12 Interprofessional Communication and Collaboration

Laura K. Garner-Jones

Chapter 12 Overview

- Review professional communication and essential elements

- Define interprofessional communication

- Understand factors that influence and resources that promote interprofessional communication

- Discuss the importance, benefits, barriers, and promoters of Interprofessional Collaborative Practice (IPCP)

- Apply elements of the TeamStepps evidence-based framework

Introduction

Professional communication is defined as the interaction between healthcare professionals, with the primary goal of achieving positive health-related outcomes (Street & Mazor, 2017). When successful communication practices become a central component of an organization, it can transform healthcare delivery. Safe and efficient care involves the coordinated activities of multiple teams of healthcare professionals. For example, while one team may focus on treating an underlying condition, other teams may address other health needs. Still, other teams may support the patient’s broader care needs, including those provided in non-hospital care settings. A team consists of two or more people who interact dynamically, interdependently, and adaptively toward a common and valued goal, and have specific roles or functions.

Professional Communication

Professional communication is vital in healthcare. Communication is essential to any successful working relationship, and collaborative working relationships are integral to the healthcare industry. Nurses work with people from different professions, classes, statuses, careers, and vocations. To communicate respectfully with colleagues, nurses should utilize the following elements (Table 12.1).

Table 12.1 – Effective Professional Communication Elements

| Element | Description |

| Assertiveness | Showing confidence in oneself is assertiveness. Nurses who are assertive are more likely to build effective communication among healthcare team members. Some facilities offer assertiveness training for nurses, recognizing that assertive nurses can improve patient care (Nakamura et al., 2017).

An assertive nurse also advocates for patients until their concern is addressed. Assertive nurses are a necessity for patients who are unconscious, nonverbal, or have no advocate at their side, as they must speak up as the voice of the patient. Using assertive communication is also an effective way to resolve problems with clients, coworkers, and healthcare team members. |

|---|---|

| Courtesy | Being courteous in healthcare communication is vital. Courtesy refers to the practice of being polite, respectful, and considerate when interacting with patients, their families, and colleagues. It involves using polite language and maintaining a friendly and professional demeanor. Initiation of the nurse-patient relationship depends on the nurse’s ability to begin with a pleasant greeting and friendly smile. These actions can build trust and place the patient at ease.

By maintaining qualities of politeness and friendliness, the nurse conveys continuous acceptance of the patient and interest in discussing the patient’s feelings and concerns. Nurses often encounter patients who are not courteous to them; however, nurses should always be courteous to their patients. Nurses who are courteous in all communication encounters are more likely to deliver safe and effective care to their patients (Sibiya, 2018). |

| Empathy | Empathy is the ability to recognize, understand, share, and validate feelings with another person. Empathy involves showing understanding of another’s situation or perspective and enables helping behaviors (Sussex Publishers, 2025). Communicating with empathy has also been described as providing “unconditional positive regard.”

Research has demonstrated that when health care teams communicate with empathy, there is improved client healing, reduced symptoms of depression, decreased medical errors (Morrison, 2019), improved patient outcomes and satisfaction (Babaii et al., 2021), and better engagement, compliance, and a more positive attitude toward recovery (Bas-Sarmiento et al., 2019). |

| Listening | The ability to thoughtfully receive and interpret messages is called listening. The listener should be able to restate what someone has said after the speaker has finished. Listening can be active or passive. When someone listens by giving their full attention, listening to understand, and providing thoughtful input, they are engaging in active listening; when someone listens to simply hear the messages being sent but may not be mentally or emotionally present and does not engage in the communication process, they are practicing passive listening.

Healthcare providers must be actively listening as patients provide them with information that helps them treat the patient safely and effectively. Nurses also need to recognize when a patient may not understand the messages received, even if the patient provided nonverbal communication, such as a head nod, indicating they understood. For example, when the patient is asked to repeat the instructions they received, the nurse may find discrepancies. The nurse needs to ensure the listener understands, preventing discrepancies regarding the patient’s medical care. |

| Resolution | In health care, resolution often refers to the communication used when addressing adverse events or risk management concerns. Resolution also involves reaching a point where both parties involved in the communication feel satisfied and understood, and that their objectives have been achieved. Effective resolution contributes to clear understanding, improved relationships, and the achievement of desired goals.

Adverse events and risk management concerns occur when something has gone wrong. An adverse event could be a medication error or the unintentional death of a patient. Resolution includes healthcare providers discussing through clear and structured communication what went wrong and how to prevent adverse events from occurring again. |

| Trustworthiness | Nursing has been considered the most trusted profession since the 1990s, when the Gallup poll on most trusted professions was first conducted (Gaines, 2023). Nurses are considered honest in their words and actions. They are trusted to deliver honest care with compassion, providing education and answering questions with patience. Ensure that you are honest and trustworthy in all you do and say, both with patients and colleagues. |

| Understanding | Communication is most effective if all messages received are understood. Patients are more likely to follow directions provided during an educational session if the information is supplied in a way the patient readily understands. If the patient receives the communication in multiple forms, such as verbal, written, and electronic, they will likely better understand the message. A patient who does not understand the directions given to them is less likely to obtain positive health outcomes. |

| Use of Names and Titles | Nurses should respect the professionals that they work with on the healthcare team and use their correct name and title. Nurses should also ask patients what they prefer to be called—their name, title, and pronouns; doing so helps establish a positive patient-provider relationship. |

Interprofessional Communication

Interprofessional communication refers to the exchange of information among members of the patient care team, including individuals from various professions. For example, it may involve you as the nurse, patients, their families, and other healthcare professionals, such as physicians, pharmacists, dietitians, and social workers.

Teams with strong communication and leadership skills typically achieve superior outcomes, reduce stress levels, and derive greater satisfaction from their work and relationships with peers, as well as with patients and their families or caregivers. Interprofessional communication encompasses verbal, written, and nonverbal communication, as defined in Chapter 8.

-

- During interprofessional communication, verbal communication may include conversations between two or more members of the interprofessional team, usually in person or over the telephone (See Table 12.2).

- Written communication in the interprofessional context commonly includes documentation notes in a patient’s chart, such as progress notes, physician orders, medication administration records, diagnostic reports, referral letters, and discharge notes. Other examples may include emails and, more recently, texts.

- Non-verbal communication in the interprofessional context involves conveying meaning and interpretation through body language, including facial expressions, eye contact, body position, and gestures. It is important to be aware of your body language and ensure that it aligns with your verbal language.

Table 12.2 – Examples of Interprofessional Communication

|

Communication type |

Verbal communication example |

|---|---|

|

Client/unit rounds: Interprofessional group discusses the client’s status and plan of care; typically, the patient and family are involved in these rounds. |

Nurse: “Mr. Molina’s blood pressure has been stabilized all night with no chest pain since 2330. He remains on a saline drip and is scheduled for a cardiac catheterization this morning.” Physician: “What’s his cognitive and renal status like?” Nurse: “He is alert and oriented. No renal issues. He was started on an oral beta blocker last night and received a dose this morning. Additionally, he was given a dose of 20 mg furosemide this morning. However, he is wondering about whether he should restart his cholesterol medication.” Physician: “Yes, that is fine to restart, and please notify me when his cath results come back.” Nurse: “Sounds good.” |

|

In-person or phone conversations: The nurse is providing a client update and consulting with another healthcare professional on a plan of action. |

Nurse: “Hello, I am Rita Lin, a registered nurse working with the client Meaka Lorne at General High School. Meaka is having suicidal ideation, although she does not have an immediate plan. However, I think it is time to initiate more intensive therapy.” Mental Health Therapist: “Yes, I remember Meaka. How is her anxiety and depression?” Nurse: “Her anxiety has been exacerbated over the last couple of weeks, and as a result, she hasn’t been going to school. She has felt quite sad and gloomy over the last week, which is when the thoughts of suicide emerged.” Mental Health Therapist: “I recall this is how it began last year.” Nurse: “Yes, she also indicated that.” Mental Health Therapist: “Can you remind me whether she still lives with her father?” Nurse: “Yes, she does, and he is with her at home right now.” Mental Health Therapist: “Okay, I will get her in for an appointment.” |

|

Discussions: Occur among healthcare professionals while providing patient care. |

Physician: “I am just about to insert the central venous catheter, could you shift the light a little this way.” Nurse: “Yes, no problem. I have the IV primed, just let me know when you want me to hand it to you.” Physician: “Will do…Ms. Bykov, you will feel a slight pinch, please try and hold as still as you can.” Patient: “Okay.” |

Factors Influencing Interprofessional Communication

Several factors can influence interprofessional communication in either positive or negative ways, and thus have either positive or negative effects on healthcare professionals and client outcomes. The factors affecting interprofessional communication can be divided into three main categories: those related to the physical environment, those related to the context, and those related to the communication styles of the people involved.

-

- Physical: You will often be working in physical environments that are sometimes noisy and have many moving parts, including patients, families, and multiple members of interprofessional teams. In addition to the many people, there may be beeping machines and overhead announcements. You should be aware that this can cause sensory overload.

- Context: Interprofessional communication in healthcare environments occurs within a complex context that involves a high volume of information and dynamic, complex clinical situations, requiring a high level of acuity. It can be very intense, with life-threatening conditions, death, uncertainty, fear, and anxiety, which can lead to work overload. This context can also influence the dynamic nature and intensity of interprofessional conversations. The hierarchical relationships that exist within interprofessional teams, as well as imbalances of power or perceptions of power, can also influence how individuals communicate and interpret conversations.

- Styles: Each group of healthcare professionals has its own communication style, which may not align with those of other healthcare professionals. For example, nurses are often taught to be descriptive and embed narrative elements in their communication. This descriptive style capitalizes on a comprehensive and storied approach. Other healthcare professionals, such as physicians and pharmacists, are taught to be more concise and efficient in their communication. As you can imagine, these two communication styles may not always align, so it is essential to reflect on how to tailor your communication to the person or group you are speaking with, while still conveying your point of view as a nurse.

Because these factors can impact the quality and effectiveness of communication among healthcare professionals, it is essential to identify common challenges and explore practical strategies to address them. Table 12.3 presents examples of ineffective interprofessional communication and strategies to manage each one.

Table 12.3: Ineffective Interprofessional Communication and Effective Strategies

|

Example |

Effects |

How to Manage This Type of Communication |

|---|---|---|

|

Disrespectful Communication: Physical Therapist: “It’s 11 am already!” [shakes head in disapproval] “Goodness gracious, you haven’t got her out of bed yet?! What’s wrong with you?”

|

Demoralizes and demeans another person. Although there may be a reason why the patient was not helped out of bed, the nurse may feel disempowered and not share the information.

|

The nurse could respond by saying: “It is probably better for you to inquire about the reasons that I have not gotten the client out of bed. Your communication is disrespectful and disregards the current situation with Mrs. Hart. Would you like to know what is going on?”Alternatively, the physical therapist, who was initially disrespectful, could have engaged in a discussion that is guided by inquiry instead of blame, and said: “I noticed Mrs. Hart is not out of bed yet. How can I help?” |

|

Failure to Communicate Concern: Nurse: “The client’s BP is 140/88.” Physician: “Okay.”

|

The nurse stated a finding, but did not indicate or emphasize their concern. Thus, the physician did not recognize the need to be concerned or engage in a dialogue. Failure to communicate one’s concern can have a negative effect on patient outcomes. |

When communicating, it is essential to express your concerns and ensure that the individual you are discussing them with understands the importance of what you are saying.For example, the conversation could be modified such that the concern is acknowledged, and they engage in a discussion about the plan of care:

Nurse: “The client’s BP is 140/88. This is out of the ordinary for this patient; their baseline BP is 100/60. I have a serious concern about the high BP, and I think we should intervene.” Physician: “That is quite a jump. Is the client’s pain well-controlled?” |

|

Failure to Communicate the Rationale for an Action or Decision: Nurse: “Let’s try putting the client in the prone position.” Patient Care Technician: “You want us to roll the client onto their abdomen.” Nurse: “Yes.” Patient Care Technician: “I think that will be difficult.”

|

Neither of these professionals provides a rationale for their action or decision. As a result, neither professional understands the other’s perspective. |

When communicating, it is important to provide a rationale for your actions and decisions.For example, the conversation could be modified so that a person’s rationale is clearly identified, as such:

Nurse: “Let’s try putting the patient in the prone position. Some recent research has suggested that this can improve respiratory function when a client has severe respiratory distress that is not responding to other interventions.” Patient Care Technician: “I am concerned about rolling the client onto their abdomen with all of the tubes and wires. Do you have any suggestions?” Nurse: “If you are open to it, I can grab one more person and we can do it as a team. What do you think?” |

|

Unclear and/or Incomplete Communication or Miscommunication: Charge Nurse: “Can you help Ms. Di Lallo with her breakfast?” Patient Care Technician: “Yes” Charge Nurse: “She’s at table 1.” Patient Care Technician: [walks over to the patient], “Hi, Ms. Di Lallo, are you ready for your breakfast?” Patient: “Yes, can you please pass me my coffee?” Patient Care Technician: [passes Ms. Di Lallo her coffee]. Charge Nurse: “Oh, hold on! I forgot to mention, Ms. Di Lallo, we need to thicken your coffee first.” |

This unclear communication about the client’s diet led to a near miss. Miscommunication and/or unclear or incomplete communication can result in errors related to patient care, which can have serious consequences for their health. |

When communicating, it is essential to include all pertinent information to ensure safe and effective care. All healthcare professionals need to clarify any communication shared.For example, the conversation could be modified by ensuring that all required information is communicated:

Charge Nurse: “Can you help Ms. Di Lallo with her breakfast?” Patient Care Technician: “Yes” Charge Nurse: “Great, she’s at table 1. Ms. Di Lallo has dysphagia, so you need to make sure all her fluids are thickened and follow the dysphagia diet protocol. The thickener should be on her tray. Do you have any questions?” Patient Care Technician: “No, I’m aware of the dysphagia diet protocol and will monitor Ms. Di Lallo during her meal.” |

|

Ineffective Conflict Resolution on a Plan of Care: Nurse: “Mr. Pink said he does not feel he is ready to be discharged, and I agree.” Respiratory Therapy: “I think I’m able to determine when Mr. Pink can be discharged, considering I’ve been working with him for 6 months, and you just met him last week.” Nurse: “I think we need to talk to the whole team.” |

The communication is ineffective because healthcare providers disagree about the patient’s plan of care. They are not focusing on the context of the interprofessional communication and/or explaining their reasoning based on the client’s needs. They are focusing on their own opinions instead of using a person-centred perspective and evidence-informed approach.

|

In the event of a disagreement, healthcare providers must effectively explain their reasons within the context of person-centred care and evidence-informed approaches. It’s always important to use effective conflict resolution strategies.For example, the conversation could be modified as:

Nurse: “Mr. Pink said he does not feel he is ready to be discharged. I agree with him because he has no support system in place to help him with his activities of daily living at home.” Respiratory: “I believe he is physically ready to go home, but you bring up a good point. Let’s put together a plan for home care.” Nurse: “Great.” |

Resources to Facilitate Interprofessional Communication

Numerous resources are available to facilitate interprofessional collaboration and teamwork, including effective interprofessional communication. Ideally, all healthcare professionals, including nurses, would speak up for the sake of their patients. However, some healthcare professionals may struggle to voice their concerns and their perspectives. One objective of interprofessional communication tools is to provide structure and clarity, conveying succinct, comprehensive, and relevant information to other healthcare professionals, thereby improving patient care. Several standardized tools have been developed to facilitate interprofessional communication and prevent errors and miscommunication, including ISBAR and hand-off communication strategies.

SBAR

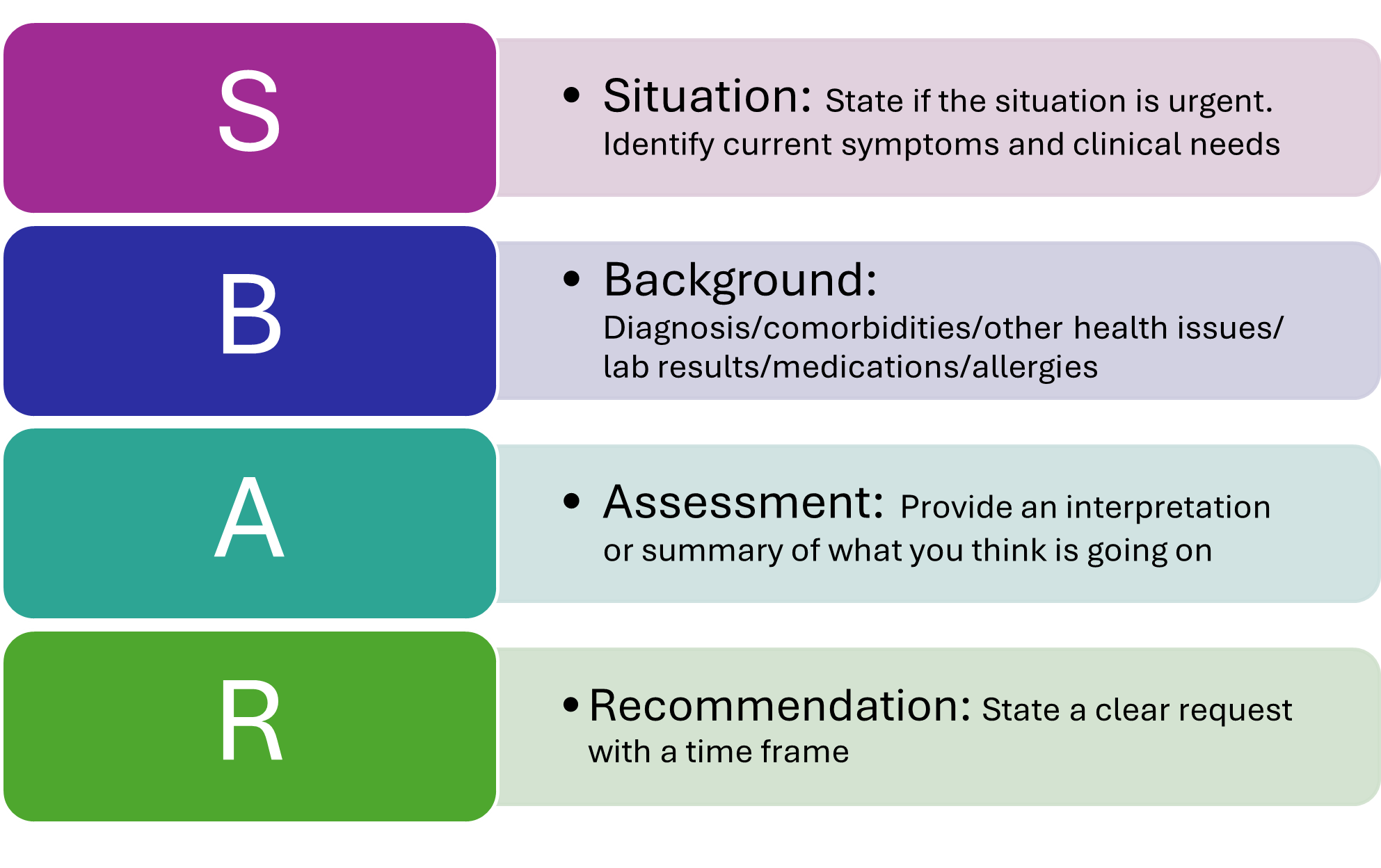

The SBAR tool is a common communication tool that facilitates effective verbal communication when discussing a client with another healthcare professional or during handover. It provides a framework so that communication is focused, concise, and complete. SBAR (Figure 12.1) is an acronym that stands for Situation, Background, Assessment, and Recommendation. It was first introduced by the U.S. military to facilitate communication (Jurns, 2019) and has since been adopted in the healthcare arena. The SBAR tool is particularly useful in urgent situations where immediate attention and action are crucial.

Figure 12.1 – SBAR Communication Tool

Research suggests that nurses do not consistently use all elements of ISBAR, with the sections on assessment and recommendation being particularly neglected (Spooner et al., 2016). It is essential to reflect on how you communicate and identify areas for improvement through the comprehensive use of tools.

Watch this video for an example of ISBAR to guide communication between two nurses.

Hand-Off Communication

Hand-off communication has been found to be a contributing factor to adverse events (Scott et al., 2017), wrong-site surgery, delay in treatment, falls, and medication errors (CRICO Strategies, 2015). Hand-off is defined as “a transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real- time process of passing patient- specific information from one caregiver to another or from one team of caregivers to another for the purpose of ensuring the continuity and safety of the patient’s care” (JCTH, 2020b, para. 2). the JCTH (2020b) has identified an average of 4000 hand-offs each day in a typical teaching hospital. The opportunity for inadequate communication is vast.

Various types of nursing shift-to-shift handoff reports have been employed over the years. Evidence strongly supports the notion that bedside handoff reports enhance patient safety and satisfaction, as well as improve patient care, by effectively communicating current, accurate client information in real-time (Dorvil, 2018). The JCTH (2020a) developed the Targeted Solutions Tool (TST) to enhance hand-off communication. The TST provides a framework for improving the effectiveness of communication when a patient moves from one setting to another within the organization or to the community. The TST has the following benefits:

-

- Increased patient, family, and staff satisfaction

- Successful patient transfers without “bounce back” (patients returning to the previous unit)

- Improved safety (JCTH, 2020a)

Benjamin et al. (2016) implemented the TST in the Emergency Department to determine the rate of defective handoffs (a TST concept) and the factors that contributed to the handoff. Prior to implementing the TST, the defective handoff rate was 29.9% (32 defective handoffs out of 107 handoffs). After the implementation of the TST, the defective handoff rate decreased by 58% to 12.5% (13 defective handoffs out of 104 handoffs). As the defective handoff rate decreased, the number of adverse events also decreased.

Bedside reports typically occur in hospitals and include the client, along with the outgoing and the incoming nurses, in a face-to-face handoff report conducted at the client’s bedside. HIPAA rules must be considered when visitors are present or when the room is not a private one. Family members may be included with the client’s permission. Although a bedside handoff report is similar to an ISBARR report, it contains additional information to ensure continuity of care across nursing shifts. For example, the “assessment” portion of the bedside handoff report includes detailed pertinent data the oncoming nurse needs to know, such as current head-to-toe assessment findings to establish a baseline; information about equipment such as IVs, catheters, and drainage tubes; and recent changes in medications, lab results, diagnostic tests, and treatments. You can review and print a copy of the AHRQ Bedside Shift Report Checklist.

Watch this video for an example of Bedside Shift Report

Interprofessional Collaboration and Collaborative Practice

Healthcare has faced numerous challenges in delivering quality care over the past 50 years. The population is older, more diverse, medically complex, with a higher prevalence of chronic disease requiring multiple specialty providers, a greater reliance on technology and innovation, and uncoordinated delivery systems. Collaborative practice can improve the delivery of care through a concerted effort from all members of the healthcare team and leaders throughout the organization. Interprofessional or interdisciplinary collaboration is an indispensable part of nursing practice. The American Nurses Association (as cited in ANA, 2021) defines collaboration as “working cooperatively with others, especially in joint intellectual efforts, in a way that includes collegial action and respectful dialogue” (p. 110).

Collaborative practice has been shown to reduce the incidence of complications and errors, decrease the length of stay, and lower mortality rates. Collaboration also leads to a reduction in conflict among staff and lower turnover rates. Additionally, collaborative practice strengthens health systems, improves family health, improves infectious disease, assists with humanitarian efforts, and improved response to epidemics and noncommunicable disease (World Health Organization [WHO], 2010).

Nurses and other healthcare professionals must collaborate to address challenges that hinder progress in improving safety and quality of care. The IOM (2015) states, “No single profession, working alone, can meet the complex needs of patients and communities. Nurses should continue to develop skills and competencies in leadership and innovation and collaborate with other professionals in health care delivery and health system redesign” (p. 3). All healthcare providers must be prepared to work collaboratively in clinical practice with a common goal of building a safer, more effective, and patient-centered healthcare system. “When multiple health workers from different professional backgrounds work together with patients, families, and communities to deliver the highest quality of care” (Green & Johnson, 2015; WHO, 2010), it is referred to as Interprofessional collaborative practice (IPCP).

Watch this TedX video about collaboration in healthcare.

Barriers and Promoters to Collaboration

Morgan et al. (2015) conducted a review of the literature examining the elements of interprofessional collaboration in primary care settings. The overarching element in achieving and sustaining effective interprofessional collaboration was the opportunity for frequent, informal communication among team members. Continuous sharing of information led to an interprofessional collaborative practice, where knowledge is shared and created among team members, resulting in the development of shared goals and joint decision-making. Two key facilitators of interprofessional collaboration are the availability of a joint meeting time for communication and having adequate physical space.

Collaboration among healthcare professionals also requires leadership and planning, common goals, and a “teamwork” atmosphere. The literature discussed below reviews an assortment of promoters (actions that enhance collaboration and teamwork) and barriers that impact the success of collaboration. The main takeaways include a commitment to working together for a common goal, utilizing effective communication and collaboration skills, and taking the initiative to identify and resolve team conflicts.

Choi and Pak (2007) conducted a literature review to determine the promotors, barriers, and approaches to enhance interdisciplinary teamwork. The researchers discovered eight major concepts of teamwork and formulated them within the acronym “TEAMWORK” (See Table 12.3).

Table 12.3 – Promoting Behaviors and Barriers in “Teamwork”

|

|

Strategy |

Promoting Behaviors |

Barriers |

|---|---|---|---|

|

T |

Team |

|

|

|

E |

Enthusiasm |

|

|

|

A |

Accessibility |

|

|

|

M |

Motivation |

|

|

|

W |

Workplace |

|

|

|

O |

Objectives |

|

|

|

R |

Role |

|

|

|

K |

Kinship |

|

|

TeamSTEPPS

TeamSTEPPS® is an evidence-based framework used to optimize team performance across the healthcare system. It is a mnemonic standing for Team Strategies and Tools to Enhance Performance and Patient Safety. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, 2019), in collaboration with the Department of Defense, developed the TeamSTEPPS® framework as a national initiative to improve patient safety by improving teamwork skills and communication.

The TeamSTEPPS® model involves a series of training modules and integration of healthcare principles throughout all areas of the healthcare system (AHRQ, 2019). TeamSTEPPS® improves safety and the quality of care by:

-

- Producing highly effective medical teams that optimize the use of information, people, and resources.

- Increasing team awareness and clarifying team roles and responsibilities.

- Resolving conflicts and improving information sharing.

- Eliminating barriers to quality and safety (AHRQ, 2019, para. 2)

Watch this video for an Overview of TeamSTEPPS.

Communication

Communication is the first skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework. It is defined as a “verbal and nonverbal process by which information can be clearly and accurately exchanged among team members” (AHRQ, 2023). All team members should use these skills to ensure accurate interprofessional communication:

-

- Provide brief, clear, specific, and timely information to team members.

- Seek information from all available sources.

- Use check-backs to verify information that is communicated.

- Uses SBAR, call-outs, and handoff techniques (I-PASS) to communicate effectively with team members (AHRQ, 2023).

Leadership

Leadership is the second of the TeamSTEPPS framework’s skills. It is defined as the “ability to lead teams to maximize the effectiveness of team members by ensuring that team actions are understood, changes in information are shared, and team members have the necessary resources” (AHRQ, 2023). An example of a healthcare team leader in an inpatient setting is the charge nurse. Three major leadership tasks include sharing a plan, monitoring and modifying the plan as situations arise, and reviewing team performance. Tools to perform these tasks are discussed in the following subsections.

Sharing the Plan

Healthcare team leaders identify and articulate clear goals to the team at the start of the shift during inpatient care using a “brief.” The brief is a short session to start to share the plan, discuss team formation, assign roles and responsibilities, establish expectations and climate, and anticipate outcomes and likely contingencies (AHRQ, 2023)

Monitoring and Modifying the Plan

Throughout the shift, it is often necessary for the team leader to modify the initial plan as patient situations change in the unit. A “huddle” is an ad hoc meeting designed to ensure the continual progression of care toward the goal, re-establish situational awareness, reinforce the plan in place, or assess the need to augment or adjust it to optimize outcomes (AHRQ, 2023). Read more about situational awareness in the “Situation Monitoring” subsection below.

Reviewing the Team’s Performance

When a significant or emergent event occurs during a shift, such as a code, it is important to later review the team’s performance and reflect on lessons learned by holding a “debrief ” session. A debrief is a structured, yet informal and intentional, quick information exchange session designed to improve team performance and effectiveness through lessons learned and the reinforcement of positive behaviors (AHRQ, 2023).

Situation Monitoring

Situation monitoring is the third skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework and is defined as the “process of actively scanning and assessing situational elements to gain information or understanding, or to maintain awareness to support team functioning (AHRQ, 2023). Situation monitoring is an individual skill that refers to the process of continually scanning and assessing the situation to gain and maintain a clear understanding of what is happening around you. Situation awareness is an individual outcome that refers to a team member’s understanding of their surroundings, including the patient, other team members, the environment, and progress toward goals. The team leader creates a shared mental model (a team outcome) to ensure all team members have situation awareness and know what is going on as situations evolve. The STEP tool is used by team leaders to assist with situation monitoring (AHRQ, 2023).

STEP

The STEP tool is a situational monitoring tool used to understand what is happening with you, your patients, your team, and your environment. STEP stands for Status of the patient, Team members, Environment, and Progress toward the goal (AHRQ, 2023). As the STEP tool is implemented, the team leader continues to cross-monitor to reduce the incidence of errors. Cross-monitoring includes the following:

-

- Monitoring the actions and stress levels of other team members.

- Providing a safety net within the team.

- Ensuring that mistakes or oversights are caught quickly and easily.

- “Watching each other’s back” (AHRQ, 2023).

I’M SAFE Checklist

The I’M SAFE mnemonic is a tool used to assess one’s own safety status, as well as that of other team members, in their ability to provide safe patient care. I stands for illness, M for medication, S for stress, A for alcohol and drugs, F is for fatigue, and E is for eating and elimination. If a team member feels that their ability to provide safe care is diminished due to one of these factors, they should notify the charge nurse or other supervisor. Similarly, if a healthcare professional notices that another team member is impaired or providing care in an unsafe manner, it is an ethical imperative to protect clients and report their concerns in accordance with agency policy.

I’m Safe Checklist

- I: Illness

- M: Medication

- S: Stress

- A: Alcohol and Drugs

- F: Fatigue

- E: Eating and Elimination

(AHRQ, 2023).

Mutual Support

Mutual support is the fourth skill of the TeamSTEPPS® framework and is defined as the “ability to anticipate and support team members’ needs through accurate knowledge about their responsibilities and workload (AHRQ, 2023). Mutual support includes providing task assistance, giving formative feedback, and advocating for patient safety by using assertive statements to correct a safety concern. Managing conflict is also a component of supporting team members’ needs.

Task Assistance

Helping other team members with tasks builds a strong, trusting team. Task assistance includes the following components:

-

- Team members foster psychological safety and protect each other from work overload.

- Effective teams place all offers and requests for assistance in the context of patient safety.

- Team members foster a climate where it is expected that assistance will be actively sought and offered.

- Resilient teams are willing to ask for help and take responsibility for facing challenges and finding solutions.

- Assistance is sought from and provided to patients and family caregivers (AHRQ, 2023).

Formative Feedback

Formative is shared to improve team performance. Effective feedback should follow these parameters:

-

- Appreciative: Expresses gratitude and notes actions that team members do well.

- Timely: Given soon after the target behavior has occurred.

- Respectful: Focuses on behaviors rather than personal attributes.

- Specific: Relates to a specific task or behavior that requires correction or improvement.

- Directed towards improvement: Provides directions for future improvement.

- Considerate: Considers a team member’s feelings and delivers negative information with fairness and respect.

- Patient-focused: Addresses the impact of team behaviors on the patient’s well-being (AHRQ, 2023).

Advocating for Safety With Assertive Statements

When a team member perceives a potential patient safety concern, they should assertively communicate with the decision-maker to protect patient safety. This strategy applies to all team members, regardless of their position within the healthcare environment’s hierarchy. The message should be communicated to the decision-maker in a firm and respectful manner using the following steps:

-

- Make an opening.

- State the concern.

- State the problem (real or perceived).

- Offer a solution.

- Reach agreement on next steps (AHRQ, 2023).

Two-Challenge Rule

When an assertive statement is ignored by the decision-maker, the team member should assertively voice their concern at least two times to ensure that it has been heard by the decision-maker. This strategy is referred to as the two-challenge rule. When this rule is adopted as a policy by a healthcare organization, it empowers all team members to pause care if they suspect or discover a critical safety breach. The decision-maker being challenged is expected to acknowledge that they heard and understand your concern (AHRQ, 2023).

CUS Assertive Statements

During emergent situations, when stress levels are high or when situations are charged with emotion, the decision-maker may not “hear” the message being communicated, even when the two-challenge rule is implemented. It is helpful for agencies to establish clear and well-recognized guidelines, such as the two-challenge rule, that are universally understood by all staff. These assertive statements are referred to as the CUS mnemonic: “I am Concerned – I am Uncomfortable – This is a Safety issue!” (AHRQ, 2023).

Using these scripted messages may effectively catch the attention of the decision-maker. However, if the safety issue still isn’t addressed after the second statement or the use of “CUS” assertive statements, the team member should take a stronger course of action and utilize the agency’s chain of command. For the two-challenge rule and CUS assertive statements to be effective within an agency, administrators must support a culture of safety and emphasize the importance of these initiatives to promote patient safety.

Managing Conflict

Conflict is not uncommon on interprofessional teams, particularly when diverse perspectives from multiple staff members regarding patient care are present. Healthcare leaders must be prepared to manage conflict to support the needs of their team members. When conflict occurs, the DESC tool can be used to help resolve conflict by using “I statements.” DESC is a mnemonic that stands for the following:

- D: Describe the specific situation or behavior; provide concrete data.

- E: Express how the situation makes you feel/what your concerns are using “I” statements.

- S: Suggest other alternatives and seek agreement.

- C: Consequences should be stated in terms of impact on the patient and established team goals while striving for consensus (AHRQ, 2023).

The DESC tool should be implemented in a private area, focusing on what is right, not who is right.

Conclusion

Professional and interprofessional communication are foundational to safe, high-quality, and patient-centered care. Effective communication among healthcare professionals fosters collaboration, minimizes errors, and enhances trust and respect within the healthcare team. For nurses, mastery of communication elements such as assertiveness, courtesy, empathy, and active listening is essential not only for building therapeutic relationships with patients but also for advocating for their needs and coordinating care with other disciplines.

Interprofessional communication requires an understanding of different professional roles, communication styles, and contextual factors that may facilitate or hinder collaboration. Structured tools, such as ISBAR, TeamSTEPPS, and the Targeted Solutions Tool (TST), provide frameworks that standardize communication, promote clarity, and reduce adverse events. Collaborative practice, built upon mutual respect, shared goals, and open dialogue strengthens healthcare systems and leads to improved patient outcomes. By embracing evidence-based communication strategies and fostering a culture of teamwork and accountability, nurses contribute to a safer, more effective, and more compassionate healthcare environment.

References:

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2019). About TeamSTEPPS. http://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps/about-teamstepps/index.html

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. (2023, July). TeamSTEPPS 3.0 Curriculum Materials. https://www.ahrq.gov/teamstepps-program/curriculum/index.html

- American Nurses Association. (2021). Scope and standards of practice (4th ed.). https://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/scope-of-practice/

- Babaii, A., Mohammadi, E., & Sadoghiasl, A. (2021). The meaning of the empathetic nurse-patient communication: A qualitative study. Journal of Patient Experience, 8. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735211056432

- Bas-Sarmiento, P., Fernández-Gutiérrez, M., Díaz-Rodríguez, M., & iCARE Team. (2019). Teaching empathy to nursing students: A randomized controlled trial. Nurse Education Today, 80, 40–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2019.06.002

- Benjamin, M. F., Hargrave, S., & Nether, K. (2016). Using the Targeted Solutions Tool to improve emergency department handoffs in a community hospital. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 42(3), 107-118. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(16)42013-1

- Choi, B. C., & Pak, A. W. (2007). Multidisciplinarity, interdisciplinarity, and transdisciplinarity in health research, services, education and policy: 2. Promotors, barriers, and strategies of enhancement. Clinical & Investigative Medicine, 30(6), 224-232. http://doi.org/10.25011/cim.v30i6.2950

- CRICO Strategies. (2015). Malpractice risks of health care communication failures. https://www.rmf.harvard.edu/News-and-Blog/Newsletter-Home/News/2016/SPS-The-Malpractice-Risks-of-Health-Care-Communication-Failures

- .Dorvil, B. (2018). The secrets to successful nurse bedside shift report implementation and sustainability. Nursing Management, 49(6), 20-25. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NUMA.0000533770.12758.44

- Gaines, K. (2023). Nursing ranked as the most trusted profession for the 21st year in a row. nurse.org. https://nurse.org/articles/nursing-ranked-most-honest-profession/

- Green, B. N., & Johnson, C. D. (2015). Interprofessional collaboration in research, education, and clinical practice: Working together for a better future. Journal of Chiropractic Education, 29(1), 1-10. http://doi.org/10.7899/JCE-14-36

- Institute of Medicine. (2015). Assessing progress on the Institute of Medicine Report: The Future of Nursing. National Academies Press. https://nap.nationalacademies.org/catalog/21838/assessing-progress-on-the-institute-of-medicine-report-the-future-of-nursing

- Joint Commission for Transforming Healthcare. (2020a). Hand-off communications targeted solutions tool. https://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/what-we-offer/targeted-solutions-tool/hand-off-communications-tst

- Joint Commission for Transforming Healthcare. (2020b). Take 5: Tackling inadequate hand-off communication. https://www.centerfortransforminghealthcare.org/en/why-work-with-us/podcasts/take-5-tackling-inadequate-hand-off-communication/

- Jurns, C. (2019). Using SBAR to communicate with policymakers. Online Journal of Issues in Nursing, 24(1), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol24No01PPT47

- Morgan, S., Pullon, S., & McKinlay, E. (2015). Observation of interprofessional collaborative practice in primary care teams: An integrative literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 52(7), 1217–1230. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2015.03.008

- Nakamura, Y., Yoshinga, N., Tanoue, H., Nakamura, S., Aioshi, K., & Shiraishi, Y. (2017). Development and evaluation of a modified brief assertiveness training for nursing in the workplace: A single-group feasibility study. BMC Nursing, 16(29). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-017-0224-4

- Scott, A. M., Li, J., Oyewole-Eletu, S., Nguyen, H. Q., Gass, B., Hirschman, K. B., … & Project ACHIEVE Team. (2017). Understanding facilitators and barriers to care transitions: Insights from Project ACHIEVE site visits. The Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 43(9), 433-447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.02.012

- Spooner, A. J., Aitken, L. M., Corley, A., Fraser, J. F., & Chaboyer, W. (2016). Nursing team leader handover in the intensive care unit contains diverse and inconsistent content: An observational study. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 61, 165-172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2016.05.006

- Sibiya, M. N. (2018). Effective communication in nursing. InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.74995

- Street Jr, R. L., & Mazor, K. M. (2017). Clinician–patient communication measures: Drilling down into assumptions, approaches, and analyses. Patient education and counseling, 100(8), 1612-1618. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2017.03.021

- Sussex Publishers. (2025). Empathy. Psychology Today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/basics/empathy

- World Health Organization. (2010). Framework for action on interprofessional education & collaborative practice. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/framework-for-action-on-interprofessional-education-collaborative-practice

Media Attributions:

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (2017). Bedside shift report checklist. Licensed under a CC0. Retrieved at: https://www.ahrq.gov/patient-safety/patients-families/engagingfamilies/strategy3/index.html

- AHRQ Patient Safety (2019, Aoril 18) Bedside shift report: Patient and family engagement [Video] YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=22omJXNfWkM

- AHRQ Patient Safety. (2015). TeamSTEPPS overview [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p4n9xPRtSuU

- NCLEX Mastery. (2021, September 7). I-SBAR shift report handoff: Nurse to nurse demo [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uERVFUMo2Vo

- TEDx Talks. (2018). Collaboration in health care: The journey of an accidental expert? [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qOV-5h0FpAo

OER Resources Utilized in this Section:

- Belcik, K. (2022). Leadership and management of nursing care. Pressbooks: Texas State University. https://pressbooks.txst.edu/nursinglm/ Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E (2nd ed.). Open RN | WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC-BY) license.

- Lapum, J., St-Amant, O., Hughes, M., & Garmaise-Yee, J. (2020). Introduction to communication in nursing. Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.library.torontomu.ca/communicationnursing/ Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.

- Murphy, J. (2022). Transitions to professional nursing practice. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-delhi-professionalnursing/ Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

- Ochoa, D. (2022). NURS 3301 professional mobility. University of Texas: Rio Grande Valley. Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.utrgv.edu/nurs3301/ Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, except where otherwise noted.