2 History: How We Got Here & Where Ideas Come From

Nathan J. Rodriguez, Ph.D.

“The past is never dead. It’s not even past.”

—William Faulkner, Requiem for a Nun

“We need, in every community, a group of angelic troublemakers.”

—Bayard Rustin

First, a Story…

The year is 1809.

Newspapers in New York are informed that famous Dutch historian Diedrich Knickerbocker has disappeared from the Columbia Hotel on Mulberry Street.

The notices to the newspapers characterize him as likely not in his right mind, and they say that newspapers would be “aiding the cause of humanity” by alerting the public.

Weeks passed, and Knickerbocker is still nowhere to be found. Some New York officials are concerned enough to offer a reward for his safe return.

Seth Handaside, the hotel’s landlord, informs the same papers that a “very curious” book was found in Knickerbocker’s room, “in his own handwriting,” and that if Knickerbocker does not return to satisfy his debts, the manuscript will be published to recoup expenses.

The book, “A history of New-York from the beginning of the world to the end of the Dutch Dynasty,” is then published amid much fanfare.

As it turned out, the famous Dutch historian named Knickerbocker did not exist, nor did the landlord named Handaside. Even the hotel and street name were fictional. The characters and manuscript were figments of 26-year-old Washington Irving’s imagination.

a fictitious character. Image available in public domain, courtesy of Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

Enough people at the time believed the story. And the attention from the fake news meant that Irving was able to launch his literary career. He would become the first American to write as a primary means of income, rather than a side gig — and it all began with what would charitably be described as a pseudo-event or publicity stunt.[1]

The Takeaway

Washington Irving wouldn’t have thought of himself as a public relations practitioner, but through his actions, he would certainly be thought of as practicing public relations, or PR.

So, is Public Relations and Strategic Communication a profession or a set of actions?

We’ll cover that and more over the next few pages.

For now, it’s safe to say the history of PR extends further into the past than might be expected, filled with literal (and figurative) saints, revolutionaries and reformers, shameless self-promoters, and outright con artists.

We will learn about it and learn from it.

Introduction to the History of PR & Strategic Communication

Let’s say you’re out riding a bike one day.

Someone may say, “Oh, I didn’t know you’re a cyclist.” and you might reply, “I’m just out riding my bike, but I wouldn’t consider myself a cyclist.”

There’s a distinction between the act of riding a bike and being considered a cyclist.

Similarly, you can look through history and see examples of individuals who use public relations strategies and tactics, but who wouldn’t consider themselves PR professionals. We can still learn from them.

To push the bicycle metaphor a little bit further, focusing only on official PR practitioners is akin to focusing only on participants in the Tour de France. It ignores the lessons we could learn from riders who commute through congested city streets and even some tricks from wildly inventive BMX riders who might inspire us.

This is a roundabout way of saying that we’re not just going to examine PR professionals who chose to work for giant corporations and call that “PR history.” There’s a rich legacy of activists and social movements who worked from the same toolbox as PR practitioners, and they changed the course of history. Simply put, PR is both a profession and a practice that a whole range of people use.

Pre-modern PR: “A rose by any other name…”

As mentioned in Chapter One, PR is “notoriously difficult to define, which makes it hard to pinpoint its origins.”[2] The truth is, we know very little about the history of Public Relations practices prior to the 20th century.

An exhaustive 83-page study of PR history before 1900 concluded that “the birth of Public Relations was not identified; there was no discernible starting point, founding date, or incubation period,” and also that “no area of Public Relations history has been adequately researched.”[3]

The basic function and purpose of Public Relations have remained the same throughout history — only the technological tools have changed. A view of the history of PR is only limited by someone’s interpretation of historical events.

It could certainly be argued that ancient monuments built several thousand years ago were attempts at strategic communication, providing a message to outsiders and attempting to unify the local population.

In that 83-page study, the authors, Lamme & Russell, contend that “the intentional practice of Public Relations is at least 2,000 years old.”[4] In a way, Public Relations has always been around, and it’s been called different names over time. The term Public Relations was being used by the press in the 1700s, and by the 1830s, the term was generally being used in the same context as it is today.[5]

There are five basic motivations for PR that surface across different times and industries: “Profit, including sales and fundraising; Recruitment, including customers, volunteers, converts and employees; Legitimacy, including individual and organizational; Agitation, meaning efforts designed to work against something or someone; and Advocacy, meaning efforts designed to work for something or someone.”[6]

If we use a relatively broad definition of Public Relations, we begin to see it throughout history — when Sparta emphasized its victories and downplayed its defeats during the Persian War in Ancient Greece, when Genghis Khan sent forth an advance team that “grossly exaggerated the size and cruelty of his armies,” or when Louis XIV unabashedly promoted and defended France.[7] The list of historical examples is limited only by the interpretation of events. For that reason, we’ll limit our overview to the U.S., and focus primarily on the past 100 years.

PR in the United States: The Early Years

Figures and foundational documents from the American Revolution are examples of Public Relations in action, as several strategies and tactics were developed with the goal of declaring independence and forming a new nation.

A wide range of documents from the founding of the U.S. may be considered “examples of the power of Public Relations.”[8] Prior to the American Revolution, Thomas Paine outlined the unfair treatment of colonists by Great Britain by sending “The Crisis Papers” to colonial newspapers—often characterized as “a series of press releases.”[9] Similarly, to help promote the value of the new American government, Alexander Hamilton, James Madison and John Jay wrote the Federalist Papers to support the Constitution. Some have even called this act “the greatest work ever done in America in the field of Public Relations.”[10]

But perhaps the best example was Samuel Adams, who used more than 24 pseudonyms and wrote hundreds of essays attacking England, all intended to provoke crises to lead the colonies to break away from Britain. Adams used newspapers and pamphlets to encourage colonial Americans to engage in an insurrection. Through that work, historians would later consider him to be “the father of press agentry” and someone who was the “progenitor” of “today’s public relations specialists.”[11] It’s been said that had Adams and others not relied on the “press, posters, speeches” and “symbolic gestures with the sustained saturation” that they did, the American Revolution might have never happened.[12]

Legends of the Old West

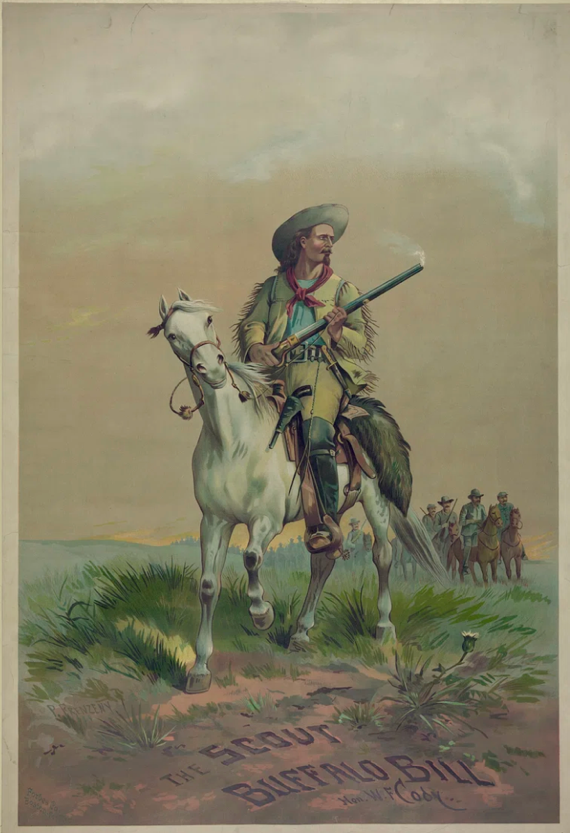

Some of the most well-known names related to westward expansion in the 18th and 19th centuries, including Daniel Boone and Buffalo Bill Cody, are famous for successful Public Relations efforts.

Daniel Boone was an actual person, but his myth was created in the 1780s. Boone and his business partners were land speculators, buying and selling tens of thousands of acres, and they wanted to sell land in Kentucky.[13] They wrote a guidebook for the state of Kentucky, which included a chapter on “The Adventures of Colonel Daniel Boone[e].”[14] The guidebook was a hit, and catapulted Boone into the status of one of the earliest folk heroes in the emerging United States of America. Within a year, copies of the text circulated throughout Europe, and Boone was celebrated as a symbol of the American spirit.[15]

In an unfortunate twist of fate following Boone’s death, a range of individuals and organizations attempted to hijack his image to achieve their own ends, including groups who were antagonistic toward Native Americans. They attempted to redeploy Boone as someone who hated Native Americans, although he had developed enduring friendships with a number of Native Americans during his lifetime.[16]

William Frederick Cody would be better remembered as “Buffalo Bill.” He was also an actual person whose image was crafted in part by his own actions and in part by the actions of his press agent and another writer who loved a good story.

Ned Buntline was that writer. He originally wanted to write a novel about Wild Bill Hickock and tried to pitch Hickock on the idea. That didn’t go well. As legend has it, Wild Bill pulled out a gun and told Buntline to leave town.[17] It’s believed that Buntline continued to interview Hickock’s friends and, after meeting William Cody, decided that Cody might make for an even better story. Buntline claimed credit for the “Buffalo Bill” nickname, saying he created it for the series he was writing for New York Weekly entitled “Buffalo Bill, the King of the Border Men.”[18]

Cody’s press agent, John Burke, also helped to “spread Cody’s fame by turning out stories, providing interviews, and inventing new myths.”[19] Burke also published a massive 750+ page book that linked the near-mythical figures of Daniel Boone, Davy Crockett, and Kit Carson with Buffalo Bill Cody.[20]

Advocacy & Social Movements

At this point, we’ve covered the spectrum of motivations — profit, recruitment, legitimacy, agitation and advocacy — and it should be clear that these motivations can and do overlap.

Scholars have identified the 1840s as a period when activists began to strategically use emotional appeals to persuade audiences.[21] The first women’s rights convention, held at Seneca Falls in 1848, was organized by women who each had experience in the abolition movement and “expertise in the strategies and tactics of public opinion campaigns.”[22]

A few decades later, Clara Barton, first known as “The Angel of the Battlefield” during the Civil War, established the American National Red Cross. She employed an array of tactics: “letters, speeches, items for the press, handbills, congressional visits, and an eight-page pamphlet.”[23] Her efforts were further amplified by four journalists who were charter members of the organization, three of whom wrote for the Associated Press.[24]

Our final example of Public Relations advocacy is conservationist John Muir. He lived in Yosemite from 1868-1874, fell in love with the beauty of the area, and originally wanted to protect it from being damaged by livestock.[25] He teamed up with editor Robert Underwood Johnson, and they successfully lobbied Congress to create Yosemite National Park in 1890.[26] Two years later, he co-founded the Sierra Club, and his efforts in writing scientific articles for magazines, penning hundreds of letters, and lecturing across the nation led to the creation of Sequoia National Park and the Grand Canyon.[27]

PT Barnum & Press Agentry

In those same decades — the 1840s through the 1880s — emerged one of the first business persons in the U.S. to use PR tactics to generate profit: Phineas Taylor Barnum, better known as PT Barnum.[28]

He’s widely quoted as saying, “There’s a sucker born every minute,” but that phrase was actually something said about Barnum, not by him.[29] Barnum owned a museum in New York City filled with “human curiosities” and took the show on the road, calling it “PT Barnum’s Grand Traveling American Museum,” about 20 years prior to Barnum & Bailey’s Circus.[30]

In his early days, Barnum sometimes bribed editors for newspaper coverage[31] — usually around $20-$40, equal to about $1,000 in 2024 currency. He eventually became a source of fascination on his own accord. His name was synonymous with “showmanship.” More than 82 million people visited his New York museum, and throughout his lifetime he entertained a range of celebrities and politicians, including Mark Twain, Abraham Lincoln and Queen Victoria.[32]

Barnum later became involved in politics and agitated against racial discrimination and prostitution,[33] while also advocating for recognizing Black men and women as citizens in the U.S.[34] At the same time, he admitted having owned and even whipped enslaved people when he lived in the south. He lamented, “I ought to have been whipped a thousand times for this myself.[35] It may be argued that Barnum deserves credit for both philanthropic work and political advocacy late in life,[36] but his legacy is complicated at best. At the very least, he was a product of his time and place and among the first — but far from the last — to generate publicity by any means necessary.

Railroads & the Professionalization of PR

Public Relations and Strategic Communication may be viewed as a set of actions or a distinct profession.

Thus far, we’ve looked at historical precursors — actions — that have used PR strategies and tactics. In the mid- to late-1800s, there finally emerged a professional industry around the idea of Public Relations. If we adopt a strict view of PR as a professional occupation, then the railroad industry was perhaps the first to have PR practitioners on its payroll.

In the 1850s, railroad companies “led the way with paid agents” to steer public opinion in their favor.[37] They connected with journalists and politicians from local communities, provided free tickets to opinion leaders, and organized field trips for clergy and teachers.[38] Some wealthy patrons were even taken on a buffalo hunt with Buffalo Bill.[39] By the 1880s, amid westward expansion, the railroad companies employed around 30 to 40 in-house PR experts and were thus at the forefront of Public Relations professionals serving business interests.[40]

By the 1890s, some journalists had changed professions and went into Public Relations, marking the beginning of a tenuous relationship between journalists and PR practitioners.[41] One of the central figures in the early days of PR had connections to both the railroad industry and journalism: Ivy Lee.

Muckraking

Journalism and Public Relations are two sides of the same coin. The Muckraking era of journalism, from the 1890s-1920s, was a high point for investigative writing designed to change society. Though “muckraking” was intended to be a derogatory term for reporters who exposed corruption in big business, those reporters embraced the term as a badge of honor.[42]

People like Ida Tarbell took on Standard Oil, while Upton Sinclair’s “The Jungle” exposed conditions in the meatpacking industry, and Nellie Bly went undercover to report about patient abuse in mental hospitals. At the time, such stories were viewed as “publicity” regarding those entities. Businesses thus began to view their own efforts at publicity and Public Relations as something more than just promotion: They could use PR to defend themselves.

As historians put it, “…what really prompted the birth of contemporary public relations…was the reaction against the muckrakers with their new power to communicate with the masses…If publicity was being used to effectively attack business, why could it not be used equally well to explain and defend business?”[43]

Ivy Lee

A central figure in the birth of “modern PR” is “Poison” Ivy Lee[44], a former journalist for The New York Times, whose first client as a PR practitioner was the Pennsylvania Railroad. His predisposition toward transparency is reflected in his advice to “tell the truth because sooner or later the public will find out anyway.”

Lee is credited with writing the first corporate news release in 1906, which didn’t promote a business but detailed a train wreck in Atlantic City, New Jersey that killed more than 50 people. As PR counsel, Lee advised the railroad to provide reporters with rides to the scene of the accident.

Lee’s advice was in stark contrast to the prevailing practice at the time, which would have been to conceal some of the most tragic facts of the accident. The New York Times, and other outlets ran his news release verbatim, while also praising the railroad for its transparency.[45]

For all his contributions, however, Lee is not without fault. He represented the Rockefellers, a prominent oil tycoon family. He also defended mining companies by deploying factually inaccurate information during the 1913-1914 Colorado Coal Strike, which included the Ludlow Massacre. During this massacre, an anti-strike militia killed more than 20 people.[46] Lee would later go on to meet with Mussolini and Hitler several years before the start of World War II, and he would be interrogated by the House Un-American Activities Committee in May 1934 about his connections to Nazi Germany and anti-American propaganda.[47] He died later that year.

Lee preferred to call himself a “publicist” rather than a press agent. He felt that press agents (like P.T. Barnum, for example) had a negative reputation, and that a publicist was simply someone acting transparently on behalf of an organization. Historians at the time referred to him as “the first great figure” in the field and the “prototype of subsequent Public Relations counsels.”[48]

Fleischman & Bernays

Ivy Lee once told Edward Bernays that what Lee did was “art” and that it would die with him.[49] Public Relations and Strategic Communication is part art and part science. Bernays would bring the science to the field.

Doris Fleischman and Bernays were childhood friends who went on to marry, and are often credited with “founding” what’s referred to as “modern PR.” More accurately, Bernays typically receives a disproportionate amount of credit, while Fleischman’s contributions are barely mentioned.[50] Together, they were a formidable duo in the development of modern PR.

Bernays was a nephew of Sigmund Freud and incorporated a social science approach to the practice of Public Relations. He began as a music promoter and joined the United States Committee on Public Information during World War I, where he attempted to rally support for the Allied war effort. Bernays referred to his wartime work as “psychological warfare,” and he developed a new appreciation for the power of persuasion.[51] Following the war, he set out to apply what he learned within the world of business because, in his own words, “what could be done for a nation at war could be done for organizations and people in a nation at peace.”[52]

When Bernays opened his own PR firm in 1919, his first hire was Fleischman. Fleischman was a talented writer and editor. She wrote most of the news releases, articles, letters, and speeches sent out by Bernays and the firm.[53] Bernays and Fleishman marred three years later. He credited Fleischman with coining the term “Public Relations,” though scholars pushed back on that assertion, pointing out its usage by the railroad industry as early as 1897.[54]

Bernays is credited with writing what is widely considered to be the seminal text in Public Relations, Crystallizing Public Opinion, in 1923. The book is largely a collection of stories of the work Bernays did for his clients. The book was also an exercise in PR for the industry of PR: He wanted to move the entire field from the popular conception that PR was just for “circus promoters and publicity agents.”[55]

Torches of Freedom

In the late 1920s, women accounted for just one in eight cigarette purchases. The American Tobacco Company paid Bernays $25,000 — nearly half a million dollars today — to help convince more women to smoke.

Bernays rolled out a few ideas, first hiring an influencer — a well-known ballroom dancer, Arthur Murray, who encouraged people to reach for a cigarette when they felt “tempted to overindulge at the punch bowl or the buffet.”[56] The campaign worked, but women primarily smoked in private spaces, with the stereotype (reinforced in movies) that only devious women without morals would smoke in public. Bernays sought to recast cigarettes as a form of women’s liberation — as “Torches of Freedom.”

During the Easter Day Parade in 1929, a young woman named Bertha Hunt (Bernays’ secretary) stepped onto 5th Avenue in New York and created a scene by lighting a Lucky Strike cigarette. The press had been alerted to this defiant act in advance and were there to cover it as Hunt walked down the street with 10 of her friends. The New York Times ran a story the following day: “Group of Girls Puff at Cigarettes as a Gesture of ‘Freedom,’” and dozens of other newspaper outlets picked up the story. Some refer to Torches of Freedom as the “first” PR Campaign.

P.S.: Bernays loved the lore around Torches of Freedom and was never one to shy away from burnishing his legacy. It’s been said, -“The legend of that Easter Day parade grew each time Bernays told the story, and even though cigarette sales increased and Bernays maintained a relationship with the client for several years … the actual coverage was a bit more muted, dispersed and nuanced.”[57] And for the record, Bernays was said to personally oppose smoking, and tried to get Fleishman to quit. Their daughter claimed he would “snap them in half and throw them in the toilet.”[58]

It’s difficult, and perhaps unnecessary, to disentangle the work of Bernays and Fleischman. The key is that when the accomplishments of Bernays are discussed, remember Fleischman was likely the person doing much of the heavy lifting behind the scenes.

To help promote PR as a positive, Bernays often tried to contrast it from propaganda. He claimed the difference between propaganda and education was in perspective. “The advocacy of what we believe in is education,” he said. “The advocacy of what we don’t believe is propaganda.”[59] That comment provided a bit of an intellectual smokescreen for ideas and campaigns that would broadly be considered objectionable practices today.

In recent years, it’s been observed that he “repeatedly demonstrated that he regarded truth as liquid,”[60] and that there is a “contradiction between what Bernays said concerning the ethical behavior of a public relations counsel and what he did himself.”[61] In other words, while Bernays sought to create an aura of respectability for the profession, he didn’t behave as though those rules applied to his own work. It was a case of “do as I say, not as I do.”

The next chapter features a more detailed discussion of ethics, so in the meantime, a brief look at some darker moments in PR history will serve as cautionary tales.

Post-World War II: PR goes Bananas

But wait—there’s more bad stuff we need to discuss!

Public Relations practitioners have been involved in some shady dealings through the years. A timeline of “terrible moments in human history” from the last half of the 20th century isn’t fruitful because — whether through their own actions or those of professional practitioners — bad actors have relied on PR in their moment of crisis or anticipation of that moment.

Another Bernays-involved event concerns Chiquita bananas, known as United Fruit Company in the 1950s. Guatemala, Costa Rica, and other countries in the region were sometimes referred to as “banana republics” due to how much control the fruit companies exerted over the government and local population. In essence, United Fruit bribed Guatemalan government officials in the early 1900s, to lock in a deal that meant the fruit companies paid virtually no taxes and provided pennies a day to local laborers.[62] Colonel Jacobo Arbenz was democratically elected in 1951 by a 2-1 margin and began returning undeveloped land to farmers. At the time he was elected, just 2% of the population owned 70% of the land, and 90% of Guatemalan citizens were landless farmers.[63] Arbenz paid United Fruit what the company claimed the land was worth on their taxes (which the company had grossly undervalued), and a year later Arbenz transferred more than 200,000 acres to local workers and farmers.[64]

United Fruit hired Edward Bernays to help fix its Guatemala problem. This was the height of the “Red Scare” in the U.S., a time when Joseph McCarthy alleged the U.S. was being subverted from within by communist spies. Bernays used the U.S. media to spread stories that Arbenz was a communist and was taking orders from the Soviet Union.[65] It created a political frenzy. President Dwight D. Eisenhower didn’t want to take direct action, so he ordered the CIA (established just a half dozen years earlier) to recruit an opposition force to overthrow Arbenz. In June 1954, the CIA participated in and led the military coup. Arbenz fled the country and resigned from office ten days later. The new military dictatorship led to a civil war in Guatemala from 1960-1996 and an estimated 200,000 deaths.[66]

It’s too reductive to blame Bernays. United Fruit had a number of ties to influential figures in the U.S. government, but there’s no doubt he played a significant role in changing public perception. “… Most analysts agree that United Fruit was the most important force in toppling Arbenz, and Bernays was the company’s most effective propagandist.”[67]

Any chapter about history is a battle between depth and breadth.

Entire books have been devoted to the documented role of Public Relations in promoting the sugar industry.[68] In the mid-1970s, the PRSA awarded the U.S. Sugar Association with the prestigious Silver Anvil Award for its crisis communication campaign to limit FDA regulation of sugar.[69]

Then there’s the issue of Big Tobacco marketing to children and lying about the nicotine addiction in cigarettes, for which PR firms “helped to obfuscate or deflect the health question.”[70] And there’s also the fossil fuel industry funding campaigns to undermine science regarding climate change.[71] The list, unfortunately, goes on and on. The old adage that “history is just one damn thing after another” holds true.[72]

If you’re considering PR and Strategic Communication as a career, this hasn’t been the world’s best pep talk. But it’s important to understand that PR’s negative reputation is rooted in some questionable campaigns and practices. There’s no shortage of humans who will engage in dishonest acts for a few more dollars. And that’s why we need to take the concept of ethical behavior seriously. Our choices have implications for local communities across the globe.

PR & The Civil Rights Movement

Effective PR is essential to the success of any social movement.[73], [74]

Martin Luther King, Jr. was keenly aware of the importance of Public Relations and Strategic Communication.

As he put it, “Public relations is a very necessary part of any protest of civil disobedience…The public at large must be aware of the inequities involved in such a system [of segregation]. In effect, in the absence of justice in the…courts…nonviolent protesters are asking for a hearing in the court of world opinion.”[75]

Working with King was a lesser-known figure, who helped form strategic alliances, build relationships with key stakeholders, and coordinate events like the March on Washington from behind the scenes: Bayard Rustin. In 2023, Netflix released a documentary, Rustin, which presents a fuller picture of his life, but click below for a brief overview of his contributions to the movement:

TED-Ed: An unsung hero of the civil rights movement – Christina Greer

What were examples of PR strategies and tactics employed by Rustin?

Experts Talk Back:

Three questions with Dr. Karen Miller Russell, Jim Kennedy Professor of New Media at the University of Georgia. Dr. Russell is a prolific scholar whose work focuses primarily on the history of Public Relations.

Q: You’ve written obviously a lot about PR history and contributed quite a bit to that body of literature. I’ve seen a distinction of PR as a set of actions versus PR as a profession. I’m curious if you think that’s a fair distinction?

I think there is a distinction because I think there’s PR as an industry that has corporations and trade associations and trade press. And then there’s people just doing the activities that are all under the PR umbrella, but they’re not part of an industry.

They’re just probably working for a social movement or something that does not have that formal structure, but they’re still doing strategic things to communicate and achieve goals and all those kinds of things.

I think they both belong. I think they should both be included, but I do think there’s a difference.

Q: Just glancing through some PR history chapters in a lot of textbooks, students can be forgiven for believing Edward Bernays just fell from the sky one day and PR was born. I can’t stomach the idea that Bernays is the person who started all this because then you point to Doris Fleischman and Ivy Lee, and that’s just on the corporate side of things as well.

So, I do have some questions about Doris Fleischman and am curious to get your take on her contributions because I found it difficult to disentangle her work with Edward Bernays … She clearly deserves more credit than she’s been given in a lot of instances, but does she also deserve a little bit of blame for some of those more negative things Bernays did? How do you consider her contributions and overall legacy to the field?

That is so hard, because we don’t actually know what happened behind closed doors. We don’t know what she said or didn’t say, so what I’ve tried to do is say things like “The Bernays Agency” or “Bernays and Fleischman,” because you obviously can’t say “Oh, she did all the good parts behind the scenes, and he was the horrible one.” That’s not fair to either one of them…

I don’t like Bernays, so I’m not an expert in Bernays at all. And so I’ve tried to include what you have to, and — whatever. His daughter — that’s a complicated thing — I was on a panel with her one time and she really doesn’t like Bernays — her dad — at all. And I think that colors what she says about her mom, too. Take all of that with a grain of salt.

So I’ve just always tried to minimize them, and maybe I’m going too far the other way. But he’s been given so much credit! So in my AT&T book, I go back and their first publicity guy was in 1886 — so you cannot say that Bernays is the father of public relations. You can’t even say Ivy Lee is the father of public relations. So I always say PR has many parents. And that kind of points out how stupid it is to call it a father or a parent to begin with. No other professions have parents.

My take on early PR is that there were a lot of people experimenting and trying things from the 1880s to the 1900s. And then Ivy Lee formalized the agency structure, but there was also a lot of formalizing going on on the corporate side. So AT&T’s first information department was in 1905, which is the same time as Ivy Lee, so he’s clearly not the father either.

In the 19th century, people were not trying to create a profession, they were trying to solve a problem. And the problems were different depending on if you were an agency or a corporation or nonprofit or what have you. But they developed a lot of tactics and strategies, and then people come along and go, “Oh we can apply this.”

So by the time Bernays and Fleischman come along — it’s not new; sorry.

In fact, this week, I worked with Shelley Spector at the PR museum, and we’ve come up with several other people who were ahead of Bernays and Fleischman, including a husband and wife team: Zelda and Louis Popkin. He went by “Pop,” so “Pop Popkins.” So the husband and wife thing wasn’t new. And clearly what they did was just more publicity oriented, and what Bernays did was not — it was more strategic. But so was Ivy Lee, and so was my guy at AT&T — so I guess that’s why I minimize Bernays. I think he just took what everybody was doing and made a big splash about it and got all the attention.

Q: Lastly, what do you think PR students could learn from studying these case studies and history, and what advice would you have for students who are graduating in the next few years as they enter the PR and Strategic Communication field overall?

One thing you can learn from PR history is that it doesn’t stay the same. It’s constantly changing. And the people who don’t keep up, don’t keep up.

So it’s lifelong learning. It’s not like you finished school and now you’re done and you can do your PR career for the next 30 years based on what you know — that’s not it. There’s constant change and constant learning and paying attention to what other people are doing.

Just like the cases from history. What can I learn that’s good and bad from this, and recognizing that there’s both good and bad. There’s effective, and then there’s ethical — and those aren’t always the same. So applying a lot of the lessons from history can teach you what to do going forward.

The Study of Public Relations

The first class in PR was offered by Bernays at New York University in 1923, Following suit, other universities first began to offer courses in PR during the 1940s, which became more widespread over the next few decades.[76] PR as an official peer-reviewed academic discipline began in 1975 when the first academic journal for the study of PR, Public Relations Review, was founded.

Despite efforts to turn the practice of PR into a profession, as late as 1980, very few practitioners relied on PR theories or research in their work.[77] To be fair, they didn’t have much in terms of theories or research until the 1980s when academic journals “came alive,”[78] but even then, relevant theories were generally scattered across different areas of study, ranging from rhetoric, opinion formation, and mass communication to social psychology.[79]

In the late 20th century, there were functional differences between Public Relations, Advertising, and Marketing. Beginning in the 1990s, the internet and social media blurred those boundaries. We can make academic distinctions, but there is less of a functional difference in the fields. As one researcher put it, “PR 1.0” was more “top-down” in nature, focusing on news releases, managing accounts, and standard pitching, while “PR 2.0” is more “bottom-up,” with experts listening to consumers, creating content and stories, engaging with the community, and working with influencers and content creators.[80]

Strategic Communication is a more recent umbrella term that includes PR and is “transboundary,” broadly directed at using communication toward a specific end.[81] In a way, Strategic Communication is a return to the roots of PR and what Bernays envisioned Public Relations to be: an endeavor to interpret publics for a client and interpret the client for publics. It draws upon a wide range of ideas and tactics to do so.[82]

Summary: Putting it All Together

Public Relations may be viewed as a set of actions and a profession. Throughout history, Public Relations strategies and tactics have been used for the purposes of Profit, Recruitment, Legitimacy, Agitation and Advocacy.

There isn’t a precise starting point for the professionalization of Public Relations, still Lee and Bernays are often cited as the two key figures to mark the beginning of “modern” PR. Lee was more well-known in his day.[83] He introduced the idea of transparency with information and prioritized relationships with publics, from trading partners, employees, industry, the government, and local and global communities. He believed in using every means necessary — ranging from newspapers to “the radio, the moving picture, magazine articles, speeches, books, mass meetings, brass bands.”[84]

Lee was about 15 years older than Bernays and died in the 1930s, while Bernays lived to the age of 103 and passed away in 1995. Consequently, Bernays cemented his legacy as an industry leader, and he and Fleishman were able to refine their theory and practice of Public Relations of several decades and the height of mass communication.

Public Relations has a complicated history, and there have been attempts to distance present practice from the days of circus promotions, hoaxes, and propaganda. To be sure, the practice of PR has become “generally more sophisticated and ethical as time goes on.”[85] But it’s also critical to note that public relations strategies and tactics can mobilize communities and improve people’s lives, as we saw in examples ranging from organizing for women’s rights to forming the Red Cross and developing national parks.

In the 20th century, so-called “modern PR” was only referred to as “modern” because it “grew in concert with technological advances…and emerged from that landscape.”[86] The goals and objectives of Profit, Recruitment, Legitimacy, Agitation and Advocacy have remained the same for hundreds of years. Only the technological tools in our toolbox have changed.

Public Relations tactics and tools can create memorable, meaningful experiences and lasting change, but in the wrong hands, they can cause anything from temporary distress to destruction and death. This chapter reviewed some dark moments in history and provided examples of what not to do. The next chapter offers a guide to the ethical practice of public relations and strategic communication.

Media Attributions

- Washington Irving © Leprix, Paul, artist; National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- “Daniel Boone’s Arrival in Kentucky” © Highsmith, Carol M., artist is licensed under a Public Domain license

- William Cody Portrait © Frenzeny, Paul, artist is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Hiebert, R. E. (1966). Courtier to the crowd: The story of Ivy Lee and the development of public relations. Ames, Iowa: Iowa State University Press, p. 8. See also Jones, 2008, pp. 118-127 ↵

- Lamme, M. O., & Russell, K. M. (2010). Removing the spin: Toward a new theory of public relations history. Association for Education in Journalism and Mass Communication, p. 284. ↵

- Ibid., pp. 355-356. ↵

- Ibid., p. 354 ↵

- Myers, M. C. (2014). Revising the narrative of early US public relations history: an analysis of the depictions of PR practice and professionals in the popular press 1770-1918 (Doctoral dissertation, University of Georgia). Cited in Russell & Lamme, 2016. ↵

- Lamme & Russell, 2010, p. 335-336. ↵

- Kunczik, M. (1997). Images of nations and international public relations. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. pp. 153-160. ↵

- McKinnon, L.M., Tedesco, J.C., & Lauder, T. (2001). Political power through public relations. In R.L. Heath & G.M. Vasquez (Eds.) Handbook of Public Relations (pp. 557-563). Boston: Sage. ↵

- Hiebert, Ibid., p. 8. ↵

- Nevins, A. (1963). The Constitution makers and the public: 1785-2790. Address to the Conference of the Public Relations Society of America. Boston, MA: Foundation for Public Relations Research and Education. Cited in Lamme & Russell, 2010. ↵

- Lamme & Russell, 2010, p. 311, citing Lee, A. M. (1937). The daily newspaper in America: The evolution of a social instrument. New York: Macmillan. Also, Cutlip, S.M. (1976). Public relations and the American Revolution. Public Relations Review, 2, 11-24. ↵

- Cutlip, 1976, Ibid. ↵

- Cutlip, S. M. (1995). Public relations history: From the 17th to the 20th Century. The antecedents. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid., pp. 14-15. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Gidmark, Jill B. (2001). Encyclopedia of American Literature of the Sea and Great Lakes. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 222–23. ↵

- Streeby, Shelley (2002). American Sensations: Class, Empire, and the Production of Popular Culture (2 ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 3 ↵

- Cutlip, 1995, p. 176. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- McBride, G. G. (1993). On Wisconsin women. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press. ↵

- Ibid., p. 5 ↵

- Lamme & Russell, 2010, Ibid., p. 305. ↵

- Cutlip, 1995. ↵

- Yosemite, n.d. National Park Service. Retrieved from https://home.nps.gov/yose/learn/historyculture/muir.htm ↵

- Schaffer, Jeffrey P. (1999). Yosemite National Park: A Natural History Guide to Yosemite and Its Trails. Berkeley: Wilderness Press. ↵

- Yosemite, Ibid; Cutlip, 1995, Ibid. ↵

- Lamme & Russell, 2010, Ibid., p. 351. ↵

- Mac, R. (2016, July 15). “The REAL story behind the quote ‘There’s a sucker born every minute,’” Medium, Retrieved from https://medium.com/skeptikai/the-real-story-behind-the-quote-theres-a-sucker-born-every-minute-1db9a7220d34 ↵

- Kunhardt, P.B., Kunhardt, P.B. and P.W. Kunhardt (1995). Barnum: An Illustrated Biography. New York: Knopf. ↵

- Reiss, B. (2001). The showman and the slave: Race, death, and memory in Barnum’s America. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ↵

- Wallace, I. (2023, Oct. 17). “P.T. Barnum,” Britannica, Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/P-T-Barnum ↵

- Wallace, Ibid. ↵

- Mangan, G. (2021, July 5). “P.T. Barnum: An entertaining life,” ConnecticutHistory.org. Retrieved from https://connecticuthistory.org/p-t-barnum-an-entertaining-life/ ↵

- Cook, J.W. (2001). The arts of deception: playing with fraud in the age of Barnum. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ↵

- Lamme & Russell, 2010, Ibid. ↵

- Olasky, M.N. (1985. Spring). A Reappraisal of 19th-century public relations. Public Relations Review 11, 3-12. Page 6. ↵

- Olasky, 1985, Ibid. ↵

- Piasecki, A. (2000). Blowing the railroad trumpet: Public relations on the American frontier. Public Relations Review, 26(1), 53-65. ↵

- St. John III, B. (1998). “Public Relations as community building: Then and now,” Public Relations Quarterly, 43: 34-40. ↵

- DeLorme, D. E., & Fedler. F. (2003).Journalists’ hostility toward public relations: An historical analysis. Public Relations Review, 29(4), 99-124. ↵

- At the time, “Muck” referred not to mud, but human waste. ↵

- Kruckeberg, D. and K. Starck, (1988). Public Relations and Community. New York: Praeger. ↵

- Irving Sinclair gave him this nickname following Lee’s involvement in the Colorado Coal Miner’s Strike of 1913-1914 ↵

- “The first press release,” (n.d.). News Museum. Retrieved from https://www.newsmuseum.pt/en/spin-wall/first-press-release ↵

- Hallahan, K. (2002). Ivy Lee and the Rockefellers’ response to the 1913–1914 Colorado coal strike. Journal of Public Relations Research, 14, 265–315. ↵

- Edwards, J. (2022, Sept. 1). “The dark history behind the executive to-do list,” Fortune. Retrieved from https://fortune.com/2022/09/01/dark-history-executive-to-do-list-productivity-history-jim-edwards/ ↵

- Hiebert, Ibid., p. 7. ↵

- Cutlip, S. M. (1994). The unseen power: Public relations, a history. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum Associates. Page 59. ↵

- Henry, S. (2012). Anonymous in their own names: Doris E. Fleischman, Ruth Hale, and Jane Grant. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. ↵

- Ewen, S. (1996). PR! A social history of spin. New York: Basic Books. Pages 162-163. ↵

- Cutlip, 1994, Ibid. Page 168. ↵

- Bernays, A. (1999, Dec. 31). “Doris Fleishman,” Jewish Women’s Archive. Retrieved from https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/fleischman-doris. See also Bernays, A. & J. Kaplan (2003). Back Then: Two literary lives in 1950s New York. New York: HarperCollins. ↵

- St. John III, 1998, Ibid. ↵

- Jansen, S.C. (2013). Semantic tyranny: how Edward L. Bernays stole Walter Lippmann’s mojo and got away with it and why it still matters, International Journal of Communication, 7: 1094-1111. Page 1095. ↵

- Bates, S. (2008). Selling smoke: Bernays sauce, laid on thick. The Wilson Quarterly, 32(3), 12+. https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/A181952713/AONE?u=nm_p_oweb&sid=googleScholar&xid=665416bf ↵

- Murphree, V. (2015). Edward Bernays’s 1929 ‘Torches of Freedom’ March: Myths and Historical Significance, American Journalism, 32(3): 258-281. ↵

- Bates, Ibid. ↵

- Bernays, E.L. (1923). Crystallizing Public Opinion. Ig Publishing: New York. Page 200. ↵

- Jansen, Ibid., p. 1098. ↵

- Bivins, T.H. (2013). A golden opportunity? Edward Bernays and the dilemma of ethics. American Journalism, 30(4): 496-519. ↵

- Brown, L. (2017, June 1). “A Chiquita PR campaign powerful enough to topple the Guatemalan government,” Modern Marketing Partners. Retrieved from https://www.modernmarketingpartners.com/2017/06/01/chiquita-pr-campaign/ ↵

- Schlesinger, S., & Kinzer, S. (2020). Bitter fruit: The story of the American coup in Guatemala, revised and expanded. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ↵

- Tye, L. (2006). “Watch out for the top banana,” Cabinet, 23. Retrieved from https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/23/tye.php ↵

- Myers, M.B. (1995). “The United Fruit Company in Central America: History of a public relations failure,” 7th Marketing History Conference Proceedings, Vol. VII, pp. 251-258. ↵

- Jardin, X. (2007, Jan. 29). “Group works to identify remains in Guatemala,” NPR. Retrieved from: https://www.npr.org/2007/01/29/7019560/group-works-to-identify-remains-in-guatemala ↵

- Tye, 2006, Ibid. ↵

- Dufty, W., & Lefevere, A. (1975). Sugar blues (p. 256). Chilton Book Company. ↵

- Kearns, C.E., Glantz, S.A. & Apollonio, D.E. (2019). In defense of sugar: a critical analysis of rhetorical strategies used in The Sugar Association’s award-winning 1976 public relations campaign. BMC Public Health 19, 1150. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7401-1 ↵

- Courtwright 1, D. T. (2005). ‘Carry on smoking’: Public relations and advertising strategies of American and British tobacco companies since 1950. Business History, 47(3), 421-433. Page 430. ↵

- Beder, S. (2002). Environmentalists help manage corporate reputation: changing perceptions not behaviour. See also Oreskes, N. and Conway, E. (2011). Merchants of Doubt, New York, NY: Bloomsbury Press. ↵

- Variants of this quote, some substituting “life” for “history” have been attributed to individuals ranging from Elbert Hubbard and Mark Twain to Winston Churchill. ↵

- For the Civil Rights Movement, see Straughan, D.M. (2004). “’Lift every voice and sing,’: the public relations efforts of the NAACP, 1960-1965” Public Relations Review, 30(1): 49-60. ↵

- For the Gay Rights movement, see Alwood, E. (2015). “The role of public relations in the gay rights movement, 1950-1969” Journalism History, 41(1): 11-20. ↵

- Garrow, D.J. (1986). Bearing the cross: Martin Luther King, Jr., and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. New York: Random House. Cited in Hon, L.C. (1997). “To redeem the soul of America”: Public Relations and the Civil Rights Movement, Journal of Public Relations Research, 9(3): 163-212. Page 163. ↵

- Watson, T. (2012). The evolution of public relations measurement and evaluation. Public relations review, 38(3), 390-398. ↵

- Grunig, J.E. (1983). Basic research provides knowledge that makes evaluation possible, Public Relations Quarterly, 28 (3), pp. 28-32. ↵

- Watson, 2012, Ibid. ↵

- Falkheimer, J. & Heide, M. (2018). Strategic Communication: An Introduction. Routledge: New York. ↵

- Solis, B. (2009). The state of PR, Marketing and Communications: You are the future. briansolis.com (blog), June 8, 2009. Retrieved from http://www.briansolis.com/2009/06/state-of-pr-marketing-and/ ↵

- Falkheimer & Heide, 2018, Ibid., p. 88. ↵

- In Crystallizing Public Opinion, Bernays describes a PR practitioner as someone who “…interprets the client to the public, which [they] are enabled to do in part because [they interpret] the public to the client.” (p. 51). Bernays again uses that description, further clarifying that they also help “…to mould the action of [their] client as well as to mould public opinion,” adding that the “profession is in a state of evolution” (p. 82). ↵

- Bivins, 2013, Ibid. ↵

- Hiebert, Ibid., p. 11. ↵

- Lamme & Russell, 2010, Ibid., p. 354. ↵

- Hiebert, Ibid., p. 9. ↵