3 The Human Link: The Critical Role of Soft Skills in Supply Chain Management

Hugo Decampos

Learning Objectives

- Understand the basics of effective human relationships and the role of trust

- Understand the basics of team development and what differentiates high-performing teams

- Identify the key inter- and intra-firm relationships that involve supply chain management

- Understand how managing these relationships can lead to improved business outcomes

- Apply the principles in this chapter in creating a personal human relations improvement plan

Introduction

Business education across the world has greatly focused on the tools of the trade and how each function (marketing, finance, accounting, operations etc.) is run using those tools. A student majoring in business will therefore take such courses and will come out with a degree and a knowledge of tools and frameworks used in across the many functions of a business. One key element, however, that is greatly lacking in today’s business education is the relational skills needed to effectively run a business and coordinate the efforts of the many functions of a business. Additionally, since we are in a world of increasingly segmented and specialized business, these relational skills are also needed to better manage supply chains across varied geographies. Some refer to the technical tools of the trade as ‘hard skills’ and the ability to manage relationships as ‘soft skills’. Soft skills include the understanding of what drives successful human to human interactions, including skills in communication, empathy, emotional intelligence, team building, collaboration, negotiation and conflict resolution. Despite this terminology, there is nothing soft about ‘soft skills’ and by no means are they inferior to the ‘hard skills’ that are rigorously taught and tested in most of your business courses.

In supply chain management, where math and statistical software packages often optimize transportation routes, run analytics on demand patterns and inventory trends, the role of soft skills can be easily overlooked. While such hard skills and analytical prowess can set one apart in this data heavy field of business, the soft skills needed to create bridges of understanding and problem solving require mature and astute people management skills. Of all the functions in business, supply chain management has perhaps the greatest breadth in complexity of human interactions that need to be managed in order to get the job done. Supply chain management interfaces with almost every function within the company and then on top of this must also develop and maintain effective relationships with suppliers and customers in order to coordinate the operational flow of goods and services.

Despite the best of intentions and planning, a well designed supply chain does not operate autonomously. Even though complex forecasting and ordering systems have automated much of the tasks of detailed planning and control, exceptions and problems frequently arise in the world of supply chain management that require human beings to get involved to solve issues that arise. Supply chain management often must forge teams across company boundaries to solve these issues. Supply chain managers must therefore know not only how to manage teams within their own firm, but must also know how to create, manage, and optimize team efforts across firm boundaries with two or more companies. Supply chains are ultimately powered by people, and soft skills are essential to their success.

This chapter provides an overview of the soft skills needed for the successful supply chain manager and also introduces the concept of trust, which is the lubricant of supply chain relationships.

Beyond the Network: Why Soft Skills Matter in Supply Chain Management

Case study

Noah Lotte was living the dream! He had finished his undergrad studies in engineering and had gone on to grad school to get his master’s in business administration. Now with one year under his belt, he was an intern in the international supply chain group at the automotive giant, Lieutenant Vehicles (LV) helping manage the inbound flow of parts sourced internationally. If he played his cards right, the internship could turn into a full-time position helping manage one of the most international and complex supply chains in the world. Additionally, LV was running a management development program (participants were called ‘strategic MBAs’) that Noah could be a part of that accelerated a new hire’s career development launching the person into a supervisory role after one year and targeting a manager’s position in three years. This was the chance of a lifetime!

Noah moved to Michigan and threw himself into the work. After spending a few weeks learning about how LV manages its inbound supply chain of international production parts, Noah learned that the company decided to keep an arbitrary four-week safety stock of these inbound parts in a Michigan warehouse and that this four-week safety stock was a key variable in planning supplier ship schedules. The four-week safety stock levels for a vehicle program were calculated before the launch of that program and were based on pre-production estimates; this resulted in safety stock levels that would never change with fluctuating production levels throughout the program’s five-year life cycle. This policy, combined with overly-optimistic forecasting values resulted in extremely high and unnecessary levels of safety stock that filled the international parts warehouse with excessive inventory and resulted in significant financial losses due to obsolete inventory when programs ended and the spare parts operations could only accept a small portion of the unused parts from the warehouse. Noah Lotte had just taken a supply chain course in his master’s program and he ‘knew a lot’ about the analytical tools that could be used to optimize safety stock for a part with delivery and demand data. Noah knew he had a golden opportunity at his hands – collect historic data on a handful of parts, calculate the averages and standard deviations of demand and delivery lead time and then plug those numbers into the safety stock equation from his text book. As a result he would provide LV with a statistically derived level of safety stock inventory that would protect production while saving the company potentially millions of dollars in waste.

Noah launched himself into this initiative and began learning about the data systems that captured the information he needed. Unfortunately, the company’s legacy production planning systems did not make historical data searches easy and he needed to rely on the support of a few key supply chain managers to access the data. Anne Teak was a key supply chain manager at LV that Noah needed to perform the required data download for his project. The work Anne needed to do for Noah was a bit tedious but only she could pull the data from the system and she wasn’t able to delegate the work. Given the roles and multiple responsibilities that Anne had as a manager, Noah’s request was unusual work for her to do and would take up at least a few hours of her time. Little did Noah know, but the management development program he was aspiring to be a part of was resented by many in the company and all knew that Noah was a possible candidate for the program. Anne Teak was one of those employees that had worked decades at the company to rise to the level of manager and was not appreciative of the young new MBA hires that could come in and achieve her level of responsibility in a few short years. Noah was not aware of this background and when Anne was not responsive to his requests for the data pull, he began following up on a daily basis to push the initiative through. After a few days of persistent follow up, Anne gave Noah an insincere smile and stated dryly, “I think you are getting a bit too big for your britches! I’ll do it when I have time”. Noah was a taken aback and shocked at the resistance he was getting for trying to do the right thing for the company.

Eventually, with the support of Noah’s manager, who sought support of his boss (the director of international logistics), who then sought the support of Anne’s director, who then talked to Anne, the data was eventually retrieved and provided to Noah. What could have taken 24 hours, however, instead took many weeks to achieve. After gathering the data, Noah calculated the needed safety stock levels as planned for multiple parts and presented his findings to the executive director of supply chain management and his leadership team. The analysis was well received and approved for implementation, and would go on to be the standard process for managing safety stock for the company’s inbound international parts. At the end of the summer, Noah received the full time job offer into the management development program he so desired. Despite Noah’s success, he felt he had missed the mark in his dealings with Anne Teak and had already developed an uncooperative relationship that he feared could come back to haunt him.

Case study debrief

Both hard skills and soft skills were at play in this case. Here are some questions for thought and discussion:

- What is your assessment of Noah’s hard vs. soft skills?

- How would you rate Noah’s approach in getting Anne’s assistance?

- What could Noah have done differently?

- Was Anne’s behavior in stonewalling Noah’s efforts justified? Why or why not?

- How do you assess Noah’s actions in getting the issue resolved?

- What was the role of trust in this case and how was trust perceived by Noah and by Anne?

- Would your answers to the above questions be any different if Noah found out that Anne Teak was planning to retire in a few months and he wouldn’t have to deal with her again? Why or why not?

- What was the supply chain impact by the two-week delay in acquiring the data?

The complexity of supply chain design and execution

Supply chains are complex systems made up of business to business relationships, supply contracts within those relationships, and everyday operational actions where data, products, services and money flow between supply chain partners so that companies can achieve their business objectives and ultimately satisfy the end customer’s needs. Any single end product can have its supply chain traced upstream through the different tiers until one arrives at the tier where base raw materials are initially extracted from the earth. Supply chains are rarely designed in their entirety by any single company or person – in fact, rarely will any single company or person in the supply chain have full information regarding which companies and supply locations comprise the entire supply chain that they are a part of. While developing such an understanding and supply chain map is not impossible, the complexities and conflicting interests associated with doing so can limit full visibility of to any single player.

A supplier, for example, may not readily share its own supplier list with its customer in fear that the customer may go directly to those companies and attempt to disintermediate that supplier, or even just acquire cost data that may compromise its future negotiation power. Additionally, as long as a supplier is performing to expectations, then the customer may not see value in spending limited resources in finding out who supplies who in their supply chain. As a result, there may be hidden complexities, hidden risks and hidden events that never come to the attention of downstream companies and their buyers. Only when a major disruption happens that impacts multiple tiers in a supply chain do these downstream companies become interested in what is happening in the upstream tiers of their supply chain. The increasing frequency of global supply chain disruptions (natural disasters, political and economic), however, are pushing firms to get more and more involved with complete supply chain management; as they do so, supply chain professionals who can better manage communication, relationships, negotiations and create bridges of understanding and shared purpose become ever more critical to the firm.

There are two key phases to supply chain management: designing the supply chain and running the supply chain.

Designing the supply chain takes place before a product or service is launched to the customer and often takes place when that product or service is being developed. The design phase requires a company to both identify its customers and suppliers for the product and to determine how it will move those products and components along the supply chain. Modes of transportation and warehousing/inventory strategies must be identified and contracts with logistics services providers need to be procured. Ultimately, a firm needs a plan for every part it moves and needs a production strategy that complements its business strategy. In all this planning, the firm needs to ensure that its supply chain is designed to deliver the outcomes that match the customers’ desired outcomes. Some supply chains are designed to deliver a consistent level of acceptable quality with the lowest price possible, while other supply chains are designed to deliver the most innovative products, or have the fastest response, but with acceptably higher prices. These differing outcomes will result in differing supply chain design decisions. In addition to identifying the companies to be included in a supply chain, a firm must also define the processes that will be used to share data, generate a materials requirement plan and supplier shipping schedules and how money will be paid.

Designing the supply chain requires buyers in a supply chain organization to negotiate new contracts with suppliers. Sometimes the suppliers are companies that have previously supplied parts to the firm while other times they will be first time suppliers. In both cases, it is important that expectations and standards are clearly communicated and agreed upon. Buyers often focus on developing their negotiation skills given their pivotal role in establishing financial contracts of supply with suppliers and the impact that such contracts will have on the financial performance of the firm. When these negotiations span different countries, then buyers need to also have capabilities in international business and cross-cultural negotiations. Also, negotiations for buyers frequently take place internally to the firm as supply chain, marketing, engineering and finance each try to maximize their functions’ objectives and some times these objectives conflict. Engineering desires highly reliable materials and designs that sometimes drive costs beyond the allowable cost budget for the project. When this happens, finance can pull the reigns on spending; purchasing is then caught in the middle, attempting to either convince finance to loosen the purse strings a little or to convince engineering to modify their requirements in a way that saves money. Buyers often find themselves negotiating more internally within the firm than they do externally between firms to resolve such conflicts. Supply chains are complex and the soft skills needed to navigate the process of supply chain design are critical to the success of any supply chain professional involved in that process.

Once the supply chain has been carefully designed, it must then operate successfully. Running the supply chain is completely different than designing the supply chain. Running the supply chain requires ensuring that the processes that were initially designed are implemented according to plan. If all ran according to plan, then those responsible for running supply chains would have a pretty easy life. Despite the best well-laid plans, however, the real world has a tendency to throw curve-balls that were never anticipated. Such is the life of those running supply chains. Despite the ever increasing use of autonomous robots, machines and vehicles and the ever increasing use of analytics, artificial intelligence and complex supply chain management software, issues arise that such systems are not ready to deal with.

Despite the advancement of technology, there are no better machines designed to solve problems than human beings and the human brain/intellect. Humans continue to be the absolute most valuable resource in all global supply chains. Humans last on average seventy to eighty years and operate on a variety of organic material while requiring infrequent maintenance operations or tooling changes – they do require six to eight hours of downtime per day but are able to produce eight to twelve hours of value adding activity in any given day on a consistent basis. Once humans are developed and trained (often during their first twenty to thirty years of life), they can then provide problem solving skills and labor for forty years or more before they self select to stop providing such skills to the global economy and go into a reduced operational phase that most call retirement. Even humans that are paid minimal wages for repetitive labor in third-world countries can provide critical problem solving input regarding the tasks that are continuously set before them. Unlike machinery and equipment that require a large upfront fixed cost investment and minimal variable cost, hiring human problem solvers dedicated to a single firm requires minimum fixed costs but much larger variable costs in terms of wages and benefits.

The most successful supply chain managers are those that understand and leverage the human problem-solving capabilities both within their own firm and across firm boundaries. Soft skills are those skills that allow one to connect with and create bridges of understanding, cooperation and collaboration with other humans, other teams and other companies. While hard skills alone are a powerful value creation engine for a firm (think Noah Lotte’s knowledge of safety stock calculations), it is the soft skills that allows companies to access and leverage the hard skills of other humans. In the case vignette at the beginning of this chapter, the lack of soft skills by both Noah Lotte and Anne Teak held back the potential to create value for LV by a number of weeks. Soft skills are the mechanisms that release the full potential of the hard skills that reside with individuals up and down the supply chain.

While soft skills can help provide access to the potential of hard skills that reside in other humans, trust becomes the lubricant that can accelerate and speed up that access. More about trust is discussed at the end of this chapter – first we discuss in more detail the different levels of relationships in supply chain management and the soft skills needed to unlock the potential in each.

Relationship Building at Four Levels

Relationship building takes place at four levels: 1) individual, 2) team, 3) intra-firm (within a company but across departments) and 4) inter-firm (company to company). Without some level of competence on what drives successful individual relationships, it is difficult to be effective in effective team dynamics. Understanding what drives successful teams in turn can help one better manage both intra-firm and inter-firm relationships.

A. Individual Level

The Foundations of One-on-One Human Relationships: Lessons from Dale Carnegie

One of the most well known and enduring guides on interpersonal dynamics is Dale Carnegie’s How to Win Friends and Influence People. Though first published in 1936, its principles remain relevant today and continue to be the foundation of building effective relationships. While Dale Carnegie discusses thirty unique points in his book, we provide an overview of a few of his principles here. We highly recommend that any student of business make reading and studying Dale Carnegie’s book a priority. Additionally, we recommend taking each principle one at a time and and implementing that principle in a personal experiment for 24 to 48 hours to explore its potential in impacting personal relationships either at home, at school or in the work place. Here are a few of the principles along with quotes from his book:

1. Show Genuine Interest in Others

At the heart of human relationships is the simple act of caring. Carnegie emphasizes that being genuinely interested in others—beyond transactions or obligations—builds a strong relational foundation.

“You can make more friends in two months by becoming interested in other people than you can in two years by trying to get other people interested in you.”

In supply chain interactions, whether dealing with suppliers, customers, or team members, taking time to ask about a person’s background, interests, or challenges humanizes the relationship and helps build rapport. When others see that you are interested in them as human beings, they are more likely to trust your intentions.

2. Smile: The Universal Welcoming Signal

Nonverbal communication often speaks louder than words. Carnegie advocates the power of a simple, sincere smile.

“A smile says, ‘I like you. You make me happy. I am glad to see you.’”

In tense negotiations or simple interactions, a smile sets the tone for collaboration and approachability. A smile can communicate trust and that you have their best interests at heart.

3. Remember and Use People’s Names

Names carry personal identity. Carnegie notes that remembering and using someone’s name is a subtle but powerful way to honor their individuality.

“Remember that a person’s name is to that person the sweetest sound in any language.”

Supply chain professionals often interact with diverse stakeholders. Using names thoughtfully signal a sincere interest in the other person and can help engender trust. Write down names of people you meet and make sure you have learned the pronunciation of their names correctly. Review your notes and memorize names so that you can recall them when you meet again with that person.

4. Be a Good Listener

Active listening is not just about hearing words—it’s about making the other person feel heard and valued. Carnegie stresses the importance of listening more than talking.

“If you want to be a good conversationalist, be a good listener. To be interesting, be interested.”

Listening attentively to concerns—be it from a warehouse supervisor or a logistics partner—often uncovers critical insights and builds mutual respect.

5. Talk in Terms of the Other Person’s Interests

People are naturally drawn to topics that matter to them. Carnegie advises aligning conversations around the interests and goals of the other person.

“Talk to someone about themselves and they’ll listen for hours.”

In supplier meetings or stakeholder presentations, framing your message around the other party’s priorities increases receptiveness and collaboration and in turn opens the door for the other party to be interested in your own priorities and objectives.

6. Make the Other Person Feel Important—Sincerely

At the core of all human relationships is the desire to feel respected and appreciated. Carnegie urges us to acknowledge others’ contributions with sincerity.

“The deepest principle in human nature is the craving to be appreciated.”

Recognition doesn’t have to be grand—small acts like thanking a team member for meeting a tight deadline or acknowledging a vendor’s flexibility go a long way. One example of simple recognition that the author of this chapter experienced was when he was a parts buyer and purchased 400 Krispy Kreme Donuts and drove them three hours to a supplier’s production facility and gave them to all the hourly workers, thanking them for the consistent quality of parts they produce. Years later, the leadership of that supplier would still comment and express appreciation for that act of recognition of their hourly line workers.

B. Team Level

Building and managing effective teams is a topic of intense study and focus not only in business but also in other organizational settings such as non-profit and governmental groups. Companies and organizations invest much money on consulting and team building initiatives attempting to develop higher performing teams. The following are key principles highlighted in research and business publications regarding effective teams. At the end of this section are citations that the student can read for more in-depth information.

1. Effective teams are built on the foundation of psychological safety

Teams perform best when members feel safe to take risks, voice opinions, and admit mistakes without fear of embarrassment or punishment.

Harvard professor Amy Edmondson popularized this concept in her early research in the late 90’s. In his 2014 book Leaders Eat Last: Why Some Teams Pull Together and Others Don’t, author Simon Sinek argues that effective teams exist when leaders create a safe environment for team members where leaders prioritize team success and well-being above even that of their own. Sinek uses an example from the U.S. Marine Corps where leaders eat last and the most junior soldiers eat first, creating a symbol of servant leadership that permeates the team dynamics where team members trust and believe their leaders.

Supply chain teams that embrace a foundation of psychological safety will be those teams that do not delay delivery of bad news, are willing to share out-of-the-box thinking and ideas. These actions can lead to more responsive and innovative supply chains. Pyschological safety also becomes important in facilitating a learning mindset as opposed to a blaming mindset.

-

Source: “No one wants to look ignorant, incompetent, intrusive, or negative.” — Edmondson, 1999

2. Clear Goals and Roles Improve Performance

Clarity in a team’s purpose, and each member’s responsibilities, reduces conflict and enhances accountability. While some expectations of performance can be included in a contract, effective supply chain teams are careful to articulate agreements and expectations in less formal documentation such as emails, memorandum of understandings, presentations, and frequent live conversations and reviews of performance.

-

Source: Richard Hackman (Harvard) emphasized that well-structured teams have defined goals, roles, and norms.

3. Trust and Mutual Respect Are Core

High-performing teams are built on interpersonal trust—confidence that teammates will be reliable, competent, and have good intentions. Trust has two key components: first, trust in the competence of another person/group/company; second, trust in the intentions of the other person/group/company and that those intentions are to not harm. A supplier that trusts in the intentions of its buyer will be more likely to provide the type of transparency that helps buyers better understand the costs and risks associated with that supplier. A buyer that uses that information constructively will help build trust for future interactions.

-

Source: Patrick Lencioni (The Five Dysfunctions of a Team) identifies absence of trust as the root dysfunction in team failure.

4. Diversity Enhances Creativity (When Managed Well)

Teams with cognitive and demographic diversity generate more innovative solutions—but only when inclusive norms are in place. In a global supply chain, a buyer of a technical product may consider suppliers from different parts of the world in order to better leverage the engineering capabilities of different countries. Germany and Japan, for example are highly competent places to purchased car radios, however, the engineers from the two countries have different educational upbringings and provide different strengths that can be leveraged. A purchasing organization may decide to strategically split their radio business between two firms from two different countries in order to leverage the strengths from the two countries. At the team level, the same concept can enhance team dynamics as those from different backgrounds may approach problem solving uniquely in ways that help a team more quickly find solutions to problems. Managers and teams that embrace diversity with an environment of mutual respect for each others differences can expect to achieve higher levels of performance.

-

Source: Scott Page’s work on diversity and complex problem-solving; also supported by McKinsey’s inclusion-performance studies.

5. Healthy Conflict is Productive

Constructive debate (task conflict) leads to better decisions, while personal conflict (relationship conflict) is damaging. In a supply chain context, embracing healthy conflict is a key element of the corporate culture of a company and can extend to interfirm relationships. Provided the other foundational team concepts previously listed are in place (especially that of psychological safety), then a team can engage in healthy conflict where team members help challenge suggestions and plans in ways that allow the team to more fully analyze the pros and cons of strategies and courses of action being considered. Leadership is responsible for creating this type of culture in their organizations. Leaders should not feel threatened by peers and subordinates that challenge their ideas and should not see such challenges as personal attacks or attacks on their legitimacy as leaders. An effective leader will solicit all types of feedback and will then make the best decision with that feedback. Effective leaders provide transparency as to why certain decisions were made, even if the decision was not inline with other suggestions. When a leaders such as an executive director models this behavior with their direct reports (Directors), then those directors are more likely to mimic this style of leadership and openness with their direct reports (managers) and so forth.

-

Source: Jehn (1995) found that moderate task conflict improves performance, especially in non-routine tasks.

6. Communication Quality Trumps Frequency

Effective teams exhibit equal participation, high energy in exchanges, and rich face-to-face interactions. Effective buyers do not sit at their desk at all times, but are looking for opportunities to visit suppliers whether locally or globally. While business travel takes time and money, the richness and benefits of face-to-face communication and relationship building can outweigh such costs. As mentioned earlier, trust is a critical lubricant to supply chain relations and can allow companies in a supply chain to more quickly commit resources and investments to solving problems and creating new and better ways of doing things. Where trust does not exist, such investments will be questioned until assurance of protection is achieved; as a result issues may linger longer and the costs of supply chain disruptions can increase. Improving the quality of communication that is two-way, is inclusive of all involved and that engages openness with high energy exchanges and is face to face are important concepts to achieve high performing teams in the supply chain.

-

Source: MIT’s Human Dynamics Lab (Pentland, 2012) used sociometric data to track communication patterns in successful teams.

7. Strong Leadership Supports but Doesn’t Dominate

Team leaders set vision, remove obstacles, and cultivate team norms—but effective teams often share leadership functions. Sharing leadership functions can take on many forms. An executive director could ask a high performing entry level buyer to take on a special project of organizing a supplier conference for those suppliers under the executive director’s responsibility. This special project would achieve multiple objectives: first, it can provide the buyer a professional growth opportunity. Second, it allows the leadership team to see how the buyer responded to a challenge. Third, the special assignment can help signal that leadership is accessible and open to interacting with all levels of employees directly. Hierarchical isolation can be problematic in an organization where a certain leader discourages his direct reports from interacting with that leader’s boss. Such domination of one’s direct reports can reduce psychological safety of a team and lead to reticence and fear of sharing ideas.

An effective team leader understands their own limitation to understand and control all activities engaged in by team members. It requires a certain level of vulnerability for a leader to say to a team member, “I don’t have the information and knowledge that you have in your day to day tasks, so please tell me, how can I support you? What obstacles are you facing that I can help remove? If we can change something that we are doing, what would it be?” The common thread in these types of questions is that a leader is there to listen and support, rather than dominate the individual team members. In a supply chain context, this can be an important concept as a buying organization solicits feedback from its suppliers on these exact same questions, but in a business to business context…

How can I as a buying organization better support you, the supplier company?

What obstacles does your company face that the buying company can help remove?

Is there something that we are doing as a buying organization that you would like us to change? What would that be?

-

Source: Katzenbach & Smith (The Wisdom of Teams) and studies on shared leadership in agile and cross-functional teams.

Detailed Sources and Readings for improved Team management:

1. Amy Edmondson – Psychological Safety

-

Edmondson, A. (1999). Psychological safety and learning behavior in work teams. Administrative Science Quarterly, 44(2), 350–383.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2666999

2. J. Richard Hackman – Team Structure and Performance

-

Hackman, J. R. (2002). Leading Teams: Setting the Stage for Great Performances. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

3. Patrick Lencioni – Team Trust and Dysfunction

-

Lencioni, P. (2002). The Five Dysfunctions of a Team: A Leadership Fable. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

4. Scott Page – Diversity and Problem Solving

-

Page, S. E. (2007). The Difference: How the Power of Diversity Creates Better Groups, Firms, Schools, and Societies. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

5. Karen Jehn – Task vs. Relationship Conflict

-

Jehn, K. A. (1995). A multimethod examination of the benefits and detriments of intragroup conflict. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40(2), 256–282.

https://doi.org/10.2307/2393638

6. Alex Pentland – Communication Patterns and Team Performance

-

Pentland, A. (2012). The new science of building great teams. Harvard Business Review, 90(4), 60–69.

https://hbr.org/2012/04/the-new-science-of-building-great-teams

7. Katzenbach & Smith – Team Fundamentals and Leadership

-

Katzenbach, J. R., & Smith, D. K. (1993). The Wisdom of Teams: Creating the High-Performance Organization. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

C. Intra-Firm Level (across departments of the same company)

While specific functions in a company allow employees to be tasked with a specific outcome (eg. marketing, finance, engineering, etc.), such organizations can operate in a manner that optimizes their own objectives while at the expense of other objectives that may still be important to the overarching goals of the firm. Marketing, for example, is tasked with increasing revenue and that is what employees in the marketing function are held accountable to. In the meantime, engineering is tasked with ensuring designs are reliable and built according to specifications. Engineers are measured on the quality measures of the parts they are responsible for and also that new products launch on time. One of the major initiatives that helps improve quality of operations and launching on time is complexity reduction. High complexity is more difficult to manage and creates more opportunity for quality mistakes to take place. A potential conflict can arise if marketing is asking for multiple variations of a product (10 different colors for example) to satisfy a broad spectrum of customer tastes while engineering and the suppliers are asking to keep the variations to only one or two colors at the most. The supplier may have to spend much time and resources in changing over machinery to handle different color variations, so keeping such variations to a minimum helps the supplier keep costs down and also supports improved quality outcomes for engineering. Often, purchasing will be caught between these opposing objectives and will find themselves needing to help facilitate a negotiated resolution internally that satisfies the different functions.

The key strategy in resolving intra-firm conflict lies in elevating everyone’s view to that of the company as a whole and to creating value for the target customer being served.

What follows is a case vignette that illustrates how our protagonist from earlier in this chapter, Noah Lotte, was able to confront and manage intra-firm conflict at the company.

Case Study

Noah Lotte was enjoying his full time job at LV and was promoted after 18 months to be a global team leader over the switches and horns purchasing team, reporting directly to a highly regarded global commodity manager named Scott Maybach. Scott was an effective team builder and had come from an engineering background himself and was recently assigned to the switches and horns team that had been struggling with cost and quality issues previously. Noah and Scott reviewed the parts purchased and list of suppliers and began meeting with suppliers and LV engineers to better understand the landscape of the products being purchased and challenges that the team was facing. One consistent theme from both suppliers and engineering was that part number proliferation was becoming unmanageable and needed to be reigned in.

Noah looked into the data and realized that LV was releasing over a dozen color variants of the exact same window lift switch. If any engineering change was made to the switch, then over a dozen part numbers needed to be re-released and managed in the supply chain, simply because of the color variations. Meanwhile, a similar story was taking place with horns, where the company had over two dozen part numbers for horns across the globe.

Noah had recently taken a Dale Carnegie course on human relations and realized that he needed to effectively ‘dramatize your ideas’ to help both marketing/design and engineering understand and appreciate the complexity their decisions were driving into the supply chain. In order to create a shared vision across the different departments, Scott gave Noah the go ahead and support to set up a ‘war room’ where different functions could come together and visualize the complexity that existed. Noah found a conference room that wasn’t being used in an adjacent building and received permission to take it over full time. He cleaned up the room and then set up tables across the room where sample switches and horns from not only LV, but also from LV’s competitors were set up. Walking around the room gave a person comparative visibility to how complex each supply chain was for all major automotive manufacturers and how that complexity stacked up against that of LV’s supply chain. On one side of the room, a few tables were dedicated to just window lift switches. Each switch was tagged with a label giving its part number, supplier and color name. What was interesting was how little space the Japanese automotive manufacturers took on the table. The reason was that they only used one color: black. Additionally, Noah had purchased window lift switches from both Toyota and Lexus and demonstrated on the table that ALL of the Toyota brands, including Lexus, used the exact same window lift switch, irrespective of the interior color of the seats and dashboard. Then, one look at the LV table of window lift switches provided a completely different story. There were switches all over the LV table and some of them had what seemed to be different colors but had a very slight difference in hue – for example, a ‘desert sand’ color and a ‘cashmere’ color used the same mechanical switch but were a light beige color that differed only upon extreme close examination but yet had different part numbers. Suppliers complained that managing such complexity in their own assembly plants and supply chains drove significant costs into their processes that they then had to incorporate into the pricing they charged for their products.

The horns table showed a similar story. Different horns were being used across the globe whereas competitors had simplified their horn portfolios to a high tone and a low tone horn (and a disc horn in high humidity markets). LV’s largest horn supplier, Vincenzo Horns, made a significant proposal- grow them to be the sole supplier of LV’s global horn business over a three-year timeframe and they would help LV reduce the price of horns 30% during those three years. The different program teams for LV were not initially convinced with the need to commonize horns, so Noah decided to ‘dramatize his ideas’ in a different way. With the help and support of engineering, they retrofitted a number of LV’s different vehicles with different horns and invited representatives from the different program teams to meet at a certain day/time to discuss the commonization strategy. When they arrived for the meeting, Noah took them to the parking area where the vehicles were prepared and explained that they would have a horn “honk-off” and see if each person could correctly identify their horn from their program. Through this dramatization and a bit of humor, most (not all) of the leaders saw the light and realized that commonizing horns could be a good strategic move for LV and that maintaining slightly different sounding horns was not a key value proposition for the company. The only exception was LV’s luxury brand team that immediately identified their horn sound on another vehicle and insisted that their horn had to sound different from that of other LV vehicles.

Ultimately, the horn commonization strategy with the exception of the one luxury brand was approved and implemented globally for significant savings while commonizing all switches to a black color was not approved. The marketing/design team did, however, agree to be aware of and reduce as much as possible the color palette proliferation so that the company would not have two beige colors that could only be differentiated by professionally discerning eyes. Scott and Noah and their global team were recognized for their creative approach to achieving the savings generated, not just for the cost impact itself, but also for the supply chain complexity reduction and improved understanding across functions that their initiatives created.

It took much effort, planning and personal contact and communication with the differing functions to set up the stage where all could finally see with one vision the impact of supply chain complexity on the company. This case vignette highlights how soft skills were instrumental to communicate and negotiate with the differing functions in a company. Here are some questions for consideration and discussion.

- What is your assessment of Noah’s hard vs. soft skills?

- What did Noah do that was different in this second case study versus the first case study earlier in this chapter?

- What else could Noah have done to better bridge the understanding between engineering and marketing/design?

- How do you describe Noah’s boss, Scott Maybach?

- Was Scott an effective manager? Why or why not?

Intra-firm Level Conclusion

When functions in a firm become silos focused only on their key functional objectives, they can become a major supply chain bottleneck. Achieving internal stakeholder buy-in does not happen automatically but rather requires consistent concerted efforts on the part of supply chain management. Buyers, for example, would be well served to spend some time working near engineering and replace certain email traffic with face-to-face discussions. This can be facilitated with both buyers and engineering are co-located but not necessarily required. A buyer would also benefit by developing personal trusting relationships with the marketing side of the business to better understand the challenges, opportunities and emerging trends with the company’s key customers. Developing trusting relationships with employees of different functions can facilitate problem solving down the road.

Another interface that has not yet been mentioned is that of supply chain with finance/accounting. The contract changes that purchasing is able to achieve with price reductions (or increase) need to be tracked by finance/accounting. Most firms will generate weekly reports based on contract changes and the accuracy of these reports often requires detailed analysis by both functions. Additionally, sourcing new products requires the process of managing an allowable cost at the part-level. If purchasing has been given a specific allowable cost that they are having a hard time achieving, then timely communication with finance/accounting will help the program level personnel make important decisions as they oversee the business case for the entire product being developed. In short, supply chain has many internal interfaces within the firm itself that are important to manage. While hard skills are no doubt important for success, it is soft skills that differentiate successful supply chain employees, especially when it comes to intra-firm relationships.

D. Inter-Firm Level (Business-to-Business Relationships)

Since supply chain management is concerned with orchestrating the inflow of goods and services from suppliers and the outflow of finished products and services to customers, those working in supply chain management frequently find themselves working with employees from other companies. Some would argue that these relationship are much different from intra-firm relationships since each company wants to maximize their own profits and often paying a supplier more money is a direct transfer of profits from one company to another. If viewed in this way, it is easy to see how buyer/supplier relationships can become strained. The reality, however, is different when viewed from a long-term supply chain perspective. Both supplier and the buyer company are in a business relationship within a wider supply chain that has at its end a customer who can either purchase the product they are supplying or purchase another competing product from another competitor’s supply chain. The competition that is of most importance is the competition between supply chains, not between buyer/supplier pairs in a single supply chain. Just as Noah Lotte needed to appeal to the nobler motive of the intra-firm functions within a firm, so must supply chain employees appeal to the nobler motive of supply chain success as opposed to individual company success. In this manner, the strategies in managing inter-firm relationships are similar to the strategies for managing intra-firm relationships.

Strategic supplier/customer relationships require long-term trust, transparency, and communication. For those companies that source products and services globally, the added dimension of international differences can complicate relationship management. It is critical that such international relationships embrace cultural sensitivity, negotiation flexibility and expectations management using thorough communication processes. Cultural sensitivity requires individuals to study the history and norms of the country or region they are doing business with. The ultimate goal in any relationship is to develop the trust and understanding necessary to facilitate effective problem solving and decision making. When one understands the history of a country/region and the cultural norms of that people, they will better understand why those from that country/region act they way they do and what motivates their behavior and decision making. In the absence of such understanding, one may misinterpret situations and assume malicious intent when it does not really exist. Additionally, when one party makes strides to understand and appreciate the culture of the other party, then this creates a signal of trust that is more easily reciprocated. Negotiation styles differ across cultures and understanding these dynamics are important for any buyer to understand. Finally, expectations management required extra effort when working across cultures since verbal and non-verbal communication is not identical across cultures.

While international business-to-business relationships can be complex, they also can be rewarding in the form of better access to diverse technological solutions and also better understanding of local markets that a buyer company may want to enter from a sales standpoint. Relationships within a firm’s own country can also be challenging and require the same level of attention. Companies have their own business culture and communication styles and those engaging in such relationships should not take for granted assumptions of communication and expectations but rather should engage in efforts to engage in deep and meaningful communciation as outlined earlier in this chapter. Ultimately, business partners in a supply chain will need to come together to solve problems, resolve conflict, and create new solutions. Those employees with the soft skills needed to do so will create value for their companies and for their own careers.

Trust and its Role in SCM

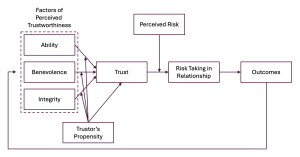

A stakeholder trust model is a framework for understanding and managing relationships with various stakeholders, recognizing that trust is a crucial element in these relationships. It acknowledges that organizations can benefit from fostering trust with their stakeholders, which can lead to stronger relationships, increased engagement, and ultimately, better outcomes.

Here’s a more detailed look at the model:

1. Identifying Stakeholders:

- A stakeholder is any individual or group that has an interest in or can be affected by an organization.

- This includes internal stakeholders like employees and shareholders, as well as external stakeholders like customers, suppliers, and regulators.

2. Understanding Trust:

- Trust is the belief in the integrity, character, and ability of an individual or organization.

- In the context of stakeholder relationships, trust is the belief that an organization will act in a way that is beneficial to its stakeholders.

3. Building Trust:

- Organizations can build trust with their stakeholders by demonstrating competence, integrity, and benevolence.

- This can be achieved through consistent communication, transparent practices, and fulfilling commitments.

- Radical transparency and consistency are key to building trust.

4. Benefits of Strong Stakeholder Trust:

-

Improved Relationships:

Trust leads to stronger and more collaborative relationships with stakeholders.

-

Increased Engagement:

Stakeholders are more likely to engage with an organization they trust.

-

Enhanced Reputation:

A reputation for trustworthiness can attract talent, investors, and customers.

-

Mitigation of Risk:

Strong stakeholder trust can help to mitigate potential risks, such as regulatory concerns or reputational damage.

5. Models for Understanding and Managing Stakeholder Trust:

Media Attributions

- Stakeholder Trust Model © Mayer, R. C., Davis, J. H., & Schoorman, F. D.