10 Business Process Management

How Work Gets Done

Evan Barlow

Learning Objectives

- Understand business processes

- Visualize business processes with block diagrams

- Analyze business processes using qualitative and quantitative tools

- Understand how and why to manage capacity and demand

- Understand the intuition of service business process analysis

Introduction

Carla Rivera, the Chief Operating Officer (COO) of Bottle’s Neck Productions, stood before a group of creative directors in the studio’s sunlit conference room. The air was a mix of tension and curiosity. Bottle’s Neck Productions, known for its award-winning films, had hit a peculiar crossroads. While their artistic endeavors won unprecedented acclaim, they were dangerously close to being bankrupt. Carla’s mission? To introduce the concept of business process management (BPM) to a team that lived for artistry, not dollars.

This chapter is built around Carla’s efforts to guide Bottle’s Neck Productions through the fundamentals of Business Process Management, showing how it can empower creativity while addressing the operational realities of running a successful business.

What Are Business Processes?

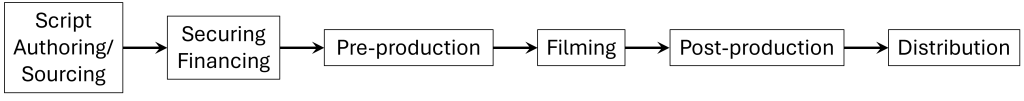

Carla started with the basics: “A business process is a series of steps—inputs, activities, and outputs—that work together to create value. For us, it’s everything from securing financing to distributing our films.” She illustrated this idea with a diagram on the whiteboard:

She explained the core components of a business process:

- Inputs: units that flow through the process and the resources that complete process activities.

- Activities: Tasks carried out along the process to generate final product or service.

- Outputs: The final products—movies ready for audiences.

Carla emphasized a key point: “Processes are the building blocks of our studio. Everything we do is part of some process that supports the business. And business success is exactly what funds our ability to keep doing what we love. And if we can’t keep this company afloat, none of us will ever be able to get a job in the entertainment industry ever again.”

Why Processes Matter

The creative directors were skeptical. One stood up and asked, “Won’t focus on these processes stifle our creativity?” Carla smiled. “Not necessarily. Right now, we have some of the best people on the planet. We have top-of-the-line equipment. But we don’t want you to waste your time and talents. If we can understand and improve our processes, your creativity won’t be held back by our capacity in some other area of the business. I want to enable you to produce even more movies without sacrificing an inch of artistry. Your creativity and artistry are loved by viewers all over the world. When they’ve finished watching one of your movies, you leave them thirsting for more. They want nothing more than to see what you’re going to do next. By understanding and managing our business processes, we’ll be able to give our viewers more of what they love while allowing you to do more of the work you love.”

Visualizing Business Processes

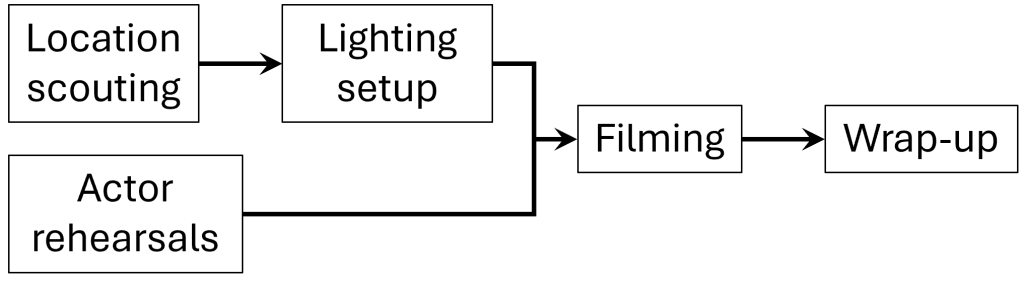

“Now,” Carla said, “let’s diagram one of our processes—say, a scene shoot.” She handed out papers and markers, encouraging the team to sketch a block diagram that showed the necessary activities and the resources required to do each activity.

Steps to diagram:

- Location scouting

- Lighting setup

- Actor rehearsals

- Filming

- Wrap-up

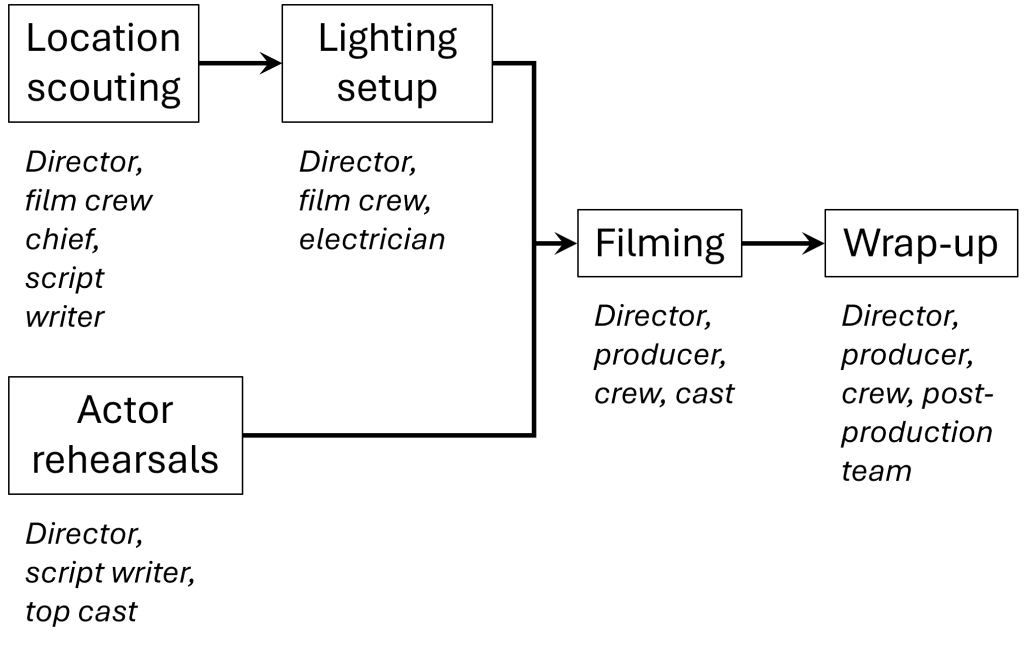

She then introduced the concept of sequential and parallel activities. “Certain steps must occur one after the other, while others can happen simultaneously. Understanding this helps us avoid unnecessary delays. For example, typically we wait for actor rehearsals until after the lighting is completely set up. In most situations, however, actors can begin rehearsals virtually even before a location is selected. So a process for most scene shoots could look something like this,” she said, showing them the diagram shown below.

“For any process, even a simple visualization like these block diagrams can help us see what currently do so we can figure out ways to improve.

Understanding the resources in the process activities is also important. This is particularly important for all resources that are required for two or more different activities. They have to split their time between multiple different activities; and we have to make sure that all of the resources required for an activity are coordinated so that they’re all in the right place at the right time. This resource information can be added to these simple block diagrams.”

Understanding and Identifying Bottlenecks

Carla picked up a bottle of water from the table. “This,” she said, holding it high, “is why our studio is named Bottle’s Neck Productions. At the bottle’s neck, all the water in the bottle converges to a single area just like all of our creative talent converges to produce outstanding movies. The water in the bottleneck also becomes turbulent, often mixing and churning in unpredictable, unexpected, and yet beautiful ways. This turbulence is just like our creative processes and the complexity of the stories we create in our motion pictures.”

“Unfortunately,” continued Carla, “bottlenecks have a downside that has recently described our production studio. Bottlenecks slow everything down. We don’t want this aspect of bottlenecks to continue to describe our studio. So let’s figure out how to identify the bottleneck in our film production process.”

She asked a question: “If you decided to produce twice as many movies per year, what resource would prevent you? Whatever resource you identified is the bottleneck. We are constrained from increasing the number of movies produced per year, or our annual movie throughput, by the bottleneck resource. The bottleneck is not an activity – it’s a resource. It’s not even the resource that is required for the most time during the production process. The bottleneck is the resource that prevents us from making even more movies.”

“That’s easy!” shouted one of the creative directors, “The bottleneck is definitely the cast! I can’t tell you how often I have to wait for all the necessary cast to arrive on set and get ready to shoot!”

Carla thought a minute and replied, “Okay, that’s a really good insight that candidates for bottlenecks are resources that we have to wait for. But remember that the bottleneck is a resource that prevents us from producing more movies in a year. If the bottleneck is the cast, then why can’t we produce more movies per year when there’s almost no overlap between the cast members of two different movies? Would we be able to produce twice as many movies per year and just pay roughly twice as many cast members?”

A business director made a guess: “Maybe the film crews are the bottleneck. After all, each film crew can only be on one movie at a time, and we don’t really hire outside film crews like we do with cast members.”

Carla replied, “That’s also a really great insight. All of our resources face constraints. One of the constraints for our film crews is that they can only work on one movie at a time. Another constraint is that we only have a limited number of film crews. And that’s really the key to identifying the bottleneck! Think about each resource we need to produce movies. For each resource, think about the maximum number of movies we can produce in a year given the constraints facing that resource. As you think about the constraints facing that resource, ignore the constraints facing all other resources. For example, consider the film crews as a resource. Pretend that we dramatically increase the amount of every other resource but film crews – so pretend we double the number of cameras, buildings, directors, producers, budget dollars, etc. but we keep the same number of film crews. How many movies will we be able to produce in a year? After we go through each resource in that way and figure out the maximum number of movies each resource can produce in a year, we find the resource with the lowest maximum number of movies. This resource with the lowest maximum number of movies per year is the bottleneck! And the maximum number of movies that the bottleneck resource can produce in a year is the capacity of the entire production studio! That’s why it’s so critical to identify the bottleneck resource. Increasing capacity for any non-bottleneck resource will do almost nothing to improve our ability to produce more movies in a year.”

The entire team started going through all of the resources required for making a film: the writers, approval committee, investors, film crew, film equipment, casting crew, film cast, producers, directors, logistics staff and leaders, post-production editing team, marketing personnel, and every other resource they could think of. A few suggestions came up and consensus started building around the financing and investors as bottlenecks. Carla asked, “What is it that makes you think that the financing and investors are the bottleneck for our studio?”

One members of the team explained, “Almost every single resource we have often finds itself waiting for the resources involved in the step before it. All of them think that those resources are the bottleneck, but each of those resources is often waiting for the resources involved in the steps prior.”

Another team member piped in, “Some of the resources see a build-up of movies at times. For example, the post-production teams sometimes have more work than they can handle. So, while they were a likely candidate for the bottleneck, they also reported that they sometimes wait for the next movie to finish filming.”

A business director for the post-production team stepped up and said, “We feel like we could handle 30% more movies coming through each year before we get to the point that we’re always busy and never idle.”

Carla thought about their suggested bottleneck for a moment. “Okay, you’ve got some really good evidence suggesting that the investors (who are essentially the approval committee) are the bottleneck. But it’s a bit unfair since they’re not here at the meeting. What do you think they would say if they were here?”

“I can tell you that,” one writer chimed in. “They frequently tell us writers that the scripts aren’t good enough. Or they insist on major revisions before reviewing the proposal again and deciding on a path forward. Sometimes they insist on revisions and then end up rejecting the movie pitch anyway. It’s a huge waste of time and effort for us writers.”

“Do they have to evaluate a lot of scripts? And do the writers often have to wait a long time before getting a response from the approval committee?” Carla asked.

“Yes,” the writer responded. “From what I understand, they complete the decision making process for each movie in less than a week. But it often takes a month or more before we get any response. And the time it takes seems to be getting longer and longer over time.”

“Okay,” said Carla, “let’s see if we can come to some consensus about the annual capacity of each resource.” The team spent the next several minutes coming up with the following table to find the resource with the lowest annual capacity.

| Resource | Unit Annual Capacity (films per year) |

Number of Units Available | Resource Annual Capacity (films per year) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Writers | 1 | 25 | 25 |

| Approval Committee | 11 | 1 | 11 |

| Film Crews | 2 | 10 | 20 |

| Film Directors | 2 | 9 | 18 |

| Film Producers | 6 | 4 | 24 |

| Acting Cast | 1 | Practically unlimited | Practically unlimited |

| Production Equipment | 3 | 14 | 42 |

| Technician Crews | 6 | 5 | 30 |

| Post-Production Teams | 2 | 11 | 22 |

All of this was very convincing evidence. From the table, it looked like the approval committee would need to increase their annual capacity up to at least 18 films per year before another resource became the bottleneck. She knew she needed to dive in deeper and figure out what could be done. She called a friend who was in the approval committee meetings and asked about the review and approval process. After a brief discussion, Carla knew all she needed to. She had identified the exact bottlenecks: the Chief Financial Officer (CFO) and the Head of Production. Both of them insisted on being present and fully involved in every single review and approval. However, their schedules often conflicted; so meetings had to be delayed. Furthermore, it didn’t seem that either of them had these meetings as a high priority – the CFO had other duties he frequently deemed more urgent and the Head of Production often preferred to be out visiting film sets and wining and dining top Hollywood acting talent.

Summary: How to identify the bottleneck:

- Monitor Waiting Times: Look for resources or tasks where others frequently have to wait. Extended delays or queues at a specific stage often indicate a bottleneck.

- Evaluate Idle Periods: Check if downstream resources are often idle, waiting for input from an earlier stage. This suggests a bottleneck is slowing the flow.

- Assess Workload Build-Up: Identify areas where work accumulates, such as unfinished tasks or backlogs, which can signal a bottleneck in the process.

- Analyze Utilization Rates: Resources that are consistently overworked or operating at maximum capacity may be bottlenecks, particularly if others have spare capacity.

- Examine Decision-Making Delays: Processes that depend on approvals or decisions can face bottlenecks if key decision-makers are unavailable or unresponsive.

- Track Cycle Times: Measure the time it takes for tasks to move through each stage of the process. Significant increases in cycle time at one stage can highlight a bottleneck.

- Consider Variability in Demand: Sudden spikes in workload at specific stages can create temporary bottlenecks, highlighting areas that need better capacity management.

- Gather Feedback from Teams: Ask team members about pain points. They can provide valuable insights into which resources or steps are most often delayed.

- Analyze Throughput: Compare the output of each stage. A bottleneck often has the lowest throughput, restricting the overall process capacity.

- Use Visual Tools: Tools like process flow block diagrams can help pinpoint stages where delays or inefficiencies occur.

Eliminating Bottlenecks

Carla decided to apply the principles of the Theory of Constraints to tackle the bottleneck that had been slowing their film production pipeline. Her first step was to identify the constraint, which turned out to be the film approval process. This stage was consistently overloaded, with projects piling up and causing either delays or idleness across the other stages of production. Armed with this knowledge, Carla gathered her team to brainstorm solutions.

The Theory of Constraints states that the step after identifying the bottleneck is “exploitation” — making the most out of the identified bottleneck without major investments. Carla met with the CEO, the CFO, and the Head of Production to talk about prioritizing the approval process. She pointed out that they could be producing several more movies each year if they could alleviate the approval committee’s bottleneck status. She asked the CFO and the Head of Production if they had any ideas about how to increase the approval process throughput. They both agreed to prioritize the film approval process. But they also said that there are often calendar items that cannot be rescheduled. They asked Carla if there’s anything else that could be done.

Carla said, “Our next step is to subordinate the rest of the film-making process to the bottleneck (the film approval process). We’re going to form a committee of writers, directors, and producers to perform a pre-approval check. That way, the actual approval committee doesn’t have to waste their time with as many film pitches that won’t actually ever be turned into films. Hopefully, the approval committee will find themselves approving almost all film concepts that come to their desks.”

Carla continued, “We’re also going to try to elevate the constraint. This means that we’d like to increase the number of films that can be reviewed in a year. Would you be willing to allow someone that works for you to represent you on the film proposals that get overwhelming support from the pre-approval committee? That way, you don’t have to spend your limited time on film proposals that are almost guaranteed to be approved for production. Your expertise is really most valuable for the film proposals that are “borderline cases” from the financial perspective, the production/creative perspective, or both.” Both the CFO and the Head of Production agreed to allow a direct report to act on their behalf, though both expressed the feeling that they loved reviewing the “guaranteed-to-be-approved” film proposals because of the energy and excitement that came with them. They also understood, however, that the needs of the studio took priority.

Carla went back to her team of creative and business directors to give them the good news. They were thrilled that they would be able to create more movies and really liked the idea of being able to participate in the pre-approval process for film proposals. Carla warned them, “With the changes we’re making to the film approval process, the studio’s capacity will increase until we hit another resource’s capacity. In other words, we’re likely to have a different bottleneck going forward. So keep your eyes open for the signs and symptoms of bottlenecks. If you think you see a bottleneck, let me know so that we can address it.

In the months following the changes to the approval process, the results were apparent. Throughput for the year was expected to increase by 20%. Films moved smoothly through the production pipeline. Carla’s application of the Theory of Constraints not only resolved the immediate issue but also prepared the company to handle the projected growth in the entertainment industry.

Summary: Address an Identified Bottleneck

- Identify the Bottleneck: The first step is pinpointing the part of the process causing delays, as it restricts overall capacity.

- Exploit the Bottleneck: Maximize the efficiency of the identified bottleneck without significant investment. For example, prioritize tasks to make better use of resources in this critical stage.

- Subordinate Other Processes: Align all other parts of the process to support the bottleneck. This might involve creating preliminary checks or filters to reduce unnecessary workload for the bottleneck stage.

- Elevate the Bottleneck: Increase the capacity of the bottleneck by adding resources or delegating tasks. For instance, involve additional team members or representatives to handle simpler cases, freeing core decision-makers for more complex issues.

- Monitor for New Bottlenecks: Once the bottleneck is addressed, another bottleneck may emerge elsewhere in the process. Stay vigilant.

The Story of Throughput, Inventory, and Cycle Time

Carla scheduled a critical meeting with the CFO to discuss an essential but overlooked aspect of their newfound success: the financial implications of the increased throughput. As she settled into the chair across from the CFO, she began with measured clarity, “You’ve seen the quarterly reports—our throughput has grown by 20%, and the studio is buzzing with activity. This is, of course, phenomenal news. But I want to make sure we’re prepared for the financial ripples that come with this change.”

The CFO nodded, intrigued, as Carla leaned in, her tone shifting to one of caution. “It’s important that we consider Little’s Law in this context. Throughput, inventory, and cycle time are all interconnected, and increasing throughput isn’t as simple as turning a dial. As throughput doubles, it’s likely that our inventory—whether that’s unfinished scripts, production queue items, or even post-production edits—will grow unless we decrease cycle time.”

Carla pulled out a whiteboard marker and quickly sketched the equation:

Average Inventory = Average Throughput × Average Time in System

“Let’s break this down. If we aim to double our throughput, there are two ways to achieve it: we either increase inventory, which means we’re holding more films in progress, or we reduce cycle time, speeding up each production. Both have financial consequences.”

The CFO furrowed their brow. “Increasing inventory of movies in-process — I’m not sure we can handle that. All of these films require capital. I’m not sure we can even free up the funds for continued growth of throughput. What about decreasing cycle time?”

“Reducing cycle time means investing in efficiency,” Carla explained. “By addressing bottlenecks, we’re already seeing some improvement, but cutting the cycle time in half doesn’t seem feasible. We could upgrade equipment, hire more staff, or adopt new technologies to accelerate production. While this reduces the time films spend in progress and allows faster delivery to customers, it also demands upfront investment and continuing expense. And let’s not forget that rushing processes can sometimes compromise product quality, which affects our reputation.”

The CFO tapped a pen thoughtfully on the desk. “So, what’s our best course of action?”

Carla looked directly at the CFO and was glad they had a good working relationship. “We’re going to do everything we can do reduce cycle time at low cost. And we’re going to upgrade and standardize our equipment and processes. But we estimate we can only reduce cycle time by about 10%. All additional advances in throughput will represent higher in-process inventory – we’ll be working on more films at the same time.”

She continued, “How fast can we increase our throughput without putting too much strain on the company finances?”

The CFO thought for several minutes, clearly running through all important financial aspects of the business. “We’ll need to model this carefully to be sure, but I’m confident that we’ll be safe if we grow our throughput and inventory at a pace of around 10% per year going forward.”

Carla nodded. “I’m so glad you’ve got the vision to see the importance of the growth we’re driving; and I’m even more glad to have your expertise to make sure we grow wisely and sustainably.”

Managing Demand to Meet Business Capacity

Next Carla went to meet with the Chief Marketing Officer (CMO) – they needed to be on the same page so that the target audiences and the advertising strategies aligned with the evolving production operations.

Carla entered Antonio’s bright, open office. Antonio, the CMO, had a desk littered with mockups of promotional posters for upcoming films. As she settled into a chair, Antonio looked up with a warm, inquisitive smile. “Carla, I hear there’s some big planning coming out of your department. What’s the latest?”

Carla leaned forward, her hands folded on the table. “Antonio, I wanted to discuss how our production strategies are evolving and ensure we’re completely aligned on our shared objectives. Right now, we’re hitting a 20% increase in throughput, and we’re targeting a steady 10% growth in throughput annually going forward, which means producing more films and doing so faster. But that also means we’ll have more movies in progress at any given time. From your side, it’s vital that we manage demand to match this growth — both in terms of audience expectations and the timing of releases.”

Antonio nodded thoughtfully. “I see. That’s a big shift, but it’s exciting. We’ll need to be strategic about how we position these additional films. Overcrowding the release calendar could dilute the impact of our campaigns or confuse audiences. We’ll want to stagger releases carefully, perhaps even leaning into seasonal trends.”

Antonio’s face turned to concern as a thought occurred to him. “What’s wrong?” Carla asked.

“Well,” Antonio started, “with an increasing portfolio of movies, we’re going to see some of them vastly outperform others; and with an increasing diversity in genres, we may be able to consider extending the film concept lifecycle to fill gaps between releases. I’ve pitched the idea to the company in the past, but the Head of Production has always shut me down. What about film franchises? You see, in the past, the Head of Production has always said that’s not the domain where our creative expertise lies; but it might align with what you’re trying to do with operations.”

“You see,” Antonio continued, “with movie franchises – think Mission Impossible, James Bond, Harry Potter, Star Wars, Terminator, Predator, Jurassic Park, The Godfather, Tom Clancy’s works, and even Toy Story and Twilight – we get an almost automatic audience. Sequels, prequels, offshoots, branches into other media like video games, TV series, and even animation. Viewers who loved one movie will return for everything else. Furthermore, franchises allow you to shorten some of the production steps like casting and authoring, so franchises could help you shorten your cycle time! On top of that, franchises give us an opportunity to temporarily resurrect previous releases as viewers gear up for the latest installment, helping us manage demand while generating revenue for advertising new releases.”

“Holy crap!” Carla exclaimed a lot louder than she intended. She immediately put her hands over her mouth and apologized, “Sorry, that outburst was really unprofessional. Really, the outburst is just a compliment – that’s such a great idea! That would help financing with the risk profile too. Let’s get moving on this. I hope we don’t have to steamroll the Head of Production, but we will if we have to – we can’t let this studio fail on our watch, especially when we have ideas like this.”

Service Business Processes

Now it was time for Carla to work on their streaming service.

A streaming service exemplifies the characteristics of a service, as it is inherently intangible, perishable, and reliant on real-time interaction with customers. Unlike physical products, which can be produced, stored, and distributed in advance, services like streaming must be delivered simultaneously with their consumption. This means that the quality and availability of the experience depend heavily on factors such as server capacity, network stability, and customer support. Moreover, services are inherently variable due to the diverse nature of customer needs and preferences, requiring constant monitoring and adaptability to ensure satisfaction. While films can be produced and distributed, the streaming platform serves as the medium through which those products are delivered, emphasizing the critical role of operational efficiency in maintaining a seamless and engaging customer experience.

Carla understood that service processes, like the ones that keep the streaming platform running, can generally be categorized into multiple types based on 1) the degree of human labor relative to capital requirements, and 2) the level of interaction/customization offered to customers.

| Service Process Categorization Matrix | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Human Labor : Capital Ratio | |||

| Low | High | ||

| Interaction / Customization | Low | Service Factory Service factories focus on efficiency through highly standardized processes supported by significant technology and capital investment. These services typically aim for high throughput and consistent quality with minimal customer interaction. Example: Airlines |

Mass Service Mass services emphasize scale, focusing on delivering standardized services to a large number of customers. While labor-intensive, these processes minimize the need for specialized customization or extensive customer interaction. Example: Retail Banks |

| High | Service Shop Service shops provide more personalized services than service factories but still depend on specialized technology or capital assets. They may involve higher levels of customer interaction but are less labor-intensive. Example: Hospitals |

Professional Service Professional services involve highly skilled labor and extensive customer interaction to deliver tailored solutions. These processes are often time-intensive and require in-depth collaboration with clients. Example: Management Consulting Firms |

|

Managing Capacity and Demand in Services

Carla turned her focus to the challenge of managing capacity and demand for their streaming service. She knew that peak times, such as the release of highly anticipated films or franchises, could strain the system, leading to potential failures in service delivery. To address this, Carla proposed a multi-faceted approach.

First, she suggested implementing dynamic load balancing to optimize server usage during high-demand periods. By redistributing traffic across servers, they could prevent bottlenecks and ensure seamless streaming experiences for a wide variety of audience size. Additionally, Carla discussed the value of predictive analytics. “If we can analyze viewing patterns and anticipate spikes,” she explained, “we can prepare in advance—whether by scaling server capacity or preloading content closer to the edge of our network to reduce latency.”

Carla also wanted to influence the demand patterns, so she changed the subscription options. She created a “no-ads” subscription option and a “premium” subscription option. The streamers who didn’t subscribe to “premium” could only access premium content during off-peak hours. “Premium” subscribers could view any content at any time of day. With the different subscriptions, Carla was able to dramatically reduce usage during peak hours and increase usage during off-peak hours. This meant that Carla didn’t need as much server capacity. Carla also entered into a contract with a data center that could provide “overflow” server capacity for the rare occasions that Bottle’s Neck Productions’ own server capacity was insufficient.

By implementing these strategies, Carla was able to get their resources operating more efficiently and more profitable while improving the customer satisfaction.

Reducing and Managing Variability in Services

Carla turned her attention to reducing and managing the inherent variability of demand in the streaming service. She understood that variability in services could come from both fluctuating customer behaviors and fluctuating network conditions. To tackle these challenges, Carla proposed a series of strategies.

The first step was reducing unnecessary variability on their side. Carla standardized protocols and procedures for deploying digital assets across servers. Carla also made each streaming server appropriately flexible – she didn’t want one movie for each server or each server to have to store all movies.

Another focus was variability caused by external factors, such as internet speeds. Carla worked closely with her technical team to implement adaptive streaming technology that automatically adjusted video quality based on real-time bandwidth availability.

Through these efforts, Carla created a streaming platform that was not just resilient but also adaptable to the diverse and ever-changing needs of its audience.

Conclusion

This chapter underscores the importance of understanding and leveraging core principles of business process management to address challenges and drive success. Business process visualizations are valuable in dissecting complex workflows and identifying areas for improvement, ensuring that each step in the process aligns with bigger-picture objectives. Similarly, bottleneck identification and management offers critical insights into system limitations and provides actionable strategies to alleviate constraints, enabling smoother operations and scalability. The chapter also highlights Little’s Law, a fundamental framework for understanding the relationship between throughput, cycle time, and work-in-process inventory. By applying this principle, organizations can easily and effectively understand how changes in one area of the business might impact other aspects of the process and the business overall. Finally, the chapter presents some of the aspects of business process management that typically apply more to service and less to production processes. With service business processes, there is typically a much greater emphasis on managing variability since inventory is not available as a weapon to combat variability. In addition, there are slightly different approaches available for managing capacity and demand.

Media Attributions

- Illustrative Film-Production Process © Evan Barlow is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Serial and Parallel Process Steps © Evan Barlow is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license

- Serial and Parallel Process Steps w Resources © Evan Barlow is licensed under a CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution NonCommercial NoDerivatives) license