College of Social Work

98 A National Exploratory Study on Housing Services for Survivors of Human Trafficking

Lydia Altamiranda and Lindsay Gezinski

Faculty Mentor: Lindsay Gezinski (Social Work, University of Utah)

Abstract

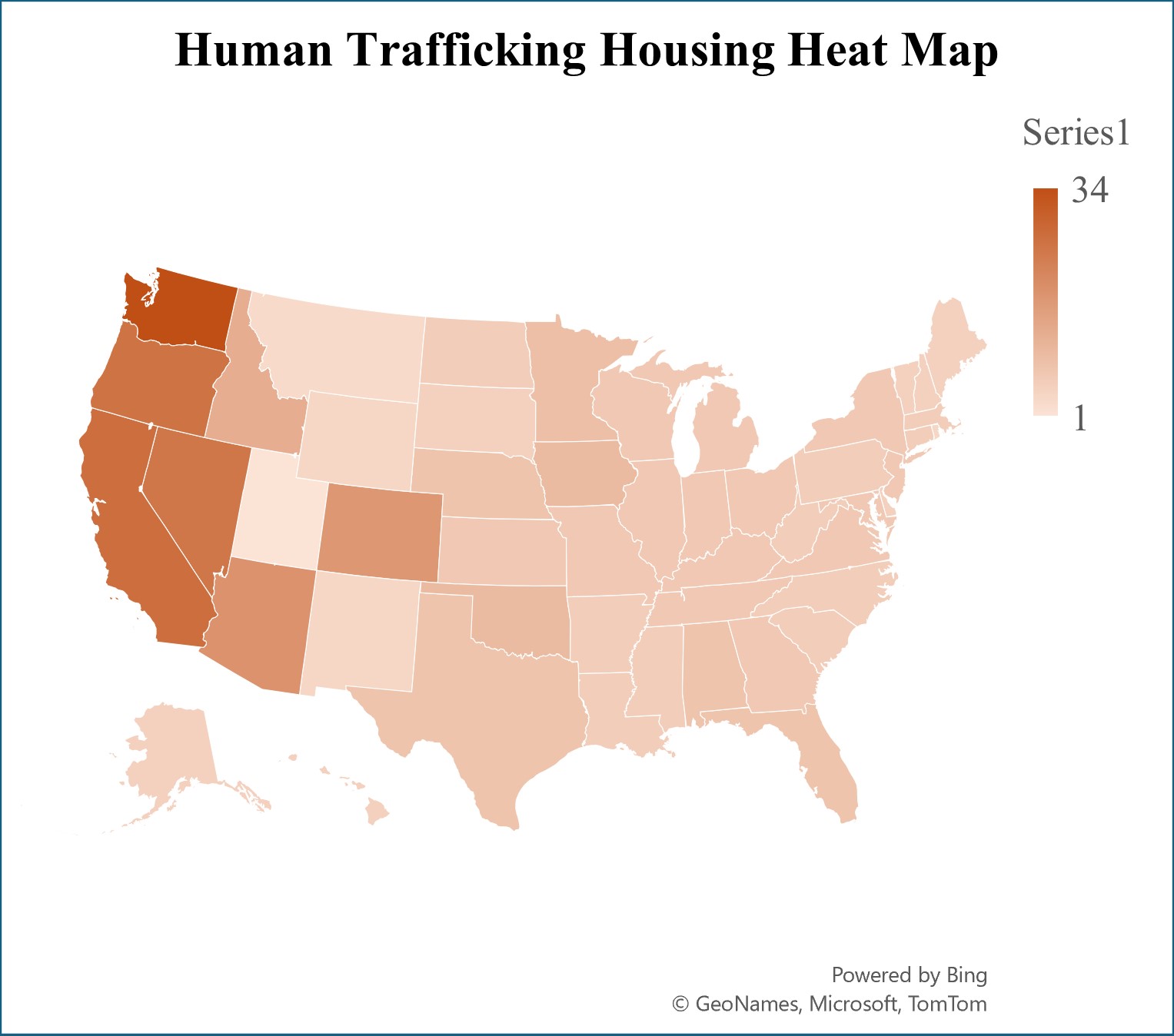

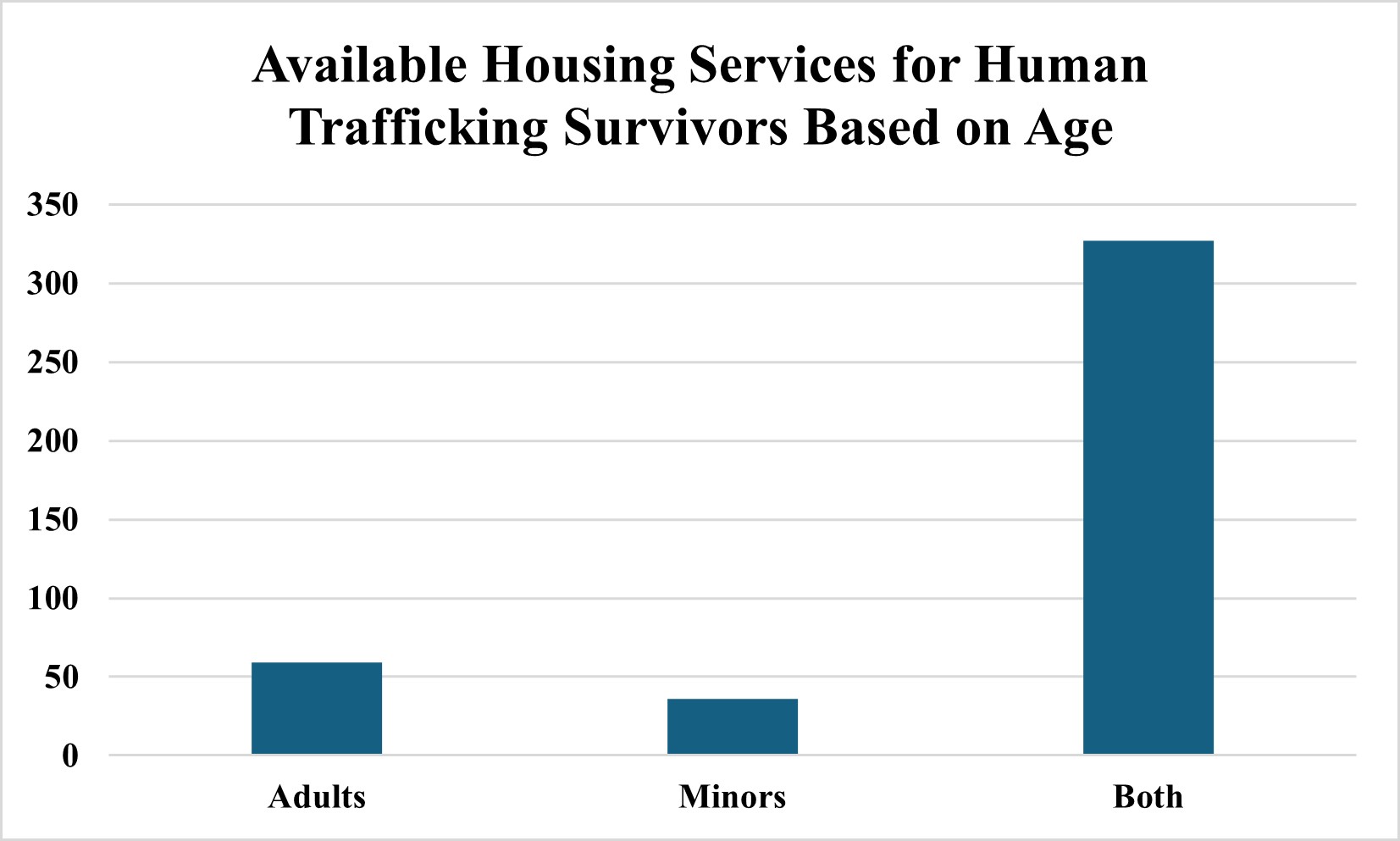

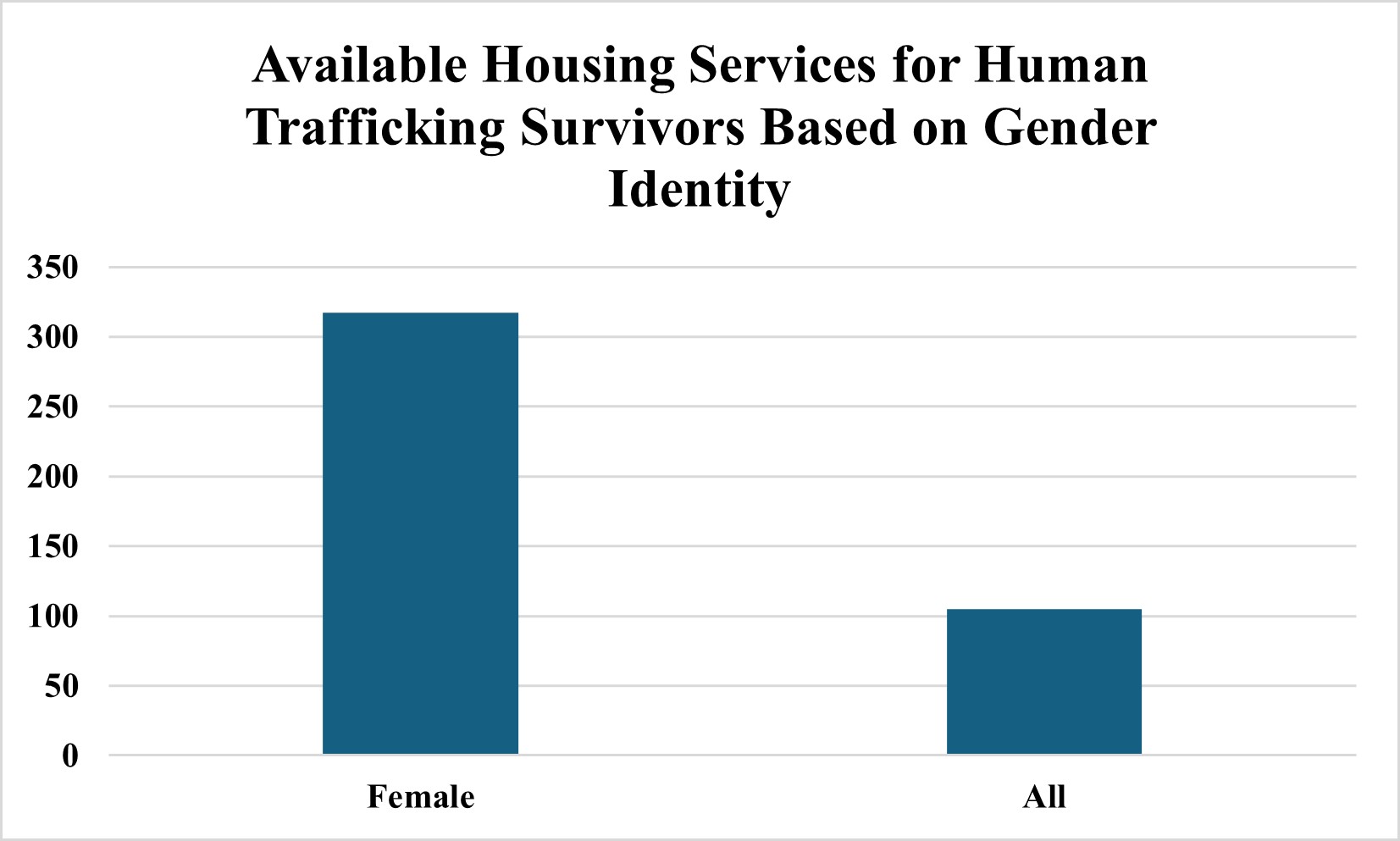

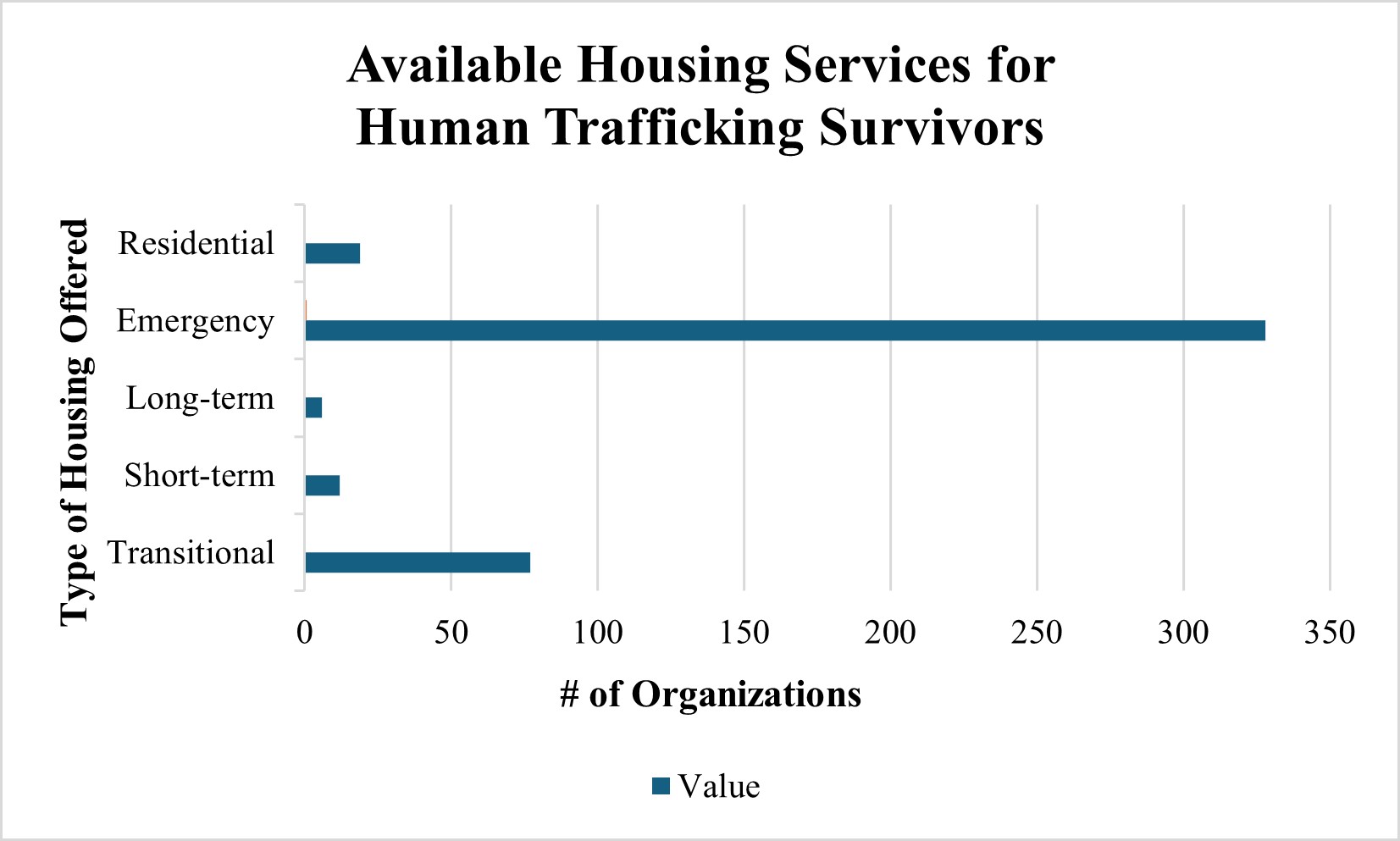

Human trafficking involves the use of force, fraud, or coercion to obtain some type of labor or commercial sex act. Every year, millions of women, children, and men are trafficked worldwide. When survivors enter a recovery and reintegration process, housing is a top priority for these individuals. Unfortunately, little is known about the effectiveness of current housing services and how they affect survivors. The purpose of this mixed-methods study is to identify the most effective practices for housing survivors of human trafficking in the U.S. The first step of the research was stakeholder mapping, which helped identify organizations across the United States that offer housing for survivors. This involved searching through each state to find organizations that provided housing to human trafficking survivors. We identified 422 organizations through various search engines, including Google, Bing, and Yahoo. Then, a “heat map” was created to show the saturation of housing services throughout different states. This showed that the western coast (Washington, Oregon, California, Nevada) had much higher saturation than the rest of the country. Utah was the least saturated in the U.S. with only one organization offering housing for human trafficking survivors. Of the screened housing organizations, 74.21% offered emergency housing, 18.20% provided transitional housing, 4.50% offered residential housing, 2.71% offered short-term housing, and 1.36% provided long-term housing. This research is crucial for researchers and organizations to implement strategies that will help survivors of human trafficking. While long-term housing is the least common form of housing offered in this sample, the literature suggests that long-term housing is the most successful type of housing for human trafficking survivors. Future research is needed on causal factors related to housing programming availability, as well as the effectiveness of various housing types for human trafficking survivors.

Human Trafficking

Human Trafficking refers to “a crime that involves compelling or coercing a person to provide labor or services, or to engage in commercial sex acts” (UDJ, 2023). In addition to this, the exploitation of a minor for commercial sex is also human trafficking. There are different types of human trafficking, including sex trafficking and labor trafficking. Additionally, victims of human trafficking can be anyone, “regardless of race, color, national origin, disability, religion, age, gender, sexual orientation, gender identity, socioeconomic status, education level, or citizenship status” (UDJ, 2023). There are several consequences of human trafficking. Several studies showed that “depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder

(PTSD), and self-harm and attempted suicide are common among survivors in contact with refuge services” (Altun, 2017). When it comes to survivors in the context of human trafficking, housing is a big aspect. We want survivors to be in a safe environment, where they are less susceptible to being pulled back into the human trafficking environment.

Housing is a basic human need, as it allows us to have a place for us to feel comfortable and safe. Unfortunately, housing for human trafficking survivors is scarce and often has a complicated process that can take weeks before they can get into a type of housing. The purpose and scope of this review will be to look at housing within the context of human trafficking survivors.

The objectives of the literature review are to 1) look at the prevalence and patterns of how housing for human trafficking survivors has affected the likelihood of them being safe, 2) the risk factors for trafficking related to housing, 3) look at housing as a protective factor for human trafficking survivors, 4) reviewing interventions and housing programs for survivors to determine the effectiveness, 5) what gaps there are in the literature today and what needs to be furthered studied, and 6) looking at future directions for those involved in research surrounding housing for human trafficking survivors.

Prevalence and Patterns

When looking at human trafficking survivors, it’s important to have an overview and an understanding of how much this affects our societies. Globally, “the most common form of human trafficking (79%) is sexual exploitation. The victims of sexual exploitation are predominantly women and girls. Surprisingly, in 30% of the countries that provided information on the gender of traffickers, women make up the largest proportion of traffickers. In some parts of the world, women trafficking women is the norm.” (UN, 2009).

Additionally, from 2008 to 2019, the number of human trafficking victims went from 30,000 to 120,000. That is quadrupled, and since human trafficking is done in secrecy, it is impossible to know the entirety. When it comes to human trafficking victims, housing instability can play a big role in the likelihood that they will be pulled into that scene. An article states that “Traffickers are known to prey on the vulnerabilities of individuals that are experiencing poverty, homelessness, or are otherwise marginalized in society.” (UW, 2022). This shows that those who are not able to have a safe place to call their home can be more likely to be preyed on and attacked. They are constantly being exposed to others who might think that they are an easy target.

It’s known that homeless and runaway youth also experience the risk factors of trafficking at a higher rate. “LGBTQ+ youth are twice as likely to experience human trafficking as compared to their non-LGBTQ+ counterparts. This is due in part to many of these individuals being rejected by their families and facing higher rates of discrimination, violence, and economic instability.” (UW, 2022). We can see that there are several risk factors for all ages and it can be extremely hard to decrease that vulnerability. Additionally, those who are undocumented also face more risk factors for human trafficking, since they are afraid that someone who knows might tell law enforcement.

Risk Factors for Trafficking Related to Housing

When it comes to homelessness and trafficking, there is a clear connection. Housing insecurity and the lack of house stability are “major contributors to a vulnerability that can lead to exploitative situations” (Finger, 2023). Additionally, there are lots of studies that mention homeless youth having a high risk of being trafficked. In one study, they found that “among shelter youth, about half were living and sleeping on the streets, and half were experiencing unstable or temporary housing in the form of couch surfing, foster care, group homes, or a hotel” (Finger, 2023). This can show how dangerous it can be for youth who are homeless.

In another study, research found that “an estimated 4.2 million young people (ages 13-25) experience homelessness annually, including 700,000 unaccompanied minor youth ages 13 to 17” (Bardine, 2024). There is a lack of both adequate and stable housing for youth. When searching for housing, these youth might not be able to afford it and provide enough evidence and/or documentation as to why they need stable housing. Furthermore, migrant and refugee housing conditions are also struggling to keep individuals safe and away from exploitative situations. Usually, people forced to flee their homes and/or countries are migrating to dangerous territories.

One study found that “people fleeing conflicts, emergencies, and poverty are pushed to migrate in unsafe and vulnerable conditions…They could be exploited and trafficked during their journey, or at the destination, because of their social vulnerability” (Giammarinaro, 2023). Those who are migrating might also not have citizenship and enter areas illegally, and that can be held against them. There might be complications with language, as those who do not speak the primary language are also vulnerable to trafficking. This can be because they might not be able to get help from others, making them easy prey.

When searching for housing, they might face challenges due to these reasons. They might not be able to find housing using the appropriate tools and with the language barrier, it can make it harder to properly communicate what is needed at that point in time. Similarly to homeless youth, migrants might face challenges with providing identification and affording where they want to stay.

Housing as a Protective Factor

When thinking about stable housing in prevention, we must acknowledge that housing is a basic need. It is something all individuals need so they can feel safe and not become vulnerable to exploitative situations. There are several types of housing that a human trafficking survivor can choose from. The first is an emergency shelter. These are meant for crises. They provide immediate housing, but “only for a limited period and often in shared bedrooms with limited privacy.

While services provided by emergency shelters may meet the basic, immediate needs of individuals experiencing homelessness, they require the individual and service provider to begin working immediately to identify different longer-term housing solutions” (FNUSA,

2020). The next type is short-term and/or temporary housing. This is meant to help you if you need to stay somewhere for a few days or weeks.

Depending on the state, some of these can be specific to human trafficking survivors. Similar to temporary housing, there is also transitional housing. This can range anywhere from “six months to two years, allowing residents to build their savings and identify and secure permanent housing options. Often, transitional housing programs can be accessed through referrals from homeless or domestic violence shelters” (FNUSA, 2020). Additionally, there can be long-term shelters that can come in different forms, up to permanent supportive housing. All of these housing programs are designed to help individuals have a safe place to stay while they work with the program to determine where they will go when they leave to provide them the best chances of not becoming homeless again.

Interventions and Programs

There have been several studies that have looked at housing interventions, to analyze what the best strategies are. Looking at the housing needs of survivors is crucial for researchers and scientists to help in the ways they need. We can see that “Whereas the primary barrier to housing access is scarcity, housing resources dedicated to survivors is the best way to ensure availability and accessibility of housing for survivors. This dedicated funding can take many shapes, including grants, set-asides, preferences, or sponsor-based housing assistance” (DHUD, 2024). While housing programs specifically dedicated to human trafficking victims are rare, those are the most successful. Another successful housing intervention mentioned was providing long-term housing, whether it’s considered a shelter or an apartment that they lease. Several programs have tried this model in different areas with different focuses that have become quite successful. Long-term housing can be difficult for several programs due to the amount of funding that has to be put into the shelter.

There is also a demand for staffed shelters, which can be difficult. Nevertheless, the few housing shelters that have been able to provide long-term housing have seen a decrease in those individuals being put back into exploitative situations. It offers an opportunity for survivors to access housing quickly. When looking at youth-specific approaches, we see that offering group residential homes is successful. It creates a safe space in which youth can heal and slowly reintegrate into society. They are surrounded by others their age while they can receive the unique needs that are needed by youth survivors.

Gaps in the Literature

Human trafficking research has not been a heavily researched area, which can create large gaps in the literature. One under-researched area is on the topics of adults. There is a lot of research surrounding youth risk factors, homelessness, and prevention. However, there has not been a focus on adults. It directly impedes anti-trafficking organizations from providing what adults need. Additionally, there is almost no research on prevention for adult survivors. Another under-research area is geographical. There is a large amount of research in the western part of the US, but almost no research in any other part of the US. Furthermore, it is rare to find studies done in other parts of the world, especially in Africa.

Another issue can be found in the lack of research on the effectiveness of aftercare services. There is research on how to reach out and get resources out to survivors, which is great. However, we don’t have enough research to know how effective these resources are and if they are helping or harming survivors. Some aftercare services that are lacking in research can include housing programs, reintegration programs, therapy, etc.

There are also methodological limitations when it comes to gaps in the literature. The first is issues with reporting. We know that not everyone decides to report to law enforcement, and those who do report might not clarify the number of times or the amount of people. This can create gaps as we are not sure how many people are in human trafficking situations to any degree. Additionally, there are issues with data collection. There are several ways that a research team can conduct a survey and analyze outcomes, which means that data collection can be biased and inaccurate.

Future Directions

As we look toward the future, several recommendations are crucial for researchers to take in order to help anti-trafficking organizations. The first is to focus on what they are needing, not what we think they need. For instance, national statistics on trafficking show that “a substantially larger number of individuals reach out to services like the Trafficking Hotline than are identified by active law enforcement interventions. These data suggest that outreach, even without direct intervention and screening, in the form of increased visibility and accessibility of resources for survivors, can have clear benefits” (DHUD, 2024). We can see that individuals are more likely to reach out to hotlines rather than housing programs.

This can help service providers get into contact with these hotlines to provide their information so it can be passed down. Researchers can conduct studies to assess the effectiveness of this practice. Another recommendation would be to conduct more research in the aftercare process. As was mentioned before, there is almost no research done in that area. We must understand how survivors cope with the situation afterward and how to best help them. This can also be a way for researchers to look at what survivors usually think, do, and feel after these events have occurred.

Getting information about what they need from the survivors themselves can increase the gap in the literature that we have about what the survivors’ conceptualization is. Doing more research on what type of housing programs are the most effective, for each age range can also be extremely helpful so new organizations can focus on those areas that might have been neglected. Lastly, looking at the possible connection between childhood abuse and trauma is necessary as prior studies “have linked childhood abuse to vulnerability to trafficking, especially among children. However, more studies that examine the dynamics of these relationships – such as the potential causal pathways – are needed, so that future efforts can be directed on where, when, and how to intervene” (Le, 2019). All of these recommendations can fill those gaps in the literature, ultimately leading us to be able to help more survivors through their healing process.

Bibliography

Altun, S., Abas, M., Zimmerman, C., Howard, L. M., & Oram, S. (2017). Mental health and human trafficking: Responding to survivors’ needs. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5618827/

Bardine, D. (2024). The intersection between youth homelessness and human trafficking. Retrieved from https://humantraffickingsearch.org/the-intersection-between-youth-homelessness-and-human-trafficking/

Beatty, J., & Wagner, A. (2021). Retrieved from https://www.banking.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Trafficking%20Survivors%20Housing%20Act%20One-Pager.pdf

Clawson, H., Dutch, N., Salomon, A., & Grace, L. G. (2009). Study of HHS programs serving human trafficking victims. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/study- hhs-programs-serving-human-trafficking-victims

Clawson, H., Dutch, N., Solomon, A., & Grace, L. G. (2009). Human trafficking into and within the United States: A review of the literature. Retrieved from https://aspe.hhs.gov/reports/human-trafficking-within-united-states-review-literature-0

Cody, A., Matthew, R., Greenburg, L., Murphy, L., Harper, C., Swedo, E., … Leemis, R. (2020). Strategies for Runaway and Homeless Youth Settings. Retrieved from https://rhyclearinghouse.acf.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/document/acf_issuebrief_htprev ention_10202020_final_508.pdf

Court, C. (2017). Human trafficking in California. Retrieved from https://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/human-trafficking-toolkit-cfcc.pdf

Davy, D. (2016). (PDF) Anti-human trafficking interventions: How do we know if they work? Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/301720279_Anti-Human_Trafficking_Interventions_How_Do_We_Know_if_They_Are_Working

Domoney, J., Howard, L. M., Abas, M., Broadbent, M., & Oram, S. (2015). Mental Health Service Responses to human trafficking: A qualitative study of professionals’ experiences of providing care – BMC psychiatry. Retrieved from https://bmcpsychiatry.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12888-015-0679-3

Donohue-Dioh, J., Otis, M., Miller, J., Sossou, M.-A., delaTorres, C., & Lawson, T. (2020). Survivors’ conceptualizations of human trafficking prevention; an exploratory study. Retrieved from https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0149718920301774

DHUD. (2024). Housing needs of survivors of human trafficking study. Retrieved from https://www.huduser.gov/portal/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Housing-Needs-of-Survivors-of-Human-Trafficking-Study.pdf

Dyvik, E. H. (3AD). Human trafficking – Statistics & Facts. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/topics/4238/human-trafficking/

Finger, D. (2023). Housing insecurity and the persistent connection to human trafficking. Retrieved from https://combathumantrafficking.org/blog/housing-insecurity- trafficking/

FNUSA. (2020). HOUSING OPTIONS FOR SURVIVORS OF HUMAN TRAFFICKING. Retrieved from https://freedomnetworkusa.org/app/uploads/2020/07/Housing-Options- for-Survivors-of-Trafficking-Final.pdf

Giammarinaro, M. G. (2023). Human trafficking risks in the context of Migration. Retrieved from https://www.ohchr.org/en/stories/2016/09/human-trafficking-risks-context-migration

Grant, N., Galos, E., Bartolinii, L., & Cook, H. (2017). Migrant vulnerability to human trafficking and exploitation: Evidence from the Central and Eastern Mediterranean migration routes. Retrieved from https://publications.iom.int/books/migrant- vulnerability-human-trafficking-and-exploitation-evidence-central-and-eastern

Guarcello, L., Wong, L., & Macaveiu, C. (2023). ► Synthesis Review of Human Trafficking Studies from 2010 … Retrieved from https://rtaproject.org/wp- content/uploads/2023/07/RTA_HTEGM_Synthesis_Report_en.pdf

Hall, E. (2024). Supporting human trafficking survivors – A guide for housing providers. Retrieved from https://www.navigatehousing.com/human-trafficking-survivors/

Hemmings, S., Jakobowitz, S., Abas, M., Bick, D., Howard, L. M., Stanley, N., … Oram, S. (2016). Responding to the health needs of survivors of human trafficking: A systematic review – BMC health services research. Retrieved from https://bmchealthservres.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12913-016-1538-8

LCHT. (2023). Housing, homelessness, and human trafficking. Retrieved from https://combathumantrafficking.org/blog/homeless-trafficking/

Le, P. (2019). Human Trafficking Health Research: Progress and Future Directions. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6348385/

Macy, R. J., Eckhardt, A., Wretman, C. J., Hu, R., Kim, J., Wang, X., & Bombeeck, C. (2024). Developing Evaluation Approaches for an Anti-Human Trafficking Housing Program. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328039672_httpjournalssagepubcomdoiabs1011770887302X07303626

OVC. (2024). Meeting the housing needs of survivors of human trafficking. Retrieved https://www.huduser.gov/portal/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Housing-Needs-of-Survivors-of-Human-Trafficking-Study.pdf

Preble, K., Nichols, A., & Cox, A. (2022). Working With Survivors of Human Trafficking: Results From a Needs Assessment in a Midwestern State, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328039672_httpjournalssagepubcomdoiabs1011770887302X07303626

Richards, D. (2022). The intersection between housing instability and human trafficking. Retrieved from https://humantraffickingsearch.org/resource/the- intersection-between-housing-instability-and-human-trafficking/

Schroder, E., Yu, H., Okech, D., Bolton, C., Aletraris, L., & Cody, A. (2023). Do Social Service Interventions for Human Trafficking Survivors Work? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328039672_httpjournalssagepubcomdoiabs1011770887302X07303626

Sprang, G., Stoklosa, H., & Greenbaum, J. (2022). The Public Health Response to Human Trafficking: A Look Back and a Step Forward. Retrieved from https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/00333549221085588

Talwar, S. (2023). Psychosocial interventions for survivors of human trafficking. Retrieved from https://www.nationalelfservice.net/populations-and-settings/vulnerable-people/survivors-of-human-trafficking/

Tiller, J., & Reynolds, S. (2020). Human trafficking in the emergency department: Improving our response to a vulnerable population. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7234705/

UNODC. (2016). Global report on trafficking in persons. Retrieved from https://www.unodc.org/documents/data-and- analysis/glotip/2016_Global_Report_on_Trafficking_in_Persons.pdf

USDJ. (2023). What is human trafficking? Retrieved from https://www.justice.gov/humantrafficking/what-is-human-trafficking

Yousaf, F. (2017). Forced migration, human trafficking, and human security. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/328039672_httpjournalssagepubcomdoiabs1011770887302X07303626

Media Attributions

- 137489262_image1

- 146879582_image2

- 146879585_image3

- 146881378_image4