Guidance and Lessons Learned

for Instructors Seeking to Add Video Creation to Their Skill Set

Wendy A. Swenson Roth, Ph.D.

Abstract

Videos have entered the classroom, whether for online asynchronous courses or as supplementary information in synchronous classes. COVID-19 accelerated the pace of online and video learning but left instructors with little time to explore the optimal use of this technology. Nonetheless, videos are here to stay, raising questions about what unique choices faculty must make when implementing them and what new skills are required as videos become additional content delivery sources. The following article provides implementation guidance and lessons learned for instructors seeking to add video creation to their skill set.

Keywords: video development, professional development, online teaching, scholarship of teaching and learning, video sources, hybrid, active learning

Introduction

There is little debate that video instruction is helping universities transition to online learning and increasing content availability, allowing students to learn anytime and anywhere. However, considering videos only as replacements for lectures or textbooks ignores the medium’s unique characteristics.

Videos fall in the continuum between a lecture’s flexibility and a textbook’s long shelf life. In addition to the intrinsic benefits of video in this online world, videos have longer shelf lives than face-to-face lectures and are more quickly adaptable than textbooks.

The following provides implementation guidance and lessons from a multiple-year process that converted a two-day-a-week, face-to-face lecture course into a hybrid flipped course with asynchronous video content. The process replaced one weekly in-class session with nearly 100 asynchronous videos and a second weekly session with in-class active learning exercises.

Much research exists on the importance of videos in the classroom and online. However, there is limited guidance on creating and implementing them, especially as a lecture replacement.

Video Sources:

When deciding to replace a lecture with video content, many interrelated decisions need to be made, such as the available resources, the team, and the completion date. These all closely align with the selection or creation of the video source.

When adding video content to the curriculum, new skills are often required. These skills can range from locating and curating videos developed by others to creating and editing videos alone or as part of a team. In addition, incorporating videos into the lecture space may require relinquishing some instructional control and, therefore, impacting the student relationship. Thus, determining the video source requires serious consideration.

The following describes video source categories, research, and items to consider when using a specific source.

1. Internet-available videos, such as YouTube, Ted Talks, Khan Academy or other sources

Using existing videos reduces or eliminates the need to create videos. Well before the surge in video content, professional documentary films and reality TV were incorporated into the classroom (Fee & Budde-Sung, 2014). Instructors have utilized numerous high-quality video sources in the classroom, including YouTube educational videos (Shoufan, 2019), Ted Talks (Loya & Klemm, 2016), and Khan Academy (Rueda-Gómez et al., 2023).

The ability to locate appropriate videos will vary with the uniqueness of the subject matter. Locating general content discussing the use of mathematical models may be easy. However, demonstrating a specific forecasting method may be more challenging.

These external sources come at a cost. Instead of creating the content, instructors must find videos that meet their requirements. Locating videos can be time-consuming and reduces the instructor’s ability to control the content provided to students compared to regular lectures. Professors become researchers looking for appropriate videos. Consideration of the motivation of the video creators and the accuracy of information is also required. In addition, since the instructor does not control the videos, an audit to ensure the video links continue to work each semester is essential.

2. Videos available with textbooks or from textbook providers

It has become commonplace for textbooks to include videos in a course. Some textbook providers now sell video libraries for specific courses. Researchers have successfully used videos developed by an educational publisher in their research (Tarchi et al., 2021). Instructors can utilize these videos in various ways, such as watching and discussing them in class. However, using these videos as lecture replacements may give away an amount of classroom control that many instructors would not be comfortable with; therefore, using these videos as additions and not replacements for the lecture.

3.Videos of lectures

Recording instructors’ lectures became commonplace during COVID-19, providing a quick and straightforward way to get course content on video. The recording often occurred in classroom lectures (D’Aquila et al., 2019). Some instructors have set up the recording to feel like a live classroom but record it without students, resulting in more control and flexibility during the recording process (Brecht & Ogilby, 2008). This video creation process results in a video with the feel of an actual classroom lecture but does not use the video medium’s unique advantages.

4. New videos produced by the professor in collaboration with university resources, including video production staff and instructional designers.

When deciding to produce new video content, each instructor must determine how much control they are willing to turn over to outside resources versus the time they are willing to spend learning a new skill. Producing new videos can be seen as spanning the continuum from high collaboration, relying on outside resources, to low collaboration, and learning video creation skills.

High Collaboration

High-production, high-collaboration videos are time-consuming and costly and are often seen in MOOCs (massive open online courses) where the volume of students can justify the expense. “Due to the importance of video content in MOOC’s video production, staff and instructional designers spend considerable time and money producing these videos” (Guo et al., 2014, p. 1).

The video production support provided at a university can vary widely. It can include guiding content development, storyboarding, scripting, recording, and editing. Universities often have staff, including instructional designers, to work with faculty on course design and video creation. As the demand for video content increases, these services are often in high demand, impacting on the timeline for implementation based on the availability of resources.

Though the instructor has more control over these created videos versus using videos from a textbook, they are still part of a team that must reach a consensus. Various types of conflict can result from collaborations between faculty and instructional designers, derailing the working relationship and impacting the results (Mueller, Richardson, Watson, & Watson, 2022). More specifically, this can include differing views on items such as types and styles of videos (You & Yang, 2021).

Low collaboration

Over their careers, instructors learn to use tools to improve their lectures, such as PowerPoint or incorporating cases. An instructor who chooses the low collaboration video creation route has increased control. However, many new skills may be required. Due to the tools and medium, video creation can be intimidating and have a longer learning curve. Faculty express fear and lack of available time surrounding the use of technology (O’Byrne et al., 2021); these concerns need to be weighed against the benefits of learning a new skill. In the case of videos, instructors have found that generating their videos improves student performance (D’Aquila et al., 2019).

The author has provided three appendices with resources for creating videos. Please see:

- Appendix A: General academic/non-academic guidance.

- Appendix B: A summary of three research-based guidelines for improving videos that the author found particularly helpful.

- Appendix C: Examples of resources available from non-academic sources.

The following section provides a case study detailing the video creation process for a large-scale implementation.

Case Study: Evolving from face-to-face to hybrid with video content

Much academic research considers analyses of a few videos and the impacts of their characteristics, but rarely are large-scale implementations considered. In the spring of 2016, the administration at a large university converted a Business Analysis course from twice-a-week, 75-minute, face-to-face sessions to a hybrid/flipped course (approximately 500 – 800 students per semester in 14 – 20 sections).

Asynchronous videos delivered the content, and a once-a-week face-to-face session was devoted to active learning exercises. Course learning objectives cover knowledge of various business models and tool usage (Excel) to implement the models. Replacing half of the face-to-face sessions with videos covering the business modules allowed for active learning Excel exercises to be implemented during the remaining in-class portion of the course. The administration set the implementation date for the Fall of 2016.

Team

Though all course sections would implement the new format, the administration elected to have a single faculty member implement it. Since this was the first implementation of this hybrid video format at the college, there had yet to be an established formal process for collaboration. The University’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning (CETL) assigned a coordinator and a media specialist to consult on the project.

Video Source

The selection of a video source was a critical step in the process. The content of this course had been established several years earlier by faculty at the university. The content covered was to remain consistent. Historically, a specific textbook was not used for the course, so no textbook videos were available for consideration.

In the beginning, Internet searches helped locate videos, which resulted in videos for the introductory module. As the content became more specific, the difficulty in finding appropriate videos increased.

Desiring video uniformity across the course resulted in the decision to create most of the video content. Creating videos to replace the course lecture content began in the summer. Having taught the course several times over multiple years, the instructor was familiar with the content. However, their video creation skill level was primarily limited to supplementary software training videos.

PowerPoint lectures developed previously served as the basis for the videos. The focus was on taking the content and changing its presentation. Using lecture videos was not considered since videos provided new implementation choices that were unavailable inside the confines of the in-class lecture.

The goal was to take advantage of this new medium, not just move the lecture to video format.

Video creation software

Software and expertise can impact the production value of the resulting videos (Cooper & Higgins, 2015). The software suggested by the university media specialist for creating the videos was withdrawn from the market shortly after the creation of the videos was to start. Without a similar software product available, the decision was made to use videos created as voiceover PowerPoint. Though this had not been the original decision, it was advantageous. Due to the many videos required and limited time to create, using a familiar tool was extremely helpful as the sole video creator. Also, since PowerPoint has a large user base, assistance with the software was only a Google search away.

Other reasons to consider PowerPoint video creation included:

- Since content was recorded per screen, updates were limited to the screens needing improvement instead of redoing the entire video.

- Basics for animations and writing on the screen were available.

- The ability to record non-PowerPoint screen content, such as Excel, eliminated the need for a second tool.

- When considered useful, the instructors can select to appear in a small square (bottom right) on the PowerPoint.

Determining Video Guidelines

Creating a set of cohesive videos required determining guidelines for the overall feel of the videos. The following were some of the major items considered.

Color scheme, layout of introduction slide, font, and size: Providing a consistent look and feel, such as when a business sets its brand image, helps nudge students’ perceptions of the videos. Choices can also give personality (such as developing an avatar) to the course that may be lost outside of a face-to-face environment.

Average video length: Moving to a video format broke the confines of the former contiguous 75-minute lecture. The total length of the weekly video set was approximately equal to the class time replaced. The original videos aimed for the standard 18-minute length of TED Talks. Based on student feedback and research, a later edit reduced the standard length to 6 minutes.

Choice of lecture presentation: Research has considered the impact on lecture/video capture, voiceover presentation, and picture-in-picture learning. However, an instructor must determine which will result in the desired results for their course. Choosing one type of presentation provides consistency; however, using a variety can address a specific need. For example, due to the formulas and relatively busy PowerPoint slides, voiceover was selected for most of this implementation.

Including the instructor on the screen would result in extraneous distractions that would not be beneficial. However, a few video captures were added to increase students’ familiarity with the instructor.

Storyboard and Script

Storyboards are graphical presentations that provide a road map for the video’s flow. Various storyboard methods are available, including creating sketches or using a software program.

PowerPoint’s slide format makes it easy to lay out a storyboard for a video. Following the completion of the storyboard, decisions on formatting, images, and animation usage are made.

Editing

With the video recording complete, it was time to step back and view it with an editor’s eye and as a future student. Is the video communicating the message directly and engagingly? Based on this analysis, the decision to retake or edit was made. Brecht & Ogilby (2008) state that it takes two to four hours to produce a 75-minute video due to the retakes required to correct mistakes.

With limited editing skills, re-recording many early videos was the only solution to fix errors. As the project progressed, developing editing skills became a priority. These improved skills resulted in an improved production process and the ability to finalize videos faster.

Video hosting platform:

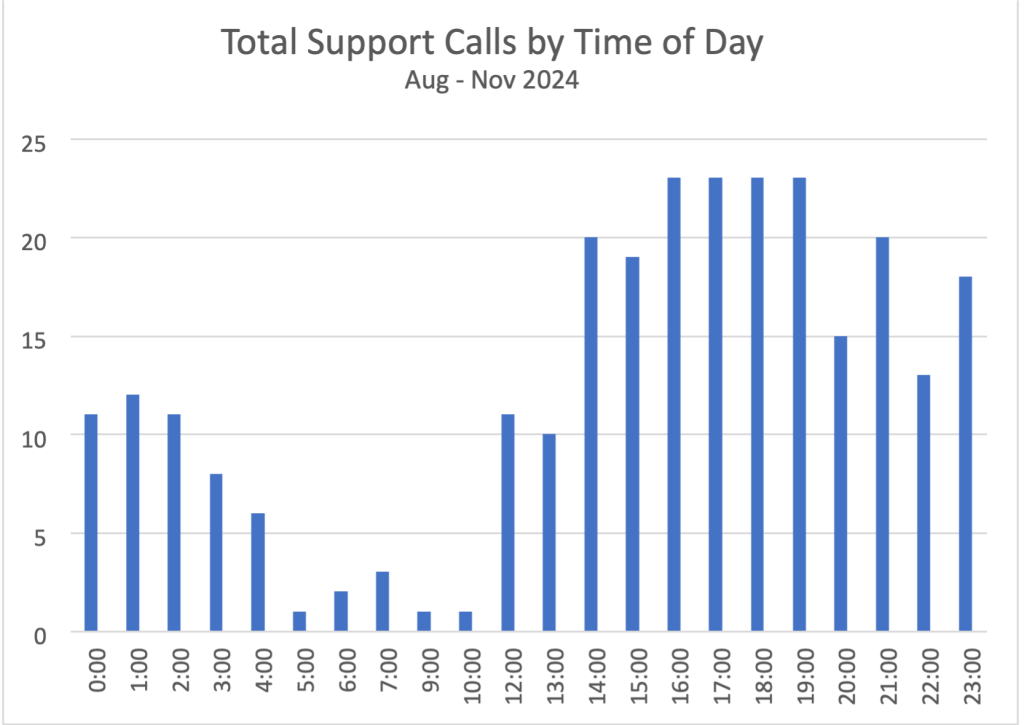

After creating the video, a location to store the video and provide student access was required. The original choice, the logical and most straightforward solution, was to have all the videos reside on the university LMS platform. However, an understanding of the available support is essential. Since students can watch videos at their convenience, they expect high availability, even at night and on weekends. The university platform could not meet students’ expectations of 24-hour, seven-days-a-week video availability and support, requiring the videos to be moved to a third-party online platform in the second year. Chart 1 provides recent data on student calls to the online platform’s help center, which shows a significant amount of demand during evening hours.

Video analytics are commonly available with hosting platforms. This data provides essential information about how students interact with the videos and can be used to guide future modifications. Therefore, understanding what is available before selecting a platform is critical.

Video Creation, Lessons Learned

Looking back on the many hours spent creating videos, the following are general recommendations.

- Video scripts are highly suggested (Weeks & Davis, 2017). Adlibbing can convey the conversational tone of an in-class lecture in the videos. However, it resulted in more retakes and editing without a script to fall back on.

- Set realistic standards, and do not expect to win an Academy Award. It is reassuring that Guo,

Kim, and Rubin (2014) found that high production value might not matter.

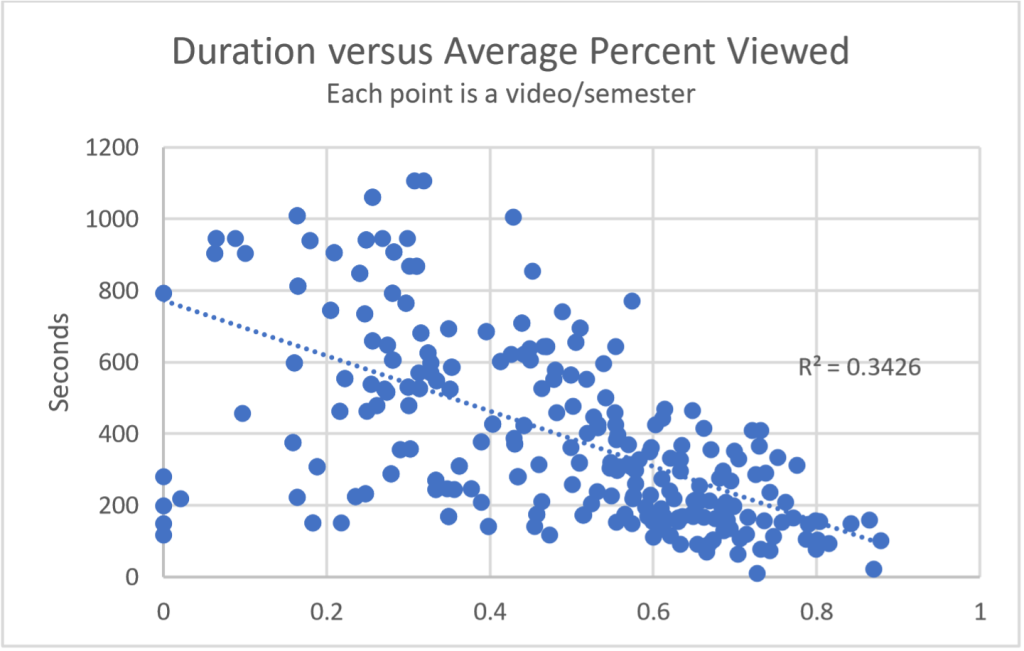

- The length of the video impacts the amount watched. Video hosting sites provide data on items such as the percentage of views. Though this does not guarantee engagement, it provides valuable information. Chart 2 shows the impact of the duration of a video on the average percentage viewed, supporting previous research that students are more likely to watch shorter videos.

- When creating a video, balance the time required versus the shelf life. As with many things, a video students can watch is better than the perfect video that is still unfinished. As video creation has gotten more accessible, the shelf life has gotten shorter (and that is a good thing).

- Every day brings the introduction of a new video creation tool. It is easy to be tempted by the shiny new tool. However, sticking to a known-and-trusted tool has many advantages. Carefully evaluate the tradeoff of the new tool’s learning curve versus the benefits. Many free basic versions of tools are available, but will these limited features and multiple providers satisfy the project requirements?

- In a perfect world, the project’s completion date would be at least two weeks before class started. That was only possible for the first few weeks of video content. Videos often were loaded approximately one week before students began viewing them after the initial stage. The benefit of this just-in-time delivery was the chance to implement lessons learned from current videos and make adjustments moving forward; the cost was increased stress.

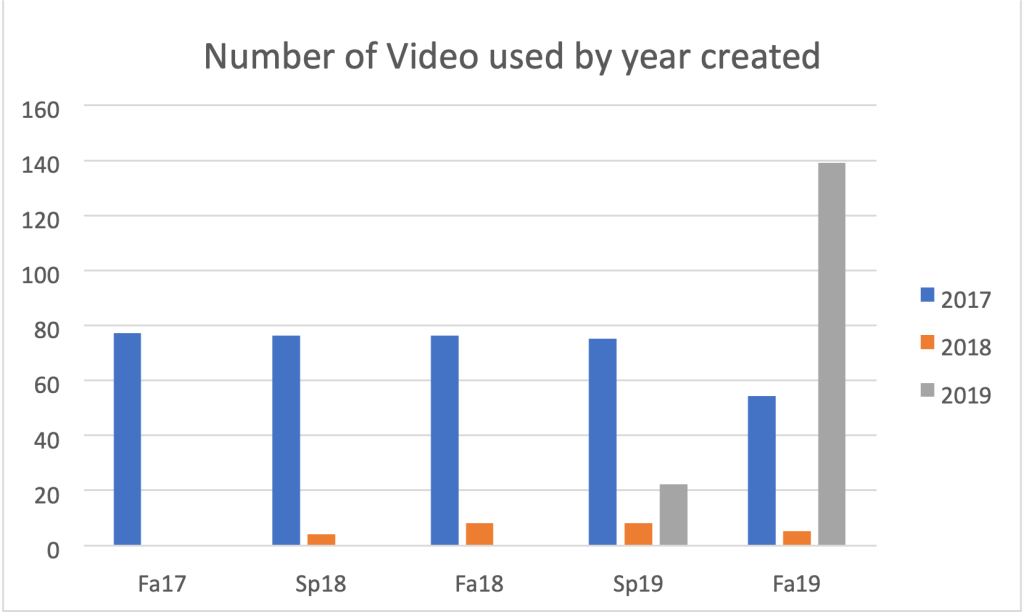

- Finally, even with a perfect process, the first set of videos will not be the final set. Video creation is an iterative process. Expect to create at least a few new videos each semester and realize that major updates will also occur. Chart 3 illustrates when the videos used were created for a given semester. Some semesters had minor updates, and some had major updates (Fall 2019).

Committing to creating video content can seem daunting; however, the advantages of this media far outweigh the learning curve.

Conclusion:

Creating videos might be a skill you do not possess or feel confident in mastering. However, overcoming hesitation and moving forward in this medium has many rewards. Videos are a powerful tool to engage and educate students who have chosen this as their preferred content delivery method. The video content that began as described in this case study continues to evolve and educate students. Results from end-of-semester surveys support the success of this endeavor. See Table 1. As the world and education become increasingly video-based, instructors need to explore creating videos to meet students where they are and use its advantages to help their students learn.

| Fa20 | Sp21 | Fa21 | Sp22 | Fa22 | Sp23 | Fa23 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | 0.170 | 0.121 | 0.169 | 0.166 | 0.204 | 0.208 | 0.191 |

| Yes | 0.830 | 0.879 | 0.831 | 0.834 | 0.796 | 0.792 | 0.809 |

References

Brecht, H. D., & Ogilby, S. M. (2008). Enabling a Comprehensive Teaching Strategy: Video Lectures. Journal of Information Technology Education Innovation in Practice, 71-86.

Chen, C.-M., & Wu, C.-H. (2015). Effects of different video lecture types on sustained attention, emotion, cognitive load, and learning performance. Computers & Education, 80, 108-121. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2014.08.015

Chen, H.-T. M., & Thomas, M. (2020). Effects of lecture video styles on engagement and learning. Education Tech Research Dev, 68, 2147-2164. doi:http://doi.org/10.1007/s11423-020-09757-6

Cooper, D., & Higgins, S. (2015). The effectiveness of online instructional videos in the acquisition and demonstration of cognitive, affective, and psychomotor rehabilitation skills. British Journal of Educational Technology, 46(4), 768–779. doi:10/1111/bjet.12166

D’Aquila, J. M., Wang, D., & Mattia, A. (2019). Are instructor-generated YouTube Videos effective in accounting classes? A study of student performance, engagement, motivation, and perception. Journal of Accounting Education, 47, 63-74. doi:10.1016/j.jaccedu.2019.02.002

Fee, A., & Budde-Sung, A. (2014). sing video effectively in diverse classes: what students want. Journal of Management Education, 38(6), 843-874. doi:10.1177/1052562913519082

Guo, P. J., Kim, J., & Rubin, R. (2014). How video production affects student engagement: An empirical study of MOOC videos. Proceedings of the First ACM Conference on Learning@Scale Conference (pp. 41-50). Atlanta: ACM. doi:10.1145/2556325.2566239

Hoffler, T., & Leutner, D. (2007). Instructional animation versus static pictures: A meta-analysis. Learning and Instruction, 17, 722-738. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.09.013

Lowenthal, P. R., & Cavey, L. O. (2021). Lessons learned from creating videos for online video-based instructional modules in mathematics teaching education. TechTrends, 65, 225-235. doi:10.1007/s11528-021-00581-0

Loya, M. A., & Klemm, T. (2016). Teaching Note—Using TED Talks in the Social Work Classroom:. Journal of Social Work Education, 52(4), 518–523. doi:10.1080/10437797.2016.1198291

Mayer, R. E. (2021). Evidence-based principles for how to design effective instructional videos. Journal of Applied Research in Memory and Cognition, pp. 229–240.

Mayer, R. E. (Nov 2008). Applying the science of learning: Evidence-based principles for the design of multimedia instruction. American Psychologist, pp. 760–769.

Mueller, C., Richardson, J., Watson, S., & Watson, W. (2022). Instructional Designers’ perceptions & experience of collaborative conflict with faculty. TechTrends, 66, 578-589. doi:10.1007/s11528-022-00694-0

O’Byrne, W., Keeney, K., & Wolfe, J. (2021). Instructional technology in context: building on crossdisciplinary perspectives of a professional learning community. TechTrends, pp. 485-495. doi:10.1007/s11528-021-00586-9

Pi, Z., Zhang, Y., Zhu, F., Yang, J., & Hu, W. (2019). Instructors’ pointing gestures improve learning regardless of their use of directed gaze in video lectures. Computers & Education, 128, pp. 345–doi:/10.1016/j.compedu.2018.10.006

Rueda-Gómez, K. L., Rodríguez-Muñiz, L. J., & Muñiz-Rodríguez, L. (2023, April 2023). Performance and mathematical self-concept in university students using Khan Academy. Heliyon, 9(4). doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2023.e15441

Shoufan, A. (2019). Estimating the cognitive value of YouTube’s educational videos: A learning analytics approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 92, pp. 450–458. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.036

Tarchi, C., Zaccoletti, S., & Mason, L. (2021). Learning from text video, or subtitles: A comparative analysis. Computers & Education, 160. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104034

van der Meij, H., & van der Meij, J. (2013, August ). Eight Guidelines from the design of Instructional Videos for Software training. Technical Communication, 205-228.

van der Meij, H., & van der Meij, J. (2013, August). Eight guidelines from the design of instructional videos for software training. Technical Communication, 205-228.

Varkey, T., Varkey, J., Ding, J. B., Varkey, P., Zeitler, C., Nguyen, A., . . . Thomas, C. (2023). Asynchronous learning: a general review of best practices for the 21st century. Journal of Research in Innovative Teaching & Learning, 4–16.

Wang, F., Zhao, T., Mayer, R. E., & Wang, Y. (2020). Guiding the learner’s cognitive processing of a narrated animation. Learning and Instruction, p. 69. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101357

Weeks, T., & Davis, J. (2017). Evaluating best practices for video tutorials: A case study. Journal of Library & Information Services in Distance Learning, 11, 183-195. doi:10.1080/1533290X.2016.1232048

You, J., & Yang, J. (2021). Engaging students with instructional videos Perspectives from faculty and instructional designers. The Quarterly Review of Distance Education, 22(3), 1-10.

Appendix A

Video Creation Guidance and Individual Characteristics:

As a film director makes choices that impact the entire film, the team should make general decisions that guide the overall process before recording the first video. As the scenes in a film flow together, videos for a class should fit together as they guide students in learning the content. The following reviews guidance from academic and non-academic sources on video characteristics that improve learning. Although this research can be used to evaluate videos from other sources, the logical application is for new videos described in category four listed above.

General Guidance: Academic

A director will make choices, such as filming location, which impact the entire movie. In the same vein, researchers have offered guidance for video creation. Based on 20 years of experimental comparisons, R.E. Mayer has applied the science of learning to design multimedia instructional messages. Mayer’s (Nov 2008) Seminal research offers best practices for creating multimedia tools (including videos) for learning. One of the Evidence-Based Principles for the Design of Instructional Videos included the multimedia principle, which states that people learn better from computer-based words and pictures than from computer-based words alone (Mayer, 2021).

Numerous researchers have built on this foundational research (Fee & Budde-Sung, 2014; Cooper & Higgins, 2015; Chen & Thomas, 2020; Van der Meij & Van der Meij, 2016; Guo et al., 2014). In addition, the application of Mayer’s work has led other researchers to develop additional guidelines, such as designing instructional videos for software training (Van der Meij & Van der Meij, August 2013), video production recommendations (Guo et al., 2014), creating a video tutorial (Weeks & Davis, 2017), and software training (van der Meij & van der Meij, 2013).

See Appendix B for a selection of guidelines from three researchers.

General Guidance: Non-Academic

Creating videos has become commonplace. According to Wikipedia, in May 2019, more than 500 hours of content were uploaded each minute to YouTube. The 21st-century device-enabled students have seen so many videos that their exposure may impact on their expectations for videos they view as part of a course. Knowledge gained on creating an engaging video can be helpful, whether from academic research or videos for entertainment, marketing, or education.

A simple internet search, such as “creating video guidelines,” reveals the breadth of these sources.

In addition, sources exist for useful video creation topics such as how to write a script, storyboarding, and video production guidelines. Such sources can provide helpful guidelines, such as using the “Rule of Thirds” to guide the placement of items on the screen.

The tools available for creating videos are vast. Whether it be a tool that added video creation to its original software (PowerPoint), focused on creating various types of content (Adobe), or a video hosting site (Wistia), these companies often provide guidance on the creation of videos. Consideration of these resources should made during the tool selection process. See Appendix C for examples of resources available from two sources.

Individual Video Characteristics Guidance: Academic

Research on the impact of specific video characteristics on learning tends to be conducted in a controlled research environment, providing narrowly applied guidance on the learning impact of specific choices. It is not the intention to apply these guidelines to the entire video creation process; instead, they should be applied selectively to individual videos.

Examples of this type of guidance include: avoiding the use of subtitles (Tarchi et al., 2021), the instructor should use pointing gestures to improve learning regardless of the use of directed gazes (Pi et al., 2019), adding visual signaling or cueing can improve learning outcomes (Wang et al., 2020), handdrawn types of lectures videos are more engaging (Chen & Thomas, 2020), instructional animations have an advantage over static pictures (Hoffler & Leutner, 2007), and the choice of lecture presentation, including lecture capture, voiceover presentation, and picture-in-picture impact on student performance (Chen & Wu, 2015).

Appendix B

Summary of three sets of research-based guidelines for improving videos.

Mayer R. E. (2008, November). Evidence-Based Principles for the design of multimedia instruction.

- Reduce Extraneous Processing

- Coherence: Reduce Extraneous material.

- Signaling: Highlight essential material.

- Redundancy: Do not add on-screen text to narrated animation.

- Spatial contiguity: Place printed words next to corresponding graphics.

- Temporal contiguity: Present corresponding narration and animation at the same time.

- Manage Essential Processing

- Segmenting: Present animations in learner-paced segments.

- Pretraining: Provide pretraining in the name, location, and characteristics of key components.

- Modality: Present words as spoken text rather than printed text.

- Fostering Generative Processing

- Multimedia: Present words and pictures, rather than words alone. dropped in 2017)

- Personalization: Present words in a conversational style rather than a formal style

- Use a human voice, not a machine, Added in 2017.

- Use human-like gestures and movements. Added in 2017.

Van der Meij & Van der Meij. (2013, August). Guidelines for the design of instructional videos for software training

- Provide easy access: Craft the title carefully.

- Preview the task: Promote the goal.

- Make tasks clear and simple: Follow the user’s mental plan when describing an action sequence.

- Draw attention to the interconnection of user actions and system reactions.

- Use highlighting to guide attention.

- Use animations with narration.

- Be faithful to the actual interface in the animation.

- Action and voice must be in sync.

- Use a spoken human voice for the narration.

Guo, Kim, & Rubin. (2014). How video production affects student’s engagement

- Invest in pre-production effort. High-quality pre-recorded classroom lectures, even when chopped up, are not as engaging due to lack of pre-production effort.

- Edit out pauses and filler words in post-production.

- Shorter videos are more engaging, ideally less than 6 minutes.

- Produce a video with a more personal feel versus a studio recording.

- Recordings Interspersed with instructor talking head with slides are more engaging than slides alone.

- Speak fast and have high enthusiasm.

- Record Khan-style tutorials when possible. If you use slides, sketch over them.

- Students engage differently with lectures (optimize for first-time watching) and tutorial videos (support re-watching and skimming).

Appendix C

Examples of Resources Available From Non-Academic Sources

The following list some examples from two companies in the video creation space.

Adobe:

- Video production: A beginner’s guide | Adobe

- How to write video scripts | Adobe

- How to get started on storyboarding | Adobe

Wistia:

- How to Screen Record on Mac and Windows: Learn how to record your screen on a Mac or Windows computer.

- 9 Best Online Video Editors For Creating Great Marketing Videos: Here’s a list of some of the best online video editor platforms.

- How to Add Closed Captioning to a Video

- How to Video Record Yourself Presenting A PowerPoint: Learn how to record yourself on a webcam presenting PowerPoint slides using just your laptop.