Federal Government Assistance

To assist the settlers in their move westward and transform the migration from a trickle into a steady flow, Congress passed two significant pieces of legislation in 1862: the Homestead Act and the Pacific Railway Act. Born largely out of President Abraham Lincoln’s growing concern that a potential Union defeat in the early stages of the Civil War might result in the expansion of slavery westward, Lincoln hoped that such laws would encourage the expansion of a “free soil” mentality across the West.

The Homestead Act allowed any head of household, or individual over the age of twenty-one—including unmarried women—to receive a parcel of 160 acres for only a nominal filing fee. All that recipients were required to do in exchange was to “improve the land” within a period of five years of taking possession. The standards for improvement were minimal: Owners could clear a few acres, build small houses or barns, or maintain livestock. Under this act, the government transferred over 270 million acres of public domain land to private citizens.

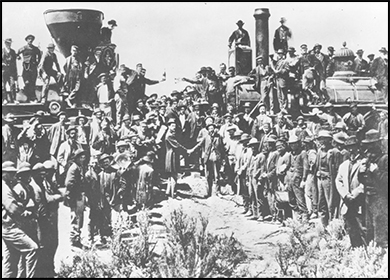

The Pacific Railway Act was pivotal in helping settlers move west more quickly, as well as move their farm products, and later cattle and mining deposits, back east. The first of many railway initiatives, this act commissioned the Union Pacific Railroad to build new track west from Omaha, Nebraska, while the Central Pacific Railroad moved east from Sacramento, California. The law provided each company with ownership of all public lands within two hundred feet on either side of the track laid, as well as additional land grants and payment through load bonds, prorated on the difficulty of the terrain it crossed. Because of these provisions, both companies made a significant profit, whether they were crossing hundreds of miles of open plains, or working their way through the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. As a result, the nation’s first transcontinental railroad was completed when the two companies connected their tracks at Promontory, Utah, in the spring of 1869. Other tracks, including lines radiating from this original one, subsequently created a network that linked all corners of the nation (Figure 17.4).

In addition to legislation designed to facilitate western settlement, the U.S. government assumed an active role on the ground, building numerous forts throughout the West to aid settlers during their migration. Forts such as Fort Laramie in Wyoming (built in 1834) and Fort Apache in Arizona (1870) aimed to facilitate trade and limit conflict between migrants and local American Indian tribes. Others located throughout Colorado and Wyoming became important trading posts for miners and fur trappers. Those built in Kansas, Nebraska, and the Dakotas served primarily to provide relief for farmers during times of drought or related hardships. Forts constructed along the California coastline provided protection in the wake of the Mexican-American War as well as during the American Civil War. These locations subsequently serviced the U.S. Navy and provided important support for growing Pacific trade routes. Whether as army posts constructed to aid American migration, or as trading posts to further facilitate the development of the region, such forts proved to be vital contributions to westward migration.