The Cattle Kingdom

Cattle, Cowboys, and Beef Barons

While the cattle industry lacked the romance of the Gold Rush, the role it played in western expansion should not be underestimated. For centuries, wild cattle roamed the Spanish borderlands. At the end of the Civil War, as many as five million longhorn steers could be found along the Texas frontier, yet few settlers had capitalized on the opportunity to claim them, due to the difficulty of transporting them to eastern markets. The completion of the first transcontinental railroad and subsequent railroad lines changed the game dramatically. Cattle ranchers and eastern businessmen realized that it was profitable to round up the wild steers and transport them by rail to be sold in the East for as much as thirty to fifty dollars per head. These ranchers and businessmen began the rampant speculation in the cattle industry that made, and lost, many fortunes.

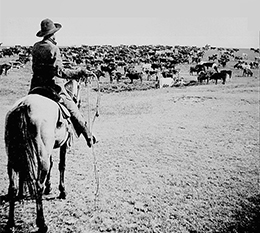

So began the impressive cattle drives of the 1860s and 1870s. The famous Chisholm Trail provided a quick path from Texas to railroad terminals in Abilene, Wichita, and Dodge City, Kansas, where cowboys would receive their pay. These “cowtowns,” as they became known, quickly grew to accommodate the needs of cowboys and the cattle industry. Cattlemen like Joseph G. McCoy, born in Illinois, quickly realized that the railroad offered a perfect way to get highly sought beef from Texas to the East. McCoy chose Abilene as a locale that would offer cowboys a convenient place to drive the cattle, and went about building stockyards, hotels, banks, and more to support the business. He promoted his services and encouraged cowboys to bring their cattle through Abilene for good money; soon, the city had grown into a bustling western city, complete with ways for the cowboys to spend their hard-earned pay (Figure 17.10).

Between 1865 and 1885, as many as forty thousand cowboys roamed the Great Plains, hoping to work for local ranchers. They were all men, typically in their twenties, and close to one-third of them were Hispanic or African American. It is worth noting that the stereotype of the American cowboy—and indeed the cowboys themselves—borrowed much from the Mexicans who had long ago settled those lands. The saddles, lassos, chaps, and lariats that define cowboy culture all arose from the Mexican ranchers who had used them to great effect before the cowboys arrived.

Life as a cowboy was dirty and decidedly unglamorous. The terrain was difficult, but the longhorn cattle were hardy stock, and could survive and thrive while grazing along the long trail, so cowboys braved the trip for the promise of steady employment and satisfying wages. Eventually, however, the era of the free range ended. Ranchers developed the land, limiting grazing opportunities along the trail, and in 1873, the new technology of barbed wire allowed ranchers to fence off their lands and cattle claims. With the end of the free range, the cattle industry, like the mining industry before it, grew increasingly dominated by eastern businessmen. Capital investors from the East expanded rail lines and invested in ranches, ending the reign of the cattle drives.

Americana

Barbed Wire and a Way of Life Gone

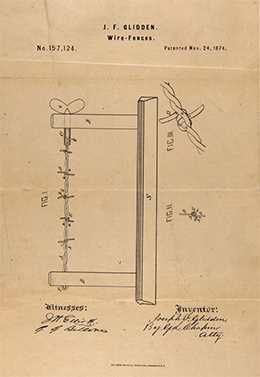

Called the “devil’s rope” by Native Americans, barbed wire had a profound impact on the American West. Before its invention, settlers and ranchers alike were stymied by a lack of building materials to fence off land. Communal grazing and long cattle drives were the norm. But with the invention of barbed wire, large cattle ranchers and their investors were able to cheaply and easily parcel off the land they wanted—whether or not it was legally theirs to contain. As with many other inventions, several people “invented” barbed wire around the same time. In 1873, it was Joseph Glidden, however, who claimed the winning design and patented it. Not only did it spell the end of the free range for settlers and cowboys, it kept more land away from Native tribes(Figure 17.11).

In the early twentieth century, songwriter Cole Porter would take a poem by a Montana poet named Bob Fletcher and convert it into a cowboy song called, “Don’t Fence Me In.” As the lyrics below show, the song gave voice to the feeling that, as the fences multiplied, the ethos of the West was forever changed:

Oh, give me land, lots of land, under starry skies above

Don’t fence me in

Let me ride thru the wide-open country that I love

Don’t fence me in . . .

Just turn me loose

Let me straddle my old saddle underneath the western skies

On my cayuse

Let me wander over yonder till I see the mountains rise

I want to ride to the ridge where the west commences

Gaze at the moon until I lose my senses

I can’t look at hobbles and I can’t stand fences

Don’t fence me in.