Reinvigorating the Post-COVID Gen Z English Major

Gaby Bedetti, Ph.D.

Abstract

The decline in English majors has energized instructors to upskill for the post-COVID Gen Z student. Toward that end, this small-scale (n=20), one-semester study of an upper-division literature class identifies the preferred learning styles of English majors at a public comprehensive regional university in Kentucky. The participants represent national English major demographics. The research methods are quantitative and qualitative. Eight figures and an appendix are included. Three guidelines emerge for responding to the needs of Gen Z students: 1) keep communication brief, 2) co-create, and 3) interact in-person. The findings about English major learning preferences uphold cross-disciplinary research on active learning in the post-COVID era by indicating ways our teaching styles can keep pace with the needs of our changing majors. In addition to the participants’ experience in the investigator’s course, the survey collects their experience of teaching styles in six core courses in the English major. One drawback of the study is the small participant sampling. Future studies might investigate the difference between students’ preferred learning styles and instructors’ actual teaching styles. Building the English major back better calls for putting accepted theory into reskilled practices.

Keywords: students, English major, learning styles, course format, Gen Z, post-COVID

Introduction

Anyone teaching in a college English Department is keenly aware of “the dwindling number of English majors” (Parry, 2016, para. 26). From 2012 to May 2017, English degrees fell 17 percent, though communication degrees increased 8 percent (American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2021). Although English departments may survive to support the literacy of students in other majors, the viability of English as a major course of study is precarious (Hiner, 2012; Kalata, 2016, p. 54). According to two professors at University of South Carolina, Beaufort, “The BA in English faces significant challenges—most notably, since 2012, the developing risk of extinction” (Swofford & Kilgore, 2020, p. 45). Heller’s claim in The New Yorker on the death of the English major (2023), Walther’s probe in The New York Times on the death of poetry (2022), followed by his “second inquest” (2023), and Scott’s essay on the reading crisis (2023) give voice to an anxiety shared among academics in the humanities across the country (Letters, 2023; The Mail, 2023). The expanding conversation is leading academics to retool their instruction for the new generation. Nationwide English faculties at regional comprehensive universities like mine are rallying. The declining enrollment, with its significant impact on education, creates an opportunity for English departments to rebuild the major for a post-COVID society (Zhao, 2022). A quantitative and qualitative research project, the current study seeks to learn what classroom adjustments resist the trend away from English, particularly away from literature. In addition to collecting the study participants’ learning experience in my course, the study collects their experience in six core courses in the English major. Like other research on the scholarship of teaching and learning that “remain in large part small-scale, short-term, and local in orientation (Harland 2016; Tight 2018; How 2020)” (Børte, 2023, p. 599), a drawback of this study is the small participant sampling.

Individual instructors have been finding ways to draw students back to lower-division introductory literature surveys by shifting course outcomes away from the acquisition of content and toward the development of skills (Kalata, 2016). Today’s students appreciate the shift, as illustrated by Heller’s citation of a Harvard history-and-literature major claiming that in his humanities classes, he felt less like a student absorbing information and more like a young thinker (2023). By serving today’s generation, the English Department may “no longer see itself as part of the Humboldtian goal of educating younger citizens for cultural engagement, but rather one that sees itself as creating workers for a society organized around industry, corporate entities that form the backbone of the ‘culture industry’” (Trivedi, 2023, p. 95). To see the work of the humanities as a cultural industry in support of an industrial one requires curricular innovation that appeals to Gen Z’s valued areas of personalization, technology, and outcomes (Johnson & Sveen, 2020). Not content to watch new degree programs claim the versatility ascribed to a degree in English (Phillips & Sontheimer, 2023), English Departments are increasingly positioning themselves to emphasize professional development in addition to their existing focus on cultural development.

Such a shift begins at a grassroots level with individual instructors. My research supplements other studies designing ideal learning on campus after the COVID-19 pandemic. The current study involves surveying English majors in an upper-division course comprised entirely of English majors. To engage learners as partners of change and owners of their learning, I collected student opinions about literature course learning styles. My purpose was to engage students by identifying Generation Z (those born between 1995 and 2012) preferred learning styles. I wanted my English Department to build the major back better by examining how today’s students learn. A postscript to the Modern Language Association’s (MLA) 1990 Survey of Upper-Division Courses, as reported by Huber (1992), the MLA’s study—unfortunately the most recent national survey of upper-division English courses available—comprehensively examines the literature classroom. Like Buchanan (2016), I wondered whether the English Education majors in my upper-division courses, for example, are “encountering models of teaching in literature classes that undermine what they are learning in methods courses” (p. 79). Recent anthologies have collected various pedagogies for the major (Hewings et al., 2016; Lang et al., 2016; Ortmann et al., 2023). To build my pedagogy firsthand from Gen Z responses, I surveyed English majors over the course of a semester about their preferences and the pedagogical approaches they had experienced in upper-division courses at my institution. My aim was to supplement the reports from the MLA as reported in Huber (1992), Houston (2001), and the MLA Teagle Foundation Working Group (2009) with a field report from my classroom and department. I wanted to listen to my students’ preferences for learning. By following Houston’s recommendation that “faculty members make the rationales behind their pedagogical choices visible in their classrooms” (2001, p. 235), I hoped to make my instruction more intentional.

As an instructor, I often encounter models of teaching when I take my classes for library instruction. Exemplars of change, the librarians at my institution reconcile their library orientation with who and where Generation Z post-COVID English majors are by having students work in teams, use cellphones to document their discovery, and report back to the whole class, while the librarian simply bookends their discovery with a ten-minute introduction and Q&A. Because these digital natives have never known a world without the Internet, smartphones, and iPads, librarians have incorporated technology into their library orientations, deftly matching teaching methods to students’ learning preferences (Napier et al., 2018). Caring what our students care about involves stretching our pedagogical imagination and reconciling course materials with what they care about (Gilbert, 2021). English instructors are also developing teaching practices that address their students’ learning styles and cultivate their marketable critical thinking and communication skills. Thus, this study operates within a three-part historical context:

- the Gen Z-focused iterations of the active learning Bonwell and Eisen introduced in 1990 (Gilbert, 2021; Gilbert et al., 2022; Helaluddin et al., 2023; Johnson & Sveen, 2020; Whitehead, 2023),

- the lessons learned during COVID-19 (Bates, 2023; Carillo, 2023; Farney, 2023; Greensmith et al., 2023; Munro, 2022; Zhao, 2022) and

- the conversations in the public square on the death of the English major (Heller, 2022), poetry (Walther, 2022, 2023), and reading itself (Scott, 2023).

To augment our teaching practices in upper-division literature courses for the new economy calls for a continuing questioning of our English majors. As one respondent to Heller’s article writes, “If English departments spent less time lamenting the end of an era and more time engaging their students in a serious conversation, we’d find a wealth of fresh perspectives” (Letters, 2023, para. 5).

Literature Review

Not much has changed since Corrigan (2017) reported that pedagogical scholarship within literary studies is eclipsed by pedagogical scholarship within writing studies. The need for and relevance of a study of English majors’ learning styles comes from the “yawning gap [in pedagogy] between writing studies and literary studies” (p. 550). Despite the small scale of my study, it attempts to fill that gap in literature courses. Richardson and Kring (1997) conducted a study comparable to this one, also at a medium size, regional state university. Whereas their study’s participants were students in beginning as well as upper-level English courses, all the participants in my study had a declared English major. The 1997 study by Richardson and Kring revealed that students “overwhelmingly preferred lectures with an additional element such as voluntary participation, demonstrations, or student discussion groups” in contrast to professor-assisted class discussion. Second, it found that women students liked a more interactive approach to teaching, analogous to the 1990 MLA finding about upper-division faculty respondents, indicating that women devoted less time to lecturing and more time to in-class discussion than other study participants (Huber, 1992, p. 51). Finally, Richardson and Kring found that students with the highest GPAs overwhelmingly preferred professor-assisted class discussion, which the authors conjectured may make this interactive teaching style the most effective for higher-ability students. These conclusions about students in all English courses appear to reinforce the MLA’s earlier finding of traditional course format.

Unfortunately, studies of upper-division literature courses as a unit are even fewer than studies of introductory courses, validating the belief that we are not concerned enough with how we teach literature to our majors (Buchanan, 2016, p. 79). Almost 80 percent of my department’s undergraduate course offerings fulfill the university’s arts and humanities requirements, supporting majors across the institution with courses in reading, writing, and research. However, as bachelor’s degrees awarded nationally have increased by 34 percent, the English major has taken a precipitous downward turn (Laurence, 2017). While the English teacher shortage has reached a crisis point, the employment need for writers and authors is projected to grow 8 percent from 2016 to 2026 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2023).

Seven years before the study by Richardson and Kring (1997), the report prepared by the MLA’s director of research based on the organization’s 1990 study provided the most comprehensive data available on the teaching and learning in the English major. Two of Huber’s (1992) findings apply. First, she found that instructors devoted an equal amount of class time in upper-division literature courses to lecture and discussion. Second, she found that instructors who had received their highest degree within the ten years prior to the survey devoted more time to discussion than instructors who had received their highest degree more than ten years before the survey. The latter finding anticipated a shift away from lecture that has since become more firmly rooted—in theory, if not universally in practice. Following the MLA’s findings on theoretical approaches, educational goals, and course content, the 1990 Survey analyzed course format. The report’s final section is titled “Traditional Texts and Practices Remain in Place.” The report includes the following specific findings:

- There is little evidence…that English faculty members have jettisoned traditional texts and teaching methods in their upper-division literature courses.

- The great majority of respondents subscribe to traditional educational goals for their courses. These aims revolve around providing students with the historical and intellectual background needed to understand the primary texts they are assigned and helping them to appreciate the merits of these texts.

- The teaching formats respondents use in their courses are conventional; almost all respondents’ classes consist of some combination of formal lecture and informal class discussion. (Huber, 1992, pp. 50-53)

To establish the cultural context at the time, Huber begins her “Findings” by explaining why the 1990 survey followed so soon after the MLA’s similar 1984-85 survey. The earlier study found that “courses are added to expand the curriculum, not to replace traditional offerings, which remain in place as core requirements for the English major” (Huber and Laurence, 1989, p. 43). Because these findings were “not in keeping with frequently heard claims of widespread change in the English curriculum” (Huber, 1992, p. 36), the MLA staff members decided to follow up with the 1990 survey. Thus, Huber’s findings served to clear up the discrepancy about whether there had been widespread curricular change, confirming that in the content of courses and the pedagogical approaches of faculty members, institutions had preserved the English major. The MLA saw stability and continuity in the texts that continued to make up the core of literature courses. However, despite the late twentieth-century battle of the books debated by Greenblatt (1992) and others, preserving traditional course format (by contrast to preserving traditional texts) in the literature classroom may not be the best way to attract Generation Z students to the major.

For literary study to be a viable major for our students, English literature instructors have made an effort to evolve their teaching styles. Thirty years after the 1990 MLA study, I conducted a study of the literature learning styles and course format of my classroom and my department. Whereas the Modern Language Association’s questionnaire had over five hundred faculty respondents from within an organization with 25,000 members, this study relies on the data from twenty English majors enrolled in my upper-division literature course in an institution of 18,000 students. Unlike the faculty in the Modern Language Association’s study who completed a questionnaire about their teaching style, the students in my study completed a questionnaire about their learning style. The data gathered from students in the current study complements the MLA study data in that the students’ perceptions of teaching styles may differ from their instructors’ perception of teaching styles.

Research Design

The explicit purpose of the current study was to identify the preferred learning styles of Z Generation English majors in a literature course. At my institution, the core literature courses for the major (whether a student’s concentration is Literature, English Teaching, Creative Writing, or Technical Writing) are Principles of Literary Study, American Literature I, American Literature II, English Literature I, English Literature II, and Shakespeare. Given my observations of today’s students, I posited that interactive learners absorb more than solitary learners do, and specifically, that participants who enjoy discussing their experience of the assigned reading learn more than students who prefer listening to the instructor lecture about the reading.

To evaluate the hypothesis, I designed the course to include a variety of brief in- and out-of-class solitary and interactive activities (Bedetti, 2017). Pre-class solitary activities included submitting a five-question online reading quiz and reviewing the correct answers, preparing a five-minute cultural context presentation, posting an open-ended response to the reading, and composing a creative response. The in-class solitary activity was listening to the instructor’s mini-lecture, defined as the instructor talking without interruption for about ten minutes. The pre-class interactive activities included replying to participants’ responses to the reading and reading responses to one’s own post, as well as replying to participants’ responses to the creative task and reading responses to one’s own creative task. The in-class interactive activities included discussing everyone’s response to the reading assignment.

After receiving my institution’s IRB Exemption Certification, IRB Approval Notification Protocol #1346, Student Informed Consent Form, I designed my questionnaire to measure the study participants’ preferences in activities, learning styles, and course format (Appendix A).

Methods

Participants

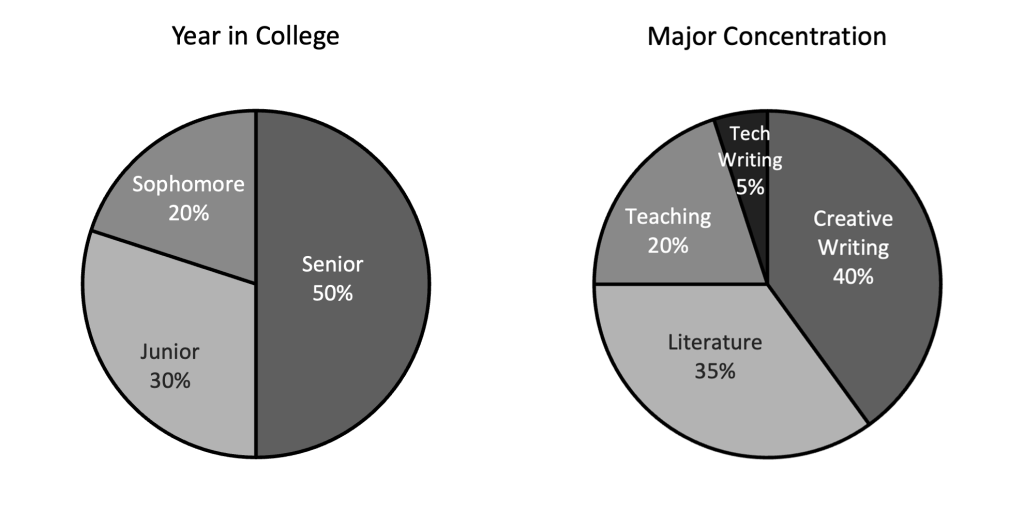

The group studied was a cameo of national English major demographics. The twenty participants represented the varied options at our comprehensive regional university, which requires a minimum ACT of 18 for full admission. Figure 1, showing the participants’ year in college, indicates that most students were well along in their courses for the major, with the largest population being seniors, followed by juniors and sophomores. Since the English major curriculum guide recommends students enroll in English Literature II in the last semester of their senior year, the largest percentage of the group were predictably seniors (40 percent). As a result, the largest group of students had completed the other core upper-division literature courses. The group was also representative of the gender distribution of degrees in English since the late 1960s, as students filled out a survey indicating there were fourteen female participants (70 percent) and six male participants (30 percent), with no students indicating a non-binary gender identity. The gender distribution for English majors appears largely unchanged from what it has been since the mid-sixties (Schramm et al., 2003, p. 90). One student was African American (5 percent), which is characteristic of the racial/ethnic distribution of degrees in English (American Academy of Arts and Sciences, 2019). Finally, one student was nontraditional (5 percent), defined as over the age of twenty-four.

Moreover, Figure 1 regarding participants’ major concentrations indicates that this group represented national trends (Marx & Cooper, 2020). According to the ADE Ad Hoc Committee on the English Major (2018, p. 38), in the various tracks departments offer for majors, only in creative writing were departments more likely to report enrollments that increased. Literature has experienced the highest decrease (74 percent), followed by English education (69 percent). Given the upsurge in creative and technical writing, it is not surprising that 40 percent had a concentration in writing rather than literature. At the University of Missouri Columbia, one of the most comprehensive schools in the United States, the trend toward writing is even more pronounced than in my study participants: Sixty percent of their majors at the time named creative writing as their primary emphasis (Read, 2019, p. 15). At my institution, teaching majors tend to select American rather than English literature to fulfill their literature requirements, so the 20 percent majoring in English Teaching was unsurprising. In sum, the most recent data sets indicate that this study’s participants approximate the distribution of today’s English majors with regard to gender, race, and major concentration.

Procedures

The course selected to study the learning styles of English majors was a survey of English literature since the late 1700s. On the first day of class, after reviewing the course syllabus and the study, students received an Informed Consent Form, which described the study, stipulated that participation was voluntary, and assured their anonymity.

My research methods were both quantitative and qualitative. Within a week of completing the study of a literary period, participants completed an online questionnaire reflecting on the recent unit. The first six questions invited participants to rank their enjoyment and learning through activities on a Likert-like survey that enabled me to measure participants’ preferred learning styles. The second six were open-ended questions that invited students to comment on their learning styles and the various class activities, as well as to estimate the ratio of class time devoted to lecture and discussion in the six core upper-division literature courses (Appendix).

To measure student learning, I used participants’ scores on the unit tests, which weighed twenty-five objective questions and an essay equally. The open-ended essay allowed students agency in the construction of their thesis about the period and in the interpretive processes that they brought to bear. While the three unit tests combined were only weighted 30 percent in the course grade, this closure task to each unit provided a quantitative way of assessing learning progress.

At the end of the semester, I printed the unidentified questionnaires and entered the data into Excel. Using separate graphs for each unit, I ranked participants for Unit I, II, and III from lowest to highest test score recipient. To determine the role of their preference for lecture and discussion, I included the learner’s rating for enjoying lecture and enjoying discussion. I then examined whether participants’ learning preferences related to their assessed learning.

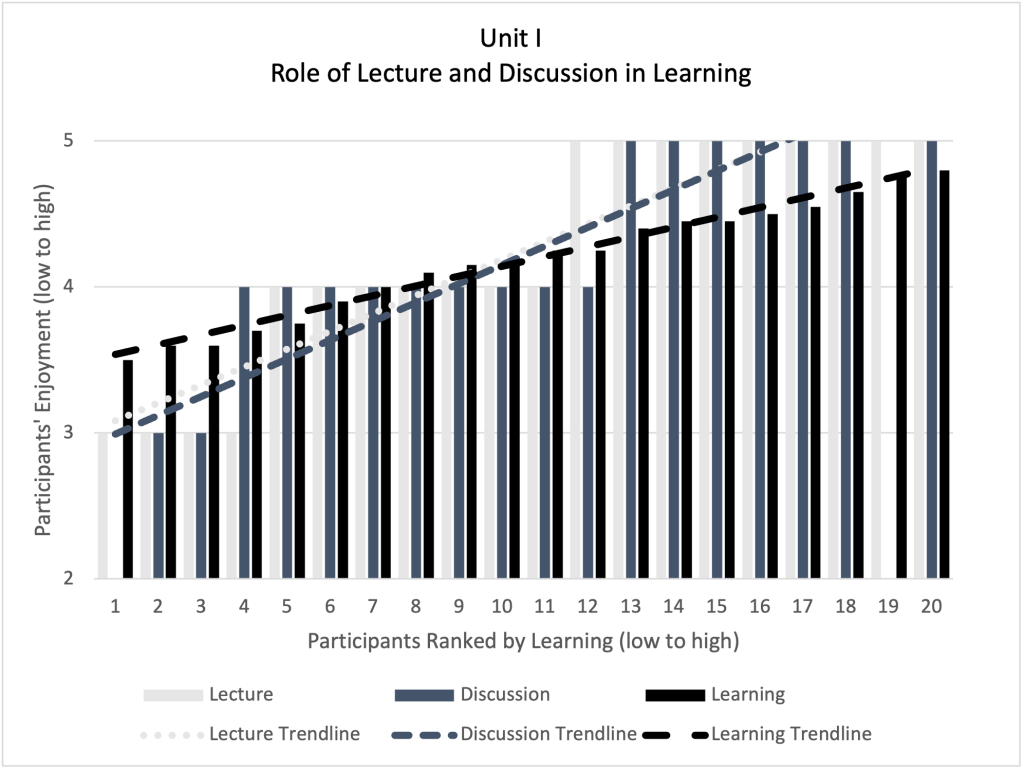

The data from the first unit survey shows a correlation between enjoying discussion and performing well on the test. In Figure 2, the twenty participants are ranked from lowest to highest, according to their unit test score. As the nearly identical trendlines for lecture and discussion indicate, participants enjoyed listening to lecture and participating in discussion in equal measure. The learning participants demonstrated on the first test nearly matched the degree to which they enjoyed discussion; in other words, the more a student enjoyed class discussion, the better the student performed on the assessment.

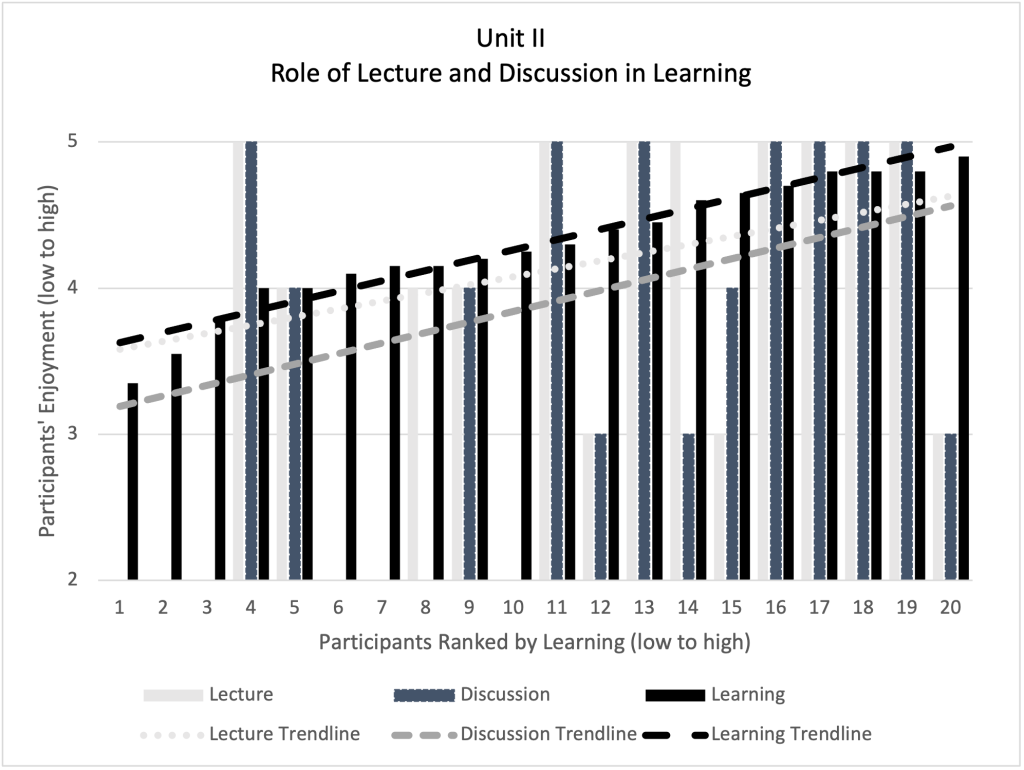

Even more noticeably, the data for the second survey reveals a direct correlation between how highly a student ranked their enjoyment of class discussion and how highly they scored on the test. The discussion and learning trendlines shown in Figure 3 are parallel rising trendlines. Conversely, the lecture trendline shows that participants who indicated greater enjoyment for lecture scored slightly lower on the unit test than those who preferred discussion. Gaps in data reflect students who did not complete or partially completed Survey 2.

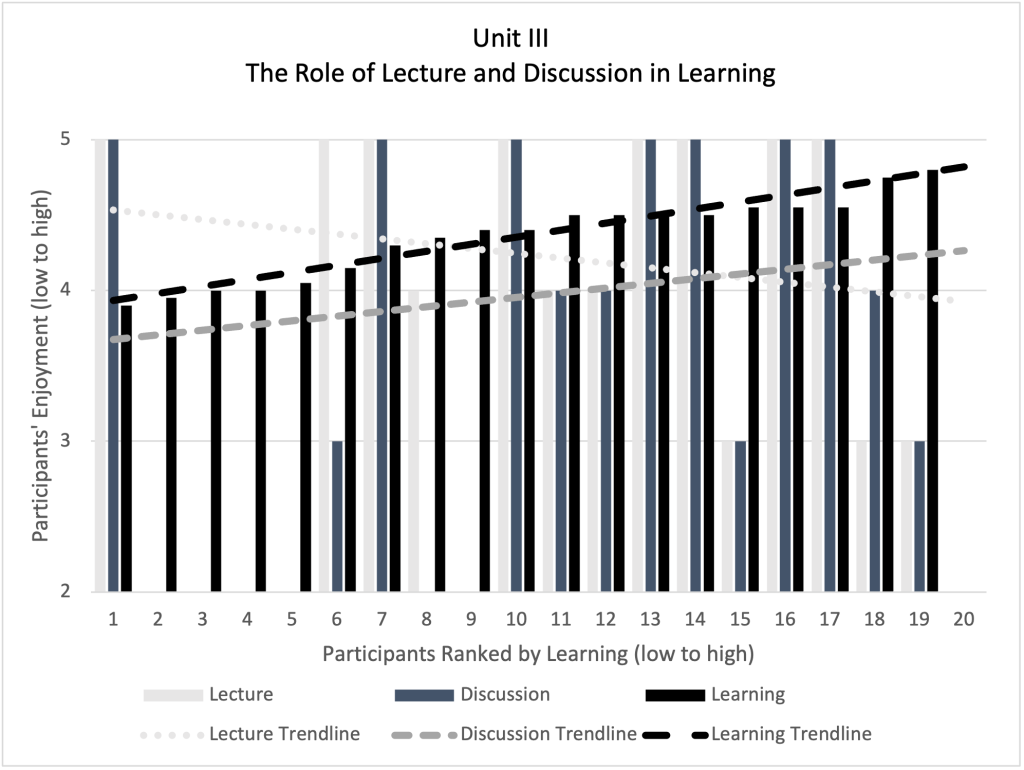

Like the data from the first two surveys, the final unit data also shows a direct correlation between discussion and learning. In fact, Figure 4 shows that while discussion directly linked to learning, the falling lecture trendline indicates that lecture was in inverse relation to learning. The data gaps in the graph reflect students who did not complete or partially completed Survey 3. The absence of data for participant 20 indicates a student who withdrew from the course; the student was minimally involved in course activities, not only in class discussion but also in the pre-class online activities.

Findings

Interaction Accelerated Learning

At multiple points during the semester, the study shows a consistent correlation between participants’ enjoyment of class discussion and learning (Figures 2, 3, and 4). Participants’ open-ended comments support these quantitative results. In response to the question, “What activity in the unit has helped the most to make you more articulate?” participants mentioned class discussion nearly as much as any other activity: six on Survey 1, four on Survey 2, and five on Survey 3. However, participants singled out pre-class online discussion slightly more often: six times on Survey 1, five times on Survey 2, and five times on Survey 3. Here is a sampling of their comments about interactive activities:

- I have learned how to discuss literature better in the context of other people’s opinions.

- Thinking about the literature to make online posts and elaborating on them in class have made me more articulate–one of my favorite parts of this class!

- I think that this class setup is so enjoyable. Everyone has the room to explain their thoughts and feelings about the text in a judgment-free way, via whole-class discussions as well as Blackboard discussion forums. (Survey 3)

Preference for Interaction Increased

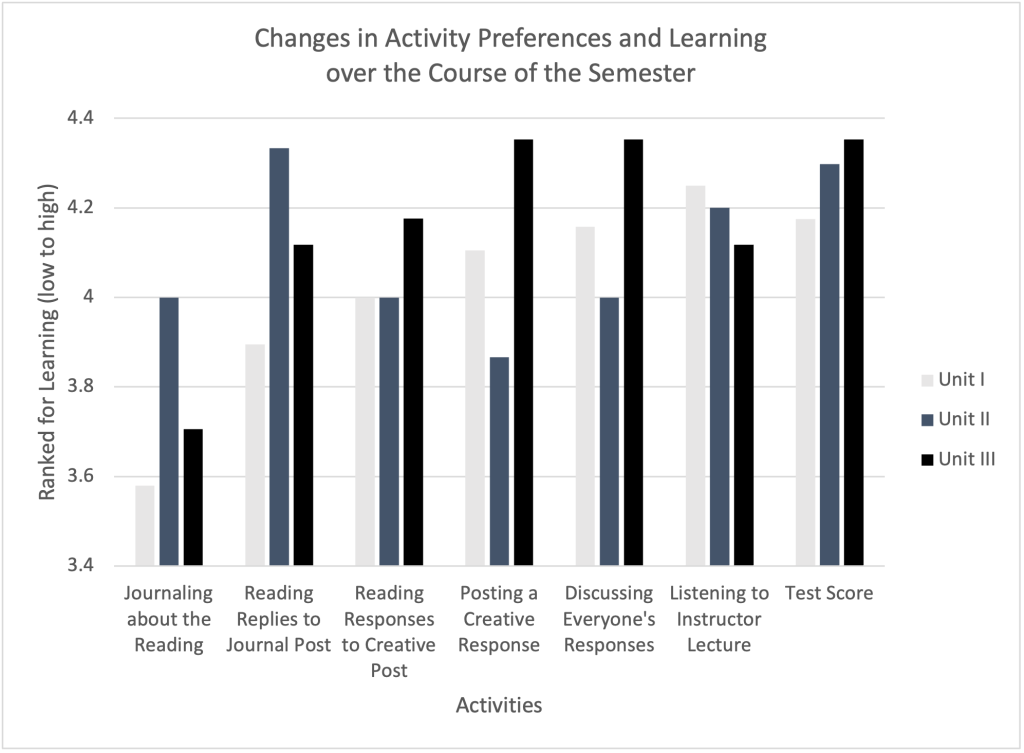

In addition to individual participant results, the data yielded group findings. The last three sets of columns of Figure 5 suggest that the group transformed its learning style during the study.

As the group’s enjoyment of discussion rose over time, their learning increased. To confirm, Figure 5 also shows that as the group’s enjoyment of passive listening fell, their learning rose.

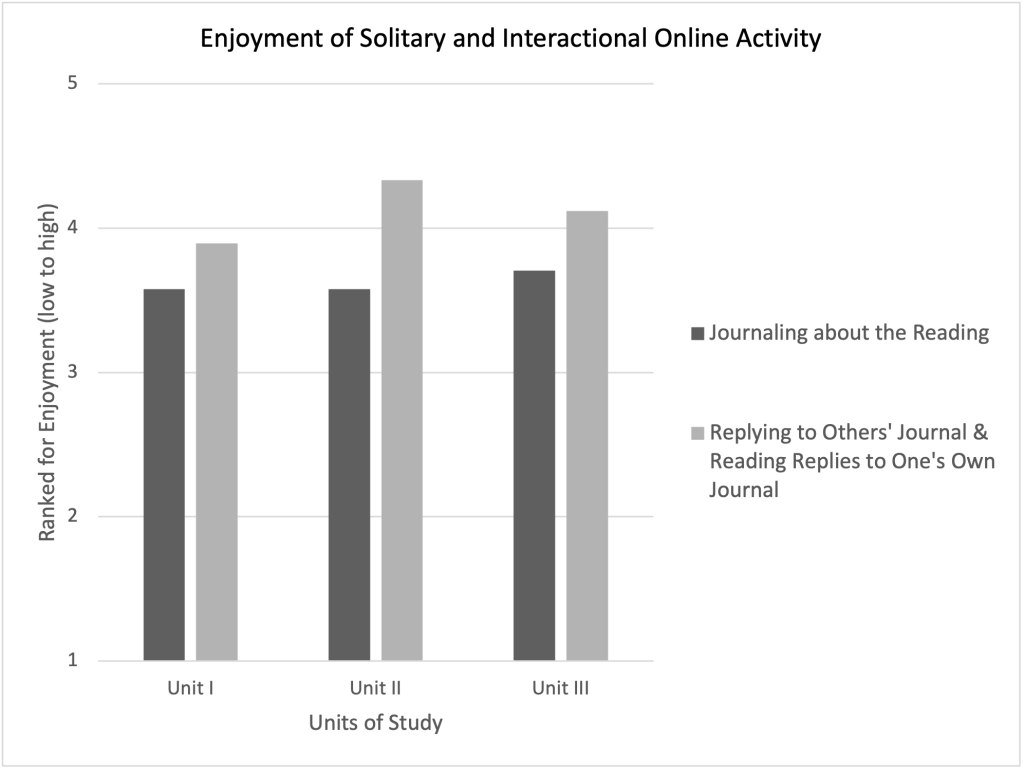

Students enjoyed discussing more than listening to lecture; by contrast, they did not enjoy posting their pre-class response nearly as much as sharing their comments in class. According to Figure 5, in the context of the other activities, the solitary composing of journal responses received the lowest ratings among all activities. In fact, Figure 6 reveals that participants ranked composing their open-ended response to the reading significantly lower—a full point lower—than interacting with each other by reading their classmates’ posts, replying to two classmates, and reading replies to their own post. In short, students preferred learning together.

The survey’s open-ended questions, however, yielded comments that acknowledged the value of their solitary responses to the reading. In answer to the question, “What activity in the course has helped make you more articulate?” one student answered, “definitely” in the discussion board posts. She amplified:

I sometimes struggle a bit more to articulate my thoughts about a reading in class when I’m on the spot, but when I can sit down and write a discussion board about a reading it gives me time to stop and really reflect on what I’ve read and what I think about it. That process really helps me learn and remember the material, which has helped me become more articulate in class because I’ve spent more time really thinking about the reading. (Survey 2)

Thus, while solitary articulation ranked low on the enjoyment scale overall, more than one participant attested to the value of posting to forums; specifically, what also helped was “the fact that you can’t see anyone’s posts before you do your own” (Survey 1). Figure 6 shows how participants favored even asynchronous online interaction over solitary reflective posting. While students recognized that, however arduous, they needed to reflect and articulate on their own before coming together online or in class, they enjoyed leaving the traditional ivory tower.

While I did not define or discuss what it means to be articulate, these comments suggest that they recognized that being able to articulate their thoughts marked students’ academic socialization into the class as a learning environment (Bedetti, 2017a). When they were able to situate their discourse in the larger academic conversation by externalizing their thoughts in debate with others, their enjoyment of a mutual social presence enhanced learning.

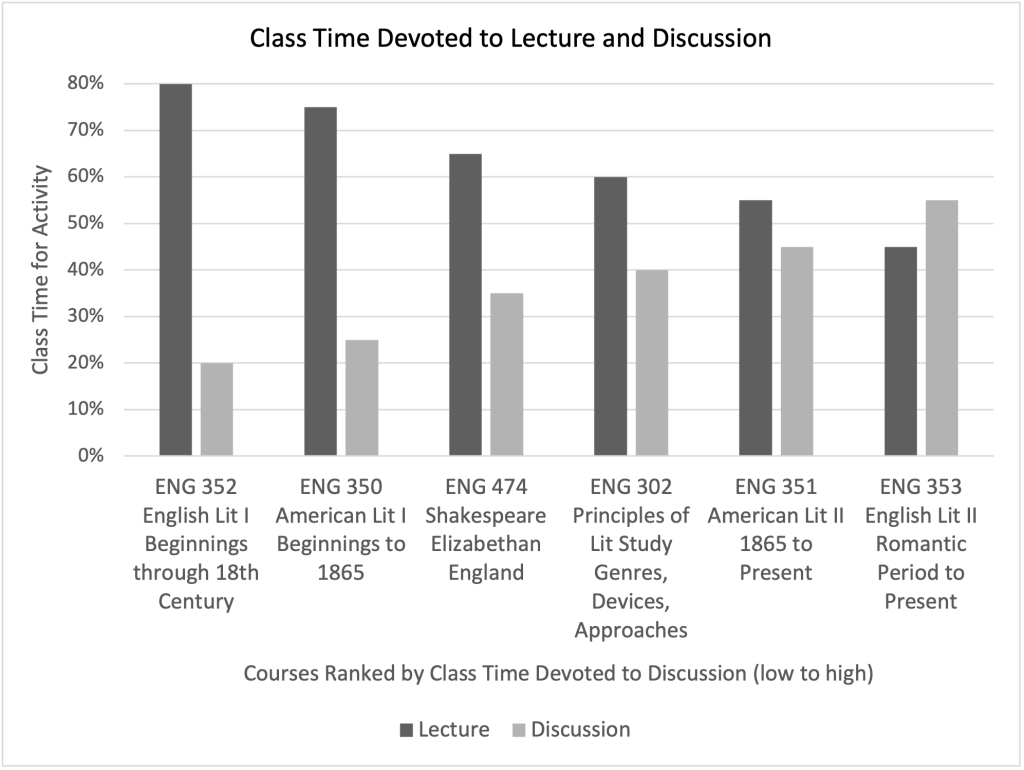

Traditional Course Format Persists

To contextualize the study of learning styles in one course, participants estimated the use of class time in all the core upper-division courses they had completed. Figure 7 ranks the six core literature courses for the major according to class time devoted to discussion, organized from low to high. The data reveals that the three courses with a higher percentage of class time devoted to discussion deal with literature written in the last two centuries, whereas the three ranking relatively lower in-class time devoted to discussion deal with older literature. The catalogue description of four of these courses begins, “A study of selected works by representative authors, reflecting the chronological development of,” followed by the literary historical period shown in Figure 7. A fifth course description references the Elizabethan period (1558-1603). According to the amount of class time devoted to lecture and discussion, lecture appears to prevail in almost all upper-division literature courses in the major.

Discussion

Figure 7 suggests that the older and less familiar the literature, the more time the instructor spends lecturing. While a course’s chronological period may play a part in the proportion of time devoted to teacher talk in relation to student talk, these findings indicate that among the study participants, lecture takes up decidedly more class time than discussion. On average, the participants spent 63 percent of the time in their literature classes listening to lecture and 37 percent of class time discussing. By comparison, in 1990, teachers “spent most of their class time in lecture and discussion, with each typically taking up about half the available time” (Huber, 1992, p. 50). According to the current small-scale study, instructors of English majors at my public regional comprehensive university devote even more class time to lecturing than they did in earlier decades. To support the claim more broadly, I would need to provide evidence from observations of several classes, preferably at several universities.

Furthermore, Huber’s language suggests the MLA’s desire to preserve tradition. She reports, as the director of research, that the traditional educational goals for their courses for the great majority of her respondents revolve around “providing students with the historical and intellectual background needed to understand the primary texts they are assigned and helping them to appreciate the merits of these texts” (1992, p. 52). Her use of the words “providing” and “helping” further suggests a lecturing scenario with students as the recipients. Huber seems reassured to report that traditional practices “remain in place” (p. 50).

The results of the current study indicate that students learn more by trying to articulate their own ideas to their classmates and the instructor. Figures 2, 3, and 4 show that discussion more than lecture links with learning at multiple points in the semester. Figure 5 shows that students prefer interacting in class rather than listening to the instructor lecture. Figure 6 shows that even with online tasks, students preferred interaction to solitary reflection.

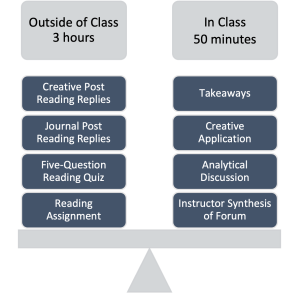

The participants’ responses suggest that most learning took place outside the classroom, while most of the engagement and practice occurred in the classroom. Outside the classroom, students spent about three hours preparing for a class; at their own pace, they accomplished the assigned tasks. Dialogic learning then continued in the classroom with the professor as well as classmates (Garrett & Nichols, 1991, p. 37). By replying to two journal and two creative posts and by reading replies to their own posts, according to Figure 8, students engaged in a minimum of four interactions with the group before meeting in class. Over the course of the semester, the class members developed relationships based on these online asynchronous interactions. Sometimes, the dialogic learning stemmed from discovering a likeminded sensibility, sometimes because a student offered a novel perspective on the reading. Figure 8 may not adequately convey the extent of the inverted learning because the number of tasks outside of class and in class is equal. However, the greater investment of time for the homework points to the flipped learning that rendered class dialogue meaningful.

In answer to the survey question, “What activity in the unit has helped the most to make you more articulate?” many participants singled out the importance of work outside of class.

- Commenting on classmates’ posts helped me understand my own (and their) opinions better.

- Sitting down and thinking about my response helped me with organizing my ideas.

- Blackboard has helped me the most. Everyone can have the opportunity to post their own ideas and thoughts, and the rest of the class can learn from their information. (Survey 3)

By the time we met for the fifty-minute class period, students had invested the greater amount of time in their learning. My role was to open the in-class discussion by identifying the strands of their pre-class discussion, supplementing gaps or clearing up misconceptions in their understanding, and engaging with their questions, both posted and spontaneous. Student discussion followed my mini-lecture. Sometimes we began class discussion in groups. For example, to recognize Yeats’ modernist tone, groups compared aspects of “When You Are Old” to the Ronsard sonnet on which it is based. The third segment of the class was devoted to students’ creative applications of the reading assignment. For another example, to characterize Victorian authors, following our performance of Act III of The Importance of Being Earnest, students prepared and presented two-minute role plays reviewing the performance from the perspective of Austen, Tennyson, Browning, Lear, Carroll, Gilbert, Kipling, and Wilde. Finally, in the last minutes of each class, we articulated our takeaways from the day’s interactions.

Conclusions

The current study provides a snapshot that may offer some insights and possibilities for English literature teaching while also acknowledging the limitations of the sample size. Allbaugh suggested there is an “already widely held preference for facilitating class discussion over lecturing” in the literature classroom (2004, p. 474). With the arrival of Gen Z to higher education and COVID-era challenges, researchers have accelerated their adjustments to student learning preferences. A literature review examining research from 2015 to 2021 on the trends of active learning in higher education underscores engagement’s contribution to students’ well-being (Ribeiro-Silva, 2022). Building on the recommendations made by Mohr and Mohr (2017) and Seemiller and Grace (2016), several guidelines emerge from the current study for tailoring teaching styles to the needs of post-COVID Generation Z students. The current study’s conclusions, despite its limited sample size (n=20), correspond with the findings of a recent study of university students’ learning preferences also conducted at a regional comprehensive university (Sytnik & Stopochkin, 2023). The study’s larger sample size (n=137) found that professors across several majors ranked lecture first out of fifteen selected teaching methods, whereas students ranked lecture fourteenth in effectiveness out of fifteen selected teaching methods (pp. 6-7). Concurring with other recent research, the current study found the following pressing teaching and learning preferences for today’s upper-level English majors.

Keep Communication Brief

Accommodate Generation Z students’ short attention span (Gilbert, B. G. et al., 2022; Huss, 2023; Seemiller & Grace, 2017). Gen Z students, because of technology, tend to have a shorter attention span than millennials. On computers and phones, attention spans are short and declining (Mark, 2023). While online learning allows for self-pacing and flexible attendance, in-class discussion and application of the content require a teacher to step off the soapbox and provide students immediate feedback, including answers to their questions. Gen Z learners prefer blended learning that is not monotonous (Helaluddin et al., 2023). Asked whether they practiced their discussion skills in all their classes, two Gen Z students described a particular discussion experience:

Student 1: I have the feeling it was more of a teacher-oriented discussion since the beginning, I felt like I’m always trying to contribute something, like my own idea, and then once I’ve contributed to the idea the professor is more like, “Eh, not really, this is kinda what it is . . . .” It wasn’t something that they thought fit with their view.

Student 2: Yeah, I’m in the same class as him and I’ve personally been shut down in class before trying to talk. So, I don’t speak in that class very often. (Bedetti, 2017)

Thus, instead of extended instructor soliloquies, democratizing the classroom entails “a demanding pedagogy that requires both preparation and openness to informed student readings” (Ashley, 2007, p. 208). Likewise, the rapid exchange of ideas in discussion requires students to encode their classmates’ ideas into their own contexts, as they build their arguments with the help of textual references, ideal skills to develop in a participatory democracy (Radaelli, 2015).

Students prefer short but relevant writing tasks, such as the succinct assignments outlined in Schillace’s (2012) course, Romancing the Marketplace: Why Degrees in English and the Liberal Arts Matter in the Today’s Economic Climate. Dealing with real-life issues that students are interested in, she argues, helps students build a bridge between major and career more than lengthy term papers or long-winded lectures. Instead, as Emre (2023) argues, instructors might allow discussion to overflow into the activities of daily life, “a wide world that stretches beyond the institutions of the Anglosphere” (para. 31). One instructor teaches multimedia memoir to help students integrate their voices into new writing spaces (Hillin, 2012). Other faculty have blended TikTok into courses for the English major (Revesencio et al., 2022). An example of a brief assignment from my course asked students reading Naipaul’s “One Out of Many” to compose a paragraph in response to the following prompt: “Picture what you want to become in America, your vision for your future, your ambition, the struggles you anticipate, and hurdles you expect to encounter to achieve your dream.” To maximize learning in each class period, Generation Z students challenge us to plan and sequence short segments into a coherent arc, with one brief activity flowing seamlessly into the next.

Co-Create

Allow Generation Z students to connect with learners of shared interests and move beyond the one-way depositing of knowledge and the routine of individual work. Our students are not in tune with or have the patience for traditional, passive instructional sources; they prefer to collaborate with each other and with faculty. An approach that empowered the students to recognize themselves as co-creators of knowledge within a classroom asked students to imagine what Dickens would have done to curate his Instagram feed (Huggins & Henderson, 2023). As recent research has shown, flipping the classroom provides the kind of engagement Generation Z students crave (Aydin & Demirer, 2022). In the words of the founder of the literature workshop, instructors have to “find ways to switch roles with [students]” (Blau, 2003, p. 2). Researchers have argued that the learning process is collective rather than isolated (Klages, 2004, p. 45; Linkin, 2010, p. 168; Murillo‑Zamorano et al., 2021). In a student-centered classroom, the emphasis is on conversation. American Gen Z emerging adult students have voiced the importance of relational connection and inclusion, with implications for team-based learning (Harrigan et al., 2021). An unsolicited student comment I received regarding a lower-division introductory literature survey acknowledges the power of student-centered co-creation: “I loved every play we read in class and have really found a deep appreciation and excitement for literature. I hope that one day many English classes will switch to this style of teaching (creativity) and keep students excited for learning!” (Gartland, 2017). Klages reported similar feedback about open discussion from her students in a sophomore-level literature class (2004, p. 170). The integrative English major includes the kind of student-faculty collaboration that has been longstanding outside of the humanities: “As the trend toward involving undergraduates in research suggests, it is important to engage students with faculty scholarly interests and the issues and arguments debated in the discipline” (MLA Teagle Foundation Working Group, 2009, p. 7). Increasingly, deploying undergraduate research is part of the redefinition of how we think about English undergraduate studies (Ballentine, 2022). Students learn by doing, not only by paying attention.

Interact In-Person

What emerged from the pandemic most clearly for instructors is the need to recognize students as whole people (Carillo, 2023). Upon returning to campus, students’ lack of ease with each other was profound, understandably since a traditional first-year student will have spent a fifth of their adolescence deprived of in-person interaction with friends. One English major’s chronicle of his academic year during the pandemic is marked by a sense of loneliness (Farney, 2023). The resulting lack of academic socialization when students returned to the classroom heightens the need to practice in-person interaction. At the end of a relationship-rich course, my students are fully aware of how each classmate has contributed to their learning experience (Student compliments, 2017). A resilient pedagogy includes acknowledging the trauma that many of our students have endured throughout their lives (Greensmith et al., 2023; Munro, 2022). It includes rewarding the cultural wealth and cultural capital of minoritized students (Maghsoodi et al., 2023). For example, in my Enjoying Lit class one day halfway through the semester, an African American student from Atlanta observed that she and a Hispanic student were the only non-Caucasians in the room. We had created a social space where she felt a “contact zone” (Zito, 2023) in which she could share feelings about her sense of social fit and belongingness in our central Kentucky classroom. Encouraging students to speak up nurtures agency and develops emotional as well as intellectual intelligence.

Often less skilled at interpersonal face-to-face interactions and networking than millennials, Generation Z students seek relevant professional and communication experience rather than lectures and independent, isolated work (Cook, 2015). For example, an instructor divided twenty members of a Survey of American Literature II class into six teams, each of which “collabo-wrote” a publishable scholarly article (Blythe and Sweet, 2008, p. 323). Even with audiovisual presentations, a course feature reported as used by almost 40 percent of the 1990 MLA Survey respondents (Huber, 1992, p. 51), faculty can make interactive strategies recognizable and thus “create confidence in students that interactive skills are learnable” (Godó, 2012, p. 76). Discussion fulfills students’ need to articulate their viewpoints to others, to recognize and contextualize others’ viewpoints, and to hear their own viewpoints restated. By giving students the ability to restate and reorganize information in relation to their own experiences, they develop their Elaborative Processing skills (Bedetti, 2017). A peer observer of my literature class concluded his assessment by remarking, “I’ve never observed a class in all my career that had a hundred percent fully engaged participation” (Rahimzadeh, 2022). According to Redaelli, “developing such interpersonal skills is pivotal for academic performance and career success” (2015, p. 346). “Rather than abandoning students to a crowded solitude,” Redaelli (2015, p. 350) argues that we educate for participation in a democratic life. Thus, the major is the place where students gain the riches that will be their intellectual capital for the rest of their lives. Using video games-as-literature can help nurture students’ motivations to persist in the English major and help them construct their disciplinary identity (Nicholes, 2020). Including career mapping in the English major helps with recruitment and retention (Rafes et al., 2014). Not surprisingly, after COVID, students in an innovative classroom have expressed more satisfaction with an environment where they are more likely to be talking to their peers, sensed more community, and perceived these classrooms as more appropriate to their learning (Britt et al., 2022). Many instructors are rushing to meet today’s students on their own terms.

Further research of English major learning and teaching styles is needed to provide evidence from observations of several classes, preferably at several universities and by an outside observer, such as a graduate or Work-Study student. Identifying the learning preferences of Gen Z literature students also requires surveys of several classes at comparable regional comprehensive universities. As Børte et al. (2023) have done across disciplines, it would be useful to survey not only for English majors’ perception of their learning styles but also to survey their instructors for their perception of their teaching styles. One or more impartial observers could measure the minutes devoted to each teaching style. Such a large-scale study could provide three percentages—student perception, teacher perception, and objective measurement—and result in more persuasive data about how well teaching and learning styles match. Ideally, the investigator would not also be an instructor of record.

As new skills and technologies take over, English Departments “also need to up-skill and re-skill themselves” (Whitehead, 2023, p. 32). From semester to semester, English instructors seek to disprove Børte et al.’s (2023) finding that “despite frequent calls for more student-active learning, studies find that teaching remains predominantly traditional and teacher-centered” and seek “better alignment between research and teaching practices” (p. 597). The most striking finding in Børte et al.’s review of the literature was “the discrepancy between how academics work when they conduct research and when they teach” (p. 610). Instructors can bridge that gap by translating theory into practice in their course format and in each lesson plan. My daily planning time occurs on the drive home as I reflect on the recent class meeting. Like many other instructors, I consider the level of students’ engagement with the reading assignment, the rhythm of the class period (Bedetti, 2012), and where we are in the semester (Bedetti, 2013). If my Gen Z students seemed less engaged than usual, I feel challenged to create novel segments for the next meeting. When the tasks build into a coherent whole, students and instructor leave the literature classroom tangibly elated. At the final meeting of my course, the round robin of compliments that each student gives every classmate reveals how keenly responsive they have been to each other’s talents and sensibilities. As their instructors are building their English Department back better, students are experiencing how their confidence, communication, and interpersonal skills render them more agile and collaborative in the new workplace.

References

ADE Ad hoc Committee on the English Major. (2018, July). A changing major: The report of the 2016–17 ADE ad hoc committee on the English major.” Association of Departments of English. https://www.maps.mla.org/content/download/98513/file/A%20-Changing-Major.pdf

Allbaugh, T. (2004). Active learning: Some questions for literary studies. Pedagogy, 4(3), 469-474. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/173745

American Academy of Arts and Sciences. (2019). Gender distribution of degrees in English language and literature. Humanities Indicators. www.humanitiesindicators.org/content/indicatordoc.aspx?i=243

American Academy of Arts and Sciences. (2021). Bachelor’s degrees in the humanities. Humanities Indicators, www.humanitiesindicators.org/content/indicatordoc.aspx?i=34

Ashley, H. M. (2007). Multicultural hybridity: Transforming American literary scholarship and pedagogy. College Literature, 34(4), 207-209. https://muse.jhu.edu/pub/33/article/222388/pdf

Aydin, B., & Demirer, V. (2022). Are flipped classrooms less stressful and more successful? An experimental study on college students. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 19(1), 1–17. https://doaj.org/article/6bbaa46fdb354f5c8c42b29ddbfbc4da

Ballentine, B. C. (2022). Undergraduate research and the enrollment crisis in English literature: four lessons from the sciences. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 22(1), 43-60. https://muse-jhu-edu.libproxy.eku.edu/article/842786

Bedetti, G. (2012). Class flow: Orchestrating a class period. Kentucky English Bulletin, 61(2), pp. 25-28. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/open?id=0B7vjxLe6c83nWl9xcVFlQUhrTjA

Bedetti, G. (2013). Avoiding the Mid-Semester Wall: Using a Real World Course Project. National Teaching & Learning Forum, 22(5), 6–7. https://research-ebsco-com.libproxy.eku.edu/c/d7lpk6/viewer/pdf/re7w6f47g5

Bedetti, G. (2017). Academic socialization: Mentoring new honors students in metadiscourse. Honors in Practice, 13, 109-140. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1259&context=nchchip

Blau, S. D. (2003). The literature workshop: Teaching texts and their readers. Heinemann.

Blythe, H., & Sweet, C. (2008). The writing community: A new model for the creative writing classroom. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 8(2), 305–325. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1215/15314200-2007-042

Børte, K., Nesje, K., & Lillejord, S. (2023). Barriers to student active learning in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 28(3), 597–615. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1080/13562517.2020.1839746

Bonwell, C. C., & Eison, J. A. (1991). Active Learning: Creating Excitement in the Classroom. 1991 ASHE-ERIC Higher Education Reports.

Britt, L. L., Ball, T. C., Whitfield, T. S., & Woo, C. W. (2022). Students’ perception of the classroom environment: A comparison between innovative and traditional classrooms. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 22(1). https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v22i1.30735

Buchanan, J. M. (2016). English education and the teaching of literature. CEA Forum, 45(1), 78–98. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1107061.pdf

Bureau of Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. (2023, January 24). Writers and authors. Occupational Outlook Handbook. Retrieved July 17, 2023, from https://www.bls.gov/ooh/media-and-communication/writers-and-authors.htm

Carillo, E. C. (2023). What I learned about teaching while teaching Mrs. Dalloway during the pandemic. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 23(1), 1–9. https://www.muse.jhu.edu/article/886877

Cook, V. S. (2015). Engaging Generation Z students. Center for Online Learning Research and Service, U of Illinois Springfield. https://sites.google.com/a/uis.edu/colrs_cook/home/engaging-generation-z-students

Corrigan, P. T. (2017). Teaching what we do in literary studies. Pedagogy, 17(3), 549–556. https://muse-jhu-edu.libproxy.eku.edu/article/671062

Emre, M. (2023). Everyone’s a critic. New Yorker, 98(46), 62–66. https://eds-p-ebscohost-com.libproxy.eku.edu/eds/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=ff0be01d-e995-48da-ac74-affd0d7d71b7%40redis&bdata=JkF1dGhUeXBlPWlwJnNpdGU9ZWRzLWxpdmUmc2NvcGU9c2l0ZQ%3d%3d#

Farney, O. (2023). Settling. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 23(1), 173–176. https://muse-jhu-edu.libproxy.eku.edu/article/886873

Garrett, M., & Nichols, A. (1991). “Look who’s talking”: Dialogic learning in the undergraduate classroom. ADE Bulletin, 99, 34–37.

Gartland, G. (2017). ENG 210W. Received by Gaby Bedetti, 14 Dec. 2017. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1GLsiD_thTqZOjQjnk7N0PPKOATEodath/view?usp=sharing

Gilbert, B. G., Mathis, D. P., Henry, B., Gibbs, A., & Lee, V. (2022). “The professor I like!” Generation Z students and their teachers. ABNFF Journal, 1(3), 22–28.

Gilbert, C. J. (2021). A comic road to interiors, or the pedagogical matter of Gen Z humor. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 21(4), 69–88. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.14434/josotl.v21i4.32749

Godó, Á. M. (2012). Are you with me? A metadiscursive analysis of interactive strategies in college students’ course presentations. International Journal of English Studies, 12(1), 55–78. https://revistas.um.es/ijes/article/download/ijes.12.1.118281/134191

Greensmith, C., Channer, B., Evans, S. Z., & McGrew, M. (2023). Reflections on undergraduate research and the value of resilient pedagogy in higher education. Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching & Learning, 23(1), 31–45. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.14434/josotl.v23i1.33163

Harrigan, M. M., Benz, I., Hauck, C., LaRocca, E., Renders, R., & Roney, S. (2021). The dialectical experience of the fear of missing out for U.S. American iGen emerging adult college students. Journal of Applied Communication Research, 49(4), 424–440. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1080/00909882.2021.1898656

Helaluddin, Fitriyyah, D., Rante, S. V. N., Tulak, H., Ulfah, S. M., & Wijaya, H. (2023). Gen Z students perception of ideal learning in post-pandemic: A phenomenological study from Indonesia. International Journal of Educational Methodology, 9(2), 423–434. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.12973/ijem.9.2.423

Heller, N. (2023). The end of the English major. New Yorker, 99(3), 28–39. https://libproxy.eku.edu/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip&db=asn&AN=162073529&site=eds-live&scope=site

Hewings, A., Prescott, L., & Seargeant, P. (2016). Futures for English Studies: Teaching Language, Literature and Creative Writing in Higher Education. Palgrave Macmillan.

Hillin, S. P. (2012). “Does this mean we’re cyborgs too?”: Teaching multimedia memoir to English majors. Writing and Pedagogy, 4(1), 99-119. https://journals.equinoxpub.com/index.php/WAP/article/view/8999/pdf

Hiner, A. (2012). The viability of the English major in the current economy. CEA Forum, 41(1), 20–52. http://files.eric.ed.gov.libproxy.eku.edu/fulltext/EJ991799.pdf

Houston, H. R., Keller, E. L., Kritzman, L. D., Madden, F., Mahoney, J. L., McGinnis, S., Monta, S. B., Perl, S., & Swaffar, J. (2001). Final report: MLA ad hoc committee on teaching. Profession, 225–238. https://www-jstor-org.libproxy.eku.edu/stable/25607199

Huber, B. J. (1992). Today’s literature classroom: Findings from the MLA’s 1990 survey of upper-division courses. ADE Bulletin, 101, 36–60. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1632/ade.101.36

Huber, B. J., & Laurence, D. (1989). Report on the 1984-85 survey of the English sample: General education requirements in English and the English major. ADE Bulletin, 93, 30–43. https://discovery-ebsco-com.libproxy.eku.edu/c/d7lpk6/viewer/pdf/omiawmc4yb

Huggins, S. P., & Henderson, K. (2023). What the Dickens: Student empowerment through collaboration in a single-author course. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 23(1), 192–200. https://discovery-ebsco-com.libproxy.eku.edu/linkprocessor/v2-external?opid=d7lpk6&recordId=4nejlgl565&url=https%3A%2F%2Fmuse.jhu.edu%2Farticle%2F886876

Huss, J. (2023). Gen Z students are filling our online classrooms: Do our teaching methods need a reboot? InSight, 18, 101–112. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.46504/18202306hu

Johnson, D. B., & Sveen, L. W. (2020). Three key values of Generation Z: Equitably serving the next generation of students. College & University: The Journal of the American Association of Collegiate Registrars, 95(1), 37–40. https://discovery-ebsco-com.libproxy.eku.edu/c/d7lpk6/viewer/pdf/omiawmc4yb

Kalata, K. (2016). Prioritizing student skill development in the small college literature survey. CEA Forum, 45(2), 54–85. https://eric-ed-gov.libproxy.eku.edu/?id=EJ1132554

Klages, M. (2004). The dark night of the subject position, or, the pedagogical paradoxes of poststructuralism. Education & Society, 22(2), 45–55.

Laurence, D. (2017, June 26). The decline in humanities majors. The Trend: The Blog of the MLA Office of Research. https://www.stylemlaresearch.mla.hcommons.org/2017/06/26/the-decline-in-humanities-majors/

Lang, J. M., Dujardin, G., & Staunton, J. A. (2018). Teaching the Literature Survey Course : New Strategies for College Faculty. West Virginia University Press.

Letters. (2023, January 15). Is poetry dead? Listen to the poets. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2023/01/15/opinion/letters/is-poetry-dead.html

Linkin, H. K. (2010). Performing discussion: The dream of a common language in the literature classroom. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 10(1), 167–174. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1215/15314200-2009-029

Maghsoodi, A. H., Ruedas-Gracia, N., & Jiang, G. (2023). Measuring college belongingness: structure and measurement of the sense of social fit scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 70(4), 424–435. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1037/cou0000668.

The Mail. (2023, March 2023). Letters respond to Nathan Heller’s piece about the decline of the English major. The New Yorker (Online). https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2023/03/27/letters-from-the-march-27-2023-issue

Mark, G. (2023, Jan 06). How to Restore Our Dwindling Attention Spans; Digital distractions are ramping up our natural tendency to shift focus, raising stress levels and hurting productivity. But we can still take control. Wall Street Journal (Online). https://libproxy.eku.edu/login?url=https://www.proquest.com/newspapers/how-restore-our-dwindling-attention-spans-digital/docview/2761263154/se-2

Marx, J., & Garrett Cooper, M. (2020). Curricular innovation and the degree-program explosion. Profession, 2. https://profession-mla-org.libproxy.eku.edu/curricular-innovation-and-the-degree-program-explosion/

Miller, T. P. (2011). The Evolution of College English : Literacy Studies from the Puritans to the Postmoderns. University of Pittsburgh Press.

MLA Teagle Foundation Working Group. (2009). Report to the Teagle Foundation on the undergraduate major in language and literature. Profession, 285–312. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1632/prof.2009.2009.1.285

Mohr, K. A., & Mohr, E. S. (2017). Understanding Generation Z students to promote a contemporary learning environment. Journal on Empowering Teaching Excellence, 1(1), 9. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1005&context=jete

Munro, B. (2022). Human and professor: Using trauma-informed pedagogy to reimagine teaching in the wake of COVID-19. CEA Critic: An Official Journal of the College English Association, 84(2), 130–146. https://muse-jhu-edu.libproxy.eku.edu/article/866357

Murillo-Zamorano, L. R., López Sánchez, J. A., Godoy-Caballero, A. L. & Bueno Muñoz, C. (2021). Gamification and active learning in higher education: is it possible to match digital society, academia and students’ interests? International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 18(1), 1–27. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1186/s41239-021-00249-y

Napier, T., Cole, A. J., & Banks, L. C. (2018). The evolution of Eastern Kentucky University libraries orientations: Giving students a LIbStart to student success through library engagement. In Planning Academic Library Orientations: Case Studies from Around the World (pp. 273-281). Elsevier.

Nicholes, J. (2020). Engaging English majors with video games: Implications for English major identity formation. Journal of Teaching Writing, 35(1), 1-24. https://journals.iupui.edu/index.php/teachingwriting/article/download/26155/24216.

Ortmann, L., Stutelberg, E., Allen, K., Beach, R., Kleese, N., Peterson, D., Yoon, S. R., Schick, A., Gambino, A., Share, J., Brodeur, K., Crampton, A., Faase, C., Israelson, M., Madison, S. M., Ian O, B. W., Cole, M., Doerr-Stevens, C., Frederick, A., & Jocius, R. (2023). Annotated Bibliography of Research in the Teaching of English. Research in the Teaching of English, 57(3), AB1-AB46.

Parry, M. (2016, 27 November). What’s wrong with literary studies? Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/whats-wrong-with-literary-studies/

Phillips, K. F., & Sontheimer, H. (2023). Neuroscience: The new English major? The Neuroscientist, 29(2), 158–165. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1177/10738584211003992

Redaelli, E. (2015). Educating for participation: Democratic life and performative learning. Journal of General Education, 64(4), 334–353. https://www-jstor-org.libproxy.eku.edu/stable/10.5325/jgeneeduc.64.4.0334

Rafes, R. S., Malta, S. L., & Siniscarco, M. T. (2014). Career mapping: An innovation in college recruitment and retention. college & university, 90(1), 47–52. https://discovery-ebsco-com.libproxy.eku.edu/c/d7lpk6/viewer/pdf/3jhionbyhj

Rahimzadeh, Kevin. (2022). Classroom/online observation of teaching effectiveness. Received by Gaby Bedetti, 1 Mar. 2022. Retrieved from https://docs.google.com/document/d/1F8P9BhMAj7PxKYaKBoMoqQeT__ZFFNph/edit.

Read, D. (2019). Booms, busts, and the English major. ADE Bulletin, 157, 15–22. https://www.maps.mla.org/Bulletins/ADE-Bulletin

Revesencio, N. I., Alonsagay, R. R., Dominguez, L. I., Hormillosa, D. M. I., Ibea, C. H. I., Montaño, M. M. S., & Biray, E. T. (2022). TikTok and grammar skills in English: Perspectives of English major students. International Journal of Multidisciplinary: Applied Business & Education Research, 3(11), 2226–2233. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.11594/ijmaber.03.11.09

Ribeiro-Silva, E., Amorim, C., Aparicio-Herguedas, J. L., & Batista, P. (2022). Trends of active learning in higher education and students’ well-being: A literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.844236

Richardson, T. R., & Kring, J. P. (1997). Student characteristics and learning or grade orientation influence preferred teaching style. College Student Journal, 31(3), 347. https://discovery-ebsco-com.libproxy.eku.edu/c/d7lpk6/viewer/html/hnso3235qr

Schillace, B. (2012). Jumping the connection gap: helping students build a bridge between major and career. CEA Forum, 41(1), 1–19. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ991798.pdf

Schramm, M., Mitchell, J. L., Stephens, D., & Lawrence, D. (2003). The undergraduate English major. ADE Bulletin, 134, https://www.mla.org/content/download/26434/file/adhoc_major.pdf

Scott, A. O. (2023, June 25). The reading crisis: Book bans, chatbots, pedagogical warfare. Does literacy have a future? The New York Times Book Review, 1, 14-16.

Seemiller, C., & Grace, M. (2016). Generation Z Goes to College. John Wiley & Sons. http://apps.nacada.ksu.edu/conferences/ProposalsPHP/uploads/handouts/2021/C177-H05.pdf

Student compliments to her classmates. Retrieved from https://drive.google.com/file/d/1rzBzRN98XwKPERVLnih_9fm72UviVh10/view?usp=sharing

Swofford, S., & Kilgore, R. (2020). We need to talk: Making writing and literature work for the future. ADE Bulletin, 158, 45–58. https://www.maps.mla.org/Bulletins/ADE-Bulletin

Sytnik, I., & Stopochkin, A. (2023). A model for the selection of active learning while taking into account modern student behavior styles. Education Sciences, 13(7), 693. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.3390/educsci13070693

Trivedi, A. (2023). Preparing for the posthistorical university: Teaching capital in the creative writing classroom. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 23(1), 91–111. https://muse-jhu-edu.libproxy.eku.edu/article/886883

Walther, M. (2022, December 29). Poetry died 100 years ago this month. The New York Times (Online). https://www.nytimes.com/2022/12/29/opinion/eliot-waste-land-poetry.html

Walther, M. (2023, July 23). The death of poetry: A second inquest. The Lamp: A Catholic Journal of Literature, Science, The Fine Arts, Etc., 18. https://thelampmagazine.com/blog/the-death-of-poetry-a-second-inquest

Whitehead, E. (2023). Augmented skills of educators teaching Generation Z. Excellence in Education Journal, 12(1), 32–54.

Zhao, Y. (2022). Build back better: Avoid the learning loss trap. Prospects (00331538), 51(4), 557–561. https://doi-org.libproxy.eku.edu/10.1007/s11125-021-09544-y

Zito, A. J. (2023). “I could never say that out loud”: Holding out in introductory literature courses. Pedagogy: Critical Approaches to Teaching Literature, Language, Composition, and Culture, 23(1), 147–171. https://muse-jhu-edu.libproxy.eku.edu/article/886872

Appendix: Survey of Learning Styles in Today’s Upper-Division English Major

Questionnaire

- to become familiar with the major writers and their works

- to understand how the writers fall into canonical literary periods

- to think, speak, and write effectively about the literature

Please rank the course activities on a scale of 1 (not much) to 5 (much).

| Activity | How much did you enjoy doing the activity? | How much did the activity help you learn |

|---|---|---|

|

1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

|

1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

|

1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

|

1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

|

1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

|

1 2 3 4 5 | 1 2 3 4 5 |

Please answer the following questions about your learning.

- Did you have a study partner/group?

- Yes

- No

- Which activities contributed more to your learning?

- Solitary

- Interactive

- In what ways have you become more articulate discussing the literature orally or in writing?

- What activity in the unit has helped the most to make you more articulate?

- Do you have comments, observations, and/or suggestions for enhancing your learning?

Please answer a question about your upper-level literature courses.

- What percent of class time is devoted to lecture and discussion in each course?