9 Roots of American National Culture

Nolan Weil

Suggested Focus

This chapter is a crash course in American history from the perspective of social history and cultural geography. If you can grasp the argument of this chapter, you might begin to see American culture in a completely new light.

- Name from memory as many as you can of the American beliefs and values discussed at the beginning of the chapter.

- What does Woodard mean when he says there are 11 nations in North America? (What is a nation?)

- Besides the English, which three other European powers established a major presence in North America?

- What makes New York the unique city that it is?

- To which colonies does Albion’s Seed refer? From where did these colonists come exactly? How was the understanding of “freedom” different in each of those colonies?

- From where did the founders of the Deep South come?

- What happened during the Westward Expansion?

Preliminary remarks

The title of this chapter, The Roots of American Culture, may require a bit of explaining; otherwise perhaps it may not be apparent how the two parts of the chapter fit together. Where does one look for the roots of a national culture? This chapter suggests looking in two places. On one hand, we might suppose those roots might be exposed if we simply examine the beliefs and values that seem to animate the culture as it lies before us in the present. This then is how we begin this chapter on American national culture, with a snapshot of American beliefs and values that have been repeatedly identified by observers of the American scene.

On the other hand, we suggest, perhaps this view is too superficial, painting American culture in an overly generalized, stereotypical way. We point out that there is too much strife and political division in the United States to suppose that the national culture can be so easily captured. In fact, we question whether there is a “national culture” at all and suggest that if we look at the founding and settlement of the United States in historical perspective, as we do throughout the remainder of the chapter, we see not one national culture but many regional cultures. And while an overwhelming majority of Americans may say they hold dearly the value of “freedom,” if we look closely, we begin to see that not all Americans understand freedom in the same way. Once we realize this, we may be better able to understand the obvious divisions in contemporary American society.

American beliefs and values

As pointed out in the last chapter, it is a mistake to automatically assume that everyone in a large multicultural country like the U.S. shares a common culture. But this hasn’t stopped many writers from suggesting that they do. Among the most recent popular essays to address the question of American beliefs and values is Gary Althen’s “American Values and Assumptions.” Here is a list of the beliefs and values that Althen (2003) identifies as typically American:

- individualism, freedom, competitiveness and privacy

- equality

- informality

- the future, change and progress

- the goodness of humanity

- time

- achievement, action, work and materialism

- directness and assertiveness

In what follows, I summarize Althen’s description of typical American values and assumptions, sometimes extending his examples with my own.

Individualism

According to Althen (2003), “the most important thing to understand about Americans is probably their devotion to individualism. They are trained from very early in their lives to consider themselves as separate individuals who are responsible for their own situations . . . and . . . destinies. They’re not trained to see themselves as members of a close-knit interdependent family, religious group, tribe, nation, or any other collectivity.”

Althen illustrates the above point by describing an interaction he observed between a three-year-old boy and his mother. They are at the mall, and the boy wants to know if he can have an Orange Julius, (a kind of cold drink made from orange juice and ice). The mother explains to him that he doesn’t have enough money for an Orange Julius because he bought a cookie earlier. He has enough for a hot dog. Either he can have a hot dog now, she says, or he can save his money and come back another day to buy an Orange Julius.

Althen says that people from other countries often have a hard time believing the story. They wonder, not just why such a young child would have his own money, but how anyone could reasonably expect a three-year-old to make the kind of decision his mother has suggested. But Americans, he says, understand perfectly. They know that such decisions are beyond the abilities of three-year-olds, but they see the mother as simply introducing the boy to an American cultural ideal—that of making one’s own decisions and being responsible for the consequences.

Freedom

Americans feel strongly about their freedom as individuals. They don’t want the government or other authorities meddling in their personal affairs or telling them what they can and cannot do. One consequence of this respect for the individuality of persons, Althen claims is that Americans tend not to show the kind of deference to parents that people in more family-oriented societies do. For example, Americans think that parents should not interfere in their children’s choices regarding such things as marriage partners or careers. This doesn’t mean that children do not consider the advice of parents; quite the contrary, psychologists find that American children generally embrace the same general values as their parents and respect their opinions. It is just that Americans strongly believe everyone should be free to choose the life he/she wishes to live.

Competitiveness

The strong emphasis on individualism pushes Americans to be highly competitive. Althen sees this reflected not only in the American enthusiasm for athletic events and sports heroes, who are praised for being “real competitors,” but also in the competitiveness that pervades schools and extracurricular activities. According to Althen, Americans are continually making social comparison aimed at determining:

. . . who is faster, smarter, richer, better looking; whose children are the most successful; whose husband is the best provider or the best cook or the best lover; which salesperson sold the most during the past quarter; who earned his first million dollars at the earliest age; and so on.

Privacy

Americans assign great value to personal privacy, says Althen, assuming that everyone needs time alone to reflect or replenish his or her psychic energy. Althen claims that Americans don’t understand people who think they always have to be in the company of others. He thinks foreigners are often puzzled by the invisible boundaries that seem to surround American homes, yards, and offices, which seem open and inviting but in fact are not. Privacy in the home is facilitated by the tendency of American houses to be quite large. Even young children may have bedrooms of their own over which they are given exclusive control.

Equality

The American Declaration of Independence asserted (among other things) that “all men are created equal.” Perhaps most Americans are aware that equality is an ideal rather than a fully realized state of affairs; nevertheless, says Althen, most Americans “have a deep faith that in some fundamental way all people . . . are of equal value, that no one is born superior to anyone else.”

Informality

American social behavior is marked by extraordinary informality. Althen sees this reflected in the tendency of Americans to move quickly, after introductions, to the use of first names rather than titles (like Mr. or Mrs.) with family names. Americans, says Althen, typically interact in casual and friendly ways. Informality is also reflected in speech; formal speech is generally reserved for public events and only the most ceremonious of occasions. Similarly, Americans are fond of casual dress. Even in the business world, where formal attire is the rule, certain meetings or days of the week may be designated as “business casual,” when it is acceptable to shed ties, suit coats, skirts and blazers. Foreigners encountering American informality for the first time may decide that Americans are crude, rude, and disrespectful.

The Future, Change, and Progress

The United States is a relatively young country. Although the first European colonies appeared in North America nearly 400 years ago, the United States is only 240 years old as I write these words. Perhaps this is why the U.S. tends to seem less tied to the past and more oriented towards the future. Moreover, the country has changed dramatically since the time of its founding, becoming a major world power only in the last 75 years.

To most Americans, science, technology and innovation are more salient than history and tradition, says Althen. Americans tend to regard change as good, and the new as an improvement over the old. In other words, change is an indication of progress. Americans also tend to believe that every problem has a solution, and they are, according to Althen, “impatient with people they see as passively accepting conditions that are less than desirable.”

The Goodness of Humanity

Although some Americans belong to religious groups that emphasize the inherent sinfulness of man, Althen claims that the basic American attitude is more optimistic. For one thing, the American belief in progress and a better future, Althen argues, would not be possible if Americans did not believe human nature was basically good, or at least that people have it within their power to improve themselves. The robust commercial literature of self-help or self-improvement is another source of evidence for this conviction.

Time

Americans regard time as a precious resource, says Althen. They believe time should always be used wisely and never wasted. Americans are obsessed with efficiency, or getting the best possible results with the least expenditure of resources, including time.

Achievement, Action, Work, and Materialism

American society is action oriented. Contemplation and reflection are not valued much unless they contribute to improved performance. Americans admire hard work, but especially hard work that results in substantial achievement. “Americans tend to define and evaluate people,” says Althen, “by the jobs they have.” On the other hand, “family backgrounds, educational attainments, and other characteristics are considered less important.”

Americans have also been thought of as particularly materialistic people, and there is no denying that American society is driven by a kind of consumer mania. Material consumption is widely seen as the legitimate reward for hard work.

Directness and Assertiveness

Americans have a reputation for being direct in their communication. They feel people should express their opinions explicitly and frankly. As Althen expresses it, “Americans usually assume that conflicts or disagreements are best settled by means of forthright discussions among the people involved. If I dislike something you are doing, I should tell you about it directly so you will know, clearly and from me personally, how I feel about it.”

Assertiveness extends the idea of directness in the expression of opinion to the realm of action. Many Americans are raised to insist upon their rights, especially if they feel they have been treated unfairly, or cheated, e.g., in a business transaction. There is a strong tradition, for example, of returning merchandise to retail stores, not only if it is defective but even if it just does not live up to an individual’s expectation as a customer. The retailer who refuses to satisfy a customer’s demand to refund the cost of an unacceptable product is likely to face a stiff argument from an assertive or even angry customer. The customer service personnel of major retailers tend, therefore, to be quite deferential to customer demands.

Conclusion

In his discussions of American values and assumptions, Althen is careful to point out that generalizations can be risky—that it would be a mistake to think that all Americans hold exactly the same beliefs, or even that when Americans do agree, that they do so with the same degree of conviction. He is also careful to note that the generalizations represent the predominant views of white, middle class people who have for a long time held a majority of the country’s positions in business, education, science and industry, politics, journalism, and literature. He acknowledges that the attitudes of many of the nation’s various ethnic minorities might differ from the values of the “dominant” culture but insists that as long as we recognize these limitations, it is reasonable to regard the observations he offers as true on the average.

There may be a good deal of truth to Althen’s claim; however, a closer look into American history reveals considerable regional variation in Americans’ understanding of even the most fundamental ideals, e.g., ideas about the freedom of the individual. In Part 2, we will see that a closer look at the American political scene, may force us to conclude that even when Americans endorse the same values, they may actually have different things in mind.

A closer look at American cultural diversity

In this section, I want to show why the idea of a dominant American culture is more complicated than it is often taken to be. Listen to any serious political commentary on American TV and sooner or later you will hear about the radical polarization of American culture and politics. Commentators may differ on whether we have always been this way, or whether it is worse than ever, but journalists and scholars alike are nearly unanimous in insisting that the country is anything but unified. Every U.S. President at the annual State of the Union Address says we are unified, but that is something the President must say. “The state of our Union is strong,” are the words traditionally uttered. But does anyone believe it?

And just when many of us think we have finally put the American Civil War and the shameful legacy of slavery behind us once and for all by electing the first black president, the nation turns around and elects a successor that surely has Abraham Lincoln turning over in his grave. How is it possible? Essays like Althen’s certainly do not give us any clue.

What could possibly explain it?

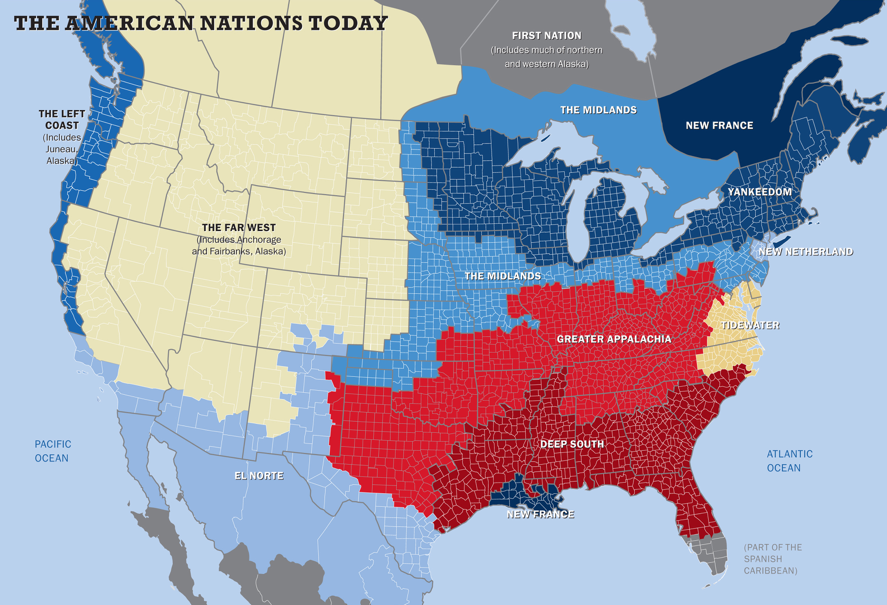

Perhaps we can find a clue in the work of cultural geographers, historians, and journalists. Back to the original question: Is there really a dominant American culture? Depending upon whom you read, there is not one unified American culture. Rather, at least four cultures sprang from British roots, and altogether there may be as many as eleven national cultures in the U.S. today. (See Figure 8.1)

Understanding U.S. Cultural Landscapes

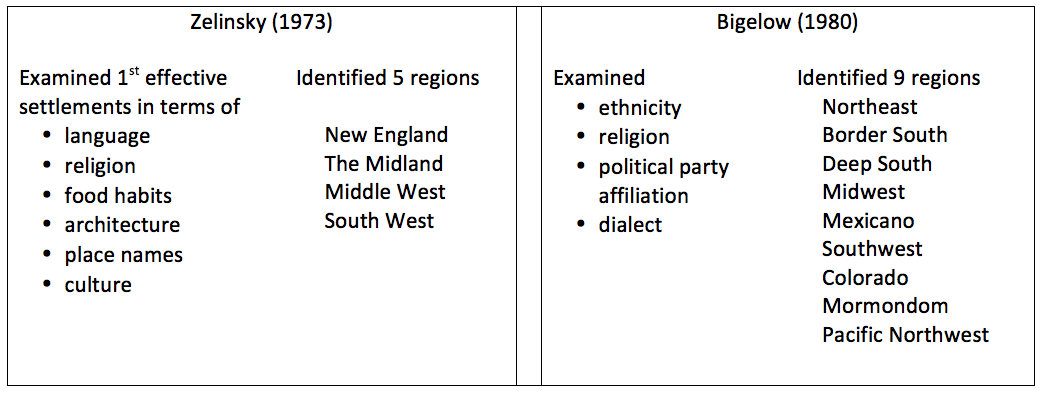

In 1831, 26-year old French aristocrat Alexis de Tocqueville toured the United States. Four years later, he published the first of two volumes of Democracy in America. At that time, Tocqueville saw the United States as composed of almost separate nations (Jandt, 2016). Since then, cultural geographers have produced evidence to support many of Tocqueville’s observations, noting that as various cultural groups arrived in North America, they tended to settle where their own people had already settled. As a result, different regions of the U.S. came to exhibit distinctive regional cultures. Zelinsky (1973) identified five distinctive cultural regions while Bigelow (1980) identified no fewer than nine. (See Table 8.1)

Joel Garreau (1981), while an editor for the Washington Post, also wrote a book proclaiming that the North American continent is actually home to nine nations. Based on the observations of hundreds of observers of the American scene, Garreau begins The Nine Nations of North America by urging his readers to forget everything they learned in sixth-grade geography about the borders separating the U.S., Canada, and Mexico, as well as all the state and provincial boundaries within. Says Garreau:

Consider, instead, the way North America really works. It is Nine Nations. Each has its capital and its distinctive web of power and influence. A few are allies, but many are adversaries. Some are close to being raw frontiers; others have four centuries of history. Each has a peculiar economy; each commands a certain emotional allegiance from its citizens. These nations look different, feel different, and sound different from each other, and few of their boundaries match the political lines drawn on current maps. Some are clearly divided topographically by mountains, deserts, and rivers. Others are separated by architecture, music, language, and ways of making a living. Each nation has its own list of desires. Each nation knows how it plans to get what it needs from whoever’s got it. …Most important, each nation has a distinct prism through which it views the world. (Garreau, 1981: 1-2)

Historian David Hackett Fischer (1989) has argued that U.S. culture is best understood as an uneasy coexistence of just four original core cultures derived from four British folkways, each hailing from a different region of 17th century England. Most recently, journalist Colin Woodard (2011) drawing on the work of Fischer and others has identified eleven North American nations. In the sections that follow, I hope to show why essays like Althen’s may not be helpful for understanding American culture. In the process, I will briefly recount the story of the settling of North America for those who may not be entirely aware of that history.

Officially, of course, only three countries, Canada, the United States, and Mexico, occupy the entirety of North America, and each country began as a European project. The principal powers driving the settlement of the continent were England, France, and Spain. All three powers had a major presence in parts of what is now the United States before the U.S. assumed its present shape.

Spanish influence

Spain was the first European power to insert itself into the Americas, starting in the Caribbean islands after the arrival of Christopher Columbus in 1492. Spain would eventually dominate most of South America and Mexico and even gain a temporary foothold in present day Florida as well as much of the American Southwest and California.

By the time the first Englishmen stepped off the boat at Jamestown . . . Spanish explorers had already trekked through the plains of Kansas, beheld the Great Smoky Mountains of Tennessee, and stood at the rim of the Grand Canyon. They had mapped the coast of Oregon . . . [and] established short-lived colonies on the shores of Georgia and Virginia. In 1565, they founded St. Augustine, Florida, now the oldest European city in the United States. By the end of the sixteenth century, Spaniards had been living in the deserts of Sonora and Chihuahua for decades, and their colony of New Mexico was marking its fifth birthday. (Woodard, 2011: 23)

The descendants of the first Spanish settlers in the Southwest (many of whom intermarried with the indigenous peoples) thought of this region as el Norte (the north), and while Spanish influence on the West would eventually be eclipsed by English folkways, Spanish influences persist to this day.

French influence

While the Spanish spread out across the South and laid claim to the West, the French dropped in from the North. Frenchmen explored the coasts of Newfoundland and sailed up the Saint Lawrence River in 1534. They sailed the coasts of New Brunswick and Maine and established the first successful French settlement in Nova Scotia in 1605, followed by Quebec City in 1608 and Montreal in 1642. From Montreal, the St. Lawrence River carried them to the Great Lakes and from there by way of an extensive network of rivers into the vast interior of the continent, the so-called Louisiana territory. Following the great Mississippi River down to the Gulf of Mexico, the French founded New Orleans in 1718.

Moreover, the French established a more sympathetic and human relationship with the native peoples than either the Spanish or the English had. As Woodard (2011) has observed, the Spanish enslaved the Indians; the English drove them out; but the French settled near them, learned their customs and established trading alliances “based on honesty, fair dealing, and mutual respect” (p. 35)

The legacy of New France, as it was called, can still be felt in isolated pockets of the U.S., like southern Louisiana and the city of New Orleans, and also near the northern boundaries of eastern states like Vermont and Maine. Otherwise, it has a stronger pull on Canada where it continues to resist domination by the English-speaking regions of Canada. On the other hand, Spanish influences are more widely felt in the United States, particularly in South Florida and throughout the southwestern U.S. and California. However, the dominant culture of the United States—or as Fischer (1989) has argued—the four dominant cultures are British.

Dutch influence

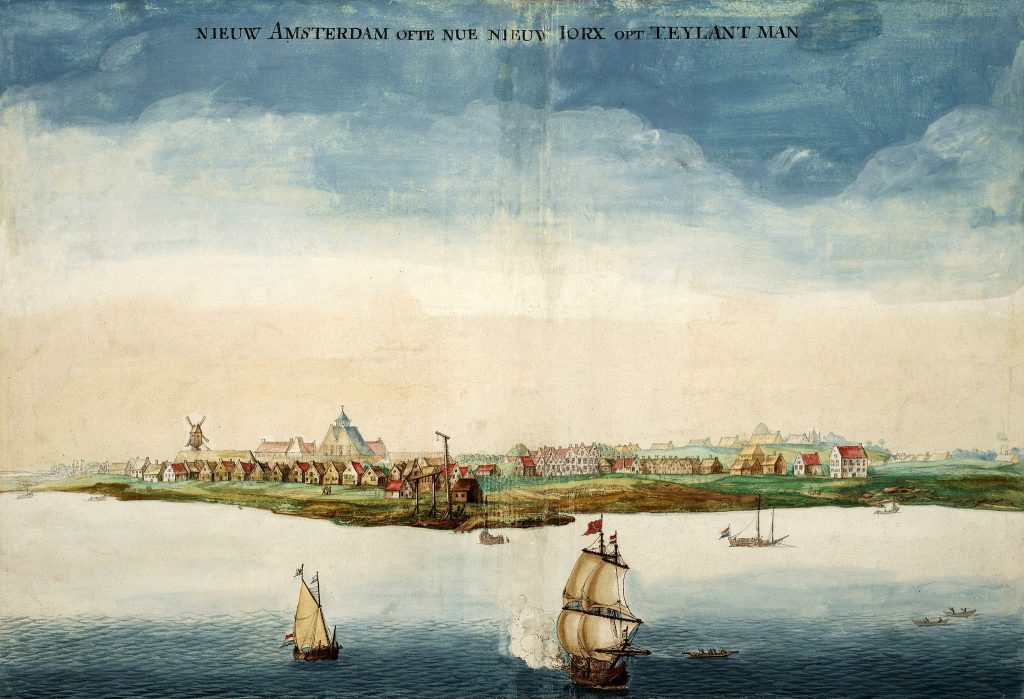

Another European power to establish a presence in North America was the Netherlands. In 1624, the Dutch established a fur trading post on what is today the Island of Manhattan in New York City. In fact, Woodard (2011: 65) reminds us, the character of New York City is due very much to the cultural imprint of the first Dutch settlers of New York. Of course, it was not called New York back then but New Amsterdam.

Unlike the Puritans who would come five years later, the Dutch had no interest in creating a model society. Nor were they interested in establishing democratic government. During the first few decades of its existence, New Amsterdam was formally governed by the Dutch West India Company, one of the first global corporations. The Dutch were interested in North America primarily for commercial purposes.

To understand how the Dutch influenced New York, it is important to understand the culture and social history of the Netherlands. By the end of the 1500’s, the Dutch had waged a successful war of independence against a huge monarchical empire (the kingdom of Spain). They had asserted the inborn human right to rebel against an oppressive government, and they had established a kingless republic nearly two centuries before the American Revolution, which established American independence from the British Empire.

“In the early 1600s, the Netherlands was the most modern and sophisticated country on Earth,” says Woodard (2011: 66-67). They were committed to free inquiry. Their universities were among the best in the world. Scientists and intellectuals from countries where free inquiry was suppressed flocked to the Netherlands and produced revolutionary scientific and philosophical texts. Dutch acceptance of freedom of the press resulted in the wide distribution of texts that were banned elsewhere in Europe. The Dutch asserted the right of freedom from persecution for the free exercise of religion. They produced magnificent works of art and established laws and business practices that set the standard for the Western world. They invented modern banking, establishing the first clearinghouse at the Bank of Amsterdam for the exchange of the world’s currencies.

The Dutch had also virtually invented the global corporation with the establishment of the Dutch East India Company in 1602. With 10,000 ships of advanced design, shareholders from all social classes, thousands of workers, and global operations, the Netherlands dominated shipping in northern Europe in the early 1600s.

By the time the Dutch West India Company founded New Amsterdam, the Netherlands had assumed a role in the world economy equivalent to that of the United States in the late 20th century, setting the standards for international business, finance, and law. (Woodard, 2011: 67)

The Dutch effectively transplanted all of these cultural achievements to New Amsterdam. Dutch openness and tolerance consequently attracted a remarkable diversity of people. The ethnic, linguistic, and religious diversity, says Woodard, shocked early visitors. The streets of New Amsterdam teamed with people from everywhere, just as New York does today.

By the mid 1600’s, there were “French-speaking Walloons; Lutherans from Poland, Finland; and Sweden; Catholics from Ireland and Portugal; and Anglicans, Puritans, and Quakers from New England. . . [D]ozens of Ashkenazim [eastern European Jews] and Spanish-speaking Sephardim [Jews from Spain] settled in New Amsterdam in the 1650s, forming the nucleus of what would eventually become the largest Jewish community in the world. Indians roamed the streets, and Africans—slave, free and half-free—already formed a fifth of the population. A Muslim from Morocco had been farming outside the city walls for three decades. (Woodard, 2011: 66)

When the Duke of York, future King James II of England, arrived with a naval fleet in 1664, the Dutch were forced to cede political control of New Amsterdam to England. New Amsterdam became New York. However, the Dutch managed to negotiate terms, which enabled them to maintain a presence and preserve Dutch norms and values. Thus, diversity, tolerance, upward mobility, and the emphasis on private enterprise, characteristics historically associated with the United States in general and New York in particular, began in New Amsterdam and represent the Dutch legacy in America.

Albion’s Seed

Of the three major European powers, the English were latecomers. But when they finally came, they washed over the continent like a tsunami. Today English cultural influences prevail over vast areas of both Canada and the United States.

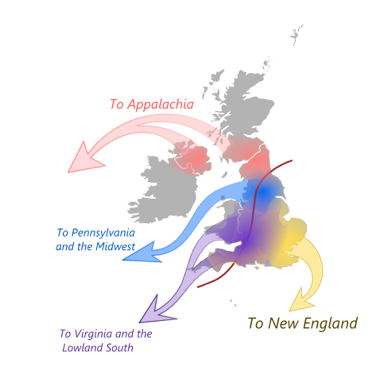

In his book, Albion’s Seed, David Fischer argues that the foundations of U.S. culture were laid between 1629-1775 by four great waves of English-speaking immigrants. Each wave brought a group of people from a different region of England, and each group settled in a different region of British America.

- The first wave (1629-1640) brought Puritans from the East of England to Massachusetts.

- The second wave (1642-1675) brought a small Royalist elite and large numbers of indentured servants from the South of England to Virginia.

- The third wave (1675-1725) consisted of people from the North Midlands of England and Wales. This group settled primarily in the Delaware Valley.

- Finally, multiple waves of people arrived between 1718-1775 from the borders of North Britain and Ireland. Most of these people settled in the mountains of the Appalachian backcountry.

According to Fischer, despite all being English-speaking Protestants living under British laws and enjoying certain British “liberties,” each group came from a different geographical region, and each region had its own particular social, political, and economic circumstances. As a result, the basic attitudes, behaviors, and values of each group were profoundly different.

Massachusetts (Yankeedom)

The Puritans who founded Massachusetts Bay Colony were not the first English settlers in New England; the so-called Pilgrims beat them by about 10 years. But the Massachusetts Bay Puritans left a more lasting legacy. The Puritans came in greater numbers over an eleven-year period (1629-1640), primarily from East Anglia. In the 17th century, East Anglia was the most economically developed area of Britain. East Anglians were artisans, farmers, and skilled craftsmen; they were well educated and literate. They had little respect for royal or aristocratic privilege. In East Anglia, they had practiced local self-government by means of elected representatives (selectmen) whom they trusted to carry out the affairs of the community. They were middle class and roughly all equal in material wealth.

When they migrated to Massachusetts, they brought with them their own particular folkways. These included many of the customs and values they had been accustomed to in East Anglia. They were also deeply religious and brought a utopian vision of a society that would bring about God’s kingdom on earth, governed by a particular Puritan interpretation of the Bible. They only accepted people into their communities that were willing to conform to their Puritan brand of Calvinism; dissenters were punished or exiled.

On the other hand, according to Boorstin (1958), the Puritans were completely non- utopian and practical in the way they lived their daily lives. Because they considered their theological questions answered, says Boorstin, they could focus less on the ends of society and more on the practical means for making society work effectively. Eventually, historical circumstances would even sweep the religious authoritarianism away, leaving behind a legacy self-government, local control, and direct democracy.

As Woodard (2011) has observed, “Yankees would come to have faith in government to a degree incomprehensible to people of the other American nations.” New Englanders trusted government to defend the public good against the selfish schemes of moneyed interests. They were in favor of promoting morality by prohibiting and regulating undesirable activities. They believed in the value of public spending on infrastructure and schools as a means for creating a better society. Today, notes Woodard, “More than any other group in America, Yankees conceive of government as being run by and for themselves.” They believe everyone should participate, and nothing makes them angrier than the manipulation of the political process for private gain (p. 60).

Virginia (Tidewater)

According to Fischer (1989) as the Puritan migrations were coming to an end in 1641, a new migration was just about to begin. This migration was from the south of England, and these newcomers settled in what is today southeast Virginia, in the area known as the Tidewater. The founders of Virginia were about as different from the New England Puritans as any group could be.

While the Puritans were artisans, farmers, and craftsmen from the east of England, the Tidewater Virginians had been English “gentlemen” in south England. The economy of south England in 17th century was organized mainly around the production of grain and wool. While the Puritans enjoyed a fairly egalitarian life in East Anglia, the south of England was marked by severe economic inequality. Those who didn’t own land were tenants. The region had also suffered greatly during the English Civil War, a conflict that pitted the King of England against the Parliament over the manner in which England was to be governed. The landed gentry of south England were Royalists; they supported the King. However, they found themselves on the losing side of the conflict. Unlike the Puritans who migrated to New England for religious reasons, the Royalists hoped to escape their deteriorating situation by seeking their fortunes in the New World. To the extent that religion was important to them, they embraced the Anglican Church of England, the same church as the King of England.

Like the Puritans, the Royalists were not the first English settlers in their respective region. The earliest Virginians had founded the Jamestown Colony in 1607. Also, like the Puritans, the Royalists turned out to be more successful administrators than the settlers who had come before. But while the Jamestown settlers had been incompetent in many ways, they had set the stage for a successful agricultural export industry based on tobacco (Woodard, 2011).

Tobacco was a very lucrative crop and Virginia was perfect for growing it, but it was very labor-intensive. The Virginians solved their labor problem by recruiting a large workforce of desperate people from London, Bristol, and Liverpool. In fact, poor newcomers greatly outnumbered the Royalist elites; more than 75 percent of immigrants to Virginia came as indentured servants. Two thirds were unskilled laborers and most could not read or write. The Royalists, in fact, succeeded in reproducing the conditions that had existed in the south of England where they had been the lords and masters of large estates, exploiting a vast and permanent underclass of poor, uneducated Englishmen. Even worse, when the Virginians began losing their workforce because the servants completed their indentures, they turned to slave labor, which would eventually spread across the entire southern United States. Before the abolition of slavery in 1865, millions of Africans would be kidnapped and shipped to the New World (and later bred In America) as permanent property (Woodard, 2011).

As Fischer (1989) has pointed out, people everywhere in British America embraced the ideal of liberty (freedom) in one form or another; however, it would be a mistake to think that liberty had the same meaning to New Englanders as it did to Virginians. New Englanders believed in ordered liberty, which meant that liberty belonged not just to an individual but to an entire community. In other words, an individual’s liberties or rights were not absolute but had to be balanced against the public good. New Englanders voluntarily agreed to accept constraints upon their liberties as long as they were consistent with written laws and as long as it was they themselves that collectively determined the laws. It is also true though that because the original Puritan founders saw themselves as God’s chosen people, they did not at first feel compelled to extend freedom to anyone outside of their Puritan communities.

The Virginians, in contrast, embraced a form of liberty that Fischer has described as hegemonic or hierarchical liberty. According to Fischer (1989) freedom for the Virginian was conceived as “the power to rule, and not to be overruled by others. . . . It never occurred to most Virginia gentlemen that liberty belonged to everyone” (pp. 411-412). Moreover, the higher one’s status, the greater one’s liberties. While New Englanders governed themselves by mutual agreement arrived at in town hall meetings, Virginian society was ruled from the top by a small group of wealthy plantation owners who completely dominated the economic and political affairs of the colony.

Delaware Valley (The Midlands)

The third major wave of English immigration took place between 1675-1725 and originated from many different parts of England, but one region in particular stood out—the North Midlands, a rocky and sparsely settled region inhabited by farmers and shepherds. The people had descended from Viking invaders who had colonized the region in the Middle Ages. They favored the Norse customs of individual ownership of houses and fields and resented the imposition of the Norman system of feudal manors, which the southern Royalists had embraced (p.446). The most peculiar thing about the people was their religion. They were neither Puritans like the people of eastern England, nor Anglican like the Royalists of the south, but Quaker, or as they called themselves Friends.

The Quakers began arriving in great numbers in 1675, settling in the Delaware Valley, spreading out into what is today western New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania. Sandwiched between Puritan Massachusetts and Royalist Virginia, Woodward (2011) refers to this region as the Midlands.

By 1750, the Quakers had become the third largest religious group in the British colonies (Fischer, p. 422). Like the Puritans and unlike the Royalists, the Quakers sought to establish a model society based on deeply held religious beliefs. But whereas the Puritans tended restrict the liberties of outsiders, even persecuting them, the Quakers (under the leadership of William Penn) “envisioned a country where people of different creeds and ethnic backgrounds could live together in harmony” (Woodard, p. 94). The Quakers would not impose their religion on anyone but would invite everyone into the community who accepted their worldview. They extended the right to vote to almost anyone and provided land on cheap terms. They maintained peace with the local Indians, paid them for their land, and respected their interests.

Quakers held government to be an absolute necessity and were intensely committed to public debate. At the same time, they developed a tradition of minimal government interference in the lives of people. The Quaker view of liberty was different from that of both the Puritans and the Royalists. While the Puritans embraced ordered or bounded liberty for God’s chosen few, and the Royalists embraced a hierarchical view of liberty for the privileged elite (and who saw no contradiction in the keeping of slaves), the Quakers believed in reciprocal liberty, a liberty that they believed should embrace all of humanity. The Quakers were the most egalitarian of the three colonies discussed so far, and they would be among the most outspoken opponents of slavery.

Appalachia

The last great waves of folk migration came between 1718-1775 from the so-called borderlands of the British Empire, Ireland, Scotland, and the northern counties of England. They were a clan-based warrior people whose ancestors had endured 800 years of almost constant warfare with England (Woodard, p. 101). Unlike the Puritans or the Quakers who dreamed of establishing model societies based upon their religious beliefs, or the Royalists who wished to regain their aristocratic wealth and privilege, the Borderlanders sought to escape from economic privation: high rents, low wages, heavy taxation, famine and starvation.

These new immigrants landed on American shores primarily by means of Philadelphia and New Castle in the Quaker Midlands, mainly because of the Quaker policy of welcoming immigrants. Unfortunately, the Borderlanders, proved too belligerent and violent for the peace-loving Quakers, who tried to get them out of their towns and into the Appalachian backcountry as quickly as possible. The Appalachian Mountains extend for 800 miles from Pennsylvania to Georgia and several hundred miles east to west from the Piedmont Plateau to the Mississippi. The Borderlanders would end up spreading their folkways throughout this vast region.

While the other three colonial regions established commercial enterprises revolving around cash groups and manufactured goods, the Borderlanders lived primarily by hunting, fishing, and farming. In Britain, they had never been accustomed to investing in fixed property because it was too easily lost in war. In the American backcountry, they carried on in the same way; whatever wealth they had was largely mobile, consisting of herds of pigs, cattle, and sheep. They practiced slash-and-burn agriculture, moving to new lands every few years when they had depleted the soil in one place. In time, some individuals managed to acquire large tracts of land, while others remained landless. The result was to reproduce the pervasive inequality that had existed in the northern English borderlands.

Early on, Appalachia acquired a reputation as a violent and lawless place. In the earliest years of settlement, there was little in the way of government. To the extent that there was any order or justice, it was according to the principle lex talionis, which held that “a good man must seek to do right in the world, but when wrong was done to him, he must punish the wrongdoer himself by an act of retribution. . .” (Fischer, p. 765).

The people that settled Appalachia held to an ideal of liberty that Fischer has called “natural liberty,” characterized by a fierce resistance to any form of external restraint and “strenuously hostile to ordering institutions” (Fischer, p. 777). This included hostility to organized churches and established clergy. The Appalachian backcountry was a place of mixed religious denominations, just as the borders of North Britain had been. However, if there was a dominant denomination, it may have been Scottish Presbyterianism.

In essence, the Borderlanders reproduced many aspects of the society they had left behind in the British borderlands, a society marked by economic inequality, a culture of violence and retributive justice, jealous protection of individual liberty, and distrust of government. A more different culture from that of New England or the Midlands is hard to imagine. Except perhaps for the Deep South.

Englanders from Barbados

The Deep South

Fischer does not deal with the founders of the Deep South in Albion’s Seed for the simple reason that none of them came directly from England as the Puritans, Virginians, Quakers, and Borderlanders had. Instead, they were in Woodard’s words “the sons and grandsons of the founders of an older English colony: Barbados, the richest and most horrifying society in the English-speaking world” (p. 82). The colonizers of Barbados had established a wealthy and powerful plantation economy based on sugar cane, grown entirely by means of a brutal system of slave labor. Having run out of land on Barbados, it became necessary for Barbadians to find new lands, which they did by migrating to other islands in the Caribbean and to the east coast of North America.

The Barbadians arrived near present day Charleston, South Carolina in 1670 and set to work replicating a slave state almost identical to the one they had left behind in Barbados. They bought enslaved Africans by the boatloads and put them to work growing rice and indigo for export to England. They often worked them to death just as they had in Barbados. They built a tremendous amount of wealth from this slave labor, and most of it was concentrated in the hands of a few ruling families who comprised only about one quarter of the white population. They governed the territory solely to serve their own interests, ignoring the bottom three-quarters of the white population, and of course the black majority who actually made up 80 percent of the population. The brutality of the system is certainly shocking to modern sensibilities, and it was even shocking to the Barbadian’s contemporaries.

While slavery was initially tolerated in all of the colonies, it was an organizing economic principle only in the Tidewater region and the Deep South. However, there were important differences. Initially, the Tidewater leaders had imported labor in the form of indentured servants both white and black. Indentured servants could earn their freedom, and many blacks did. In the Tidewater, slaves outnumbered whites by only 1.7 to 1, and the slave population grew naturally after 1740, eliminating the need to import slaves. And because there were few newcomers, the black population of the Tidewater was “relatively homogenous and strongly influenced by the English culture it was embedded within” (Woodard, p. 87). Having African heritage did not necessarily make someone a slave in the Tidewater. People in the Tidewater found it harder to deny the humanity of black people.

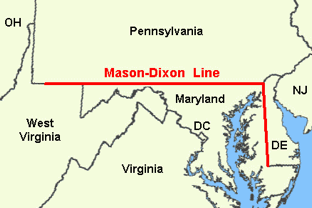

In the Deep South, however, the black population outnumbered the white population by about 5 to 1, and blacks lived largely apart from whites. Moreover, the separation of whites and blacks was strictly enforced, and the white minority thought of blacks as inherently inferior. Because they were so greatly outnumbered, Southern plantation owners also feared the possibility of a violent rebellion, and they organized militias and conducted training exercises in case they might need to respond to an uprising. “Deep Southern society,” says Woodard, “was not only militarized, caste-structured, and deferential to authority, it was also aggressively expansionist” (p. 90). Unfortunately, the slaveholding practices of the Deep South eventually caught hold in the Tidewater too. By the middle of the 18th century, permanent slavery came to be the norm everywhere south of the Mason-Dixon line.

The Westward Expansion

After the American Revolution, four of the nations that we have just surveyed headed west: New England, the Midlands, Appalachia, and the Deep South all raced towards the interior of the continent apparently with little mixing. Figure 8.1 shows the territories that each nation settled. Woodard’s argument and the work of cultural geographers suggests that these four nations carried their particular folkways and cultural attitudes with them and that the states they settled still bear those same cultural markings.

The Far West

The cultural migrations were halted for a time by the sheer extremity of the West, which was not well suited to farming. Only two groups braved the arid West. The Mormons hailed from Yankee roots. Like the New England Puritans, two centuries earlier, they set out on a utopian religious mission, and began arriving in the 1840s on the shores the Great Salt Lake in present day Utah. “With a communal mind-set and intense group cohesion,” notes Woodard, “the Mormons were able to build and maintain irrigation projects that enabled small farmers in the region to survive in far Western conditions.” Interestingly, the Mormon values of communitarianism, morality, and good works are all Yankee values. One wonders sometimes why Utah politicians seem to align themselves so often with politicians espousing values more typical of Appalachia and the Deep South rather than with New England.

The other hardy souls to venture into the Far West were the Forty-niners, so named after the year 1849 which brought a flood of frontiersmen to California seeking gold. Otherwise, the West was successfully settled only after the arrival of corporations and the federal government, the only two forces capable of providing an infrastructure that would eventually permit widespread settlement. Westerners would come to resent both the corporations and the federal government as unwelcome intrusions in their lives.

The Left Coast

“Why is it,” asks Woodard, “that the coastal zone of northern California, Oregon and Washington seems to have so much more in common with New England than with the other parts of those states?” The explanation, according to Woodard, is that the first Americans to colonize it were New England Yankees who arrived by ship. New Englanders were well positioned to colonize the area having become familiar with the region as New France’s main competitor in the fur trade.

The first Yankee settlers were merchants, missionaries, and woodsmen. They arrived determined to create a “New England on the Pacific.” The other group to settle the region consisted of farmers, prospectors and fur traders from Greater Appalachia. They arrived overland by wagon, and took control of the countryside, leaving the coastal towns and government to the Yankees. The Yankee desire to reproduce New England was ultimately unsuccessful because as ever more migrants arrived from the Appalachian Midwest and elsewhere, the Yankees were outnumbered fifteen to one. They did manage, however, to maintain control over most civic institutions.

Today the region shares with coastal New England the same Yankee idealism and faith in good government and social reform blended with Appalachian self-sufficient individualism.

Final reflection

While these various European founders of the United States were working out their destinies, the U.S. was also a destination for immigrants from all over the world. Throughout the 19th and much of the 20th century, the majority of immigrants were from Europe, first from northern and western Europe, then from southern and eastern Europe, and then once again from western Europe. From the 1960s on, the majority of immigrants have come from Asia and Latin America.

Given the passage of time and the huge influx of immigrants, it might not seem believable that these founding nations would have maintained their distinct cultural identities. Haven’t they surely been diluted and transformed, asks Woodard, by the tens of millions of immigrants moving into the various regions? It might seem, says Woodard, that by now these original cultures must have “melted into one another, creating a rich, pluralistic stew.”

However, cultural geographers such as Zelinsky (1973) have found reasons to believe that once the settlers of a region leave their cultural mark, newcomers are more likely to assimilate the dominant culture of the region. The newcomers surely bring with them their own cultural legacies, foods, religions, fashions, and ideas, suggests Woodard, but they do not replace the established ethos.

In American Nations, Woodard argues that the divisions in American politics can be understood in large part by understanding the cultural divisions that have been part of the United States since its founding. These divisions can help us understand regional differences in basic sentiments such trust vs. distrust of government. They can also help us understand why certain regions of the country are for or against gun control, environmental regulation, or the regulation of financial institutions, and so on, or for or against particular Congressional legislation.

Application

- Whether you are an American citizen, U.S. resident, or international student … which, if any, of the American national values discussed in the chapter are important where you come from? Which, if any, are unimportant?

- Based on this history of the United States, what adjustments are necessary to the idea of a dominant American culture?

- If you are not an American citizen or U.S. resident, how might the lessons of this chapter apply to your own country?

References

Althen, G. (2003). American ways: A guide for foreigners in the United States. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press.

Bigelow, B. (1980). Roots and regions: A summary definition of the cultural geography of America. Journal of Geography, 79(6), 218-229.

Boorstin, D. J. (1958). The Americans: The colonial experience. New York: Random House.

Fischer, D. H. (1989). Albion’s seed: Four British Folkways in America. New York: Oxford University Press.

Garreau, J. (1981). The nine nations of North America. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Woodard, C. (2011). American nations: A history of the eleven rival regional cultures of North America. New York: Viking.

Zelinsky, W. (1973). The cultural geography of the United States. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Image Attributions

Image 1: “The American Nations Today” by Colin Woodard is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0, used with permission.

Image 2: Table by Nolan Weil is licensed under CC BY 4.0

Image 3: “GezichtOpNieuwAmsterdam” by Johannes Vingboons is licensed under Public Domain

Image 4: “Geographic Origins Map” by JayMan, first published in “Maps of the American Nations” is used under Fair Use. This image is not covered by the CC BY license of this work.

Image 5: Mason-Dixon Line by National Atlas of United States is licensed under Public Domain