College of Nursing

58 Assessing Healthcare Disparities for Midlife Hispanic Women

Margaret Dalseth and Lisa Taylor-Swanson

Faculty Mentor: Lisa Taylor-Swanson (Nursing, University of Utah)

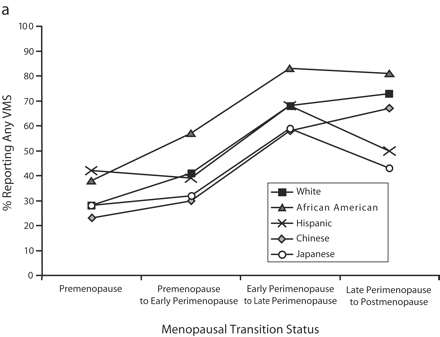

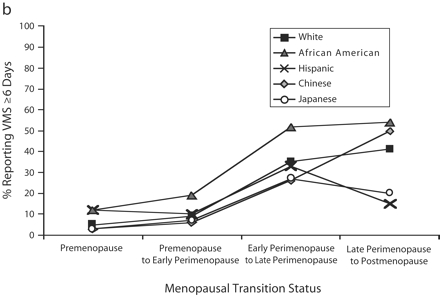

Vasomotor symptoms (VMS) such as hot flashes, night sweats, and palpitations manifest during pre-, peri-, and post-menopausal stages.1 According to the Study of Women Across the Nation (SWAN) Hispanic women report more negative experiences compared to other ethnic groups including VMS-related and depressive symptoms.2 SWAN is a multi-site longitudinal study examining the health of midlife women focusing on their biological, psychological, and social changes during this life period.3 Below, Graph A depicts the percent of the ethnic population that reports experiencing VMS for greater than 6 days and Graph B shows the percentage of specific populations that experience VMS in the preceding two weeks.2 Here, Hispanic women experience the greatest percentage of symptoms compared to other ethnicities during pre-menopause and the second highest experience of symptoms during perimenopause.2 More specifically, 45% of Hispanic women experience VMS during pre-menopause compared to 25% of White women.2 Many factors contribute to the increase in VMS experienced by Hispanic women such as nutritional risk factors and acculturation. To decrease the severity and frequency of VMS, Hispanic women may consider the increased inclusion of isoflavones which bind to estrogen receptors.4 Soy is rich in isoflavones, and studies show that soy supplementation reduces menopausal hot flashes.4 Since soy consumption is less a common part of Hispanic communities’ diets, messaging on soy consumption may aid in lowering VMS.5

Graph A. Percent of Women Presenting Vasomotor Symptoms for 6+ Days by Menopausal Status and Race/Ethnicity

Graph B. Percent of Women Presenting Vasomotor Symptoms for Greater than 2 weeks by Menopausal Status and Race/Ethnicity

One explanation for this disparity in symptoms is due to BMI.1 High BMI is specifically related to the increased prevalence of hot flashes, night sweats, and palpitations.1 SWAN reported that Hispanic women had one of the highest average BMIs which may contribute to their increase in experience of VMS.1 Similarly, high blood pressure is associated with the overactivity of the sympathetic nervous system (SNS) which stimulates adrenaline and sweat glands, contributing to the VMS experience.1 The US Hispanic population has similar prevalence of hypertension compared to White and Asian Americans but received an average of 7% less treatment compared to White Americans.6 The unmanaged potential for sympathetic nervous system overactivity places the Hispanic population at risk for VMS.

Not only are Hispanic women disproportionately affected by VMS but also major health risks associated with the onset of menopause.7 Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is the leading cause of death for menopausal and Hispanic women.8 Countless disparities exist relating to cardiovascular disease as Hispanics experience a greater burden of disease and CVD risk factors.9 For Hispanic women, there is also unawareness of CVD risk factors and mortality facts, late identification of risk factors, and inadequate education of appropriate response and recognition of threatening cardiac events.10 Sadly, due to this, 42.5% of US Hispanic women have CVD and it causes 28.3% of Hispanic female deaths.10 Contributing to these numbers are several risk factors including obesity, unfavorable lipid profiles, metabolic syndrome, and socioeconomic status (SES).10 Excess adiposity is a serious health problem for over three-quarters of US Hispanic women.10 Obesity is positively correlated with atherosclerotic plaque9 and fatty streaks9 along with psychological distress.12 Hispanic women are 65% more likely to have metabolic syndrome compared to non-Hispanic White women.10 Not only does the Hispanic female population have an increased likelihood of developing CVD due to disproportionate percentages of modifiable risk factors10 but their access to healthcare, healthcare coverage, and CVD education is significantly less compared to their White counterparts.13 Altman (2014) focused on culturally appropriate and relevant education tactics to reduce the knowledge gap regarding CVD in Hispanic women living in the US. The study achieved cultural relevance the intervention was primarily in Spanish, conscious of work schedules, and conducted yearlong research on culturally relevant tactics with a community advisory workgroup. The education series included heart health behavior education, CVD risk factor knowledge, and cardiac event awareness information.13 Throughout the 4-month program, there was nearly a 25% increase in the adoption of weight management programs, a decrease in modifiable risk factors such as hypertension, lipid profile, and obesity, and increased awareness of CVD risk factors and essential lifestyle changes.13 Alongside education, a focus on an anti-inflammatory diet may reduce the risk of cardiac-related events. For example, a diet including an assortment of leafy greens, dark yellow vegetables, and whole grains contains essential vitamins, antioxidants, and fiber that alter bodily inflammation, reducing CVD risk.14 Leafy greens contain indole-3-carbinol and phylloquinone which slow coronary artery calcium deposits and reduce systemic inflammation which are essential factors to decrease CVD.15 Incorporating 150 minutes (about 2 and a half hours) per week of physical activity also reduces the risk for a cardiac event.16 Physical activity improves insulin sensitivity, dyslipidemia, and blood pressure which are all factors that contribute to CVD risk.16 Overall, increasing education, anti- inflammatory diet components, and physical activity are essential for reducing CVD risk for the Hispanic population.

Another major health risk for women in the menopausal transition is osteoporosis, experienced by two-thirds of menopausal women.17 Hispanic women are 24% less likely compared to non- Hispanic women to receive osteoporosis-related healthcare including screening and post-fracture treatment.17 Type 2 diabetes was associated with a greater than twofold risk of developing osteoporosis due to increased osteoclast function, decreased osteoblast activity, and predisposition to falls because of diabetic neuropathy.17 Hispanic women over the age of 18 are 1.8 times more likely to be diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes compared to White women.18 Chronic kidney disease is also related to the onset of osteoporosis17,19 because of abnormal metabolism resulting in Vitamin D deficiency and adynamic bone (low bone turnover).17,20 Another risk factor is the lack of menopause hormone therapy (MHT) to increase estrogen levels in menopausal women.21 Estrogen is essential for the prevention of osteoporosis through the maintenance and formation of bone mass.22 These factors greatly exacerbate disparities in osteoporosis outcomes in the female Hispanic community. According to Noel (2020), Hispanic women following the DASH diet had the lowest likelihood of developing osteoporosis.23 Not only does the DASH diet include essential nutrient foods for bone health such as fruits, whole grains, legumes, and vegetables but the DASH recommendations are also low in sodium and moderate in low-fat dairy.23 The higher the sodium intake, the higher the amounts of calcium excreted in urine which leads to bone resorption to maintain blood calcium levels.23 In addition to low sodium preventing calcium excretion, it reduces the risk of Type 2 diabetes, a known risk factor for osteoporosis.23 Secondly, the emphasis on the consumption of low-fat dairy contributes to more favorable conditions for bone maintenance and formation.23

As discussed above, medical conditions are greatly influenced by metabolic syndrome, physical activity levels, and socioeconomic status – but they are also influenced by mental and stress states. The disproportionate amount of chronic stress Hispanic women face can be measured through allostatic load. Allostatic load is related to the framework that chronic stress causes physiological dysregulation24 causing physical deterioration altering cardiovascular and metabolic functioning.24, 25 Physiologic changes may be reflected through biochemical markers and secondary mediators including blood pressure, waist-to-hip-ratio, high density lipoprotein, cholesterol, and glycated hemoglobin.25 Since racial and ethnic minority groups such as Hispanic and Latina women experience a larger chronic stress load than Whites due to social disadvantages, they experience greater levels of allostatic load and adverse health effects. Chronic stress and high allostatic load is related to breast tumorigenesis, cancer mortality, and disease progression especially among postmenopausal women with a higher risk of developing breast cancer.26 Due to systematic inequalities, Hispanics experience a higher exposure to chronic stress and thus higher allostatic loads associated with more adverse health risks.26 This disparity may explain downstream effects on cancer rates for Hispanic women.

According to Shen, the prevalence of being a female Hispanic person with lower income was positively associated with cancer occurrence and allostatic load values.27

Many healthcare disparities exist for menopausal Latina women. Due to high metabolic syndrome rates, low socioeconomic status, high allostatic load, and societal barriers to healthcare, many Hispanic women experience decreased health in the menopausal transition. This manifests in worsened VMS, CVD, and osteoporosis.

Footnotes

- Tijerina A, Barrera Y, Solis-Pérez E, Salas R, Jasso JL, López V, et al. Nutritional Risk Factors Associated with Vasomotor Symptoms in Women Aged 40–65 Years. Nutrients [Internet]. 2022 Jun 22 [cited 2023 Mar 18];14(13):2587. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9268510/

- Green R, Santoro N. Menopausal Symptoms and Ethnicity: The Study of Women’s Health across the Nation. Women’s Health. 2009 Mar;5(2):127–33.

- SWAN: Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. SWAN Study. 2024.

- Gold E, Block G, Crawford S, Lachance L, FitzGerald G, Miracle H, Sherman S. Lifestyle and Demographic Factors in Relation to Vasomotor Symptoms: Baseline Results from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2004;159(12):1189-99.

- Reed S, Lampe J, Qu C, Gunderson G, Fuller S, Copeland W, Newton K. Self-reported menopausal symptoms in a racially diverse population and soy food consumption. Maturitas. 2013;75(2):152-8.

- Aggarwal R, Chiu N, Wadhera RK, Moran AE, Raber I, Shen C, et al. Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Hypertension Prevalence, Awareness, Treatment, and Control in the United States, 2013 to 2018. Hypertension [Internet]. 2021 Aug 9;78(6). Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.121.17570

- Weronika Adach, Kamila Ryczkowska, Janikowski K, Banach M, Agata Bielecka-Dąbrowa. Menopause and women’s cardiovascular health – is it really an obvious relationship? Archives of Medical Science [Internet]. 2022 Dec 10;19(2). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10074318/

- Currie H, Williams C. Menopause, Cholesterol and Cardiovascular Disease. European Cardiology Review. 2008;4(1):17.

- Barinas-Mitchell E, Duan C, Brooks M, El Khoudary SR, Thurston RC, Matthews KA, et al. Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factor Burden During the Menopause Transition and Late Midlife Subclinical Vascular Disease: Does Race/Ethnicity Matter? Journal of the American Heart Association. 2020 Feb 18;9(4).

- Hu J, Amirehsani KA, McCoy TP, Coley SL, Wallace DC. Cardiovascular disease risk in Hispanic American women. Women & Health. 2021 May 3;61(5):395–407.

- Powell-Wiley TM, Poirier P, Burke LE, Després JP, Gordon-Larsen P, Lavie CJ, et al. Obesity and Cardiovascular disease: a Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation [Internet]. 2021 Apr 22;143(21). Available from: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/ full/10.1161/CIR.0000000000000973

- Steptoe A, Frank P. Obesity and psychological distress. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B [Internet]. 2023 Sep 4;378(1888). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC10475872/

- Altman R, Nunez de Ybarra J, Villablanca AC. Community-Based Cardiovascular Disease Prevention to Reduce Cardiometabolic Risk in Latina Women: A Pilot Program. Journal of Women’s Health. 2014 Apr;23(4):350–7.

- Anti-inflammatory diets may reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease | NHLBI, NIH [Internet]. www.nhlbi.nih.gov.2020 [cited 2024 Jul 29]. Available from: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/news/2020/anti-inflammatory-diets-may-reduce-risk-cardiovascular-disease#:~:text=Anti%2Dinflammatory%20diets%20may%20reduce%20the%20risk%20of%20cardiovascular%20disease

- Depypere T, Comhair F. Herbal preparations for the menopause: Beyond isoflavones and black cohosh. Maturitas. 2014;77(2):191-94.

- Tian D, Meng J. Exercise for Prevention and Relief of Cardiovascular Disease: Prognoses, Mechanisms, and Apprcoaches. Oxidative Medicine and Cellular Longevity. 2019;2019(1).

- Ruiz-Esteves KN, Teysir J, Schatoff D, Yu EW, Burnett-Bowie SAM. Disparities in osteoporosis care among postmenopausal women in the United States. Maturitas. 2022 Feb;156:25–9.

- Kochanek K, Murphy S, Xu J, Arias E. National Vital Statistics Reports Deaths: Final Data for 2017 [Internet]. 2019. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/nvsr/nvsr68/nvsr68_09-508.pdf

- Vidal TM, Williams CA, Ramoutar UD, Haffizulla F. Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus in Latinx Populations in the United States: A Culturally Relevant Literature Review. Cureus [Internet]. 2022 Mar 15;14(3). Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC9009996/

- Coen, G. Adynamic bone disease: an update and overview. Journal of Nephrology. 2005;18(2):117-22.

- Zhao Na, Wei W, Xu Y, Li D, Yin B, Gu W. Role of menopausal hormone therapy in the prevention of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Central European Journal of Biology. 2023 Jan 1;18(1).

- Yarbrough MM, Williams DP, Allen MM. Risk Factors Associated with Osteoporosis in Hispanic Women. Journal of Women & Aging. 2004 Nov 23;16(3-4):91–104.

- Noel S, Mangano K, Griffith J, Dawson-Hughes B, Bigornia S, Tucker K. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension, Mediterranean, and Alternative Healthy Eating Indices are associated with bone health among Puerto Rican adults from the Boston Puerto Rican Osteoporosis Study. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 2020;111(6):1267-1277.

- Gallo LC, Jiménez JA, Shivpuri S, Espinosa de los Monteros K, Mills PJ. Domains of Chronic Stress, Lifestyle Factors, and Allostatic Load in Middle-Aged Mexican-American Women. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2010 Sep 29;41(1):21–31.

- Rodriquez EJ, Kim EN, Sumner AE, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. Allostatic Load: Importance, Markers, and Score Determination in Minority and Disparity Populations. Journal of Urban Health [Internet]. 2019 Jan 22;96(S1):3–11. Available from: https://link.springer.com/ article/10.1007/s11524-019-00345-5

- Wang F, Skiba MB, Follis S, Liu N, Bidulescu A, Mitra AK, et al. Allostatic load and risk of invasive breast cancer among postmenopausal women in the US Preventive Medicine [Internet]. 2024 Jan 1 [cited 2024 Jan 29];178:107817. Available from: https:// www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0091743523004036

- Shen J, Fuemmeler BF, Guan Y, Zhao H. Association of Allostatic Load and All Cancer Risk in the SWAN Cohort. Cancers. 2022 Jun 21;14(13):3044.

Media Attributions

- 137489262_066936.a1a_1

- 146879582_066936.a1b_1