College of Social and Behavioral Science

89 Listening to Midwives Working in an Informal Settlement in Kenya: Implications for Policy Making

Chrizelle Ransom and Marissa Diener

Faculty Member: Marissa Diener (Family and Consumer Studies, University of Utah)

Literature Review

Almost eight hundred women died every day in 2020 from preventable causes related to pregnancy and childbirth (World Health Organization [WHO], 2023). Ninety-five percent of those deaths occurred in middle to low-income countries. The World Health Organization has identified well-trained and educated midwives as capable of averting eighty percent of maternal deaths, stillbirths, and neonatal deaths (WHO, 2023).

In Kenya, over 83% of maternal and newborn care is provided by midwives (WHO, 2016). In 2014, the United Nations Population Fund estimated that the current Kenyan midwifery workforce will only meet 61% of the country’s needs by 2030 and that the nurse, midwife, and physician graduation rate would need to double in order to meet 97% of the need in the same year (United Nations Population Fund [UNFPA], 2014). Additionally, in the same report, a 9% midwifery attrition rate was noted, indicating a need to not only train new clinicians but also increase workforce retention.

Further convoluting the midwifery workforce landscape is low adherence to labor and delivery care quality standards (Impwii et al., 2023). In 2016 the World Health Organization released Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities, a document aimed at aiding maternal and infant healthcare workers in providing evidence- based routine and emergency care (WHO, 2016). Contributing factors leading to low adherence were overwhelming workloads, lack of appropriate supplies, lack of knowledge, and unavailability of physical copies of the standard-of-care documents in the facilities (Impwii et al., 2023). A review by Kimani & Gatimu (2023) agreed that outmigration and underinvestment exacerbate the midwifery workforce shortage in Kenya.

In 2013 the Kenya government aimed to improve access to maternal and infant healthcare for all citizens by removing all user fees associated with such care. This was known as the Linda Mama policy and was intended to cover prenatal, labor, and postpartum care. However, in practice, facilities were only reimbursed for labor costs, placing a strain on healthcare facilities (Orangi et al., 2021). Further, even though the Linda Mama Program resulted in certain improved maternal and infant outcomes, its existence and implementation have been politicized and uncertain (Ombere, 2024).

Even though there is tremendous focus on training clinically competent midwives, evidence suggests that midwives have little impact on national policies regarding maternal health. The third global State of the World’s Midwifery report identified investment in “midwife-led improvements in service delivery” as necessary to meet sustainable development goals (Nove et al., 2021). From a global perspective, midwives are minimally involved in policies regarding maternal health workforce planning and recognition of

midwifery as a profession, and its contributions are often limited (Lopes et al., 2015). In some

middle to low-income countries, midwives experience exclusion from policy-making circles. This is evidenced by midwives not being proportionately represented on advisory councils, and when they are represented in person, their names and contributions do not appear on policy documents (Acheampong et al., 2021).

Midwives are a key provider group when it comes to sexual, reproductive, maternal, and newborn health and have a unique capacity to influence policy development to achieve sustainable development goals. National policy leaders and decision-makers who come from the same professional backgrounds as their workforce often understand the challenges and intricacies of applying national standards in day-to-day operations. This can lead to more practical, relevant policies that support standard adherence while being realistic to the workforce’s experience (Matthews, 2012). Midwives should be involved in a “bottom-up” approach to policy-making and must be included in community and national leadership roles as they make up a significant portion of the “frontline workforce” (Etowa et al., 2023). Yet they are rarely involved in policy-making. It is not well understood why midwives are not involved in decision and policy making however, developing midwifery leadership is a consistent recommendation from global midwifery reports (Sattar et al., 2023).

Thus, the present study is a qualitative investigation designed to hear what midwives in Kenya think about issues relevant to their work and their perceptions of their capacity to exert influence on national maternal and infant health policies. The study is exploratory, and there are no specific hypotheses.

Method

Location and Context

The interviews were conducted at a community medical and birth clinic in an urban informal settlement on the outskirts of Nairobi, Kenya. The facility aims to provide evidence- based, respectful, and compassionate care to local residents. It provides full-spectrum prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care in addition to neonatal and child health services. The clinic is a private non-profit institution but receives some funding from the government. Patients are given appropriate treatment regardless of their ability to pay. The center also uses local and foreign donations to run its operations. Many patients opt for this clinic due to previous negative or traumatic obstetric experiences in public facilities. The center is basic and does not have surgical capacity, and this requires that higher-risk patients be referred to specialist care. However, the clinic regularly treats complex cases such as breech, multiples, labor dystocia, etc., out of necessity and the difficulty of transporting a patient to the nearest hospital over damaged and congested roads. Many patients who receive labor and birth care are not known to the clinic beforehand.

The exact location of the center is not disclosed to protect the privacy of the participants. The area has an average income of USD2 per day, poor road infrastructure, non-potable water, and most residents are day laborers who live hand-to-mouth. The area is known for its high crime rate, including sex-based violent crimes and robbery, and is listed as a crime “hot spot” by the Kenyan police service. In the past five years, economic living conditions have worsened for Kenyan residents due to three factors, namely, the COVID pandemic and its accompanying economic effects due to lock-downs (Development Initiatives, 2020), a current severe drought caused by four consecutive failed rainy seasons (USAID, 2024), and ongoing political instability and increased taxes on citizens (Biswas & Saha, 2022).

The investigator’s anecdotal experiences while in Kenya highlighted a few of the challenges experienced by Kenyan citizens. While traveling only 4 hours north of Nairobi, children and adults were seen begging for water by the roadside. USAID water stations are approximately 10-20 km apart, and tribal members have moved their families and herds to more central areas to gain access to water. Military checkpoints have been implemented to keep the peace between pastoralist militias and local citizens (ACLED, 2023). Local school administrators in Nairobi and Kitui counties reported to the investigator that parents cannot afford to pay even nominal school fees but will leave their children at the bus pickup spots so their children can have at least one meal at school. Finally, while driving in Nairobi, the investigator and a family member were stopped at a traffic police checkpoint and taken into custody for an unexplained traffic violation. They were taken to a local police station and asked for a cash bribe of USD80 and threatened with court proceedings if they did not comply. The issue was resolved over several days but served to highlight the duress of not only the citizens but also those of government employees. The investigator learned that police officers had not been paid their usual salary for approximately five months (Kinyanjui, 2023). A Kenyan friend of the investigator explained, “The police must also feed their families.” At the time the interviews were conducted, citizens were beginning to feel the effects of the new government’s tax bill. This tax bill led to deadly protests in 2024 (Ross et al., 2024).

Participants

Five midwives and one administrator were interviewed for this study (N=6). The administrator was included because they fulfill many duties akin to those of a midwife and have an intimate working knowledge of the patients’ lives and the maternal and infant health system in Kenya. Each midwife has a minimum of 4 years of applicable professional training and comes from various areas in and around Kenya. Three female and two male midwives were interviewed. Male midwives are not uncommon in Kenya. The midwives do not specialize and are cross-trained to provide comprehensive maternal care, including HIV/AIDS testing and counseling, contraceptive counseling, obstetric care, home visits, and basic medical care. All participants live within the community they serve and earn an average of USD 85 per month.

Procedure

The investigator is a Utah-licensed midwife and is acquainted with the founders of the clinic through international midwifery conferences. Her experience in maternal health provided her with insight to explore the research question, and her familiarity at the research site allowed shared rapport and trust with participants. It is possible that her positionality as a midwife influenced the research. Participants were recruited by inviting them to be interviewed. Inclusion criteria for participation were:

- Must be employed at the clinic.

- Must meet national midwifery education and training standards in Kenya.

- Must be proficient in the English language

University of Utah IRB approval was obtained. The IRB determined the study was low-risk and exempt. The IRB protocols are IRB_00167631 and IRB_00182075. An informed consent form was circulated digitally among midwifery staff. The midwives were assured that they were not obligated to participate in the study and that they could withdraw consent at any

time and/or decline to respond to specific questions without negative repercussions. At the start of each interview, verbal informed consent was gained. Each participant received USD8 for participating in an interview.

Interviews were conducted by the investigator in a quiet room at the clinic and lasted between forty to eighty minutes. Interviews were scheduled so as not to interfere with participants’ clinical duties or personal lives. Before each interview, the investigator first had an informal discussion with the participants to set them at ease and build rapport. Interviews were recorded on a digital device and saved using participant codes. Interviews were transferred to a secure cloud location. Interviews were transcribed by a professional third- party service knowledgeable in local Kenyan accents and dialects.

The interviews were semi-structured and contained sample questions to guide the conversation. Sample questions follow:

- Describe the path that led you to become a midwife.

- What do you love about being a midwife?

- What makes the care/service you provide different than can be expected in the public sector?

- What challenges do you face in your work as a midwife?

- What challenges do your patients face in the every-day life and pregnancy?

- Have you ever been invited by the local or national government to participate in policy- making discussions regarding maternal and infant health?

- What would you like your local and national leaders to understand about maternal and infant health in Kenya?

- What recommendations would you make for maternal and infant health?

- What specific measures or programs would you implement to improve maternal and infant health in Kenya?

Coding

An inductive coding process was applied to analyze face-to-face interview data. Initially, transcripts were reviewed multiple times to gain familiarity with the content. Open coding was used to identify patterns and recurring themes without predefined categories. Codes were iteratively refined and grouped into broader categories as the analysis progressed. Themes emerged organically from the data, leading to a structured framework that accurately reflected participants’ perspectives. This grounded, data-driven approach ensured that findings were closely tied to the lived experiences and perspectives shared during the interviews.

Results

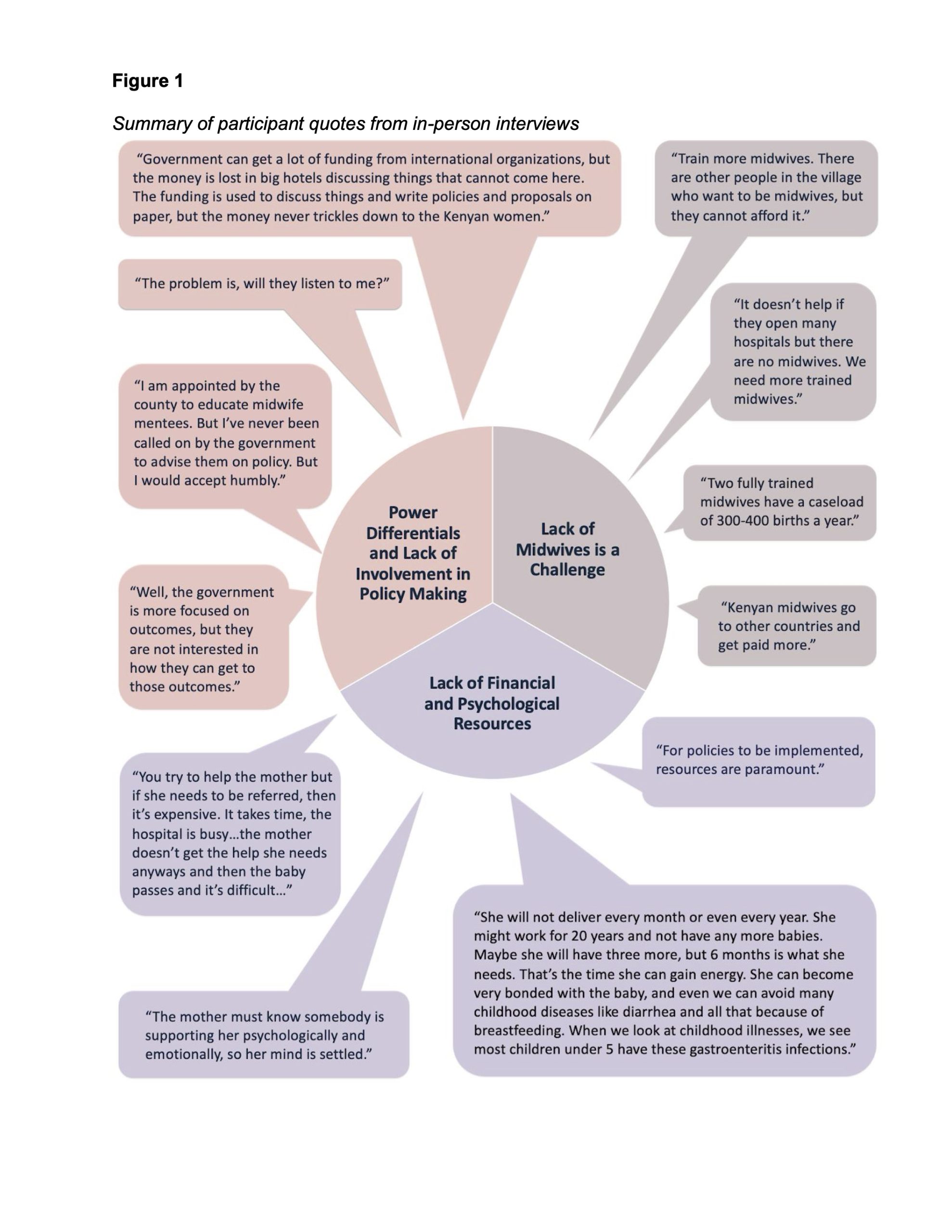

The qualitative analysis of the face-to-face interviews with midwives in Kenya yielded three major themes related to their perceptions of policy issues and their influence on maternal and infant health policies.

Lack of Financial and Psychological Resources

A recurring concern among participants was the insufficient financial and psychological support available to mothers. Midwife 4 explained that “These mothers disappear because of money,” highlighting how financial constraints often deter mothers from accessing essential health services. Midwife 5 emphasized the difficulty of navigating the referral system, noting,

“You try to help the mother, but if she needs to be referred, then it’s expensive. It takes time, the hospital is busy…the mother doesn’t get the help she needs anyways and then the baby passes and it’s difficult.”

It is clear that this midwife participant understands the link between the lack of timely and affordable healthcare and poor maternal and infant outcomes.

All participants expressed an understanding of the difficulty that many mothers face, with Midwife 3 explaining,

“They are doing some small work. They work like they want to get a daily meal. She has to work in the morning, and she comes late in the evening, so she cannot come for prenatal care. So now she cannot get all the information because of the nature of her work and unless she goes to work, she cannot eat because she has no one to support her now.”

The participants also stressed the importance of emotional and psychological support.

Midwife 4 stated, “The mother must know somebody is supporting her psychologically and emotionally, so her mind is settled.” This reflects the belief that stable mental well-being in mothers contributes to better health practices, such as receiving adequate prenatal care and breastfeeding, which can prevent poor birth outcomes and childhood illnesses.

While discussing subsidized maternity leave, another Midwife 3 pointed out that investment in maternal and infant health pays long-term dividends,

“She will not deliver every month or even every year. She might work for 20 years and not have any more babies. Maybe she will have three more, but 6 months is what she needs. That’s the time she can gain energy. She can become very bonded with the baby, and even we can avoid many childhood diseases like diarrhea and all that because of breastfeeding. When we look at childhood illnesses, we see most children under 5 have these gastroenteritis infections.”

One participant underscored that implementing health policies requires adequate resources, as summarized by the statement by Midwife 6, “For policies to be implemented, resources are paramount.”

Midwife Education and Training

Participants expressed a need for expanded training and education to enhance their scope of practice. Midwife 2 remarked, “More training to expand the scope,” signaling a desire for professional development. The participant went on to explain that she must routinely manage high-risk and emergent cases that would otherwise fall under the purview of a specialist in a well-resourced setting.

The inclusion of traditional birth attendants in healthcare policies was seen as an area for improvement, with Midwife 6 asking, “Why can’t we incorporate the traditional birth attendants in our policymaking rather than wiping them out, telling them it’s illegal?” This indicates a willingness to bridge traditional and formal healthcare practices to improve maternal outcomes.

The shortage of midwives was another significant concern. Midwife 4 highlighted the limitations of resources by saying, “Train more midwives. There are other people in the village who want to be midwives, but they cannot afford it.” This shortage was linked to the lack of adequate personnel in rural areas, where opening new healthcare facilities without sufficient staff was seen as ineffective. As one Midwife 2 pointed out, “It doesn’t help if they open many hospitals but there are no midwives. We need more trained midwives.” A key issue is the high workload, with Midwife 4 stating, “Two fully trained midwives have a caseload of 300-400 births a year.” Additionally, the migration of midwives to other countries for better opportunities was highlighted, with Midwife 1 noting, “Kenyan midwives go to other countries and get paid more.”

Power Differentials and Lack of Involvement in Policy Making

Participants expressed frustration over the lack of involvement in policy making, despite their direct experience with maternal and infant health. Midwife 6 shared concerns about the allocation of funds:

“Government can get a lot of funding from international organizations, but the money is lost in big hotels discussing things that cannot come here. The funding is used to discuss things and write policies and proposals on paper, but the money never trickles down to the Kenyan women.”

This statement reflects a sentiment that resources are often allocated to discussions rather than practical applications in the field.

There was also a sense of powerlessness, with Midwife 6 asking, “The problem is, will they listen to me?” despite their willingness to contribute to policy development. Midwife 4 described their limited role in advising policymakers, stating, “I am appointed by the county to educate midwife mentees. But I’ve never been called on by the government to advise them on policy. But I would accept humbly.” This lack of consultation contributed to a perception of neglect, as highlighted by the same midwife who said, “Our government has neglected our midwives.”

The focus on outcomes rather than processes was also critiqued, with Midwife 6 stating, “Well, the government is more focused on outcomes, but they are not interested in how they can get to those outcomes.” A lack of follow-through on existing policies was underscored with the observation, “The government has these policies and maternal booklets and protocols…but nothing is happening.” The maternal booklets the participant referred to are individual medical records that the patient carries with them through their pregnancy, with recommended scans, lab work, and supplements, but Midwife 1 explained, “They are supposed to buy supplements for a healthy pregnancy, and you know, they cannot even afford a meal.”

These findings illustrate the challenges midwives face in navigating the policy landscape, underscoring the need for increased involvement, resources, and training to improve maternal and infant health in Kenya.

Discussion

The purpose of this research study was to hear what midwives in Kenya think about issues relevant to their work and their perceptions of their capacity to exert influence on national maternal and infant health policies. The findings directly address this purpose, providing a detailed examination of the midwives’ experiences and perspectives.

The interviews revealed that many participants in the study feel disconnected from the national policy-making process, with some expressing frustration over their exclusion from critical discussions, which further supports the idea established by Lopes et al. (2015). This disconnect limits their ability to contribute to maternal and infant health policies that impact their daily practice. Despite their frontline role, midwives conveyed that they are rarely consulted or involved in the development of health policies, a theme that was particularly evident in their reflections on the allocation of resources. Consistent with a previous study (Orangi et al., 2021), one participant shared concerns that funds intended to improve maternal health often fail to reach local communities, underscoring a gap between policy formulation and its practical application. This insight highlights a broader systemic issue that directly relates to the study’s purpose, showing that while midwives possess critical insights into the healthcare landscape, their voices are not adequately included in policy creation (Acheampong et al., 2021).

The investigation also illuminated midwives’ perceptions of the current policy environment, particularly regarding the lack of financial and psychological support for mothers. This aligns with the broader policy challenge of integrating holistic care approaches into existing maternal health frameworks. The participants emphasized that effective policies should include both clinical and psychosocial components, demonstrating a sophisticated understanding of how comprehensive support can enhance maternal and child health outcomes. This important insight aligns with findings and assertions by Lasater et al. (2017). These perspectives suggest that midwives have a clear grasp of what policies are necessary for improving healthcare delivery, yet they feel sidelined in efforts to influence those policies.

Moreover, the study revealed midwives’ strong desire for increased training and professional development, particularly to manage complex cases in under-resourced settings.. This theme underscores the midwives’ awareness of policy deficiencies in education and training, further validating their potential role in shaping more effective health initiatives. By highlighting gaps in education and the need for a stronger, more inclusive healthcare framework (Nove et al., 2024), the study aligns with its purpose of understanding midwives’ policy-related perceptions.

Recommendations for policy

The current findings point toward possible recommendations to improve maternal and infant outcomes by focusing on three key areas, namely, increasing access to financial and psychological resources, midwifery training and staff retention, and including midwives at the highest level of maternal and infant health policy crafting.

Gaps in training and the real-life clinical skills required may be addressed by expanding midwifery training to include high-risk and emergency care, but the literature is sparse to support midwife training in high-risk obstetrics practices such as cesarean sections and neonatal intensive care. However, the integration of traditional birth attendants into the

existing maternal healthcare system is well supported by a systematic review of such policies in Nigeria (Hajaratu & Sunday, 2019). Accessibility to midwifery education should be improved through scholarships and financial support, particularly for those in rural areas, who often lack resources. Additionally, incentives for ongoing professional development are crucial to maintaining a skilled and adaptable workforce (Nove et al., 2024).

Retention efforts must address better compensation and working conditions to prevent midwife attrition (Van Lerberghe et al., 2014). Strategies include reasonable and reliable salaries reducing excessive workloads to prevent burnout. Recruitment of midwives in developing settings can be aided through various approaches, including reliable financial incentives and education; however, any initiative must have strong political and government support, be relatively simple in terms of scaling, and employ a direct-entry training model (Rosskam et al., 2013).

Many midwives highlighted that financial constraints significantly limit access to essential health services. To mitigate this, policy efforts should focus on expanding financial assistance for prenatal care, including labor laws that provide a pregnant or postpartum mother with sufficient time off to attend prenatal and postpartum care appointments and cover costs associated with referrals and specialized care (Richard, 2010). Additionally, implementing subsidized maternity leave would allow mothers to prioritize their health and the health of their child without the pressure of returning to work prematurely, fostering better outcomes for both mother and child. Investment in these areas not only enhances immediate maternal health but also reduces long-term childhood illnesses and healthcare expenditure through practices like breastfeeding, which a participant emphasized as vital for preventing conditions like diarrhea (Chai et al., 2024).

Equally important is the provision of psychological and emotional support for mothers. Midwives stressed the positive impact of mental well-being on maternal health practices, indicating that emotional support contributes to better prenatal care and child health. Policies should focus on providing consistent mental and social health services within maternal healthcare facilities, including counseling and peer support groups (Laseter et al., 2017). To ensure sustainability, investment in community-based support networks and training midwives in psychological care should be prioritized, allowing mothers to feel supported throughout the perinatal period and beyond.

It is also crucial to address the power differentials (Sriram, 2018) that limit midwives’ involvement in policy-making. Many midwives expressed frustration over the lack of consultation, despite their frontline experience in maternal care. To bridge this gap, policy recommendations should prioritize the inclusion of midwives at the highest levels of decision- making processes. Establishing formal advisory roles for midwives in county and national health policy discussions would ensure that their practical expertise is incorporated into effective policies informed by the lived experience of midwives. Additionally, redirecting a portion of international and government funding to grassroots consultations could provide midwives with a platform to influence policy development, making resource allocation more relevant to local needs (Clark et al., 2024).

Another key recommendation is to shift policy focus from outcomes to the processes that achieve them. Midwives expressed concerns that existing policies often overlook the steps necessary to improve maternal health, leading to inadequate follow-through. Therefore, policies should be designed with clear implementation guidelines and resources (Freedman et al., 2007) to implement these guidelines, regular evaluations, and feedback loops that actively involve midwives. This approach would not only empower midwives but also increase the accountability of all involved, ensuring that policy initiatives translate into tangible improvements in maternal care at the community level.

Recommendations for future research

The interviews were conducted in a private non-profit clinic that receives funding from the national and county governments which may limit the application of the investigation’s findings. However, the midwives interviewed had experience working in publicly funded facilities and expressed similar concerns. Future investigations should be conducted in public facilities in diverse settings, including large urban centers, rural healthcare centers, and small satellite facilities, to better understand the perceptions of all midwives working within Kenya.

The primary investigator is a midwife and is acquainted with research sites and staff midwives. Her training and shared professional experience allowed her to build rapport and trust with the participants, but her positionality may have impacted the research findings.

Furthermore, given the consistent themes of midwifery training and their exclusion from policy-making decisions, future investigations might explore leadership development within the Kenyan midwife workforce.

Conclusion

This qualitative investigation explored the perceptions of Kenyan midwives regarding issues relevant to their work and their capacity to exert influence on national maternal and infant health policies. The findings revealed a significant disconnect between midwives’ frontline experiences and the policy-making processes that shape maternal healthcare in Kenya. Despite their comprehensive understanding of the challenges faced by mothers and their own crucial role in providing care, midwives felt excluded from policy development.

Their voices are rarely heard in discussions about resource allocation, training programs, or strategies to improve maternal and infant health outcomes. This lack of involvement limits the effectiveness of policies, as crucial insights from the field are often overlooked.

Addressing this gap requires a fundamental shift in how midwives are perceived and engaged within the Kenyan healthcare system. Policy recommendations should prioritize the inclusion of midwives in decision-making processes at both the county and national levels.

Establishing formal advisory roles for midwives, directing funding towards grassroots consultations, and emphasizing the implementation processes would empower midwives to shape policies that are both practical and responsive to the needs of mothers and infants. Investing in midwifery education and training, addressing the workforce shortage, and providing adequate financial and psychological support to mothers are crucial steps towards achieving sustainable improvements in maternal and infant health in Kenya.

References

Acheampong, A. K., Ohene, L. A., Asante, I. N., Kyei, J., Dzansi, G., Adjei, C. A., Adjorlolo, S., Boateng, F., Woolley, P., Nyante, F., & Aziato, L. (2021). Nurses’ and midwives’ perspectives on participation in National Policy Development, review and reforms in Ghana: A qualitative study. BMC Nursing, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00545-y

Acheampong, A. K., Ohene, L. A., Asante, I. N., Kyei, J., Dzansi, G., Adjei, C. A., Adjorlolo, S., Boateng, F., Woolley, P., Nyante, F., & Aziato, L. (2021). Nurses’ and midwives’ perspectives on participation in National Policy Development, review and reforms in Ghana: A qualitative study. BMC Nursing, 20(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-021-00545-y

Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED). (2023, August 4). Kenya situation update: August 2023 – Government operation brings calm to North Rift region. ACLED. https://acleddata.com/2023/08/04/kenya-situation-update-august-2023-government-operation-brings-calm-to-north-rift-region/

Biswas, S., & Saha, A. (2022). Impact of COVID-19 on the global economy: An empirical analysis. Economies, 10(8), Article 191. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies10080191

Chai, Y., Nandi, A., & Heymann, J. (2024). Is the impact of paid maternity leave policy on the prevalence of childhood diarrhoea mediated by breastfeeding duration? A causal mediation analysis using quasi-experimental evidence from 38 low-income and middle-income countries. BMJ Open, 14, e071520. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2022-071520

Clark, E. C., Baidoobonso, S., Phillips, K. A. M., Noonan, L. L., Bakker, J., Burnett, T., Stoby, K., & Dobbins, M. (2024). Mobilizing community-driven health promotion through community granting programs: a rapid systematic review. BMC Public Health, 24(1), 932. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-024-18443-8 Development Initiatives. (2020). Socioeconomic impacts of COVID-19 in Kenya.

Development Initiatives. https://devinit-prod-static.ams3.cdn.digitaloceanspaces.com/media/documents/Socioeconomic_impacts_of_Covid-19_in_Kenya.pdf

Etowa, J., Vukic, A., Aston, M., Iduye, D., Mckibbon, S., George, A., Nkwocha, C., Thapa, B., Abrha, G., & Dol, J. (2023). Experiences of nurses and midwives in policy development in low- and middle-income countries: Qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 5, 100116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2022.100116

Etowa, J., Vukic, A., Aston, M., Iduye, D., Mckibbon, S., George, A., Nkwocha, C., Thapa, B., Abrha, G., & Dol, J. (2023). Experiences of nurses and midwives in policy development in low- and middle-income countries: Qualitative systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 5, 100116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2022.100116

Freedman, L. P., et al. (2007). Practical lessons from global safe motherhood initiatives: Time for a new focus on implementation. The Lancet, 370(9595), 1383–1391.

Hajaratu, U. S., & Sunday, A. E. (2019). Integration of traditional birth attendants (TBAs) into the health sector for improving maternal health in Nigeria: A systematic review.

Sub-Saharan African Journal of Medicine, 6(2), 55-62. https://doi.org/10.4103/ssajm.ssajm_25_17 Impwii, D. K., Kivuti-Bitok, L., & Karani, A. (2023). Adherence to labor and delivery care quality standards and associated factors among nurse-midwives in two public teaching and referral hospitals in Kenya: a cross-sectional survey. The Pan African medical journal, 45, 149. https://doi.org/10.11604/pamj.2023.45.149.36943

Kimani, R.W. & Gatimu, S.M. (2023) Nursing and midwifery education, regulation and workforce in Kenya: A scoping review. International Nursing Review, 70, 444–455. https://doi-org.ezproxy.lib.utah.edu/10.1111/inr.12840

Kinyanjui, M. (2023, April 11). Ruto breaks silence over delayed salaries of public servants. The Star. https://www.the-star.co.ke/news/2023-04-11-ruto-breaks-silence-over-delayed-salaries-of-public-servants#google_vignette

Lasater, M. E., Beebe, M., Gresh, A., Blomberg, K., & Warren, N. (2017). Addressing the Unmet Need for Maternal Mental Health Services in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Integrating Mental Health Into Maternal Health Care. Journal of midwifery & women’s health, 62(6), 657–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/jmwh.12679

Lopes, S. C., Titulaer, P., Bokosi, M., Homer, C. S., & ten Hoope-Bender, P. (2015). The involvement of Midwives Associations in policy and planning about the midwifery workforce: A global survey. Midwifery, 31(11), 1096–1103. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.07.010

Matthews, J. H. (2012). Role of professional organizations in advocating for the nursing profession. OJIN: The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 17(1). https://ojin.nursingworld.org/MainMenuCategories/ANAMarketplace/ANAPeriodicals/OJIN/TableofContents/Vol-17-2012/No1-Jan-2012/Professional-Organizations-and-Advocating.html

Nove, A., ten Hoope-Bender, P., Boyce, M. et al. The State of the World’s Midwifery 2021 report: findings to drive global policy and practice. Human Resources and Health 19, 146 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-021-00694-w

Nove, A., Boyce, M., Neal, S., & et al. (2024). Increasing the number of midwives is necessary but not sufficient: Using global data to support the case for investment in both midwife availability and the enabling work environment in low- and middle- income countries. Human Resources for Health, 22(54). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12960-024-00925-w

Ombere, S. O. (2024). Can “the expanded free maternity services” enable Kenya to achieve universal health coverage by 2030: Qualitative study on experiences of mothers and healthcare providers. Frontiers in Health Services, 4, Article 1325247. https://doi.org/10.3389/frhs.2024.1325247

Orangi, S., Kairu, A., Malla, L., Ondera, J., Mbuthia, B., Ravishankar, N., & Barasa, E. (2021). Impact of free maternity policies in Kenya: an interrupted time-series analysis. BMJ global health, 6(6), e003649. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjgh-2020-003649

Richard, F., Witter, S., & de Brouwere, V. (2010). Innovative approaches to reducing financial barriers to obstetric care in low-income countries. American Journal of Public Health, 100(10), 1845–1852. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.179689

Ross, A., Obulutsa, G., & Paravicini, G. (2024, June 25). Police fire on demonstrators trying to storm Kenya parliament, several dead. Reuters. https://www.reuters.com/world/africa/young-kenyan-tax-protesters-plan-nationwide-demonstrations-2024-06-25/

Rosskam, E., Pariyo, G., Hounton, S., & Aiga, H. (2013). Increasing skilled birth attendance through midwifery workforce management. The International journal of health planning and management, 28(1), e62–e71. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.2131

Sattar, S. M., Akeredolu, O., Bogren, M., Erlandsson, K., & Borneskog, C. (2023). Facilitators influencing midwives to leadership positions in policy, Education and practice: A systematic integrative literature review. Sexual & reproductive healthcare: Official Journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives, 38, 100917. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2023.100917

UNFPA. (2014). The state of the world’s midwifery 2014: A universal pathway. A woman’s right to health (pp. 118-119). UNFPA.

USAID. (2024, August). USAID-BHA Kenya assistance overview: August 2024. USAID. https://www.usaid.gov/sites/default/files/2024-09/USAID- BHA_Kenya_Assistance_Overview-August_2024.pdf

Van Lerberghe, W., Matthews, Z., Achadi, E., Ancona, C., Campbell, J., Channon, A., … & Turkmani, S. (2014). Country experience with strengthening of health systems and deployment of midwives in countries with high maternal mortality. The Lancet, 384(9949), 1215-1225.

Veena Sriram, Stephanie M Topp, Marta Schaaf, Arima Mishra, Walter Flores, Subramania Raju Rajasulochana, Kerry Scott, 10 best resources on power in health policy and systems in low- and middle-income countries. Health Policy and Planning, 33, Issue 4, May 2018, Pages 611–621, https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czy008

World Health Organization. (2016a). Global strategic directions for strengthening nursing and midwifery 2016-2020. World Health Organization.

World Health Organization. (2016b). Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/mca-documents/qoc/quality-of-care/standards-for-improving-quality-of-maternal-and-newborn-care-in-health-facilities.pdf

World Health Organization. (2023a). Strengthening quality midwifery for all mothers and Newborns. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/activities/strengthening-quality-midwifery-for-all-mothers-and-newborns

World Health Organization. (2023b, February 22). Maternal mortality. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/maternal-mortality

Media Attributions

- 55776342_chrizelle_ransom_midwives_final_