ask thee;

Then to me extend thy pity,

Since it were a special harshness

If humility and pride,

Both alike were disregarded.

CLARIN: If Humility and Pride

Those two figures who have acted

Many and many a thousand times

In the "autos sacramentales",

Do not move you, I, who am neither

Proud nor humble, but a sandwich

Partly mixed of both, entreat you

To extend to us your pardon.

CLOTALDO: Ho!

SOLDIERS: My lord?

CLOTALDO: Disarm the two,

And their eyes securely bandage,

So that they may not be able

To see whither they are carried.

ROSAURA: This is, sir, my sword; to thee

Only would I wish to hand it,

Since in fine of all the others

Thou art chief, and I could hardly

Yield it unto one less noble.

CLARIN: Mine I'll give the greatest rascal

Of your troop: [To a Soldier.] so take it, you.

ROSAURA: And if I must die, to thank thee

For thy pity, I would leave thee

This as pledge, which has its value

From the owner who once wore it;

That thou guard it well, I charge thee,

For although I do not know

What strange secret it may carry,

This I know, that some great mystery

Lies within this golden scabbard,

Since relying but on it

I to Poland here have travelled

To revenge a wrong.

CLOTALDO [aside.]: Just heavens!

What is this? Still graver, darker,

Grow my doubts and my confusion,

My anxieties and my anguish.—

Speak, who gave you this?

ROSAURA: A woman.

CLOTALDO: And her name?

ROSAURA: To that my answer

Must be silence.

CLOTALDO: But from what

Do you now infer, or fancy,

That this sword involves a secret?

ROSAURA: She who gave it said: "Depart hence

Into Poland, and by study,

Stratagem, and skill so manage

That this sword may be inspected

By the nobles and the magnates

Of that land, for you, I know,

Will by one of them be guarded,"—

But his name, lest he was dead,

Was not then to me imparted.

CLOTALDO [aside]: Bless me, Heaven! what's this I hear?

For so strangely has this happened,

That I cannot yet determine

If 'tis real or imagined.

This is the same sword that I

Left with beauteous Violante,

As a pledge unto its wearer,

Who might seek me out thereafter,

As a son that I would love him,

And protect him as a father.

What is to be done (ah, me!)

In confusion so entangled,

If he who for safety bore it

Bears it now but to dispatch him,

Since condemned to death he cometh

To my feet? How strange a marvel!

What a lamentable fortune!

How unstable! how unhappy!

This must be my son — the tokens

All declare it, superadded

To the flutter of the heart,

That to see him loudly rappeth

At the breast, and not being able

With its throbs to burst its chamber,

Does as one in prison, who,

Hearing tumult in the alley,

Strives to look from out the window;

Thus, not knowing what here passes

Save the noise, the heart uprusheth

To the eyes the cause to examine —

They the windows of the heart,

Out through which in tears it glances.

What is to be done? (O Heavens!)

What is to be done? To drag him

Now before the King were death;

But to hide him from my master,

That I cannot do, according

To my duty as a vassal.

Thus my loyalty and self-love

Upon either side attack me;

Each would win. But wherefore doubt?

Is not loyalty a grander,

Nobler thing than life, than honour?

Then let loyalty live, no matter

That he die; besides, he told me,

If I well recall his language,

That he came to revenge a wrong,

But a wronged man is a lazar,—

No, he cannot be my son,

Not the son of noble fathers.

But if some great chance, which no one

Can be free from, should have happened,

Since the delicate sense of honour

Is a thing so fine, so fragile,

That the slightest touch may break it,

Or the faintest breath may tarnish,

What could he do more, do more,

He whose cheek the blue blood mantles,

But at many risks to have come here

It again to re-establish?

Yes, he is my son, my blood,

Since he shows himself so manly.

And thus then betwixt two doubts

A mid course alone is granted:

'Tis to seek the King, and tell him

Who he is, let what will happen.

A desire to save my honour

May appease my royal master;

Should he spare his life, I then

Will assist him in demanding

His revenge; but if the King

Should, persisting in his anger,

Give him death, then he will die

Without knowing I'm his father.—

[To ROSAURA and CLARIN.]

Come, then, come then with me, strangers.

Do not fear in your disasters

That you will not have companions

In misfortune; for so balanced

Are the gains of life or death,

That I know not which are larger.

[Exeunt.]

* * * * *

SCENE V.

A HALL IN THE ROYAL PALACE.

[Enter at one side ASTOLFO and Soldiers, and at the other the INFANTA

ESTRELLA and her Ladies. Military music and salutes within.]

ASTOLFO: Struck at once with admiration

At thy starry eyes outshining,

Mingle many a salutation,

Drums and trumpet-notes combining,

Founts and birds in alternation;

Wondering here to see thee pass,

Music in grand chorus gathers

All her notes from grove and grass:

Here are trumpets formed of feathers,

There are birds that breathe in brass.

All salute thee, fair Senora,

Ordnance as their Queen proclaim thee,

Beauteous birds as their Aurora,

As their Pallas trumpets name thee,

And the sweet flowers as their Flora;

For Aurora sure thou art,

Bright as day that conquers night —

Thine is Flora's peaceful part,

Thou art Pallas in thy might,

And as Queen thou rul'st my heart.

ESTRELLA: If the human voice obeying

Should with human action pair,

Then you have said ill in saying

All these flattering words and fair,

Since in truth they are gainsaying

This parade of victory,

'Gainst which I my standard rear,

Since they say, it seems to me,

Not the flatteries that I hear,

But the rigours that I see.

Think, too, what a base invention

From a wild beast's treachery sprung,—

Fraudful mother of dissension —

Is to flatter with the tongue,

And to kill with the intention.

ASTOLFO: Ill informed you must have been,

Fair Estrella, thus to throw

Doubt on my respectful mien:

Let your ear attentive lean

While the cause I strive show.

King Eustorgius the Fair,

Third so called, died leaving two

Daughters, and Basilius heir;

Of his sisters I and you

Are the children — I forbear

To recall a single scene

Save what's needful. Clorilene,

Your good mother and my aunt,

Who is now a habitant

Of a sphere of sunnier sheen,

Was the elder, of whom you

Are the daughter; Recisunda,

Whom God guard a thousand years,

Her fair sister (Rosamunda

Were she called if names were true)

Wed in Muscovy, of whom

I was born. 'Tis needful now

The commencement to resume.

King Basilius, who doth bow

'Neath the weight of years, the doom

Age imposes, more inclined

To the studies of the mind

Than to women, wifeless, lone,

Without sons, to fill his throne

I and you our way would find.

You, the elder's child, averred,

That the crown you stood more nigh:

I, maintaining that you erred,

Held, though born of the younger, I,

Being a man, should be preferred.

Thus our mutual pretension

To our uncle we related,

Who replied that he would mention

Here, and on this day he stated,

What might settle the dissension.

With this end, from Muscovy

I set out, and with that view,

I to-day fair Poland see,

And not making war on you,

Wait till war you make on me.

Would to love — that God so wise —

That the crowd may be a sure

Astrologue to read the skies,

And this festive truce secure

Both to you and me the prize,

Making you a Queen, but Queen

By my will, our uncle leaving

You the throne we'll share between —

And my love a realm receiving

Dearer than a King's demesne.

ESTRELLA. Well, I must be generous too,

For a gallantry so fine;

This imperial realm you view,

If I wish it to be mine

'Tis to give it unto you.

Though if I the truth confessed,

I must fear your love may fail —

Flattering words are words at best,

For perhaps a truer tale

Tells that portrait on your breast.

ASTOLFO. On that point complete content

Will I give your mind, not here,

For each sounding instrument

[Drums are heard.]

Tells us that the King is near,

With his Court and Parliament.

* * * * *

SCENE VI.

The KING BASILIUS, with his retinue. —

ASTOLFO, ESTRELLA, Ladies, Soldiers.

ESTRELLA: Learned Euclid . . .

ASTOLFO: Thales wise . .

ESTRELLA: The vast Zodiac . . .

ASTOLFO: The star spaces . . .

ESTRELLA: Who dost soar to . . .

ASTOLFO: Who dost rise…

ESTRELLA: The sun's orbit . . .

ASTOLFO: The stars' places . . .

ESTRELLA: To describe . . .

ASTOLFO: To map the skies . . .

ESTRELLA: Let me humbly interlacing . . .

ASTOLFO: Let me lovingly embracing . . .

ESTRELLA: Be the tendril of thy tree.

ASTOLFO: Bend respectfully my knee.

BASILIUS: Children, that dear word displacing

Colder names, my arms here bless;

And be sure, since you assented

To my plan, my love's excess

Will leave neither discontented,

Or give either more or less.

And though I from being old

Slowly may the facts unfold,

Hear in silence my narration,

Keep reserved your admiration,

Till the wondrous tale is told.

You already know — I pray you

Be attentive, dearest children,*

Great, illustrious Court of Poland,

Faithful vassals, friends and kinsmen,

You already know — my studies

Have throughout the whole world given me

The high title of "the learned,"

Since 'gainst time and time's oblivion

The rich pencils of Timanthes,

The bright marbles of Lysippus,

Universally proclaim me

Through earth's bounds the great Basilius.

You already know the sciences

That I feel my mind most given to

Are the subtle mathematics,

By whose means my clear prevision

Takes from rumour its slow office,

Takes from time its jurisdiction

Of, each day, new facts disclosing;

Since in algebraic symbols

When the fate of future ages

On my tablets I see written,

I anticipate time in telling

What my science hath predicted.

All those circles of pure snow,

All those canopies of crystal,

Which the sun with rays illumines,

Which the moon cuts in its circles,

All those orbs of twinkling diamond,

All those crystal globes that glisten,

All that azure field of stars

Where the zodiac signs are pictured,

Are the study of my life,

Are the books where heaven has written

Upon diamond-dotted paper,

Upon leaves by sapphires tinted,

With light luminous lines of gold,

In clear characters distinctly

All the events of human life,

Whether adverse or benignant.

These so rapidly I read

That I follow with the quickness

Of my thoughts the swiftest movements

Of their orbits and their circles.

Would to heaven, that ere my mind

To those mystic books addicted

Was the comment of their margins

And of all their leaves the index,

Would to heaven, I say, my life

Had been offered the first victim

Of its anger, that my death-stroke

Had in this way have been given me,

Since the unhappy find even merit

Is the fatal knife that kills them,

And his own self-murderer

Is the man whom knowledge injures!—

I may say so, but my story

So will say with more distinctness,

And to win your admiration

Once again I pray you listen.—

Clorilene, my wife, a son

Bore me, so by fate afflicted

That on his unhappy birthday

All Heaven's prodigies assisted.

Nay, ere yet to life's sweet life

Gave him forth her womb, that living

Sepulchre (for death and life

Have like ending and beginning),

Many a time his mother saw

In her dreams' delirious dimness

From her side a monster break,

Fashioned like a man, but sprinkled

With her blood, who gave her death,

By that human viper bitten.

Round his birthday came at last,

All its auguries fulfilling

(For the presages of evil

Seldom fail or even linger):

Came with such a horoscope,

That the sun rushed blood-red tinted

Into a terrific combat

With the dark moon that resisted;

Earth its mighty lists outspread

As with lessening lights diminished

Strove the twin-lamps of the sky.

'Twas of all the sun's eclipses

The most dreadful that it suffered

Since the hour its bloody visage

Wept the awful death of Christ.

For o'erwhelmed in glowing cinders

The great orb appeared to suffer

Nature's final paroxysm.

Gloom the glowing noontide darkened,

Earthquake shook the mightiest buildings,

Stones the angry clouds rained down,

And with blood ran red the rivers.

In this frenzy of the sun,

In its madness and delirium,

Sigismund was born, thus early

Giving proofs of his condition,

Since his birth his mother slew,

Just as if these words had killed her,

"I am a man, since good with evil

I repay here from the beginning,"—

I, applying to my studies,

Saw in them as 'twere forewritten

This, that Sigismund would be

The most cruel of all princes,

Of all men the most audacious,

Of all monarchs the most wicked;

That his kingdom through his means

Would be broken and partitioned,

The academy of the vices,

And the high school of sedition;

And that he himself, borne onward

By his crimes' wild course resistless,

Would even place his feet on me;

For I saw myself down-stricken,

Lying on the ground before him

(To say this what shame it gives me!)

While his feet on my white hairs

As a carpet were imprinted.

Who discredits threatened ill,

Specially an ill previsioned

By one's study, when self-love

Makes it his peculiar business?—

Thus then crediting the fates

Which far off my science witnessed,

All these fatal auguries

Seen though dimly in the distance,

I resolved to chain the monster

That unhappily life was given to,

To find out if yet the stars

Owned the wise man's weird dominion.

It was publicly proclaimed

That the sad ill-omened infant

Was stillborn. I then a tower

Caused by forethought to be builded

'Mid the rocks of these wild mountains

Where the sunlight scarce can gild it,

Its glad entrance being barred

By these rude shafts obeliscal.

All the laws of which you know,

All the edicts that prohibit

Anyone on pain of death

That secluded part to visit

Of the mountain, were occasioned

By this cause, so long well hidden.

There still lives Prince Sigismund,

Miserable, poor, in prison.

Him alone Clotaldo sees,

Only tends to and speaks with him;

He the sciences has taught him,

He the Catholic religion

Has imparted to him, being

Of his miseries the sole witness.

Here there are three things: the first

I rate highest, since my wishes

Are, O Poland, thee to save

From the oppression, the affliction

Of a tyrant King, because

Of his country and his kingdom

He were no benignant father

Who to such a risk could give it.

Secondly, the thought occurs

That to take from mine own issue

The plain right that every law

Human and divine hath given him

Is not Christian charity;

For by no law am I bidden

To prevent another proving,

Say, a tyrant, or a villain,

To be one myself: supposing

Even my son should be so guilty,

That he should not crimes commit

I myself should first commit them.

Then the third and last point is,

That perhaps I erred in giving

Too implicit a belief

To the facts foreseen so dimly;

For although his inclination

Well might find its precipices,

He might possibly escape them:

For the fate the most fastidious,

For the impulse the most powerful.

Even the planets most malicious

Only make free will incline,

But can force not human wishes.

And thus 'twist these different causes

Vacillating and unfixed,

I a remedy have thought of

Which will with new wonder fill you.

I to-morrow morning purpose,

Without letting it be hinted

That he is my son, and therefore

Your true King, at once to fix him

As King Sigismund (for the name

Still he bears that first was given him)

'Neath my canopy, on my throne,

And in fine in my position,

There to govern and command you,

Where in dutiful submission

You will swear to him allegiance.

My resources thus are triple,

As the causes of disquiet

Were which I revealed this instant.

The first is; that he being prudent,

Careful, cautious and benignant,

Falsifying the wild actions

That of him had been predicted,

You'll enjoy your natural prince,

He who has so long been living

Holding court amid these mountains,

With the wild beasts for his circle.

Then my next resource is this:

If he, daring, wild, and wicked,

Proudly runs with loosened rein

O'er the broad plain of the vicious,

I will have fulfilled the duty

Of my natural love and pity;

Then his righteous deposition

Will but prove my royal firmness,

Chastisement and not revenge

Leading him once more to the prison.

My third course is this: the Prince

Being what my words have pictured,

From the love I owe you, vassals,

I will give you other princes

Worthier of the crown and sceptre;

Namely, my two sisters' children,

Who their separate pretensions

Having happily commingled

By the holy bonds of marriage,

Will then fill their fit position.

This is what a king commands you,

This is what a father bids you,

This is what a sage entreats you,

This is what an old man wishes;

And as Seneca, the Spaniard,

Says, a king for all his riches

Is but slave of his Republic,

This is what a slave petitions.

*The metre changes here to the "asonante" in "i—e", or their vocal equivalents, and is kept up for the remainder of the Act.

ASTOLFO: If on me devolves the answer,

As being in this weighty business

The most interested party,

I, of all, express the opinion:—

Let Prince Sigismund appear;

He's thy son, that's all-sufficient.

ALL. Give to us our natural prince,

We proclaim him king this instant!

BASILIUS: Vassals, from my heart I thank you

For this deference to my wishes:—

Go, conduct to their apartments

These two columns of my kingdom,

On to-morrow you shall see him.

ALL. Live, long live great King Basilius!

[Exeunt all, accompanying ESTRELLA and ASTOLFO;

The King remains.]

SCENE VII.

CLOTALDO, ROSAURA, CLARIN, and BASILIUS.

CLOTALDO: May I speak to you, sire?

BASILIUS: Clotaldo,

You are always welcome with me.

CLOTALDO: Although coming to your feet

Shows how freely I'm admitted,

Still, your majesty, this once,

Fate as mournful as malicious

Takes from privilege its due right,

And from custom its permission.

BASILIUS: What has happened?

CLOTALDO: A misfortune,

Sire, which has my heart afflicted

At the moment when all joy

Should have overflown and filled it.

BASILIUS: Pray proceed.

CLOTALDO: This handsome youth here,

Inadvertently, or driven

By his daring, pierced the tower,

And the Prince discovered in it.

Nay . . . .

BASILIUS: Clotaldo, be not troubled

At this act, which if committed

At another time had grieved me,

But the secret so long hidden

Having myself told, his knowledge

Of the fact but matters little.

See me presently, for I

Much must speak upon this business,

And for me you much must do

For a part will be committed

To you in the strangest drama

That perhaps the world e'er witnessed.

As for these, that you may know

That I mean not your remissness

To chastise, I grant their pardon.

[Exit.]

CLOTALDO: Myriad years to my lord be given!

SCENE VIII.

CLOTALDO, ROSAURA, and CLARIN.

CLOTALDO [aside]: Heaven has sent a happier fate;

Since I need not now admit it,

I'll not say he is my son.—

Strangers who have wandered hither,

You are free.

ROSAURA: I give your feet

A thousand kisses.

CLARIN: I say misses,

For a letter more or less

'Twixt two friends is not considered.

ROSAURA: You have given me life, my lord,

And since by your act I'm living,

I eternally will own me

As your slave.

CLOTALDO: The life I've given

Is not really your true life,

For a man by birth uplifted

If he suffers an affront

Actually no longer liveth;

And supposing you have come here

For revenge as you have hinted,

I have not then given you life,

Since you have not brought it with you,

For no life disgraced is life.—

[Aside.] (This I say to arouse his spirit.)

ROSAURA: I confess I have it not,

Though by you it has been given me;

But revenge being wreaked, my honour

I will leave so pure and limpid,

All its perils overcome,

That my life may then with fitness

Seem to be a gift of yours.

CLOTALDO: Take this burnished sword which hither

You brought with you; for I know,

To revenge you, 'tis sufficient,

In your enemy's blood bathed red;

For a sword that once was girded

Round me (I say this the while

That to me it was committed),

Will know how to right you.

ROSAURA: Thus

In your name once more I gird it,

And on it my vengeance swear,

Though the enemy who afflicts me

Were more powerful.

CLOTALDO: Is he so?

ROSAURA: Yes; so powerful, I am hindered

Saying who he is, not doubting

Even for greater things your wisdom

And calm prudence, but through fear

Lest against me your prized pity

Might be turned.

CLOTALDO: 'Twill rather be,

By declaring it, more kindled;

Otherwise you bar the passage

'Gainst your foe of my assistance.—

[Aside.] (Would that I but knew his name!)

ROSAURA: Not to think I set so little

Value on such confidence,

Know my enemy and my victim

Is no less than Prince Astolfo,

Duke of Muscovy.

CLOTALDO [aside]: Resistance

Badly can my grief supply

Since 'tis heavier than I figured.

Let us sift the matter deeper.—

If a Muscovite by birth, then

He who is your natural lord

Could not 'gainst you have committed

Any wrong; reseek your country,

And abandon the wild impulse

That has driven you here.

ROSAURA: I know,

Though a prince, he has committed

'Gainst me a great wrong.

CLOTALDO: He could not,

Even although your face was stricken

By his angry hand. [Aside.] (Oh, heavens!)

ROSAURA: Mine's a wrong more deep and bitter.

CLOTALDO: Tell it, then; it cannot be

Worse than what my fancy pictures.

ROSAURA: I will tell it; though I know not,

With the respect your presence gives me,

With the affection you awaken,

With the esteem your worth elicits,

How with bold face here to tell you

That this outer dress is simply

An enigma, since it is not

What it seems. And from this hint, then,

If I'm not what I appear,

And Astolfo with this princess

Comes to wed, judge how by him

I was wronged: I've said sufficient.

[Exeunt ROSAURA and CLARIN.]

CLOTALDO: Listen! hear me! wait! oh, stay!

What a labyrinthine thicket

Is all this, where reason gives

Not a thread whereby to issue?

My own honour here is wronged,

Powerful is my foe's position,

I a vassal, she a woman;

Heaven reveal some way in pity,

Though I doubt it has the power;

When in such confused abysses,

Heaven is all one fearful presage,

And the world itself a riddle.

ACT THE SECOND.

A HALL IN THE ROYAL PALACE.

SCENE I.

BASILIUS and CLOTALDO.

CLOTALDO: Everything has been effected

As you ordered.

BASILIUS: How all happened*

Let me know, my good Clotaldo.

*The metre of this and the following scene is the asonante in a—e.

CLOTALDO: It was done, sire, in this manner.

With the tranquillising draught,

Which was made, as you commanded,

Of confections duly mixed

With some herbs, whose juice extracted

Has a strange tyrannic power,

Has some secret force imparted,

Which all human sense and speech

Robs, deprives, and counteracteth,

And as 'twere a living corpse

leaves the man whose lips have quaffed it

So asleep that all his senses,

All his powers are overmastered . . . .

— No need have we to discuss

That this fact can really happen,

Since, my lord, experience gives us

Many a clear and proved example;

Certain 'tis that Nature's secrets

May by medicine be extracted,

And that not an animal,

Not a stone, or herb that's planted,

But some special quality

Doth possess: for if the malice

Of man's heart, a thousand poisons

That give death, hath power to examine,

Is it then so great a wonder

That, their venom being abstracted,

If, as death by some is given,

Sleep by others is imparted?

Putting, then, aside the doubt

That 'tis possible this should happen,

A thing proved beyond all question

Both by reason and example . . . .

— With the sleeping draught, in fine,

Made of opium superadded

To the poppy and the henbane,

I to Sigismund's apartment —

Cell, in fact — went down, and with him

Spoke awhile upon the grammar

Of the sciences, those first studies

Which mute Nature's gentle masters,

Silent skies and hills, had taught him;

In which school divine and ample,

The bird's song, the wild beast's roar,

Were a lesson and a language.

Then to raise his spirit more

To the high design you planned here,

I discoursed on, as my theme,

The swift flight, the stare undazzled

Of a pride-plumed eagle bold,

Which with back-averted talons,

Scorning the tame fields of air,

Seeks the sphere of fire, and passes

Through its flame a flash of feathers,

Or a comet's hair untangled.

I extolled its soaring flight,

Saying, "Thou at last art master

Of thy house, thou'rt king of birds,

It is right thou should'st surpass them."

He who needed nothing more

Than to touch upon the matter

Of high royalty, with a bearing

As became him, boldly answered;

For in truth his princely blood

Moves, excites, inflames his ardour

To attempt great things: he said,

"In the restless realm of atoms

Given to birds, that even one

Should swear fealty as a vassal!

I, reflecting upon this,

Am consoled by my disasters,

For, at least, if I obey,

I obey through force: untrammelled,

Free to act, I ne'er will own

Any man on earth my master."—

This, his usual theme of grief,

Having roused him nigh to madness,

I occasion took to proffer

The drugged draught: he drank, but hardly

Had the liquor from the vessel

Passed into his breast, when fastest

Sleep his senses seized, a sweat,

Cold as ice, the life-blood hardened

In his veins, his limbs grew stiff,

So that, knew I not 'twas acted,

Death was there, feigned death, his life

I could doubt not had departed.

Then those, to whose care you trust

This experiment, in a carriage

Brought him here, where all things fitting

The high majesty and the grandeur

Of his person are provided.

In the bed of your state chamber

They have placed him, where the stupor

Having spent its force and vanished,

They, as 'twere yourself, my lord,

Him will serve as you commanded:

And if my obedient service

Seems to merit some slight largess,

I would ask but this alone

(My presumption you will pardon),

That you tell me, with what object

Have you, in this secret manner,

To your palace brought him here?

BASILIUS. Good Clotaldo, what you ask me

Is so just, to you alone

I would give full satisfaction.

Sigismund, my son, the hard

Influence of his hostile planet

(As you know) doth threat a thousand

Dreadful tragedies and disasters;

I desire to test if Heaven

(An impossible thing to happen)

Could have lied — if having given us

Proofs unnumbered, countless samples

Of his evil disposition,

He might prove more mild, more guarded

At the lest, and self-subdued

By his prudence and true valour

Change his character; for 'tis man

That alone controls the planets.

This it is I wish to test,

Having brought him to this palace,

Where he'll learn he is my son,

And display his natural talents.

If he nobly hath subdued him,

He will reign; but if his manners

Show him tyrannous and cruel,

Then his chains once more shall clasp him.

But for this experiment,

Now you probably will ask me

Of what moment was't to bring him

Thus asleep and in this manner?

And I wish to satisfy you,

Giving all your doubts an answer.

If to-day he learns that he

Is my son, and some hours after

Finds himself once more restored

To his misery and his shackles,

Certain 'tis that from his temper

Blank despair may end in madness —

But once knowing who he is,

Can he be consoled thereafter?

Yes, and thus I wish to leave

One door open, one free passage,

By declaring all he saw

Was a dream. With this advantage

We attain two ends. The first

Is to put beyond all cavil

His condition, for on waking

He will show his thoughts, his fancies:

To console him is the second;

Since, although obeyed and flattered,

He beholds himself awhile,

And then back in prison shackled

Finds him, he will think he dreamed.

And he rightly so may fancy,

For, Clotaldo, in this world

All who live but dream they act here.

CLOTALDO: Reasons fail me not to show

That the experiment may not answer;

But there is no remedy now,

For a sign from the apartment

Tells me that he hath awoken

And even hitherward advances.

BASILIUS: It is best that I retire;

But do you, so long his master,

Near him stand; the wild confusion

That his waking sense may darken

Dissipate by simple truth.

CLOTALDO: Then your licence you have granted

That I may declare it?

BASILIUS: Yes;

For it possibly may happen

That admonished of his danger

He may conquer his worst passions.

[Exit]

SCENE II.

CLARIN and CLOTALDO.

CLARIN [aside]: Four good blows are all it cost me

To come here, inflicted smartly

By a red-robed halberdier,

With a beard to match his jacket,

At that price I see the show,

For no window's half so handy

As that which, without entreating

Tickets of the ticket-master,

A man carried with himself;

Since for all the feasts and galas

Cool effrontery is the window

Whence at ease he gazes at them.

CLOTALDO [aside]: This is Clarin, heavens! of her,

Yes, I say, of her the valet,

She, who dealing in misfortunes,

Has my pain to Poland carried:—

Any news, friend Clarin?

CLARIN: News?

Yes, sir, since your great compassion

Is disposed Rosaura's outrage

To revenge, she has changed her habit,

And resumed her proper dress.

CLOTALDO: 'Tis quite right, lest possible scandal

Might arise.

CLARIN: More news: her name

Having changed and wisely bartered

For your niece's name, she now

So in honour has advanced her,

That among Estrella's ladies

She here with her in the palace

Lives.

CLOTALDO: 'Tis right that I once more

Should her honour re-establish.

CLARIN: News; that anxiously she waiteth

For that very thing to happen,

When you may have time to try it.

CLOTALDO: Most discreetly has she acted;

Soon the time will come, believe me,

Happily to end this matter.

CLARIN: News, too; that she's well regaled,

Feasted like a queen, and flattered

On the strength of being your niece.

And the last news, and the saddest,

Is that I who here came with her

Am with hunger almost famished.

None remember me, or think

I am Clarin, clarion rather,

And that if that clarion sounded,

All the Court would know what passes.

For there are two things, to wit,

A brass clarion and a lackey,

That are bad at keeping secrets;

And it so may chance, if haply

I am forced to break my silence,

They of me may sing this passage:

"Never, when the day is near,

Does clarion sound more clear."*

* *"Clarin, que rompe el albor, No suena mejor."— This is a quotation by Calderon from his own drama, "En esta vida todo es verdad y todo mentira." — Act 2, sc. x.

CLOTALDO. Your complaint is too well-founded;

I will get you satisfaction,

Meanwhile you may wait on me.

CLARIN. See, sir, Sigismund advances.

SCENE III.

[Music and song.] SIGISMUND enters, lost in amazement. Servants minister to him, presenting costly robes. —CLOTALDO, and CLARIN.

SIGISMUND: Help me, Heaven, what's this I see!

Help me, Heaven, what's this I view!

Things I scarce believe are true,

But, if true, which fright not me.

I in palaces of state?

I 'neath silks and cloth of gold?

I, around me, to behold

Rich-robed servants watch and wait?

I so soft a bed to press

While sweet sleep my senses bowed?

I to wake in such a crowd,

Who assist me even to dress?

'Twere deceit to say I dream,

Waking I recall my lot,

I am Sigismund, am I not?

Heaven make plain what dark doth seem!

Tell me, what has phantasy —

Wild, misleading, dream-adept —

So effected while I slept,

That I still the phantoms see?

But let that be as it may,

Why perplex myself and brood?

Better taste the present good,

Come what will some other day.

FIRST SERVANT [aside to the' Second Servant, and to CLARIN]: What a sadness doth oppress him!

SECOND SERVANT: Who in such-like case would be

Less surprised and sad than he?

CLARIN: I for one.

SECOND SERVANT [to the First]: You had best address him.

FIRST SERVANT [to SIGISMUND]: May they sing again?

SIGISMUND: No, no;

I don't care to hear them sing.

SECOND SERVANT: I conceived the song might bring

To your thought some ease.

SIGISMUND: Not so;

Voiced that but charm the ear

Cannot soothe my sorrow's pain;

'Tis the soldier's martial strain

That alone I love to hear.

CLOTALDO: May your Highness, mighty Prince,

Deign to let me kiss your hand,

I would first of all this land

My profound respect evince.

SIGISMUND [aside]: 'Tis my gaoler! how can he

Change his harshness and neglect

To this language of respect?

What can have occurred to me?

CLOTALDO: The new state in which I find you

Must create a vague surprise,

Doubts unnumbered must arise

To bewilder and to blind you;

I would make your prospect fair,

Through the maze a path would show,

Thus, my lord, 'tis right you know

That you are the prince and heir

Of this Polish realm: if late

You lay hidden and concealed

'Twas that we were forced to yield

To the stern decrees of fate,

Which strange ills, I know not how,

Threatened on this land to bring

Should the laurel of a king

Ever crown thy princely brow.

Still relying on the power

Of your will the stars to bind,

For a man of resolute mind

Can them bind how dark they lower;

To this palace from your cell

In your life-long turret keep

They have borne you while dull sleep

Held your spirit in its spell.

Soon to see you and embrace

Comes the King, your father, here —

He will make the rest all clear.

SIGISMUND: Why, thou traitor vile and base,

What need I to know the rest,

Since it is enough to know

Who I am my power to show,

And the pride that fills my breast?

Why this treason brought to light

Has thou to thy country done,

As to hide from the King's son,

'Gainst all reason and all right,

This his rank?

CLOTALDO: Oh, destiny!

SIGISMUND: Thou the traitor's part has played

'Gainst the law; the King betrayed,

And done cruel wrong to me;

Thus for each distinct offence

Have the law, the King, and I

Thee condemned this day to die

By my hands.

SECOND SERVANT: Prince . . . .

SIGISMUND: No pretence

Shall undo the debt I owe you.

Catiff, hence! By Heaven! I say,

If you dare to stop my way

From the window I will throw you.

SECOND SERVANT. Fly, Clotaldo!

CLOTALDO. Woe to thee,

In thy pride so powerful seeming,

Without knowing thou art dreaming!

[Exit.]

SECOND SERVANT: Think . . . .

SIGISMUND: Away! don't trouble me.

SECOND SERVANT: He could not the King deny.

SIGISMUND: Bade to do a wrongful thing

He should have refused the King;

And, besides, his prince was I.

SECOND SERVANT: 'Twas not his affair to try

If the act was wrong or right.

SIGISMUND: You're indifferent, black or white,

Since so pertly you reply.

CLARIN: What the Prince says is quite true,

What you do is wrong, I say.

SECOND SERVANT: Who gave you this licence, pray?

CLARIN: No one gave; I took it.

SIGISMUND: Who

Art thou, speak?

CLARIN: A meddling fellow,

Prating, prying, fond of scrapes,

General of all jackanapes,

And most merry when most mellow.

SIGISMUND: You alone in this new sphere

Have amused me.

CLARIN: That's quite true, sir,

For I am the great amuser

Of all Sigismunds who are here.

SCENE IV.

ASTOLFO, SIGISMUND, CLARIN, Servants, and Musicians.

ASTOLFO: Thousand tunes be blest the day,

Prince, that gives thee to our sight,

Sun of Poland, whose glad light

Makes this whole horizon gay,

As when from the rosy fountains

Of the dawn the stream-rays run,

Since thou issuest like the sun

From the bosom of the mountains!

And though late do not defer

With thy sovran light to shine;

Round thy brow the laurel twine —

Deathless crown.

SIGISMUND: God guard thee, sir.

ASTOLFO: In not knowing me I o'erlook,

But alone for this defect,

This response that lacks respect,

And due honour. Muscovy's Duke

Am I, and your cousin born,

Thus my equal I regard thee.

SIGISMUND: Did there, when I said "God guard thee,"

Lie concealed some latent scorn? —

Then if so, now having got

Thy big name, and seeing thee vexed,

When thou com'st to see me next

I will say God guard thee not.

SECOND SERVANT [to ASTOLFO]: Think, your Highness, if he errs

Thus, his mountain birth's at fault,

Every word is an assault.

[To SIGISMUND.]

Duke Astolfo, sir, prefers . . . .

SIGISMUND: Tut! his talk became a bore,

Nay his act was worse than that,

He presumed to wear his hat.

SECOND SERVANT: As grandee.

SIGISMUND: But I am more.

SECOND SERVANT: Nevertheless respect should be

Much more marked betwixt ye two

Than 'twixt others.

SIGISMUND: And pray who

Asked your meddling thus with me?

SCENE V.

ESTRELLA. — THE SAME.

ESTRELLA: Welcome may your Highness be,

Welcomed oft to this thy throne,

Which long longing for its own

Finds at length its joy in thee;

Where, in spite of bygone fears,

May your reign be great and bright,

And your life in its long flight

Count by ages, not by years.

SIGISMUND (to CLARIN): Tell me, thou, say, who can be

This supreme of loveliness —

Goddess in a woman's dress —

At whose feet divine we see

Heaven its choicest gifts doth lay?—

This sweet maid? Her name declare.

CLARIN: 'Tis your star-named* cousin fair.

*'Estrella', which means star in Spanish.

SIGISMUND: Nay, the sun, 'twere best to say.—

[To ESTRELLA.]

Though thy sweet felicitation

Adds new splendour to my throne,

'Tis for seeing thee alone

That I merit gratulation;

Therefore I a prize have drawn

That I scarce deserved to win,

And am doubly blessed therein:—

Star, that in the rosy dawn

Dimmest with transcendent ray

Orbs that brightest gem the blue,

What is left the sun to do,

When thou risest with the day?—

Give me then thy hand to kiss,

In whose cup of snowy whiteness

Drinks the day delicious brightness.

ESTRELLA: What a courtly speech is this?

ASTOLFO [aside]: If he takes her hand I feel

I am lost.

SECOND SERVANT [aside]: Astolfo's grief

I perceive, and bring relief:—

Think, my lord, excuse my zeal,

That perhaps this is too free,

Since Astolfo . . . .

SIGISMUND: Did I say

Woe to him that stops my way?—

SECOND SERVANT: What I said was just.

SIGISMUND: To me

This is tiresome and absurd.

Nought is just, or good or ill,

In my sight that balks my will.

SECOND SERVANT: Why, my lord, yourself I heard

Say in any righteous thing

It was proper to obey.

SIGISMUND: You must, too, have heard me say

Him I would from window throw

Who should tease me or defy?

SECOND SERVANT: Men like me perhaps might show

That could not be done, sir.

SIGISMUND: No?

Then, by Heaven, at least, I'll try!

[He seizes him in his arms and rushes to the side. All follow, and

return immediately.]

ASTOLFO: What is this I see? Oh, woe!

ESTRELLA: Oh, prevent him! Follow me!

[Exit.]

SIGISMUND: [returning]. From the window into the sea

He has fallen; I told him so.

ASTOLFO: These strange bursts of savage malice

You should regulate, if you can;

Wild beasts are to civilised man

As rude mountains to a palace.

SIGISMUND: Take a bit of advice for that:

Pause ere such bold words are said,

Lest you may not have a head

Upon which to hang your hat.

[Exit ASTOLFO.]

SCENE VI.

BASILIUS, SIGISMUND, and CLARIN.

BASILIUS: What's all this?

SIGISMUND: A trifling thing:

One who teased and thwarted me

I have just thrown into the sea.

CLARIN [to SIGISMUND]: Know, my lord, it is the King.

BASILIUS: Ere the first day's sun hath set,

Has thy coming cost a life?

SIGISMUND: Why he dared me to the strife,

And I only won the bet.

BASILIUS: Prince, my grief, indeed is great,