Design, Implementation, and Reflection

From an Interdisciplinary Course in Museum Studies

Brenna L. Decker, Ph.D.

Abstract

In Spring of 2023, I developed a special topics course titled Collection Material Handling to introduce students to museum management using Utah State University collections on the Logan, UT campus. The cross-listed upper-level course brought 16 USU students together from two disciplines: anthropology and natural sciences. The publication details how I used various learning theories to guide the creation of course content and how I structured and implemented activities in the classroom and in the collections. Examples of worksheets, activities, student feedback, and recommended improvements to assignments are provided. I encourage instructors to use these resources within current course offerings or implement their own versions of the course within and beyond the USU campuses.

Keywords: course development, collections, ungrading, experiential learning, natural science

Introduction

University campuses boast a broad range of resources for students during their education and preparation for a future career. Many universities host various natural history, anthropological, and fine art collections that are used within coursework and university-led research. In general, museums and collections provide information for all of society, including historic assessments, insight on future directions, and preserving the records of political and climate changes. Within museum studies, New Museum Theory (Marstine, 2005) emphasizes that a museum is not an isolated entity but serves the community in research and education while addressing current societal issues.

Even under this broad definition of museum studies, coursework tends to be isolated within the humanities departments at universities. I developed a course that expanded on the idea of museum studies to include both the sciences and the humanities, creating a diverse classroom that facilitated broad critical thinking. After two years of development and discussions across Utah State University (USU) departments, I facilitated a special topics course titled Collection Material Handing in Spring of 2023.

This publication aims to detail the course design from the Spring 2023 semester, the various theories and teaching strategies employed during the design, some example worksheets and activities, and provide a discussion about changes and additional suggestions for future implementation of similar courses or assignments. It is my hope that more courses and activities such as these be designed, incorporated, and taught across the country.

Course Design Background

At USU, the College of Humanities and Social Sciences (CHaSS) offers a Museum Studies Certificate program. The focus of the program has remained in the social sciences, with little inclusion of other collections such as natural history (animals, geology, etc.). Of the 12 collections held on the USU Logan, UT campus and the one off-campus collection, ten are in fact natural history collections (Table 1). Each collection has a unique mission within the university and the community. For example, the Geology Museum, Museum of Anthropology, Intermountain Herbarium, and the Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art each host a public-facing exhibit space for education, and storage and workspaces for research. In contrast, the Library Special Collection is used for research but has restricted public access, with periodic participation in creating public exhibitions. Other collections in several USU departments are primarily used for research with no public access. This includes the lab-specific herpetology and entomology collection. Still others within these departments are used specifically for coursework, including the mammalian, ornithology, and osteology collections.

The gap between what are considered the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ sciences (Biglan, 1973; Neumann, 2001) creates an artificial divide where collaboration and critical thinking may be stifled by reducing student’s exposure to other disciplines and viewpoints. At the university level, this divide is seen in course names, separating courses and topics taught based on college and department. While most universities have used cross-listing courses between multiple departments to allow faculty to teach in multiple disciplines (Curry et al., 2022), a cross-listed course may provide more opportunities for students by reducing or eliminating the ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ sciences divide. The cross-listed choices used for this course (Anthropology, Biology, and Wildland Resources) instead centered on providing opportunities for natural science-focused students to explore museum studies and for anthropology students to explore the many objects that they may encounter in a collection. Cross-listing this course between departments also provided students applicable credits for their degree requirements (Macalester College, 2023).

| Collection Name | Building

(room #/ address) |

Research | Teaching | Resources |

| Museum of Geology | GEOL (203) |

X | X | https://www.usu.edu/geo/info/geology-museum |

| Herpetology Collection | BNR | X | Collection for teaching courses | |

| Library Special Collections and Archives | Merril-Cazier Library | X | X | https://library.usu.edu/archives/collections/sections |

| Beetle Colonies (Osteology) | VSB | X | Research and teaching use | |

| Entomology Museum at Utah State (EMUS) | BNR | X | Research collection; https://www.pittssadlerlab.com/museums/emus | |

| Ichthyology Collection | BNR | X | Collection for teaching courses | |

| Mammalogy Collection | NR | X | Collection for teaching courses | |

| Mason Wildlife Exhibit | NR (Quinney Natural Resources Library) |

X | https://qcnr.usu.edu/quinney/masonwildlife | |

| Ornithology Collection | BNR | X | Collection for teaching courses | |

| Museum of Anthropology | Old Main Hill (252) |

X | X | https://chass.usu.edu/anthropology/museum-of-anthropology/ |

| Nora Eccles Harrison Museum of Art (NEHMA) | NEHMA (650 N 1100 E Logan, UT) |

X | X | https://www.usu.edu/artmuseum |

| Intermountain Herbarium | The Junction (lower level) |

X | X | https://www.usu.edu/herbarium |

| Zootah | (419 W 700 S Logan, UT) |

X | X | https://zootah.org |

Note: List of USU campus and off-campus collections visited during the Spring 2023 Collection Material Handling course. Building names are provided, with a room number or address included for public-facing collections; links to websites are provided when available. Each collection also is used for either research, teaching, or both where marked. The ornithology lab was optionally held over spring break and consisted of practicing making study skins from cedar waxwing birds who perished after window strikes on the USU campus. GEOL = geology building; BNR = biology and natural resources building; VSB = veterinary science building; NR = natural resources building.

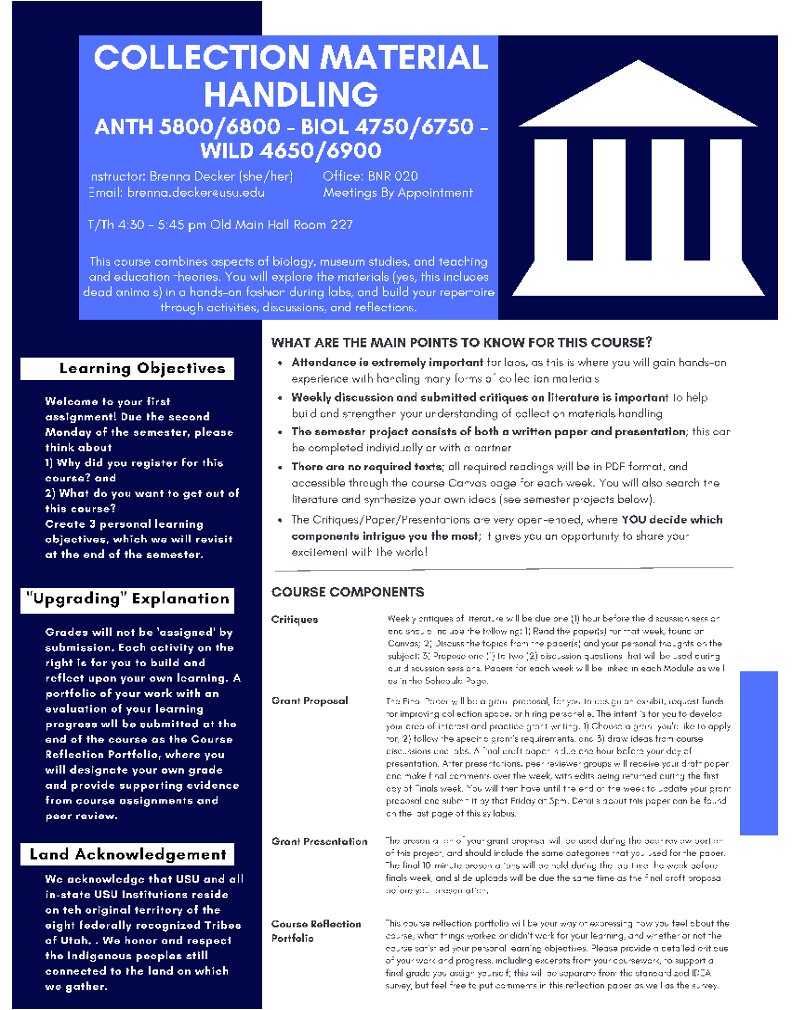

The complete name of the course was, thus, Collection Material Handling, ANTH 5800/6800 – BIOL 4750/6750 – WILD 4650/6900. The course numbers below 6000 were for upper-level undergraduate student registrations, while course numbers above 6000 were for graduate level student registrations. In total, the course brought 13 registered undergraduate and graduate students, along with three additional graduate student observers, into 12 on-campus collections and one off-campus living collection.

The Collection Material Handling course focused on building metacognition and problem solving in the field of museum studies and collection management. The objectives for this course were:

- to get students into the collections and provide hands-on experience with collection objects,

- to develop critical thinking skills through cross-disciplinary conversations around the topic of museum studies, and

- to provide practice in grant writing and self-assessment.

All topics included in the course were drawn from multiple sources, including the Entomological Collections Network workshop (which I attended in the summer of 2022; https://ecnweb.net/workshop/), the Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections (SPNHC; https://spnhc.org/resources/?fwp_resources=best-practices), and the American Alliance of Museums (AAM; https://www.aam-us.org/category/research-and-reports/). Course topics included management planning, storage facilities, digital collections, collection assessments, integrative pest management and conservation, interpretation, and surveying (see Appendix A). Additional topics discussed throughout the course included developing a curation philosophy, practicing grant writing, and conducting self-assessments.

Learning Theories and Teaching Methods, with Examples

Learning theories are typically restricted to education and psychology departments, but often can provide insights for anyone who engages in some form of instruction. Education and adult learning theories primarily drove the creation and implementation of the activities throughout the semester. The theories used to structure the timing of topics and class activities included Proster theory (Hart, 1991) and the combination of discovery learning, meaning making, and constructivism (Bruner, 1996, pp. 19-20; Silverman, 1997).

Proster theory implies the brain actively participates in the learning process. Mental capacities can be taken up with extraneous concerns such as food insecurity, family matters, other coursework, and other student responsibilities (Hart, 1991). These distractors often detract from the learning process and should be acknowledged when designing activities throughout a semester. This includes addressing holidays from various cultures, school breaks, general timeline for course midterm examinations, and current world events.

Discovery learning, meaning making, and constructivism are complementary terms describing the use of hands-on experiences to supplement and build on previously learned knowledge. The goal is to provide an environment for discovery and connection, often leveraging group participation through discussions and activities, to adjust or supplement attitudes – and consequently behaviors – to a particular topic (Bruner, 1996, pp. 19-20; Silverman, 1997). Building connections between past and new information subsequently strengthens critical thinking.

This section contains details about various course design methods and how they were applied throughout the Spring 2023 course.

Backwards Design

Backwards design is a process by which an instructor or educator first identifies desired or expected outcomes, and designs the lecture, activity, or full course to meet those specific outcomes (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005). These outcomes should be composed based on the academic and intellectual level at which the instructor will teach. A single lecture may have one or two desired outcomes, while a course may have outcomes specific to university or institution requirements. For a given topic, the instructor first identifies what they want students to learn, remember, or do. Once that outcome is identified, the instructor can then structure a lecture or activity that directly leads to students successfully accomplishing that outcome.

For example, backwards design was used to create an in-class assessment activity based on surveying methods. As part of museum studies, direct handling of collection objects can spur ideas about educational activities. To assess if those educational activities created a desired outcome, which is often to change or strengthen an individual’s mindset on a topic, a collection manager may need to conduct surveys and elicit responses from participants. Therefore, a desired outcome for the survey lecture was “to have students design and critique surveying methods”. The outcome was inspired by a theme statement activity used in the Natural Resource Interpretation course (NR 4600/6600) taught by Dr. Chris Monz at USU during the Fall 2021 semester in which I served as a co-instructor. The activity involved creating a theme statement for a science communication topic presented in class.

To address the surveying outcome, the lecture was formatted to introduce surveying methods with an associated activity. For the activity, students were given the prompt “You want to know if an exhibit on climate change altered how people view their relationship with the environment” and were provided the exhibit’s theme statement “Changes in our global climates can drastically affect the way of life for all organisms, including humans”. This was followed by the questions “Who is your target population?”, “How do you want to conduct the data collection?”, and “Create two questions you want to include in your survey.” Students organized themselves into groups of two or three to address these questions. After 20 minutes, each group wrote one of their survey questions on the board. As a class, we then evaluated the wording and hypothesized potential results and their meanings. A student-led discussion ensued over biases in survey questions. Students brought up method design considerations, including if asking one question before another may influence a survey participant’s response, how delivery method (passive or active recruitment) could alter responses, or if participants would have access to electronics to take a virtual survey. In this example, the activity directly achieved the initial desired outcome formulated prior to the activity design.

Interleaving

Spiral learning (Bruner, 1990) and interleaving (Lang, 2016, pp. 63) describe methods to refresh students on the topics from earlier in the course and to connect future topics. Both terms are used to describe a way to refresh students on the topics from earlier in the course and to connect future topics. Interleaving information can strengthen the student’s knowledge base on topics and promote the development of critical-thinking skills, while also applying that information to new scenarios. These methods can be leveraged to dive deeper into concepts and connect seemingly different or even contrasting topics within a course to promote metacognition.

Interleaving was key to developing lecture and discussion topics and solidifying concepts during collection visits. The collections housed at USU varied greatly in budgetary restrictions, locations, and management. The first lecture introduced students to management planning, with the paired collection visit to The Geology Museum on the USU campus. This museum encompassed many aspects of collections, from the public-facing museum and education space to geologic and fossil research and cataloging. Visiting this museum first set up future opportunities to draw comparisons between collections, which were often smaller or had differing mission statements. Comparing the mission statements, funding sources, management systems, storage capabilities, and the use of collection items or spaces for the various collections allowed students to directly see the effects of each component and how the collections manage their personnel and resources. As the course progressed, more variations in management were encountered, and students commented on the diversity of procedures that directly led to various standard operating procedures (SOPs) within a collection.

Lecture Pauses

Listening to an hour of lecturing may work for some students, but studies have shown that while students think they are learning by simply listening, they do not score higher on tests compared to participants who engage in active learning (DaRosa et al., 1991). Instead, altering or changing classroom pedagogy creates a sense of belonging and can deepen content connections that facilitate critical thinking (Lang, 2020). Incorporating group and full class discussions within the traditional lecturing structure enhances memory (Markant et al., 2016) and demonstrates the applicability of the topics discussed to many different fields of study or interest (Nelson & Crow, 2014). Presenting the lecture structure and identifying points of activity changes before class begins also lets students prepare for the day’s lecture (Lang, 2020, pp. 159).

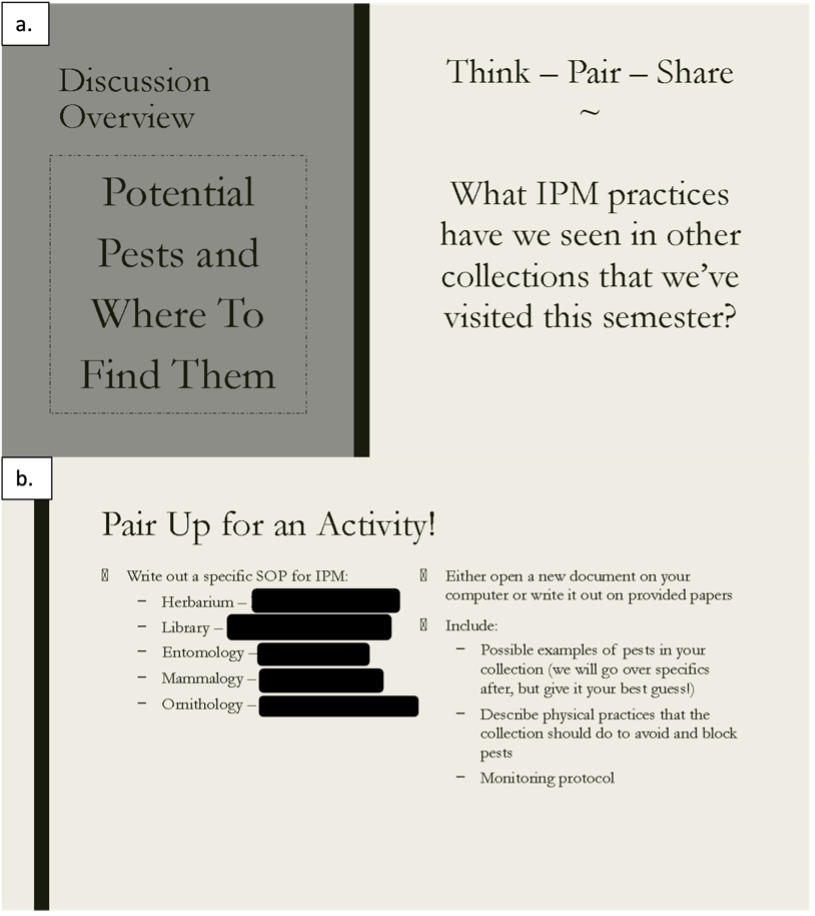

Grabbing students’ attention at the beginning of a course or a lecture period can be difficult. There are many distractions that a student might face in their daily lives; hunger, coursework stress, personal or familial health concerns, financial insecurity, and many others. These distractions within a classroom have been highly studied, with a thorough overview provided by James Lang in his 2020 book Distracted. To grab student’s attention, I began each lecture with a think-pair-share exercise (Rice, 2018, pp. 145). I posed questions relating to the topic of the lecture, sometimes taken directly from student comments within the virtual discussion board submission prior to lecture. For example, during the virtual discussion related to integrative pest management (IPM), I had students read and comment on an article describing IPM planning. At the beginning of the lecture, I asked students to think about the IPM measures they saw when visiting previous collections (Fig. 1a). I then discussed IPM practices before having students pair up and create a standard operating procedure (SOP) for IPM based on a given collection (Fig. 1b).

Note: Example slides from the integrative pest management lecture, including a) pre-lecture think-pair-share pause connecting the lecture topic to previously visited collections, and b) an activity for pairs of students to create and evaluate an IPM plan for their given collection (student names redacted).

Pauses in the middle of the lecture relate to attention restoration theory (Kaplan & Kaplan, 1989). This theory, originally centered on proving space in nature to reorient attention after directed attention is fatigued, can be applied not only in the workplace (Lee et al., 2015) but in the classroom (Lang, 2020, pp 163). The restorative aspect of pausing and changing activities does not have to be an extensive event but can be achieved in short amounts of time through micro-breaks (Lee et al., 2015). Changing the pace of the lecture can reinvigorate student interest and participation (Bunce et al., 2010). Incorporating deliberate efforts of student engagement “can not only be seen as a way to present concepts in an alternate format but may also help engage students in subsequent lecture teaching formats” (Bunce et al., 2010). The pauses I used within the lecture mainly included group activities followed by sharing ideas and leading a class discussion, much like that seen with the IPM lecture (Fig. 1b). I noticed heightened attention to additional lecture materials after each mid-lecture activity, as the class was keen on stating their thoughts and asking additional questions.

Ungrading

Ungrading is a system which uses various forms of assessments and feedback throughout a semester (Blum, 2020, pp. 2). This is the opposite of giving a letter or percentage grade to individual assignments that are then added or averaged for a final course grade. The focus falls on individual learning, written and verbal feedback, peer engagement, and self-evaluation instead of hyper focusing on memorization and information regurgitation to pass tests (Blum, 2020). This practice has been used extensively in the humanities and social science courses across the United States, with a slow progression with STEM field adoption (pers. comm.). Ungrading can be applied at many levels, from individual assignments to the full course.

The learning objectives, course level, elective status, and the amount of course content used in progressive upper-level courses help identify areas or whole courses ideal for conversion to an ungraded system. In museums and collections, each situation may require different approaches or techniques. The learning objectives for this Collection Material Handling course focused on practice and critical thinking, emphasizing flexibility to address museum and collection related concerns or emergencies. The course was designed as an experiential upper-level elective, with no direct links to other courses offered by the university. Consequently, I chose to apply ungrading to the full course.

Most enrolled students had never taken a course that used the ungrading practice. Therefore, it was important to address the format and requirements at the beginning of the course, with subsequent discussions with students at the midterm and end of the course. I replaced letter grades on assignment submissions with extensive feedback and opportunities to re-submit. I wanted students to focus on how they saw themselves progress within the course and with applying course content. Because this was an unfamiliar format, I provided context for students related to each traditional grade designation, following USU grading guidelines. Each letter grade and percentage was given specific criteria within the syllabus to provide a structure for student’s self-assessment on their participation in the virtual and in-person discussions, classroom activities, and collection visits. For example, the difference between the A (100%) and A- (93%) was whether students provided explanations for any late or missed assignment within the learning portfolio and addressed missed content.

To do this within the Canvas learning management system, each assignment and discussion was designated as ‘Ungraded’ and were not part of the gradebook. Students accessed these assignments and feedback through the Assignments, Discussions, and Quizzes tabs in the Canvas navigation pane, as well as within each week’s webpage through links. The student’s final assignment was to compile their personal learning portfolio and evaluate their own thoughts and understandings of managing collections and handling collection objects. This was the only gradebook entry, out of 100 points, where grades discussed during the final individual meetings were posted and subsequently submitted to the university. More about the learning portfolio is described later in this publication.

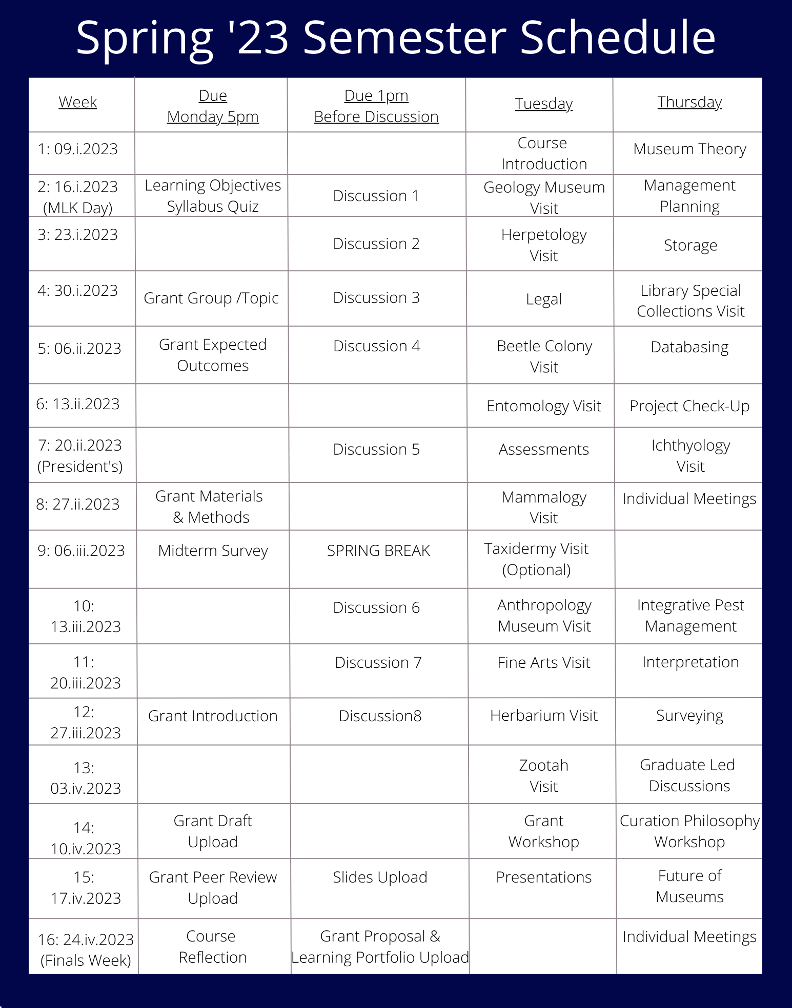

Example Activities from the Course

During the 16 weeks of the USU spring semester, there were 11 days of discussion with specific topics, 12 days visiting collections with one optional lab over spring break, two days of graduate-led discussions and presentations, two days working on student semester projects, and one day for a guided writing workshop (see Syllabus in Appendix A). Below are a few examples of activities used during the course to achieve the learning objectives. The text primarily relates to museum studies, but worksheets and games like those below can be adapted and modified to address the needs of other courses and disciplines.

Management Planning Game

A museum worker often must make decisions based on available information and prior training. Being prepared for many situations, including burglary and theft, pest infestations, and administration requests, helps maintain proper museum function and support the preservation of collection materials. Therefore, introducing students to the topic of museum management and planning at the beginning of the course set the stage to discuss best practices in subsequent lectures and collection visits.

During the first lecture, the class discussed institutional, national, and international policies that should be in place within a museum depending on the museum’s mission statement. To gain practice in utilizing resources and addressing museum issues, the class played MonoPolicy, a monopoly-like board game created based on John Simmons’ book Things Great and Small: Collections Management Policies (Simmons, 2017). The game is free to download and print; it includes the board, the problem, resource, and policy cards, and instructions (https://www.museumstudy.com/monopolicy).

The game provided students in groups of four a chance to practice problem solving based on a problem card, using the resource and policy cards they picked up throughout the game. In this format, critical thinking skills and collaborations (Learning Objective #2) was practiced through gamification (see Landers et al., 2015). The game instructions encouraged collaboration. The act of trading cards communicated needs and facilitated the assessing of options to solve problems in the most appropriate and effective way. A few of the problem-solving strategies used by students included a) having a management policy and off-site backup of collection databases in case of computer crashes, b) installing camera systems in response (or in preparation for) issues regarding unlocked doors after hours and suspected theft, and c) establishing public relations protocols or hiring a public relations representative to address any negative media coverage about collection items within the institution. These problem-solving skills take practice, but are broadly used in all disciplines.

Database Exploration Activity

Public-facing databases are becoming more prevalent and are more recently required to some extent through funding agencies (e.g. National Science Foundation, 2023). There are many types of databasing systems and software available, and it is often the case where institutions use different programs with different layouts and features. For staff members charged with managing a collection, it is important to know 1) how a database and its features align with the collection’s mission, and 2) how the database will be used by internal and external personnel. Exploring different established public datasets provides first-hand experience in interface design and understanding the accessibility of collection material information.

The database lecture was delivered towards the middle of the semester, after students had opportunities to explore several collections on campus. The database lecture consisted of four parts (Fig. 2). The first and third parts were lecture and discussion based, and parts two and four, as seen in the example worksheet, were conducted in small groups of two or three students. The assessment of these public-facing databases emphasized, again, critical thinking (Learning Objective #2) and tied into what students had so far experienced in the course through collection visits.

Each group received a worksheet with a different database link; these databases were from a variety of collections ranging from art, history, and the natural sciences. Groups were first asked to agree on a topic or item they would search for within their provided database. Questions about ease of access address how quickly the answers were found, or if the publicly available information is sufficient for their object. After discussing each group’s findings with the full class, students were asked to contemplate the questions in part four on their own before discussing with their group, and subsequently discussing the groups’ answers with the class. This think-pair-share exercise (Rice, 2018, pp. 145) included considerations in web page layout, development of holistic thinking addressing the possible goals of a viewer or researcher, and the ability to obtain the desired information based on various search terms. These considerations directly relate to cohesive public outreach and engagement using the resources within an institution.

Figure 2: Worksheet for Database Exploration Activity

Given Institution and Webpage: Intermountain Herbarium at Utah State University | https://herbarium.usu.edu/

Choose a group of organisms or a topic you would like to search for:

*If you cannot find your topic after going through the website, select another topic to investigate.

- How easy is it to find the database portal for the collections?

- How many steps does it take to get to your chosen dataset?

- What are your comments about the layout?

Now, choose one item or specimen that you would like to know more about:

- What information is presented?

- What information do you wish would be included? Why?

Think about the following questions, and talk through them with your group member.

- Is the information of your chosen specimen important? Why?

- How can this information be used?

- How reliable do you think this information is and explain why?

Present your chosen specimen to the class, explaining your reasoning for each question.

- Identify your specimen, including the name of the organism or creator (artist).

- What information is on the specimen, why is that info important, and how reliable do you think this information is? (Part 2 #4, Part 4 #1-3)

- What do you wish was included that is currently absent, and why? (#5 of Part 2)

Note: Example worksheet for the databasing discussion and activity. There were four parts to this discussion day; group work was done during parts 2 and 4, followed by full-class discussions.

Assessing a Collection

Assessing the state of a collection includes examining museum objects with standardized criteria. These assessments help a collection manager identify areas of critical need and provide statistics on collection holdings. This can be incredibly important for collections when securing funding for collection infrastructure or hiring technicians to rehouse and catalog objects. Besides providing a standardized assessment for critical needs, an assessment can also provide information regarding current holdings that may be useful for understanding current teaching and research opportunities.

At USU, the ichthyology (fish) teaching collection holds older specimens of fish primarily from the Rocky Mountain region along with representative species for the major fish clades. The collection is strictly used during the fish ecology course for taxonomic identification practice. At the time of this publication, this teaching collection was stored underneath a basement stairwell due to building renovations and constraints on available space. To compound the storage issues, there was no designated curator or manager for this collection; whoever taught the fish ecology course was put in charge of the teaching collection during the semester.

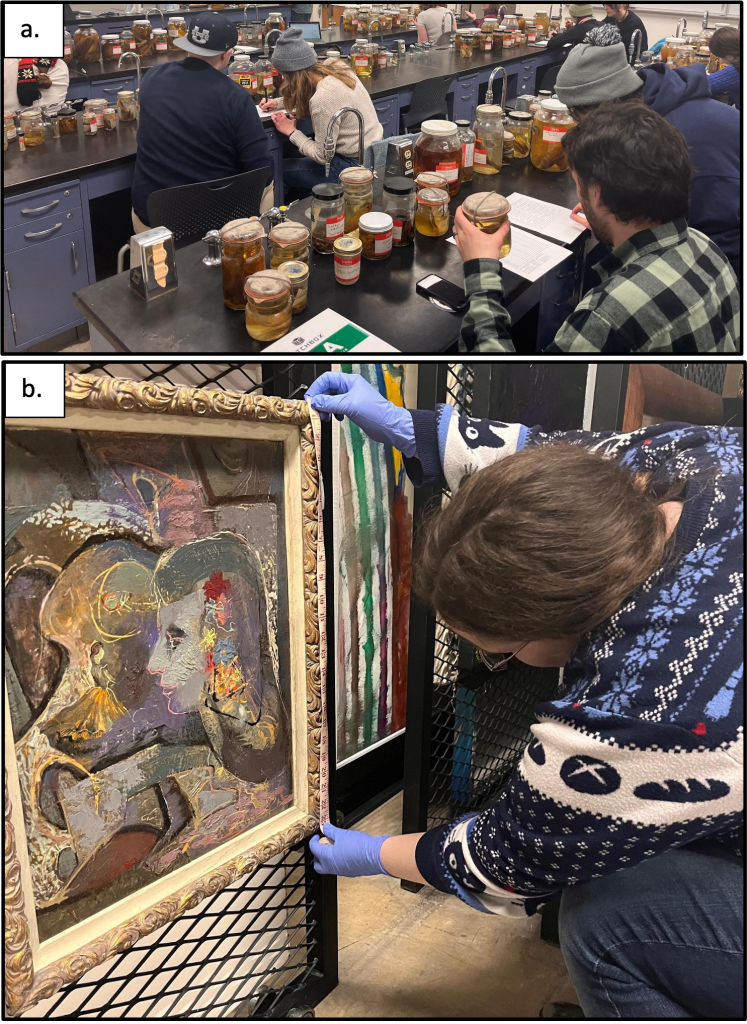

Because of the storage conditions, this collection needed an assessment of specimen damage and storage containers. The ichthyology assessment worksheet, modified from an entomology assessment worksheet, provided space for notes and descriptions of jar and shelf scores for each cabinet (Fig. 3). Students worked in groups of two to determine damage level and level of needed attention (Fig. 4a). Students were proactive in asking questions about types of damage and participated in refilling jars where the ethanol had evaporated (Learning Objective #1). Not only were students gaining hands-on experience, but the assessment results can be used to secure further funds for appropriate storage containers that will aid in future courses.

| Collection | Recorder(s) | ||||

| Date | |||||

| Time | |||||

| Cabinet # | Shelf Curation Level [1 (Immediate attention) – 3 (good condition)] |

||||

| Shelf # | |||||

| # of Jars | |||||

| Jars | Taxon | Liquid Level | Specimen | Jar Condition | Level Assigned |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jar 1 | |||||

| Jar 2 | |||||

| Jar 3 | |||||

| Jar 4 | |||||

| Jar 5 | |||||

| Jar 6 | |||||

| Jar 7 | |||||

| Jar 8 | |||||

| Jar 9 | |||||

| Jar 10 | |||||

| Jar 11 | |||||

| Jar 12 | |||||

| Jar 13 | |||||

| Jar 14 | |||||

| Jar 15 | |||||

| Jar 16 | |||||

| Jar 17 | |||||

| Jar 18 | |||||

| Jar 19 | |||||

| Jar 20 | |||||

| Jar 21 | |||||

| Jar 22 | |||||

| Jar 23 | |||||

| Jar 24 | |||||

| Jar 25 | |||||

| Jar 26 | |||||

| Jar 27 | |||||

| Jar 28 | |||||

| Jar 29 | |||||

| Jar 30 | |||||

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |||

| Liquid | Below specimen | At specimen | Above specimen | ||

| Specimen | Heavy damaged, broken | Some damage, tears | No physical damage | ||

| Jar | No lid, cracks | Loose lid | Tight lid, no cracks | ||

| Level | Immediate Need | In Need | Acceptable | ||

Note: Assessment worksheet for the ichthyology teaching collection, modified from the assessment worksheet for entomology provided by the ECN collection management workshop and the Smithsonian Institutions.

Accessioning Donated Artwork

Objects are often donated to museums from other collections, from other researchers, or from hobbyists who have collected materials over years (and sometimes generations). The process of incorporating these objects into a collection is called accessioning. Recording the condition of these donated materials is critical for identifying any future damage done to the object. A donated object is typically given a collection number during the accessioning process, which helps track the item and its storage location, the item’s condition, and the object’s use in exhibition and research.

The Nora Eccles Harris Museum of Art (NEHMA) and other collections on the USU campus accept many donations throughout the year. NEHMA had accepted a donation of various ceramics and paintings at the end of the fall semester preceding this course’s offering. Due to the many events and exhibits hosted by NEHMA, many items, such as this donation, were backlogged. Backlog within a collection can severely hamper education, research, and maintenance of storage space; they also take up space and have higher risks of degradation.

Addressing backlogged items is a primary goal of many museums and is often completed by volunteers or technicians when available. In the case of NEHMA, students in this course assisted in addressing this backlogged donation. In groups of two, students followed the established protocols outlined by NEHMA and assessed damage based on provided scales and terminology (Fig. 4b). As part of this experience, students learned about the various ways to measure non-uniform objects, how to identify damage using established terminology, and explored the various considerations when storing various art media (Learning Objective #1).

Note: Images taken of students during a) the ichthyology teaching collection assessment and b) accessioning backlogged donated items for NEHMA. Both activities were hands-on experiences conducted with the help of the respective collection managers.

Grant Writing

Museum funding is diverse, with much of the funding provided by government (mostly local and state), grants, and private donations (Katz & Merritt, 2010). In most cases, museums must provide a proposal for their funding requests and budgetary justifications. This includes writing grants for specific museum needs, which can range from storage materials, hiring technicians, or acquiring additional items related to the museum’s mission statement. Writing as a soft skill is required for many careers, but can often be overlooked or not practiced at the college level.

Because most collegiate students do not receive grant writing practice, the semester project focused on critique-driven grant writing (Blum, 2020, pp. 123). For all registered students in this course, this was their first introduction to the grant writing process. The grant writing project encompassed the entire process, including selecting a grant to apply for, working with a collection manager to identify a need, and composing a full proposal (Learning Objective #3) and pitching the proposal during a 5-minute lightning talk. The original worksheets used and subsequently modified to guide students through the writing process can be found at https://ruralhealth.und.edu/grant-writing/worksheets (Center for Rural Health, 2022), which are based on the book Winning Grants Step By Step by Mim Carlson (2002).

The timeline for this semester-long project was organized based on backwards design. Several weeks at the start of the semester were used to 1) get students familiar with museum studies, 2) help students identify their interests and connect them with a collections manager, and 3) provide peer discussions on proposed grant topics. While expected outcomes are generally placed at the end of a grant proposal, addressing this during the first half of the semester helped students identify an end-goal for their grant. The methods were then developed to directly achieve those outcomes, and finally a background section was written to put everything in context within museum studies. A more detailed description of the structure and timing of the grant writing project sections is presented in Appendix B.

Curation Philosophy

Job applications often request specific statements of interests, from research and teaching statements to diversity philosophies. These statements provide a cohesive summary of the persons’ ideas on the subject, a discussion on their past or current involvement or thinking about the subject, and self-assessments for future involvement within the subject. Curatorial philosophies are another statement often requested in applications relating to museum work.

On the last day of the course, students had an opportunity to reflect on what they learned and how museum work aligns with their core values. Identifying individual core values can be used to determine individual attitudes towards and within various careers (Hitlin, 2003; Marcus & Roy, 2019). These values can be concepts or beliefs that link to or influence an individual’s behaviors across many (or all) situations (Hitlin, 2003; Schwartz, 1992).

Students were asked to think about their core values, and how those values align with a component of museum studies that they learned during the course (Fig. 5). The worksheet provided a step-by-step pathway to help students link values to museum studies topics. First, students identified their definition of curation, followed by identifying their core values and their reasons. At this point the class paused to discuss how different values can be linked to museum studies. A few examples of values included ‘family’, ‘environmentalism’, and ‘history’. After identifying how each value related to work done by museum personnel, students were asked to identify an important function of the museum and how that function satisfied their core values. The remainder of the class period developed these thoughts into sentences. The development of teaching, research, and leadership statements can follow the same process used to create these curatorial philosophies.

Figure 5. Guided Curation Philosophy Activity Worksheet

Provide your definition of ‘curation’:

List out 3 of your values: i.e. integrity, family, education, prosperity… you can list out more if you’d like!

What is one aspect that you find the most important about museums and collections?

What is a second aspect that you find to be important about museums and collections?

Note: First page of the two-page curation philosophy worksheet geared towards identifying student’s core values and applying those values to specific museum and collection activities and missions. The second page (not included here) was a guided paragraph writing exercise to put student’s thoughts into a full curation philosophy which they can use during job applications.

Assessment of the Course

The course was assessed in multiple formats throughout the semester. During the course, an individual meeting with each student prior to Spring Break provided an outlet to express their thoughts about the course, my teaching style, and to play a role in structuring the remainder of the course. Besides these meetings, anonymous surveys and a final learning portfolio submission aided in updating the course topics as well as provided insight into course improvement for future course offerings.

Anonymous Surveys

Two surveys were implemented, one anonymously in conjunction with the mid-semester individual meetings, and the other IDEA survey hosted by the university at the end of the semester. The first survey was geared towards student involvement with topics so far covered as well as topics students wished were incorporated into the schedule. One topic suggested by students was job opportunities within the field of museum studies. This interest came from students who were not directly involved with museums or interested in museum careers (i.e., dentistry and software development). To address this, I contacted external museum curators and contractors to gain insight into future jobs, and developed a lecture specific to job titles, responsibilities, and current opportunities. Several students who were near graduation appreciated this discussion, as they had not had much career-oriented discussions in other coursework.

The second survey addressed university-specified criteria along with instructor-indicated core learning objectives for the course. These IDEA surveys give the university an idea on how the course addressed thirteen campus-wide generalized objectives. As the instructor, I selected the three most relevant objectives to be weighted more in the final course scores. Gaining basic knowledge (4.3/5), learning to apply course material (4.2/5), and developing specific skills (4.2/5) ranked average to above average compared within the discipline and across the university. I also provided extra written questions concerning the various components of the course and how students felt about course activities, collection visits, and semester projects. Students liked the in-person collection visits (4 of 8 comments), diversity of class discussions (3 of 8 comments), and the ungraded structure of the course (3 of 8 comments).

“I gained a better understanding of the need and goals and ideas of other academic areas on collection. As time goes on, collections are going to become more important to research and grad students need to be aware of the influence.”

Student IDEA survey response

Many students commented that the grant proposal and some discussion topics were completely new to them and that possibly more background was needed to adequately participate. Topics centered on the natural history collections were new to anthropology students, and lectures regarding legal aspects and interpretation were new to natural science students. Since I have a background in each, I tended to jump into these topics without much leadup besides the virtual discussion board. With this, I would add more leading questions within the virtual discussion assignments, specifically leading students to consider multiple angles of a topic instead of asking for their reflections and personal connections. I would also provide additional successful grant proposals which students can read through, potentially adding an activity addressing the components they think worked and didn’t work within a grant.

“Discussions could be challenging but in a good way. They made me think a bit more.”

Student IDEA survey response

“Writing a proposal for a collection [was most difficult]. It was a challenging task, since it was my first time. But I enjoyed it a lot, and I definitely learned how to better utilize the resources around me to fulfill my tasks.”

Student IDEA survey response

Learning Portfolio and Grades

Student assessment with discussions, lecture and collection visit participation, and writing were evaluated through a final individual meeting and a learning portfolio. Learning portfolios are one method which provide an opportunity for students to reflect on their learning progress. This assessment strategy can be applied to any course offering, regardless of discipline, as it promotes writing and self-reflection practice (Blum, 2020, pp. 185). I decided to implement a learning portfolio for students to reflect on the course at the end of the semester. This not only included assessing their personal progress, but also provided an opportunity to propose and defend a final grade which was further discussed in the final individual meeting as part of university requirements (Blum, 2020, pp. 167, 185). Prompts used for this assignment were:

- What were your previous thoughts about collection management?

- Compare and contrast your previous thoughts and how you’ve grown using supporting evidence.

- Provide a grade that you think you deserve based on the supporting evidence and personal growth.

The learning portfolio provided students with an outlet and a way to organize their thoughts centered on museum and collection management. Students had creative liberty to format their learning portfolio how they desired. Most students provided a strictly written, report-like paper, with a few choosing to create multi-paged Canva presentations, one website, and one video. Within their portfolios, students reflected on the course more specifically than what they submitted to the university sponsored course surveys. A few examples below came from the portfolio but were not reflected within the anonymized university surveys.

“As a future science writer, I wanted to develop my skills of scientific writing. I especially saw this in Discussion 7 as we interpreted a specimen in a short skit. This class has shown me how words change how we see an object.”

Junior in Technical Writing/Biology, with reference to the interpretation discussion week

“Other disciplines have their view on collections and their uses… now I can articulate that and possibly assist someone from a different discipline in the future.”

Graduate Student in Anthropology, with reference to the breadth of the course topics

Every student showed improvement in their critical thinking skills and ability to apply theories or lessons from one topic to real life application and problem solving. I initially planned to apply a 100%, or the letter grade of an A, for all students based on their critiques of their work and improvements on their writing. However, some students were highly critical about their learning process. When discussing with students during final individual meetings, students felt that having assignments turned in late was more important to the grade than the actual learning or their explanations and justifications. Some students even proposed lower grades, but when asked to summarize their learning or asked about a course topic, they demonstrated their understanding of content verbally. Those proposed grades were then updated as an agreement between me and the student to reflect this level of learning. After these adjustments, the average final grade suggested by students was 96%, with grades including A, A-, and B.

Future Improvements

Even though this was the inaugural offering for the course, students positively commented on the course structure and content. Many students stated that they appreciated the layout of the course within the online learning management system (Canvas), specifying that having links in multiple places helped them organize their schedules, allowed for reminders, and provided easy access to assignments. The virtual discussions, which consisted of written texts, skit-building exercises, evaluations, and reflections as opposed to academic papers, were appreciated as an introduction to practical applications of museum studies and the course topics. The in-person lecture times, which were one hour and 15 minutes long twice a week in the late afternoon, provided enough time during one session to get through lecture content, small group and full class discussions with time to address questions. As expected, the most liked component of the course was getting behind-the-scenes access and hands-on practical application of caring for collection objects and drawing comparisons between collections with differing mission statements.

There are two instructor areas the students and I identified as needing improvements or changes based on individual student meetings, surveys, and comments made within submitted learning portfolios. As an instructor, I should spend more time emphasizing the structure of the lectures and more often articulate expectations of the course (assignments, learning portfolio), possibly on a weekly or bi-weekly basis. This would remind students in lecture in case they do not visit the specific Canvas pages that detailed how the course was structured. Since I am extremely passionate about the subject, deciding what information to include was difficult. I often planned too much for single lectures. While the basic information was discussed, class discussions sometimes took the full lecture period. It would be ideal to discuss all facets of collection care and maintenance, but too much information created attention fatigue. Instead of trying to accommodate too much information in class, this extra information can be used to start online discussion boards or future think-pair-share exercises. Below are several other suggestions on updating components of the course.

Grant Writing

Students felt that choosing their own grant was a barrier to the project. Instead, having students write for the same grant, preferably focusing on one that is offered by the university, would alleviate this initial stress or apprehension. For example, USU offers both URCO and GRCO (Undergraduate/Graduate Research and Creative Opportunities) grants to fund extra student projects alongside their education. Having a single grant provides students with a consistent set of guidelines and formatting requirements. With the same formatting, everyone can compare their paragraph structures and have more chances to edit similar proposals. An addition to this project would be to encourage students to formally submit these grants with the collection manager. This would provide additional feedback from the grant review process and allow for further work within the museum setting outside of the course.

Learning Portfolio

From the instructor perspective, students did not work on the learning portfolio until the last week of the semester. This made a lot of the portfolios seem rushed or under-developed. While missing and under-developed components were addressed during the final individual meeting, students missed out on deeper reflections. During the semester, assigning sections of the learning portfolio would give time for students to reflect periodically. For example, on the first day of classes, an activity can have students spend 10 minutes answering questions regarding their prior museum studies knowledge and what they hope to learn in the course. Saving their thoughts in a dedicated section within the online learning management system (e.g., Canvas) for their learning portfolio will allow students to have easy access to their prior thinking and expectations for the course. Repeating this reflection in class towards the middle of the course in conjunction with the individual mid-semester meetings and again prior to the last week of classes will allow students to keep track of any perception changes.

Additions to the Course

Self-assessment and self-advocacy (part of Learning Objective #3) were two components that my students and I identified as undeveloped within the course. These two aspects are critical for students to practice. All students had a difficult time assessing their work and relied on me to provide critiques and final assessments. The assessments and advocacy worked into the coursework seemed to be an afterthought for the students, and they indicated in their IDEA end-of-semester surveys that more work in these areas would greatly help with their confidence.

Student’s introduction to self-assessments was originally connected with the survey lecture. The plan was to discuss SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) and SOAR (Strengths, Opportunities, Aspirations, and Results) analyses. Unfortunately, the discussion portion consumed the full lecture time. After class, I created a virtual assignment for students to complete these assessments on their own, using my own mid-semester evaluation as an example (Table 2). Because of this, students did not have direct guidance or in-class practice with completing these assessment forms for themselves. Having a full day to go over the criteria and practice assessing aspects of a student’s work within the course would give them tools and a better understanding of how to self-assess and address obstacles in their learning.

| Helpful | Harmful | |

|---|---|---|

| Internal | Strengths:

|

Weaknesses:

|

| External | Opportunities:

|

Threats:

|

Note: Instructor SWOT Analysis assessing completed instruction and course content during the mid-semester survey and individual student meetings. The objective used for this SWOT Analysis was: Create and lead a course introducing collection material handling on the USU Campus to upper-level and graduate students.

Self-advocacy was also difficult, as apparent in several student’s learning portfolios. As part of their portfolio, students were asked to propose and justify a final grade that would be sent to the university for records. Students tended to give themselves lower grades with limited justification. During individual meetings, however, explanations and justifications were clearly stated by almost all students. Providing additional opportunities for students to practice advocating for themselves throughout the course would be recommended. This could include more one-on-one meetings throughout the semester or having them propose a grade for themselves that is entered in the grade book mid-semester, so they have their own checkpoint for where they stand. It may serve well to make self-advocacy more important to the learning portfolio, such as practicing written and verbal advocacy throughout the semester or on smaller assignments.

Final Thoughts

In all, students who have not participated in museum studies, or who have only had brief introductions without hands-on experience, gained a better understanding of the time, effort, and considerations it takes to properly manage a collection and museum objects during this Collection Material Handling course. Student backgrounds in this course ranged from anthropology, genetics, computer science, dentistry, and technical writing. When asked if this type of course should be offered in the future, all students who completed (n = 11 of 13) the IDEA end-of-semester survey responded with an overwhelming ‘yes’:

“Yes. It is an area of science/humanities that I don’t think many people ever experience or know about. It was incredibly insightful and really expanded my understanding of what both my chosen field and other fields were capable of.”

Student IDEA survey response

“Yes! Most definitely yes. I feel the transdisciplinary aspect of this course makes it more accessible to students outside the field of collection and museum management to get a good introduction.”

Student IDEA survey response

Courses that address the management of museums and collections are few and far between in the United States, mostly contained within specialized disciplines with few opportunities for interdisciplinary students. Courses such as this, which use collection spaces within university settings, have the possibility of reducing educational and interest barriers between the humanities, arts, and sciences. I hope the examples provided here can be implemented within established courses or as full course offerings at USU and beyond.

References

Biglan, A. (1973). The characteristics of subject matter in different academic areas. Journal of applied Psychology, 57(3), 195.

Blum, S (ed). (2020). Ungrading: Why rating students undermines learning (and what to do instead). West Virginia University Press.

Bruner, J. S. (1996). The culture of education. Harvard University Press.

Bunce, D. M., Flens, E. A., & Neiles, K. Y. (2010). How long can students pay attention in class? A study of student attention decline using clickers. Journals of Chemical Education, 87(12), 1438–1443. https://doi.org/10.1021/ed100409p.

Cals, J. W. L., & Kotz, D. (2013). Effective writing and publishing scientific papers, part III: Introduction. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 66(7), 702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.01.004.

Carlson, M. M. (2002). Winning grants step by step. (2nd edition). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Center for Rural Health. (2022, October 15). “Grant Writing Worksheets”. Grant Writing. https://ruralhealth.und.edu/grant-writing/worksheets.

Curry, S., Bean, M., Brown, A. C., Harris, S., Kirschner, N., Waller, J., & Young, H. (2022). Implications and considerations for cross listing courses. Academic Senate for California Community College. https://www.asccc.org/content/implications-and-considerations-cross-listing-courses.

DaRosa, D. A., Kolm, P., Follmer, H. C., Pemberton, L. B., Paerce, W. H., & Leapman, S. (1991). Evaluating the effectiveness of the lecture versus independent study. Evaluation and Program Planning, 14, 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/0149-7189(91)90048-L.

Hart, L. (1991). The “brain” concept of learning. The Brain Based Education Networker, 3(2), 1-3.

Hitlin, S. (2003). Values as the core of personal identify: Drawing links between two theories of self. Social Psychology Quarterly, 66(2), 118–137.

Kaplan, R., & Kaplan., S. (1989). The experience of nature: A psychological perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Katz, P. M., & Merritt, E. E. (Eds.). (2010). Museum financial information 2009. American Association of Museums.

Landers, R. N., Bauer, K. N., Callan, R. C., & Armstrong, M. B. (2015). Psychological Theory and the Gamification of Learning. In: Reiners, T., Wood, L. (eds) Gamification in Education and Business. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-10208-5_9

Lang, J. M. (2016). Small Teaching. Jossey-Bass A Wiley Brand.

Lang, J. M. (2020). Distracted. Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Lee, K. E., Williams, K. J. H., Sargent, L. D., Williams, N. S. G., & Johnson, K. A. (2015). 40-second green roof views sustain attention: The role of micro-breaks in attention restoration. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 42, 182–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2015.04.003.

Macalester College (2023). Cross-listing guide. Macalester College. https://www.macalester.edu/registrar/services/crosslisting/.

Marcus, J., & Roy, J. (2019). In search of sustainable behaviour: The role of core values and personality traits. Journal of Business Ethics, 158, 63–79.

Markant, D. B., Ruggeri, A., Gureckis, T. M., & Xu. F. (2016). Enhanced memory as a common effect of active learning. International Mind, Brain, and Education Society, 10(3), 142–152. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/mbe.12117.

Marstine, J. (2005). Introduction. In J. Marstine (Ed.) New Museum Theory and Practice: An Introduction. Blackwell Publishing.

National Science Foundation. (2023). Program Solicitation. Infrastructure Capacity for Biological Research. https://www.nsf.gov/pubs/2023/nsf23580/nsf23580.htm.

Nelson, L. P., & Crow, M. L. (2014). Do active-learning strategies improve students’ critical thinking? Higher Education Studies, 4(2), 77–90. https://doi.org/10.5539/hes.v4n2p77.

Neumann, R. (2001). Disciplinary differences and university teaching. Studies in Higher Education, 26(2), 135–146.

Rice, G. T. 2018. Hitting pause: 65 lecture breaks to refresh and reinforce learning. Stylus Publishing, LLC.

Robert, M. Jr., and Neff. J. (2017). How senior entomologists can be involved in the annual meeting: organization and the coming together of a large event [abstract]. Entomological Society of America Annual Meeting. Denver, CO., United States of America. https://www.ars.usda.gov/research/publications/publication/?seqNo115=347020.

Sarnecka, B. W. (2021). The writing workshop: Write more, write better, be happier in academia (2nd ed.). Author. https://osf.io/5qcdh/.

Schwartz, S. H. (1992). Universals in the content and structure of values: Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M.P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Academic Press.

Silverman, L. H. (1997). Personalizing the past. Journal of Interpretation Research, 2(1), 1–12.

Wiggins, G., & McTighe, J. (2005). Understanding by Design (2nd ed.). Pearson Publishing.

Appendix A

Course syllabus for Collection Material Handling (ANTH 5800/6800, BIOL 4750/6750, WILD 4950/6900. Three pages include the introduction with course activities, a full schedule, and university policies.

Appendix B

Details on the timeline and activities completed during the semester for the student’s grant proposal semester project. Backward design was applied to the grant writing process to help students focus on addressing the needs of the selected collection. Therefore, sections were introduced and addressed opposite of how they are generally ordered in a final grant submission.

Week 1–4: Deciding On A Collection and Topic

The project was introduced during the first week, and students had three weeks to decide which collection they wanted to work with and what general topic they wanted to address in their grant. Because there were diverse interests amongst the students, there were also diverse grant topics proposed. Topics included funding a traveling exhibit for the mammal collection, purchasing insect pinning supplies for the entomology research collection to address backlog specimens, purchasing time with a CT-scanner to investigate a mummy in the anthropology collection, and hiring undergraduate technicians to photograph the jars in the herpetology research collection. All topics addressed a need for the collection, spanning between research and education.

Week 5: Expected Outcomes

Students were then asked what they and the collection would hope to gain from receiving the grant. I provided extensive feedback on their Expected Outcomes submissions. Most students during this first portion of the project were hesitant to write about concrete outcomes, using words like ‘may affect’ and ‘I hope this PROJECT will benefit the museum’. I encouraged them to hypothesize more concrete and directional outcomes, such as ‘to positively change people’s perceptions about TOPIC and their role in ecosystem function and human interactions’. Several students made an effort to resubmit updated expected outcomes for additional feedback before continuing onto developing the methods section.

Week 6–8: Materials and Methods

From there, students spent three weeks deciding exactly how they would design or implement the project to reach those desired expected outcomes. I provided several prompts for students to consider when creating their Materials and Methods section of the grant. These prompts included identifying materials and equipment, details about the university’s hiring processes, and a monetary breakdown of a budget with justifications. I provided two of my own examples of a Materials and Methods sections from submitted grants; one of which was accepted for a molecular study on wasps, another was rejected for an exhibition about wasps for K-6 students. Students then had an opportunity to read through both an awarded and rejected (with reviewer feedback) proposals from my past research. Providing these examples for students helped them understand the level of detail needed within the proposal to make it competitive and compelling.

I again provided extensive feedback about each student’s methods section, making sure to point out portions that did or did not address their expected outcomes. For example, one proposal’s outcome was to increase visitation rates to a museum using a campus scavenger hunt. The methods only included information about prizes for visitors upon completing the scavenger hunt and visiting the museum. My comments included identifying specific materials needed for satellite exhibits around campus and considerations for display cases depending on location.

At the end of this section, I received comments from students about my feedback. Several students indicated that they were beginning to learn just how much thought and effort it requires to compose a thorough methods section.

Week 9–12: Introduction and Background

Once the expected outcomes and methods were solidified, another three weeks allowed students to write an introduction which encompassed the background, the needs, and broader impacts of the collection. Several of these collections have a long history of research and outreach, such as the entomology collection which started in the early 1900’s. Setting the stage for requesting funding through these grant proposals often focused on the impacts the collection has on the USU and broader communities. My comments included suggestions on rearranging paragraphs to create the ‘funnel’ effect of writing; starting with the broader background, and slowly working through progressively narrowing topics to reach the final statement of purpose for the grant. This funnel strategy is often used for the introduction of other scientific writing such as journal articles (Cals & Kotz, 2013).

Week 13–14: Peer Reviews

After all feedback was provided for each section, students submitted a draft of their full proposal via Canvas. I set this assignment up so that each proposal was then reviewed by one other peer. This allowed other students in the class to read through another proposal, collecting ideas and sharing their thoughts on possible edits.

The peer editing and commenting process continued with a class activity based on The Writing Workshop book by Dr. Barbara W. Sarnecka (2021, pp 19). I divided everyone’s introductions between groups of three or four students. We spent one lecture period live editing those introductions in Google Docs. Each introduction had student’s names removed, and each group live-suggested (ensuring everyone was in Suggestion mode, and not Editing mode) other student’s introduction; no group member had to comment on their own submission. I jumped between files during this time to also provide feedback. This was the first time any of the students did any type of live-suggesting, and it took a few minutes for them to become comfortable enough to provide suggestions.

At first the suggestions were generic and non-specific statements like ‘clarify this’ or ‘I don’t understand this’. I stopped the class to explain how to provide critiques and suggestions such as ‘identify why the statement isn’t clear and provide a suggested restructured or revised sentence’. Working through examples of and practicing specific critiques would have aided in this portion of the grant writing process. Even with the fast explanation, students started suggesting wording, sentence structure, and sentence organization changes.

Week 15: Lightning Presentations and Final Submissions

Like effective writing, public speaking is an important soft skill that requires practice for confidence-building. Lightning presentations are also becoming an important outlet for research in national meetings such as the Lightning Bug Presentation competition hosted by the annual Entomological Society of America meeting (Robert and Neff, 2017). Getting a project proposal or research results across verbally, like grant writing, is not often practiced within coursework.

At the end of the semester, students had to pitch their grant proposal to the class. Each presentation was limited to three to five minutes with up to two PowerPoint slides. Three additional minutes were used to discuss the presentation and the project as a class. After additional comments from peers during these lightning presentations, students had an additional week to finalize their proposal and submit the grant via Canvas. I took additional time to make further comments on the written proposals, which were discussed with the student during their final individual meetings during finals week.