2 Creating Value for Customers

From Planning to Delivery

Francois Carrier

Learning Objectives

- Define the concept of customer value and identify its core components

- Define the key supply chain processes of Plan, Source, Make, Deliver, Return, and Enable, and explain their purposes within a supply chain

- Illustrate how each process contributes to the end-to-end flow of goods and services in a supply chain using real-world examples

- Analyze a simple supply chain scenario to identify where customer value is added or lost across the key supply chain processes

- Identify different career paths in supply chain management

John Hanson sat at his desk, deep in thought and troubled by what he had just read in the morning’s logistics report from the Wall Street Journal. A large container ship bound for Marseille, France, had run aground in the Suez Canal, blocking all traffic in both directions. The article gave no indication of the time it would take to restore traffic through the Red Sea. It only said that rescue operations were underway, but were progressing slowly. The sight of dozens of ships adding up every day to the line of vessels waiting for passage formed in John’s mind. A buyer for Advanced Aerospace Supplies (AAS) in Ogden, Utah (USA), John was worried about the impact of the incident on his company.

AAS is a large distributor of precision aircraft parts serving the rapidly growing defense and aerospace industry in Northern Utah. Avionique de France (AdF), AAS’s sole supplier of electronic engine controls (EEC), is located in the heart of the French industrial, aerospace complex in Toulouse. EECs are the core of the engine management system, receiving data from numerous sensors, and adjusting fuel flow, airflow, and ignition to ensure efficient and safe engine operation. John knew that many of the semiconductors in EECs were manufactured in Taiwan, and travelled through the Suez Canal to reach the French plant. There were perhaps many more raw materials and components of the EECs, such as plastic pellets, metal alloys and even rare earth minerals, John did not know about, that were stuck in transit.

As fate would have it, AAS had received the day before a large order for EECs from the Delta Airlines maintenance hub in Salt Lake City, more than he could supply based on existing inventory. John needed to place a new order. He needed 10 units as soon as possible to satisfy the Delta order, plus a few more to replenish his stock. That’s more than AAS typically sold in a quarter! John was about to find out how easy it was going be to get more EECs.

It was 5 pm in France. There was not a minute to waste. John picked up the phone immediately to call François Martin, his contact at AdF. He was eager to learn about his supplier’s ability to deliver a large order of EECs.

Calling the French supplier was always an adventure. John had been on business trips to France many times. Although he could not speak the language, he understood the culture well. He thoroughly enjoyed the delicious food, refined architecture and Mediterranean climate of Southern France, but could never quite get used to the poor customer service he experienced in many parts of the country. He knew he would first have to get past a barrage of receptionists, most of whom only spoke basic English. Then, after repeating himself three times, perhaps he might be able to talk to François. That’s when the real fun would start.

After giving John an earful about the never ending perils of American politics, François would complain about practically everything. The incident at the Suez Canal would no doubt trigger a lengthy monolog. All of it in a thick French accent. When it came to discussing business, François was not only direct, but also tough as nails. Even though he and John had worked together for many years, François would rarely make a price concession, go out of his way to speed up a delivery, or agree to a last minute change to the product configuration. Citing manufacturing constraints, company policies or another excuse, François would usually respond to John’s requests with a no.

As he was dialing François’ number, John thought about what awaited him. Why would anyone work with such a difficult supplier? He surprised himself thinking: “they have the best product in the market: highest safety ratings, and most innovative technology; the after-sale service sucks but their parts never fail.” And it was always fun to reconnect with François that he knew he could trust, and for whom he had great respect. When John was not negotiating a difficult deal with François, he might even call him a friend.

Defining Customer Value

John and François are on opposite sides of a buyer-supplier relationship. The fact that the relationship has been going on for a long time suggests that it is mutually beneficial. We might even say that John and François need each other. John needs technical avionic products that are highly reliable; and François needs customers willing to pay the prices being charged. Their relationship revolves around a winning customer value proposition.

The customer value proposition concisely states what makes the company’s products valuable to buyers, and communicates to current and future customers the unique benefits they can expect to receive from the company’s products and why they should choose that company over another[1]. For example, Apple’s value proposition is to provide innovative, high-quality products with a focus on user experience and integration into a seamless ecosystem of hardware and software. Another example is Walmart, whose value proposition is captured in the slogan “Everyday Low Prices.” Amazon, a competitor of Walmart, seeks to differentiate itself from Walmart by providing customers with convenience, affordable prices and a vast selection of products.

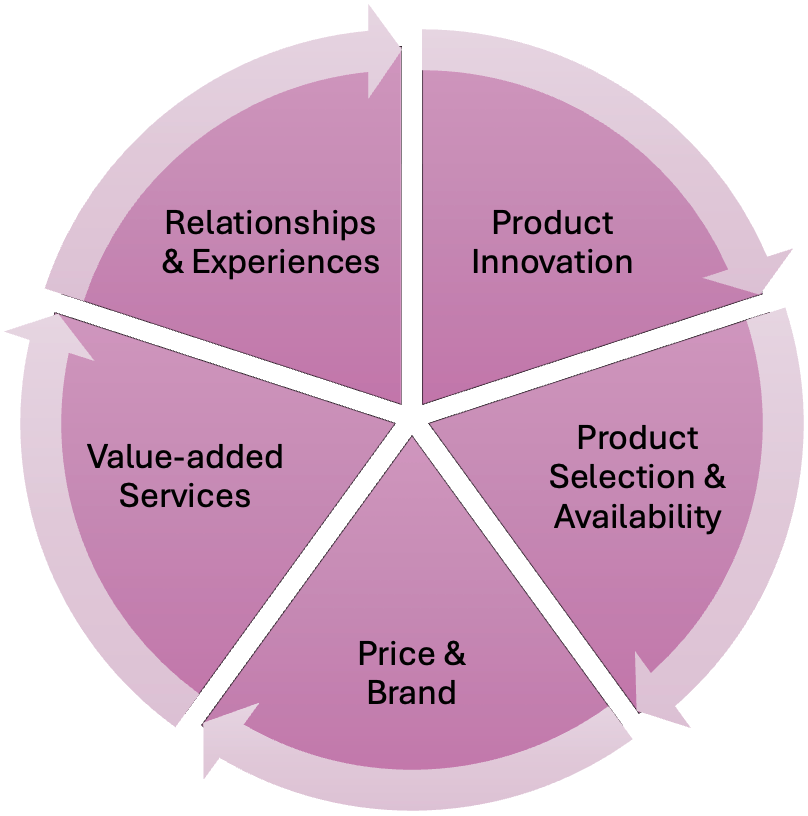

Customers perceive and experience value in different ways. That’s why companies in the same industry can differentiate themselves from each other by prioritizing different dimensions of customer value. When thinking about a company’s value proposition, it is helpful to consider the following five dimensions proposed by Dr. David Simchi-Levi at MIT[2] (See Figure 2.1):

- Product innovation: Product innovation denotes the introduction of new products or new product features in the market. Product innovations add value to customers through improved product performance, reliability, durability, serviceability or aesthetics. In our opening story, John kept returning to AdF because they had the most innovative product in the industry with excellent reliability and an unmatched safety record. Product innovation was important for John, and he perceived AdF to be a highly innovative company.

- Product selection and availability: In the age of Amazon and Alibaba, customers have become used to finding anything they want online. Thus, product selection and availability is an important dimension of customer value. Note that choice and availability refer to two different but related concepts. A proliferation of products gives customers plenty of choice, and can help the company capture a larger size of the market. However, the company may not be able to hold inventory for all possible product configurations. In particular, low-selling products may not be immediately available. Conversely, a company could limit the number of products in its portfolio, and carry inventory of each product variant to maximize availability. This is the strategy adopted by Apple for the iPhone. Note that product availability also refers to the company’s delivery performance in terms of speed or reliability. In the above case, John is happy to buy the standard EEC model from AdF. Since EECs are expensive to manufacture, he doesn’t think AdF has many of them in stock. Therefore, he is worried about product availability, and the time it will take AdF to fulfill his large order, especially in light of the blockage affecting the Suez Canal.

- Price and brand: Price is an essential dimension of customer value. Many factors contribute to price including supply and demand considerations. Demand is directly influenced by customer willingness to pay, which is the maximum amount of money a customer is willing to spend on a product or service. The higher the customer willingness to pay, the more the supplier can charge. Customers generally prefer lower prices. However, a strong brand reputation signals quality and prestige, which is attractive to customers, and increases their willingness to pay. This is why positive brand effects usually result in high prices. Back to our opening story, John’s willingness to pay for EECs is on the rise because he worries about a potential supply shortage, has no other viable options, and does not want to disappoint his client. In this context, François has little reason to make price concessions even for a large order.

- Value-added services: In highly competitive markets, companies cannot compete on price alone. To avoid cut-throat competition and the resulting razor-thin margins, they need to distinguish themselves from competitors. One way to do so is to offer value-added services that support, complement, and expand their core product offerings. These include after-sale services, warranties, real-time information services or other digital offerings. This is an area in which AdF excels since its EECs are equipped with real-time monitoring and AI-enabled predictive models that can alert the aircraft operator about potential breakdowns before they occur; all of this for a monthly subscription fee.

- Relationships and experiences: A relationship adds value to buyers and sellers through shared experiences that promote trust and goal congruence over time, and enable them to collaborate and meet customer needs more efficiently and effectively. In John and François’ business-to-business (B2B) context, such a long-term relationship can be called a strategic partnership. In the business-to-consumer (B2C) world in which we all live, companies understand that providing exceptional customer experiences builds brand loyalty, which can improve the company’s long term prospects. An exceptional customer experience “encompasses every aspect of a company’s offering—the quality of customer care, of course, but also advertising, packaging, product and service features, ease of use, and reliability.”[3] Relationships and experiences are perhaps what explains the deep sense of mutual trust and connectedness between John and François.

Note that, while the above dimensions cover the core components of a customer value proposition, they may contradict with each other, forcing managers to navigate complex trade-offs. For example:

- A new product (product innovation) may not be available in large quantities, or offered with many options (product selection & availability);

- A value proposition focused on low prices (price & brand) may deliberately limit the breadth of the product portfolio (product selection & availability) to save on inventory costs;

- In a low price strategy (price & brand), profit margins are usually thin. This can limit the company’s ability to invest in building relationships and providing unique customer experiences (relationships & experiences).

As much as a company might want to excel in all five dimensions, this is usually not possible for financial, technical or other reasons. In general, managers need to choose among competing priorities. In other words, they need to be strategic.

Supply Chain Strategy

As A.G. Lafley, former CEO of Proctor & Gamble, once said: “Strategy Is choice.”[4] Strategy involves making a series of deliberate choices aimed at achieving success. It is a coherent and tailored approach that sets the company apart within its industry, enabling it to build lasting competitive advantages and deliver greater value than its competitors.

Choosing which dimensions of customer value to emphasize is a strategic choice that will impact customer perceptions, and which markets the company can successfully serve. The choice will also dictate how the operations and supply chain functions should be organized to deliver the promised value.

Aligning the supply chain strategy to the business customer value proposition is critical to the company’s success. The three dimensions of product innovation, product selection & availability, and price & brand are especially important for designing a supply chain strategy, as the following examples illustrate:

Product Characteristics: Functional versus Innovative

When it comes to innovativeness, products fall on a spectrum: at the low end, functional products, including commodities such a gasoline, milk and diapers, have a long product lifecycle. This means that their design does not change much over time, and new product variants are rare. At the high end, innovative products such as cars and cellphones have a short lifecycle, with new designs released frequently.

Gasoline, for example, is a functional product. Customers are fine with a limited selection of fuels at their local gas station, but they expect very high availability. An equally important consideration driving their gasoline purchases is price. Moreover, the demand for gasoline is predictable: people commute to work or school during the week, and drive longer distances on weekends and during the summer. The same is true of all functional products: demand is easy to predict and prices and profit margins are low. Therefore, the appropriate operations strategy for a functional product should emphasize cost reductions by exploiting economies of scale in production and transportation (for example by only using full truck loads) to deliver products just in time, and removing redundancies and waste. Such an approach is called an efficient supply chain strategy.

Conversely, innovative products require a different operations strategy because, for one, customer demand is much more difficult to predict: no one knows for sure if the new product will be a commercial success, and if it is, which specific product configurations will be most popular. Fortunately, the profit margins are high because new products generally command premium prices. This means that the company has the resources needed to invest in excess production or transportation capacity, carry more inventory, or pay for speedy deliveries to respond to unpredictable changes in demand. In other words, the company can invest in a responsive supply chain strategy.

Clearly, different product characteristics call for distinct supply chain strategies. Likewise, different channels for reaching customers usually require distinct strategies.

Channel Characteristics: Brick-and-Mortar versus Online

Since the beginnings of the Internet, online retail sales have grown steadily, and continue to expand. In 2025, e-commerce retail sales represented 16% of all retail sales in the U.S.[5]

If you’ve ordered anything online, you know how convenient it is. The prices are comparable to what you might find at the local store, and the added shipping cost (if not waived) is a small price to pay for the convenience of placing an order from your couch (especially during a snow storm). Perhaps more importantly, online retailers offer a selection of products that is difficult to match. Even a Walmart Supercenter with its 120,000 products in stock looks tiny compared to the 600 million products sold on Amazon. If you’re looking for something unique, you may not find it at your local supermarket, but there is a good chance it is available online.

Although brick-and-mortar retailers offer less choice, they have other advantages: you can visit their stores, see the product for yourself, try it on or get some advice from a salesperson, and if you like what you found, drive home with the product. However, if you order online, you will have to wait for the item to be delivered to your home. Thus, another point of difference between brick-and-mortar stores and online stores revolves around the ‘last mile,’ which is the last leg of the supply chain journey between your home and the retailer’s closest location. To compete with brick-and-mortar stores, online retailers have to speed up the time it takes to fulfill a customer order. This is called the lead time. Speeding up last mile deliveries is particularly challenging. In general, home deliveries are very expensive, and most online retailers lose money on them. Even Amazon with its massive scale and enormous investments in last mile delivery has yet to find a way to deliver products to customers’ doorsteps profitably.

The rise of online shopping has also brought about the explosion of returns, which also calls for dedicated supply chains. In summary, brick-and-mortar and online distribution channels require markedly different supply chain strategies. The main differences are outlined in Table 2.1.

| Brick-and-mortar | Online | |

|---|---|---|

| Customer interaction | In-store checkout, Returns at store | Online checkout platform, Returns shipped back or dropped off at a return location |

| Inventory location | Held at physical store | Centralized in fulfillment centers or, for bulky items, sent directly to customers from manufacturers (i.e., drop-shipped) |

| Distribution network | Goods shipped in bulk to store from regional distribution center (DC) or manufacturer | Goods shipped individually to customers from fulfillment center |

| Technology infrastructure | Point-of-sale (POS) and in-store inventory systems | E-commerce platform, online order management and logistics software |

| Logistics complexity | Simpler last-mile, but complex inventory spread across stores | Complex last-mile delivery, especially for high sales volume or large geography |

The Niche Strategy

Avionique de France, in the opening story, has found a niche in manufacturing highly specialized aviation products with advanced technical features that are not easily replicated by competitors. In such a narrow and well-defined market segment, product innovation and relationships are paramount. The corresponding supply chain strategy relies heavily on producing small quantities of customized products using on-demand manufacturing, meaning that products are made to order. The supply chain must also have a fast design-to-delivery cycle, and likely relies on close supplier relationships with specialized suppliers who trust each other, and are used to working together.

As the above examples illustrate, managers must carefully design supply chain strategies appropriate for the company’s customer value proposition. If any aspect of the customer value proposition changes, the supply chain strategy may need to be adjusted accordingly. For example, if, as it often happens, a new product becomes mainstream and develops over time the characteristics of a functional product, the supply chain strategy would need to switch from responsive to efficient.

With the correct strategy in place, the next step is to design, build and manage the system that will deliver the promised value.

A Model for Customer Value Creation

If you ever want to start a new business, you will absolutely need three things: (1) money, (2) customers and (3) a system for producing and delivering products to customers. As a budding entrepreneur, you can outsource many tasks such as accounting, IT or HR, but you should maintain direct control of the above three core components of your business.

You can learn about the first two in your finance and marketing classes. This textbook is about the third one. Operations and supply chain management (which we refer to in this book as ‘the business behind the business’), is about the set of processes that will enable your company to turn the promised customer value proposition into actual value. You can have unlimited money, and many eager customers, but unless you have a system for delivering value, your company will flounder. That’s why operations and supply chain management is sometimes referred to as the “value creation engine of the organization.” Operations and supply chain management is where the rubber meets the road.

In this section, we briefly discuss the Supply Chain Operations Reference (SCOR) model, a model that was created in response to the growing need for a common language and structure to design and manage increasingly complex value creation processes across industries.

The SCOR model was developed in 1996 by the Supply Chain Council (SCC)—a global non-profit organization formed by industry leaders to create a standard framework for evaluating and improving supply chain performance. In 2014, the SCC merged with the American Production and Inventory Control Society (APICS), later renamed the Association for Supply Chain Management – ASCM, which continues to maintain the SCOR model.

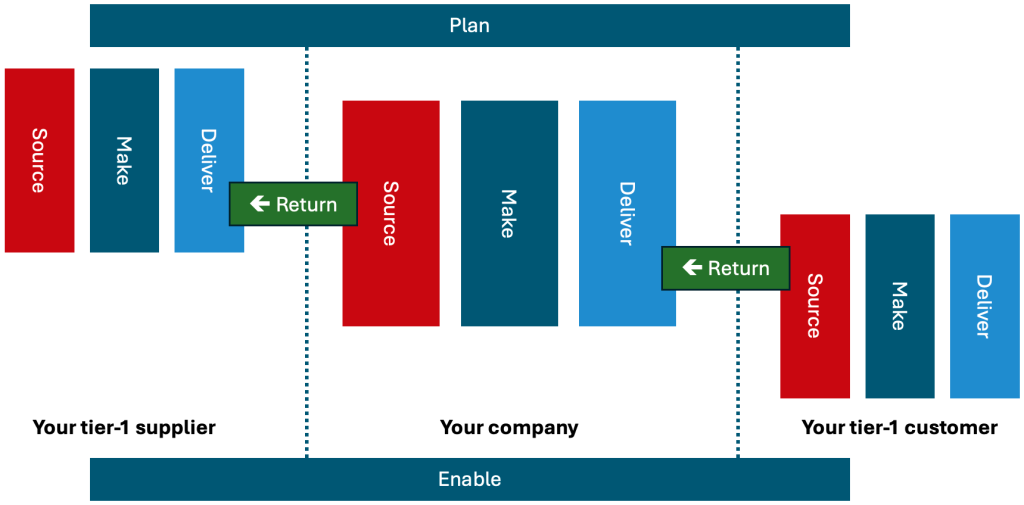

The model was designed as a process-based framework that maps out supply chain activities into five core management processes: Plan, Source, Make, Deliver, and Return, later expanded to include Enable. The SCOR processes direct your company’s internal and external supply chain operations. Internally, your company needs to coordinate the process of fulfilling a customer order among the departments involved. The order might have started in marketing and sales, before going to the accounting department for credit verification. Assuming the products are made to stock, the order is then transferred to logistics, where products will be picked, packed and shipped to the customer. If for any product the inventory falls below a predefined level, the purchasing department will be notified to place a purchase order to the supplier to replenish the stock so that the company is ready to fulfill the next order.

Externally, your company also needs to coordinate processes with supply chain partners. Specifically, your company’s Source and Return activities interact with your supplier’s Deliver and Return activities; whereas your Deliver and Return activities interact with your customer’s Source and Return activities as illustrated in Figure 2.2.

This textbook covers the entire span of the SCOR model. Each of the six core processes is briefly described next:

Plan

The Plan process involves coordinating resources, balancing supply and demand, and setting supply chain policies. It includes demand forecasting, inventory planning, capacity planning, and aligning financial and operational goals. Planning ensures that all other processes operate efficiently and effectively, minimizing financial and environmental costs while meeting customer needs. We discuss these activities in more detail in Chapters 5 through 8.

Note that we often refer to efficiency and effectiveness in this textbook. What do we mean by them? Efficiency is using the least amount of resources (time, money or effort) to reach a goal, and is often associated with cost or lead time minimization. Effectiveness is achieving the desired result or outcome, or simply meeting your goals. Peter Drucker once proposed the following play on words, which helps distinguishing between the two: “efficiency is doing things right;” whereas “effectiveness is doing the right things.” One could also say that effectiveness is about what needs to be done, whereas efficiency focuses on how things are done. That’s why they often go together.

Source

Sourcing is also called purchasing or procurement. It covers the acquisition of goods and services to meet planned or actual demand. It includes selecting suppliers and developing supplier relationships, ordering and receiving materials, managing inventory, and ensuring quality and compliance. The goal is to secure inputs cost-effectively and reliably (or one could say efficiently and effectively) to support production or fulfillment. Fundamental activities related to sourcing are presented in Chapters 3 and 4.

Make

Make refers to all activities related to manufacturing or producing goods and services. It includes production scheduling, managing work-in-process, assembling, packaging, and final product testing. These processes focus on efficiency, quality control, and meeting planned output levels. Together they constitute the operational core of any business, and are often referred to as ‘production’ or ‘operations’. These activities are covered in Chapters 9 through 11.

Deliver

Deliver involves all steps from order management to product delivery, and is often called logistics. It includes processing customer orders, warehousing, transportation, invoicing, and managing distribution networks. The aim is to ensure products reach customers accurately, quickly, and cost-effectively. Basic concepts in delivering are presented in Chapter 12.

Return

Return manages the reverse flow of products from customers back to the retailer or manufacturer. This includes handling customer returns (defective, excess, as well as end-of-life goods) and returning materials to suppliers. Key tasks are receiving, inspecting, authorizing returns, and restocking or disposing of goods, aiming to minimize disruption and maximize value recovery.

Enable

Enable supports the other five processes through infrastructure, data, governance, and compliance. It includes managing technology, human resources, business rules, risk management, and performance measurement. This process ensures the supply chain runs smoothly, adapts to change, and aligns with strategic goals. Activities in this area are introduced in Chapters 13 and 14.

In summary, the core management processes and associated resources of the SCOR model allow companies to:

-

Benchmark performance, that is, to measure and compare their performance against a standard, best practice, or competitor using the SCOR metrics to identify gaps,

-

Identify best practices that can be adopted to fill those gaps, and

-

Ultimately, align their supply chain operations with the business strategy.

Hopefully, the SCOR model will help you manage the core business processes that you will be responsible for as you embark on your career.

The SCOR model is widely adopted across industries, from manufacturing to services, and is regularly updated to adapt to changes in the business environment. One such change is the emergence and growing reliance on digital technologies to support or automate supply chain processes. These new technologies include autonomous mobile robots, autonomous vehicles, delivery drones, real-time inventory management solutions, or advanced automated storage and retrieval systems, to name a few. In response to recent trends in supply chain digitization, ASCM has developed a new set of SCOR standards known as the SCOR Digital Standard model.

Simulating Chaos: Lessons from the Beer Game

Across all six SCOR processes, effective collaboration and communication with supply chain partners are absolutely critical to business success. This is because the competition in the market place is not between individual companies, but between entire supply chains. For example, the Walmart supply chain competes against the Amazon supply chain. Walmart alone could not fulfill its mission to “help people save money and live better.” It needs all the companies in its supply chain to work together to minimize costs, eliminate waste, and speed up the flow of products. This requires all supply chain members to collaborate and communicate with each other and with Walmart.

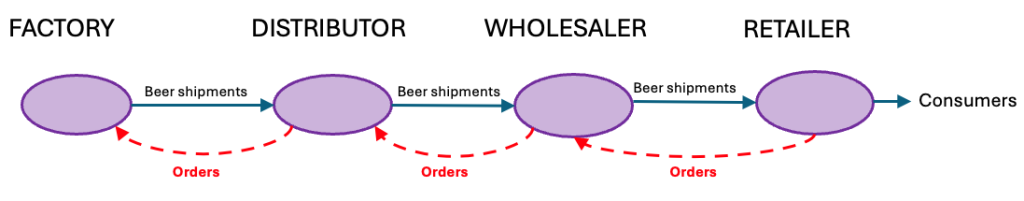

The importance of effective collaboration and communication in SCM is one of the main lessons from the Beer Game, which you will play in this class. The Beer Game simulates a supply chain that produces, distributes and sells beer. That supply chain consists of four companies: (1) The factory (in this case a brewery) produces crates of beer; (2) The distributor transports the crates from the factory to the wholesaler’s warehouse; (3) The wholesaler keeps inventory of beer close to the market, and fulfills the retailer’s orders for beer; and (4) The retailer sells beers to consumers.

You will be in charge of one of the four companies, and other students in your class will manage the other tiers. The game is played over multiple periods. At each period, you must decide how much beer to ship to your downstream customer, and how much beer to order from your upstream supplier to replenish your stock. For example, if you are assigned the role of distributor, you ship products to the wholesaler and place orders to the factory. Other identical beer supply chains, each managed by four students, will compete with you, and the supply chain with the lowest cost at the end of the game wins.

A key lesson from the Beer Game is that poor communication among supply chain members leads to chaos. Without communication, it’s very difficult to keep inventory where it is needed. The result is huge inventory levels or prolonged periods of stock-outs, all of which lead to skyrocketing costs.

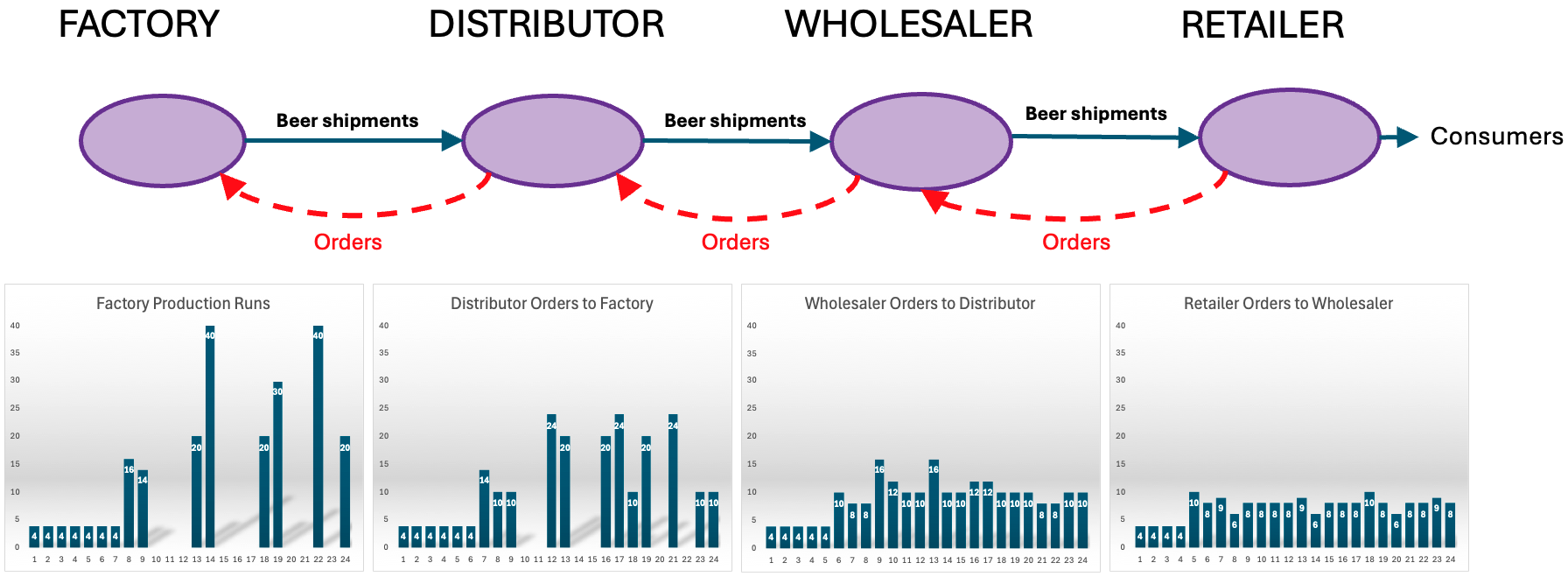

The Beer Game also reveals another phenomenon that has been observed in real-world supply chains: an increase in the variability of orders as one moves up the supply chain. This means that if orders placed by the retailer vary from period to period, orders placed by the wholesaler vary more, and orders placed by the distributor and the factory even more still. This phenomenon is called the “bullwhip effect” because the pattern of orders along the supply chain looks like the cracking of a whip.

Figure 2.4. shows the outcome of an hypothetical Beer Game over 24 periods. The bar charts represent the quantities ordered by each member of the supply chain. Starting at the end of the supply chain, nearest to the customers, you can see that the retailer’s orders are regular. An order is placed every period, and the quantities range between 4 and 10. Moving up one tier, we go to the wholesaler chart. The wholesaler also orders every period, but the quantities are larger, with the majority of them between 8 and 16. At the distributor level, the scale changes. Orders vary between 0 and 24, and we begin to see gaps in orders, including six periods during which no orders are placed. This is an indication that the variability of orders is increasing as one moves upstream, even as the total quantity ordered is about the same at each tier of the supply chain. The situation is worse at the factory level: Orders vary widely from period to period.

Variability is bad news for supply chains, in general, but especially for manufacturing plants. Manufacturing managers prefer even, steady flows, which allows them to produce roughly the same amount of products every day. By doing so, they can optimize the utilization of their expensive machines, and keep workers busy. Hugh variations in orders force them to stop and go and stop again and go again, or carry huge amounts of inventory. In either case, their costs go up, which means that customers will have to pay higher prices.

The pattern seen in the game has been observed in real-world supply chains. For example, Proctor & Gamble (P&G) discovered the bullwhip effect in their diapers operations. P&G managers knew that demand for diapers was steady and predictable. The number of babies does not change much, and babies need the same quantity of diapers day in and day out, even in the summer, on weekends, or during holidays. Diapers are a functional product. P&G managers could not understand why the orders their factories were receiving from Walmart varied so much. They investigated and found that the lack of coordination in the supply chain was causing the bullwhip effect. When you play the Beer Game, think about the information you would like to have, who has that information, and what processes you could put in place to better coordinate the supply chain with that information.

Careers in Supply Chain Management

People often overlook what happens in the supply chain until something goes wrong. It’s similar to basic necessities like water or electricity that we tend to take for granted. The critical role of SCM became more apparent during the COVID-19 pandemic, when demand and supply mismatches were exceptionally severe and widespread, and the world ran out of many basic necessities. Suddenly, SCM, which was previously seen as an obscure and dull topic, took center stage in the news and everyday conversations. This interest in SCM has continued even after the pandemic, fueling the growing demand for qualified supply chain professionals in every industry.

You might think that the cavernous and noisy logistics center of creaking metal and flickering lights located between the rail yard and the highway interchange is not appealing to bright business graduates like you, who are seeking exciting careers. However, the truth is that there are many truly fascinating, well-paying jobs in the supply chain, where you could make a difference. Like many students before you, you may not realize that your future could lie in the supply chain! Indeed, it is common for those who major in fields other than SCM to find themselves pursuing careers in supply chain management later on. Perhaps they grew weary of the office routine and wanted a piece of the action. Keep in mind that most of a company’s assets (its people, equipment and buildings) are housed in the supply chain, which is also where many rewarding jobs are located.

The fact is that job candidates with a bachelor’s degree in supply chain management or a related field are in high demand, and will continue to be for the foreseeable future. Table 2.2 presents recent statistics from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics on the job prospects of selected careers in SCM for which a bachelor’s degree is a required or preferred qualification for employment. In Table 2.2, the job outlook column gives the projected percent change in employment from 2023 to 2033, and the employment change column the projected numeric change in employment over the same period. The bottomline is that the US will need tens of thousands of additional supply chain professionals in the immediate future.

| What they do | 2024 Median Annual Pay | Job Outlook (2023-2033) | Employment Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Logisticians | Analyze and coordinate an organization’s supply chain. | $80,880 | 19% (Much faster than average) | 45,800 |

| Buyers | Buy products and services for organizations. | $79,830 | 7% (Faster than average) | 41,400 |

| Operations research analysts | Use mathematics and logic to help solve complex issues. | $91,290 | 23% (Much faster than average) | 28,300 |

| Project management specialist | Coordinate the budget, schedule, staffing, and other details of a project. | $100,750 | 7% (Faster than average) | 69,900 |

There are many different kinds of jobs in the supply chain, where individuals like you, with their unique skillsets and personalities, can express their talents. There are also positions at every level of the organization from entry-level positions as buyers, materials analysts or logistics specialists, to mid-level management and senior-level jobs. In fact, working in the supply chain can prepare you for C-level positions because you will know the business from the inside out, and understand it very well.

A balance of technical and people skills is an advantage because the types of solutions supply chain managers have to create and implement not only require a solid technical background; they also require the ability to work well with people. If you’re wondering if SCM is the right major and career path for you, ask yourself the following questions:

- Do you like working with people? Supply chain professionals spend a lot of time working with suppliers, customers, and colleagues in other departments to make sure the processes are in place, and working as they should, to meet the needs of the end customer.

- Do you like solving problems? There is never a dull day in SCM. Even with the best plans, problems of all kinds keep happening, and usually need to be solved quickly. Systems must be put in place to make the supply chain robust, and prevent the same problems from reoccurring.

- Do you like when your work gets noticed, and you feel you’re making a difference? Supply chain professionals are responsible for meeting the needs of customers, who are the only persons putting money in the supply chain. You can make a difference by ensuring that the money keeps flowing in, and that customers won’t take their business elsewhere.

- Would you rather not sit at a desk all day? The people you work with are probably not working in the cubicle next to yours.

- Do you like to travel occasionally? If you work in SCM, you can live in your favorite city, and still enjoy the thrill of traveling occasionally to visit your suppliers or customers. Even if your company is small, chances are you have supply chain partners in exotic places in South America, Asia, Europe and elsewhere.

- Do you like a fat paycheck? Who doesn’t? As the data in Table 2.1. shows, supply chain professionals can afford a good living.

- Would you like to work in the you-name-it industry? Every company is part of at least one supply chain, and has operations and supply chain functions, even if they call it something else.

If the answer to most of the above questions is yes, then you should explore careers in SCM. Talk to someone you know who works in the supply chain, or meet with your SCM professor.

Discussion Questions

- What are the customer value propositions of Netflix, Dell Computers, and Zara?

- Think about your experience at your current university. What is an example of each of the five value dimensions in this context?

- Going back to the opening story at the beginning of this chapter, identify where customer value is added or lost across the six SCOR supply chain processes.

- Illustrate how each SCOR process contributes to the end-to-end flow of Electronic Engine Controls (EEC).

- How would you handle the current EEC situation if you were John?

- What does it mean to complete a homework assignment efficiently? and effectively?

- What is an example of a functional product (other than the examples listed in this chapter)? and an innovative product?

- Which SCM career path interests you most? Why?

Media Attributions

- Dimensions of Customer Value © François Carrier is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- The core supply chain processes © Association for Supply Chain Management adapted by François Carrier is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Supply Chain Structure in the Beer Game © Nancy Tomon adapted by François Carrier is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Bullwhip Effect in the Beer Game © François Carrier is licensed under a CC0 (Creative Commons Zero) license

- Note that we use the term 'product' generically to represent the company's output whether it is a physical good or a service. ↵

- Simchi-Levi, D. (2013). Operations rules: delivering customer value through flexible operations. MIT Press. ↵

- Meyer, C., & Schwager, A. (2007). Understanding customer experience. Harvard Business Review, 85(2), pp. 116-126. ↵

- Lafley, A. G., & Martin, R. L. (2013). Playing to win: How strategy really works. Harvard Business Press. ↵

- U.S. Census Bureau ↵