7 Brand Storytelling

Nathan J. Rodriguez, Ph.D.

“Products are made in the factory, but brands are created in the mind.”

—Walter Landor[1]

First, a Story…

In the late 19th century, a couple of attorneys from Tennessee headed to Atlanta to try to bottle a soft drink.

About a dozen years prior to that journey, the soft drink company sold an average of just nine drinks per day at soda fountains. A year after their successful trip, bottles of Coca-Cola were sold in every state.

However, the company soon had a problem. By the early 1910s, most soft drinks were sold in brown or clear bottles, and Coca-Cola was constantly fending off competitors with names like Koka-Nola, Koke, and Toka-Cola, to list a few, who either copied or closely imitated the Coca-Cola font and logo. Even affixing a newly designed Coca-Cola sticker to the bottle didn’t always work, as bottles were frequently sold in buckets of ice water that caused the labels to peel.

In 1915, Coca-Cola issued a challenge to several U.S. glass companies to create a new bottle—one “so distinct that you would recognize it by feel in the dark or lying broken on the ground.”

The Root Glass Co. in Terre Haute, Indiana, created the winning design after being inspired by an illustration of a cocoa bean. Coca-Cola latched on to the notion of a contoured bottle and had it patented shortly thereafter. Because a shape was being patented, the rights only lasted for 14 years. Coca-Cola managed to renew the patent a couple more times, but by 1951, it had legally exhausted its rights to the shape.

The company then argued the shape of the bottle was distinct enough that it should be given trademark status—something the federal government had not previously granted. Coca-Cola presented findings from a 1949 study that indicated more than 99% of Americans could identify a bottle of Coca-Cola by shape alone. The government agreed, and allowed the company to trademark the bottle shape.

The Takeaway

More than 100 years later, Coca-Cola remains one of the most valuable brands on the planet, due in part to clever marketing appeals and the way it continues to creatively differentiate itself from competitors. It’s a strong, recognizable brand that positions itself to appeal to the largest possible audience.

But what works for Coca-Cola may not work as well for Fanta, Minute Maid Orange Juice, or Powerade—even though all are produced by the Coca-Cola Co.—because each of those beverages has its own history and brand personality. Simply put, brands have a powerful hold on consumers because they are not just a product, but an integral part of pop culture and each individual’s identity.

Introduction to Brand Storytelling

Humans are storytelling animals.[2] We store information and memories in the form of stories.[3]

Consider something you have strong feelings about—a person, product, service, or organization—and chances are, you could tell a brief story that describes what gave you that impression. You might also have told others about a particularly good or bad experience you’ve had.

Today’s brandscape is fiercely competitive, and it’s just not good enough to have an okay product or an okay story. The client must excel at both to stand out. Brand storytelling allows your client to engage a particular audience, creating persuasive appeals that create identification with a consumer, as you may recall from the previous chapter.

But brand storytelling can only go so far, because audiences talk back on social media. If the product or service doesn’t align with the story your client is telling, you’ll hear about it.

Now before you go around telling stories, it’s essential to understand both your client and the target audience first, and then build the brand personality in a way that’s authentic to the client and meaningful to that particular audience. To achieve that, it’s essential to have a solid grasp of consumer psychology and human nature—as well as how stories work—and then apply that knowledge to benefit your client.

What We’ll Cover:

How We Got Here

The idea of brands originated thousands of years ago when livestock owners marked their cattle to indicate ownership.[4] For hundreds of years, artisans offered their own makers’ mark to signify themselves as the producer of items ranging from pottery to glasswork and even loaves of bread.

In the 19th century, the Industrial Revolution brought about standardized, mass-produced goods. Coupled with a growing patchwork of railroads that connected once-distant lands, the change allowed companies to reach new audiences. Companies still needed to build trust with consumers, who were accustomed to purchasing goods locally.[5] By the end of the 19th century, companies began to take steps to differentiate their brand from generic local products.

What started with a simple symbol, name or imprint developed into a logo and stylized company name. Then came paid spokespeople, taglines and jingles.

The 1950s and 1960s are often considered the start of modern-day branding, with some of the largest consumer goods companies like Procter & Gamble and Unilever developing innovative approaches to differentiate their products from others that were functionally the same.[6]

What is a Brand?

A brand “has no objective existence at all: It is simply a collection of perceptions held in the mind of the consumer.”[7]

In one sense, a brand is a combination of the messaging and reputation a company has developed over time.[8] The product and logo are central to a brand’s identity.[9] But it’s also every touch point with a (potential) customer—in person and online—because those experiences shape the perception of a brand.[10]

Impressions of and relationships with brands are formed in a few different ways. Our own experience with products, services, and employees is a significant factor, as is word-of-mouth from those we trust. We also form impressions based on media reports and a company’s messaging and advertising.[11] The combination of those influences result in our having a “gut feeling” about a product, service or organization. When enough people have a similar gut feeling, that’s the brand.

Put another way, “Your brand isn’t what you say it is. It’s what they say it is.”[12]

Understanding Brand-Audience Relationships

We form deep relationships with brands, just as we do with other people.

More than 100 years of studies demonstrate that people tend to assign human-like qualities to everything from food, drink, clothing, tools and weapons[13] to household technologies.[14] It’s human nature to “assign roles, actions and relationships to brands in the stories [we] tell…[our]selves and others.”[15]

We frequently form associations between brands and people in our lives—whether it’s your grandpa’s favorite steak sauce or your ex’s shampoo of choice—and brands originally received as gifts tend to be associated with the giver.[16]

Brands blend into our daily routine. Someone in a strong brand relationship can experience emotions ranging from warmth and affection[17] to passion,[18] infatuation, and selfish, obsessive dependency[19]—to the point that they may have feelings of separation anxiety without it.[20] Consumers don’t just buy brands because they like them, or they work well. They become involved in relationships with brands because of the meaning that’s added to their lives.[21]

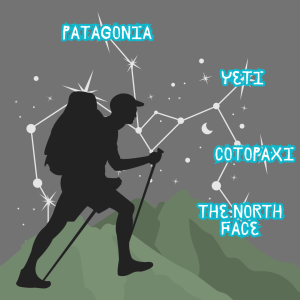

Consumers naturally create “self-brand connections”[22] and assemble “product constellations”[23] to express their social lifestyle. A smaller company that sells kayaks, for example, might therefore circulate images of its product being used alongside a Yeti cooler because the latter already enjoys strong brand equity.

Finally, it’s been said “a brand should not appeal to everyone.”[24] As a general rule, brands that try to mean everything to everyone wind up not meaning very much to anyone in particular. Don’t attempt to accomplish the impossible. Instead, focus on creating a brand that appeals to the beliefs, attitudes, and values of your target audience.

Basic Branding Concepts

It’s important to have a grasp of some key terms in branding because these concepts will help identify where the client excels, and where you can help strengthen their image.

Brand visibility is an all-encompassing term that describes how products or services are presented to audiences. While it isn’t advertising or PR in a traditional sense, it matters to any practitioner and includes everything from sponsorships and giveaways to product placement, naming rights and philanthropy.[25]

Brand equity is the value of a company’s reputation in the marketplace compared to a generic product: Apple and Coca-Cola frequently top lists of the most valuable brands. There are two basic components of brand equity: brand awareness and brand image. Brand awareness is the extent to which someone is familiar with a product or service. Brand image is a comparison of the status and personality of a brand to its competitors.[26]

A brand image includes aesthetics such as the packaging and logo design, and both are incredibly important, as people may forget the name of a product but recall the color of the packaging and look for that when making a purchase.[27]

But there’s more to it.

A brand’s image may be broken down further to include factors such as:

- Brand associations – characteristics used to describe a brand

- Brand loyalty – purchasing habits and attitudes

- Perceived quality – reputation for excellent products and customer experience

- Other proprietary assets – patents, trademarks, relationships that offer a safeguard such that others can’t easily imitate the product. The shape of the Coca-Cola bottle is one example.[28]

That’s a fair amount of abstract terminology, so let’s bring it back to something meaningful: Say you want to order a pizza. Where do you order from and why? You might argue that Pizza Shuttle offers the best option because it’s cheap and delicious (brand association). The weekly special is one of your favorites (brand loyalty). It’s always delivered piping hot and quickly (perceived quality), and the cheese is fresher than anything else in town because it’s sourced from local dairy farmers (other proprietary assets).

Building a Brand

It’s easy for a competitor to imitate a product or service, and as consumers have grown more skeptical in recent years, practitioners have tried to better understand branding and consumer culture.[29]

The foundation of any brand is trust, and trust takes time. The brand will be strengthened if someone has an experience with a product or service that meets or exceeds their expectations. If those expectations aren’t met, they’ll eventually go elsewhere.

To build a brand, start by asking the following three questions[30]: Who are you? What do you do? Why does it matter?

Pro Tip: This is an exercise where you get out of it what you put into it: If you treat the questions as obvious and something to simply get through, your conversation may not yield many meaningful insights. But some innovative ideas might emerge from the process if you approach the questions with the proper blend of research and creativity.

From there, work to create a brand image and personality that appeals to your particular audience. For example, Slim Jim, the purveyor of plastic-wrapped meat sticks found at convenience stores nationwide, speaks to its audience in a way that’s fundamentally distinct from Smartwater or Grey Poupon.

It’s your job to play the role of matchmaker.

New brands should try to distinguish themselves in a way that mimics the lifestyle of the target audience. Established and more mainstream brands generally seek to maintain awareness and reinforce their relationships with a target audience. Finally, a reinvented brand needs to enhance its image due to a crisis or lackluster reputation and generally will require time to repair relationships and improve its standing.[31]

Mottos, Slogans & Taglines

If you’re unclear as to what the difference is between a motto, slogan, and a tagline, you aren’t alone. The terms are often used interchangeably in practice because they all involve a short, memorable phrase. But there are differences.

Just as a person may have a motto by which they live their life, a brand’s motto is a short phrase that describes its values and guiding principles. Amazon adopted “Work Hard, Have Fun, Make History” as its internal motto.

A slogan was originally defined as a rallying battle cry, and it hopes to achieve a similar response metaphorically.[32] It’s a brief, memorable phrase used for temporary purposes, usually to sell a particular product.[33]

A tagline, while similar to a slogan, is more permanent, and intended to raise overall awareness of a brand.[34] Taglines are therefore seen as more PR-oriented than slogans, which historically fell into the realm of advertising and marketing.

For example, you may have heard the slogan: “Believe in something, even if it means sacrificing everything.” Or perhaps “Greatness is not born, it is made.” Or maybe “Start unknown, finish unforgettable.” Maybe not. But chances are you’re familiar with the tagline “Just Do It.” All three slogans were used in individual campaigns by Nike, which, of course, has kept its tagline for decades.

Nike’s “Just Do It” is widely considered as one of the best taglines for a product. Here’s a quick origin story: The creatives at Wieden + Kennedy happened to see the last words of convicted murderer Gary Gilmore were “Let’s do it!” prior to his 1977 execution by firing squad in the state of Utah.[35] Inspiration can come from odd places. As far as the iconic “swoosh” is concerned, Carolyn Davidson, the graphic design student who created it in 1971, was paid a grand total of $35 for her design.[36]

There are five types of taglines.[37] Imperative taglines command action and usually start with a verb (Apple: “Think Different”; YouTube: “Broadcast Yourself”). Descriptive taglines describe the service, product or brand promise (Target: “Expect More, Pay Less”; Allstate: “You’re In Good Hands”). Superlative taglines position the brand as the best in its class (Budweiser: “King of Beers”; BMW: “The ultimate driving machine”). Provocative taglines are thought-provoking and commonly ask a question (Dairy Council: “Got Milk?”; Capital One: “What’s in Your Wallet?”). Specific taglines reveal the business category (Volkswagen: “Drivers Wanted”; The New York Times: “All the News That’s Fit to Print”). These categories overlap, as Olay’s “Love the Skin You’re In,” for example, could be seen as imperative, descriptive, provocative, and specific.

Crafting a brief, memorable phrase that conveys the essence of a brand is critical: “No principle moves the sales needle more than achieving simple clarity.”[38]

Simplicity may be easy to understand, but it’s difficult to execute.

Checklist for a Quality Tagline[39]:

[ __ ] Short (usually three to six words)

[ __ ] Differentiated from competitors

[ __ ] Captures the brand essence

[ __ ] Easy to say and remember

[ __ ] No negative connotations

[ __ ] Readable in a small font

[ __ ] May be protected/trademarked

[ __ ] Evokes an emotional response

Hashtags are often a simplified variant of a slogan or tagline, and can be deployed strategically to capitalize on a trend or reinforce the brand image. They may also be used whimsically to avoid being seen as “trying too hard,” which generally isn’t a good look for anyone online.

Brand Personality & Brand Voice

The next step is understanding how to position the brand’s communication strategically.

If your product or service is the cheapest on the market, congrats on finding your niche—take the rest of the day off! Everyone else needs to carve out space in the marketplace of ideas and find ways to authentically represent your brand in a way that connects with your audience.

The brand voice is the overall tone in public-facing communication. Brand voice ranges from the words and phrases a company uses to visual dynamics like font choice or color. For example, look at the differences between Apple and Microsoft. Apple is distinct for its use of white space and minimalism. In contrast, Microsoft is synonymous with blocky infographics and pastel colors.

On social media, companies may verbally communicate in ways that are professional, snarky and spunky, product- and brand-focused, audience-focused, inspirational, conversational, witty, educational, or personality-focused.[40] The tone must feel authentic to the brand and must be natural rather than forced. It should also be consistent across all platforms and sustainable for those who communicate on behalf of the brand.[41]

To help find your brand voice, first think of the brand in terms of personality attributes—what it is, and is not. Next, reflect upon how audiences feel about your content, and what they get from the relationship. Then, examine your competition: How they communicate, their overall tone, and how you’d describe their brand voice. Finally, consider your goals for your content and the audience’s response to that content.[42]

The goal is to develop an appealing and consistent brand personality. A brand personality may be considered the sum of all actions by a particular entity,[43] as interpreted by members of the target audience.

One shortcut to humanizing a brand is partnering with spokespersons and influencers. We’ll dive into influencers in the next chapter, but for now, understand there might be drawbacks to tying the brand to a particular individual.

If your proposal is to “Just add influencers,” it may work, but that alone is underwhelming. It’s far more effective and satisfying to first cultivate a brand personality, and later focus on the method of delivery.

Experts Talk Back:

Interview with Frank Vamos, vice president of global strategic communications & creative storytelling at Wendy’s.

Q: Wendy’s is known for its social media presence. How was the brand voice developed?

We got into a bit of an exercise a few years back looking at the history of Wendy’s and getting to know our brand inside and out. We looked at past communications to better understand those media channels, and understanding when Wendy’s was at its best, and it was true to the foundation of why we were created and who we were, and trying to understand that, and what position we held against our competitors that we truly believed in. And as we looked at those communications, when were we—in our own view—at our best? And how would we define what “at our best” looked like in those communications?

If you recall, some of the Dave Thomas commercials existed a number of years back, but you had some of those commercials like “Where’s the beef?” and there was a chicken “Parts is parts” commercial, and with each of them, what began to come through pretty quickly was it was never a “We’re This; They’re That” kind of commercial. In “Where’s the beef?” at the heart of it, Wendy’s was saying, “We have more beef in our hamburgers than McDonald’s or Burger King or any other competitor.” We could have come out and just done a “This or That” type of comparison, but that’s not traditionally how we communicate.

We found the way to use our founder as a reflection of the brand is to say, “Hey, this is who we are.” We’re going to be a voice for customers in pointing out what we see is a failure in the industry. Others are hiding the amount of beef they’re providing in a hamburger and trying to cut costs, and that’s just not Wendy’s. But we found the right way to do it. We refer to that voice as a little bit sassy, and really are identifying the right way to do that.

Fast forward to the social communications. A few years ago, McDonald’s announced they were going to release fresh beef in quarter-pounders in some of their restaurants. We called ‘em out, but in sort of the “Where’s-the-Beef” version of that: “@McDonalds So you’ll still use frozen beef in MOST of your burgers in ALL of your restaurants? Asking for a friend.”

So it was that tone. We could have just issued a more formal response, but that wasn’t Wendy’s voice. So it was us again standing up to what we believed was a half-truth from a competitive brand and being true to the voice of Wendy’s to call that out.

Social has really been a great piece for Wendy’s to communicate. We’ve worked at it really hard over the years to make sure that it’s not a social voice, it is our brand voice that comes to life in social. So we spent a lot of time figuring out what that voice was—when was Wendy’s at its best—to do it, and we try to bring that every day to social.

“It’s not a social voice, it’s our brand voice that comes to life in social.”

Q: You described it as a sassy voice. How receptive were other executives at Wendy’s when you were suggesting this particular type of online style? Was there much pushback, or did it require explanation, or did they just sort of jump in and agree with the direction?

Social was a little under the radar. It wasn’t seen as this powerful mechanism, so we had the opportunity as a team—and there were a lot of great individuals involved—to kind of grow it slowly, and under the radar. They knew we had it, and we probably weren’t as sassy out of the gate, but it really was built on—and credit to a number of individuals here—staying true to how the Wendy’s brand seemed to operate, which was focusing on the individual and recognizing them for who they were.

And that leads to a lot of things being born into our brand position of how we define our brand, but when it really came to social, it was about, “Hey, make friends and invite them to lunch,” instead of selling to them directly, and so that’s the language and the motto that we tend to embrace.

So how do you do that if that social user’s talking about movies? How do we meet them on their ground in conversation and not just blast marketing messages at them? How do we make that connection to show that we understand who they are as individuals or as consumers? Now the hard part is we still sell hamburgers every day, so that is where our bread and butter is, but trying to understand and to operate in that world in the right way was really important to us.

Q: Is there anything else you’d like to add?

As a communications guy, I’m always fascinated by how other brands do it, and for Wendy’s, if it’s right for the brand; it’s right for us. We’ve had other brands approach saying, “Well, what’s your playbook look like?” And it doesn’t make it a playbook that’s right for other brands. I think finding that interaction and finding what your business is about and what feels right has been good for us.

Features, Benefits & Narrative Persuasion

When you deeply understand a brand, it’s tempting to focus on the features of that product or service rather than how the audience will benefit.

Not everyone knows why it’s good to have a vehicle with a two-axle drivetrain that can provide torque to each wheel simultaneously, but just about everyone can understand the benefits of four-wheel drive if it’s put in the context of safely navigating loved ones through adverse road conditions. Focus on the benefit, not the feature.

Narrative persuasion is powerful because audiences “counter-argue” less with stories compared to more direct forms of persuasion.[44] In recent years, practitioners and academics have warmed up to the notion that images, phrases and advertisements should be considered narratives—and narrative persuasion is “any influence on beliefs, attitudes, or actions brought about by a narrative message.”[45]

To craft an effective narrative, you need to appreciate basic story archetypes and identify the inherent drama in your product or service.

Client Activity: Discovering Deep Metaphors

In Sticky Branding, Jeremy Miller argues that great brands are built on deep metaphors, and brands should build stories around archetypes rather than stereotypes. Archetypes are universal themes that include deep metaphors. Deep metaphors are intuitive and immediately understood so as to require no explanation.

He uses a technique created by Gerald Zaltman at Harvard Business School in the mid-1970s. The idea is that humanity shares seven deep metaphors: balance, transformation, journey, container, connection, resource and control.

A quick rundown:[46] Balance involves ideas of equilibrium, adjustment, and being either centered or out-of-sorts, and on- or off-track. Transformation refers to changing a state or status in life. A journey is often a metaphor for life itself. A container keeps certain things in and other things out. Connection concerns belonging and exclusion. Resources are key to survival, and those can sometimes be particular products or services that are essential to something functioning well or making life better. Control relates to our desire to feel that our affairs are in order.

For example, Snickers uses balance/imbalance when it claims, “You’re not you when you’re hungry,” as their commercials typically show a protagonist acting out-of-sorts due to hunger, which is resolved by a quick nibble of a candy bar. Toyota emphasizes the journey metaphor in its advertisements and tagline, “Let’s Go Places.”

To figure out your client’s deep metaphor, ask the staff, customers, suppliers, and others to work through the following steps[47]:

- Pick a story: The story should be about the company and one that’s meaningful to them. For example, it could be about how they first encountered the company, how they felt about it, or how they use the product/service.

- Select pictures: Next, have them find five to 20 images to tell their story. They won’t be telling us a traditional story—they’ll tell it with pictures. Tell them to think of it as a slideshow. This helps the storyteller be more descriptive about their experience.

- Share the story: Give them 15 minutes to tell their story and be as thorough as possible. Let ‘em have fun with it and encourage them to make it an epic tale. Be sure to ask them to explain why they chose particular images and what each represents.

- Listen: Observe and be very patient. Be present, don’t judge, and pay close attention to the details they provide. Take notes. Write down the words and phrases they use.

- Identify commonalities: What are the common phrases, descriptions, or metaphors they used? Highlight those.

- Find the deep metaphors: Which ones come up most frequently? Look at the most commonly used phrases and try associating a deep metaphor with each one.

- Pick your metaphor(s): Which ones best fit the brand? Limit it to a primary and possibly a secondary metaphor. Anything more than that will clutter the message.

- Use the Metaphor(s): Build the deep metaphor into the website, logo, marketing materials, and everything your brand touches. The idea is to consistently present deep metaphor visuals.

Note: There is no “official” list of archetypes. Some say there are seven basic story archetypes.[48] Consumer storytelling theorists, who focus on consumer psychology, have argued there are a dozen archetypes and “story gists.” [49]Other observers argue that by examining storytelling in literature, we can identify 20 master plots, which can be utilized by organizations.[50] The list above is a solid start.

Brand Storytelling

Brand storytelling doesn’t just take place on social media. It can and should inform everything from the “About Us” or “History” tab on a website, to advertising, internal messages, annual reports, feature writing, news releases, and public speeches.[51]

Stories have two key elements: chronology and causality.[52] In other words, certain actions occur over a period of time. Stories need to make sense, be believable and resonate with an audience’s belief.[53] A well-told story expresses how and why life changes, and is a struggle between expectation and reality.[54]

“Desire is not a shopping list, but a core need that, if satisfied, would stop the story in its tracks.”

—Robert McKee

Brands can leverage storytelling techniques effectively in ways that (1) allow users to be part of the experience; (2) listen to their audience and create relevant content; (3) highlight the brand’s values; and (4) share the brand’s perspective.[55]

When crafting the narrative, consider the “inherent drama” of a product or service: What makes it interesting or unusual, and how would that benefit the target audience?[56]

Stories also need indices and antagonists. Indices are the “locations, decisions, actions, attitudes, quandaries, decisions, or conclusions” in a story, and the more indices that are included in a story, the more likely it is that someone will remember the story.[57] An antagonist is whatever prevents the protagonist from achieving their desired outcome, and it may be “people, society, time, space and every object in it or any combination of these forces at once.”[58]

One final distinction to consider is whether your narrative messaging comes across as a lecture or a drama. Lectures are intended for an audience, but dramas are overheard by an audience.[59] A host of studies have shown that learning through storytelling is “more memorable and retrievable” than lecture-based learning, and that drama-based advertising is “more effective in situations reflecting everyday life” than lecture-based advertising.

Show, don’t tell.

Summary: Putting It All Together

The basic goal is to “create a living, breathing brand with a simple story at its core and a constantly changing set of products or services that are worth keeping an eye on.”[60]

You are the matchmaker between a brand and a particular audience.

First, research and ask questions to understand the brand and the audience. What does the brand mean to the people who should care most about it?

Then, work to build meaningful connections between the brand and the audience. All brands are built on a collection of experiences, and your job is to figure out what makes your brand better and “bake that into the customer experience.”[61]

Embrace simple clarity and focus on the benefits of a service or product rather than the features. Cultivate a brand personality that’s authentic, deploy deep metaphors in your communication, and tell your story every chance you get—online, offline, internally and externally.

Beyond telling its story, the brand must live its story. Audiences talk back and will eventually figure out if a brand’s story about itself is a work of fiction. Creatively telling a true story allows a brand to be relevant and endure.

Media Attributions

- Coke winning design is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Bass Brewery is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Tide is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Product constellation © Alexis Kiedaisch is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- Jared Fogle © Late1 is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- “Walter Landor,” (n.d.), Area of Design. Retrieved from: https://areaofdesign.com/walter-landor/ ↵

- Fisher, “Narration,” 1-22. ↵

- Woodside, “Brand-Consumer Storytelling,” 532; Kent, “Storytelling in PR,” 480-489. ↵

- Ammerman, “Invisible Brand,” 8. ↵

- Tedlow, “Marketing History,” 11-14. ↵

- Arons, “How Brands Were Born” ↵

- Fournier, “Consumers and their brands,” 345. ↵

- Zitron, “This is How You Pitch,” 64 ↵

- Brunner and Hickerson, “Cases in PR,” 325. ↵

- Miller, “Sticky Branding,” 14. ↵

- Falkheimer and Heide, “Strategic Communication,” 8. ↵

- Neumeier, “The Brand Gap,” 2-3. ↵

- Fournier, 345. ↵

- Mick and Fournier, “Consumer Cognizance,” 141. ↵

- Woodside, Sood, and Miller, “Storytelling theory and research,” 101. ↵

- McGrath, Sherry, and Levy, “Giving Voice to the Gift,” 178-189. ↵

- Perlman and Fehr, “Intimate Relationships,” in Fournier, 364. ↵

- Sternberg, “Triangular Theory of Love”; Shimp and Madden, “Consumer-Object Relations,” 163-168. ↵

- Lane and Wegner, “Back Alley to Love,” in Fournier, 364. ↵

- Berscheid, “Emotion,” in Fournier, 364. ↵

- Fournier, 360-361. ↵

- Escalas, “Consumer connections to brands,”176-177. ↵

- Solomon & Assael, “Symbolic consumption,” in Fournier, 367. ↵

- Juska,”Integrated Marketing Communication,” 85. ↵

- Juska, 5. ↵

- Blakeman, “Integrated Marketing Communication,” 46-47. ↵

- Blakeman, 49. ↵

- Aaker, “Brand Equity,” 3. ↵

- Falkheimer & Heide, “Strategic Communication,” 62. ↵

- Neumeier, 50. ↵

- Blakeman, 49-50. ↵

- Bellak, “Nature of Slogans,” 497. ↵

- Rosie, “Slogan and Tagline.” ↵

- “Tagline vs. Slogan.” ↵

- Art & Copy. ↵

- A dozen years later, Nike honored her at a reception, giving her a diamond ring with a swoosh on it, as well as 500 shares of the company. At that time, those shares were worth less than $100. Today, after stock splits, those shares are now worth approximately $4 million. ↵

- Wheeler, 2013, p. 25 ↵

- Miller, pp. 37-38. ↵

- Wheeler, Designing Brand Identity, 29 ↵

- Freberg, “Social Media,” 148-153. ↵

- Freberg, 55. ↵

- Freberg, 144. ↵

- Olson & Allen, “Building bonds,” in Fournier, 345. ↵

- Bilandzic and Busselle, “Narrative Persuasion,” 201. ↵

- Bilandzic and Busselle, 201. ↵

- “Deep Metaphors.” ↵

- Miller, 80-81. ↵

- Booker, The Seven Basic Plots, 5-7. ↵

- Woodside, Sood, and Miller, 103. ↵

- Kent, 487-488. ↵

- Kent, 486-488. ↵

- Delgadillo & Escalas, “Consumer Storytelling,” 186. ↵

- Fisher, “The Narrative Paradigm,” 349-350. ↵

- Woodside, 535. ↵

- Freberg, 21-22. ↵

- Blakeman, 74. ↵

- Woodside, 532. ↵

- Woodside, 535. ↵

- Wells, 1989. ↵

- Zitron, 68. ↵

- Miller, 82. ↵