1 What is a Supply Chain and Why Should You Care?

What is a Supply Chain and Why Should You Care

Ben Neve

Welcome

Greetings, and welcome to a fresh new look at Supply Chain Management!

This text has been designed with both students and professors in mind, focusing on readability, classroom engagement, and real-world connections.

Each chapter includes engaging text, lecture notes, recommended classroom activities, discussion topics, quizzes, and practice exercises. If you have ideas on ways to improve what's being presented here, please reach out to any of the authors so we can incorporate changes into the next version of the text.

Chapter 1 Learning Objectives

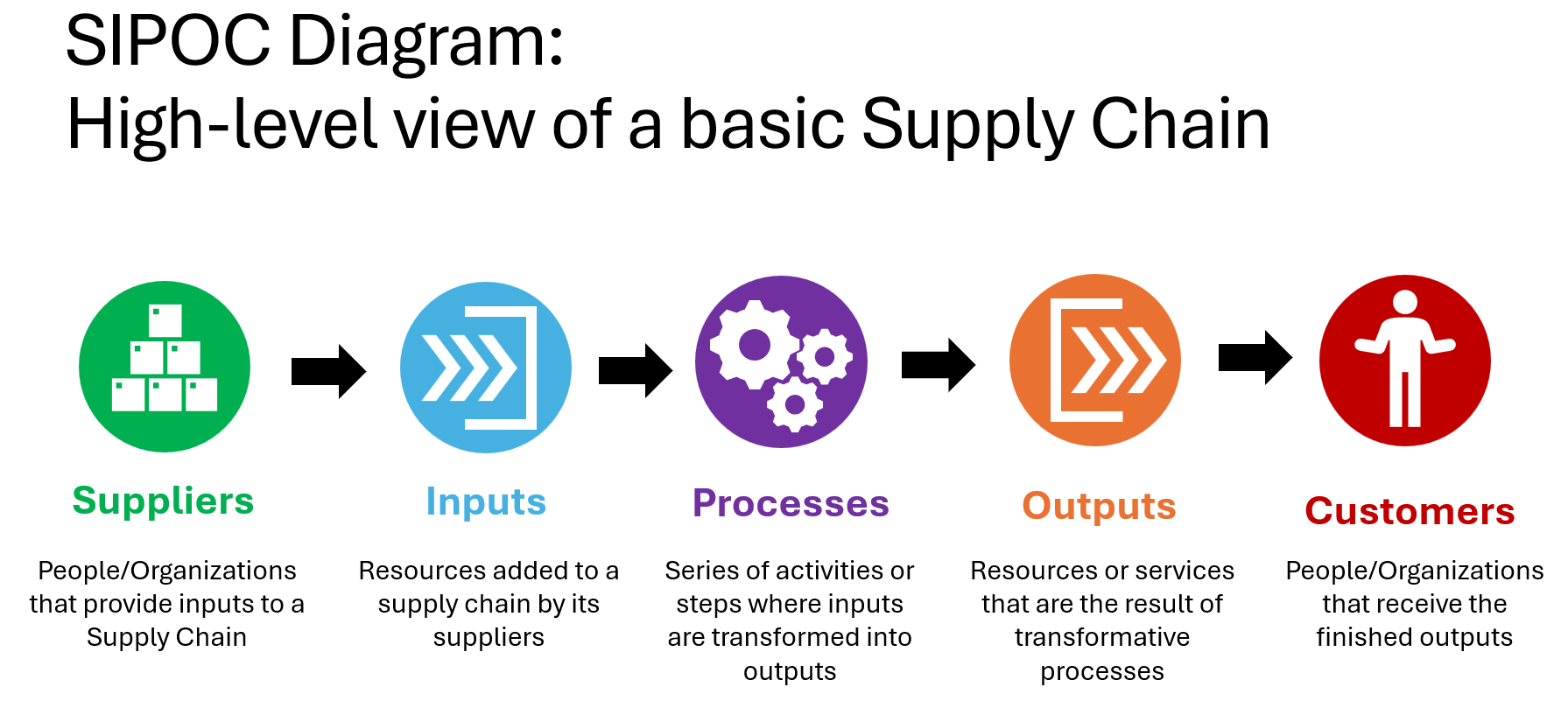

- Describe the components of a supply chain and identify its upstream and downstream components using the SIPOC framework

- Explain the diversity of companies involved in supply chain operations

- Identify and explain how different business functions interact with supply chain management

- Compare and contrast supply chains from different industries

- Explain the global nature and implications of modern supply chains

- Compute dollar productivity, labor productivity, and before/after %-change

To accomplish the above learning objectives, we need to answer two main questions:

- What is a Supply Chain?

- Why should you care?

As we go through the process of answering the first question - what a supply chain is - the second question may seem obvious.

Let's get started!

What is a Supply Chain?

Hint: Supply Chain is a Peanut Butter and Honey Sandwich.

Tribute to the Greatest Sandwich Ever Made

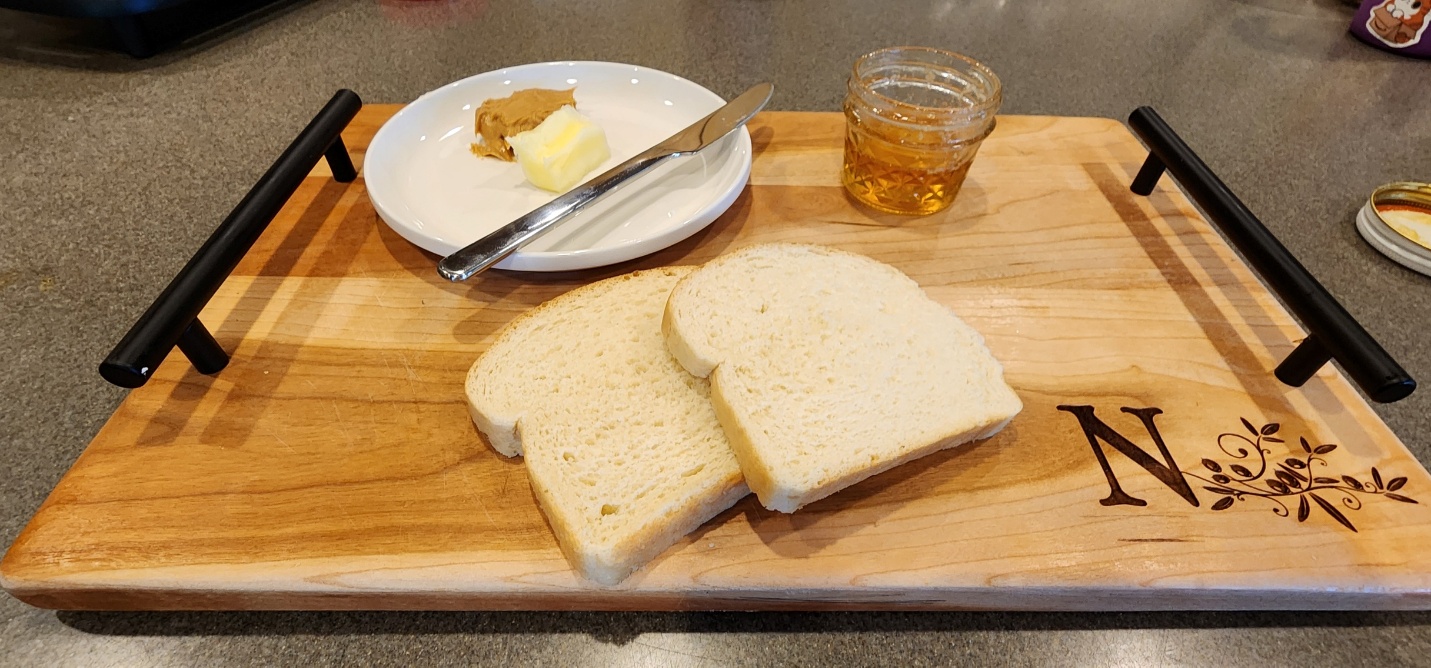

On Thursday, July 17th, 2003 in Cedar City, Utah, a young married couple assembled the best sandwich ever made in human existence. The sandwich? Butter, peanut butter, and honey (PB&H) on white bread – butter being the key ingredient.

There are no pictures of the ultimate sandwich, as it was consumed prior to being photographed. Below you will find a picture of a tribute sandwich, assembled for a photo shoot and promptly eaten before the bread could dry out.

[SIPOC]

The main ingredients SUPPLIER was the Walmart Supercenter five minutes south of the apartment where the sandwich was made. Someone had to drive a vehicle to the store, find and purchase the right ingredients, return to the apartment, and store the ingredients until they were needed.

[SIPOC]

The INPUTS to the sandwich included the ingredients, tools, and labor required to construct it:

- JIF Creamy Peanut Butter (a little more than 1 tablespoon)

- Great Value Sweet Cream Butter (room temperature, a little less than 1 tablespoon)

- Clover Honey (1 tablespoon)

- Grandma Sycamore’s White Bread (2 slices)

- Butter Knife (hand-me-down silverware acquired via Sears Catalogue in the 1980s)

- Zip-Lock Sandwich Bag

- 2-5 minutes of labor per sandwich

[SIPOC]

The PROCESS of making the sandwich is not too difficult:

- Start with two slices of bread, coating one side of each slice with *sufficient* butter

- Spread an inappropriate amount of creamy peanut butter on one buttered slice

- Distribute and spread an ideal glob of honey on the other buttered slice

- Merge the pieces together, literally sandwiching the ingredients between the bread in a manner that wastes none of the honey (think of how many bees contributed to your sandwich!).

- Package the sandwich in a zip-lock bag and prepare for transport to the job site.

[SIPOC]

At the end of the process, an OUTPUT was generated: the sandwich, ready to ship.

We can describe the output in a number of ways:

- the cost of materials and labor (about $0.65)

- the sandwich weight (about 3.5 ounces)

- the sandwich size dimensions (1.25”x 4.5” x 6”)

- the caloric content per sandwich (400 calories)

- the flavor and texture (best sandwich ever made)

- the price paid by the customer ($0.00)

It might be interesting to know that there were two sandwiches made that day, nearly identical, both packaged in individual zip-lock bags and then placed in a brown paper bag. One of the sandwich makers took this bag of PB&H sandwiches to work, with the intent to eat both of them for lunch. The bag sat in the hot car from 7am until 11am, until the road construction crew took a break for lunch.

[SIPOC]

The CUSTOMER was intended to be one of the sandwich makers (from a business standpoint, the sandwich maker could be considered an in internal customer). However, in the middle of July where a residential road was being constructed by a crew of overworked men and women in orange vests and white hard hats, one of the crewmen forgot to bring a lunch. The hungry, handlebar-mustached crewmate of the sandwich maker gratefully accepted one of the car-warmed sandwiches for lunch (the crewmate was an external customer).

How do we know it was the best sandwich ever made? After consuming the sandwich, the crewmate exclaimed “that was the best sandwich ever made!” The following day, the crewmate became the supplier, making his own version of the PB&H as a way to thank the sandwich maker for his kindness in sharing the epic, best-ever-made sandwich in his moment of need.

Unfortunately, it is unclear which half of the young married couple that day actually made the best sandwich ever made, as the sandwiches had been shuffled many times between packing, unpacking, and then sharing with the external customer. Since that time, many sandwiches have been attempted in the same pattern and recipe, and we suspect that many sandwiches have been nearly as good. Since it is very hard to know for sure what the customer experienced for himself, the best sandwich ever made remains elusive.

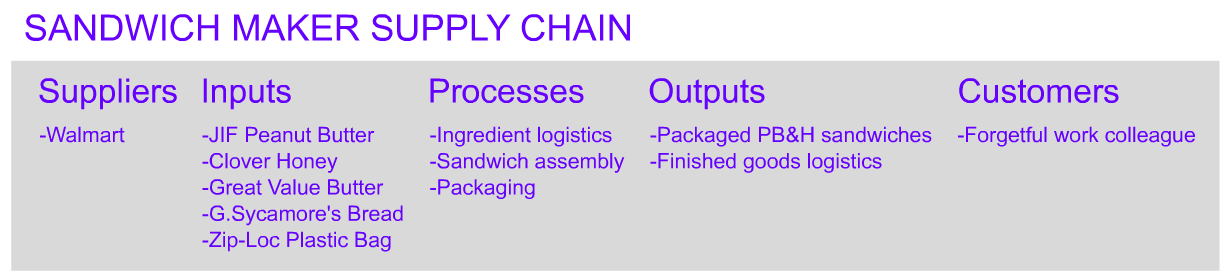

The SIPOC representation of the sandwich maker’s supply chain is shown in the figure. We can see the components listed under each category.

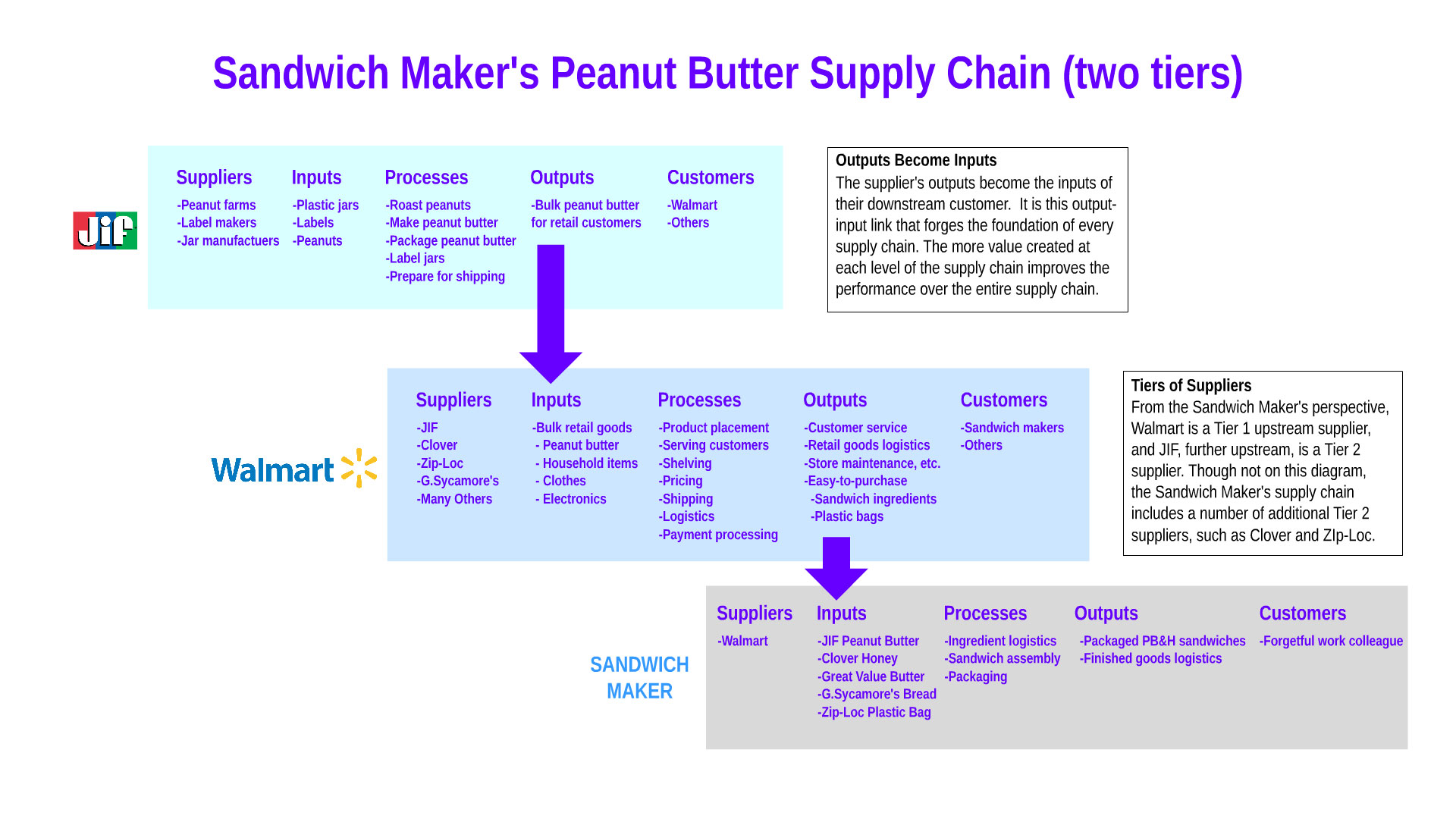

In mapping a larger picture of the supply chain using the SIPOC structure, we can start to see where the SIPOC structures overlap. As you see in the next figure, we are showing SIPOC diagrams for the sandwich maker’s supplier, Walmart, as well as for Walmart’s supplier of peanut butter, Jif.

The diagram shows how the supplier’s outputs become inputs for the next downstream member of the supply chain.

Industrial Supply Chains

If you can recognize the connection of just three entities from the supply chain for a peanut butter and honey sandwich, you will have no trouble seeing the supply chain structure that forms most organizations and businesses.

For nearly every product or service being sold today, there are Suppliers that provide Inputs, Processes that transform those Inputs into valuable Outputs, and, hopefully, Customers that purchase the Outputs.

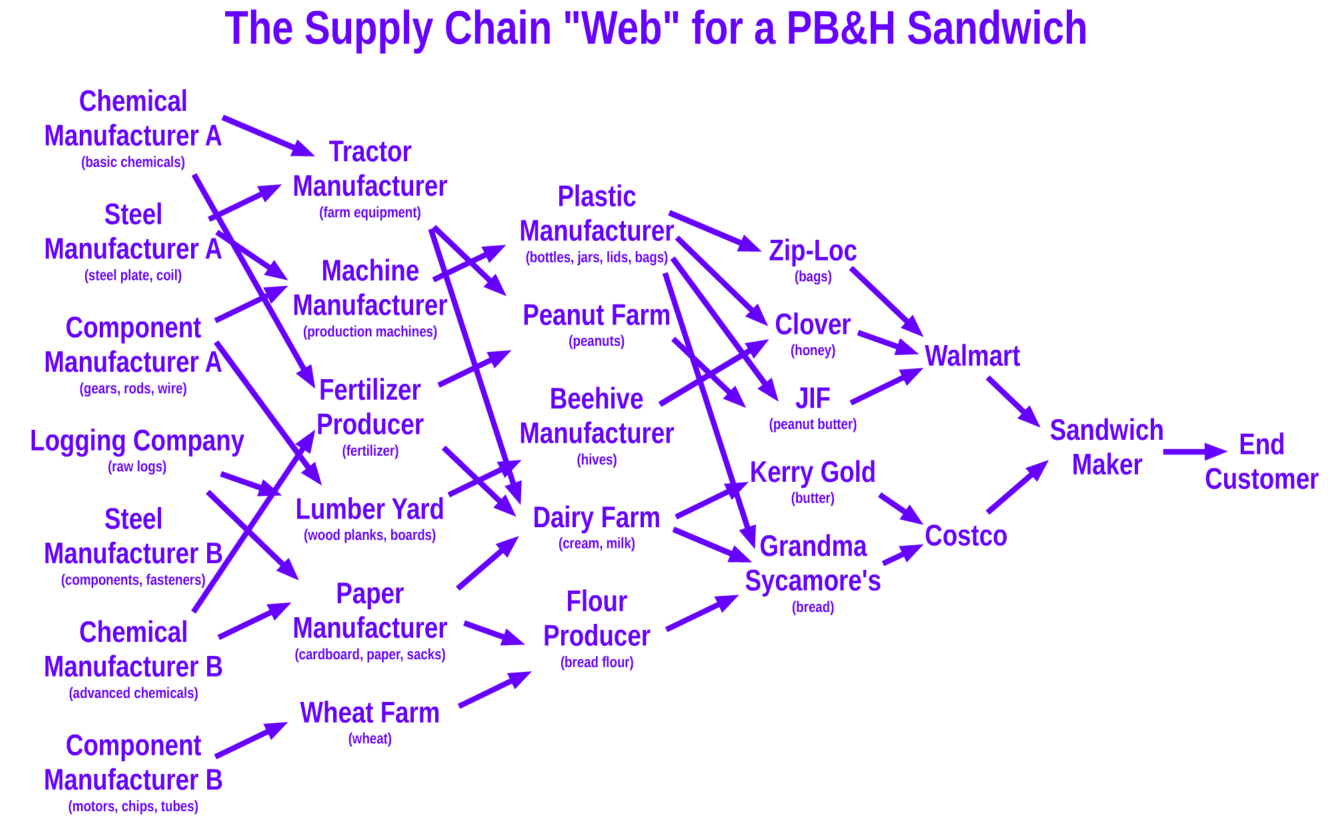

Because of the complexity of today’s global supply chains, the interconnected system of Suppliers, Inputs, Processes, Outputs, and Customers tend to resemble a supply network, or supply web, instead of a simple chain.

Expanding our view of the sandwich supply chain, we can imagine the complexity here is still not even close to representing the full set of interconnected supply chain partners.

Defining SIPOC

Using the SIPOC Model Across ALL Industries and Disciplines

SUPPLIERS

- Accountants use computers, paper, and even information and other digital files to do their work, often supplied by governmental agencies or other third-party software suppliers.

- People working in marketing have to find organizations that can supply them with ad space, whether it's digital or physical, as well as suppliers of printed materials, design work, or even customer data, all to better perform the role of marketing a product or service.

- In finance, data, access to trading platforms, and computer hardware or software are usually supplied by outside organizations. Sometimes financial firms even seek to hire experts as suppliers of unique knowledge or skills to help improve their financial performance.

- In human resources, finding a good supply of talent can be as easy as building a relationship with a college or university career services coordinator, but HR also needs suppliers for skills training, benefits options, and legal counsel.

- Management or business administration majors end up in a wide variety of industries, each of which require suppliers to provide some of the key inputs necessary to perform their work.

- Management information systems (MIS) is an area reliant on suppliers of hardware, software, and even cloud solutions to deliver a functional IT system necessary for all businesses to operate effectively, efficiently, and transparently.

- For professionals in business economics, a big supplier need is in the area of up-to-date information about consumers, businesses, and/or government, often provided by suppliers of data and information through census, survey, or financial data.

INPUTS

As explained in the previous section, every industry uses suppliers of some kind, and those suppliers provide inputs. The inputs can be as real as a vat of molten iron, or they can be digital, like data, software, or other information. In some cases, inputs can even be customers themselves.

In the healthcare industry, which is largely a service industry, inputs include the surgical tools, bedding, medicine, and more, that are used in patient care. However, hospital patients also arrive as 'inputs' to the healthcare supply chain. If patients arrive late, their eventual health and healing can be negatively impacted due to delayed care. Similarly, if a hospital receives a patient for care who has not been following healthy practices, the condition of that patient may be worse, even after the procedures have been completed. It may seem strange that the customer is both one of the inputs, and one of the outputs of the healthcare supply chain.

This is similar to the university "supply chain", where students arrive as 'inputs', and then graduate as 'outputs'. Students may be very familiar with other inputs to university supply chains, namely computers, books, food, paper, printers, facilities, and other campus materials, but do not think of themselves as 'inputs' to the university supply chain.

Other service-oriented supply chains see similar structures, such as auto-repair shops (the customer's car is the input and the output), legal systems (the defendant or plaintiff), hair studio (the customer's hair), and management consulting (the business being consulted is the input and the output), to name a few.

Other inputs include the raw materials, subassemblies, equipment, tools, fuel and maintenance supplies, and other disposable or non-disposable products used for activities throughout the supply chain. It might be interesting to consider the inputs in a job or position related to your major. What are you going to need to have in place to fulfill your work responsibilities (likely supplied by a third party)?

PROCESSES

The process, whatever it is, transforms inputs into outputs. We can also describe the process as utilizing inputs to generate outputs. For a supply chain, the range of inputs is vast, and the amount of processes being performed is equally vast. There are processes for choosing suppliers, designing and acquiring inputs from those suppliers, managing the transportation and conveyance of the inputs to the manufacturing or service locations, the actual manufacturing and/or service processes, the packaging of products and/or completing of services. Then, the outputs - whether a product or a served/transformed customer - must be transported or conveyed to their final destination, where the customer finally pays for the product or service, and then the processes for managing the flow of cash upstream to pay for all the other processes that were performed.

The wide variety of processes being performed in supply chains have generated the nearly countless types of careers and disciplines found in today's global economies. This is why some say that everybody works in "supply chain" - since every business acquires inputs from suppliers, and then performs value-adding processes to transform the inputs into outputs for specific customers. SIPOC exists everywhere, and it hinges on the processes step for any company.

OUTPUTS

This book may talk a lot about the manufacturing side of supply chains, but the content, overall, applies to service-oriented supply chains, too.

Supply chain outputs, then, include both tangible products (smartphones, luxury sports cars, snack foods, etc.) and services (healthcare, automotive maintenance/repair, business services, etc.).

Regardless of whether it is product- or service-focused, the design and nature of the output determines the design and nature of the supply chain's structure. Imagine if a barber decided to start serving hot dogs alongside giving hair cuts. The entire operation would have to change - including the cleanup procedures, the business licensing, the supply base (not many hair supply stores will also sell condiments for hot dogs!), and more.

In a less-extreme case, suppose that Apple decided to change the iPhone so that a battery-charging, hand-operated crank could be attached when away from a traditional source of electricity. This change would require new packaging, new hardware designs, new components to source form new suppliers, and it might reduce the need for a larger battery, so their investments in battery technology might decline. All this to demonstrate that the design of the output determines the design of the supply chain.

CUSTOMERS

To signify the importance of focusing on customers, some disciplines introduce the SIPOC model as the COPIS model (Customers, Outputs, Processes, Inputs, Suppliers). The customer (or our understanding of customers) drives most changes in a supply chain. Customer preferences influence changes in product and service design, which in turn influence the design of the supply chain. Our customers determine whether our product or service is offering enough value to be purchased at the stated price. Though marketing and advertising work to influence the customer perspective, it is still the supply chain, the suppliers, inputs, processes, and outputs, that deliver on that perceived value.

Without customers, there is no business to be had. Customers provide the flow of cash to allow a supply chain to operate, and this flow of cash moves upstream, towards the ultimate suppliers within the supply chain. Looking back at the figure showing the supply web for peanut butter and honey sandwiches, you can imagine the flow of cash going all the way back to the lumberjack who cut down the tree sent to the lumber yard to be cut into boards and sold to the hive builder who made the beehive where honey was harvested, packaged, and shipped to Walmart to be purchased and used in creation of the peanut butter and honey sandwich. Without the customer, the whole supply chain ceases to exist.

Don't forget about your customers!

Productivity Means Business

Now that you understand the SIPOC structure and the complexity of today’s supply chains, let’s introduce the basics of supply chain management. To manage your supply chain well, you need to start by looking to the center of the SIPOC structure: Inputs -> Processes -> Outputs.

Dentist offices transform cavities into healthy, pain-free teeth (a service output) by successfully using dental tools, techniques, and other supplied inputs.

Carmakers transform steel, computer chips, tires, plastic, and other inputs into functional, desirable automobiles (a manufactured output).

Smartphone makers transform their own industry-specific inputs: silicon chips, touch screens, wires, camera lenses, and other electronic components, into desirable outputs. The better they do this, the more customers want to buy their devices. The same goes for carmakers, dentists, and virtually every other organization that provides products or services to either internal or external customers.

If your supply chain can successfully transform inputs into compelling and desirable outputs, your supply chain has created value for its customers. This is why we call supply chain management the value-generating engine of the organization.

A simple way to measure this value-generating engine is by calculating its productivity.

Definition: productivity – the rate at which inputs are converted into outputs, or the rate at which value is generated in a supply chain.

To illustrate, suppose I made you a peanut butter and honey sandwich, but I used poor tools, purchased the most expensive ingredients, made a mess doing it, and I worked for an hour.

EXAMPLE:

Output: 1 sandwich (actually, you’ll want two)

Output: 2 PB&H sandwiches (this is the value being generated)

Inputs:

- Butter @ $1.12 ($0.10 worth of butter on the sandwiches, $1.02 worth of butter smeared on the counter)

- Honey @ $0.55 ($0.30 worth of honey on the sandwiches, $0.25 worth of honey wasted in the sink)

- Peanut Butter @ $0.75 ($0.50 worth of peanut butter on the sandwiches, $0.25 worth of peanut butter disappeared or was consumed by sandwich maker)

- Bread @ $1.50 ($1.00 for four slices of bread, $0.50 for two slices of bread which were dropped on the ground and then thrown away)

- Labor @ $20.00 (for 1 full hour of work, but during that hour I also cleaned up my mess and chatted with the neighbor about using his swimming pool for my birthday party next week).

- Total cost of inputs: $1.12 + $0.55 + $0.75 + $1.50 + $20.00 = $23.92 for two sandwiches

- Total hours of labor: 60 minutes for two sandwiches.

In this example, we’ll compute the total dollar productivity and the total labor productivity:

Total Dollar productivity = (# outputs) / (total $ cost of inputs and labor)

= 2 sandwiches / $23.92

= .084 sandwiches per dollar

This means that if my supply chain makes your sandwiches, it generates less than 1/10th of a sandwich for every dollar that the supply chain uses. Inversely, the dollar productivity shows that the supply chain generates one sandwich for every $11.96 used in the supply chain.

For total labor productivity, we want to measure how well our total hours of labor generated value, ignoring all other factors.

Total Labor productivity = (# outputs) / (total labor hours)

= 2 sandwiches / 60 minutes of labor

= 0.0333 sandwiches per minute of labor

This means my supply chain only generates 0.0333 sandwiches for every minute of labor. We can also look at this as an inverse to see that 1 sandwich required 30 minutes of labor.

A Better Sandwich Making Process

Of course, this represents a terribly unproductive supply chain. In reality, I can make 2 PB&H sandwiches in about 2 minutes with little to no waste, provided I have the right inputs (especially pre-softened butter, a honey squeeze bottle, and a wide-mouth peanut butter jar – all of these are available to purchase if I choose the right suppliers!).

Recalculating my productivity under improved, ideal conditions gives the following figures (assuming no wasted ingredients, and a reduced 2-minute working time):

Total Dollar Productivity= (# outputs) / (total $ cost of inputs)

= 2 sandwiches / ($0.10 + $0.30 + $0.50 + ($20.00 * 2 min / 60 min))

= 2 / $2.57

= 0.78 sandwiches per dollar

Total Labor Productivity= 2 sandwiches / 2 minutes labor

= 1 sandwich per minute

In this case, when my sandwich supply chain is operating with ideal conditions, productivity is massively improved: instead of 0.08 sandwiches per dollar, we are generating 0.78 sandwiches per dollar - almost ten times more sandwiches per dollar used. And instead of one sandwich in 30 minutes, the ideal approach can create 30 sandwiches in the same 30 minutes.

Quick Tip:

You can easily measure the percentage change in any metric by using the formula:

[(New # - Old #) / (Old #)]*100%

Looking at the change in total dollar productivity above, we have:

[(0.78-0.08)/(0.08)]*100% = 875%

The improved method increased total dollar productivity by 875%!

The sandwich example is meant to illustrate how the productivity metric measures a supply chain’s ability to generate value for the customer. We can use the productivity calculation as a baseline, so if we make improvements or the supply chain changes, we can see how things have gotten better or worse.

Improving Productivity: 3 Pillars of Supply Chain

In the previous examples, we used the productivity calculation to roughly measure how efficiently each supply chain generated value for their customers. How could you improve productivity in these examples? Thinking bigger, how could you improve productivity in ANY supply chain?

In most supply chains, we can categorize the efforts into three key areas of supply chain management, where each supply chain management area fulfills specific roles to ensure that maximum value is being generated. The three main areas are: procurement, operations, and logistics.

Procurement

The procurement function requires a wide variety of skill sets, tools, and techniques. Procurement sits right where SIPOC begins, between the Suppliers and the Inputs.

Procurement efforts include finding and researching possible suppliers for every single input used across the entire supply chain. They look across the region, country, and globe to find the inputs that meet their needs, and then they take all the steps necessary to negotiate and agree on prices, set up contracts, build relationships with long-term suppliers, and coordinate with product and service designers to ensure the inputs meet all the specifications needed by the supply chain.

One of my favorite phrases from the procurement side of supply chain is GIGO: Garbage In, Garbage Out. If the procurement function for my sandwiches acquired stale, crystalized honey, margarine instead of butter, and organic/bland peanut butter, then there would be no way to create the best sandwich ever made – the bad ingredients would result in bad sandwiches.

We rely on the procurement function to find and secure the inputs we need to 1) operate competitively in our supply chain now, 2) quickly adjust to changes on the horizon, and 3) continue successfully as an organization for years to come.

Operations

Operations is the very heart of SIPOC: Processes. Operations manages all the transformative steps that convert inputs into outputs. Assembling vehicles. Making food in a restaurant. Minting coins for a nation’s treasury. Supporting the wide variety of patient care efforts in a hospital. Designing and improving rollercoaster waiting lines at a theme park. Manufacturing rollercoasters for a theme park. Producing the machines that help to manufacture rollercoasters. [“Machines making machines?! How perverse!” – C3PO, Attack of the Clones]

Operations manages production, process improvement, quality management, scheduling, job assignments, and everything associated with processes in the SIPOC supply chain structure. Operations management is required for every discipline: economics, accounting, marketing, human resources, management, strategy, etc. The tools and techniques associated with operations management can be applied in each of these disciplines across all industries.

Logistics

Logistics is interwoven throughout the SIPOC structure and is concerned with ensuring that everything is in the right place at the right time. One procurement has finalized a supplier for a product, the logistics function makes sure it gets picked up, shipped, stored, organized, protected, and then positioned in the best place for the operation function to do its job.

Within the operations function, logistics is there, supporting the movement and positioning throughout the journey from input to output.

When the finished product or services are ready to be delivered, logistics ensures delivery occurs on schedule, to the right place, with everything in the same condition as when it left the operations function.

Logistics is a lot more than truck drivers, warehouse workers, and fork lift operators. The logistics function helps to design the best way to utilize all of these elements, and more, to save money, improve service, and manage the team to perform consistently day in and day out. Logistics also concerns itself with analysis of the flows and disruptions throughout the entire supply chain. Logisticians may find themselves working with real-time tracking software that monitors movements of incoming and outgoing supplies across the entire planet. They help to plan, coordinate, and direct this complex function.

Why should you care?

We now know what a supply chain is, and we even know how to measure basic productivity.

We know that for Supply Chains to be effective, Procurement, Operations, and Logistics must work together daily.

Procurement works with Logistics to make sure the supplies are delivered to Operations, where Operations strives to generate maximum value. Once Operations is done with the transformation processes, they work with logistics to make sure all the appropriate outputs end up in the right place at the right time. They connect and enable every part of SIPOC.

But why should you care?

Because every organization operates as, or is part of, the SIPOC structure of a supply chain. And beyond the three supply chain pillars, the ENTIRE organization is also part of the supply chain team.

- Economists study the global and regional trends in supply and demand, critical to designing supply chain networks and positioning resources.

- Marketing interacts with customers who want the products and services generated by the supply chain.

- Accounting and finance ensure that financial flows are successfully meeting the organization’s needs throughout the supply chain processes, from procurement to logistics to operations to delivery.

- Human resources helps to find key talent or training solutions to fill skill gaps throughout the supply chain.

- Management Information Systems builds and maintains the software and hardware backbone that carries information and data to all team members and enables technological advancement.

- Engineers and designers create products and services to meet the needs of customers.

- Subject matter experts, skilled service employees, and frontline laborers work to transform inputs into outputs.

All of this is happening in concert with the three supply chain pillars, working to create and deliver value to the marketplace.

Working within a successful supply chain provides opportunities for analysis, teamwork, relationship building, problem solving, leadership, and rewarding personal growth as you make significant impacts on the organization.

We all care about supply chain, because we are ALL part of one.

"You best start believing in ghost stories, Miss Turner, you're in one!" - Captain Barbossa, Pirates of the Carribean, Disney (C)

WHAT COMES NEXT

Looking ahead to the rest of this textbook, we will explore the field of supply chain management at an introductory level. We will go through the key tasks of supply chain managers in the next chapter, followed by how to work well with people, both in teams and in other supply chain partnerships.

You’ll learn how to work with data at a basic level, and then use your new data skills to try your hand at supply chain analysis, both to predict the future and to manage your product on the shelf so that you can satisfy all of your customers.

Beyond this, you’ll be exploring sustainability, quality and problem solving, the tools of logistics, and risk management.

It is a great set of skills applicable to every major, giving you the leader’s view of a business, from suppliers to customers and everything in between.

Discussion Questions

- What is the best sandwich you've ever eaten? With a team of three people, how many sandwiches of that type could you make in one hour?

- After participating in the classroom activity, discuss with a 'competitor team' about how your different SIPOC models compare. What did you learn?

- Who are the 'customers' of a University or College? What are the 'outputs' of a University or College? Who pays? Who benefits?

Essay/Reflection Questions:

- Mapping SIPOC for your own major: Based on a potential career in your field, what might the SIPOC model look like for your future company/position/role?

- Consider the three main pillars of Supply Chain Management: Operations, Procurement, Logistics. What job/technical skills or characteristics do you think are unique to each area? Which skills/characteristics are similar across the three areas?

- How might generative AI affect productivity of a supply chain? How do you think organizations should adjust or modify their workforce or the compensation of their workers as a result of productivity gains?

Calculation Exercises:

Problem 1 – Smartphone manufacturing productivity

Wolfconn smartphone assembly pays employees $15 per hour to assemble devices. The cost of raw materials is $55 per smartphone. At the end of a four-hour shift, 10 employees were able to assemble 84 phones - which is a pretty typical day at Wolfconn.

- What was the total dollar productivity for Wolfconn?

- What was the total labor productivity?

After finding a new supplier for smartphone chips, the raw material costs went down to $42 per phone. Additionally, a new work incentive allows a work shift to end after the team of workers assembled 80 phones. The most recent production numbers were that 10 assemblers were able to assemble 80 phones in three-and-a-half hours.

- What is the new total dollar productivity?

- What is the new total labor productivity?

- How has Wolfconn's productivity changed with the new conditions?

Problem 2 – Veterinarian productivity

7 Valleys Veterinary Clinic puts on a "get your shots" campaign every Spring and Fall near the Piggly Wiggly in Jackson, Mississippi.

Last Spring, four Veterinary techs and a Veterinarian were able to give rabies shots to 58 pets in a three-hour period. The Vet techs were paid $20 per hour, and the Veterinarian was paid $100 per hour. The clinic paid a combined $174 for the syringes, shot solution, and gloves.

- What was the total dollar productivity for 7 Valleys Vet Clinic?

- What was the total labor productivity?

- (BONUS) If the clinic wants to make a profit of $5 per dog, what should they charge pet owners to bring a pet to the "get your shots" clinics?

This Fall, the clinic went a bit differently. One of their Vet techs called out sick and the Veterinarian only worked for half of the three-hour clinic event. 45 pets received shots, and the materials cost $140 overall.

- How did productivity change?

Problem 3 - Chair make productivity

Charlie's Chairs builds handmade chairs in Oakville, Pennsylvania, with a team of 6 employees. Two Varnishers work for 8 hours per day at $20 per hour, applying varnish, sanding, and finishing the chair coating. The four chair builders, paid $25 per hour, work similar 8-hour shifts, but they start earlier in the day. The builders operate lathes, sanders, saws, and other tools to build chairs from raw oakwood.

The total cost for chair materials, including wood, screws, sandpaper, glue, and varnish, costs about $50 per chair.

For an average day (8-hour shift for everyone), Charlie's Chairs produces 30 chairs from start to finish.

- What is the total dollar productivity?

- What is the total labor productivity?

- If Charlie's Chairs wanted to break even financially, how much should customers pay for each chair?

Samantha Bench, one of the Varnishers, figured out how to use a heat gun to speed up the chair-drying process. Using the new technique, the varnishers can reduce the varnishing time by two hours and cut back on the amount of varnish they use, saving $2 per chair in materials. George Hinder, a chair builder, created a jig for chair assembly that reduces build time. Overall, they can now produce 32 chairs, using only 6 hours of varnisher time (2 varnishers for 6 hours) and 7 hours of chair builder time (four builders for 7 hours).

- How did productivity change?

- How should these workers be rewarded for their efforts to improve productivity at Charlie's Chairs? [Bonus]

Appendix 1: SIPOC Classroom Activity

(Approx. 30-45 minutes)

As an activity on the first day of class, we recommend breaking class into teams of 3 to 5 students, and letting them choose one of the products or services below, or use some of your own examples (no two teams should have the same selection):

- Red Baron Pepperoni Pizza

- Pepperoni Pizza from a local pizza restaurant (we use The Pie Pizzeria near campus)

- Jeep Wrangler Unlimited Rubicon

- Rivian R1S

- Apple iPhone 16 pro

- Google Pixel 9

- Dental services from a local dentist office

- Veterinary services from a local veterinary pet care office

- A favorite pair of shoes from an online store

- A favorite pair of shoes from a brick-and-mortar store

Once the teams are selected and the product/service is chosen, set students up near a wall with either a white board or an oversized hanging note pad so they can record their work.

Walk the students through the some of following prompts, working upstream through the SIPOC structure, starting with the Customer.

Customer

Who is the ideal customer for this product/service and Why? (Any among the group?)

What does the customer expect vs. what does the customer get? (Any gaps?)

Where are the customers located (generally) when they buy the product/service? Where do they use the product?

When do customers buy or use the product/service? (time of life, time of year, time of the day, etc.)

How long are customers willing to wait for the product/service after they pay for it?

Output

How much does the product/service cost to the customer? (Is it worth it?)

Where is the product made vs. where are the local customers located? (places, distances?)

How does the product/service get to the customer?

What/Who are the market competitors of this product/service? (Any that your team likes better? Why?)

Process

How many steps does it take to create the product/service? (How much time does it take?)

Where does the process of production/service occur? (How far from the customers?)

What skills/training are required to create the product/service?

How much does it cost to produce/serve to the company performing the process? (i.e. the manufacturer or service provider)

Inputs

What raw materials are required to create the product/service? (Tools? Machines? Utilities?)

How many different types of raw materials are needed for production/service?

How do the materials arrive? (packaged, unprocessed vs ultra-processed, ready to assemble, etc.)

How long does it take to get the materials if they run out?

Suppliers

Where do the inputs come from?

How far are the suppliers from the production/service process?

How far are the suppliers from the customers?

How do the suppliers create the raw materials?

Who supplies the suppliers?

ACTIVITY OBJECTIVES:

- Break the ice (allow students a first chance to get to know their peers and their instructor in an engaging setting)

- Reinforce the basic components of the supply chain’s SIPOC structure

- Introduce thinking about how supply chains operate (movement of goods, global reach, variety of industries, etc.)

Media Attributions

- Map Screenshot © Ben Neve is licensed under a Public Domain license

- SIPOC Diagram © Ben Neve is licensed under a CC BY (Attribution) license