College of Social and Behavioral Science

96 Building the Data Infrastructure for Research on Labor Market Institutions’ Effects on Population Health

Jeb Wu and Megan Reynolds

Faculty Mentor: Megan Reynolds (Sociology, University of Utah)

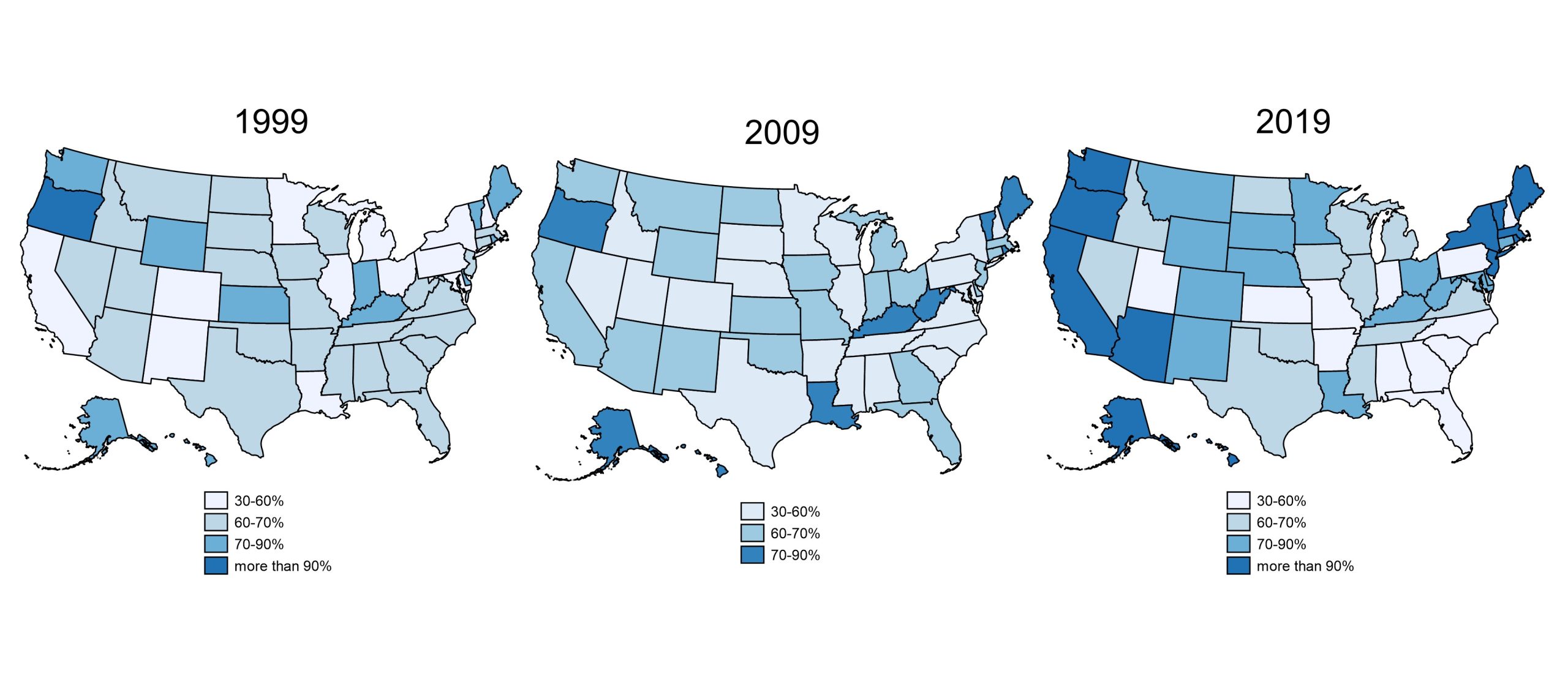

In 2014, the US recorded its first drop in life expectancy in half a century, with rising mortality rates concentrated among working-age adults. Not only does this decrease the size of the American labor force and consequent levels of national productivity, but the diseases associated with these deaths (cardiometabolic, external causes) decrease the quality of life for everyone else. Meanwhile, we have witnessed the power of American labor significantly eroding since 1980, with the dissolution of labor market institutions (LMIs) that counteracted the shifting of risk from employers to workers. A potential source of relief for workers comes in the form of LMI generosity (LMIG), policies such as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), union premiums, and minimum wages. While LMIG could provide the financial assistance that otherwise may compromise the health of individuals, there is not a comprehensive measure of labor market protections and their effects. In this project, we create this comprehensive measure and then examine its relationship with population health in different states of varying levels of LMIGs. We create this comprehensive measure by determining the LMIG and its effect by matching it to population health in different states. In my specific sect of project, I established what those state-level health profiles were, then matched the results to LMIGs per state (see Fig. 1).

Before I could begin determining the effect, however, I first had to find suitable sources for state-level health outcomes. We use state-level health outcomes specifically because in addition to yearly shifts in the cost of living, LMIG can vary greatly depending on the state (due to partisanship, demographics, etc). Much of the present public health data on this subject exists on an individual level, or only for specific select years. Hence, I first had to do a brief overview search for relevant, raw data sets by constructing a Data Inventory, and I inevitably landed on the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), a state-based system of telephone health surveys that collects information on health risk behaviors, preventive health practices, and health care access primarily related to chronic disease and injury. BRFSS was identified as the best source for mid-life, working-age adults because it provides yearly data, every state receives a relatively equal distribution of surveys, and it tracks demographics. We want to track that demographic data to determine whether or not there is a greater impact that LMIG has on certain disenfranchised groups as these programs are specifically designed to assist them.

According to prior research done by Professor Reynolds and other contemporaries (Han), more disadvantaged groups likely reap larger returns from social policy investments because of differences in the structure of their resource base. Though this provides a potential argument and hypothesis for the results of our research, we have yet to establish whether LMIG differentially affects mothers at additional disadvantage, namely those in extreme poverty, those without a high-school degree, those who are Black, and those who are unmarried.

With the aid of Professor Reynolds, this data set was merged and appended year by year to achieve the basic health statistics for hypertension, diabetes, myocardial infraction, stroke, heart disease, blood cholesterol, self-rated health, and substance abuse, which will go on in determining the effect of LMIG per state. While the BRFSS gives broad, detailed statistics regarding state-level health profiles, it only covers working-age adult health statistics. The future progression of this specific study aims to add in state-level health profiles for both infants and adults age 65+ to understand the broader-scope implications of LMIGs. By exploring the extent to which LMIGs benefit individuals as well as which individuals they benefit, this project could aid in the creation of economic policy promoting a more robust labor force and improved quality of life across segments of the American population.  Figure 1

Figure 1

Bibliography

Center for Disease Control and Prevention, BRFSS 1999-2019 Survey Data and Documentation. (n.d.). https://www.cdc.gov/brfss/annual_data/annual_data.htm

Han, X., VanHeuvelen, T., Mortimer, J. T., & Parolin, Z. (2024). Cumulative Unionization and Physical Health Disparities among Older Adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 65(2), 162-181. https://doi.org/10.1177/00221465231205266

Media Attributions

- 137489262_spur2024-jebwu-range_image