College of Education

6 Using Non-fiction Multimedia Stories to Support Science Vocabulary Learning in Head Start Preschoolers

Gwendolyn Douglas and Claire Son

Faculty Mentor: Claire Son (Educational Psychology, University of Utah)

Abstract

This study investigates how using nonfiction multimedia stories with various attention-grabbing elements influences preschool children’s story interest and science vocabulary learning. Multimedia was designed to address (1) an instructional agent, aiming to direct the child’s attention with gestures and verbal cues and (2) an interaction target, aiming to reinforcing attention to either a relevant or irrelevant component of the illustration to move to the next page. Previous research suggested that the use of an instructional agent and relevant interaction items improves children’s attention, and fosters their interest, learning, and comprehension. Prekindergarten children in four Head Start sites (N=87) were assigned to read two multimedia stories about birds in one of the three conditions: No Agent– Relevant Target, Agent- Relevant Target, Agent– Irrelevant Target. Posttest vocabulary was tested to compare conditions.

Introduction

Early literacy is crucial for academic success, encompassing various skills, such as vocabulary acquisition, letter and sound skills, and comprehension. Preschool years are vital for developing these skills, and among them, vocabulary competence has been demonstrated as a strong predictor of later academic performance.

To support the important vocabulary, researchers have explored the use of novel technologies, such as digital eBooks, literacy apps, and multimedia animations. Among them, multimedia stories offer a promising tool for enhancing vocabulary learning, especially when they incorporate interactive elements in the multimedia story, like instructional agents and interaction targets. Previous research with elementary students suggests that instructional agents guide children’s attention through gestures and verbal cues, while interaction targets engage them with story illustrations, potentially making the learning experience more engaging and more effective.

To support the important vocabulary, researchers have explored the use of novel technologies, such as digital eBooks, literacy apps, and multimedia animations. Among them, multimedia stories offer a promising tool for enhancing vocabulary learning, especially when they incorporate interactive elements in the multimedia story, like instructional agents and interaction targets. Previous research with elementary students suggests that instructional agents guide children’s attention through gestures and verbal cues, while interaction targets engage them with story illustrations, potentially making the learning experience more engaging and more effective.

Method

Participants included 87 prekindergarten children (48 boys, 55.17%) from 15 classrooms across four Head Start sites in a mountain west region. The average age was 58.14 months (about 5 years). The sample was diverse with 44.83% dual language learners, including 37 Spanish speakers. Baseline skills were assessed using Picture Vocabulary and Science subtests from the Woodcock-Johnson IV Test for Oral Language and Achievement as well as interest surveys.

Multimedia nonfiction stories on bird beaks and bird feet were created using Photoshop and PowerPointShow. Each story had three versions: agent-relevant feature, no agent-relevant feature, and agent-irrelevant feature. Children were divided into high and low score groups based on pretest results and children in each group were randomly assigned to use a version of each story (i.e., stratified random assignment). They viewed the stories on an iPad and then answered questions assessing expressive and receptive vocabulary, and perceived interest. The impact of the multimedia stories was analyzed using ANOVA and multiple regression to compare the three conditions.

Results

Contrary to our hypothesis, the presence of a teaching agent and relevant interaction targets in multimedia stories did not significantly enhance vocabulary learning. ANOVA showed significant condition differences in beak receptive vocabulary, f(2, 93) = 2.49, p < .05, and feet receptive vocabulary, f(2, 87) = 4.058, p < .05, with the lowest scores for Agent-Relevant Target condition and the highest scores for No Agent-Irrelevant Target condition.

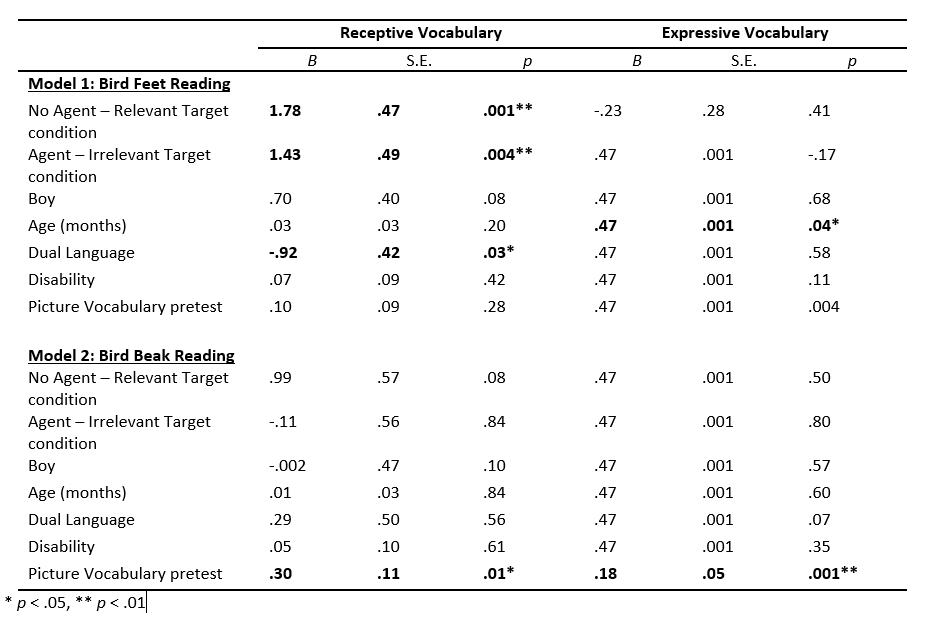

We ran multiple regression with two dummy variables indicating Agent-IrrelevantTarget and NoAgent-RelevantTarget, with Agent-RelevantTarget as a reference. Pre-test vocabulary and demographic information of age, gender, home language and disability status were controlled. Results showed that for bird beak reading, children in NoAgent-RelevantTarget condition scored higher receptive vocabulary than Agent-RelevantTarget (B=.990, p=.084, NS); the difference approached significance after controlling for covariates. For bird feet reading, children in NoAgent-RelevantTarget condition scored significantly higher receptive vocabulary than Agent-RelevantTarget (B=1.729, p<.001), and children in Agent-IrrelevantTarget scored significantly higher scores than Agent-RelevantTarget (B=1.432, p=.004).

Conclusions

This study found that neither teaching agents nor relevant interaction targets in multimedia stories significantly improved vocabulary learning in preschool children. Rather, having a teacher agent seems to overload children’s cognitive processing and lead to lower vocabulary scores. Further, an irrelevant but cute image may be more engaging than a relevant image to focus on. The results suggest that reducing cognitive load and utilizing more engaging elements, along with more rigorous or repeated vocabulary exposure, would be more effective for preschoolers’ vocabulary learning. Further research is needed to explore other interactional and engaging elements in multimedia stories to enhance early vocabulary learning.

Media Attributions

- Table