4 Material Culture

Nolan Weil

Suggested Focus

This chapter is more impressionistic than the preceding ones. Don’t expect to find answers to the following questions in the text. The best way to get something from the chapter is to read yourself into the text.

- In your own words, explain the point that Henry Glassie is making in the quote that kicks off the chapter. Take it apart and explain phrase by phrase with concrete examples that might illustrate Glassie’s meaning.

- This chapter discusses the differences (rather than the similarities) in material culture from one region to another in the U.S. What are some factors that seem to affect material culture?

- How is material culture a reflection of the life of particular places?

The things we make

“Material culture records human intrusion in the environment,” says Henry Glassie (1999: 1) in his book Material Culture. “It is the way we imagine a distinction between nature and culture, and then rebuild nature to our desire, shaping, reshaping, and arranging things during life. We live in material culture, depend upon it, take it for granted, and realize through it our grandest aspirations.”

In many ways, material culture is the most obvious element of culture. Of particular interest to the cross-cultural explorer is the way that material culture changes as one crosses otherwise invisible cultural boundaries. In traveling from one place to another, it is often the visible change in the manmade environment that first alerts the traveler to the fact that she has crossed from one cultural environment to another. This is not to ignore differences one might notice in spoken (or written) language, or the behavioral routines of people. There may be those too, of course.

Taking to the road

Reflecting on Glassie’s characterization of culture as a record of “human intrusion in the environment,” I am reminded of my encounters with these intrusions in my many travels–east, west, north, and south–across the United States. Traveling by car in 1985 from my hometown of Toledo, Ohio on the west end of Lake Erie through Pennsylvania, upstate New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire to the coast of Maine, I heard English everywhere, of course. But when I arrived in Maine, the accent of the natives was obviously different from my northern Ohio, mid-Western accent. It amused me, for I had previously traveled in the Deep South and was familiar with the many accents of Southerners, but I had never spoken with a native resident of Maine. However, what impressed me more were the differences in cultural landscapes.

In many respects, Maine was strangely familiar to me although the geography is hardly the same as Ohio’s. Let me explain. Northern Ohio is situated in a region of Ohio known as the Lake Plains. Largely flat, much of northern Ohio lies on the southern shores of Lake Erie, claiming about 312 miles (502 km) of Lake Erie’s shoreline. On the other hand, Maine, the northeastern most state of the U.S., is on the Atlantic coast and has a rugged, rocky coastline. Both states have river systems that flow into large bodies of water. The rivers of northern Ohio flow into Lake Erie. The rivers of Maine flow to the Atlantic. Both states have flourishing marine cultures. But it is not the geography I want to focus on.

What struck me just as much as the differences in geography were the differences in the marine cultures of Ohio and Maine. Of course, whether traveling the shoreline of Lake Erie or the Atlantic coast of Maine, one sees many boats. But my impression as a traveler was that the proportion of boats of different types seemed quite different.

On Lake Erie one sees huge lake freighters, especially near big industrial cities like Toledo and Cleveland.

I am old enough to remember when the Edmund Fitzgerald went down in a ferocious storm on Lake Superior on November 9, 1975. It was subsequently immortalized by Canadian folk-rock singer Gordon Lightfoot in a song called The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald.

Commercial fishing boats are also sometimes spotted in the Great Lakes too. Otherwise, the Great Lakes seascape is dominated by recreational craft. Powerboats seem most popular although sailboats can be seen as well. Marinas in Ohio are generally laid out in a series of piers. Since there are no appreciable tides in the Great Lakes, Lake Erie boaters can tie their boats at docks near shore and walk right to them.

The impression is quite different along the Maine coast. Large ships, while sometimes spotted, are more often seen only on the distant horizon. On the other hand, commercial fishing is the lifeblood of coastal Maine, and the lobster boat is an especially common sight. I saw them everywhere.

There are many recreational boats too, and these certainly include powerboats, but somehow powerboats do not dominate my recollections of the Maine coast as they do that of Lake Erie. Instead sailboats seem somewhat more prevalent. And because there are substantial tides along the Atlantic coast, boats are anchored to the sea floor at some distance from shore rather than tied to docks on the edge of the shoreline. A boat owner typically needs to use a small rowboat (or dinghy) to get to the boat (unless she wants to swim). One is also much more likely to encounter a sea kayak in the waters off the Maine coast than in Lake Erie.

Heading Inland

Leaving the shores of Lake Erie and the coast of Maine and traveling inland, both states quickly undergo a cultural metamorphosis. We leave the vehicles and implements of the sea behind and encounter those of the farm and small town. In this sense, whether in Ohio or in Maine, one moves from one cultural setting to another by traveling just a few miles inland. But as we did with coastal Ohio and coastal Maine, let’s compare a couple of material features found in abundance in both rural Ohio and rural Maine.

Whether traveling across Ohio or Maine one cannot go far without seeing a barn. Barns in both Ohio and Maine are generally of two basic types. There are barns with simple gabled roofs and gambrel style barns. Other shapes are sometimes found as well, but the simple gable and the gambrel are typical. Perhaps gambrel barns are more numerous in Ohio than in Maine although I cannot prove it. Barns are often painted red and sometimes white, or maybe not painted at all. But whether red, white, or unpainted, what is notable is that the siding on the barns in Maine is sometimes nailed horizontally, while in Ohio, the boards are often wider, and they are nailed vertically. If there is a reason for these differences other than simple local custom, I do not know. But it does not really matter, for what concerns us here is the raw visual encounter.

Another obvious example of “human intrusion in the environment” is the existence of houses (and other buildings: churches, stores, government buildings, etc.) Houses in both states come in many styles. The ways of building in both states have been influenced by other regions, of course, and by historical developments in architecture. This makes it hard to summarize similarities and differences in the ways of building.

But crossing Maine, the traveler will surely see an abundance of variations on the simple, classic, cuboid designs found throughout New England, including the Cape Cod and the Saltbox.

Moreover, it would not be hard to find houses sided with cedar shakes.

Nevertheless, except for differences in geography, it might be hard for the traveler to tell from a casual observation of houses whether she is in Ohio or in Maine. And frankly, as an Ohioan, I would be hard pressed to name the typical architectural style in Ohio. According to Zillow, an online real estate database company, the most prevalent architectural style in Maine is the Cape Cod design, whereas in Ohio, it is Colonial. In this respect, Ohio resembles Massachusetts or Connecticut more than Maine does. Indeed, architectural preferences in Ohio are somewhat more similar to those of New England generally, than to those of other Midwestern states, such as Minnesota or Nebraska (Home architecture, 2017).

From one end of the country to another

For a more obvious contrast in American architectural styles, the traveler can head south and west from Ohio, down the Mississippi River to New Orleans where the dominant building style is French.

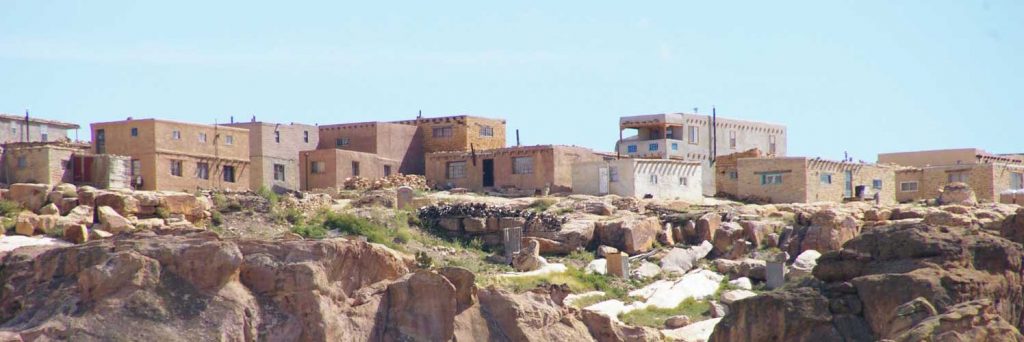

Continuing west into Texas, the traveler begins to encounter Spanish architecture. Further west still, in New Mexico, the cultural landscape features an abundance of buildings in the Native American Pueblo style. Perhaps nothing captures the differences between Texas and New Mexico better than touring the campuses of the University of Texas, in Austin and the University of New Mexico, in Albuquerque.

While the Zimmerman Library at the University of New Mexico was built in 1938, one finds examples of the indigenous architecture that inspired it 60 miles west of Albuquerque atop a 365-foot high mesa in the village of Sky City in Ácoma Pueblo, home to the Ácoma people. According to legend, the Ácoma people have lived there since before the time of Christ. Archaeologists cannot be certain of that but have confirmed that the site has been inhabited since at least 1200 CE, making it perhaps the oldest continuously inhabited community in the United States (Minge, 2002).

Final reflection

So far, we have barely scratched the surface in pointing out some architectural differences across broad regions of the United States. Our purpose, however, is not to make an exhaustive study of American architectural styles. It is only to illustrate Glassie’s characterization of material culture as “human intrusion in the environment” and to call attention to the ways in which that intrusion differs according to local customs, heritage, needs, and tastes.

Buildings are obviously large intrusions in the natural environment, and we have not even begun to look at all the various kinds of structures that comprise the built environment from churches, synagogues, and mosques to government buildings, storefronts, and stadiums. Of course, material culture also includes the associated furnishings, appliances, tools, implements, and personal possessions within buildings.

We are surrounded by material culture. As Boivin (2008: 225) reminds us: “From the moment we are born, we engage in an ongoing and increasingly intensive interaction with environments that are to varying degrees natural and human-made.” They are environments that we have shaped and that in turn have shaped us, “and yet,” notes Boivin, “in many ways, we have barely begun to study its role in our lives.”

References

Boivin, N. (2008). Material cultures, material minds: The impact of things on human thought, society, and evolution. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Zimmerman Library. UNM University Libraries. Retrieved September, 2022 from https://library.unm.edu/about/libraries/zim.php

Glassie, H. (1999). Material culture. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Home architecture style: Regional or not? Zillow. Retrieved August 2, 2017 from https://www.zillow.com/research/home-architecture-style-regional-or-not-4388/

Minge, W. A. (2002). Ácoma: Pueblo in the sky, (Revised edition). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

Image Attributions

Image 1: “Edmund Fitzgerald, 1971” by Greenmars is licensed under CC 3.0

Image 2: “Skyway Marina (Formerly Glass City Marina) – Toledo, Ohio, Ohio DNR” by USFWSmidwest is licensed under CC 2.0

Image 4: “ The Lobster Boat“ by DelberM is licensed under CC0

Image 5: “Northeast Harbor Autumn – Mt. Desert Island, Maine (29773118253).jpg” by Tony Webster licensed by CC 2.0

Image 6: “Sea Kayak” by Thruxton licensed by CC 3.0 “Wood Shingles” by “Malcolm Jacobson” licensed by CC 2.0

Image 7: “Red Barn” by Daniel Case licensed by CC 3.0