11 Strategic Writing

Nathan J. Rodriguez, Ph.D.

“The two words ‘information’ and ‘communication’

are often used interchangeably,

but they signify quite different things.

Information is giving out;

communication is getting through.”

—Sydney J. Harris[1]

“Vigorous writing is concise.

A sentence should contain no unnecessary words,

a paragraph no unnecessary sentences,

for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines

and a machine no unnecessary parts.”

—William Strunk, Jr.[2]

First, a Story…

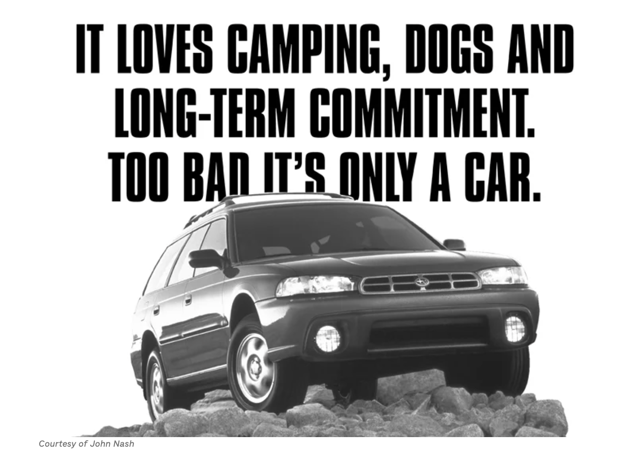

“You don’t have an image problem,” said advertising executive Willy Hopkins, during his pitch to the leaders of Subaru. “The problem is, you don’t have an image.”[3]

He was right.

Subaru had paltry sales figures compared to its competitors at Toyota, Honda, and Nissan. At this time, in the mid-1990s, the company had tasked various agencies with establishing its brand identity, ranging from larger New York firms like TBWA to smaller, innovative agencies such as Wieden+Kennedy that built a reputation from its work with Nike.

Nothing seemed to work.

The company simply couldn’t compete and capture enough of the standard 18-to-35-year-old male demographic that was so sought after by car companies. They built solid, dependable vehicles that were in no way flashy or eye-catching. Subaru was in the middle of a seven-year sales slide, and it needed a different approach or it risked going out of business.[4]

The company identified five groups that were responsible for half of all its sales: teachers and educators, health care professionals, IT professionals, outdoor enthusiasts, and lesbians.[5]

The ad agency Mulryan/Nash clicked through about a half-dozen slides in their presentation before making it clear, in their pitch to executives, that their target audience would be lesbians. This was a bold suggestion in the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” era of the mid-1990s, when very few celebrities were openly gay.[6] Indeed, when Ellen Degeneres came out as gay in an episode of her sitcom in 1997, the ensuing controversy caused a number of companies, including Chrysler, to pull ads from the show.

Mulryan/Nash recalled a moment of confusion when the Japanese executives from Subaru looked up “gay” in their dictionaries, and “nodded at the idea enthusiastically” because, after all, “Who wouldn’t want happy or joyous advertising?”[7]

After some additional clarification and persuasion, Subaru ran with the idea.

The very first ads were overt and plainly directed at the lesbian market, and they were unsuccessful. So, Subaru fine-tuned the strategy, this time using advertising approaches that were playfully coded in a way that may go unnoticed by most of the audience, but would be seen and heard differently by the gay community.[8] In essence, it was an inside joke written for the target audience.

One ad featured two Subarus side-by-side. An Outback with two mountain bikes had a rainbow bumper sticker with the license plate “CAMP OUT” and a Forrester with a kayak strapped to the top had the license plate “XENA LVR,” in reference to the Xena, Warrior Princess TV series that starred Lucy Lawless as a strong female protagonist.

The company expected some backlash, and conservative groups soon called for a boycott. Subaru believed its drivers were “diverse and well educated,” and therefore the core customers wouldn’t be offended by the messaging, and they were right. Indeed, research by their marketing team revealed that none of the people who threatened to boycott the company had ever purchased a Subaru.[9]

The ad campaign was one of the very first mainstream media campaigns to reach out to the gay and lesbian community, and it turned things around for the company.[10] Two years after the campaign, Subaru sales finally began to increase, and the company never looked back.

The Takeaway

Today, ads featuring members of the LGBTQ+ community are commonplace. But there are lessons to glean from Subaru’s choice to lean into a subset of its core audience.

To be clear, the company didn’t solely rely on the gay community. During that time period, it also tailored messages to the other four groups that drove its sales, but the gay market was one of the best for the company. Subaru proved to be ahead of its time and was the only car company to not lose market share during a subsequent recession. By the 2010s, only Tesla grew faster than Subaru.[11]

Subaru found its audience, and it spoke to that audience in a way that felt natural.

It had purposeful messaging embedded in its advertising that differentiated it from the competition.

What We’ll Cover:

Style & Terminology

The more formal the writing, the more style and formatting matter.

Various academic disciplines use different styles, among which APA style, MLA style and Chicago style are the most common. The basic idea is that you’re writing a research paper and need to find a way to “show your work” and link each claim to a source of information. APA style and MLA style both use in-text citations, while Chicago style advises the use of footnotes or endnotes. When constructing a campaign proposal, perhaps your professor, supervisor or client has a style preference. If they do, go with that, but chances are the typical recipient will be fine with any one of these as long as the basic guidelines are followed.

All public-facing writing should follow AP style. AP style references the Associated Press Stylebook that’s used for media writing. The stylebook offers specific guidance regarding a range of elements, including capitalization, spelling, and punctuation. It has more than 5,000 entries. Because the way we speak and write is constantly changing, AP Style is constantly changing.

There’s a new AP Stylebook and e-book available each spring, and there’s no substitute for it. But if you are at least familiar enough with the fundamentals of AP Style, you’re generally in good shape. Beyond that, follow AP Stylebook on social media: Its accounts provide daily reminders regarding common word use and updates on changes to previous entries. The Online Writing Lab at Purdue University is an excellent free resource.

News Releases: Overview

This section is lengthy out of necessity. As a practitioner, you’ll be expected to know how to write a great news release. At times, it may seem like a lengthy list of “do” and “do-not’s”, but for a media member to take you seriously, you need to demonstrate your familiarity with the rules of the game.

We’ll start with what constitutes a news release, then cover the content and formatting considerations for the header, headline, body and boilerplate. Finally, we’ll examine related items such as a media kit, backgrounder, fact sheet, and media alert.

News Releases: What are they?

A News Release is a publication-ready article written by an organization that is sent to specific members of the media. Unlike advertising, in which an organization pays a media outlet to run an ad, there’s no guarantee of publication, which is why it’s also referred to as a type of earned media.

News releases are written by an organization, but are balanced and neutral enough to have the appearance of being written by a media outlet. They blend in with existing content. For the past hundred years, studies consistently suggest that at least half the news articles published in independent media were sourced from, or significantly influenced by, PR practitioners.[13]

News releases are written in AP style. From the perspective of a media writer, the closer something is to being perfectly written in AP style, the better. It makes their jobs easier. When a news release deviates from proper AP style or the release is littered with grammar and usage errors; it creates more work for the recipient and makes it less likely they’ll be interested in correcting your mistakes. When in doubt, look it up. When you’re 95% sure something is correct, look it up.

Zitron’s Rules for News Releases[14]

- Don’t make it longer than 400 words.

- Don’t try to be funny.

- Proofread it at least twice.

- Target the right media

- Have something of value to share

There are a few basic types of news releases. Announcements of news and upcoming events tend to be the most common, and are written like a traditional news story. There are also feature stories that combine information and entertainment, stories that offer reactions to a situation or a local perspective on a broader trend or topic, and op-ed (opinion-editorial) columns.[15],[16],[17] Knowing the type of release you want to craft is critical to knowing where the story fits in, who to contact, and why it might be of interest to media outlets. You’ll also want to incorporate concepts from the chapters on framing, storytelling, message development, and pitching.

As a general rule, news releases are sent to individual members of the media via email. That email should include items that eliminate obstacles to publication such as links and attachments for high-resolution images and videos, as well as background information about the company and the contact person. The following section digs into additional details about constructing a news release.

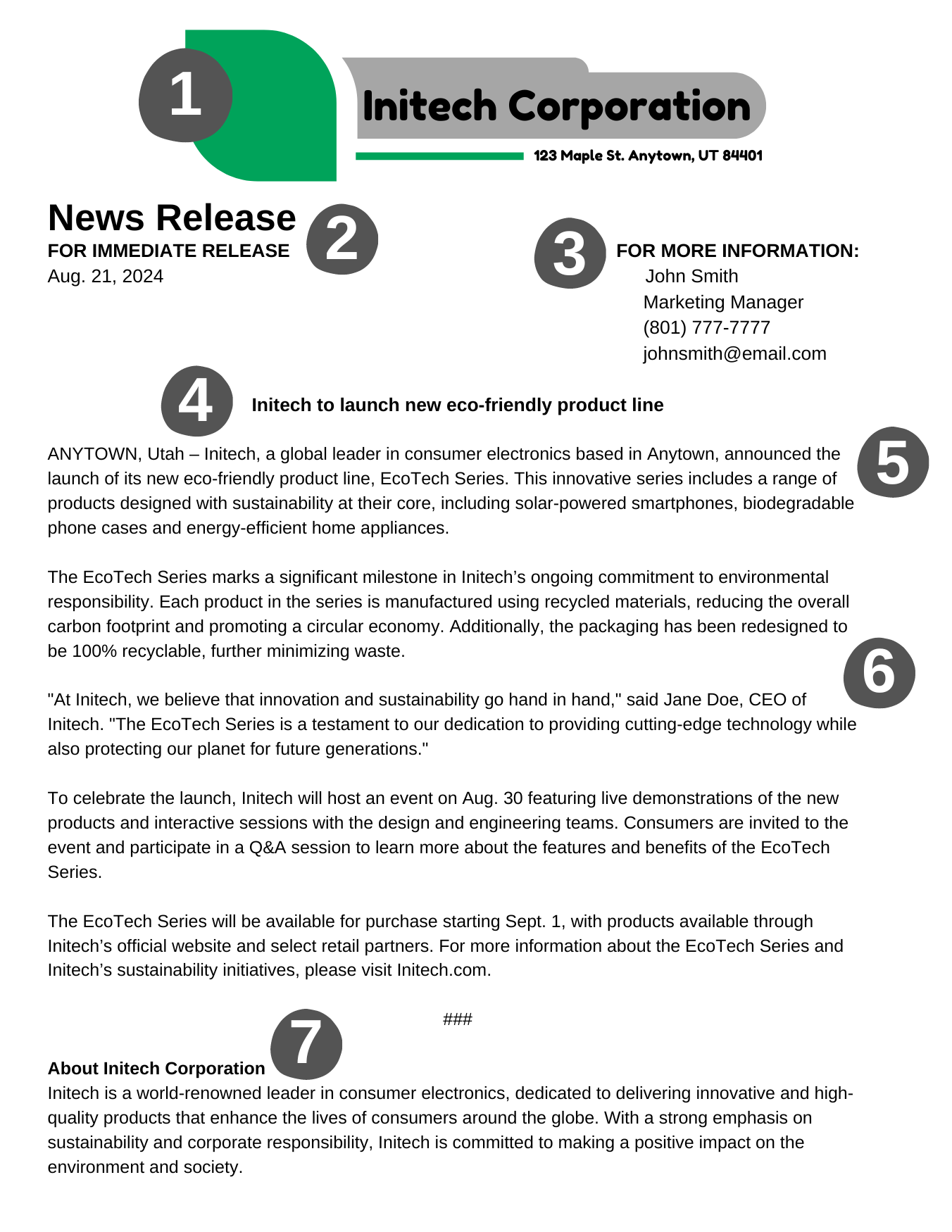

Anatomy of a News Release[18]

News releases are normally distributed via email, but not always. There are occasions where someone expects a PDF or even a paper version of a release. For example, PDF versions of news releases are commonly found on organizational websites. Your own portfolio, assuming it contains a sample news release or two, will have that in PDF form. It’s common for employers to ask finalists for a PR-related position to craft a news release.

Email knocks out some of the formatting considerations, but it’s critical to first know how to construct a news release in such a way that a seasoned professional could glance at it, and in the matter of just a few seconds, know that you understand the basics. A chef knows their dish will ultimately succeed based on taste, but they also understand the importance of presentation. The same idea regarding first impressions applies here, as folks will absolutely form snap judgments as to whether you’re the person for the job.

Because there’s a little more that goes into traditional formatting, we’ll cover that first. There is not a single agreed-upon method of laying out a news release, but here we’ll follow the guidelines first recommended by Marsh, Guth, and Short, as their method is broadly accepted, comprehensive, and visually balanced.[19] With that, it’s time for a top-to-bottom description of the key components of a news release: The content and formatting for the header, the headline and body, and boilerplate.

Sample News Release

Header (points 1-3 on the sample release)

1. Letterhead

- Center at the top of the first page

- The format varies by organization, but is typically a combination of a name, logo and address

- It only appears on the first page of the release

2a. News release

- This label allows the recipient to immediately identify the document

- Should be in Bold typeface, typically 24-point type

2b. FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE

- Appears in Bold and All-Caps, about a line break below “News Release”

- This means the release is suitable for publication upon receipt

- Some news releases are embargoed, meaning they are not to run until a certain date. This label eliminates any confusion

- If the news release is embargoed, use the phrase “UNDER EMBARGO UNTIL” followed by the embargo date, which is when the journalist may publish the story

- Some news releases are embargoed, meaning they are not to run until a certain date. This label eliminates any confusion

2c. Date

- Today’s date (follow the format used in AP Style)

- This is the date the release is being sent. It’s not related to any other dates that may be mentioned in the release.

3. FOR MORE INFORMATION:

- Bold typeface, All-Caps

- Should appear on the same line as “FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE” to lend visual balance.

- Placing contact information here rather than lower does a couple of things: It places your name in a position of prominence and also provides the recipient with all relevant information at a glance.

- Contact Information in this section should include:

- Name

- Position

- Phone

Headline & Body (points 4-6 on the sample release)

4a. Headline

- Leave an inch or so between the content of the header and the headline

- Bold and centered

- Capitalize the first word and any names (people, buildings, orgs)

- Lowercase all other words

- Content should summarize the story’s main point and local angle

- Use:

- Omit:

- Forms of the verb “to be” (is, am, are, was, were, be, being, been)

- Articles (a, an, the)

4b. Dateline

- The location that the story takes place

- It’s called a “dateline,” but no date is involved

- Establishes local interest

- Name of the city is in all-caps

- Comma between the city and state

- LAWRENCE, Kan. –

- State abbreviation follows AP style, not postal abbreviations

- AP has a list of 30 cities considered prominent enough to stand alone, and no state should be listed

- Ex: SALT LAKE CITY –

5. Lead Sentence and Paragraph

- Intent is to immediately capture someone’s interest and make them want to continue reading. Think of it as your elevator pitch.

- Establishes the main idea and sets up the rest of the story

- A good newsworthy first sentence concisely covers who, what, when, and where.

- Of these, “When” is typically the least important, so don’t sweat it if it feels like a stretch.

- The story never relies upon the headline for information or context.

- The headline is often one of the first things an editor will alter.

- Print journalists often spell it “lede,” so use that spelling when communicating with media members[22]

6. Second and third paragraphs

- Build upon the lead and transition to the paragraphs that follow

- Common to include an attention-grabbing quote from a key figure

- Supporting facts that emphasize the news

Inverted Pyramid

The most common way to construct a news story is to follow a structure known as the inverted pyramid. Start with the most important information, expand on it, and then arrange the rest of the story in descending importance.[23]

This style is not without its disadvantages,[24] but this is a case where it’s better to learn the rules before you break them. In other words, learn how to construct a story in the traditional way before deviating from the formula.

The lead sentence (and opening paragraph) establishes the most newsworthy information and answers who, what, when, where, and why.

The next paragraph amplifies the lead and provides a transition to the paragraphs that follow. It’s common to include quotes from key figures and supporting facts that emphasize the news in the second and third paragraphs.

From there, include additional quotes and information in descending importance, meaning that background, general information, and minor details appear last.

This doesn’t mean the story just fizzles out toward the end. Rather, it’s an opportunity to circle back to an established theme, provide a representative anecdote that ties back to the lead, or offer a statistic that’s relevant to a key point. As one journalist put it, “Want to write well? Open with a punch, close with a kick.”[25]

Content: Quotes and Transitions

- Quotes

- Good quotes provide color, emotion, and/or opinion

- They make the story lively.

- Readers find them interesting.

- They make the story believable.

- Reliable sources are speaking in their own words in the story.

- Quotes are not always required

- Sometimes if the release is just a brief blurb, a quote is not necessary or expected.

- It’s better to omit a weak quote than include it.

- Self-praise, stating the obvious, or reporting statistics are all low-quality quotes.

- Three Basic Types

- Direct quotes

- The best direct quotes are short and emotional.

- Use a direct quote when someone says something important, colorful or controversial,

- Allow the source to speak directly to the reader through the quote to reveal their character or when you can’t improve the information through other means.

- Indirect quotes

- Use when sources don’t state ideas effectively.

- Rephrase the quotes for clarity.

- Writers can combine ideas from several direct quotes into an indirect quote.

- Partial quotes

- Partial quotes are one solution to a weak/confusing quote, but it’s not an ideal way to write. Partial quotes can be awkward and distracting.

- Avoid “orphan quotes” that place quotation marks around one to two words that were used in an ordinary way. This can imply an unusual or sarcastic delivery.

- Direct quotes

- Final Tips for Quotes

- Summarize a major point immediately prior to a direct quote.

- The quote then provides new information that enhances that summary. It should not repeat facts.

- The default attribution is “X said” not “said X” or “says” (TV and radio use present tense; print and online use past tense.)

- Always use “double-quote marks” rather than ‘single-quote marks.’ The only two exceptions are headlines and quotes within quotes.

- If a quote is good but lengthy, split it and place the attribution in the middle.

- Less experienced writers commonly struggle with placing quotes in a way that doesn’t sound clunky.

- The best way to improve is to review published articles. Notice how they set up the quote and how the quote pushes the story further. Study how the quote is structured, including the placement of attribution as well as punctuation.

- Unlike traditional journalism, PR and Strategic Communication practitioners can craft a quote and attribute it to another person at the organization (after getting their approval).

- Summarize a major point immediately prior to a direct quote.

- Transitions help the story move from one fact to the next in a way that’s smooth and logical. If our story is a train, transitions are “the couplings that hold the cars together.”[26]

Final Formatting

- The body should be single-spaced, with line breaks (and no indents) between paragraphs.

- If the release exceeds one page:

- type -more- or -over- centered at the bottom of the page;

- on all pages after page one, in the upper-right corner, provide the slug and page number. The slug is a condensed version of the headline, typed in all-caps.[27]

- After the last line of content in the release:

- add one more line break; then, centered at the bottom of the document, type either -30- or ### or END to signify the end of the release.[28]

Boilerplate (point 7 on the sample release)

- Boilerplate is standardized so an organization uses the same copy with every news release.

- Take time to make sure it’s written well and highlights the organization.

- Boilerplate should be a brief paragraph, no more than 100 words and is placed below the -30- or ### or END.

- It’s essentially an “about us” for the journalist that provides background on the company.

- It’s tempting to include company info in the release itself, but that can be viewed as overly promotional.

- It’s common practice to include products, services, clients, awards, vision, call to action, SEO friendly keywords, link to a website/landing page.

- For more, see examples in releases submitted to the AP and Business Wire.

Email News Releases[29]

News releases sent via email are similar to traditional releases in most ways. They differ in other ways. In crafting an email news release:

- The subject line is a brief variant of the headline and should be concise, precise, and relevant to the media writer’s audience.

- Everything in the body is left-adjusted and single-spaced

- First line: “For Immediate Release”

- Second line: Date of the release

- Add a line break, then the headline

- The “For More Information” section is at the bottom of the release, after the story and boilerplate

- It is common to include: subscribe and unsubscribe links, as well as thumbnails that link to social media profiles.

Related Items

There are a handful of deliverables that are related to, and often included alongside news releases. These include media kits, fact sheets, media alerts, backgrounders, and story pitches.

- Media Kit

- A media kit should include everything a journalist may need to write a story about the organization.

- Commonly includes:

- high-resolution photos of the management team,

- photos and videos of the company office(s),

- photos and videos of people working,

- photos and videos of the product/service,

- photos and videos of events.

- For more details & examples, see this post from the Pr.co blog

- Fact Sheet

- Sometimes, but not always labeled “Fact Sheet” at the top,

- outline of who, what, when, where, why, and how,

- bold headers and a brief paragraph on each,

- ends with boilerplate (summary paragraph on the organization).

- Media Alert (a.k.a. Media Advisory)

- concise,

- labeled as “Media Alert” and includes a headline,

- similar to a fact sheet and covers who, what, when, where, why and how,

- difference is time-sensitive: There’s no time to write a full story, so the alert is to notify media members to attend (who may also inform their readers, viewers and/or listeners).

- Media sometimes used to follow up on a release. For example, an initial release may have indicated that a prominent politician was taking interest in a local problem and would visit the area. A media alert might be sent to provide information when the politician will be available for interviews.

- They can be tempting to overuse, so limit usage to breaking news and significant upcoming events, as well as events that require media credentials.

- Backgrounder

- The “story behind the story”

- How did this issue arise?

- Why did this event become notable?

- Where did the company come from?

- Backgrounders offer history for a journalist to use and also summarizes the current situation. The intent is to allow a media writer to develop a deeper story.

- The “story behind the story”

- Story Pitches

- In this instance, you’re pitching an idea for a story to a specific member of the media. The story angle is tailored to them, for their specific media outlet. It’s common to list potential interviewees and other sources of information, as well as contact information.

- Pitches that are not one-on-one are commonly viewed as spam.

- A 2024 study revealed that only about 3% of all pitches for coverage receive a response (and that 3% includes “No” responses as well)[30]

Block Format is the most common layout used in business writing, which includes everything from cover letters to memorandums and formal letters to business partners and associates.[31] All writing is left-adjusted and single-spaced, with double spaces between paragraphs.[32]

Speechwriting

Public Relations and Strategic Communication practitioners are often asked to help craft speeches for organizational leaders.

When writing a speech:

- consider the goal, purpose, and the audience,

- 20 minutes or less is standard,

- write with their voice in mind.

- Situations vary:

- They may provide certain phrases, talking points, or areas they’d like to cover, or leave it entirely to you.

- They may want to deliver a speech where each word is written out in advance, or they may prefer a rough outline with bullet points and sentence fragments.

- Double- or triple-space the document using a large serif typeface.

- Include clearly labeled cues for the speaker such as “pause for emphasis” either highlighted or noted in the margins. Be certain they are obvious enough to avoid a situation where the speaker accidentally reads them aloud.

Follow best practices for speeches with particular attention to the opening and closing remarks.

Social Media

Tips for effective communication on social media are scattered throughout the text.

There’s a delicate balance between blending in and standing out, so choose wisely. Remember the difference between building bonfires and shooting off bottle rockets.

To establish and maintain a robust social media presence, it’s helpful to consider what Karen Freberg calls the “six C’s of effective writing for social media.”[33]

- Content

- create, curate, and feature relevant content and monitor effectiveness

- should be something you and your audience is passionate about

- copy should be an appropriate fit for the target audience

- need an understanding of different social media platforms and what works best on each

- Community

- people come together around common values and interests

- Know how you fit in

- understand what people want: Do they even want content? Do they want to engage with it, or just view it?

- people come together around common values and interests

- Culture

- related to community, but related more to enduring practices and behaviors and experiences

- What’s the appropriate or expected etiquette for how people interact with one another?

- What are the long-standing debates or issues of significance?

- Conversation

- People don’t want to be advertised to all the time, and tune out when a brand pushes its messaging too hard.

- Conversation is more than just replying to a post. It’s an attempt to have a discussion that’s meaningful for both parties, as well as those who view the public interaction.

- You need to understand the appropriate tone, voice, and writing style.

- Creativity

- relates not just to content creation, but real-time conversations with the audience

- monitoring and listening can lead to better ideas and more effective communication

- Connection

- In a sense, this is the end goal to keep in mind. When the other C’s are aligned, you’re able to generate a sense of connection.

Writing Styles for Social Media[34]

Different brands use different communication styles across social media platforms, and they do so strategically.

Below is a quick list of writing styles and the brands that use them:

- Professional (General Motors)

- Snarky and Spunky (Wendy’s)

- Product- and Brand-Focused (Under Armour)

- Audience-Focused (Budweiser)

- Inspirational (adidas)

- Conversational (Dunkin’)

- Witty (Taco Bell)

- Educational (Sephora)

- Personality Focused (Charmin)

Having a style and sticking to it helps carve out an organization’s identity in online spaces.

AI Prompt Engineering

Generative AI is constantly evolving and improving. One rule of GAI tools like ChatGPT is “garbage in, garbage out,” whereby a simple prompt is answered in a simple fashion. Providing context allows the user to “push the AI to a more interesting corner of its knowledge, resulting in…more unique answers that might better fit your questions.”[35]

There are two ways of interacting with GAI: conversational prompts and structured prompts. With conversational prompts, the user interacts with GAI as though it were a human helping with a task. This is a good approach for someone new to GAI or new to a topic, and who is interested in exploring a bit

Structured prompts are more purposive in nature. It’s been suggested that the need for structured prompting is a temporary issue that may be an unnecessary skill as AI improves, but at present, it helps.

There is some emerging alignment as to what constitutes a quality prompt, with some breaking it into four basic steps of “role, task, background and action.”[36] A more comprehensive template suggests five basic categories[37]:

1. Role and goal:

a. tell AI who it is and how it should behave

2. Step-by-step instructions:

a. use simple and direct language that would be easy for someone to understand who may be unfamiliar with your specific area or request

b. break the problem down into individual steps, and clearly identify different parts of the process

c. If GAI is having issues following the steps, revise as needed

3. Expertise:

a. determine what you want GAI to do and how that differs from a default response.

b. indicate if the GAI should adopt a specific viewpoint or perspective.

4. Constraints:

a. Constraints refer to rules that guide GAI behavior with the user, such as limiting the output to a certain number of words

b. It may also be helpful to consider constraints in a broader context, and identify any obstacles or objections you’d like GAI to consider in formulating a response.

5. Personalization:

a. put GAI in the role of a guide, and ask it to ask you questions; that will lead to better prompts

b. work with GAI through a series of questions gives it context to help you, as it adapts to your specific scenario

GAI is a tool to reach a solution, not the solution itself. For strategic writing, it may be used for tasks including brainstorming, editing, and summarizing materials, creating copy and content, drafting speeches, and developing keywords for search engine optimization.[38]

It’s helpful to provide GAI with examples and request specific output. That output from GAI should be a starting point, not the end point. Ask follow-up questions to refine the results, and never accept the results at face value: review it, build upon it, and humanize it.

Experts Talk Back:

Three Questions with Tegan Griffith, Public Information Officer at USDA Rural Development, Wisconsin.

Q: So, you work for the USDA office in Wisconsin, and focus on rural development. What exactly do you do for them?

It depends. The career field can kind of be generalized a bit. For this job, I work for former [State] Sen. Julie Lassa; she’s my boss. So when an entity gets a grant or loan or something from the federal government, through our programming, we’ll go and do the whole dog-and-pony show.

I’ll give you an example.

My first event was with Habitat for Humanity. We went and visited a small town in rural Wisconsin, took a tour of all the floors of this house and learned about her story. We had some VIPs from Washington, D.C., come out, and it was just kind of like a tour for people and businesses who have gotten our grants.

A lot of it is taking Julie to these businesses, homeowners, you name it. There’s a lot of panels. For me, it’s preparing PowerPoints, taking photos, organizing all the stuff once everything is over, Tweeting, press releases, event planning, graphic design. It’s a little bit of everything. (Laughs) It’s a lot…[39] We have over 50 programs just in our rural development, which is ridiculous. A lot of what I do is front-end stuff.

For example, we have a really big program called our Reconnect Program for rural high-speed internet. Applications open August 1, so we’re planning backwards for press releases and other big things like that. Washington, D.C., our national office, gives us a whole kit with talking points and slides and stuff like that, so we don’t have to do it all. But once they give that to us, a lot of it is slipping it into a slideshow, writing op-eds for the state director, and getting it out ahead of time.

We have to do a lot of stakeholder outreach, like our economic development groups and chambers of commerce. So we send that out as much as we can with approved messaging that the White House has cleared. But yeah, we’ve got to reach everybody, so in Wisconsin, we have tribal outreach; we have minority outreach; our chambers. And so we just really kind of blast everybody with a firehose, in a variety of ways leading right up to it.

You don’t want to find yourself, especially in the government, you don’t want to find yourself in a position where you’re like “well, we told you guys about this,” or there’s a community that’s really trying, and they applied to receive money but they didn’t know how, or they didn’t know about it. And I take that super personally. So, we do the best that we can with what we have.

Q: So with the whole dog-and-pony show, I’m curious: How much of it is storytelling and finding the angle you want to present to the public in terms of how the money is used and how people and organizations benefit? How much digging do you do or is there a formula for how you present the story to the public?

So for me personally, we have a programs specialist and a database with the federal government, and they’ll be able to pull me some information so I can pull the statistics, the description, and which legislative district it’s in. We have some core “meat and potatoes,” but sometimes that stuff is boring and nobody cares about that on [the social media platform formerly known as] Twitter.

My approach has been that every time we go somewhere, I record audio on my phone because the first time we went out it was so cold outside, I couldn’t keep up with typing my notes on my phone. I wound up with a good audio device I can plug into my phone and record it so I can go back and catch a quote, or just jot down the timestamp like, “Oh, this is really good.”

We had Single Family Housing Month in June, and that’s where we want to highlight the stories about the people that have taken advantage of our Single Family Housing Loan Program.

So, I wrote a story about this woman, who, her and her family and her four kids were living in a two-bedroom apartment, and worked with Habitat for Humanity, put in some sweat equity, and built a house. And management and upper-level types are there doing the whole “kissing babies and shaking hands” thing, and I tend to be off to the side listening for little stories. So the way I wrote her story—her kids are special needs, but you can’t exactly say that—you want to protect her privacy, because we’re out nationally. And so her kids have special needs. Well, they were having a problem with six people being in a two-bedroom apartment for a couple of years. And their kids couldn’t jump up and down when they were excited. They had to be quiet because they were in an apartment all the time. And she told this story about how “now that our kids get excited, they can express themselves,” and they have their own bedrooms, so their kids can grow and learn and be themselves in this house, in this safe environment without having to worry about making somebody angry.

The way she talked about it, she just lit up because it was about her kids. So that’s kind of how I framed the story. I took her off to the side. I took pictures with just her and me while everybody was leaving, backing their bags. I stayed back with her and just made sure, because sometimes people don’t want to tell their stories, or they’re nervous about how you tell their stories, especially when it’s something like this.

So I tend to look for the more important smaller things that everybody else may be overlooking. Our VIPs kind of made it a thing where they’re like “well, you’re Latina, or you’re this, and your kids are that”—totally putting them into silos. And that family now has a really nice house with a roof over their head, and the kids can be themselves and have a backyard to play in. That’s the human decency story that I would prefer to tell over saying “you’re this, this, and this, and this is how we help you,” because after a while it starts to feel really run-of-the-mill and government-y.

A lot of it was her story that I told. We also talked about our partnerships with Habitat for Humanity, and the town, and the economic development group, and volunteers, but the story wasn’t about them. The story is about her and her kids, and that was the end of the story. So that was really good. I got some gold stars on my homework for writing that, and it was very rewarding because I know that I told her story with confidence, and she didn’t have to worry about me putting her in some kind of silo or making her feel bad about her situation

Q: That’s awesome. I’m glad that it’s been a meaningful job and one that brings joy to you to be able to write that story in the first place—I’m so happy for you. So last question: What advice would you have for folks who are just on the verge of entering the workforce?

It’s not about social media 100% of the time. You still have to know how to write well, because you’re writing tweets, you’re writing press releases and speeches. There’s a lot of interpersonal skills. We have 50 people in our office here, and they range from just on the edge of retirement to 15 years younger than me…[40]

So, for students, you might have to do a little groundwork before you’re handed the reins to an organization. They’re not just going to give you the social media accounts on the first day—with the government at least. Agencies and other groups may be different…

Professor [Jim] Haney passed away earlier this year, but he said something—and I was so bummed when he retired—but he said something, and I’ll paraphrase it here. He told our class if you want to stay relevant in this field, you have to look to the younger generations of people that are in college, and the people and practitioners that are coming up behind you because they’re going to be the ones who know how to access their peer group and access current technology that you either haven’t had an opportunity to be trained on, or you don’t know about it, or haven’t had the time to learn about it.

So, you have the folks ahead of you who can give you those hard skills—writing, interviewing, stuff like that—but then the ones behind you, you’ve got to keep them in your good graces. They’ll teach you how to use Snapchat for your organization. Maybe that’s something you want to get off your plate. Or if some manager says “I want to be on TikTok,” well, there’s like six of you that can help us figure that out.

So, it’s not really about the individual. It’s about who you work for, who you represent, and the people you serve. And then just keep in mind that the people coming up behind you are going to be able to help you out at some point.

Tips and Tricks

There are a handful of principles to keep in mind with any strategic writing.

- Stay on message.

- All communication is on-message or off-message.

- Beware the curse of knowledge[41]

- The danger of expertise in an area is that it becomes difficult after learning something to remember what it was like to not know a concept or bit of information. There’s a tendency to assume others understand our words, and share our skills and knowledge.

- In communicating with other experts, this tends to matter less. But even then, areas of expertise don’t always neatly overlap. In virtually every other instance, though, shed the jargon to connect.

Tactical Tip: Group Writing & MACJ

Harvard Business Review contends the writing process has four phases, each of which correspond to different parts of our brain: Madman, Architect, Carpenter, and Judge.[42]

In the madman phase, research and find out as much information as you can. In the architect phase, organize that information in a rough outline in a way that’s strategic and makes sense. In the carpenter phase, craft sentences and paragraphs using the outline provided by the architect. In the judge phase, focus on overall quality control, including polishing the line-by-line phrasing, and correcting issues related to grammar and flow.

This process may be helpful as you craft any document.

It may also help with a group paper, as it can lend a sense as to how you could choose to divide the labor in a way that plays to the strengths of the group. Here, even though one person may take on the bulk of the responsibility for a particular phase, it’s advisable for everyone to remain involved from start to finish. As the writing process moves forward, you may find that you need to revisit a previous phase to strengthen the final product.

- The singular is more powerful than the plural.

- Dubbed “The Mother Teresa Principle,” it echoes her observation that “If I look at the mass, I will never act. If I look at the one, I will.”[43]

- The most successful mass communication is that which most closely approximates personal communication.[44]

- “Each of you” is better than “All of you” or “everyone”

- End the sentence with a strong word.

- Just as you want to end the joke with a punchline, and not continue to talk beyond that, end the sentence on a high note.

- Vary sentence length

- Vary the length of sentences to improve the flow of your writing. It’s easy to have quite a few back-to-back sentences that are of a similar length. Mix it up! Shorter sentences pop, give the reader a break, and allow you to expand upon other ideas in greater detail.

- This theory was perhaps best expressed by Gary Provost, in his work: “This sentence has five words.” It’ll only take a minute to read. Check it out.

Summary: Putting it All Together

Regardless of how complex a situation may be, we can always return to the three factors mentioned in Chapter 6: Purpose, Audience, and Method. Identifying what you want to accomplish, who you want to reach, and how you’re trying to reach them will help determine the content and style of the messaging.

That strategic approach should also be informed by key concepts regarding interpersonal communication, persuasion, and storytelling. Knowing how and when to deploy those concepts is like knowing how and when to use certain tools in a toolbox: They’ll help you get the job done.

Media Attributions

- Subaru ad

- Sample news release © Alexis Kiedaisch is licensed under a CC BY-ND (Attribution NoDerivatives) license

- Tabet, M. (2020, March 9). “Distinguishing between your ‘what’ and ‘why’ can greatly impact your brand,” Forbes Communication Council. Retrieved from: https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbescommunicationscouncil/2020/03/09/distinguishing-between-your-what-and-why-can-greatly-impact-your-brand/?sh=70ec301719a9 ↵

- Strunk, W., & White, E. B. 1. (2000). The elements of style. 4th ed. New York, Longman. (Pages xv-xvi). ↵

- Rothenberg, R. (1994). Where the Suckers Moon: An Advertising Story. Alfred A. Knopf: New York. (Page 144). Emphasis added. ↵

- “Episode 729: When Subaru Came Out,” (2016, Oct. 14). Planet Money [Podcast]. Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2016/10/14/497958151/episode-729-when-subaru-came-out ↵

- Mayyasi, A. (2016, June 22). “How Subarus came to be targeted to lesbian drivers,” The Atlantic. ↵

- Mayyasi, Ibid. ↵

- Dicker, R. (2012, June 18). “Tim Bennett, John Nash call for a unified Gay Pride holiday, new marketing strategy,” HuffPost. Retrieved from: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/tim-bennett-john-nash-gay-pride-advertising_n_1591457 ↵

- “When Subaru Came Out,” Ibid. ↵

- Mayyasi, Ibid. ↵

- IKEA is widely viewed as the first company to target the LGBTQ community, and it received bomb threats for doing so. Volkswagen also ran a very subtle campaign prior to Subaru, but played coy rather than acknowledging it outright, while Subaru unapologetically embraced the approach and began to openly support the community in other ways outside of the campaign. ↵

- Mayyasi, Ibid. ↵

- Just seeing if you were paying attention. ↵

- This study showed up to 75% of content in independent media is sourced from/influenced by PR, while also highlighting a 1930s study that showed more than 60% of stories in one newspaper came from PR, as well as a 1970s study showing 75% of articles in The New York Times and Washington Post were characterized more as “information processing” rather than reporting. A 2006 survey of 400+ journalists estimated 44% of all content was the result of PR contact. Data from: Macnamara, J. (2014). “Journalism-PR relations revisited: The good news, the bad news, and insights into tomorrow’s news,” Public Relations Review. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.pubrev.2014.07.002 ↵

- Zitron, E. (2013). This is How You Pitch: How to Kick Ass in your First Years of PR, Sunflower Press: Muskegan, MI. Pages 95-96. ↵

- Filak, V.F. (2016). Dynamics of Media Writing: Adapt and Connect. Sage: Los Angeles. ↵

- Page, J.T. & Parnell, L.J. (2019). Introduction to Strategic Public Relations: Digital, Global, and Socially Responsible Communication, SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA. ↵

- Hendershot, A., Loewen, L., Marsh, C., Guth, D.W., & B.P. Short (2024). Strategic Writing: Multimedia Writing for Public Relations, Advertising and More, (6th ed.), Routledge: New York. ↵

- Content from this section primarily comes from lectures by David Guth, the Hendershot et. al (2024) text, and Bender, J.R., Davenport, L.D., Drager, M.W., & F. Fedler (2019). Writing and Reporting for the Media (12th ed.)., Oxford University Press: New York. Several of these bullet points were added to my own lectures years ago, and I did not always track the original source of information. In my experience, there is substantial overlap in the recommendations, but I’ll readily acknowledge that these bullet points are woven together from fabric produced by other folks. ↵

- Note: The Hendershot et. al., (2024) citation is the most recent edition of the text, and it’s used as the primary point of reference here, but the section on News Releases is essentially unchanged from earlier editions by those three authors. ↵

- The body is written in past tense, but headlines are different! ↵

- The body will use “double-quote marks,” but headlines are different! ↵

- The rationale for the alternate spelling is to differentiate “lead” as in the beginning of an article from the lead that was commonly used in the printing press. Times change, but a good journalist will notice that you’re “speaking their language.” ↵

- For years, journalism textbooks attributed the development of the Inverted Pyramid Style to the telegraph. As the story goes, journalists previously had the luxury of writing stories as richly detailed narratives and then sending them as letters. The telegraph brought about the ability to transmit information at an instant, but transmissions were relatively expensive and not always reliable—the line may be lost—so the most important information was placed first. More recent studies show that widespread adoption of the Inverted Pyramid style didn’t come about for several more decades, and it was only after the first journalism schools were established that the science of writing stories evolved, and the inverted pyramid was accepted as the standard. For more, see: Errico, M., April, J., Asch, A., Khalfani, L., Smith, M.A. & X.R. Ybarra (1997). “The evolution of the summary news lead,” Media History Monographs, 1(1): 1-19. Those basic findings were echoed in Poynter: Scanlan, C. (June 20, 2003). “Birth of the inverted pyramid: A child of technology, commerce and history,” Poynter. Retrieved online at https://www.poynter.org/reporting-editing/2003/birth-of-the-inverted-pyramid-a-child-of-technology-commerce-and-history/ ↵

- Some facts may be repeated later in the body; there are no real surprises, since the lead reveals major facts; it locks the writer into a formula; it’s overused. See Bender, J.R., Davenport, L.D., Drager, M.W., & F. Fedler (2019). Writing and Reporting for the Media (12th ed.)., Oxford University Press: New York. Pages 180-181. ↵

- Bender, J.R., Davenport, L.D., Drager, M.W., & F. Fedler (Ibid.). Page 186. ↵

- Bender, J.R., Davenport, L.D., Drager, M.W., & F. Fedler (Ibid.). Page 197. ↵

- Slug is another term that comes from the typesetting days where a line of lead was known as a slug. ↵

- These also date back to the telegraph: “30” was the Western Union code to signal the end of the document. Also, in a telegraph, “X” was used to mark the end of a sentence, “XX” signified the end of a paragraph, and “XXX” ended the transmission. ↵

- Hendershot et. al., (2024), Ibid. ↵

- Carter, A. (Jan. 19, 2024). “By the numbers: This is how many pitches actually get responses,” PR Daily. Retrieved from: https://www.prdaily.com/by-the-numbers-this-is-how-many-pitches-actually-get-responses/ ↵

- “Writing the basic business letter,” (n.d.). Purdue Online Writing Lab. Retrieved from: https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/subject_specific_writing/professional_technical_writing/basic_business_letters/index.html ↵

- A general rule across Styles is that paragraphs are either indented with no space between them, or not indented with a double-space between them. Block Style uses the latter. ↵

- Freberg, K. (2019). Social Media for Strategic Communication: Creative Strategies and Research-Based Applications, SAGE: Thousand Oaks, CA. ↵

- Freberg (2019) Ibid. ↵

- Mollick, E. (2023, Nov. 1). “Working with AI: Two paths to prompting,” One Useful Thing, Retrieved from: https://www.oneusefulthing.org/p/working-with-ai-two-paths-to-prompting ↵

- Penn, C. (2023). The woefully incomplete book of generative AI. Trust Insights. ↵

- Mollick (2023), Ibid. ↵

- McCorkindale, T. (Feb. 7, 2024). “Generative AI in organizations: Insights and strategies from communication leaders,” Institute for Public Relations. Retrieved from: https://instituteforpr.org/ipr-generative-ai-organizations-2024/ ↵

- Note: A brief follow-up question regarding “front-end” preparation was omitted here in favor of ellipses, and her answer to both questions is presented in full here. ↵

- Middle portion of the response is omitted here. Then, after the “Agencies and other groups may be different” reply, her final summarizing statement is included, as it built upon her advice to current students. ↵

- Heath, C., & Heath, D. (2007). Made to stick: Why some ideas survive and others die. New York: Random House. ↵

- Garner, B. (2013). HBR Guide to Better Business Writing. Harvard Business Review Press: Boston. Author’s Note: I wish the first phase had a different moniker, but present it here as the author did. ↵

- Heath & Heath (2007), Ibid. ↵

- Attributed to David D. Perlmutter, as noted in a previous chapter. ↵