College of Education

7 A Climate of Hope: Investigating Learning at an Innovative Museum Exhibit

Hailey Sherman; Lynne Zummo; Benjamin Janney; and Monika Lohani

Faculty Mentor: Lynne Zummo (Educational Psychology, University of Utah)

Museums are uniquely poised to engage in climate education efforts (e.g., Dillon et al., 2016). While many museums have implemented climate-focused exhibits in creative ways (e.g., Newell, 2020), empirical research on learning within such exhibits remains nascent (Zummo et al., 2022; 2024). This study aims to advance the field by analyzing learners’ experience in an innovative exhibit about climate change. Intentionally developed through rigorous prototyping and engagement with research literature on framing (e.g., Lakoff, 2010), A Climate of Hope (ACOH) uses strategic frames of “hope”, “local”, “community”, “better future”, and “playful” to engage learners with diverse views on climate change. For this study, we were specifically interested in relationships among visitors’ memory, learning, and incoming views of climate change. We drew on theories of social cognition (Frith & Frith, 2003; Meyer and Lieberman, 2012) to understand relationships among visitors’ memory, learning, and incoming climate views.

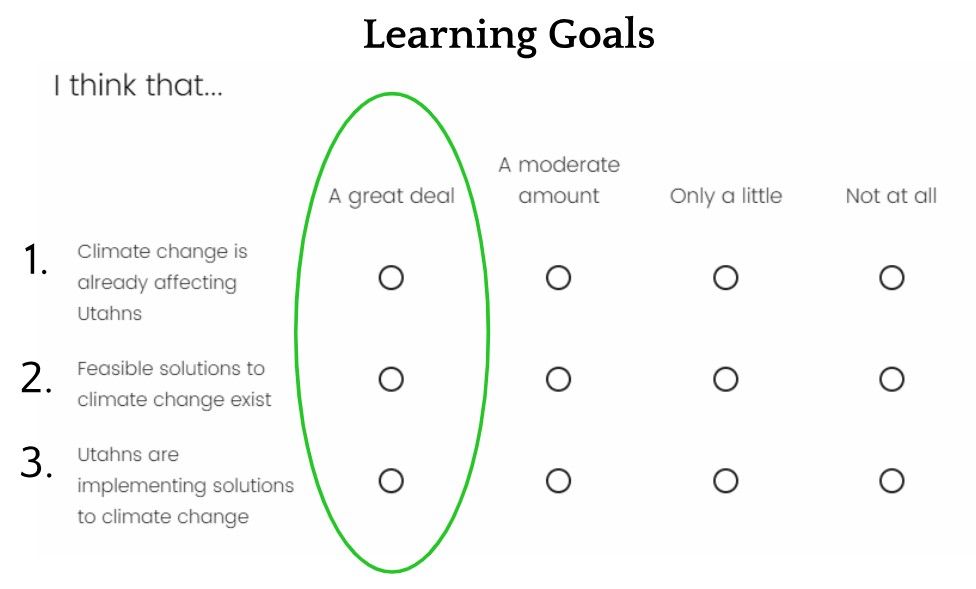

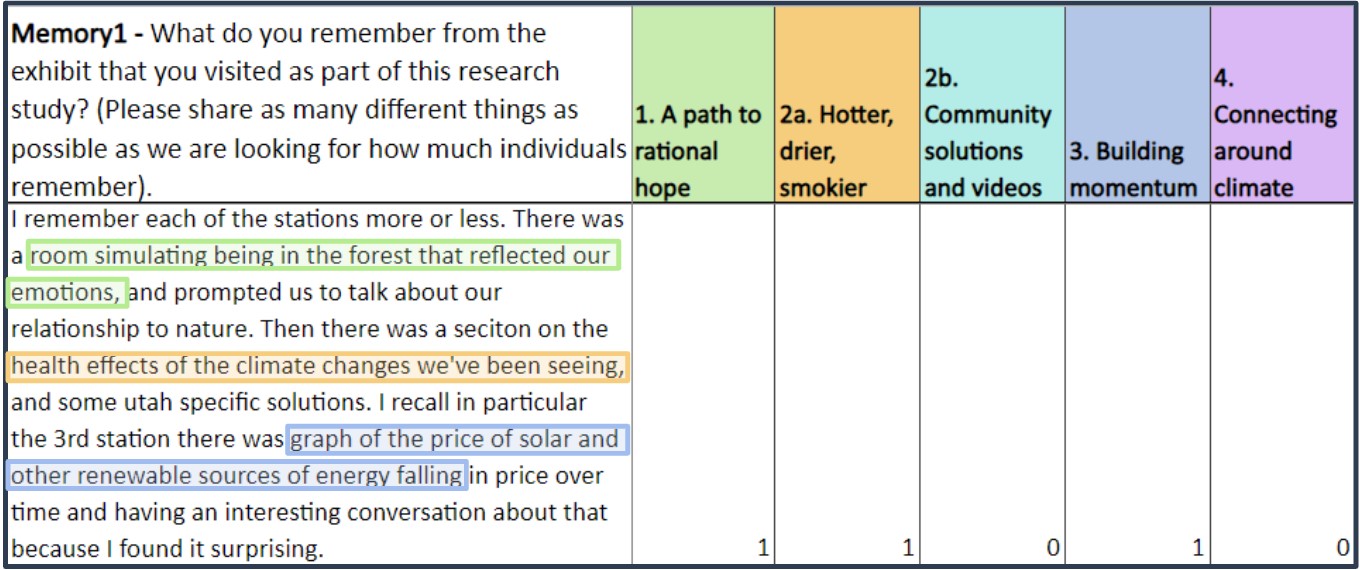

This mixed-methods study analyzed survey data collected before and 4-6 weeks following visitors’ engagement with ACOH. Survey items included demographics, views on climate change (as assessed through the Six Americas Super Short Survey [SASSY; Chryst et al., 2018]), measures intended to assess participants’ uptake of learning goals, and open-ended text responses eliciting participants’ memory of the exhibit. Questions used to assess learning goals are shown in figure 1. We developed a deductive coding scheme based on the content of ACOH to code open-ended responses, shown in figure 2. Then we used quantitative analysis to assess relationships among areas coded and survey measures using Fisher’s Exact Test, ordinal logistic regression, and the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test.

Figure 1. Questions asked 4-6 weeks after viewing A Climate of Hope to assess attainment of learning goals. Choices closer to “A great deal” represent greater alignment with the goals.

Figure 2. Deductive coding scheme developed to code open-ended memory questions based on which areas of A Climate of Hope participants recall. Coding as “1” means there is evidence of memory of the given section (as highlighted in this response)

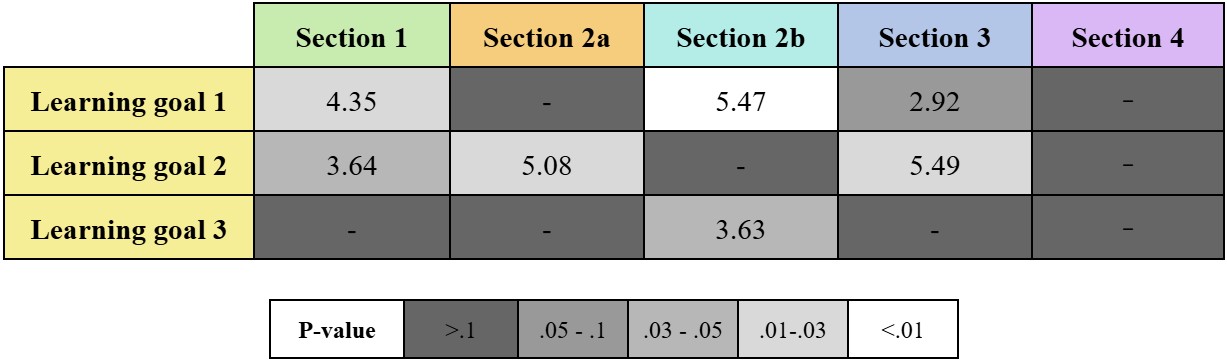

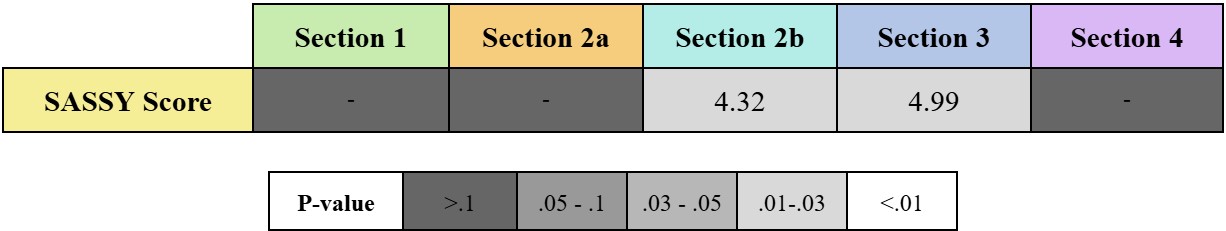

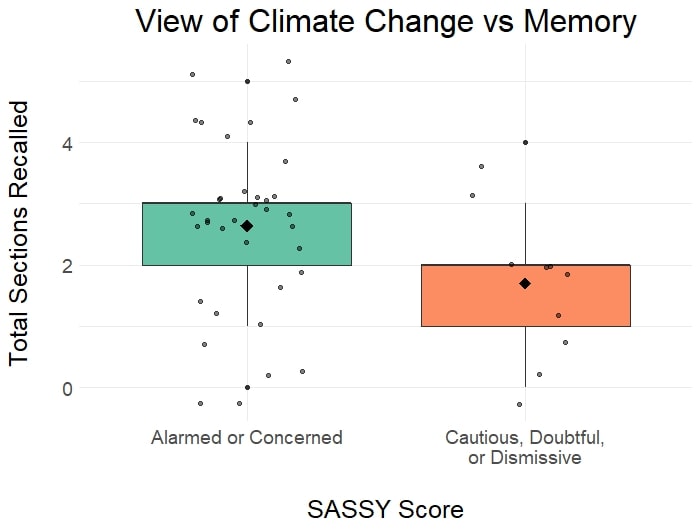

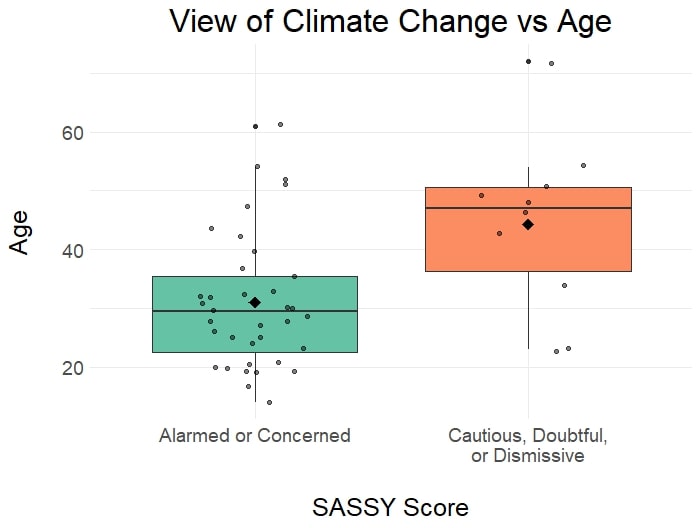

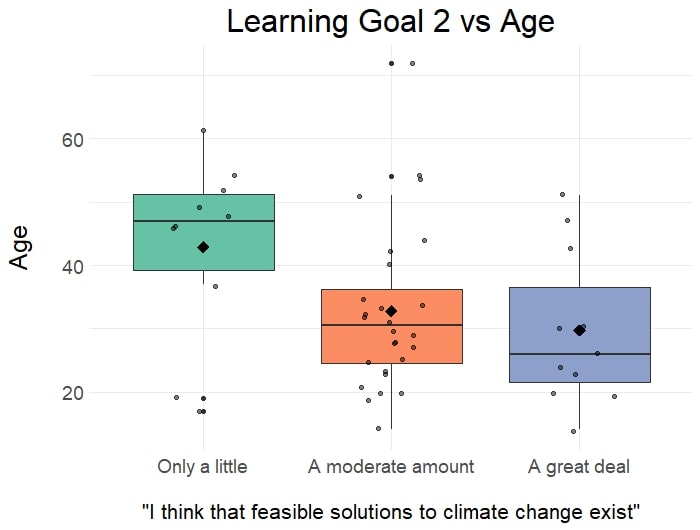

We identified several statistically significant relationships between participants’ memory of specific parts of the exhibit and likelihood of alignment with learning goals, shown in figure 3. For example, participants’ memory of a section of ACOH highlighting local climate impacts was associated with higher levels of agreement with the statement Climate change is already affecting Utahns (OR = 5.47; p=.006). Similarly, participants’ memory of a section focused on local, community-scale solutions increased the likelihood of greater agreement with the statement Feasible solutions to climate change exist (OR = 5.49; p=.01). We also identified relationships between visitors’ incoming views of climate change and their memory, with those who were “alarmed” or “concerned” having a higher number of total items recalled (p=.04; see figure 5), and being more likely than less concerned visitors to remember sections of the exhibit focused on solutions (p=0.01; see figure 4). It was also found that younger individuals were more likely to score as “alarmed” or “concerned” about climate change (OR = 1.06; p=.01; see figure 6) and more likely to agree to a greater extent that Feasible solutions to climate change exist (OR = 1.05; p=.028; see figure 7), although older individuals had greater increases in self-reported climate engagement after viewing the exhibit (OR = 1.07; p=.01; see figure 8).

Figure 3. Association between responses to learning goal questions and exhibit sections recalled in open-ended memory question 1, assessed using ordinal logistic regression. Odds ratios are listed showing the increase in likelihood that participants’ answers were more aligned with the learning goals (closer to “A great deal” than “Not at all”) given they reported remembering that section of the exhibit.

Figure 4. Association between participants scores on the Six Americas Super Short Survey (SASSY) and exhibit sections recalled, assessed using ordinal logistic regression. Odds ratios show the increase in likelihood that participants reported remembering the section of the exhibit, given they scored as more “alarmed” or “concerned”about climate change as compared to “cautious”, “doubtful”, or “dismissive”.

Figure 5. Relationship between participants’ SASSY scores and total number of sections recalled, assessed with the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test (p=.04).

|

|

Figure 6. (Left) When assessed with the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test, individuals scoring as “alarmed” or “concerned” were significantly younger (p=.04), with a median age of 29.5, compared to those who scored as “cautious”, “doubtful”, or “dismissing”, with a median age of 47. Figure 7. (Right) Significant relationship found between responses to learning goal question 2 and age using ordinal logistic regression (OR = 1.05; p=.028).

Figure 8. Both before entering the exhibit, and 4-6 weeks after, participants were asked “how often do you engage with or think about climate change during daily life?”. Using ordinal logistic regression, older individuals were found to be significantly more likely than younger individuals to list higher frequencies in the post survey than they did before entering the exhibit (OR=1.07; p=.01).

As a preliminary control due to low response rates, Fisher’s Exact Test and the Wilcoxon Rank Sum Test were run to assess overall differences between participants who did and did not respond to the delayed post survey. No significant associations were found, indicating that age, gender, SASSY score, and self-reported knowledge, frequency of conversations, and engagement around climate change are likely not major confounding variables.

This study demonstrates a potential connection between memory and learning within ACOH. Areas of the exhibit framed around “community”, “hope”, and “better future” appear especially linked to visitors’ understanding of learning goals, whereas the “playful” frame used in section 4 may be less influential. Solution information may also be more impactful for those most worried about climate change. Younger individuals’ greater levels of alarm about climate change and belief in solutions is insightful for museums creating exhibits tailored towards younger audiences. Greater increases in self-reported engagement in older individuals may be a sign that climate change museum exhibits are more effective at influencing older people than younger people (who may already be informed and concerned). Since self-reports of engagement can be inaccurate, better ways of measuring actual change in eco-friendly behaviors are needed. Additionally, this study was purely correlational, so causality cannot be determined. Further work is needed to determine factors contributing to learning and climate action.

REference

Chryst, B., Marlon, J., van der Linden, S., Leiserowitz, A., Maibach, E., & Roser-Renouf, C. (2018). Global Warming’s “Six Americas Short Survey”: Audience Segmentation of Climate Change Views Using a Four Question Instrument. Environmental Communication, 12(8), 1109–1122. https://doi.org/10.1080/17524032.2018.1508047

Dillon, J., DeWitt, J., Pegram, E., Irwin, B., Crowley, K., Haydon, R., King. H., Knutson, K., Veall, D. and Xanthoudaki, M. (2016). A Learning Research Agenda for Natural History Institutions. London: Natural History Museum.

Frith, U., & Frith, C. D. (2003). Development and neurophysiology of mentalizing. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358(1431), 459-473.

Lakoff, G. (2010). Why it Matters How We Frame the Environment. Environmental Communication, 4(1), 70-81. DOI: 10.1080/17524030903529749

Meyer, M. L., & Lieberman, M. D. (2012). Social working memory: neurocognitive networks and directions for future research. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, 571.

Newell, J. (2020). Climate museums: Powering action. Museum Management and Curatorship, 35(6), 599–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/09647775.2020.1842236

Zummo, L.M. & Massey, E. (2022). Using Synthetic Knowledge and Interaction Analysis to Investigate Learning in a Collaborative Digital Climate Learning Experience. In C. Chinn, E. Tan, C. Chan, & Y. Kali (Eds.) International Collaboration toward Educational Innovation for All: Overarching Research, Development, and Practices. ICLS Proceedings. 16th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS) 2022 (pp. 393-400).

Zummo, L.M., Menlove, B., & Massey, E. (2024). Navigating failure in a museum-based videogame: Convergent and divergent mechanisms of collaboration as potential levers for informal learning about climate change. Journal of Science Education & Technology.

Media Attributions

- 146881870_learninggoals

- 146882801_qualitiativecodingscreenshot

- Figure3

- Figure4

- 137489262_sassyvsmemory

- 146879582_sassyvsage

- 146879585_lg2vsage

- EngagementvsAge