Spencer Fox Eccles School of Medicine

45 Are Recommendations Made by Clinical Guideline Committees Impacted by Psychological Biases? – A Retrospective Evaluation of Clinical Guidelines

Gabriel LaBrin; Valerie Vaughn; and Andrea White

Faculty Mentor: Valerie Vaughn (Internal Medicine, University of Utah)

Introduction

National clinical guidelines are vital to shaping clinician action and patient care in the healthcare setting and beyond[1,2]. Guidelines provide recommendations for diagnosis, screening, treatment, and care for specific areas related to the subject of the guideline[3]. Guidelines were created in part to cure medical conditions and ensure that care, whether it be a drug, device, procedure, or other treatment, not be over or under-provided. Clinical practice guideline-developing groups may be subject to bias[4,5] due to the inherent characteristics of humans, despite disclosure of conflicts[6-9]. In light of this, guidelines must continue to be examined for impartiality to ensure patients receive quality, unbiased care.

When guidelines are created and updated, the evidence assembled must be reviewed[10-12] consistently and transferred seamlessly to a corresponding recommendation. This process is guided through methodologies[13-15] such as the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development, and Evaluations (GRADE) which provide a rating system for evidence quality and recommendations but might not eliminate human biases. Despite systemic processes, recommendations are often made (necessarily) with incomplete or low-quality evidence. In situations of uncertainty, limited or imperfect evidence, and high stakes (e.g., patient care), decision-making is particularly susceptible to cognitive biases.

Two examples of cognitive biases potentially present in developing clinical guidelines are the action bias[16-18] and social norm bias[19-23]. The action bias[16] is the tendency to favor action over inaction]. In clinical settings, the action bias may be particularly hard to resist as inaction is often perceived as giving up on or neglecting patients, but taking a course of action backed by little evidence or associated with potential harm may not be a helpful move. Contrarily, it can be difficult to change a person’s mind, allowing the social norm bias could influence the development of clinical guidelines by requiring more evidence than necessary to halt or decrease a practice. Furthermore, if any relevant articles and/or studies are not included as evidence for the guideline to begin with, there may be a trace of publication bias[24,25] within the development of the guidelines.

Therefore, we aimed to assess if biases were present in guidelines by using IM guidelines and analyzing whether or not in national internal medicine clinical guidelines, recommendations that an existing practice be decreased or stopped have different supporting evidence than recommendations that a practice be augmented or new practice started. We hypothesize that a recommendation to start or increase an existing practice will require a lower amount and quality of evidence and that decreasing or stopping an existing practice will require a higher amount and quality of evidence.

Methods

In this bibliometric study of internal medicine society guidelines, we determined whether the strength and amount of evidence cited by society guidelines differed based on whether societies were recommending adding a new practice, continuing an existing practice, or stopping an existing practice. Articles eligible for inclusion were societal guidelines published from January 1st, 2014 to June 1st, 2024, and created by a US-based internal medicine specialty society.

Sample Inclusion

To identify US-based internal medicine specialties, two authors reviewed the Council of Medical Speciality Societies[26] (CMSS) list of medicine specialties. Non-internal medicine specialty societies were excluded. The final list of 19 internal medicine specialties was reviewed in random order (using a random number generator) until 10 total societies were included. To be included, societies had to have published official clinical guidelines within the last 10 years. Societal guidelines were identified via the official society websites.

Once 10 societies were randomly selected for inclusion, we randomly chose 1 guideline from each society to review. Guidance statements, best practice statements, endorsed clinical guidelines (i.e., guidelines created by another society but endorsed by a specific specialty society being looked at), guidelines that were still under development, guidelines for which the most recent addition was before 2014(more than ten years ago), or guidelines addressed to professions other than health-care providers were excluded. To ensure we were able to assess changes in recommendations (i.e., whether the recommendation was new vs. existing practice), we excluded clinical guidelines that did not have a similar guideline previously published by the society.

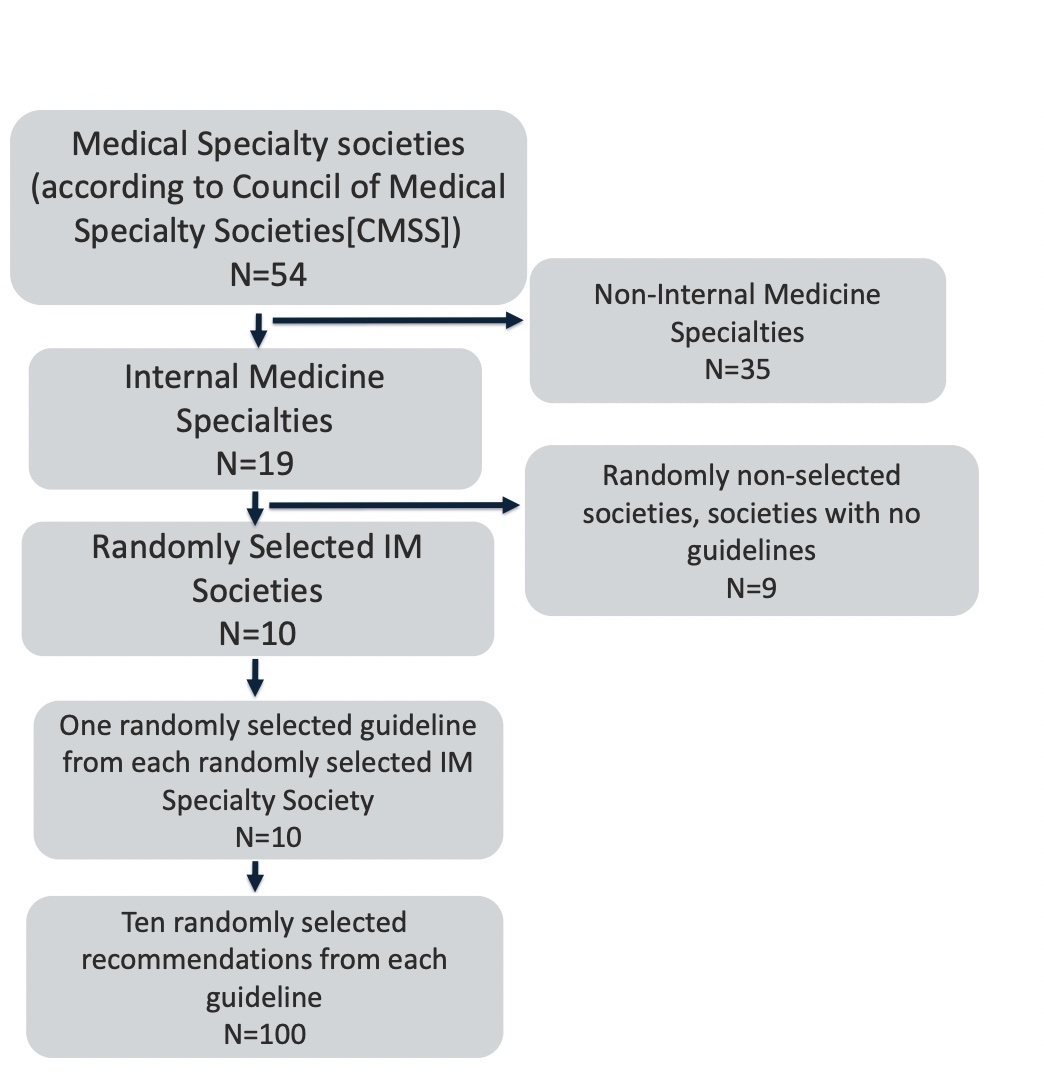

Finally, for each of the 10 randomly selected guidelines, we chose 10 recommendations each using a random number generator. If a guideline had fewer than ten recommendations, we reviewed all recommendations from that guideline. These methods may also be viewed in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Summary of Recommendation Inclusion

Data Collection

Data were collected independently and in duplicate by two study authors using REDCap. Discrepancies were resolved through consensus with a third reviewer serving as a tie-breaker in case of disagreements.

Primary Outcome

Our primary outcome was an ordinal outcome assessing whether each recommendation was starting a new practice vs. stopping an existing practice. The 5-point ordinal scale was:

1. starting a new practice

2. Increasing an existing practice

3.Continuing an existing practice

4.Decreasing an existing treatment

5. Stopping an existing treatment.

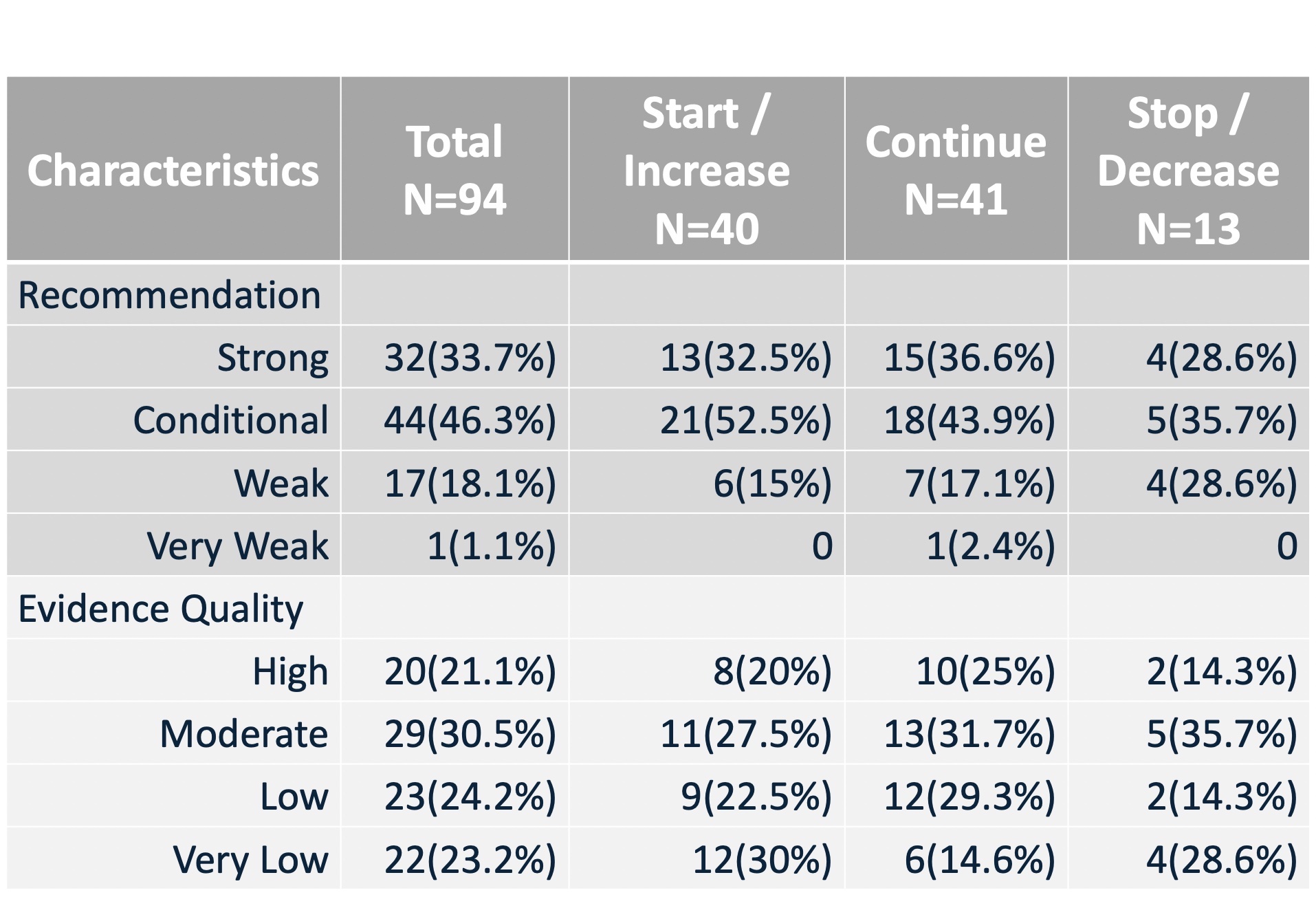

Starting a new treatment was defined as a society recommending a treatment that had not been recommended and/or mentioned in the previous guideline. Stopping an existing treatment was defined as a society recommending to stop a treatment that had been recommended in a previous guideline. Increase, continue, and decrease were used for recommendations that increased, continued, or decreased a treatment given in the previous guideline. These categories are portrayed in Table 1.

Variables of Interest

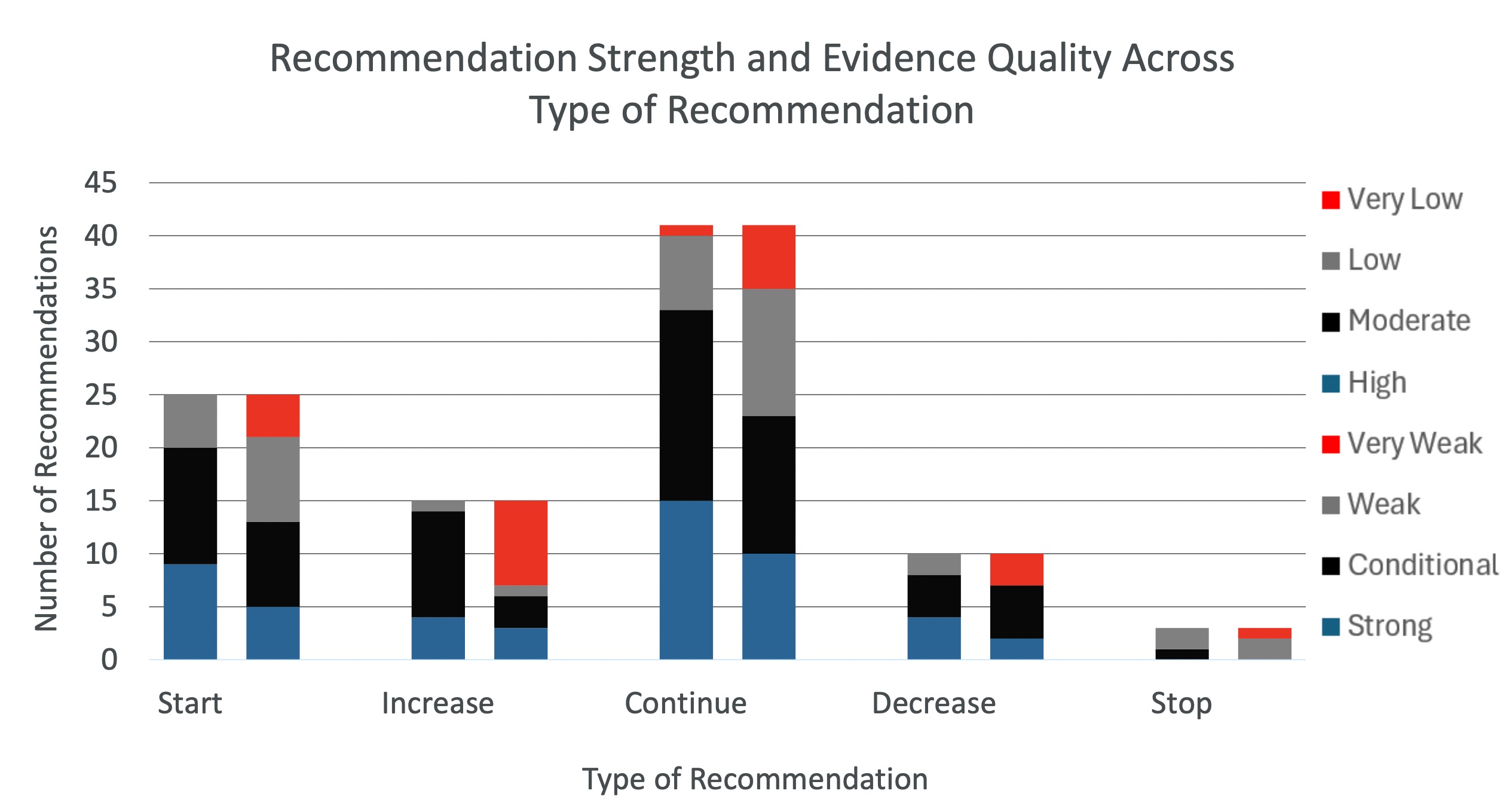

Secondary outcomes were acquired using the REDCap and were defined as: a) quality of evidence (i.e. high, moderate, low, very low), b) number of studies cited as evidence for a recommendation, c) type of evidence (e.g., systematic review, clinical trial, observational only), and d) strength of recommendation (i.e. strong, conditional, weak, very weak). These categories are visible in Table 1. and Figure 2.

Table 1. Characteristics of Recommendations

Potential confounders

In addition to primary and secondary outcomes, we collected guideline characteristics (e.g., year of publication, society), reported processes for evidence synthesis (e.g., use of GRADE, use of patient perspectives), and details about the specific recommendation (e.g., type of recommendation–drug, device, behavior, procedure, or quality improvement implementation).

IRB approval

This project included only publicly accessible data and was thus deemed exempt from review by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board.

Results

Of the total sample of recommendations reviewed, 81/94(85.2%) of the recommendations were for any of starting a treatment(25/94[26.6%]), increasing a treatment(15/94[15.9%]), or continuing a treatment(41/95[43.2%]). This leaves just 13(14.8%) of the recommendations as recommendations for decreasing (8/94[8.5%]) or stopping (3/94[3.2%]). 32(33.7%) of recommendations were strong, 44(46.3%) were conditional, 17(18.1%) were weak, and 1(1.1%) were very weak. 20(21.1%) of the evidence was graded high, 29(30.5%) were graded conditionally, 23(24.2%) were low, and 22(23.2%) were very low. Thus, 85% of recommendations were recommending action of a sort, with a potentially significant portion of these actions being recommended based on an evidence basis containing a significant portion of low and very low-quality evidence(47%).

Discussion

Healthcare providers always strive to provide the best quality care for their patients. Oftentimes when a patient comes into the hospital they expect action to be taken to help them recover from or deal with whatever they are arriving at the hospital with, and oftentimes the best course of treatment to help care for a patient is to take action. However, where the action bias comes in is when patients or healthcare providers assume that any lessening of treatment or absence of treatment is always a detrimental form of care that will harm patients[27]. We know that there are situations in which this is not true, such as antibiotic stewardship[28,29]. Based on our results, specifically that action is being recommended 85% of the time in clinical guidelines on the basis of a dataset which is 47% low or very low, there are many instances in which action is being taken based on poor or very poor evidence.

Additionally, if history has anything to say, these numbers should be examined and remedied in an urgent manner. Many harmful treatments have made their way through patient populations in the past, with examples including morphine, heroin, tobacco, fake snake oils, mercury treatment, bloodletting, and even cannibalism[30-32]. These are very extreme examples, but time and time again, medical treatments have become established parts of clinicians’ treatment regimens only to fall out of favor once the real effects come to light. In light of this pattern throughout medical history and our gathered data, we believe that national clinical guideline-creating committees should consider this trend and strive to mitigate risks caused by potentially harmful or unnecessary treatments recommended for patient care based on low or very low-quality evidence.

Conclusion

Despite most evidence for current practices being conditional or weak and based on low/very lowquality evidence, internal medicine guidelines rarely recommend existing practices be stopped or decreased—suggesting that action bias and social norm bias are at play. National guidelines should specifically consider what existing practices and treatments are being recommended based on lowquality evidence, and which of these recommendations may be causing more harm than good to patients.

Footnotes

1. Murad MH. Clinical practice guidelines – Mayo Clinic Proceedings. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. March 2017. Accessed June 24, 2024. https://www.mayoclinicproceedings.org/article/ S0025-6196(17)30025-3/fulltext.

2. Balas EA, Boren SA. Managing clinical knowledge for health care improvement. Scholarly Commons Home Page. January 1, 2000. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://augusta.openrepository.com/ handle/10675.2/617990

3. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Lin JS, Mustafa RA, Wilt TJ. The development of clinical guidelines and guidance statements by the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians: Update of methods | annals of internal medicine. ACP Journals. June 11, 2019. Accessed May 29, 2024. https://www.acpjournalhttps://www.acpjournals.org/doi/full/10.7326/M18-3290s.org/doi/full/ 10.7326/M18-3290

4. Blumenthal-Barby JS, Krieger H. Cognitive biases and heuristics in medical decision making: a critical review using a systematic search strategy. Med Decis Making. 2015;35(4):539-557. doi:10.1177/0272989X14547740

5. Detsky AS. Sources of bias for authors of Clinical Practice Guidelines. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;175(9):1033-1033. doi:10.1503/cmaj.061181

6. Kunz A. Managing conflict of interest disclosure-where are we going? Science Editor. December 11, 2019. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://www.csescienceeditor.org/article/managing-conflict-ofinterest-disclosure-where-are-we-going/.

7. Mann S. Convey: A new system to simplify the process for disclosing financial interests. AAMC. September 27, 2016. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://www.aamc.org/news/convey-new-systemsimplify-process-disclosing-financial-interests.

8. What is open payments? CMS.gov. April 8, 2024. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://www.cms.gov/ priorities/key-initiatives/open-payments.

9. ICMJE form for disclosure of potential conflicts of interest. SAGE Journals. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://journals.sagepub.com/pb-assets/cmscontent/HPO/coi_disclosure.pdf.

10. Atkins L, Smith JA, Kelly M p, Michie S. The process of developing evidence-based guidance in medicine and public health: A qualitative study of views from the inside – implementation science. BioMed Central. September 4, 2013. Accessed June 7, 2024. https:// implementationscience.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1748-5908-8-101

11. Fretheim A, Schünemann HJ, Oxman AD. Improving the use of research evidence in guideline development: 3. group composition and consultation process. Health research policy and systems. November 29, 2006. Accessed June 26, 2024. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/ PMC1702349/.

12. Moreira Ti. Diversity in clinical guidelines: The role of repertoires of evaluation. Social Science & Medicine. November 16, 2004. Accessed June 7, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/ pii/S0277953604004733?via%3Dihub.

13. Siemieniuk R, Guyatt G. What is GRADE? BMJ Best Practice. 2024. Accessed May 28, 2024. https://bestpractice.bmj.com/info/us/toolkit/learn-ebm/what-is-grade/#:~:text=GRADE%20(Grading%20of%20Recommendations%2C%20Assessment,for%20making%20 clinical%20practice%20recommendations.

14. Guyatt GH, Balshem H. The grade approach is reproducible in assessing the quality of evidence of quantitative evidence syntheses. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. April 23, 2013. Accessed August 2, 2024. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0895435613000577?via%3Dihub.

15. Brouwers MC, Spithoff K, Kerkvliet K, et al. Development and validation of a tool to assess the quality of Clinical Practice Guideline Recommendations. JAMA Network Open. 2020;3(5). doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.5535

16. Pilat D, Krastev S. Action bias. The Decision Lab. Accessed June 7, 2024. https:// thedecisionlab.com/biases/action-bias.

17. Ayanian JZ, Berwick DM. Do physicians have a bias toward action? A classic study revisited. Med Decis Making. 1991;11(3):154-158. doi:10.1177/0272989X9101100302

18. Kiderman A, Ilan U, Gur I, Bdolah-Abram T, Brezis M. Unexplained complaints in primary care: evidence of action bias. J Fam Pract. 2013;62(8):408-413.

19. Kressel LM, Chapman GB. The default effect in end-of-life medical treatment preferences. Med Decis Making. 2007;27(3):299-310. doi:10.1177/0272989X07300608 Kressel LM,

20. Chapman GB, Leventhal E. The influence of default options on the expression of end-of-life treatment preferences in advance directives. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(7):1007-1010. doi:10.1007/ s11606-007-0204-6

21. Richards AR, Linder JA. Behavioral Economics and Ambulatory Antibiotic Stewardship: A Narrative Review. Clin Ther. 2021;43(10):1654-1667. doi:10.1016/j.clinthera.2021.08.004

22. Halpern SD, Ubel PA, Asch DA. Harnessing the power of default options to improve health care. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(13):1340-1344. doi:10.1056/NEJMsb071595

23. Patel MS, Volpp KG, Asch DA. Nudge Units to Improve the Delivery of Health Care. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jan 18;378(3):214-216. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1712984. PMID: 29342387; PMCID: PMC6143141.

Media Attributions

- Screenshot

- Screenshot

- Screenshot