Chinese Immigrants in the American West

The initial arrival of Chinese immigrants to the United States began as a slow trickle in the 1820s, with barely 650 living in the U.S. by the end of 1849. However, as gold rush fever swept the country, Chinese immigrants, too, were attracted to the notion of quick fortunes. By 1852, over 25,000 Chinese immigrants had arrived, and by 1880, over 300,000 Chinese lived in the United States, most in California. While they had dreams of finding gold, many instead found employment building the first transcontinental railroad (Figure 17.15). Some even traveled as far east as the former cotton plantations of the Old South, which they helped to farm after the Civil War. Several thousand of these immigrants booked their passage to the United States using a “credit-ticket,” in which their passage was paid in advance by American businessmen to whom the immigrants were then indebted for a period of work. Most arrivals were men: Few wives or children ever traveled to the United States. As late as 1890, less than 5 percent of the Chinese population in the U.S. was female. Regardless of gender, few Chinese immigrants intended to stay permanently in the United States, although many were reluctantly forced to do so, as they lacked the financial resources to return home.

Prohibited by law since 1790 from obtaining U.S. citizenship through naturalization, Chinese immigrants faced harsh discrimination and violence from American settlers in the West. Despite hardships like the special tax that Chinese miners had to pay to take part in the Gold Rush, or their subsequent forced relocation into Chinese districts, these immigrants continued to arrive in the United States seeking a better life for the families they left behind. Only when the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 forbade further immigration from China for a ten-year period did the flow stop.

The Chinese community banded together in an effort to create social and cultural centers in cities such as San Francisco. In a haphazard fashion, they sought to provide services ranging from social aid to education, places of worship, health facilities, and more to their fellow Chinese immigrants. As Chinese workers began competing with White Americans for jobs in California cities, the latter began a system of built-in discrimination. In the 1870s, White Americans formed “anti-coolie clubs” (“coolie” being a racial slur directed towards people of any Asian descent), through which they organized boycotts of Chinese-produced products and lobbied for anti-Chinese laws. Some protests turned violent, as in 1885 in Rock Springs, Wyoming, where tensions between White and Chinese immigrant miners erupted in a riot, resulting in over two dozen Chinese immigrants being murdered and many more injured.

Slowly, racism and discrimination became law. The new California constitution of 1879 denied naturalized Chinese citizens the right to vote or hold state employment. Additionally, in 1882, the U.S. Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which forbade further Chinese immigration into the United States for ten years. The ban was later extended on multiple occasions until its repeal in 1943. Eventually, some Chinese immigrants returned to China. Those who remained were stuck in the lowest-paying, most menial jobs. Several found assistance through the creation of benevolent associations designed to both support Chinese communities and defend them against political and legal discrimination; however, the history of Chinese immigrants to the United States remained largely one of deprivation and hardship well into the twentieth century.

Defining American

The Backs that Built the Railroad

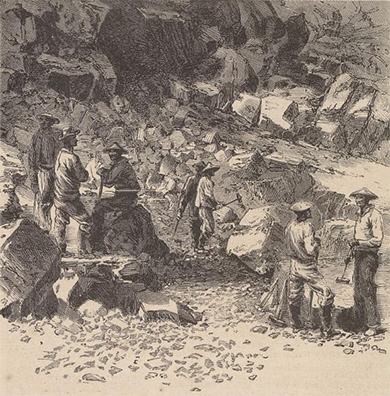

Below is a description of the construction of the railroad in 1867. Note the way it describes the scene, the laborers, and the effort.

—Albert D. Richardson, Beyond the Mississippi

The cars now (1867) run nearly to the summit of the Sierras. . . . four thousand laborers were at work—one-tenth Irish, the rest Chinese. They were a great army laying siege to Nature in her strongest citadel. The rugged mountains looked like stupendous ant-hills. They swarmed with Celestials, shoveling, wheeling, carting, drilling and blasting rocks and earth, while their dull, moony eyes stared out from under immense basket-hats, like umbrellas. At several dining camps we saw hundreds sitting on the ground, eating soft boiled rice with chopsticks as fast as terrestrials could with soup-ladles. Irish laborers received thirty dollars per month (gold) and board; Chinese, thirty-one dollars, boarding themselves. After a little experience the latter were quite as efficient and far less troublesome.

Several great American advancements of the nineteenth century were built with the hands of many other nations. It is interesting to ponder how much these immigrant communities felt they were building their own fortunes and futures, versus the fortunes of others. Is it likely that the Chinese laborers, many of whom died due to the harsh conditions, considered themselves part of “a great army”? Certainly, this account reveals the unwitting racism of the day, where workers were grouped together by their ethnicity, and each ethnic group was labeled monolithically as “good workers” or “troublesome,” with no regard for individual differences among the hundreds of Chinese or Irish workers.