6 Persuasion, Identification & Framing

Nathan J. Rodriguez, Ph.D.

“Let’s not forget that the little emotions are the great captains of our lives, and we obey them without realizing it.”

—Vincent Van Gogh

First, a Story…

Kenneth Burke was unsuccessful as a college student.

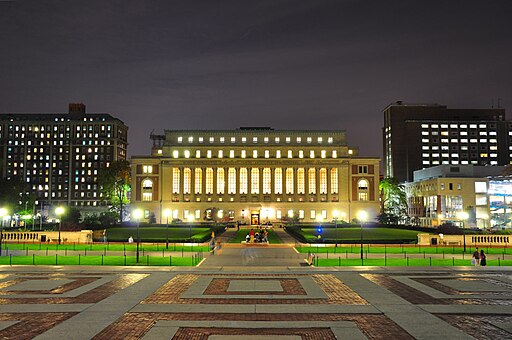

He enrolled at Ohio State for a semester, then dropped out. He then attended Columbia University for a couple of years, but became frustrated by the number of prerequisites needed just to enroll in classes he actually wanted to take.

He got in touch with his dad, who was financing his education and said, “I know how to save you some money.”[1]

Kenneth persuaded his dad to rent him a room in New York City near the university library. He wanted to read the books himself at his own pace — and instead of treating them as an end point, the knowledge gained became a springboard for additional research and thought.

He became friends with avant-garde writers in New York City and broadened his horizons. Kenneth never graduated from Columbia, but when he emerged from its library, he had a great deal to say about the nature of knowledge itself.

He questioned scholars who argued that logical arguments formed the basis of persuasion. He argued identification was a prerequisite for persuasion, claiming it was only possible to persuade someone “insofar as you can [speak their] language by speech, gesture, tonality, order, image, attitude, idea, identifying your ways with [theirs].”[2] Through identification, one hopes to achieve a feeling of shared interest and common ground.

The Takeaway

The most logical, coherent appeals may not be enough to persuade someone if they view you as an outsider trying to sell them something. You have to speak their language and demonstrate you understand their situation. That allows you to focus on shared interests and values in an authentic and meaningful way. A successful outcome is more likely when persuasive appeals are rooted in common ground.

Our college dropout changed the game for rhetoricians (i.e., teachers of public communication) and anyone interested in persuasion. As a self-taught scholar, he became one of the most well-known and respected thinkers of the 20th century, and academic conferences devoted solely to his work continue to this day.

Introduction to Persuasion, Identification & Framing

This chapter is edgy.

It’s edgy because there remains a lively debate as to whether persuasion actually has a home in Public Relations and Strategic Communication, and if it can be deployed in an ethical manner.[3]

Let’s short-circuit that debate.

Strategic Communication and persuasion are functionally indistinguishable. To suggest otherwise is to show up to a mixed martial arts fight, ready only for bare-knuckle boxing.

Persuasion can be ethical, whether it’s talking someone off a building ledge or advocating for a local food bank.[4]

Ethical persuasion isn’t a tool of naïve communicators, it’s what works. As a practitioner, it’s your job to play matchmaker for your client and their target audience. You want to build authentic relationships that will endure. The messaging must emerge from something genuine.

Welcome, my friends, to the world of persuasion.

What We’ll Cover:

How We Got Here: Rhetoric, Persuasion & PR

Aristotle defined rhetoric as the art of discovering, in any particular case, all the available means of persuasion within a given situation.

Rhetoric originally focused upon the spoken word — primarily speeches — until the 20th century when the field became more interdisciplinary and included persuasive writing.[5]

Our friend in the opening anecdote, Kenneth Burke, is credited with creating a transition between “old” rhetoric that focused on persuasion, and “new” rhetoric that approached it in terms of identification.[6] He broadened the traditional view of rhetoric as persuasion to include “virtually any means of ‘inducing cooperation and building communities.’”[7]

Finally, toward the end of the 20th century, rhetorical scholars recognized that the audience shouldn’t be viewed as singular and unified, but “multiple and conflicted, composed of numerous … positions.”[8] As mentioned earlier in this book, our audience is not a public but multiple sets of publics.

The idea of building communities is, of course, key to virtually every PR effort. And the view of the audience as multifaceted is a guiding principle of Strategic Communication. It therefore stands to reason that PR and Strategic Communication practitioners could adapt some ideas from rhetorical scholars and behavioral scientists, just as they have borrowed ideas from business and marketing for decades.

The distinction between the general public and particular publics — or the target audience — is more obvious today, thanks to the influence of social media. It’s the difference between watching the nightly news on television, and scrolling through your newsfeed on a social media platform. The former is able to speak to a broad audience, and the latter feels as though it’s speaking directly to you.

To craft tailored messages, you’ll use the persuasive concepts of identification and framing.

Understanding Audience Motivations

Before considering the framing and phrasing of your message, you need to first appreciate what motivates the target audience.

What goals do they have when they interact with your content or product?

When you first ask that question, you might get an answer like “to get more information” or “to laugh.”

Don’t stop there.

The trick to understanding consumer behavior is to ask, “Why is that important?” after each of the first three responses.

For example, you could ask someone why they chew gum. They might respond that it keeps their breath fresh. And why is that important? Because we don’t want to have bad breath when someone is close to us. And why is that important? Because we want to be liked by other people. And why is that important? Because we want to connect with other human beings in meaningful ways.

Things got real, pretty quickly. And that was just chewing gum!

While that may seem like an abstract example, it translated well. Extra won audiences over with a two-minute spot that depicted a love story and featured gum as a key plot device:

Motivational States

Behavioral science attempts, in part, to understand what motivates consumers and why people make certain choices.

In the book Marketing to Mindstates, behavioral scientist Will Leach contends that you first need to evaluate the overall context of the consumer in terms of location (where someone is when they make a decision), people (who they’re with when that decision is made), feeling (how they are physically and emotionally at that moment), and framing (how choices are presented in the moment of a decision).[9]

“Behavior design is part intuition, part artistry, and part science, all merged together to influence the heart and the mind. It doesn’t replace design or great marketing — it builds on it.”

—Will Leach[10]

After the context is understood, identify the points at which someone might be the most receptive to persuasion. Ask yourself, or a focus group, about the goals the consumer is trying to reach in that particular moment. Use the “Why is that important?” technique to identify consumers’ emotional goals and focus on those. Evaluate that mindset and either lean into it or help create it.[11]

Leach combined more than 30 years of motivational psychology and generated a list of nine motivational states.[12] A brief description of each is below, as well as examples of companies that tend to tap into that particular motivational state.

1. Achievement: Being successful and proud by overcoming obstacles

(Nike, Bosch Power Tools)

2. Autonomy: Independent, unique, having options

(Lego, boutique store brands)

3. Belonging: To be accepted by and connected with others

(Harley-Davidson, CrossFit)

4. Competence: Being prepared, qualified, and skilled

(Microsoft, Home Depot)

5. Empowerment: Feeling equipped to act upon a desired choice

(Schwinn Bicycles, Patagonia)

6. Engagement: Being excited about or interested in an activity, nostalgia

(IKEA, Disney)

7. Esteem: Being approved of, respected, or admired by others

(BMW, Chanel)

8. Nurturance: Being loved and taken care of, and able to care for others

(Gerber, Hallmark)

9. Security: Being protected from threats

(ADT, Allstate Insurance)

These categories overlap, but most decisions are associated with at least one and as many as three motivations.

So in the moment that a consumer interacts with your brand’s content, product or service, which motivations best describe how they want to feel?

“The part played by the unconscious in all our acts is immense, and that played by reason very small.”

—Gustave Le Bon, The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind (1895)

Motivations vary dramatically, and different motivations require different messaging strategies.

As Leach pointed out, people may purchase organic food due to belonging and a desire to be part of something larger than themselves, or it might be due to nurturing and a desire to not have chemicals in their family’s food.[13]

From there, craft the messaging in a way that taps into that specific mental state. To do that, you’ll need to consider both substance and style, what you say and how you’ll say it. In other words, you’ll need to consider framing and phrasing.

Framing and Phrasing: A Quick Overview

How’s it going?

It’s one of the most basic questions we ask one another.

A typical answer might be “good” or “not bad” if the question was viewed as a brief greeting. If it’s someone you have regular contact with, you might offer a few more details about school, work, or people you both know. A favorite professor always responded, “I’d be ashamed to complain.”

But in all cases, the response involves framing and phrasing. Framing is the way in which something is characterized, and phrasing is the precise word choice that forms that characterization.

From there, we can expand that idea to all language. As Burke pointed out, language doesn’t just reflect reality, it selects and deflects it.[14] The easiest way to think of Burke’s metaphor is that it functions like taking a photo. You capture reality, but only a select part of it, because you cannot capture everything. At the same time, you might choose to deflect something in the image by cropping the photo or fixing a flaw through editing software.

Let’s put framing into practice. If we were to ask a coworker how their vacation went, their response typically would go beyond “good” or “not bad,” and the framing and phrasing choices become more obvious. And Burke’s observation about language reflecting, selecting and deflecting reality becomes clear as well. The coworker may have had a good time overall (reflecting reality), but any rundown of activities or sightseeing is limited at best (selecting reality), and they may leave out unpleasant aspects like people being in a bad mood (deflecting reality).

The PR-specific literature on framing doesn’t contribute much to the conversation. A handful of scholars examined whether messages about the cost of not acting were more effective than messages about the benefits of taking action, and concluded there was “no overall difference.”[15] Different situations call for different methods of persuasion.

“The difference between the almost right word and the right word is really a large matter—‘tis the difference between the lightning bug and the lightning.”

—Mark Twain

The takeaway is that precise language is essential for any message to connect. Messages need to be framed and phrased in ways that are meaningful to the target audience.

And while there’s no substitute for researching all there is to know about your target audience, there are a handful of theories about what tends to work. The methods of communicating messages may change, but human nature is remarkably consistent.

Experts Talk Back:

Three Questions with Ian Anderson, Partner and Vice President of Public Relations at Backbone Media.

Backbone Media works with several dozen clients including the American Pistachio Growers, Breckenridge Tourism Office, Brewer’s Association, Chacos, Columbia, Eddie Bauer, Fleet Feet, Klean Kanteen, mongoose, Mountain Collective, Nike Vision, ooni pizza ovens, Patagonia, Pendleton Whisky, Pickleball Central, Public Lands, Saucony, Schwinn, Sea-Doo, Ski-Doo, Smartwool, Tecovas, Thermacell, Thule, The Wilderness Society and Yeti.

Q: How do you approach the positioning of a brand in relation to its audience?

Oftentimes the brand has worked with an agency or just has an established position that they have really held true to for many, many years.

If you take a brand — Filson, for example, it’s a brand that’s been around for well over a hundred years, based in the Pacific Northwest and it’s really focused on making apparel and gear for the outdoors that’s built to last. And so for Filson we don’t change their positioning. We’re not looking to — in any way, shape or form — take away from their credibility that they’ve worked to establish forever. But what we might do is fine-tune the positioning based upon the audience.

And for us, generally speaking on the PR side, what we do is we’re working with writers and editors. And those writers and editors often are covering a certain type of story. They have a specific beat, and so we are looking to find stories that align with what they typically write about.

And so that’s where we may take one aspect of a brand’s story, whether that’s an athlete that they sponsor or support, whether it’s a nonprofit they partner with, whether it’s part of a larger trend — with Filson, that may be U.S. manufacturing, or it might be particular trends around DEI, for others it might be something that’s focused on sustainability. So, we’re positioning those clients so that it fits within the kind of story parameters that are hopefully going to be compelling for a journalist that we’re targeting for the story.

Q: It’s been said that consumers create a constellation of brands or products that are part of their lives. You have clients ranging from Patagonia to pistachios. Do you find that when you have a smaller client, you could say, “Hey, you could take a picture with a Yeti in the background,” since they’re another one of your clients — do you try to create that sort of synergy, or do you remain focused on one particular brand at a time?

At the end of the day, since the beginning of time for public relations, it’s been about relationships.

One way that we’ll build relationships with key targeted media is try to get out into the outdoors, and especially around product launch, we’re looking to take that product into the environment for which it’s designed.

So, whether that’s going on a backcountry ski trip, whether that’s going on a float, whether that’s going on an early morning trail run, we are taking the product and putting it on to the feet, the bodies — or whatever the product may be — we’re putting it onto the writers and editors, who will then hopefully review it and write stories about it.

So, we design press trips. For us, certainly we saw fewer press trips during the pandemic, but it didn’t mean they stopped, and they’re kind of roaring back. At this point in time, I think we have close to two dozen press trips scheduled in the next couple of months, and some of those press trips are kind of smaller group activities where it’s a lot of one-on-one kind of trips, and others are bigger, more exotic trips where we’re going to a really cool destination, and we’re taking eight to 10 journalists.

And in nearly every single scenario, there generally is one of our clients who has a brand-new widget that they are looking to get publicity around, but whenever we can bring other clients’ products along, and complement that new product, that is a win-win. It’s cost-effective for our clients because often some of the hard costs behind those press trips can be shared between brands, and then it’s beneficial for the journalist so if they are going to take some time out of the office, whether that’s their home office or corporate office, they then can find opportunities to write more than just one story. They can test four or five different products in one fell swoop, then they can come back and have lots of review opportunities to follow-up with down the road.

Q: What advice would you have for students who would be graduating in the next few years and want to work in the PR or Strategic Communication field generally?

Certainly, I think the landscape continues to change, but there are some fundamentals that are important. When we’re looking at candidates — again, kind of on the PR side of our work — there’s a couple of skill sets that are really critical.

The first is just basic communication skills, and that means that certainly we need people with strong writing skills. We are pitching to professional writers all day, every day. Most of the pitching that we do is via email. Sometimes we do pick up the phone and call folks, but the majority happens via email.

So, the emails we write don’t always have to be formal, but they have to be compelling and they have to be accurate. And you lose credibility as a PR professional pretty quickly if you’ve got poor grammar, if you write run-on sentences, if you can’t get your point across in a concise, compelling way.

So that’s really critical, and communication skills certainly extend to good people skills. We do a lot of stuff in person, and so kind of understanding that customer service gene is really critical for us. And in those trips, those one-on-one’s that we plan with journalists, we are basically their hosts, and so it’s important to show them a really positive experience in order to paint the product and the brand in the most positive possible light. And so that communication side of things is really important.

And then for our agency, authenticity is just critical for us. For the brands that we represent, we try to really pair people’s personal passions with the brands they work with. And so, the folks who work on Black Diamond are backcountry skiers and rock climbers and trail runners. Our team that works with even something like ooni pizza ovens, they love to cook. And so they get to talk about that product in a very first-person kind of way. They’re out testing and using the product on their own time and when they are pitching to the media, they can talk about it from a place of credibility. And that really shines through. They’re not reading from a spec sheet, they’re not just using whatever the pre-approved talking points are, they’re really talking about it from their own personal experience.

Framing the Message: The Psychology of Persuasion[16]

In the 1980s, Robert Cialdini developed what he referred to as the six universal principles of influence, based on years of research: reciprocity, consistency, social proof, authority, liking, and scarcity. His work has been cited tens of thousands of times over the past few decades by scholars in a range of fields from PR and marketing to rhetoric and consumer behavior.

Reciprocity is the idea that people feel a sense of obligation to repay something they’ve received from someone else. For example, surveys sent in the mail that include a small amount of money are more likely to be filled out and mailed back by the recipient. But it also applies to someone who has said “no” to a particular ask, as they may be more likely to say “yes” to a smaller ask—which goes back to our “foot in the door” and “door in the face” approaches.

Consistency is a common motivation in that people like to be in line with their past beliefs and behaviors. This can include making a public commitment to something, whether it’s a personal goal or a particular cause. It’s also shown up in research where people who sign petitions in favor of a particular issue were more likely to donate money two weeks later. When presented with an opportunity to be consistent with past behavior, people tend to take it.

To sum up social proof in just four words: “Monkey See, Monkey Do.” We have a lot going on in our lives, and we can’t research absolutely every action we take, so we tend to follow the lead of others. Studies have shown that people were more likely to donate to a local charity when presented with a list of their neighbors that had donated.

Authority refers to someone’s perceived expertise and trustworthiness in a particular situation. Companies that have been around for several decades typically lean into that. Expertise refers to how qualified someone might be based on their credentials and experience. But trustworthiness is an equally important factor as well. It’s the difference between finding a mechanic, and finding a mechanic you’ll return to.

Liking may be obvious, but people are more likely to agree with and say “yes” to someone they like. This includes less controllable interpersonal factors like physical attractiveness, but also includes a demonstrated willingness to cooperate. More importantly, similarity to and shared interest with the target audience — what Burke would call identification — is an entry point for any persuasive appeal.

Scarcity is the notion that as items and opportunities become less available, they become more attractive. If something is produced for a limited time, or in a limited edition, they tend to attract more attention. There are dozens of studies that demonstrate this effect across multiple industries, but one attention-grabbing technique in recent years has been to offer a silly or absurd — or perhaps brilliant — product in limited quantities. KFC earned substantial free media coverage by announcing its fried chicken-scented bath bomb in Japan.[17]

Some of these persuasive concepts can be directly applied in interpersonal situations. But a good chunk of PR is developing mutually beneficial relationships. And the more you can utilize these principles in framing and phrasing of your messages, the more likely it is that those messages will connect.

Phrasing the Message: Purpose, Audience & Method

Once you’ve figured out what you want to say, what’s the best way to say it?

As we learned with identification, the best way to connect with someone is to share common ground and speak in a way that feels authentic and in touch.

Each time you formulate a message in Strategic Communication, consider three things: purpose, audience and method.[18]

The purpose is what you hope to achieve. The audience is who you’re trying to persuade. The method is the way you interact with them.

For example, Petco may want its customers to donate to local animal shelters. The framing and phrasing of that particular request to customers will vary if the method of delivering the message was face-to-face at a checkout line, through an email blast, on a billboard, or in a 6-second spot on social media.

There’s no shortage of useful theories in PR and Strategic Communications.

Considering the purpose, audience, and method is perhaps the simplest but most useful approach that can improve the outcome of any effort at communication. So, if your messaging or your thinking ever gets too cluttered, bring it back to the basics: What are you trying to accomplish? Who are you trying to reach? How are you trying to reach them?

The answer to those questions should lend a hint at how to frame and phrase your persuasive appeal. And that’s really what it’s all about. Remember the closing words of Chapter One: The functional aim of Public Relations and Strategic Communication is to communicate the right message at the right time in the right place to the right audience.[19]

Summary: Putting it All Together

Persuasion and Public Relations are intertwined, and even indistinguishable at times, from one another.

Before you can persuade a member of a target audience, that person has to identify with the messenger.

To promote identification, first examine the context (location, people, feeling, framing of choices) from the consumer’s perspective. Figure out the goal the consumer is trying to reach through the “Why is that important?” series of questions. Identify their motivational state, and then craft messaging that taps into that specific mental state.

From there, it comes down to framing and phrasing the persuasive appeal. Cialdini also lends us a handful of ideas to keep in mind as you craft messages and interact with a wide range of folks.

Human nature is remarkably stubborn, so appreciating what tends to motivate people and the persuasive appeals that tend to work can go a long way.

The better you understand both the client and the potential target audience, the more likely it is that your persuasive messaging will be heard, understood, and acted upon.

Media Attributions

- Butler Library © Chen, Andrew is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Cassettes © Cartist is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Framing © Madalina Enache is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Woodcock, J. (1977). An interview with Kenneth Burke, The Sewanee Review, 85(4), pp. 704-718. ↵

- Burke, K. (1969). A Rhetoric of Motives, University of California: Berkeley, 2nd ed, p. 55. ↵

- Pfau & Wan, 2009, p. 88. Marsh, 2015. ↵

- Marsh (2015) helpfully points out that Aeschylus, Isocrates and Plato all reached a similar conclusion: that persuasion is “multifaceted,” but at its best, it can “build respectful, honest relationships, particularly those that benefit the community” (p. 237). Smith (2021) also lists several examples of ethical persuasion. ↵

- Hogan (2013) p. 7. ↵

- Nichols, 1952, p. 136 in Hogan, 2013. ↵

- Zappen (2009) quoted in Hogan (2013), pp. 7-8. ↵

- Berlin, 1992, p. 20. ↵

- Leach, W. (2018). Marketing to Mindstates: The Practical Guide to Applying Behavior Design to Research and Marketing. Lioncrest Publishing: San Bernardino, CA, pp. 31-32. ↵

- Leach, ibid., pp. 74-75. ↵

- Leach, ibid., p. 63. ↵

- Leach, ibid., pp. 112-117. Also, Leach argues each motivational state is experienced through a more optimistic lens or a more cautious lens—for a total of 18 mindsets. ↵

- Leach, ibid., pp. 119-120. ↵

- Kenneth Burke. Language as Symbolic Action, University of California: Berkeley, 1966: 44. ↵

- Shen & Bigsby, in SAGE Handbook of Persuasion, 2012, p. 30. ↵

- Examples from Cialdini & Rhoads (2001), “Human Behavior and the Marketplace,” Marketing Research, 13(3). ↵

- Cady Lang, Time, November 2, 2017: https://time.com/5007964/kfc-fried-chicken-bath-bombs/ ↵

- This is a modification of Guth & Marsh’s “Purpose, Audience, Medium” concept. The reason for the slight tweak is that social media would rightly be considered a medium itself, but language choices can and should vary greatly depending on the particular platform. It's also hoped that "Method" reinforces the notion that theories are embedded in outreach efforts. ↵

- Panda, G., Upadhyay, A.K., and K. Khandelwal (2019). “Artificial intelligence: A strategic disruption in public relations,” Journal of Creative Communications, 14(3): 196-213. ↵