8 Social Media, Influencers & Analytics

Nathan J. Rodriguez, Ph.D.

“I propose to consider the question: ‘Can machines think?’”

—Alan Turing, 1950[1]

“The internet…Is that thing still around?”

—Homer J. Simpson, 1999[2]

First, a Story…

It was Sept. 25, 2020, in the middle of the pandemic, before the COVID-19 vaccines were developed, and just a few weeks away from the presidential election. In a broad sense, people were exhausted.

Nathan Apodaca lived in a trailer in Idaho Falls with inconsistent electricity and no running water. Just before 8 a.m., he climbed in his 2005 Dodge Durango that had logged more than 300,000 miles, and made his way to work at a potato warehouse, where he’d worked for more than 13 years.

Less than two miles away from work, his Durango dies. This isn’t a surprise, as it happens frequently enough that Apodaca has a longboard with him. Timewise, he is cutting it close, so instead of waiting for someone to give him a ride, he grabs his longboard.

Apodaca also grabs his phone and something to drink. Moments later, he’s gliding down the shoulder of a highway. He films a short clip of him taking a swig from a jug of Ocean Spray Cran-Raspberry Juice as “Dreams” by Fleetwood Mac plays in the background. A few seconds later, he turns to face the camera and lip-syncs the Stevie Nicks line, “It’s only right that you should play it the way you feel it.”

He uploaded the 25-second clip to TikTok, and considered deleting it. Or, as he later put it, “If they ain’t feeling the vibe, I’ll just pull it. No harm, no foul.”[3]

It struck a chord. Within an hour, the free-spirited video had been viewed more than 100,000 times.[4] Within a couple of days, it had tens of millions of views. As one observer of popular culture put it, “Apodaca, vibing so hard and balancing such a precarious situation (the juice, the skateboard, life) so effortlessly, almost seems to emanate a Buddha-like energy in the video.”[5] It was the right video at the right time.

Our story has a happy ending. Ocean Spray surprised him with a new cranberry-colored truck, loaded with dozens of bottles of Ocean Spray Cran-Raspberry Juice. Donations came pouring in from other directions, and he received more than $400,000—allowing him to pay for a new home in cash.[6] He partnered with a range of companies, guest-starred in FX’s “Reservation Dogs,” and launched his own line of merch.

The Takeaway

Apodaca’s life was forever changed by those 25 seconds. At the time, his video generated substantial attention for Ocean Spray and Fleetwood Mac, and brought about similar tribute videos by celebrities, CEOs, and politicians.

Today, it’s a good example of fleeting ubiquity on social media.

If you asked someone about the video now, chances are they may vaguely remember it—perhaps recalling the skateboarding, but maybe not his choice of song and drink. Apodaca, a.k.a. @doggface208, still creates content on TikTok, and now has more than 2 million followers, but most of his videos tend to garner around a thousand views. The rest of the world moved on.

Social media ages in dog years (or doggface years. Sorry). What’s innovative one week or month might be old news the next. Latching on to the latest trend can work when a range of factors align, but over the long term for most organizations, that approach will be unsustainable and unmemorable. For that reason, it’s worth developing a long-term strategy.

Introduction to Social Media & Analytics

If someone were asked to describe a telephone and how to use it, there would be very different responses in 1960, 1990, and 2020.[7] A similar question might be posed regarding social media in 2005, 2010, 2015, and 2020—and it would also be followed by very different responses.

Social platforms come and go with user preferences. Platforms that stick around have staying power because they capture people’s attention and time. Brands that experience success online have a healthy understanding of the culture and find ways to make themselves useful.

There can and should be an emphasis on analytics—of tracking clicks, reach, and engagement.

But first things first: It’s critical to first determine what you hope to achieve and how you’ll do it. Otherwise, you may be left with a deep knowledge of analytics, but without a vision of how to generate better numbers.

In this chapter, we’ll review a handful of principles to guide an effective approach to social media, and then briefly examine ways to think about analytics.

What We’ll Cover:

Online Culture

Some core characteristics of social media are that it is peer-to-peer, participatory, conversational, and relationship-oriented.[8] Of course, the list of potential descriptors is much longer, but let’s start there.

Rather than a single media outlet broadcasting messages to an audience, the lines between producers and consumers of content have blurred, as users generate content.[9]

If we return briefly to the idea of uses and gratifications theory, when someone opens an app for social media, they expect to feel and achieve something from the action. Perhaps they want to create and share content with others. Maybe they are casually scrolling to pass the time. Or maybe they are doing something in between: By reacting to and interacting with content, users co-create meaning. And of course, a user may occupy each of these roles in different ways at different times.

As incongruent with reality as it may seem, the Golden Rule of treating others the way you’d want to be treated can help us understand how social media functions. Brands must begin by thinking of social as part of a long-term strategy to build relationships, not as a digital corral to capture attention for a fleeting moment.

Fans & Parasocial Relationships

Taylor Swift. Cristiano Ronaldo. Selena Gomez. Dwayne Johnson. Justin Bieber.

Chances are, you haven’t personally met any of the five people mentioned above, but you probably have an opinion about them. The same is probably true of many of your most and least favorite online personalities.

One quick way to categorize someone’s relationship to a mediated figure or brand is that they are a fan—short for “fanatic.” There are also anti-fans, who don’t like a media persona, brand, or “text.”[10] And then there are non-fans that might be aware of a persona, brand, or text, but don’t hold any particularly strong feelings one way or the other.[11] These categorizations are not rigid. People frequently change their opinions of other people, brands, movies and sports teams. Instead, use these categories as a way to think about how to enhance those relationships.

In the mid-20th century, researchers noticed that people developed an affinity and/or antipathy toward “mediated” figures in movies, radio, and television. The term Parasocial Interaction describes this “seeming face-to-face relationship between spectator and performer” as the media personae become “integrated into the routines of daily life.”[12] Parasocial interactions are situationally bound and occur while we watch, listen, and scroll. Over time, these feelings develop into Parasocial Relationships, which occur over the long-term and are more enduring.[13]

After these initial observations regarding PSI and PSR were made and proven time and again through subsequent studies, researchers moved on. Then along came social media, which breathed new life into the concepts.[14]

Some key takeaways from more than 60 years of research are refreshingly straightforward. For decades, there has been a near-consensus that PSI mirrors social relationships in that people tend to use similar methods of evaluating media personae as they do in social relationships.[15],[16] People even consider their favorite media figures more favorably than good neighbors.[17] In other words, many of the concepts discussed in Chapter 4 regarding relationships dovetail neatly with best practices online.

Building Parasocial Relationships

Building parasocial relationships, as with in-person relationships, hinges on prioritizing an outward mindset (see Chapter 4), and seeing people as people. As such, people expect brands to be good corporate citizens in both the local and online communities. Brands that are viewed as adept at social are those that seem to be an authentic extension of the organization. They are perceived as transparent and genuinely interested in the welfare and opinions of their audience. Unfortunately, the focus of most organizations remains on the organization—often at the expense of prioritizing external stakeholders and publics.[18]

Engagement is a buzzword that can have different meanings based on the platform and the person using the term—and that’s fine. Different types of investigation sometimes require “separate and even contradictory definitions,” so definitions are just “tools that should be used flexibly.”[19] Here, we’ll define engagement as “togetherness that has a future” through ongoing and sustaining relationships.[20] There are, of course, more precise meanings with respect to analytics that we’ll get to later, but if the goal is engagement, then “togetherness that has a future” is a good way to think of it.

Dialogue is a closely related concept to engagement. In a basic sense, dialogue may simply be two-way communication—but that limited view is more properly characterized as D-I-N-O, or Dialogue in Name Only.[21] True dialogue is ethically centered in nature, with “high levels of…honest, empathetic, inclusive, and trustworthy communication.”[22] It adopts ideals from interpersonal communication and treats people with kindness and positive regard. This view of dialogue in public relations empowers practitioners as strategic communicators who actively build relationships,[23] rather than simple communication managers.

The 80-20 and 70-30 “Rules” of Content

Many organizations that experience success online follow two principles of content production: The 80-20 rule regarding focus, and the 70-30 rule regarding creation and curation.

The 80-20 rule, known as the Pareto Principle, contends that organizations should spend 80% of their time and content production on audience-relevant content, and just 20% of their time and production on content that’s specific to the company or their products and services.[24]

The 70-30 rule is based on the idea that organizations should create 70% of all online content and curate 30% of all online content. Created content should cater to a specific audience, and may include elements such as infographics and videos. The content that’s curated may be anything from articles and photos to videos and music created by others—but also has some kind of tweak from the organization, including the headline, a new image, or quotes pulled from the original that may “surprise, educate, and entertain” the audience.[25]

These two rules may not be etched in stone, but they are good general guidelines to consider when determining the appropriate content mix for an organization.

From an organizational perspective, relationship-building in online spaces is tough. There are three stages of interpersonal communication: An initial phase of interaction between strangers; a personal phase when individuals engage in an exchange of opinions, values and attitudes; and an exit phase where decisions are made regarding any potential future interactions.[26] The initial phase can be continuous for organizations, with a steady churn of new likes and follows. Moving beyond that initial phase can be difficult as long-time fans can become frustrated that their relationship with the organization doesn’t develop more fully.[27] Organizations might want to advance those relationships, but are typically reluctant to be vulnerable enough to do so, because they lack trust and confidence in the relationship.[28] The opportunity to engage means the organization will lose exclusive control of its messages as users react to and interact with those messages — and for many organizations, that’s too high a price to pay.[29]

For that reason, many organizations in recent years have outsourced the hard work of building relationships with influencers.

Influencers: Definitions & Types

First things first: Many professionals prefer “content creator” rather than “influencer,” because it recognizes the value and creativity of being an influencer.[30] Other than a preference in nomenclature, the terms refer to the same thing: A person who has clout with a particular audience.

As Jia Tolentino defined it, the status of being an influencer involves “the performance of an attractive life.”[31] Influencers tend to occupy the space between a friend and a celebrity[32]—with some overlap between those categories. From a Strategic Communication perspective, Influencers are “third-party actors that have established a significant number of relevant relationships with a specific…influence on organizational stakeholders through content production, content distribution, interaction, and personal appearance on the social web.”[33]

Just as there’s a lingering battle between the terms “content creator” and “influencer,” there are terms such as strategic influencer communication, influencer marketing, and influencer relations that—in practice—tend to have similar, overlapping meanings.[34] For our purposes here, we’ll go with a distinction between two terms: influencer marketing and influencer relationships. In some ways, it mirrors the distinction between PSI and PSR. Influencer Marketing characterizes a relationship with an influencer that’s undertaken for a specific campaign. Influencer Relationships describe long-term ongoing relationships with influencers that extend beyond a particular campaign.[35] This distinction matters.

There are four commonly used classifications for influencers that describe their reach: mega, macro, micro, and nano.[36] Mega-Influencers generally have at least 1 million followers on at least one social media platform. Macro-Influencers generally have 100,000-1 million followers; Micro-Influencers have several thousand—or tens of thousands—of followers, and Nano-Influencers have fewer than 5,000 followers.[37],[38],[39]

Bottle Rockets & Bonfires

Influencer marketing is transactional in nature, and influencer relationships have a more organic feel.

It can be tempting to court mega-influencers for a specific campaign, since that’s easy to sell to executives interested in reach and exposure. It’s been called a “hired-gun model” because you’re figuring out who could be paid to do something for the organization.

A practitioner referred to the transactional approach as “the bottle-rocket model” because:

“We light off all these different bottle rockets, and they’re cool for 5 seconds. And then they disappear, and then you’re like ‘We’re out of bottle rockets. Now what do we do?’

“For me, it’s about building a bonfire because a bonfire is like a beacon in the night that people come and gather around and share stories and it warms you. I always tell my team, ‘It’s great to have bottle rockets, but point them at the bonfire. Let’s keep stoking the fire.’”

The lesson: Don’t discount the value of micro- and nano-influencers who are perceived as credible and authentic by their loyal followers. Building those relationships over the long-term can yield dividends.

Working With Influencers

There are similarities and differences in working with influencers compared to other individuals and groups the organization does business with that are worth exploring. Some have argued that it requires new forms of relationship management, as influencers span the boundaries between creative agencies and advertising to journalists and opinion leaders. Therefore, influencers exist at the crossroads of marketing (traditionally selling products and creating brand awareness) and Public Relations (traditionally building relationships, reputation, and trust).[40] To be fair, those same observers have suggested that there is substantial overlap between working with influencers and traditional media relations, which manages an organization’s relationships with key media organizations and journalists that shape opinions.[41]

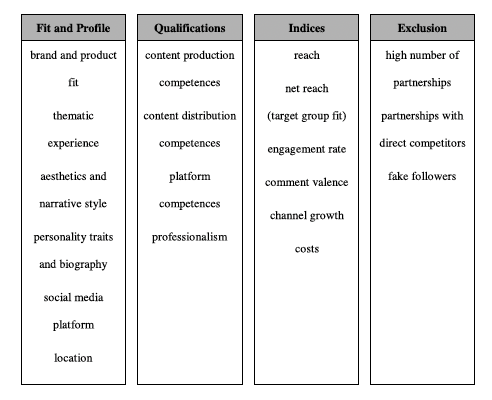

The first and most important step is to identify influencers that are a good fit for the organization. There are agencies that connect organizations and influencers, but it’s better to reach out directly because influencers value those direct relationships with the brand.[42]

The relationships between influencers and organizations are consistent with theories of relationship management generally: An open and honest dialogue is essential, as are feelings of control, mutuality, and listening.[43]

For larger organizations, the legal department will typically create the necessary paperwork that outlines the arrangement and is signed by both parties.[44] Beyond that step, it’s complicated.

One of the most common points of contention between organizations and influencers involves creative control.[45] Some organizations and marketers want to control the content as they would with traditional advertisements, and hand the influencer a script with strict guidelines and a set of expectations. The problem with that mindset is that the influencer can feel micromanaged, and believe that this purely transactional approach to the relationship will result in content that “feels” like an ad.[46]

It’s generally considered far more effective to choose influencers very carefully, set up a few guard rails, and let the influencer take it from there. That way, the influencer can create content that feels authentic to them and their audience, and lets them know they are a valued and trusted partner.[47]

Over time, and with an emphasis on relationships instead of one-time marketing, influencers tend to do things for the organization without the expectation of being paid every time. Another advantage of long-term relationships with influencers is that there becomes less of a need to find new influencers for each new campaign, and that can become a significant factor when time is of the essence.[48] These mutually beneficial relationships hedge against the risk of an influencer “going rogue” one day, while a more transactional relationship offers no such protection.[49] There’s some disagreement as to whether it’s appropriate for influencers to co-create campaigns with the organization, and such a decision becomes more reasonable if the influencer has a proven track record of successful campaigns.

The general tendency in these relationships is to start small at first, and then ramp up expectations when it goes well. Organizations and influencers that are a good fit typically have a mutual desire to deepen the relationship in a way that feels natural and authentic. That authenticity comes at a price, though: Sometimes difficult discussions need to happen when things aren’t going according to plan, and the relationship needs to be reassessed.

Finally, there are risks to relying upon influencers to communicate on behalf of an organization. From a practitioner perspective, adding influencers can become similar to instructions that are “just add water.” Almost anyone could do that, so why would a client pay an expert to tell them that? From an organizational perspective, outsourcing outreach to an influencer can prevent the organization from building those relationships on its own.[50] Furthermore, it’s not just content and relationship building that are being outsourced. The organization also becomes reliant on the influencer to share relevant dashboard analytics to determine the success of the initiative.

With respect to influencers and an overall strategy, it’s a “both/and” rather than an “either/or.” Influencers can be an effective part of a strategy, but they shouldn’t be the entire strategy.

Experts Talk Back:

Three Questions with Dana El-Shoubaki, Influencer Partnerships Manager.

Dana El-Shoubaki helps brands connect with content creators, and has worked primarily with companies selling beauty and fitness products.

Q: I’m curious as to how influencer collaborations might have changed during the last handful of years that you’ve been in that space?

I would say in the early influencer marketing days, influencers were just excited to be working with brands. It was more about free product and exposure, but now influencers are definitely demanding pay, which makes sense, because they can’t pay their rent with exposure or free product.

Brands are definitely pivoting to create a budget for that because they were definitely taking advantage of content creators back in the day. So content creators have found their voice, and now there are tools out there for content creators to figure out how much their rate should be: How much engagement do their posts get, how many followers, likes and saves?

There are analytics on the social media side, so being able to understand those analytics and how you can better pitch yourself as a content creator to those brands. Then they can see: “Oh, this person drives a lot of traffic to the website. People actually use this person’s promo code.” That gives the brand more of a reason to actually pay influencers rather than when they’re just like, “This is how many likes I get,” and they’re like, “But does it translate to sales?” In the beginning, they weren’t sure how to calculate that ROI, and now brands know how they want to calculate it rather than just “impressions.” Impressions aren’t enough now, and I was like “we need money!”

Q: In one of your responses, you mentioned working with micro-influencers. Have you found any sort of basic level of followers—whether it’s mega- or macro- or micro- or nano—is potentially more effective on the brand side of things than others? Or does that just depend upon the particular client and content creator?

I would say “yes” to the first part.

So when I was at Benefit [Cosmetics], I was really focused on building out and scaling their first micro-influencer program. And the reason for that is that consumers are more inclined to trust micro-influencers because they have a smaller following. They’re not getting as many brand partnerships. It’s more that they’re putting out the content because they like these products.

Consumers see them as more genuine than people who have hundreds of thousands of followers—or millions—because then they’re like, “Oh, this might just be an ad. This might just be for a paycheck.” And you’ll still see the comments where they’re still in support of that influencer, like “Yeah, get your coin!” or comments like that.

Consumers are smart. They know when they’re being marketed to. They view people with a smaller following as more trustworthy than users with a larger following. You do see that shift once you get to influencers who are in the millions range, because they built that million-follower range for a while. So people who follow them know if they’ve been using this product for a few years rather than just a month ago. They keep up with that influencer, and know what they’re about.

Q: What advice do you have for students who are graduating in the next few years in public relations and strategic communication in terms of skill sets, things that would be good to know, soft skills—that sort of thing—as they are about to enter the workforce?

Internships are definitely beneficial. Try to do them as soon as you can. Even if they’re not paid, if you’re in the space and can take an unpaid internship, do it. It just opens up your professional network. For me, I had different roles. So I was able to see, “Do I like this? No, I like this more.” You learn things from your internships.

Network with your peers. You never know who knows who.

Learning how to negotiate is also huge. It’s very critical. Not only negotiating for yourself, but if you get into a rule of influencer marketing, you’re often negotiating contracts with influencers for the brand.

So those would be my top three: Internships. Network. Negotiate.

Another thing I would say is that everyone’s on their own path. So, you might see a peer get an internship or a job right out of college, but that might not be your case. Everyone’s on a different path. It’ll come to you.

And it’s also okay if you don’t end up working in the field you graduated in.

Data Analytics: KPI’s & the Zero Point

Data Analytics refers to the science of analyzing “crude data to extract useful knowledge (patterns) from them.”[51] Social media dashboards are chock-full of metrics, and each platform is slightly different. There are analytics tools that are unique to, and have specific meanings for, each platform—like what counts as a “view,” for example. That’s why there are detailed guides on how to interpret analytics for X (formerly known as Twitter), Meta (Facebook and Instagram), TikTok, LinkedIn, and Pinterest.

There’s more data on those dashboards than is meaningful, and it’s up to the practitioner to first determine—based on the goals and objectives of the organization — which of those analytics matter, and why. A Key Performance Indicator, or KPI, is something that’s important enough to measure, and should be a metric that facilitates the decision-making process. It’s a widely used term in business, beyond the world of social media. A KPI stands in contrast to what are referred to as “vanity metrics,” which are data that may look impressive, but don’t yield any actionable information. KPIs clarify what needs to be done to improve outcomes; vanity metrics do not.

A good KPI is something that can be:

(1) actionable — based on the changes of value in the metric;

(2) understood by everyone — especially those who need to see it;

(3) from a credible source and easily accessed;

(4) easy to calculate — for the social team and other stakeholders.[52]

Matching Goals & Objectives with KPIs

Aligning Business Goals & KPIs (usually Intermediate Metrics, in the case of Social Media) for Business Success

| Business Goals | KPI 1 | KPI 2 | KPI 3 | KPI 4 | KPI 5 |

| Awareness | Share of voice | Social community growth | Reach, volume of conversions | Sentiment analysis (+/- neutral) | Unique commenters |

| Engagement | Interactions per follower | Daily active users | % of community interacting | Viral content spread | Hashtag/meme use |

| Lead Gen | Cost to acquire leads from social | Web referrals via social media | Qualified sales leads via social | Growth of reach in targeted audiences | Number of downloads of select content |

| Conversion | Downloads via tracked links | Revenue via tracked links | Cost per acquisition (CPA) | Increase % of social conversions | Revenue attribution via influencers |

| Customer Support | Cost savings | Decreased time of issue resolution | Sentiment change on support issues | Number of issues resolved | Resolution rate per issue/agent |

| Advocacy | Number of active advocates | Volume of advocate conversions | Volume of brand advocates conversions | Influence score and reach of advocates | Revenue attributed to advocates |

| Innovation | Number of ideas submitted related to products or services | Number of ideas that are developed into products or services | Number of bugs that are fixed in developed products or services | Community feedback from development of products or services | Engagement rate in product forums |

KPI’s are determined by the goals & objectives of the organization. Table from Sponder & Khan (2019).

Finally, we’ve all seen “before and after” photos, usually from a company trying to sell pills, creams, and lotions for things ranging from weight control to hair growth or skin care. But there’s also a “before and after” involved with social media analytics. Before any moves are made on behalf of an organization, it’s essential to document the Zero Point, which is the status of all social media accounts before implementing a new strategy for the organization. This includes not only which platforms the organization actively uses, but also its number of followers, engagement rate, and other metrics that are deemed relevant based on the organization’s goals and objectives. It’s impossible to demonstrate progress if the starting point is unclear, so bring receipts. Document the zero point with screen grabs so that the client—and prospective clients—can see the difference for themselves.

How to Track Social Media Performance

Understanding Analytics

Remember, data analytics isn’t just about staring at numbers on a dashboard. It’s about studying the relevant data points and looking for patterns that will determine the appropriate next steps.

One initial way to look at analytics is whether the data is descriptive, predictive, or prescriptive. Descriptive Analytics asks “What happened?” and offers insights into the past. Predictive Analytics asks “What could happen?” and offers insights into the future. Prescriptive Analytics asks “What should the company do?” and offers possible courses of action.[53] These distinctions are perhaps more interesting in theory than in practice, since descriptive analytics, such as likes, views and comments, accounts for the vast majority of analytics today.[54] The balance between descriptive, predictive, and prescriptive analytics may shift in the years ahead due to Artificial Intelligence, and it’s hoped that AI may streamline the process. In Summer 2023, Google Analytics 4 was rolled out, which tracks a customer’s interactions across websites and apps, uses AI to fill in gaps in data, and utilizes predictive metrics to anticipate future customer actions.[55]

Differences Between Social Monitoring & Social Listening

Both monitoring and listening are necessary parts of any social strategy. There is some disagreement as to what constitutes monitoring and listening, but we’ll use the following distinction.[56]

Social Monitoring involves answering questions, resolving issues and complaints, and thanking customers for positive feedback. It’s a public action that involves more individual observers than participants.

Social Listening tracks social mentions to determine which platforms are used most by the audience, how frequently the brand is mentioned relative to the competitors, and whether the industry itself is frequently discussed.[57]

| Social Monitoring | Social Listening |

| Current | Future |

| Customer Interaction | Data Analysis |

| Micro-level | Macro-level |

| Possible without tools | Requires tools |

Another practical way to approach analytics is to evaluate metrics by the type of data it yields. There are thousands of metrics, so being able to toss each one into a “bucket” based on its purpose can help determine relevant KPIs. Much of this chapter focuses on establishing and building relationships, and the social media experts at Buffer conjured up six categories of metrics: activity, reach, engagement, acquisition, conversion, and retention, and advocacy.[58]

Activity metrics refer to the output of the social media team—posts, scheduled content, problem-solving, and answering questions—and can be useful to show the organization what’s been done. That data can also be useful in determining if an increase in one area results in an increase in another area.

Reach metrics examine the organization’s audience and potential audience, and include everything from the number of followers to the growth rate of the audience, as well as sentiment and share of voice. Organic Reach refers to reach without the benefit of advertising or promoting the content in any way.

Engagement in the world of analytics refers to interactions and interest in the brand, as well as how people react to and share the organization’s content. One common metric is the engagement rate, or the number of reactions, comments, or shares content gets (generally as a percentage of the overall audience). If that percentage seems low, don’t worry: 1%-5% is common across most industries.[59] Here’s a quick guide to calculate those numbers.

Acquisition describes the next stage of the customer-organization relationship, as it focuses on customer’s experience on apps and websites. Common metrics include the number of subscribers and bounce rate—or the percentage of visitors who went to a single page and immediately exited. A basic premise is that people may start by casually chatting about the brand online, but then dig a little deeper on the website or app when the brand piques their curiosity.

Conversion may refer to any number of things, whether it’s a download, signup, subscription, or sale. The definition of conversion depends entirely on the goal. A common metric is the conversion rate, which is the percentage of users that take a desired action (dividing the number of conversions by total traffic).

Finally, Retention and Advocacy refers to the loyalty of customers as they become brand evangelists. Basic metrics include the customer retention rate (compared to those who have canceled), reviews and ratings, and overall customer satisfaction.

Again, focus first on the goal and objective, and look to relevant KPIs to assess and act upon. Depending on the needs of the organization, it may be prudent to focus more on reach and engagement—or perhaps how to nudge customers in the acquisition or conversion phases.

Summary: Putting It All Together

People form opinions of and build relationships with people and brands online, as parasocial interactions develop into parasocial relationships.

Many of those relationships follow a similar set of rules and expectations as we have in interpersonal relationships.

Influencers are called upon more frequently by brands as a shortcut of sorts, because they already have good relationships with target audiences. Those partnerships come with some risk, however, so great care must be taken in the selection process.

Data analytics are critical to understanding the problem, charting a path forward, and understanding what success looks like. Begin with a goal/objective, connect that to KPIs, and set up processes for monitoring and listening.

Above all else, remain flexible because “no two social strategies will look the same. Social strategies are unique to each company and each brand.”[60]

This chapter examined the rules of the road for social media, and how to conceptualize it from a Strategic Communication perspective. The following chapter builds on these themes and explores how to craft and implement effective social media strategies.

Media Attributions

- Sport fans © Omar Ramadan is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Influencers © George Milton is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- FIT graphic

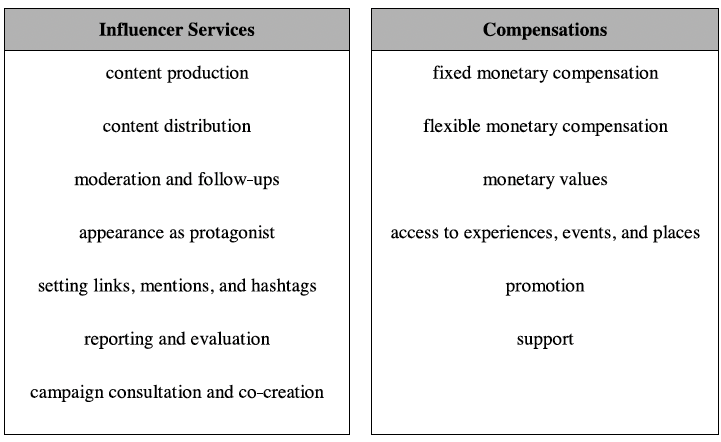

- Influencer services and compensation

- Ammerman, W. (2019). The Invisible Brand: Marketing in the Age of Automation, Big Data, and Machine Learning. McGraw Hill. Page 115. ↵

- Groening, M., Brooks, J.L., & S. Simon (Writers). (1999, May 16). Thirty minutes over Tokyo (Season 10, Episode 23). The Simpsons. Gracie Films: Twentieth Century Fox Film Productions. ↵

- Morales, C. (Oct. 7, 2020). “Millions of views later, Nathan Apodaca keeps the vibe going,” The New York Times. ↵

- Allyn, B. (Oct. 11, 2020). “TikTok sensation: Meet the Idaho potato worker who sent Fleetwood Mac sales soaring,” NPR. Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/2020/10/11/922554253/tiktok-sensation-meet-the-idaho-potato-worker-who-sent-fleetwood-mac-sales-soar ↵

- Gordon, E.A. (March 24, 2023). “The Cranberry juice-drinking, longboarding warehouse worker who made Stevie Nicks join TikTok,” Pop Dust. Retrieved from: https://www.popdust.com/nathan-apodaca-2648208897.html ↵

- Dunn, R. (Dec. 25, 2023). “How much did Idaho’s viral sensation Nathan Apodaca make in 2020?” Listen Boise. Retrieved from: https://www.listenboise.com/trending/how-much-did-nathan-apodaca-make ↵

- Sentence from manuscript draft of chapter, “The future of public relations, according to AI,” submitted to Public Relations in 2050, A. Laskin & K. Freberg, eds., Routledge. ↵

- Sponder, M. & Khan, G.F. (2018). Digital Analytics for Marketing. Routledge: New York. ↵

- Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2013). Spreadable media: Creating value and meaning in a networked culture. New York University Press. ↵

- “Text” is an all-encompassing term that may include published media ranging from books and songs to television shows and movies. ↵

- Gray J. (2003). New audiences, new textualities: Anti-fans and non-fans. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 6(1), 64–81. 10.1177/1367877903006001004 ↵

- Horton, D. & Wohl, R.R. (1956). Mass communication and parasocial interaction: Observations on intimacy at a distance, Psychiatry, 19: 215-229. Pages 215-216. ↵

- Hu M. (2015). The influence of a scandal on parasocial relationship, parasocial interaction, and parasocial breakup. Psychology of Popular Media Culture. doi:10.1037/ppm0000068 ↵

- In a 2019 meta-analysis of PSI and PSR related studies, it was determined over a 60-year period that two-thirds of all peer-reviewed work had been published in the last 10 years. See Liebers, N. & Schramm, H. (2019). Parasocial interactions and relationship with media characters—an inventory of 60 years of research, Communication Research Trends, 38(2): 4-31. ↵

- Rubin R. B. McHugh M. P. (1987). Development of parasocial interaction relationships. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 31(3), 279–292. 10.1080/08838158709386664 ↵

- Cohen J. (2004). Parasocial break-up from favorite television characters: The role of attachment styles and relationship intensity. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21(2), 187–202. 10.1177/0265407504041374 ↵

- Giles D. C. (2002). Parasocial interaction: A review of the literature and a model for future research. Media Psychology, 4(3), 279–305. 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0403_04 ↵

- Paquette, M., Sommerfeldt, E.J., & Kent, M.L. (2015). Do the ends justify the means? Dialogue, development communication, and deontological ethics. Public Relations Review, 41(1): 30-39. ↵

- Littlejohn, S.W. & Foss, K.A. (2008). Theories of human communication (Ninth ed.)., Belmont, CA: Wadsworth. Page 3. ↵

- Li, C. & Kent, M.L. (2021). Explorations on mediated communication and beyond: Toward a theory of social media, Public Relations Review, 47: 102112. ↵

- Kent, M.L. & Theunissen, P. (2016). Elegy for mediated dialogue: Shiva the Destroyer and reclaiming our first principles. International Journal of Communication, 10: 4040-4054. ↵

- Kent, M.L., Lane, A. (2021). Two-way communication, symmetry, negative spaces, and dialogue, Public Relations Review, 47: 102014. Page 1. ↵

- Li & Kent, Ibid. ↵

- Luttrell, R. (2019). Social Media: How to Engage, Share, and Connect, 3rd ed., Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD. Page 33. ↵

- Luttrell, Ibid., pp. 90-94. ↵

- Berger, C.R. & Calabrese, R.J. (1975). Some explorations in initial interaction and beyond: Toward a developmental theory of interpersonal communication. Human Communication Research, 1(2): 99-112. ↵

- Li & Kent, Ibid. ↵

- Lane, A.B. (2014). Pragmatic two-way communication: A practitioner perspective of dialogue to the practice of public relations. Unpublished PhD thesis. Brisbane, Queensland, Australia: Queensland University of Technology. Originally cited in Li & Kent, Ibid. ↵

- Truong, H-B., Jesudoss, S.P., Molesworth, M. (2022). Consumer mischief as playful resistance to marketing in Twitter hashtag hijacking, The Journal of Consumer Behavior, 21(4): 828-841. ↵

- Confirmed in interviews with Ian Anderson and Dana el-Shoubaki. ↵

- Gilbert, S. (2019, January 22). Millennial burnout is being televised, The Atlantic, Retrieved from https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/01/marie-kondo-fyre-fraud-and-tvs-millennial-burnout/580753/ ↵

- Blanche, D., Casalo, L.V., Flavian, M. & Ibanez-Sanchez, S. (2021). Understanding influencer marketing: The role of congruence between influencers, products and consumers. Journal of Business Research, 132: 186-195. ↵

- Enke, N. & Borchers, N.S. (2019). Social media influencers in strategic communication: A conceptual framework of strategic social media influencer communication. International Journal of Strategic Communication, 13: 261-277. Page 267. ↵

- Smith, B.G., Golan, G., & Freberg, K. (2023). Influencer relations: Establishing the concept and process for public relations, Public Relations Review, 49: 102305. ↵

- Borchers, N.S., & Enke, N. (2021). Managing strategic influencer communication: A systematic overview on emerging planning, organization, and controlling routines, Public Relations Review (47): 102041 ↵

- There are some additional variations of this, as observers and practitioners have been shown to refer to Mega Influencers as “Celebrity” Influencers, Macro Influencers as “Mid-Tier” Influencers, and some who eliminate “Nano” as a category, grouping that with other Micro Influencers. ↵

- Kahn, E. (2017, December 18). How to work with influencers in 2018. PR Week, Retrieved from https://www.prweek.com/article/1453015/work-influencers-2018 ↵

- Maheshwari, S. (2018, November 11). “Are you ready for the Nanoinfluencers?” The New York Times, Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2018/11/11/business/media/nanoinfluencers-instagram-influencers.html ↵

- Seavers, D. (2019, March 15). Report: Nano-influencers offer big upsides for marketers, PR Daily, Retrieved from https://www.prdaily.com/report-nano-influencers-offer-big-upsides-for-marketers/ ↵

- Borchers & Enke, Ibid. ↵

- Borchers & Enke conclude Influencer Relations and Media Relations are “distinct” from one another because of “different control mechanisms” including “contractual relationships, payment, and control and approval processes,” as well as the “resources that influencers commit to collaborations such as the relationships to their audiences, trust, and interactions go beyond media organizations capacities.” Page 11 ↵

- Smith, Golan & Freberg, Ibid. ↵

- Ledingham, J.A., & Bruning, S.D. (1998). Relationship management in public relations: Dimensions of an organization-public relationship. Public Relations Review, 24(1): 55-65. ↵

- Borchers & Enke, Ibid. ↵

- Smith, Golan & Freberg, Ibid. ↵

- Borchers & Enke, Ibid. See also Smith, Golan & Freberg, Ibid. ↵

- Borchers & Enke, Ibid. See also Smith, Golan & Freberg, Ibid. ↵

- Smith, Golan & Freberg, Ibid. ↵

- Smith, Golan & Freberg, Ibid. ↵

- Borchers & Enke, Ibid. ↵

- Moreira, J.M., de Carvalho, A.C.P.L.F., Horvath, T. (2018). A General Introduction to Data Analytics, United Kingdom: Wiley. Page 4. ↵

- Sponder & Khan, Ibid. ↵

- Khan, G.F. (2015). Seven Layers of Social Media Analytics: Mining business insights from social media. Leipzig: Verlag Nict Ermittelbar. Cited in Tufekci, Z. (2019) “Measuring social media’s impact and value,” pp. 158-169 in Social media: how to engage, share and connect, R. Luttrell ed., (3rd ed.) Rowman & Littlefield: New York. ↵

- Tufekci, Z. (2019) “Measuring social media’s impact and value,” pp. 158-169 in Social media: how to engage, share and connect, R. Luttrell ed., (3rd ed.) Rowman & Littlefield: New York. ↵

- Shafiq, V. (2022, March 29) “Why you should get on board with Google Analytics 4 today,” Location3.com. Retrieved from: https://location3.com/research/white-paper-getting-on-board-with-google-analytics-4/ ↵

- For example, Freberg (2019) contends that Monitoring refers to a systematic process of understanding and reporting insights, and can take place over months or years. Listening is typically more short-term and attempts to uncover trends. ↵

- Chen, L. (2022, October 5). Research in social media: Monitoring, listening, and analytics. Personal Collection of L. Chen, Weber State University, Ogden, UT. ↵

- Seiter, C. (2015, March 12). 61 key social media metrics, defined. Buffer. Retrieved from: https://buffer.com/resources/social-media-metrics/#Acquisition ↵

- Sehl, K. & Tien, S. (2023, Feb. 22). Engagement rate calculator + Guide for 2024, Hootsuite. Retrieved from: https://blog.hootsuite.com/calculate-engagement-rate/ ↵

- Luttrell, Ibid., p. 49. ↵