7 Group Membership and Identity

Nolan Weil

Suggested Focus

This chapter deals with a complex topic that has generated much scholarly debate. The following questions and tasks will get you started on the road to understanding the issues.

- Give a one-sentence definition of ethnicity. List some features often associated with ethnicity. Identify some other terms that also might suggest ethnicity?

- Why do many scholars now think it is incorrect to define ethnicity in terms of shared culture? How do they now prefer to define it?

- If race is not a biological category, and it is not a cultural category, what is it? How does Appiah prove that racial identification is not necessarily a cultural affair?

- In what way do social classes seem to exhibit cultural differences?

- What is the difference between a country, a nation, and a nation-state? How is a nation like an ethnic group, and how is it different?

- Identify two forms of nationalism. How are they similar and how are they different? What does the work of Theiss-Morse teach us about American national identity?

Preliminary remarks

In this chapter, we will examine the theme of culture as group membership. One of the most common ways that we use the term culture in everyday English is to refer to people who share the same nationality. We think of people from Korea, for instance, as exemplifying “Korean culture,” or people from Saudi Arabia as exemplifying “Saudi culture.”

However, if we are interested in arriving at a coherent understanding of the concept of culture, I believe this usage leads us astray. The idea that culture is a product of human activity and that it includes everything that people make and everything they think and do (together) … that idea of culture seems fairly clear and useful. However, to turn around and call a whole nationality a culture, as we are often tempted to do, is an invitation to confusion.

Perhaps it made sense for anthropologists in the 19th and early 20th centuries who focused on traditional societies to think of the small geographically isolated groups they studied as cultures. Such groups were small enough that for the most part they did share all aspects of culture: language, beliefs, kinship patterns, technologies, etc.

But the large collectives of the modern world that we call nation-states are not culturally homogenous. In other words, we will expect to find different cultures in different places, or even different cultures intermingling with one another in the same places. We say that the society in question is multicultural. What this means for the idea of culture as group membership is that we will need a strategy for identifying the various groups that are presumably the repositories of the many cultures of a multicultural society. One way that sociologists have tried to conceptualize the parts that together make up the whole of a society is by means of the distinction between culture and subculture. On the other hand, historians and political scientists have been more interested in a macroscopic view, inquiring into the origins of nationality and the relationships between such things as nationality and ethnicity.

Cultures and subcultures

According to many sociologists, the dominant culture of a society is the one exemplified by the most powerful group in the society. Taking the United States as an example, Andersen, Taylor and Logio (2015: 36-37) suggest that while it is hard to isolate a dominant culture, there seems to be a “widely acknowledged ‘American’ culture,” epitomized by “middle class values, habits, and economic resources, strongly influenced by . . . television, the fashion industry, and Anglo-European traditions,” and readily thought of as “including diverse elements such as fast food, Christmas shopping, and professional sports.” Philosopher and cultural theorist Kwame Appiah (1994: 116) is more pointed, emphasizing America’s historically Christian beginnings, its Englishness in terms both of language and traditions, and the mark left on it by the dominant classes, including government, business, and cultural elites.

In contrast to the dominant culture of a society, say sociologists, are the various subcultures, conceived as groups that are part of the dominant culture but that differ from it in important ways. Many sociology textbooks are quick to propose race and ethnicity as important bases for the formation of subcultures. Other commonly mentioned bases include geographic region, occupation, social or economic class, and religion (Dowd & Dowd, 2003: 25). Although this way of thinking about the connections between culture and groups has now fallen somewhat out of favor among cultural theorists, it is still common in basic sociology texts. Therefore, we will outline it here along with the caveat that there is an alternative way of looking at group membership, one grounded in the concept of identity rather than of culture.

Ethnicity

The term ethnicity has to do with the study of ethnic groups and ethnic relations. But what is an ethnic group? Let’s start by making clear what it is not. It is not a biological category. Therefore, it is not possible to establish a person’s ethnicity by genetic testing. Instead, an ethnic group is one whose members share a common ancestry, or at least believe that they do, and that also share one or more other features, possibly including language, collective memory, culture, ritual, dress, and religion (Meer, 2014; Zenner, 1996). According to Meer (p. 37), the shared features may be real or imagined. Although sociologists once treated ethnic groups as if they were categories that could be objectively established, at least in principle, many scholars today see ethnicity primarily as a form of self-identification (Banton, 2015; Meer, 2014). In other words, an individual’s ethnicity is not something that can be tested for by checking off a list of defining features that serve to establish that individual’s ethnicity.

If you ask Americans about their ethnic identities, you might get a variety of different answers. Some people will emphasize their American-ness, by which they mean they do not think of themselves as belonging to any particular ethnic group. Others may point to national origins, emphasizing the fact that they are children of immigrants (or even perhaps themselves immigrants). If they identify strongly with their immigrant heritage, they might use a term, such as Italian American, Cuban American, or Mexican American. Americans of African ancestry are likely to identify (or be automatically identified by others) as African American. Americans of various Asian backgrounds, may specify that they are Chinese American, Japanese American, Korean American, etc., — although if they think they are speaking to someone that wouldn’t know the difference, they might just say, Asian American.

A common phenomenon in the United States is the presence of neighborhoods, popularly characterized as ethnic, especially in large cosmopolitan cities. Such neighborhoods result from the fact that the U.S. has historically been a country open to immigration, and immigrants are often likely to settle where their fellow countrymen have previously settled. Many American cities, for instance, have their Little Italy(s), China Towns, Korea Towns, and so on. The residents of these ethnic enclaves might be more or less integrated into the larger society depending upon such factors as how long they have lived in the U.S., or how well they speak English.

A Native American (i.e., an American Indian) might interpret an inquiry about ethnicity as a question about tribal identity. He or she might say—Ute, Shoshoni, Navaho, Lakota, etc. On the other hand, since not all of these tribal names are names that the tribes claim as their own, they may refer to themselves in their native language. For instance, the Navajo call themselves Diné. Tribal affiliations would also be salient in Africa, the Middle East and Central Asia. For instance, two major tribes in Afghanistan are the Tajiks and Pashtuns.

In China, the term minzu (民族) is used to refer to what, in English, we would call ethnic groups. Officially, the Chinese government recognizes 56 minzu. Just how the government decided on 56 as the definitive number of minzu in China, however, is an interesting story. More about that at another time though.

It may be tempting to think that people who share an ethnic identity also share a common culture. Indeed, that is what is implied in calling an ethnic group a subculture. Sometimes it is the case that people who share an ethnic identity are also culturally similar. But it is shared identity and not shared culture that makes a group ethnic. In fact, scholars specializing in ethnic studies have discovered many examples of different groups claiming a common ethnic identity but not sharing a common language, nor even common beliefs, values, customs or traditions. This shows that the connections between culture, group membership, and identity are loose at best.

It is also important to note that ethnic identification is not an irreversible decision. Sometimes people change ethnicity as easily as they might change clothes by simply deciding to no longer identify as, for example, Han 汉族 (the largest minzu in China) but to identify instead as Hui 回族 (one of the largest “national minorities” in China).

Racial identity

Since the demise of the idea that race is grounded in biology—race, like ethnicity, has come to be regarded primarily as a matter of social identity. Also like ethnicity, it is often presumed, incorrectly, that individuals who share a racial identity must share a common culture. As Appiah (1994: 117) has noted, “it is perfectly possible for a black and a white American to grow up together in a shared adoptive family—with the same knowledge and values—and still grow into separate racial identities, in part because their experience outside the family, in public space, is bound to be racially differentiated.” In other words, it is a mistake, not only to assume that race and ethnicity represent biological categories; it is also a mistake to assume them to be cultural categories.

As we mentioned in the previous section, ethnic identification is typically (although not always) self-determined. On the other hand, racial identities are more likely to be imposed on an individual by others. For example, “white” Americans are likely to presume certain individuals to be “black” or African American based on perceived physical characteristics, including skin color, hair texture and various facial features alleged to be characteristically African. Long before “African American” children have ever had time to reflect on matters of identity, that identity has been decided for them. As with any identity, individuals have it within their power to resist ethnic or racial identification. Ironically, the best, and perhaps only way to effectively resist an ascribed identity is to proudly embrace it.

No doubt, one the most well-known Americans to reflect publicly on the perplexities of racial identification in America is Barack Obama, the 44th president of the United States and the first black president. In his memoir, Dreams from My Father, Obama (1995), writes eloquently of the confusion he experienced growing up the son of a white woman born in Kansas and a black man from Kenya. How did Barack Obama come to embrace a black, or African-American identity?

Born in Hawaii, a cauldron of ethnic diversity, peopled by groups from all across Asia and the Pacific Islands, Obama tells a story of race and identity that is nuanced and reflective. Barack’s father was somewhat of a mystery to him since his mother and father divorced and his father returned to Kenya shortly before Barack turned 3 years old. Throughout his childhood, Obama recounts, his white family nurtured in him a sense of respect and pride in his African heritage, anticipating that his appearance would eventually require him to face questions of racial identity. These questions surfaced gradually during adolescence, when he began to experience a tug of war between his white and his black identities.

Inspired by a nationally ranked University of Hawaii basketball team with an all-black starting lineup, Barack joined his high school basketball team. There, he says, he made his closest white friends, and he met Ray (not his real name), a biracial young man who introduced Barack to a number of African Americans from the Mainland. Barack’s experiences in multiracial Hawaii caused him to reflect deeply on the subtle, and sometimes not so subtle, indignities frequently faced by blacks. Increasingly confronted by the perspectives of his black friends and his own experiences with discrimination, Obama writes:

I learned to slip back and forth between my black and white worlds, understanding that each possessed its own language and customs and structures of meaning, convinced that with a little translation on my part the two worlds would cohere. Still, the feeling that something wasn’t quite right stayed with me (p. 82).

Amid growing confusion, Obama writes that he turned for counsel to black writers: James Baldwin, Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes, Richard Wright, W. E. B. DuBois, and Malcolm X. After high school, Barack’s quest continued throughout two years of study at Occidental University in LA before he transferred to Colombia University in New York. Gradually, he constructed a provisional black identity, while never really disavowing his white one.

But it seems to have been in Chicago that Barack Obama finally put the finishing touches on the African American identity that he would eventually embrace when he ran for president in 2008. After years of working as a community organizer in the black neighborhoods of Chicago, he had become well known in the black community. He joined an African American church. And he married Michelle Robinson, herself African American and a lifelong Chicagoan.

President Obama’s story illustrates some of the dynamics involved in racial identification. Obama faced questions of racial identity initially because his appearance prompted people to label him as black. In the end, after years of reflection and self-exploration, including a pilgrimage to Kenya after the death of his father to acquaint himself with his Kenyan heritage, Obama eventually publicly embraced an African American identity.

Social class and culture

Social class refers to the hierarchical ranking of people in society based on presumably identifiable factors. American sociologists, in trying to define these relevant factors more precisely have tended to use the term socioeconomic status (SES) which is measured by combining indices of family wealth and/or income, educational attainment, and occupational prestige (Oakes and Rossi, 2003). While Americans are sometimes reluctant to acknowledge the existence of social class as a determinant of social life in the U.S., scholars have long argued that social class is a culturally marked category. Clearly social class is reflected in the material lives of people. For instance, lower class and upper class people typically live in different neighborhoods, belong to different social clubs, and attend different educational institutions (Domhoff, 1998).

Sociologists argue that different social classes seem to embrace different systems of values and that this is reflected in childrearing. For instance, Kohn (1977) showed that middle-class parents tended to value self-direction while working class parents valued conformity to external authority. Middle class parents aimed to instill in children qualities of intellectual curiosity, dependability, consideration for others, and self-control, whereas working class parents tended to emphasize obedience, neatness, and good manners.

More recent research (e.g., Lareau, 2011) has confirmed Kohn’s findings, further emphasizing the advantages that middle-class parenting tends to confer on middle-class children. For example, in observational studies of families, Lareau found “more talking in middle-class homes than in working class and poor homes, leading to the development,” among middle class children, of “greater verbal agility, larger vocabularies, more comfort with authority figures, and more familiarity with abstract concepts” (p. 5).

According to Kraus, Piff and Keltner (2011), social class is also signaled behaviorally. For instance, in videotaped interactions between people (in the U.S.) from different social classes, lower-class individuals tended to show greater social engagement as evidenced by non-verbal signs such as eye contact, head nods, and laughs compared to higher-class individuals who were less engaged (as evidenced by less responsive head nodding and less eye contact) and who were more likely to disengage by means of actions such as checking their cell phones or doodling (Kraus & Keltner, 2009).

Lower-class and upper class individuals may also embrace different belief systems. For instance, lower-class people are more likely to attribute social circumstances, such as income inequality, to contextual forces (e.g., educational opportunity). On the other hand, upper-class people are more likely to explain inequality in dispositional terms—as a result of differences in talent, for instance (Kluegel & Smith, 1986).

In short, different social classes seem to be distinguished from one another by many of the characteristics that we have previously identified as elements of culture, e.g., patterns of beliefs, values, collective habits, social behavior, material possessions, etc.

Nationality

In this section, we will discuss group membership and identity as historians and political scientists are more likely to view them. Although their interests overlap somewhat with those of sociologists, the main focus of historians and political scientists is somewhat different. Rather than taking the “microscopic” view that seeks to divide a larger culture into constituent subcultures, political scientists tend to take a more “macroscopic” view. Political scientists, in other words, are more interested in exploring how the various subgroups of society relate to the larger political units of the world. Rather than dwelling on subcultural identities, they are more likely to inquire into national identities and the implications this may have for international relations. Let’s shift our focus then from ethnicity to nationality.

Our everyday understanding of nationality is that it refers to the particular country whose passport we carry. But this is a loose way of speaking. According to International Law, nationality refers to membership in a nation or sovereign state (“Nationality,” 2013). Before elaborating further, it will be useful to clarify some terms that are often wrongly taken to be synonymous: country, nation, and state. These are terms that have more precise meanings in the disciplines of history, political science, and international relations than they do in everyday discourse. The non-expert uses terms like country and nation with little reflection, but feels perhaps a bit uncertain about the term state. Let’s define these terms as the political scientist uses them.

First, what is a country? A country is simply a geographic area with relatively well-defined borders. Sometimes these borders are natural, e.g., a river or mountain range. But often they are best thought of more abstractly as lines on a map.

A nation is something entirely different. A nation is not a geographical entity. Instead, it is a group of people with a shared identity. Drawing on the opinions of various scholars, Barrington (1997: 713) has suggested that many definitions seem to converge on the idea that nations are united by shared cultural features, which often include myths, religious beliefs, language, political ideologies, etc.). Unfortunately, this definition of nation has much in common with the definition of an ethnic group. What is the difference? Some scholars believe the difference is only a matter of scale, e.g., that an ethnic group is simply a smaller unit than a nation but not otherwise different in kind. Others insist that because nations imply a relationship to a state, in a way that that of an ethnic group usually does not, it is important to make a clear distinction between ethnic groups and nations (Eriksen, 2002: 97). In other words, as Barrington further emphasizes, in addition to shared cultural features, nations are united in a belief in the right to territorial control over a national homeland.

What then is a state? First, let’s note that by the term state, as we are using it here, we do not mean the subdivisions of a country, as in “Utah is one of the 50 states of the United States.” Instead, we mean the main political unit that provides the means by which authority is exercised over a territory and its people. In other words, the state, as we are defining it here, refers to the instruments of government, including things like a military to counter external threats, a police force to maintain internal order, and various administrative and legal institutions.

Finally, one sometimes encounters the term nation-state. This refers to an ideal wherein a country, nation, and state align perfectly. However, as Walby (2003: 531) has pointed out, perfect examples of the nation-state are rarely found in the real world where “there are far more nations than states.” In fact, nations sometimes spill over the territorial boundaries of multiple states. For example, the Kurds, who can be found in parts of Turkey, Syria, Iraq, Iran, and Armenia, can be seen as a nation without a state. Because they involve territorial claims, efforts on the part of some Kurds to establish an autonomous state are resisted by the governments of Turkey and others, sometimes leading to violent conflict.

Another example of a stateless nation involves the case of the Palestinian people currently living in the state of Israel. Prior to 1948, the land in question had been occupied by Palestinian Arabs. But in 1948, the state of Israel was established, the result of a complicated set of post-World War II arrangements negotiated principally by old European colonial administrators; in the case of Palestine, Great Britain was such an adminstrator. These arrangements made it possible for many Jews returning from war torn Europe to have a Jewish homeland for the first time in 2000 years. At the same time, many Palestinian people found themselves pushed by the newcomers from homes where their families had lived for generations.

Indeed, the conditions under which Israel was established in 1948 sowed the seeds of perpetual conflict, the details of which are too complicated to summarize here. However, the result has been that Israel has become an economically prosperous modern nation-state, and Israelis on the average have thrived. Palestinians, on the other hand, have found themselves dispossessed, oppressed, and robbed of the possibility of national self-determination. For decades, many Palestinians, and indeed most international observers have called for an independent Palestinian state alongside Israel, a “two state solution” to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. Such a solution, however, would require anti-Israel partisans to acknowledge Israel’s right to exist and guarantee her security, and it would require Israel to hand over coveted territories, acknowledge Palestinian grievances, and treat the Palestinian people’s demands for self-determination with respect.

As the above discussion suggests, one reason that issues of national identity are complicated is because the relationships between nationhood, ethnicity, country, territory and state are extraordinarily complex.

The origin of nations

Recall that a nation is a group of people who see themselves as united by various shared cultural features, including myths, religious beliefs, language, political ideologies, etc. Some scholars see nations as having deep roots extending back to ancient times. Smith (1986), for instance, claims that most nations are rooted in ethnic communities and that there is a sense in which nations have existed in various forms throughout recorded history.

On the other hand, Gellner (1983) and Anderson (1991) argue that nations merely imagine themselves as old, when in fact they are really recent historical developments, having only emerged in 19th century Europe with the rise of sophisticated high cultures and literate populations. Gellner and Anderson are counted among a group of scholars often referred to as modernists who argue that while there may have been elites in pre-modern societies with visions of nationhood, national consciousness is a mass phenomenon. According to this view, nations, as we understand them today, only came into being when elites acquired tools for conveying a feeling of national unity to the masses. At first this occurred by means such as print and the spread of universal schooling and later by means of radio, film and television. What Gellner suggests, in fact, is that nations are a product of nationalism, which is not merely “the awakening of nations to self-consciousness,” as nationalists often proclaim, but instead “invents nations where they do not exist” (cited in Erikson, 2002: 96).

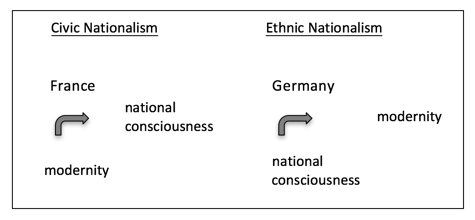

It is perhaps also useful to point out that not all nations came to be nations in the same way, nor are all nations constituted in exactly the same way. Looking at nations in historical perspective, for instance, a distinction is often made between ethnic nations and civic nations. The difference turns on the question of whether the members of a population developed a feeling of national identity before or after the emergence of a modern state. As an illustration, historians often point to Britain and France as the first European nation-states to emerge through a process often described as civic nationalism. In other words, in Britain and France, the rational, civic, and political units of modernity came first, and the development of a national consciousness came later. On the other hand, Germany and Russia followed a path of ethnic nationalism in which the emergence of a national consciousness came first, followed by the development of a fully modern state (Nikolas, 1999).

Where does the United States fit into this scheme? Opinions vary. As Erikson (2002: 138) has pointed out, the U.S. differs in important ways from Europe. For one thing, it has no myths pointing to some supposed ancient origins. In fact, it was founded barely before the beginning of the modern era. This is not to say, however, that the U.S. lacks a national myth; only that it is not a myth lost in the mists of memory.

The American myth is instead a historical narrative stretching back only about 400 years when English settlers began arriving on the continent. The most important chapter perhaps (from the perspective of American national identity) revolves around the difficult and contentious negotiation of a set of founding ideals and principles, articulated in two rather brief documents: The Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Thereafter, the myth continues with an account of the rapid population of the continent by successive waves of immigration from four other continents, Europe, Africa, Asia, and South America. However, in our telling of the national myth, we often omit the shameful history of injustice dealt to the indigenous First Nations (as they are called in Canada), or we treat these details as mere footnotes in a largely Eurocentric, white-supremacist narrative. On the other hand, we usually do confront the history of slavery that nearly tore the nation apart in a civil war. We usually also recount the story of the more than 100-year struggle of African Americans to secure the full rights of citizenship, with its major 20th century victories, as these reinforce a narrative of America striving to live up to its ideals.

Today the United States is often described as multiethnic in the sense that many of its people can trace their ancestry to one or more geographic regions around the world. Indeed, while most Americans speak English, at least 350 different languages are spoken in U.S. homes, including languages from every (inhabited) continent, as well as 150 Native American languages (U. S. Census Bureau, 2015).

But is the U.S. an ethnic nation or a civic nation? Or to put it in historical terms, is the U.S. a product of ethnic nationalism or civic nationalism? Social scientists have often regarded the U.S. as a civic nation but not in the same way as Britain or France. American national identity is presumably based on shared cultural features rather than on shared ethnic heritage. However, American identity is complicated, and current public discourse suggests a sharp divide among American people.

One sees among many American conservatives on the far-right, for instance, a tendency to stress the nation’s Colonial Era origins (1629-1763) with its Protestant (Christian) roots and its Revolutionary Era (1764-1800), featuring the Founding Fathers—who were mostly, white, (male) and English. Theiss-Morse (2009: 15-16) sees this as at the root of an ethnocultural view of American identity. While many Americans may see this as only part of the story, there are some who see it as the most important part. This particular narrative has been the dominant one at various points throughout American history, during which nativist political agendas and restrictive immigration policies held sway. White supremacists often seize upon it in their efforts to marginalize, not only immigrants, but anyone not perceived to be ethnically “white,” Christian, and of European ancestry.

American liberals, on the other hand, are more inclined to emphasize a view, which Theiss-Morse has called “American identity as a set of principles” (p. 18-20). Liberals tend to acknowledge the revolutionary achievements of the Founding Fathers in establishing the noble ideals and liberal political principles of liberty, equality, democracy, and constitutionalism. However, they do not hesitate to recognize that the Founding Fathers were flawed men, some of whom even defended the institution of slavery, while others continued to own slaves even after they saw that it contradicted the founding ideals. Moreover, liberals are more inclined to give equal weight to the story of American immigration, recognizing that the nation’s founding principles made room for newcomers who could come from anywhere and become American simply by embracing those principles. Identity as a set of principles seems more closely aligned to a multicultural, rather than an ethnocultural view of the nation.

While the above contrast somewhat over simplifies American political opinion, it does illustrate the fact that the question of American identity is a highly contested one. Kaufmann (2000) has claimed that the view of the U.S. as a civic nation is supported only if we restrict our attention to developments that have occurred since the 1960’s. According to Kaufmann, for almost its entire history, the political and cultural elite defined the U.S. in ethnic terms as white, Anglo-Saxon, and Protestant. During periods of high immigration, this elite expended great effort to assimilate immigrants to their own ethnic ideal, and when the growth of immigrant populations posed a challenge, defensive responses arose, including restrictions to immigration. In fact, from 1920-1960, this defensive response was institutionalized. After this long period in which national quotas kept a tight lid on immigration, the U.S. only became more open to immigration again in 1965 with the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act.

The tendency, then, to see the U.S. as a civic nation of immigrants is a recent historical development. Nor is the U.S. exceptional in this respect. Rather, the U.S. is merely part of a broader trend among “Western” nations to redefine themselves in civic terms. In fact, Kaufmann (2000: 31) cites research showing that contrary to popular perceptions of the U.S. as a land of immigration, “Western Europe … has had a higher immigrant population than the United States since the 1970’s and by 1990 had proportionately two to three times the number of foreign-born” as the United States.

Whether the post-1960’s immigration trends across much of Western Europe and the United States will continue is currently an open question. A number of events that took place in the second decade of the 21st century seem clearly regressive, including Great Britain’s decision in 2016 to withdraw from the European Union, the rise of far-right challenges to liberal European democracies, not to mention the 2016 U.S. election, which turned the presidency over to an administration apparently committed to recreating immigration policies reminiscent of the exclusionary pre-1965 era.

National identity

Earlier we suggested that anthropologists and sociologists have moved from trying to establish the cultural features that define groups to studying how the members of groups self-identify. Political scientists have made similar moves in their studies of nationalism. Rather than focusing wholly on ethnocultural roots or civic transformations, the recent trend among many scholars is to focus on the social and psychological dynamics of national identity.

Let’s consider the issue of national identity in the United States. Now the criteria of American citizenship are quite clear. Anyone born in the United States or a U.S. territory (e.g., Puerto Rico) is a citizen, regardless of whether one’s parents are citizens or not. Anyone born outside of the United States is a citizen as long as at least one parent is a citizen. And anyone who goes through the naturalization process becomes a U.S. citizen by virtue of established law. Nevertheless, many Americans, despite clearly being citizens (by either birth or naturalization) are sometimes regarded by other Americans as somehow less American. Some Americans, for instance, view themselves as more American if they are white and of English descent, or at least if their non-English ancestors immigrated many generations ago instead of more recently. We refer to this phenomenon as nativism, which is the tendency to believe that the longer one’s ancestors have been here, the greater one’s claim on American identity. And we can call a person who espouses such a belief, a nativist.

To what extent then do individual Americans differ in the degree to which they embrace an American national identity? Elizabeth Theiss-Morse (2009) has studied this question and suggests that Americans can be distinguished from one another according to whether they are strong, medium, or weak identifiers. Furthermore, the strength of national identity appears to be tied to other social characteristics. For example, compared with weak identifiers, strong identifiers are more likely to be: older, Christian, less educated, more trusting of others, and more likely to identify with other social groups in general. On the other hand, black Americans and Americans with extremely liberal political views are less likely to claim a strong American identity.

Strong identifiers are also more likely to describe themselves as “typical Americans” and to set exclusionary group boundaries on the national group—to claim, for instance, that a “true American” is white, or Christian, or native-born. In contrast, weak identifiers are less likely to believe that their fellow Americans must possess any particular qualities to be counted as American.

Final reflection

The relationship between culture and group membership is complicated. Whereas scholars once defined certain types of groups, e.g. ethnic and racial groups, or national groups, on the basis of shared culture, group membership is now more likely to be seen as a matter of social identification. Moreover, social identities are fluid rather than fixed and are established by means of processes whereby group members negotiate the boundaries of the group as well as the degree to which they identify with valued groups.

Application

For Further Thought and Discussion

- Do you belong to a dominant culture in your country, or are you a member of a minority community?

- Do you identify with any particular ethnic group or groups? For each group with which you identify, explain how members of the group define themselves.

- Do you think of yourself in terms of any racial identity? Explain.

- To what extent do you think you exhibit any signs of social class affiliation?

- How would you describe your national identity? How typical are you of other people from your country? … a) very typical, b) somewhat typical, or c) not very typical. … What makes you typical or atypical?

- Some people have more than one identity, or feel they have different identities in different social contexts. We refer to this as hybridity. Do you have a hybrid identity? If so, what is that like?

References

Anderson, B. (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism, 2nd ed. London, Verso.

Anderson, M. L., Taylor, H. F. & Logio, K. A. (2015). Sociology: The essentials, 8th ed. Belmont, Stamford, CT: Cengage.

Appiah, K. A. (1994). Race, culture, identity: Misunderstood connections. Retrieved from https://tannerlectures.utah.edu/_documents/a-to-z/a/Appiah96.pdf

Banton, M. (2015). Superseding race in sociology: The perspective of critical rationalism. In K. Murji & J. Solomos Balwin, (Eds.), Theories of race and ethnicity: Contemporary debates and perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Barrington, L. W. (1997). “Nation” and “nationalism”: The misuse of key concepts in political science. Political Science and Politics, 30(4), 712-716.

Domhoff, G.W. (1998). Who rules America. Mountain View, CA: Mayfield Publishing.

Dowd, J.J. & Dowd, L.A. (2003). The center holds: From subcultures to social worlds. Teaching Sociology, 31,(1), 20-37.

Eriksen, T. H. (2002). Ethnicity and Nationalism: Anthropological Perspectives, (2nd ed.). London: Pluto Press.

Gellner, E. (1983). Nations and nationalism. Oxford: Blackwell.

Kaufmann, E. P. (2000) Ethnic or civic nation: Theorizing the American case. Canadian Review of Studies in Nationalism 27, 133-154.

Kluegel, J.R., & Smith, E.R. (1986). Beliefs about inequality: Americans’ views of what is and what ought to be. Hawthorne, NY: Aldine de Gruyter.

Kohn, M. (1977). Class and conformity: A study in values, (2nd ed.). Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Kraus, M. W., Piff, P. K. & Keltner, D. (2011). Social class as culture: The convergence of resources and rank in the social realm. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 20(4), 246-250. http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/pdf/10.1177/0963721411414654

Kraus, M. W. & Keltner, D. (2009). Signs of socioeconomic status: A thin-slicing approach. Psychological Science, 20(1), 99-106.

Lareau, A. (2011). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Retrieved from http://www.ebrary.com.dist.lib.usu.edu

Meer, N. (2014). Key concepts in race and ethnicity. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Oakes and Rossi, (2003). The measurement of SES in health research: Current practice and steps toward a new approach. Social Science & Medicine, 56(4), 769-784. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00073-4

Obama, B. (1995). Dreams from my father. New York: Three Rivers Press.

“Nationality” (2013). Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved November 23, 2017 from https://www.britannica.com/topics/nationality-international-law

Nikolas, M. M. (1999). False opposites in nationalism: An examination of the dichotomy of civic nationalism and ethnic nationalism in modern Europe. The Nationalism Project, Madison, WI. Retrieved Nov 23, 2017 from https://tamilnation.org/selfdetermination/nation/civic_ethno/Nikolas.pdf

Smith, A. (1986). The ethnic origins of nations. Oxford: Blackwell.

Theiss-Morse, E. (2009). Who counts as an American?: The boundaries of national identity. New York: Cambridge.

U.S. Census Bureau. (2015, Nov 3). Census Bureau reports at least 350 languages spoken in U.S. homes. (Release Number: CB15-185). Retrieved from https://content.govdelivery.com/accounts/USCENSUS/bulletins/122dd88#:~:text=Census%20Bureau%20Reports%20at%20Least%20350%20Languages%20Spoken%20in%20U.S.%20Homes,-Most%20Comprehensive%20Language&text=NOV.,available%20for%20only%2039%20languages

Walby, S. (2003). The myth of the nation-state: Theorizing society and polities in a global era. Sociology, 37(3), 529-546.

Zenner, W. (1996). Ethnicity. In D. Levinson & M. Ember (Eds.), Encyclopedia of cultural anthropology. New York: Holt.

Image Attributions

Image 1: San Francisco Dragon Gate to Chinatown by Alice Wiegand is licensed under CC 4.0

Image 2: Chinese Muslims by Hijau is licensed under Public Domain

Image 3: Obama Family by Annie Leibovitz is licensed under Public Domain

Image 4: Kurdish-Inhabited Area by U.S. Central Intelligence Agency is licensed under Public Domain

Image 5: Israel and Surrounding Area by Chris O is licensed under Public Domain

Image 6: Nationalism Diagram by Nolan Weil is licensed under CC BY 4.0